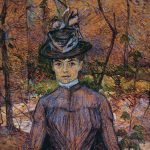

At the turn of the 20th century, Paris was alive with rebellion, decadence, and artistic revolution. And no one embodied the chaos of the Belle Époque more fully than Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Born into nobility but drawn to the smoky underworld of Montmartre, Lautrec lived fast, painted obsessively, and drank constantly. Among his many excesses was one of the strangest, strongest cocktails ever devised: the Tremblement de Terre, or Earthquake.

A lethal mix of half absinthe and half cognac, the Earthquake was not a drink meant to be savored—it was meant to knock you off your feet. As its name suggests, the concoction was like a tremor through the nervous system: jarring, disorienting, and unforgettable. Lautrec didn’t just invent it—he practically lived on it, dragging the drink with him from smoky cafés to backroom brothels, often storing it in a hollowed-out cane so he could sip unnoticed, even during formal dinners.

The Earthquake was more than just a beverage. It was a symbol of a crumbling social order, a personal rebellion against aristocratic expectations, and a dangerously intoxicating way to live on the edge of genius and madness.

The Recipe: Simplicity with a Side of Self-Destruction

The formula for the Earthquake couldn’t be simpler—or more devastating:

- 1 part absinthe

- 1 part cognac

- Served neat in a wine goblet or wide glass

Absinthe, often called “the green fairy,” was infamous for its high alcohol content and alleged hallucinogenic properties. At the time, most absinthes ranged from 45% to 74% alcohol, and they often contained traces of thujone, a chemical compound from wormwood thought to induce visions, anxiety, or madness. Cognac, though more refined, typically sat at a solid 40% ABV. Combined, they formed a concoction with the flavor of an herbal fireball and the impact of a runaway carriage.

Toulouse-Lautrec often downed several Earthquakes in one sitting, reportedly drinking as though it were nothing stronger than a table wine. Some accounts suggest he would serve the cocktail to friends without warning, taking pride in their reactions—ranging from astonishment to blackouts. He was known to insist that drinking Earthquakes before a night out “set the mood,” though the mood often included slurred poetry, spontaneous sketching, and erratic behavior.

Some 19th-century bar guides caution against mixing absinthe with other spirits due to its potency. Lautrec didn’t care. For him, the Earthquake wasn’t about balance or safety—it was about obliteration, both physical and emotional. And in that destruction, he claimed to find inspiration.

Absinthe: Liquid Muse or Green Madness?

The Earthquake’s central ingredient—absinthe—was more than just a drink. It was a cultural lightning rod. Nicknamed la fée verte (“the green fairy”), absinthe was adored by poets, painters, and anarchists. Yet it was also blamed for murder, psychosis, and moral decay. By the 1890s, it had become the scapegoat for everything decadent about modern life in France.

Absinthe’s alleged hallucinogenic effects came under scientific scrutiny after several violent incidents. The most infamous was the 1905 case of Jean Lanfray, a Swiss man who murdered his wife and children after consuming large amounts of alcohol—including absinthe. Though he had also consumed wine, brandy, and crème de menthe, anti-absinthe campaigners seized on the case to fuel moral panic. By 1915, absinthe was banned in France and across much of Europe and the U.S.

Modern science has since debunked many of the myths around thujone and hallucinations. But in Lautrec’s day, absinthe was feared and revered in equal measure. Mixed with cognac, it amplified every effect—especially when consumed in large quantities. For some, it opened creative doors. For others, it slammed them shut.

Lautrec’s generation romanticized the drink, associating it with rebellion and brilliance. Yet its dangers were real. Chronic absinthe drinkers often suffered from insomnia, tremors, and liver failure. Lautrec, who started drinking heavily in his twenties, exhibited all of these symptoms by his mid-thirties.

Sordid Nights and Studio Binges

Lautrec’s life was built around his drinking habit. He was often seen stumbling through Montmartre late at night, moving between the Moulin Rouge, Le Chat Noir, and various houses of ill repute. His studio was littered with half-finished glasses, smudged sketches, and crumpled paper soaked in spilled alcohol. Models recalled that he was always drinking—during painting sessions, meals, and even while bathing.

The Earthquake wasn’t a solo indulgence. Lautrec loved to serve it at gatherings and dinners, often in defiance of social expectations. In one notorious instance, he brought a bottle of the mix to a formal banquet and served it in place of wine, prompting gasps and laughter. On another occasion, he reportedly challenged a fellow artist to an “Earthquake duel,” where the first to pass out would lose. Both men blacked out; no one remembered who won.

He also kept a personal reserve of the cocktail inside a hollowed-out walking cane—an item he carried due to his short stature and fragile legs. Witnesses say he would casually unscrew the cane’s handle, pour himself a glass of the green-brown mixture, and drink as if nothing were unusual. The cane allowed him to drink discreetly during official functions and meetings, even in the presence of patrons.

These antics, while amusing to some, signaled deeper problems. Friends worried about his health, noting that he often seemed confused, agitated, or deeply depressed. Yet Lautrec refused to stop. He viewed drinking—especially the Earthquake—not as a vice, but as a necessity for creation.

Downward Spiral: From Brilliance to Breakdown

By 1897, Toulouse-Lautrec’s body was failing. Years of alcoholism had damaged his liver, weakened his immune system, and wrecked his nervous system. He began experiencing vivid hallucinations, often claiming to see spiders crawling on his sheets or phantom animals dancing on his walls. His speech became slurred, and his once sharp wit turned unpredictable and harsh.

In 1899, after a public episode in which he collapsed while trying to draw at a café, his family and friends had him committed to a private asylum in Neuilly. There, he suffered through detoxification and periods of deep confusion. He continued to sketch, even during his recovery, producing a series of haunting drawings—many of which reflect confinement and madness.

He was released later that year and briefly returned to painting, but the damage was permanent. He died in 1901 at the age of 36, likely from complications related to alcoholism and syphilis. At the time of his death, his career had already begun to decline. It would take decades before his work was rediscovered and celebrated widely again.

Today, the Earthquake stands as a relic of that self-destruction—a drink that matched its inventor’s chaotic, brilliant, and tragic life.

Modern Revival: Curiosity, Not Consumption

Though the Earthquake is rarely served today, it has seen occasional revivals among bartenders drawn to vintage cocktail culture. It’s often presented more as a novelty or historical experience than a recommended beverage. Most modern versions use pastis or absinthe substitute due to legal restrictions or availability, though authentic absinthe is legal again in much of the West.

Because of its intensity, many bartenders dilute the original 1:1 ratio with water or ice. Some use a sugar cube or citrus peel to soften the flavor. But even with these modifications, it remains one of the strongest classic cocktails ever recorded.

A few modern establishments in Paris and New Orleans have featured the Earthquake on specialty menus, usually with a disclaimer. Drinkers are advised to proceed with caution. While a single Earthquake may not summon hallucinations, it can certainly derail an evening.

In this sense, the cocktail still does what Lautrec intended: It removes inhibition, breaks barriers, and crashes through polite society like a sudden tremor.

Key Takeaways

- Toulouse-Lautrec invented the “Earthquake” cocktail—equal parts absinthe and cognac—as a shockingly strong drink.

- Absinthe, a key ingredient, was believed to cause hallucinations and was later banned in France and other countries.

- Lautrec carried the drink in a hollow cane and served it at parties, banquets, and even formal events.

- Years of heavy drinking, including Earthquakes, led to mental collapse and institutionalization by 1899.

- Today, the Earthquake is rarely served but remembered as one of history’s wildest and most dangerous cocktails.

FAQs

- What does the Earthquake cocktail taste like?

It has a powerful, herbal taste with a sharp burn—bitter, fiery, and not for the faint of heart. - Did Toulouse-Lautrec really drink it from a cane?

Yes. He had a custom-made hollow cane that stored liquor, allowing him to drink discreetly anywhere. - Why was absinthe banned?

It was blamed for hallucinations, madness, and crimes—though these effects were likely exaggerated. - How much alcohol is in an Earthquake cocktail?

Depending on the absinthe and cognac used, it can easily exceed 60% alcohol by volume. - Is it safe to drink today?

In moderation, with legal absinthe substitutes, it can be consumed safely—but it remains extremely strong and is not recommended as a casual drink.