Academic painting refers to a tradition of European art shaped by formal rules, institutional authority, and long-established ideals of beauty. It developed most clearly between the 17th and 19th centuries, with roots in Renaissance theories of proportion and harmony. By the 1600s, academies began codifying what constituted “serious” art, placing history, religion, and classical mythology above all other subjects. This system valued discipline, order, and continuity with the past rather than novelty for its own sake.

The most influential of these institutions was the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, founded in Paris in 1648 under King Louis XIV. Similar academies soon followed in Rome, Madrid, Vienna, and London, each reinforcing a shared artistic language. Students were trained to see painting as an intellectual and moral pursuit, not merely decorative craft. Painting was expected to elevate the viewer through noble themes and carefully reasoned composition.

Definition, origins, and academic foundations

At the core of academic painting were principles that could be taught, tested, and judged. Drawing from antique sculpture, studying anatomy, mastering linear perspective, and composing multi-figure scenes were considered essential skills. These standards were not arbitrary, but descended from classical philosophy and Renaissance theory developed between 1400 and 1550 AD. Academic painters believed that beauty was objective and could be approached through study and discipline.

Because academic painting was tied to institutions, it is often misunderstood as rigid or lifeless. In reality, it was a living tradition that evolved gradually over centuries. Its purpose was not rebellion, but refinement, preserving hard-won knowledge and passing it forward. Understanding this foundation is essential to understanding why academic painters were later dismissed.

The Academic Training System and Its Rigor

Becoming an academic painter required years of demanding education, often beginning in adolescence. Students typically entered preparatory schools before advancing to elite academies in their late teens or early twenties. Training emphasized patience, repetition, and humility before the masters of the past. Many artists spent a decade or more before achieving professional recognition.

Instruction followed a strict progression, beginning with drawing from engravings, then plaster casts, and finally live nude models. This method trained the eye to understand form, weight, and proportion with precision. Painting in color was delayed until drawing skills were proven sound. The goal was control, not self-expression in the modern sense.

Education, competitions, and professional pathways

Major competitions structured academic careers, most famously the Prix de Rome, established in 1663. Winners received state-funded study in Rome for several years, where they copied ancient sculpture and Renaissance frescoes. Artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, born in 1824 and graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts in the 1840s, followed this path. Salon exhibitions, held annually or biannually, served as the primary gateway to commissions, fame, and financial security.

Recognition came through medals, state purchases, and teaching appointments rather than shock value. Many academic painters married into stable middle-class families and lived long, productive lives devoted to their craft. Their careers were built slowly, based on trust earned through skill and reliability. This system produced consistency, but it also made academic painters vulnerable when tastes shifted abruptly.

Famous Academic Painters Who Fell from Favor

During the 19th century, academic painters were among the most celebrated artists in Europe and North America. Their works filled museums, government buildings, and private collections. Names like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, born in 1825 in La Rochelle, were synonymous with excellence. Bouguereau married Nelly Monchablon in 1866 and taught generations of students until his death in 1905.

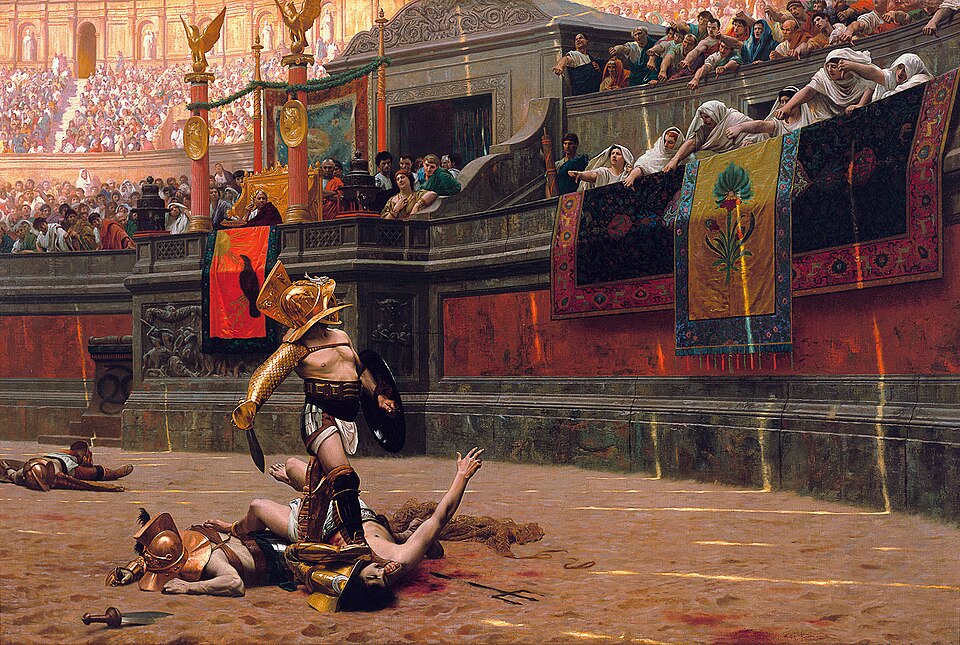

Alexandre Cabanel, born in 1823 and deceased in 1889, enjoyed similar prestige. His painting The Birth of Venus was purchased by Napoleon III in 1863, marking the height of official approval. Jean-Léon Gérôme, born in 1824 and died in 1904, balanced painting with sculpture and taught at the École des Beaux-Arts. These men were not fringe figures but cultural authorities.

Artists once celebrated and now sidelined

Their influence extended through direct teacher-student relationships that shaped European and American art schools. Gérôme taught Thomas Eakins, who later became a key figure in American realism. Bouguereau’s students included artists from Russia, Poland, and the United States, many of whom carried academic methods abroad. These networks formed a global artistic language grounded in shared standards.

Despite this dominance, their reputations collapsed rapidly after 1900. Museums relegated their works to storage, and textbooks reduced them to footnotes. Their fall from favor was not due to lack of skill or achievement, but to a change in values. Once the definition of progress shifted, academic painters were recast as obstacles rather than foundations.

The Rise of Modernism and Changing Artistic Values

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a dramatic redefinition of what art was supposed to accomplish. Movements such as Impressionism and Post-Impressionism rejected academic finish in favor of immediacy and personal vision. Brushwork became visible, subjects became ordinary, and rules were openly challenged. This shift was presented as liberation from tradition.

Critics increasingly equated innovation with moral and cultural advancement. Artists who broke rules were praised as courageous, while those who upheld standards were labeled conservative. The slow evolution valued by academic painters was reframed as stagnation. This new narrative favored rupture over continuity.

How new movements redefined “progress” in art

Modernist writers portrayed academic painters as out of touch with modern life. Technical mastery was dismissed as empty virtuosity, and historical subjects were seen as escapist. Museums and collectors followed critical trends, redirecting resources toward experimental work. By the mid-20th century, academic painters were largely absent from major exhibitions.

This shift was not neutral but ideological in nature. It elevated individual expression above shared cultural inheritance. In doing so, it narrowed the definition of artistic success. Academic painters, once central, became symbols of a past that modernism sought to overcome.

The Role of Art History Writing and Museum Curation

Art history as an academic discipline matured alongside modernism, shaping how the past was interpreted. Scholars emphasized linear narratives that led inevitably toward abstraction and conceptual art. Figures who did not fit this trajectory were minimized or excluded. Academic painters suffered most from this selective storytelling.

Museums reinforced these narratives through acquisition policies and gallery layouts. Wall space became a statement of values, and absence implied irrelevance. Visitors encountered modern art as the climax of history, with little context for what preceded it. Over time, omission hardened into assumption.

How narratives are shaped and reinforced

University curricula followed similar patterns, favoring movements aligned with modernist ideals. Students learned names like Manet and Cézanne but rarely studied Bouguereau or Cabanel in depth. Textbooks published after 1950 often mentioned academic painters only to criticize them. This repetition shaped generations of assumptions.

Once removed from teaching and display, academic painters faded from public memory. Their absence was not the result of new discoveries, but of repeated editorial choices. Art history, like any history, reflects the values of those who write it. Reconsidering academic painters requires questioning those inherited frameworks.

Misconceptions About Skill, Emotion, and Originality

One of the most persistent criticisms of academic painting is that it is emotionally cold. This claim misunderstands the difference between restraint and emptiness. Academic painters believed emotion should be guided by reason and narrative clarity. Their goal was lasting resonance, not immediate shock.

Another misconception is that technical skill suppresses originality. In truth, mastery provided freedom within structure. Painters could vary composition, gesture, and expression while remaining intelligible. Originality existed within tradition rather than against it.

Common criticisms and why they fall short

Academic painters often tackled profound themes such as sacrifice, faith, love, and mortality. These subjects required control to avoid melodrama or sentimentality. Their emotional power was subtle, unfolding through posture, light, and expression. This approach rewards patience rather than instant reaction.

Far from being mechanical, academic painting demanded moral seriousness. Artists saw themselves as custodians of cultural memory. Dismissing their work as soulless reflects modern impatience, not historical reality. A fair assessment requires judging them by their own aims, not ours.

Reassessment and the Return of Academic Appreciation

In recent decades, interest in academic painters has quietly revived. Auction prices for works by Bouguereau and Gérôme have risen steadily since the 1990s. Museums have mounted retrospective exhibitions that draw large audiences. Viewers often respond with surprise at the beauty and clarity of these works.

Contemporary realist painters increasingly study academic methods. Atelier-based training programs have reopened in Europe and North America. These artists value drawing, anatomy, and composition as foundations rather than constraints. The tradition, once dismissed, is being rebuilt.

Renewed interest among collectors, artists, and scholars

Scholars have begun reassessing academic painters without modernist bias. New research highlights their global influence and technical achievements. Rather than obstacles to progress, they are now seen as part of a broader continuum. This balanced view enriches art history rather than narrowing it.

Academic painters remind us that skill, discipline, and continuity matter. Their rediscovery is not a rejection of modern art, but a correction of imbalance. Honoring them restores depth and honesty to our understanding of the past. Tradition, when properly understood, is not the enemy of creativity but its backbone.

Key Takeaways

- Academic painters were central figures in European art from the 1600s through the late 1800s.

- Their rigorous training systems emphasized discipline, skill, and moral seriousness.

- Modernist narratives reframed innovation as rupture, sidelining academic traditions.

- Art history writing and museum practices reinforced these exclusions over time.

- Renewed interest shows that academic painting still speaks powerfully today.

FAQs

- What defines an academic painter?

- Why were academic painters dominant in the 19th century?

- How did modernism contribute to their decline?

- Are academic painters being reassessed today?

- Can academic methods still be relevant for modern artists?