The Silk Road was more than a trade route—it was a bridge between civilizations. From 130 BC to the 15th century AD, it connected China with Persia, the Islamic world, and Europe through land and sea routes. While merchants exchanged spices, silk, paper, and porcelain, they also carried ideas, religious beliefs, and artistic styles. This cultural exchange helped shape visual traditions across Asia and the Mediterranean.

As goods traveled west, so did Chinese painting styles, Buddhist imagery, and porcelain techniques. In return, Greco-Roman sculpture, Persian manuscripts, and Islamic design made their way east. Local artists didn’t just copy what they saw—they blended it with their own traditions. The result was something entirely new: hybrid forms that still influence art today.

Major cities along the Silk Road became artistic centers. Dunhuang’s Buddhist caves, Samarkand’s blue-tiled buildings, and Baghdad’s illustrated manuscripts all bear traces of international influence. Artisans from different backgrounds worked side by side in these hubs, learning from one another and creating unique works that reflected the blend of cultures.

This article explores how the Silk Road shaped global art. It traces the movement of visual ideas and techniques, showing how trade didn’t just change economies—it changed how people saw the world and expressed beauty across time and borders.

The Geographic and Cultural Scope of the Silk Road

The Silk Road stretched thousands of miles across mountains, deserts, and seas, connecting people from the Chinese capital of Chang’an to the Mediterranean port of Antioch. The overland route passed through Central Asia, Persia, and Mesopotamia, while the Maritime Silk Road extended through Southeast Asia, India, and the Arabian Peninsula. These trade networks evolved over centuries, depending on shifting empires, climate conditions, and political alliances. Despite challenges, the flow of goods and culture remained steady for over 1,500 years.

The road wasn’t just about commerce. It brought together diverse peoples who shared stories, art, and religion. Ideas from the Buddhist, Islamic, Christian, and Zoroastrian worlds moved freely. Traders brought fabrics, pottery, and paintings to distant lands where they inspired local artists. As a result, art along the Silk Road became a rich blend of styles, themes, and techniques drawn from many different civilizations.

Key Trade Routes and Cultural Intersections

Cities along the route became cultural crossroads. Samarkand, located in modern-day Uzbekistan, thrived as a meeting point for Persian, Chinese, and Turkic traditions. Palmyra in Syria and Merv in Turkmenistan also grew into influential centers of exchange. Artists in these places drew inspiration from multiple sources, combining them into new artistic forms.

UNESCO has designated over 30 Silk Road sites as World Heritage Sites. These include Dunhuang in China, a center for Buddhist cave art, and Merv, a Central Asian city that once rivaled Baghdad. Their preserved artworks show how styles from East and West merged, leaving behind a legacy of shared visual culture.

Chinese Art and Influence: Export and Evolution

China’s role in the Silk Road was both foundational and transformational. It was the source of many prized goods—silk, porcelain, and lacquerware—but it was also deeply influenced by foreign ideas. During the Han and Tang dynasties, Chinese artists encountered Central Asian, Indian, and Persian motifs. These influences helped shape everything from sculpture to painting and even architecture. The process of artistic exchange enriched native styles with new forms and meanings.

Silk was China’s most famous export, and it served not only as clothing but also as a canvas for artistic expression. Painted silks showed court scenes, myths, and religious imagery. Chinese porcelain, especially during the Tang (618–907 AD) and Song (960–1279 AD) periods, gained admiration abroad for its beauty and durability. In return, Chinese artists absorbed elements of foreign aesthetics, especially as Buddhism entered China from India through Central Asia.

Silk, Porcelain, and Buddhist Iconography

The Mogao Caves at Dunhuang provide the clearest example of Chinese art shaped by Silk Road exchange. From the 4th to the 14th century AD, artists painted thousands of murals in these caves, mixing Indian Buddhist themes with Chinese landscapes and Persian-style dress. Some figures even bear Greco-Roman features, showing how deeply cultural blending influenced religious art.

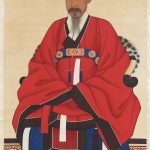

Chinese court painters in the Tang dynasty were also affected by foreign contacts. They began to depict foreign envoys, exotic animals, and Central Asian musicians in court scenes. These paintings didn’t just record trade—they reflected admiration for the cultures China encountered, showing a more cosmopolitan artistic vision.

Central Asia as a Cultural Conduit

Central Asia was not just a stop along the Silk Road—it was the middle ground where cultures merged. This region included the Sogdian cities, the Kushan Empire, and nomadic groups like the Turks and Mongols. These peoples acted as go-betweens, facilitating the movement of artists and art across Eurasia. Their own art reflected the diversity of influences that passed through their lands, making Central Asia a place of artistic innovation.

Sogdian merchants, who dominated trade from the 4th to the 8th centuries AD, were skilled diplomats and cultural translators. Their murals in cities like Panjikent show Persian gods, Indian dancers, and Chinese textiles all in one frame. These works were not accidental mixtures but intentional fusions. Artists chose what to borrow and adapted foreign elements into local visual stories.

Sogdians, Nomads, and Artistic Syncretism

Nomadic groups also contributed to artistic exchange. The Scythians and later the Turks and Mongols used portable art forms—embroidered textiles, painted tents, and carved saddles—that traveled with them. Their styles influenced both sedentary and nomadic cultures, spreading animal motifs, spiral designs, and geometric patterns across the steppe and beyond.

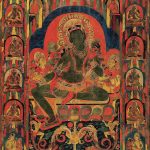

The Kushan Empire (1st–4th century AD) played a critical role in merging Greco-Roman, Indian, and Central Asian art. Buddhist sculpture from this time—especially the Gandhara style—shows Buddha figures with Roman-style robes and realistic features. This hybrid form traveled into China and became a model for Buddhist imagery for centuries.

The Persian Empire’s Artistic Adaptations

Persia, located between China and the Mediterranean, was perfectly positioned to absorb and reinterpret artistic influences. From the Achaemenid Empire through the Sassanid and Timurid periods, Persian art incorporated styles from both East and West. Luxurious textiles, detailed manuscripts, and intricately decorated ceramics reflected the region’s openness to external ideas. Artistic forms from China and India found new life in Persian workshops.

Persian artisans were known for their ability to blend foreign elements into their own traditions. They adopted motifs like dragons, clouds, and floral designs from Chinese textiles and adapted them into carpets, architecture, and metalwork. Court patronage played a major role. Rulers often welcomed foreign artists and actively encouraged artistic fusion.

Persian Miniatures and Cross-Cultural Symbolism

The Timurid period (14th–15th century AD) saw a flourishing of Persian miniature painting. One of the most famous artists of this time, Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād (c. 1450–1535), worked in Herat and later Tabriz. His paintings combined Persian narrative styles with Chinese-inspired landscapes, curved clouds, and expressive gestures. Behzād’s art set the standard for manuscript illustration across the Islamic world.

Under the Mongol Ilkhanids and later the Timurids, Persian workshops sometimes hosted Chinese artists or copied their styles directly. Decorative borders, flowing lines, and naturalistic details became common. These blended styles influenced not only Persian art but also the Ottoman and Mughal empires, proving that Silk Road exchange reshaped the visual identity of an entire region.

Artistic Transmission to the Islamic World and Byzantium

The Islamic world was one of the great inheritors of Silk Road artistic exchange. From the 7th century onward, Islamic dynasties absorbed and reinterpreted styles from China, India, Persia, and the Greco-Roman world. The Abbasid caliphate (750–1258 AD), centered in Baghdad, actively promoted artistic development, attracting craftsmen and intellectuals from across Asia. Through trade and diplomacy, visual techniques from the East shaped Islamic architecture, manuscripts, and ceramics.

One of the most important imports was the Chinese method of paper-making, introduced to the Islamic world after the Battle of Talas in 751 AD. This allowed for the production of books, manuscripts, and calligraphy on a much larger scale. Chinese pigments and decorative styles also influenced manuscript illumination, especially in border decoration and stylized clouds. Glazed ceramic techniques, including cobalt blue painting, were adapted by Islamic potters to produce lusterware and tile mosaics.

Calligraphy, Manuscripts, and Architectural Motifs

Islamic architecture saw a significant transformation through these influences. The widespread use of blue-and-white tiles, floral arabesques, and repeating geometric patterns can be traced back to Chinese and Central Asian motifs. In cities like Samarra, Isfahan, and Cairo, buildings displayed artistic borrowings that celebrated both Islamic identity and global sophistication. These artistic imports were not seen as foreign—they were celebrated as refined and cosmopolitan.

Byzantium, located at the western edge of the Silk Road, also absorbed artistic elements from the East. Byzantine silk production was inspired by Chinese models, and imperial textiles often featured motifs like the lotus and the phoenix. Decorative arts, including ivory carving and mosaic design, also reveal distant echoes of Central Asian and Persian styles. These exchanges helped maintain a shared visual vocabulary from Xi’an to Constantinople.

Mediterranean Reception: The European Renaissance and Eastern Art

By the late medieval period, Eastern art objects were arriving in Europe through overland and maritime trade routes. Italian ports like Venice and Genoa became major entry points for Chinese porcelain, Islamic textiles, and Persian manuscripts. These items were collected by aristocrats and church officials not just for their beauty but for their exotic origins. The growing interest in foreign objects contributed to a new way of thinking about beauty, luxury, and artistic technique.

European artists in the early Renaissance began to incorporate motifs and materials that had arrived from the East. The influence was especially visible in tapestry design, illuminated manuscripts, and decorative art. Textiles woven with Chinese dragons or Persian hunting scenes were integrated into church robes, palace décor, and costume design. These were not random additions—they reflected a growing awareness of a broader visual world.

Collecting “Exotic” Art and Ideas

Gentile Bellini (c. 1429–1507), a Venetian painter, traveled to Constantinople in 1479 to serve at the Ottoman court of Sultan Mehmed II. His portraits and sketches captured Eastern architectural features and ceremonial dress, adding subtle Oriental elements to European painting. Though not directly influenced by Chinese models, his work reflected Europe’s growing exposure to the artistic styles moving along the Silk Road.

Chinoiserie, which became fashionable in the 17th and 18th centuries, was rooted in these earlier encounters. As more porcelain, lacquerware, and silk reached Europe, artists and decorators copied and reinterpreted Asian styles. Though not always accurate, these adaptations reflected centuries of admiration and influence. The Silk Road had long since faded, but its artistic legacy remained deeply embedded in the European imagination.

Long-Term Legacy and Modern Recognition

The influence of the Silk Road on global art did not end with the closing of trade routes. Its legacy lives on in museum collections, architectural styles, and modern artistic revivals. In the 20th and 21st centuries, historians, artists, and curators have worked to rediscover and highlight the Silk Road’s cultural impact. Exhibitions, scholarly research, and cultural exchanges continue to explore how deeply these ancient routes shaped the world’s artistic heritage.

Modern artists often draw on Silk Road themes in their work. Chinese contemporary artist Ai Weiwei has referenced trade, cultural blending, and porcelain in his installations. His pieces reflect not only the aesthetics but also the historical tensions of East-West relations. In Central Asia, artists continue to use traditional textile patterns that trace their origins back to Sogdian and Persian designs passed along the Silk Road.

Silk Road Influence in Contemporary Art and Scholarship

Museums like the British Museum in London and the National Museum of China have curated major exhibitions on Silk Road art. These shows highlight objects like Buddhist cave murals, Islamic ceramics, and Persian manuscripts that illustrate the depth of cross-cultural exchange. They also emphasize the shared ownership of cultural achievements that transcend modern borders.

UNESCO’s Silk Roads Programme promotes international cooperation by identifying cultural sites, publishing research, and supporting educational projects. This work helps preserve and share the Silk Road’s artistic legacy with new generations. The idea of the Silk Road today represents more than trade—it symbolizes global creativity, mutual respect, and a shared visual heritage that continues to inspire.

Key Takeaways

- The Silk Road connected distant civilizations through art, not just trade goods.

- Chinese silk and porcelain influenced Persian, Islamic, and European art forms.

- Central Asia served as a creative hub where Indian, Persian, and Chinese styles blended.

- Persian miniatures and Islamic architecture incorporated East Asian motifs.

- The legacy of artistic exchange continues in modern exhibitions and contemporary art.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How did the Silk Road influence Chinese art?

It introduced foreign styles and religious imagery that shaped Buddhist murals, court painting, and decorative design. - What role did Central Asia play in art exchange?

Central Asia was a middle ground where Indian, Persian, Chinese, and Greco-Roman elements merged in painting, sculpture, and textiles. - How did the Islamic world adopt Chinese art forms?

Through paper-making, glazing, and decorative motifs, Islamic artists adapted Chinese techniques into their manuscripts and architecture. - Did European artists use Silk Road influences during the Renaissance?

Yes, Eastern textiles and styles appeared in paintings, tapestries, and decorative arts, especially in Italy and Spain. - What is the modern legacy of Silk Road artistic exchange?

Its legacy lives on in museums, scholarly work, and modern artists who explore cultural blending and historical trade themes.