When we think of iconic artist couples, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera undoubtedly come to mind. Their relationship, marked by intense passion, profound love, and deep-seated turmoil, is as legendary as their individual contributions to the world of art. Spanning decades, their union was a whirlwind of emotional highs and lows, reflected in their works that continue to captivate audiences worldwide. This article delves into the intricacies of their tumultuous but passionate relationship, shedding light on how their personal and professional lives intertwined to create a lasting legacy.

Frida Kahlo was born on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico City, in a house known as La Casa Azul (The Blue House). Her early life was marked by tragedy, including a bout with polio at the age of six, which left her with a limp. However, it was a horrific bus accident at the age of 18 that truly shaped her future. The accident caused severe injuries, including a broken spinal column and a shattered pelvis, which led to numerous surgeries and chronic pain throughout her life. During her long recovery, Kahlo began to paint, using art as a means to cope with her physical and emotional suffering.

Diego Rivera, born on December 8, 1886, in Guanajuato, Mexico, was already an established artist by the time he met Kahlo. Rivera was known for his large-scale murals that depicted Mexican society and were imbued with strong political messages. A prominent figure in the Mexican muralism movement, Rivera’s work was heavily influenced by his belief in social justice and the plight of the working class. His murals can be seen in prominent locations across Mexico and the United States.

The first encounter between Kahlo and Rivera occurred when she was a student. Intrigued by Rivera’s work, Kahlo sought his opinion on her own paintings. Their meeting in 1928 was the beginning of a complex and enduring relationship. Rivera was immediately impressed by Kahlo’s talent and encouraged her to pursue her artistic career. Despite a significant age difference – Rivera was 42 and Kahlo 21 – they found common ground in their shared passion for art and politics.

Marriage and Early Years Together

Kahlo and Rivera married on August 21, 1929. Their union was far from conventional; both artists had strong personalities and lived their lives with intense fervor. Their marriage was characterized by mutual admiration for each other’s work, but also by infidelity, jealousy, and fierce arguments. Rivera’s numerous affairs, including one with Kahlo’s younger sister, Cristina, were a constant source of pain for Kahlo. Despite this, their bond remained unbroken, driven by their deep emotional and intellectual connection.

Kahlo and Rivera’s relationship was not only a personal journey but also a professional collaboration. Rivera’s influence on Kahlo’s work was significant. He encouraged her to embrace her Mexican heritage, which became a central theme in her art. Kahlo’s paintings often included elements of Mexican folk art, combining vibrant colors and dramatic symbolism to explore themes of identity, pain, and love. Rivera, in turn, drew inspiration from Kahlo’s unique perspective and emotional intensity.

Their early years together were also marked by political activism. Both artists were staunch communists, and their political beliefs were reflected in their art. They were actively involved in the Mexican Communist Party and hosted numerous political gatherings at their home. This shared commitment to social justice further strengthened their bond, as they both believed in using their art to bring about societal change.

Rivera’s impact on Kahlo’s art cannot be overstated. When they met, Kahlo was still developing her unique style. Rivera recognized her talent and pushed her to pursue her artistic vision, free from external influences. He encouraged her to draw inspiration from her own experiences, particularly her physical pain and cultural identity.

Under Rivera’s guidance, Kahlo began to explore themes that would become central to her work. Her paintings often depicted her own suffering, but they were also imbued with elements of Mexican culture and symbolism. For instance, in her famous painting “The Two Fridas” (1939), Kahlo explores her dual heritage – one Frida in traditional Tehuana dress, representing her Mexican roots, and the other in a European-style white dress, symbolizing her more modern, cosmopolitan identity. This exploration of identity was a recurring theme in Kahlo’s work, influenced by Rivera’s emphasis on Mexican cultural pride.

Kahlo’s use of vibrant colors and dramatic contrasts can also be attributed to Rivera’s influence. He encouraged her to use bright, bold colors typical of Mexican folk art, which became a hallmark of her style. Paintings such as “Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird” (1940) showcase her mastery of color and her ability to convey deep emotion through vivid imagery.

While Rivera had a profound influence on Kahlo’s work, the impact was mutual. Kahlo’s presence in Rivera’s life brought a new dimension to his art. Her emotional depth and personal struggle resonated with him, inspiring him to explore more intimate and personal themes in his murals.

Rivera’s work often focused on grand, sweeping themes of Mexican history and social justice. However, Kahlo’s influence encouraged him to incorporate more personal elements into his murals. Her ability to convey profound emotion through her art made Rivera more attuned to the emotional undercurrents in his own work.

One notable example of Kahlo’s influence on Rivera is his mural “Pan American Unity” (1940), created for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. The mural depicts the unity of North and South America, but it also includes more personal and intimate scenes, reflecting Rivera’s evolving approach to art. Kahlo’s influence helped Rivera blend the grand themes of social justice with the personal, creating a more nuanced and emotionally resonant body of work.

The Turbulence in Their Relationship

Despite their deep love and mutual respect, Kahlo and Rivera’s relationship was fraught with turbulence. Rivera’s numerous affairs were a significant source of tension, causing Kahlo immense emotional pain. Her own extramarital relationships, including with notable figures such as Leon Trotsky and Josephine Baker, added to the complexity of their marriage.

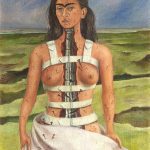

Kahlo’s health problems further strained their relationship. The physical pain from her bus accident never fully subsided, leading to numerous surgeries and long periods of bedridden recovery. Rivera’s dedication to his work often left Kahlo feeling isolated and neglected during these times. Her painting “The Broken Column” (1944), depicting her body split open with a crumbling column replacing her spine, poignantly illustrates her physical and emotional suffering.

Despite these challenges, their bond remained unbroken. They divorced in 1939 but remarried a year later, unable to stay apart for long. Their second marriage, though still tumultuous, was marked by a deeper understanding and acceptance of each other’s flaws and imperfections.

Kahlo and Rivera’s collaboration extended beyond their personal relationship. They often worked together on artistic projects, sharing ideas and techniques. Their home, La Casa Azul, became a hub of artistic and intellectual exchange, attracting artists, writers, and political figures from around the world.

One of their most notable collaborations was on the murals Rivera painted in the United States. Kahlo accompanied him on these trips, providing emotional and artistic support. Rivera’s murals in Detroit, San Francisco, and New York City reflect the influence of their shared experiences and political beliefs.

In Detroit, Rivera’s “Detroit Industry Murals” (1932-33) depicted the working class and industrial progress, themes close to both artists’ hearts. Kahlo’s presence during this period influenced Rivera’s portrayal of the human element within the industrial landscape. Her own work during this time, such as “Henry Ford Hospital” (1932), reflected her personal struggles and the couple’s shared commitment to social justice.

Kahlo and Rivera were deeply committed to their political beliefs, which played a significant role in their relationship. Both were active members of the Mexican Communist Party and used their art to express their political views. They believed in the power of art to bring about social change and were vocal advocates for workers’ rights and social justice.

Their political engagement often brought them into conflict with authorities. Rivera’s murals were sometimes controversial, leading to clashes with patrons and the government. His mural “Man at the Crossroads” (1933), commissioned for the Rockefeller Center in New York, was famously destroyed because it included a portrait of Lenin, reflecting Rivera’s communist beliefs.

Kahlo’s political activism was equally fervent. Her art often depicted revolutionary themes and figures, such as in her painting “Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick” (1954). Her involvement with the Mexican Communist Party brought her into contact with other prominent communists, including Leon Trotsky, who briefly lived with Kahlo and Rivera in Mexico.

Despite their shared political beliefs, Kahlo and Rivera sometimes clashed ideologically. Rivera’s unwavering commitment to communism sometimes conflicted with Kahlo’s more nuanced and personal approach to politics. However, their shared dedication to social justice and their belief in the transformative power of art kept them united in their political pursuits.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In the later years of their lives, Kahlo and Rivera’s relationship evolved into a deep, enduring companionship. Despite the many challenges they faced, their bond remained strong. Kahlo’s health continued to decline, and she spent her final years in great pain. Rivera remained devoted to her, providing care and support.

Frida Kahlo passed away on July 13, 1954, at the age of 47. Her death left Rivera devastated, and he continued to honor her memory through his work. Rivera’s later murals, such as those in the National Palace in Mexico City, reflect the influence of Kahlo’s life and art. He passed away three years later, on November 24, 1957.

The legacy of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera lives on in their art, which continues to inspire and captivate audiences around the world. Their relationship, marked by intense passion, deep love, and profound turmoil, is a testament to the power of art and the complexities of human connection.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s relationship was one of the most dynamic and influential in the history of art. Their intense passion for each other, combined with their shared commitment to art and social justice, created a partnership that profoundly impacted their work and the world around them.

Their tumultuous but passionate relationship, characterized by mutual admiration, infidelity, and profound emotional connection, is reflected in their art. Kahlo’s deeply personal paintings and Rivera’s grand, politically charged murals offer a window into their lives and the complex dynamics of their union.

Today, the legacy of Kahlo and Rivera continues to inspire artists, activists, and art lovers worldwide. Their story is a reminder of the power of love, passion, and creativity to transcend personal and political challenges, leaving an indelible mark on history.