The White Mountains of New Hampshire, with their sweeping ridgelines, pristine valleys, and clear mountain light, captured the imagination of 19th-century American artists like few places ever had. These highlands, forming part of the northern Appalachian range, became the epicenter of a homegrown movement in landscape painting that rivaled the great schools of Europe. As the Industrial Revolution surged ahead in the cities, artists and patrons alike yearned for untouched wilderness, for scenes that spoke of God’s hand in nature, not man’s machines. The result was a flourishing of artistic inspiration rooted deeply in the American soil.

By the early 1800s, these mountains had already become subjects of popular fascination. Writers, theologians, and early tourists extolled their grandeur in prose and poetry. However, it wasn’t until the 1830s and 1840s that artists began to journey north with palettes in hand, inspired by the earlier work of the Hudson River School and drawn by the lure of something raw and sublime. Paintings of the White Mountains quickly became a cultural counterbalance to growing urbanization and were seen as visual affirmations of divine order.

This movement, now known as White Mountain art, was born out of a particular historical and spiritual mindset. It emphasized moral clarity, natural beauty, and national pride. It also paralleled the expansion of railroads into the New England interior, making the region more accessible to tourists and artists alike. With the rise of travel culture, wealthy patrons sought keepsakes of their adventures, and landscape paintings became not only sentimental treasures but status symbols.

The expanding infrastructure helped solidify the movement’s presence. By 1851, the completion of the Portland and Ogdensburg Railroad into the region brought visitors directly to the heart of the mountains. Hotels, like the Crawford House and the Glen House, catered to travelers who desired both comfort and wilderness. Many artists would exhibit their works in these lodges, offering paintings for sale or commission. Thus, the White Mountains became both muse and marketplace, setting the stage for a rich artistic tradition.

Pioneering Artists of the White Mountains

While the roots of White Mountain art were forming in the early 19th century, it was Thomas Cole’s 1839 visit to the region that would serve as an unofficial genesis for the artistic movement. Cole, considered the father of the Hudson River School, found in the White Mountains a sublime beauty that exceeded his expectations. His sketches of Mount Washington and the dramatic notches carved by glaciers would influence generations of landscape painters. Though he never became a permanent fixture in the region, his brief sojourn validated the area’s artistic potential.

Following in Cole’s footsteps came a new generation of artists who were captivated by the region’s rugged charm. One of the earliest and most enduring was Benjamin Champney, born on November 20, 1817, in New Ipswich, New Hampshire. Champney studied in Boston and Paris, yet he found his life’s work back home in the mountains of his youth. His arrival in the region in the 1850s marked the beginning of a more sustained and prolific period in White Mountain painting.

These early pioneers set up their easels in iconic locations like Mount Washington, Franconia Notch, and Crawford Notch. These natural landmarks became visual shorthand for grandeur, permanence, and American exceptionalism. Artists such as Jasper Cropsey, Sanford Gifford, and John Frederick Kensett, all of whom were associated with the Hudson River School, made repeated visits to the area. Their works often blended faithful renderings of topography with subtle romantic embellishments to heighten emotional impact.

Many of these artists worked independently, but their shared admiration for the region fostered a sense of collective purpose. The early White Mountain paintings were more than studies of nature; they were visual sermons, communicating a reverence for divine creation. Their popularity grew not only due to artistic merit but also because of the rise of lithographic reproduction, which allowed these images to be widely distributed. By the mid-19th century, White Mountain art had become an established and respected branch of American landscape painting.

Benjamin Champney and the Heart of the Movement

Benjamin Champney remains the single most iconic figure of the White Mountain art movement. Born in 1817, he grew up in New Hampshire before receiving formal art training at the Boston Academy of Design and later studying in Europe during the 1840s. His exposure to European academic painting, especially the French landscape tradition, greatly refined his technique. Yet despite his success abroad, Champney was drawn back to New Hampshire, believing that its scenery offered artistic riches equal to any European view.

In 1853, Champney settled in North Conway, a village nestled in the shadow of Mount Washington. That same year, he married Elise Jones, a woman he had met during his time in Boston. North Conway became both his home and the informal capital of White Mountain art, drawing dozens of painters who followed Champney’s lead. From his home studio, Champney painted prolifically and mentored younger artists, establishing a seasonal artistic colony that remained active for decades.

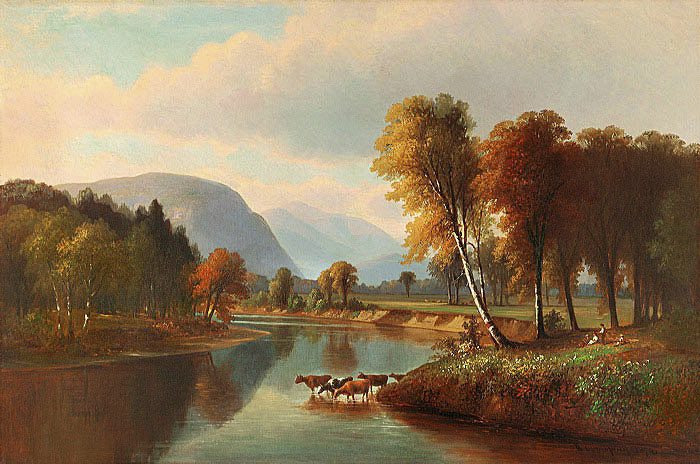

Champney’s works were known for their clarity, precise use of light, and harmonious compositions. He often employed a balanced approach to perspective, placing trees or rocks in the foreground to draw the viewer into expansive vistas beyond. His 1855 painting Mount Washington from North Conway is among his most celebrated, capturing not just the mountain but the sense of reverence it inspired. His art was less about idealization and more about spiritual awe rendered with technical skill.

Though Champney passed away in 1907, his legacy endured through the many artists he influenced and the body of work he left behind. He published his memoir, Sixty Years’ Memories of Art and Artists, in 1900, providing invaluable insight into the development of White Mountain art. His role was not merely as a creator but as a curator of the movement, ensuring that it had both structure and sustainability. His life bridged the Old World academic tradition and the uniquely American vision of the New England wilderness.

The Artist Colonies and Collaborative Spirit

As the White Mountain region became more accessible, seasonal artist colonies began to form, particularly in North Conway and nearby Jackson. These informal yet vibrant communities brought together painters, writers, and intellectuals each summer. Many artists stayed at inns or boarding houses like the Thorn Mountain House, where conversation over supper often revolved around artistic technique and theology. These gatherings created a dynamic environment where ideas flowed as freely as the nearby mountain streams.

Among the notable figures who participated in these colonies were Sanford Gifford, known for his golden light effects, and John Frederick Kensett, whose tranquil compositions helped define Luminism. Jasper Cropsey, another Hudson River School painter, frequently painted the White Mountains and shared techniques with fellow visitors. While competition existed, it was often tempered by mutual respect and a shared love of the subject matter. These artists viewed themselves not as rivals, but as stewards of a divine landscape.

In many ways, these colonies were American equivalents of the French Barbizon School, emphasizing direct observation of nature and the camaraderie of creative minds. Exhibitions were sometimes held in local hotels or Boston galleries, drawing collectors from the cities who were eager to acquire original images of the New England wilderness. The social element of these colonies cannot be overstated. Through marriages, partnerships, and friendships, the artists forged connections that often lasted a lifetime.

One of the lesser-known but important contributors was Harriet Randall Lumis, who, though she painted later in the tradition, carried forward the values of the original movement. Women artists were not as prevalent in the early years, but by the 1870s, they began to make their mark as well. These artists benefited from the nurturing environment established by their male predecessors. The White Mountain colonies provided them with not only inspiration but also the credibility to pursue artistic careers in a male-dominated field.

Techniques, Materials, and Landscape Ideals

White Mountain artists typically worked in oil on canvas, a medium that allowed for both vivid color and intricate detail. Many painters made quick pencil or watercolor sketches in the field and then completed their canvases in studio settings, often during the winter months. Their approach emphasized clarity and precision, rejecting the more abstract trends developing in Europe. The goal was not only to replicate the view but to elevate it—highlighting its emotional and spiritual power.

Compositional elements were crucial in creating these evocative landscapes. Foreground elements like leaning trees or rocky ledges often framed central vistas, drawing the eye toward dramatic mountain peaks or meandering rivers. Light was used symbolically—sunrises over Mount Washington, for example, were often rendered as metaphorical representations of hope and divine guidance. Painters sometimes included small human figures, like hikers or shepherds, to offer scale and reinforce the grandeur of nature.

The philosophical backdrop of these works was deeply rooted in the Protestant worldview that dominated New England at the time. Nature was seen as God’s second book, after Scripture—a manifestation of His wisdom and power. Painters like Champney and Kensett reflected this belief in their reverent depictions of untouched wilderness. Their work often walked the line between realism and idealism, aiming to show the world not just as it was, but as it ought to be.

Although the White Mountain School shared similarities with the Hudson River School, it had a more intimate and regional character. Where the Hudson River School might present the sublime as grand and often foreboding, White Mountain art tended toward the pastoral and contemplative. Artists strove to capture fleeting atmospheric effects—mist over valleys, the golden hue of twilight, or the stark clarity after a storm. These technical choices helped define a uniquely American school of landscape painting.

The Decline and Revival of Interest

After the Civil War ended in 1865, American tastes in art began to change. The optimism and national pride that had fueled interest in landscape painting gave way to more urban and modernist sensibilities. Realism, Impressionism, and eventually abstraction began to eclipse the careful naturalism of the White Mountain artists. By the 1880s, even the most skilled landscape painters found it difficult to command the same level of public interest or financial support.

This shift was influenced by broader cultural movements. As America industrialized, its artistic gaze turned from wilderness to city streets, from mountain grandeur to human struggles. The European avant-garde movements, especially Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, began to influence young American painters. Artistic training shifted from outdoor sketching to academic studios and avant-garde salons. As a result, the White Mountain tradition began to appear old-fashioned and overly sentimental.

However, in the early 20th century, regional pride and nostalgia for the 19th-century landscape sparked a revival of interest in these earlier works. Museums in New England, such as the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire, and the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College, began to acquire and display White Mountain paintings. Collectors and historians reevaluated the technical skill and cultural value embedded in these pieces. The works were now appreciated not just for their beauty but as historical documents of a pre-industrial America.

By the late 20th century, initiatives like White Mountain Art & Artists, launched in the 1990s, began to catalog and promote the movement. Online archives, regional exhibitions, and academic studies gave the genre new life. Through these efforts, White Mountain art reclaimed its rightful place in American art history. The movement, once nearly forgotten, was now seen as a vital expression of national identity and spiritual vision.

Legacy and Modern Appreciation of White Mountain Art

Today, the legacy of White Mountain art lives on in galleries, museums, and private collections across the country. Its paintings are prized not only for their aesthetic beauty but for what they represent—a time when artists sought to portray God’s handiwork in the American landscape. Tourists still flock to the same mountain vistas that inspired Champney and his peers, often unaware that their gaze follows a century-old artistic tradition. Local museums offer tours and educational programs that introduce new generations to this important movement.

Art collectors continue to invest in White Mountain paintings, with some works fetching six-figure sums at auction. Pieces by Benjamin Champney, John Frederick Kensett, and Jasper Cropsey regularly appear in art sales and are prominently displayed in New England homes and institutions. The market has grown steadily, fueled by both historical interest and the enduring appeal of classic American landscape painting. For many, owning a White Mountain piece is akin to holding a piece of national heritage.

Modern artists have also drawn inspiration from this school, adapting its techniques and spiritual perspective to contemporary settings. Plein air painters in New England still venture into the mountains with easels and brushes, working in the very same spots where the original masters once stood. Organizations such as the New Hampshire Historical Society and the New England Plein Air Painters actively promote this heritage. Their work bridges past and present, tradition and innovation.

In the broader cultural sense, White Mountain art has shaped how Americans view their wilderness—not as a threat, but as a sacred trust. These paintings helped cultivate the early conservation ethos that would later fuel national park movements and environmental stewardship. In a world increasingly defined by technology and transience, the enduring beauty of these works reminds us of what is permanent, what is noble, and what is worth preserving.

Key Takeaways

- White Mountain art originated in 19th-century New Hampshire as a regional offshoot of the Hudson River School.

- Benjamin Champney was the movement’s central figure, establishing an artist colony in North Conway.

- The style emphasized spiritual reverence for nature, technical precision, and national pride.

- After a decline in popularity, the movement saw revival in the 20th century through museums and collectors.

- Today, the legacy endures in modern plein air painting and cultural tourism across New England.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Benjamin Champney and why is he important?

He was a leading White Mountain artist who founded the North Conway artist colony and helped define the movement’s style. - What themes are common in White Mountain paintings?

Common themes include divine beauty, wilderness purity, and national pride rooted in the American landscape. - How is White Mountain art different from the Hudson River School?

While similar in philosophy, White Mountain art is more regionally focused and emphasizes intimate, contemplative scenes. - Why did interest in White Mountain art decline after the Civil War?

Changes in taste, industrialization, and modernist trends led to a shift away from traditional landscape painting. - Where can I see White Mountain paintings today?

They are housed in regional museums like the Currier Museum and can be found in both private collections and public exhibitions.