Long before Lithuania became a battleground of empires or a stronghold of Baroque splendor, it was home to one of Europe’s last surviving pagan cultures. The art of ancient Lithuania is not easily captured in monumental stone or grand canvases. Instead, it whispers through amber carvings, symbolic patterns etched into pottery, and the enduring rituals woven into folk tradition. This is a chapter of art history where mythology and material culture merge, offering a rare look at a Baltic worldview largely untamed by classical or Christian frameworks.

The Baltic Tribes and Their Cosmology

The earliest inhabitants of the land now known as Lithuania were Baltic tribes, a branch of the Indo-European family with a language group that still survives in modern Lithuanian and Latvian. These communities, scattered across forests, rivers, and coastal plains, developed an animistic worldview where nature was both sacred and sentient. Trees had spirits, stones bore wisdom, and rivers flowed with divine intent. Their art reflects this spiritual ecology.

Archaeological discoveries from the Neolithic and Bronze Age periods reveal a deep reverence for natural forms. Zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures—small, often carved from bone, amber, or clay—served religious or protective functions. These objects were not mere decorations; they were talismans, believed to hold power, used in fertility rites or as guardians of the home.

Amber: The Gold of the Baltic

Amber was not only a material of aesthetic value but also a central element of trade and spiritual practice. Baltic amber, known for its warm hues and clarity, was worked into pendants, amulets, and beads. Some of the earliest Lithuanian amber carvings date back to the Mesolithic era, over 7,000 years ago.

Amber’s appeal was not just visual. Ancient Baltic cultures believed it to be imbued with protective and healing properties. The Greek historian Tacitus mentioned the Baltic peoples in Germania (circa 98 CE), noting their use of amber and their mysterious customs. Amber found its way down to the Mediterranean via the Amber Road, a trade route that linked the Baltic Sea to the Roman Empire. This connection allowed for cross-cultural influences, though Baltic tribes remained relatively autonomous, maintaining unique visual styles even when influenced by outside contact.

Ornament and Meaning in Everyday Objects

Unlike classical Western art, which often separates function from aesthetics, early Lithuanian art blurred those boundaries. Everyday objects—belt buckles, brooches, horse harnesses—were meticulously decorated with intricate patterns, including spirals, sun motifs, and tree-of-life symbols. These recurring designs weren’t purely ornamental; they encoded cosmological beliefs and social status.

Textile patterns from the Iron Age display remarkably complex designs, passed down across generations. In fact, many of these motifs persist in Lithuanian folk costumes today, representing an unbroken visual language from the pre-Christian era. The act of weaving itself held symbolic weight—considered a sacred practice tied to the feminine divine, it was both labor and liturgy.

Ritual Sites and Symbolic Landscapes

Sacred groves, hillforts, and stone circles served as focal points for ritual and communal gatherings. The most famous of these is the Šatrija Hill in Samogitia, which, according to legend, was a gathering place for witches and a powerful pagan site. The layout of these sacred spaces often aligned with solar and lunar cycles, reinforcing the importance of celestial rhythms in Baltic spirituality.

The landscape itself was considered animate, and this belief is visible in how early art responded to natural forms rather than imposing upon them. Carvings followed the grain of the wood; stones were selected for their natural shapes and enhanced minimally. This ecological humility is a hallmark of pre-Christian Baltic art—a form of collaboration with nature, not conquest.

The Shamanic Figure in Baltic Lore

One recurring image in reconstructed interpretations of Baltic spiritual life is that of the shaman—an intermediary figure who used music, dance, and sacred objects to traverse spiritual realms. Though direct evidence is scarce due to the lack of written records, comparative mythology and ethnographic studies suggest a vibrant ritual life involving masks, chants, and costume. Some of the earliest masks and animal figurines found in Lithuanian bogs and burial sites hint at these shamanic traditions.

In these performances, art became alive—something experienced communally rather than viewed statically. This ephemeral, performative dimension of ancient Lithuanian art is one of its most distinctive qualities, yet the most elusive to document.

Transition and Suppression

By the time Christianity arrived in Lithuania (officially in 1387, the last country in Europe to convert), much of this pagan artistic tradition had already been marginalized or reinterpreted through Christian lenses. Sacred groves were burned, wooden idols destroyed, and stone carvings repurposed. Yet, the memory of pagan art survived—often underground, sometimes integrated subtly into Christian art through hybrid symbols.

The famous Lithuanian wooden crosses (kryždirbystė), for example, blend Christian and pre-Christian motifs. They are often adorned with floral, sun, and tree-of-life patterns—resonances of an earlier spiritual vocabulary. In this way, the spirit of ancient Lithuanian art persists, not in museums or galleries, but in folk tradition, ritual, and landscape.

Medieval Lithuania: Crossroads of Paganism and Christianity

Lithuania’s medieval period was unlike that of any other European country. While most of the continent had long since embraced Christianity by the 10th century, Lithuania persisted in its pagan traditions well into the 14th century. This delay was not the result of isolation or cultural stagnation, but rather a sophisticated strategy of religious resistance and political pragmatism. As such, the art of medieval Lithuania is a fascinating amalgam—part sacred forest and part Gothic cathedral, part ancient rite and part emerging European identity.

This duality is the key to understanding Lithuanian visual culture during the Middle Ages. Art was not simply a reflection of aesthetic trends but a battleground where competing worldviews contended. The period between the 13th and 15th centuries—when Lithuania transitioned from a powerful pagan Grand Duchy to a Christianized European state—produced a rich tapestry of visual forms that speak to both continuity and rupture.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania: A Pagan Power in a Christian World

In the 13th century, Lithuania emerged as a major political force in Eastern Europe. Under the leadership of Mindaugas, who was crowned as King of Lithuania in 1253, the state began its first experiments with Christianity, although often for strategic rather than spiritual reasons. Mindaugas’s baptism and coronation were seen as diplomatic moves to forge alliances and ward off crusading knights.

However, after Mindaugas’s assassination in 1263, Lithuania reverted to pagan rule for more than a century. This return was not a regression but a cultural affirmation. Paganism wasn’t merely tolerated; it was institutionalized. Grand Dukes such as Gediminas and Algirdas presided over a court that supported indigenous ritual and myth while also maintaining diplomatic relations with Christian Europe.

This unique position meant that Lithuanian art in the late 13th and early 14th centuries operated in a liminal space. Stone forts and wooden temples stood alongside imported Christian icons sent by diplomatic partners. Embroidery, jewelry, and architectural ornamentation remained rooted in Baltic symbolism—sun wheels, birds, and serpents—yet slowly began to incorporate foreign motifs, especially from Slavic and Germanic sources.

The Christianization of 1387: A Cultural Turning Point

The official Christianization of Lithuania came in 1387 under Grand Duke Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło), who accepted baptism in exchange for marriage to Queen Jadwiga of Poland and the Polish crown. This marked a seismic shift in Lithuanian art and society. Overnight, religious iconography, previously nonexistent or covert, flooded the visual landscape.

Churches were constructed at a rapid pace, often funded or administered by the Polish crown and Catholic orders. These early churches were typically wooden structures adorned with imported liturgical objects: crucifixes, chalices, illuminated manuscripts, and altar pieces. Lithuanian craftsmen, largely untrained in Christian iconography, initially adapted their existing skills to this new visual vocabulary. This led to fascinating hybrid forms: crucifixes with sun motifs, saints with stylized floral robes, and chalices bearing echoes of pagan metalwork.

Yet Christianization was not universally accepted. In Samogitia, the last region of Lithuania to be officially converted (in 1413), underground pagan practices persisted well into the 16th century. These resistance movements are visible in folk art, which retained pre-Christian symbols under the guise of decorative tradition. Crosses were carved with tree-of-life patterns, and embroidered vestments still bore the eight-pointed star—a solar symbol with roots in Baltic mythology.

Gothic Arrivals and the Rise of Ecclesiastical Art

With Christianity came Gothic architecture. The most notable early example is the Church of St. Anne in Vilnius, a stunning brick Gothic structure completed in the early 16th century. Its delicate spires and pointed arches would have been utterly foreign to the Lithuanian vernacular landscape, which had long favored horizontal lines and organic integration with nature.

But Gothic didn’t simply replace native forms—it collided with them. Lithuanian artisans working on churches and cathedrals often modified imported designs. Brick patterns included local floral motifs; interior decorations incorporated the same geometries seen in ancient textiles and woodcarving. The Lithuanian Gothic style, particularly visible in the Vilnius region, reflects this cultural negotiation.

Ecclesiastical art also included illuminated manuscripts, imported or produced in regional scriptoriums. Many of these texts featured marginalia and embellishments that retained a distinctly non-Christian flavor—stylized birds, beasts, and interlace that recalled pagan decorative traditions.

The Hillforts and Their Legacy

Even after Christianization, the landscape of Lithuania remained dotted with hillforts—some still in use, others left as monuments to the pagan past. These structures, built primarily of earth and wood, had served both defensive and ceremonial purposes. Though not “art” in the traditional sense, they were architectural expressions of Baltic cosmology: elevated, circular, and in tune with astronomical alignments.

After the 14th century, many of these hillforts were symbolically abandoned or transformed. Christian chapels were sometimes built on former sacred sites, a clear act of appropriation and spiritual overwrite. In some cases, however, these sites became pilgrimage centers in their own right, combining Christian rites with older seasonal celebrations—a synthesis rather than an erasure.

Manuscripts and the Latinization of Lithuanian Art

The 15th century saw the growing influence of Latin literacy and Western European aesthetic norms. As more Lithuanians joined the clergy or studied abroad, they brought home illuminated manuscripts, liturgical objects, and artistic techniques. Yet, local adaptations always remained. Handwritten Psalters from this era often include marginal symbols drawn from local folklore, and some Gospel illustrations feature landscapes that resemble the Lithuanian countryside more than the Holy Land.

This tension between imported form and local content is a recurring theme in medieval Lithuanian art. It signals a population that was not passively absorbing European norms but actively reshaping them.

Conclusion: A Culture of Hybridity

The medieval period in Lithuanian art is marked by hybridity—religious, stylistic, and cultural. It was a time when pagan motifs lived on in church vestments, when Gothic towers rose above animistic forests, and when saints shared visual space with solar gods. Lithuanian art did not simply surrender to Christian influence; it negotiated with it, integrated it, and, at times, resisted it.

This unique trajectory offers a valuable counter-narrative to the dominant story of European art history. While Italy was inventing the Renaissance, Lithuania was crafting a visual culture of profound syncretism—a world where the old gods still lingered behind the altar.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania: Art in a Multicultural Empire

By the 15th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had become one of the largest and most culturally diverse states in Europe. Stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, it encompassed not only Lithuanians but also Ruthenians (Belarusians and Ukrainians), Poles, Jews, Tatars, and Germans. This vast expanse was not only a geopolitical anomaly but also a fertile ground for artistic fusion. Lithuanian art during this era was shaped by constant negotiation between ethnic identities, languages, religions, and aesthetic systems.

Art in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was, at its heart, a mirror of pluralism. It was born in princely courts, Orthodox monasteries, Catholic cathedrals, and bustling town guilds. It was expressed in liturgical manuscripts, domestic woodwork, monumental architecture, and the evolving practices of applied arts. What emerged was not a single unified “Lithuanian style,” but a rich layering of traditions.

Vilnius: A Cultural Melting Pot

Founded officially in 1323 by Grand Duke Gediminas, Vilnius quickly developed into the cultural and political heart of the Grand Duchy. Its strategic position between East and West made it a magnet for craftsmen, merchants, scholars, and clergy. By the 15th century, the city was a patchwork of ethnic quarters—Lithuanians, Poles, Jews, Germans, and Ruthenians all living side by side. Each brought their own artistic heritage.

Vilnius architecture during this period reflects a remarkable cohabitation of styles. Orthodox churches in the Byzantine tradition rose alongside Latin Catholic chapels. Gothic cathedrals shared street corners with wooden synagogues and Islamic-inspired Tatar mosques. While the Catholic Church grew in visibility after the Christianization of 1387, the city retained a deep Eastern Orthodox character through its Ruthenian population. This duality produced an eclectic sacred architecture where onion domes and pointed arches could coexist, sometimes within the same district.

Orthodox Iconography and Ruthenian Manuscripts

One of the most influential art forms in the Grand Duchy was the Orthodox icon. Rooted in Byzantine tradition and brought to Lithuania through its Ruthenian territories, icons served as focal points for devotion and conduits of spiritual presence. Painted according to strict canons, they featured elongated saints, golden halos, and stylized landscapes. These icons were often produced in monastic scriptoria and traveled widely, found in village churches as well as princely chapels.

The Liturgical books and illuminated manuscripts from Ruthenian Orthodox communities are particularly significant. Many are written in Church Slavonic and feature elaborate initial letters, vegetal borders, and narrative miniatures. While influenced by Byzantine models, they also integrated local elements—colors reflecting Baltic aesthetics, regional flora in the ornamentation, and depictions of familiar Eastern European landscapes. These books were not just religious objects; they were prestige items, commissioned by nobles to assert both piety and political status.

Catholic Influence and the Gothic Court Aesthetic

Simultaneously, Western European influences were filtering into the Grand Duchy via Polish alliances and Latin Christianity. This was especially evident among the Lithuanian nobility, many of whom adopted Gothic visual language in their court culture. Knights wore armor engraved with floral tracery, while chapels and castles took on pointed windows, ribbed vaults, and rose windows reminiscent of French or German precedents.

The most significant architectural example is Vilnius Cathedral, which evolved from a wooden sanctuary into a brick Gothic structure under Jogaila and Vytautas the Great. Although later remodeled in neoclassical style, its foundations bear witness to the early ambitions of a state seeking both religious legitimacy and aesthetic parity with its European peers.

We also begin to see secular art gaining importance: decorated weapons, luxurious textiles, carved furniture, and personal insignia. The Radziwiłł family, one of the most powerful magnate houses in Lithuania, were early patrons of both religious and courtly art. Their estates became hubs for cultural exchange, commissioning artists from Kraków, Kiev, and further afield.

Jewish and Tatar Contributions

The Jewish communities of the Grand Duchy also played a crucial role in its visual culture, especially in manuscript arts, calligraphy, and synagogue decoration. While no medieval Lithuanian synagogues survive intact, textual evidence and comparative examples from the region suggest painted interiors, symbolic animal motifs, and elaborately designed Torah arks. Jewish scribes and illustrators developed a distinctive style that blended Ashkenazi, Byzantine, and local Slavic influences.

Another often overlooked group is the Lipka Tatars, Muslim communities who had settled in Lithuania from the 14th century onward. Though relatively small in number, they left a legacy in decorative arts, particularly in leatherwork, weaponry, and manuscript binding. Tatar Qur’ans produced in the Grand Duchy were often written in Arabic script but used a phonetic Polish-Lithuanian language—testament to the linguistic hybridity of the region.

Religious Tolerance and Aesthetic Exchange

What made the Grand Duchy of Lithuania unique in medieval Europe was its remarkable (if not always consistent) policy of religious tolerance. The Statute of Lithuania, particularly in its 16th-century versions, allowed for the coexistence of Catholic, Orthodox, Jewish, and Muslim communities. This pluralism extended into visual culture, where forms and techniques migrated across confessional lines.

For instance, Lithuanian Catholic churches sometimes adopted the iconostasis form—a feature typical of Orthodox sanctuaries. Meanwhile, Ruthenian manuscript illuminators began incorporating Gothic foliage and border designs seen in Western prayer books. Artistic labor was not rigidly sectarian; guilds often included craftsmen of diverse backgrounds, and court artists might be commissioned across ethnic lines.

This cross-pollination extended to language, too. Inscriptions in religious and civic buildings might appear in Latin, Cyrillic, Hebrew, and Arabic, depending on context and patronage. It is a testament to the fluid identity of the Grand Duchy that a building in Vilnius might contain a Gothic arch, Orthodox fresco, and Muslim artisan work—all within a few rooms of one another.

Death, Memory, and Artistic Legacy

One of the most revealing artistic forms of the era was the funerary monument. Tombstones in Lithuania’s medieval cemeteries provide a visual language of identity negotiation. Orthodox gravestones display delicate crosses and Cyrillic inscriptions; Catholic ones bear coats of arms and Latin prayers; Jewish headstones are often modest but filled with symbolic carvings—lions, books, menorahs. These tombs tell us how communities chose to remember themselves: not as isolated groups but as intertwined threads in a greater cultural fabric.

By the late 15th century, Lithuania was no longer a frontier state but a regional powerhouse with a cultural identity forged in diversity. Its art bore witness to a complex negotiation between tradition and innovation, sacred and secular, East and West. The Grand Duchy was not merely a space between empires—it was an empire of its own, defined not by domination but by creative synthesis.

Baroque Flourish: Religious and Political Expression (17th–18th Century)

If the medieval period in Lithuania was characterized by eclecticism and cultural negotiation, the Baroque era marked a confident assertion of identity through grandeur. The 17th and 18th centuries were a time of both artistic flowering and political complexity. As part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Lithuania entered into a golden age of religious art and architecture, spearheaded by the Catholic Church, the Jesuit Order, and powerful noble patrons. The visual language of the Baroque—ornate, theatrical, emotional—became the dominant mode through which power, piety, and prestige were expressed.

This period witnessed an extraordinary burst of creativity, particularly in Vilnius, often called the “Jerusalem of the North” and sometimes the “Rome of the East” due to its architectural splendor and abundance of churches. In Lithuanian Baroque, we find a local inflection of a pan-European style—adapted, stylized, and deeply rooted in the regional context.

Baroque and the Catholic Reformation

The rise of Baroque art in Lithuania cannot be separated from the Catholic Reformation. Following the Council of Trent (1545–1563), the Catholic Church sought to reaffirm its spiritual authority through art that inspired awe and devotion. The Jesuits arrived in Vilnius in 1569, bringing with them an aesthetic agenda as much as a theological one. Art, under their guidance, became an instrument of persuasion: it was meant to dazzle the eye, move the soul, and win hearts back to the Church.

The Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Vilnius, built between 1668 and 1676, stands as a masterpiece of this vision. While its exterior is modest, the interior is a tour de force of stucco sculpture. Over 2,000 figures—cherubs, saints, floral garlands, biblical scenes—cascade across every surface in an explosion of white ornamentation. This was not merely decorative excess; it was a spiritual cosmos rendered in plaster, meant to envelop the viewer in divine presence.

Similarly, the Vilnius University complex, heavily influenced by Jesuit architecture, reflects Baroque ideals of order, hierarchy, and grandeur. With its enclosed courtyards, ornate façades, and integrated chapels, it served both as a center of learning and a theater of faith.

Vilnius Baroque: A Distinctive Style

Lithuanian Baroque is not simply a provincial imitation of Italian models. Rather, it developed its own formal language, particularly in architecture. The so-called “Vilnius Baroque” style is distinguished by verticality, elegant curvature, and a subtle balance between ornament and structural clarity. Churches often feature tiered façades, slender towers, and dynamic interplay between concave and convex surfaces.

One of the most iconic examples is the Church of St. Catherine, with its tall, narrow façade and rhythmic columnar design. Unlike the heavy massing typical of Baroque elsewhere in Europe, Vilnius Baroque often feels lighter, airier—almost dancing on its foundations. It reflects both local aesthetic preferences and practical adaptations to the materials and climate of the region.

Noble Patronage and Family Chapels

Much of this flourishing was made possible by the continued patronage of Lithuania’s magnate families, particularly the Radziwiłłs, Sapiehas, and Pac family. These nobles not only funded major churches but also built elaborate family chapels, burial vaults, and private altars.

The Church of St. Theresa, funded by the Pac family, includes one of the most lavish chapels in the city: the Pac Chapel, with its gilded altarpieces, imported marble, and trompe-l’œil ceiling frescoes. These chapels were sites of spiritual devotion, but also dynastic propaganda—filled with heraldic symbols, effigies, and inscriptions that linked noble houses with divine favor.

Sacred Painting and Sculpture

Painting in the Lithuanian Baroque was predominantly religious and often devotional in tone. Altarpieces depicted the Virgin Mary, Christ, and saints in states of ecstasy or martyrdom. Artists were influenced by Italian, Flemish, and Polish painters, and though many works were imported, a local school of religious painters began to emerge in the 17th century. These artists specialized in icon-like images with dramatic lighting, rich color, and theatrical compositions.

The cult of Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn in Vilnius produced one of Lithuania’s most iconic religious images. The painting of the Virgin Mary housed in the chapel above the city gate became a major pilgrimage site. Draped in silver and gold, the image reflects the synthesis of iconographic tradition and Baroque embellishment. It also served as a symbol of unity among Catholics and some Orthodox believers, further testifying to the complex religious landscape of the region.

Sculpture, especially stucco and wood carving, was central to Baroque interiors. Churches featured elaborate pulpits, confessionals, and choir stalls adorned with angels, saints, and intricate vegetal motifs. The expressive realism of these works was meant to blur the boundary between art and life, turning the church into a living sermon.

Monastic Orders as Cultural Engines

The artistic transformation of Lithuania was driven not only by the Jesuits but also by other monastic orders: the Bernardines, Dominicans, Carmelites, and Franciscans. Each established monasteries, schools, and churches throughout the country. These were not isolated spiritual enclaves—they were centers of education, publishing, music, and visual culture.

Many monasteries maintained workshops for bookbinding, icon painting, and sculpture. They trained local artisans, preserved older artistic techniques, and also created a network through which styles and ideas moved between rural parishes and urban centers.

Music, too, was an integral part of this Baroque worldview. Polyphonic choral music performed in gilded chapels created a synesthetic experience—sound, image, incense, and space all working together to transport the worshiper toward the divine.

Secular Expressions of Baroque

While religious art dominated the era, secular Baroque also found expression in noble residences and civic architecture. The Radziwiłł Palace in Vilnius, though now much altered, originally reflected the grandeur of a European court, with banquet halls, portrait galleries, and decorative stucco ceilings.

Portraiture flourished in this context. Lithuanian nobles commissioned likenesses that emphasized lineage, virtue, and status. These portraits were more than vanity; they were political tools, asserting legitimacy and reinforcing ties to the Commonwealth’s aristocratic elite.

Furniture, silverware, and ceremonial garments from this period also reflect Baroque sensibilities—curved lines, ornate detailing, and the use of luxurious materials like velvet, gilded wood, and Venetian glass. Applied arts were not secondary but vital parts of Baroque expression.

Decline and Legacy

The later 18th century saw the beginning of the Baroque’s decline, coinciding with political instability in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Yet its legacy endured. Even as Enlightenment ideas gained ground, Baroque remained the language of ritual, memory, and tradition—especially in rural Lithuania, where Baroque-style wayside chapels and crucifixes remained central to community identity.

The style’s emotional immediacy and theatricality left a lasting imprint on Lithuanian cultural life. Even 20th-century artists, working under Soviet repression, would return to Baroque’s expressive richness as a visual refuge and source of national continuity.

Partitions and Resistance: Art Under Imperial Russia (1795–1918)

The final partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795 marked a profound rupture in Lithuanian history. Absorbed into the Russian Empire, Lithuania entered a period of political repression, forced Russification, and cultural control that would last more than a century. For artists and cultural figures, the era presented a harrowing dilemma: adapt, resist, or disappear. Yet despite—or perhaps because of—these pressures, Lithuanian art developed new strategies of survival and subversion. Folk art flourished as a medium of quiet defiance, religious imagery persisted as a form of national memory, and a generation of artists emerged who laid the groundwork for a modern Lithuanian visual identity.

This was a time when art went underground—literally and figuratively. Formal academies were tightly controlled, religious symbols were policed, and Lithuanian-language publishing was outlawed. But creativity found cracks in the imperial edifice, and within those cracks, a distinct national consciousness began to blossom.

The End of the Commonwealth and the Beginning of Imperial Rule

The Russian Empire’s takeover of Lithuania was not simply an annexation—it was a campaign to remake society in the image of tsarist orthodoxy. Russian became the language of administration; Orthodox churches replaced Catholic institutions; and Polish (which had long been the language of the nobility) was increasingly suppressed. The 1831 and 1863 uprisings—two major rebellions against Russian rule—were brutally quashed, and in their aftermath, cultural institutions were shuttered and thousands were exiled to Siberia.

Artists, like writers and intellectuals, were caught in the crossfire. Religious art—especially Catholic imagery—was scrutinized for its subversive potential. Portraits of national heroes such as Grand Duke Vytautas or King Mindaugas were banned or destroyed. Baroque churches were repurposed or stripped of their ornamentation. Yet despite this—or perhaps because of it—art began to evolve into a tool of resistance.

The Rise of Folk Art as Cultural Repository

One of the most significant developments of this period was the elevation of folk art as a bearer of national identity. As elite culture came under suspicion or fell under imperial control, rural artisans, weavers, woodcarvers, and potters became cultural guardians.

Traditional Lithuanian textile patterns—often used in sashes (juostos), tablecloths, and ceremonial clothing—retained pre-Christian and national motifs. Stylized suns, trees of life, and repetitive geometries carried symbolic meaning, passed down without written documentation. These designs were not simply decorative; they encoded stories, rituals, and a sense of rootedness.

Similarly, wooden crosses, a hallmark of Lithuanian religious folk art, took on renewed significance. Though ostensibly Christian, many of these crosses incorporated ancient pagan symbols. They were erected not only in churchyards but also in fields, forests, and roadside shrines. In a time of political erasure, they stood as physical markers of a cultural continuum. The Russian authorities recognized their subversive potential and at times ordered their destruction—efforts that only increased their significance.

Religious Art as Resistance

Though the Russian Empire attempted to replace Catholic churches with Orthodox ones, religious imagery continued to play a central role in Lithuanian cultural life. Painters of devotional images often worked anonymously or locally, producing altar pieces, icons, and crucifixes that reflected both canonical forms and local stylistic quirks.

One of the most poignant examples of this religious resistance was the continued veneration of Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn. The image survived repeated attempts at suppression and became a rallying symbol for spiritual and national unity. The Virgin Mary, often dressed in rich silver plating, was increasingly identified with the Lithuanian motherland—a visual metaphor that resonated across generations.

Meanwhile, underground presses began producing prayer books, calendars, and illustrated catechisms in the Lithuanian language, often adorned with folk-style borders and naive but powerful religious drawings. These materials were smuggled across the border from East Prussia during the Knygnešiai (book smuggler) movement, further intertwining visual art with the fight for cultural survival.

The Lithuanian Press Ban and Visual Culture

Between 1864 and 1904, the Russian Empire enforced a ban on Lithuanian-language publishing using Latin script—a policy designed to accelerate Russification. In response, the visual became even more crucial. Illustrations, symbols, and decorative art often carried messages that could be understood without words. Patterned sashes, embroidered clothing, and painted wooden boxes were all used to subtly express Lithuanian identity.

Portraiture and historical painting, which had previously been the domain of the nobility, now reemerged with nationalist undertones. Painters began to depict scenes from Lithuania’s medieval past—not for aristocratic clients, but for public consciousness. These images, though often modest in technique, were radical in intent. They resurrected a suppressed past and offered models of resistance and pride.

Emergence of National Romanticism

By the late 19th century, despite—or again, because of—continued political control, a movement emerged that combined visual art with the ideals of National Romanticism. Inspired by similar movements in Finland, Norway, and Poland, Lithuanian artists and intellectuals sought to craft a distinct national visual language rooted in folklore, nature, and history.

While formal institutions like the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg still controlled official education, many Lithuanian artists began to travel abroad—to Kraków, Paris, and Munich—bringing back new techniques and ideas. At the same time, they rejected the cosmopolitan detachment of academic art in favor of a rooted, emotionally resonant style.

Artists such as Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, who would later become a leading figure in Lithuanian painting, began their careers in this climate. Their early work, often rural scenes, peasant portraits, and mythological illustrations, signaled a break from imperial narratives and a turn toward local authenticity.

Photography and Printmaking

Photography also became a potent medium in this period. Studio portraits of peasants in traditional dress, carefully posed and stylized, circulated widely and were used to build an image of an enduring Lithuanian people. Meanwhile, woodcut prints—cheap, reproducible, and ideal for smuggling—were used to illustrate calendars, almanacs, and nationalist texts.

These images were not neutral—they were political acts. A depiction of a peasant mother, a reimagined medieval knight, or a harvest scene could carry coded messages of resilience, land, and identity. The ability to replicate these images and distribute them across a network of underground readers amplified their power.

Artistic Life in Exile

A number of Lithuanian cultural figures, including artists, lived in exile during this period—some by force, others by necessity. In cities like Warsaw, Paris, and Tilsit, they established salons, journals, and galleries that kept Lithuanian art alive outside the empire’s reach.

These expatriate artists often walked a tightrope: speaking to Western audiences about their homeland while maintaining their connection to grassroots Lithuanian culture. They experimented with modernist styles but returned to national themes—an approach that would fully blossom in the interwar period.

Legacy and Preparation for Rebirth

By 1904, when the press ban was lifted, a new generation of artists, writers, and intellectuals had emerged. Though they had been denied institutions, patronage, and official recognition, they had created something arguably more powerful: a visual culture that was inseparable from the idea of Lithuania itself. Their work didn’t just reflect a nation—it imagined one.

This era laid the emotional and aesthetic foundation for the explosion of creativity that would follow independence in 1918. It gave art a new purpose—not merely to decorate or inspire but to endure and resist.

M.K. Čiurlionis and the Symbolist Legacy

The dawn of the 20th century in Lithuania was marked by an artistic awakening, and no figure embodies this transformation more than Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911). Composer, painter, mystic, and visionary, Čiurlionis stands not just as a towering figure in Lithuanian art, but as a singular presence in European Symbolism. His short life yielded a body of work so original and spiritually resonant that it continues to shape the identity of Lithuanian art to this day.

Čiurlionis bridged worlds—between East and West, sound and sight, dream and form. Though he died before Lithuania regained independence in 1918, his work became a wellspring of national pride and creative inspiration. Through his fusion of painting and music, he created an entirely new visual language, one that evoked the cosmic, the mythic, and the deeply personal all at once.

The Early Life of a Polymath

Born in the town of Varėna and raised in the Druskininkai region, Čiurlionis grew up in a deeply musical environment. His father was an organist, and young Mikalojus quickly displayed prodigious talent. By age 14, he was studying piano and composition at the Prince Oginsky Music School in Plungė. He would go on to study at the Warsaw Conservatory, graduating with honors in both composition and organ performance.

But his artistic journey did not stop with music. In Warsaw, Čiurlionis enrolled in the Warsaw School of Fine Arts, where he immersed himself in drawing, painting, and art theory. These two pursuits—music and visual art—were never separate for him. In fact, his paintings were often structured like musical compositions: titled as sonatas, fugues, preludes, and imbued with rhythm, repetition, and movement.

Symbolism and the Inner World

Čiurlionis came of age at the height of Symbolism, a pan-European movement that rejected realism in favor of dreams, intuition, and the exploration of spiritual realities. Symbolist artists sought to suggest rather than describe, to reveal hidden truths through metaphors and archetypes. Čiurlionis found in this movement a perfect vehicle for his metaphysical inclinations.

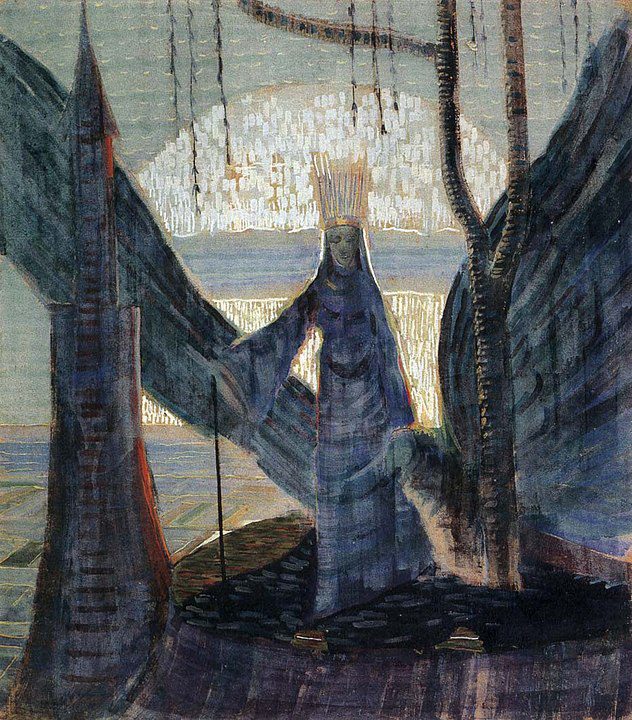

Yet his Symbolism was not derivative of French or Belgian models. It was infused with Baltic mythology, Lithuanian folklore, and a profound reverence for nature. In works like the “Sonata of the Sun”, “Fairy Tale of the Kings”, and “Creation of the World”, we encounter a vision of the universe suffused with light, energy, and mystical geometry. Spiraling suns, ascending staircases, and floating cities reflect an internal cosmos as much as an external one.

His use of color and form was also highly distinctive. Soft gradients, interwoven linework, and delicate layering created a dreamlike texture unlike anything in Lithuanian art before or since. Čiurlionis often painted in series—developing themes across multiple canvases, the way a composer explores motifs in a symphony.

Music as Method, Not Metaphor

What truly set Čiurlionis apart was his integration of musical structure into visual art. He was not simply illustrating sound or painting while listening to music—he was composing in paint. Many of his most celebrated series are organized as musical forms: the “Sonatas” series includes movements labeled “Allegro,” “Andante,” and “Finale.” The paintings progress thematically and tonally, just like a piece of music.

He described painting as a silent symphony. For him, every line had a tone, every hue a note. He wrote in his letters of hearing colors and seeing sound—a form of synesthesia that some scholars believe he may have literally experienced. But even if metaphorical, his approach changed how Lithuanian artists conceived of visual form—not as static image, but as temporal experience.

Myth, Cosmos, and National Identity

While Čiurlionis’s work is often cosmic and abstract, it is deeply rooted in Lithuanian myth and landscape. Mountains, forests, rivers, and skies recur throughout his paintings—not as real places, but as archetypal spaces. His imagery of kings, castles, and spirits draws from folk tales and oral tradition, reimagined through a Symbolist lens.

In this way, his art was both timeless and timely. As Lithuania struggled under Russian domination, Čiurlionis offered an artistic vision that was profoundly national without being overtly political. He created a mythic Lithuania—an inner homeland that could not be occupied or erased.

This aspect of his legacy became even more powerful after his death in 1911, when the movement for independence gained strength. Čiurlionis was canonized by Lithuanian intellectuals as a prophetic figure, a symbol of spiritual resistance and cultural depth.

The Circle of Čiurlionis and the Rise of Modernism

During his lifetime, Čiurlionis was a central figure in a growing network of Lithuanian artists, writers, and thinkers who sought to forge a modern national culture. He co-founded the Lithuanian Art Society in 1907 and exhibited in Vilnius and Warsaw. His presence helped galvanize the Lithuanian intelligentsia, inspiring younger artists to pursue new forms, themes, and media.

Painters like Antanas Žmuidzinavičius and Adomas Varnas, though more realist in style, were influenced by Čiurlionis’s commitment to national themes and emotional expressivity. Meanwhile, poets and composers saw in his work a model of interdisciplinary fusion—a way to blend high modernism with vernacular roots.

A Life Cut Short, A Legacy That Endured

Čiurlionis’s life was tragically brief. Struggling with mental health, overwork, and financial strain, he died in 1911 at a sanatorium near Warsaw at the age of 35. Yet the body of work he left behind—approximately 200 paintings, 300 musical compositions, and numerous writings—remains a cornerstone of Lithuanian cultural identity.

In the century since his death, Čiurlionis has been honored with museums, films, exhibitions, and scholarly studies. The M.K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum in Kaunas houses the largest collection of his works and serves as a pilgrimage site for admirers of his visionary art. His compositions are still performed internationally, and his paintings continue to influence artists exploring the intersection of spirituality and abstraction.

Perhaps most remarkably, his visual language has entered the Lithuanian national subconscious. His sun motifs, swirling forms, and ethereal landscapes recur not only in high art, but in design, illustration, animation, and even national branding.

Čiurlionis in the Broader Symbolist Context

While often considered a regional phenomenon, Čiurlionis belongs firmly within the European Symbolist tradition—alongside artists like Odilon Redon, Gustav Klimt, and Arnold Böcklin. Yet he differs from them in one key respect: his work is not decadent or urban, but cosmic and rooted. Where French Symbolists often explored psychological decay or eroticism, Čiurlionis turned toward harmony, transcendence, and unity.

His nearest aesthetic kin may actually be Wassily Kandinsky, who also explored the spiritual in art and claimed synesthetic experiences. Yet Čiurlionis preceded Kandinsky in many experiments with abstraction, leading some to consider him an unsung pioneer of abstract art.

Independence and Interwar Modernism (1918–1940)

The reestablishment of the Lithuanian state in 1918, following the collapse of the Russian Empire and the end of World War I, marked not only a political revolution but a cultural one. For the first time in centuries, Lithuanian artists were free to define their aesthetic on their own terms, unburdened by imperial censorship or forced assimilation. This brief but formative interwar period saw the rise of national institutions, international exchange, and a modernist visual culture that fused local tradition with avant-garde experimentation.

Between 1918 and 1940, Lithuania underwent a rapid transformation. Vilnius—though controversially annexed by Poland in 1920—remained a cultural flashpoint, while Kaunas, declared the temporary capital, blossomed into a vibrant modernist city. Artists, architects, designers, and educators came together to ask a central question: what should Lithuanian art look like in the modern world?

Cultural Infrastructure in the New Republic

One of the most critical achievements of the interwar era was the creation of a robust cultural infrastructure. The Kaunas Art School, founded in 1922, became the hub of Lithuanian art education, attracting leading figures such as Justinas Vienožinskis, Adomas Galdikas, and Petras Kalpokas as teachers. It trained a generation of painters, sculptors, and designers who would define the era’s aesthetic.

Art societies flourished, such as the Lithuanian Artists’ Association, founded in 1935. Exhibitions, journals, and critical discourse flourished in tandem. Art was no longer simply the preserve of the elite—it became a public project, part of building a new national consciousness.

Museums also gained prominence, especially the M.K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, which curated the emerging canon of Lithuanian art while honoring its visionary namesake. The preservation of folk art became an institutional priority as well, seen not as a relic of the past but as a wellspring for modern creativity.

Painting: Modernism with Roots

The dominant tension in interwar Lithuanian painting was between national realism and modernist stylization. On one side were artists like Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, whose landscapes and portraits emphasized clarity, harmony, and a connection to the Lithuanian land and people. On the other were younger, more experimental artists who embraced expressionism, abstraction, and symbolism.

Justinas Vienožinskis, for example, painted rural scenes that were simultaneously intimate and stylized—simplified forms, bold colors, and a decorative sensibility. He was particularly interested in the figure of the Lithuanian woman, often portraying her as both a symbol of cultural continuity and a modern subject. Vienožinskis’s work exemplifies what could be called “rooted modernism”—firmly tied to local themes but expressed in an international visual language.

Meanwhile, Adomas Galdikas brought a more overtly modernist aesthetic to Lithuanian art. His work ranged from highly structured landscapes to near-abstraction, using flattened planes and striking color harmonies. Galdikas also worked extensively in book illustration and stage design, helping define the broader visual language of the interwar period.

Another figure of note is Petras Kalpokas, whose landscapes and figural works struck a balance between lyricism and structure. His early Impressionist leanings gave way to a more sculptural realism in the 1930s, reflecting the era’s growing interest in monumentality and public representation.

Printmaking, Illustration, and Graphic Design

The interwar period was a golden age for Lithuanian printmaking and graphic arts. Artists such as Vytautas Kairiūkštis and Viktoras Petravičius explored the medium’s potential for both personal expression and mass communication. Woodcuts and etchings were especially popular, valued for their blend of folk aesthetic and expressive line.

Illustrated books, especially those for children, became a crucial site of artistic innovation. Publishers encouraged collaborations between writers and artists to produce modern Lithuanian fairy tales, historical narratives, and educational works with a distinctly national character. These books often drew on folk motifs, stylized typography, and bold compositions.

Lithuanian poster art also flourished, particularly in Kaunas, which was rapidly modernizing. Public health campaigns, cultural festivals, and political events were promoted through vivid posters that balanced functional clarity with decorative flair.

Architecture and Urban Modernism in Kaunas

Perhaps the most visible legacy of interwar Lithuanian art is found in architecture—especially in Kaunas, where the government, private developers, and artists collaborated to create a truly modern city. Functionalism and Bauhaus-inspired modernism took root, resulting in clean-lined buildings, rationalist planning, and minimalist ornamentation.

The Central Post Office, War Museum, and numerous residential buildings display a local take on International Style—emphasizing proportion, material honesty, and light. This architectural modernism was not purely aesthetic; it was ideological. Lithuania sought to present itself as a progressive, forward-looking republic, and the built environment became part of that narrative.

Interior design and applied arts were integrated into this vision. Furniture, lighting, ceramics, and textiles were created with a synthesis of modern form and folk motifs. The Kaunas School of Decorative Arts, established in 1930, trained designers to work across disciplines and bridge tradition with innovation.

Sculpture and National Memory

Sculpture in the interwar years played a pivotal role in shaping public memory. Monuments to national heroes, such as Vytautas the Great, King Mindaugas, and the Unknown Soldier, sprang up across Lithuania, often in prominent public spaces. These works balanced neoclassical gravitas with expressive individuality.

Sculptors like Juozas Zikaras—best known for designing Lithuania’s national symbol, the Vytis (Pahonia)—epitomized the fusion of art and nationalism. Zikaras’s sculptures, medals, and civic statuary often depicted idealized peasants, soldiers, and allegorical figures representing freedom, strength, and unity.

This turn toward monumental realism reflected the anxieties and aspirations of a young nation. As authoritarian currents grew stronger in the 1930s under President Antanas Smetona, art began to echo the aesthetics of statecraft—less experimental, more formal, and explicitly patriotic.

Women Artists and Modernity

The interwar period also saw the emergence of notable women artists, many of whom trained at the Kaunas Art School and abroad. Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, Elena Janulaitienė, and Kaja Sėliunaitė were among those exploring portraiture, still life, and symbolic abstraction.

Women’s increased visibility in the art world mirrored broader societal changes. As Lithuania modernized, the role of women in cultural and intellectual life expanded—though challenges remained. Many women artists balanced careers with teaching, publishing, and activism, and their work added new emotional registers to the national narrative.

Exhibitions, Internationalism, and Influence

Lithuanian artists were not isolated during this period. Exhibitions in Paris, Berlin, Riga, and Warsaw exposed them to international trends, and many studied abroad. The Lithuanian Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition showcased architecture, design, and folk art, signaling the republic’s modern cultural ambitions to the world.

Lithuania’s visual modernism shared affinities with Scandinavian design, Polish poster art, and Central European painting, yet remained grounded in its own motifs. It was this balance—between universal form and national content—that defined the era’s most enduring achievements.

The Curtain Falls: Occupation and Disruption

In 1940, Soviet forces occupied Lithuania, abruptly ending the interwar republic’s cultural flowering. Many artists fled, were imprisoned, or were co-opted by the regime. The institutions built over two decades were dismantled, and art would soon be forced into the ideological framework of socialist realism.

Yet the work of the interwar period lived on. It became a golden standard—invoked during the postwar diaspora, cited in underground art during Soviet repression, and revived in the post-1990 independence movement.

Art During Occupation: Soviet and National Socialist Censorship (1940–1990)

The 20th century dealt Lithuania a brutal succession of occupations—first by the Soviet Union in 1940, then National Socialist Germany in 1941, and again the Soviets from 1944 until the collapse of the USSR. Each regime imposed its own ideology, aesthetics, and limits, but all shared a fundamental suspicion of independent artistic expression. For Lithuanian artists, this was not simply a time of stylistic constraint—it was an existential crisis. Art became an arena of survival, protest, and coded defiance.

And yet, amid censorship, terror, and exile, Lithuanian art did not vanish. It mutated, went underground, wore masks. Some artists collaborated, many compromised, and others pushed the limits of what was possible. What emerged over these decades was not a single aesthetic, but a fragmented, paradoxical story of resistance and repression, where beauty and fear often shared the same canvas.

First Soviet Occupation (1940–1941): The Cultural Guillotine Falls

When the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania in June 1940, its first move was to dismantle the cultural institutions of the independent republic. Museums were “reorganized,” art schools purged, and major figures such as sculptor Juozas Zikaras lost their positions—or their lives. Zikaras himself, despondent over Soviet threats, took his own life in 1944.

The new regime replaced modernist experimentation and national symbolism with the aesthetics of Socialist Realism—a style mandated across the USSR that portrayed life as it should be under communism: heroic workers, joyful farmers, and glowing depictions of Lenin and Stalin.

Lithuanian artists were expected to align themselves with these ideals. Easels, styles, and subjects were prescribed. The result was a wave of visually competent but spiritually hollow work, often created under pressure or duress. Yet even in these earliest days, subtle resistance brewed: artists might depict idealized peasants with distinctly Lithuanian features, or sneak folk motifs into murals commissioned by the state.

National Socialist Occupation (1941–1944): Ethnic Terror and Cultural Displacement

The National Socialist invasion brought a temporary reprieve from Soviet mandates, but it was replaced by an even more brutal reality. The Holocaust annihilated Lithuania’s vibrant Jewish community—long one of the most artistically active in the region. Jewish painters, writers, and musicians were murdered, their studios and archives destroyed. The ghettoes, particularly in Vilnius and Kaunas, did preserve some artistic life—resistance art, secret performances, sketches—but little survived the genocide.

Meanwhile, Lithuanian artists found themselves in a precarious position. Some continued to work under German censorship, focusing on landscape, portraiture, or apolitical themes. Others engaged in underground publishing, illustrating banned materials or drawing anti-National Socialist cartoons for resistance groups. Art became a form of mourning and moral defiance.

The National Socialists promoted their own version of national art—stripped of modernist influence, classical in tone, and politically loyal. But the aesthetic demands were less rigid than those of the Soviets, allowing some space for personal expression. Still, it was an era of trauma, flight, and artistic fragmentation.

The Second Soviet Occupation (1944–1990): The Long Freeze and Slow Thaw

The return of Soviet control in 1944 marked the beginning of a 46-year occupation. In the immediate postwar years, Lithuania was subjected to intense Stalinist repression. Thousands were deported to Siberia, including artists and intellectuals. Art schools were purged again, and exhibitions tightly controlled.

From the 1940s through the early 1950s, Socialist Realism was the only sanctioned style. Paintings of factory workers, heroic partisans, and idealized youth adorned state buildings and propaganda posters. Lithuanians were required to depict the joy of Soviet life—even as they endured repression and loss.

However, in private, artists painted what they knew: landscapes of the Lithuanian countryside, rural interiors, portraits of melancholy rather than triumph. These works walked a dangerous line—subtly defiant, deeply human, and coded in national sentiment.

The “Sixties Generation” and the Return of the Personal

After Stalin’s death in 1953, a slow cultural thaw began. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, a new generation of Lithuanian artists emerged—trained within the system but pushing gently against its boundaries. This “Sixties Generation” produced work that was more introspective, symbolic, and formally innovative.

Figures such as Algirdas Steponavičius, Augustinas Savickas, and Vytautas Kasiulis began to explore expressionism, symbolism, and lyrical abstraction, often cloaked in themes that were formally acceptable but personally charged. Kasiulis, who had emigrated to the West after the war, gained international fame for his dreamlike interiors and melancholy figures—his success inspiring underground admiration in occupied Lithuania.

Many of these artists worked across media: easel painting, graphic arts, book illustration, and textile design. The applied arts, especially textiles and ceramics, became relatively safe spaces for stylistic exploration. Artists like Sofija Veiverytė and Kazys Šimonis worked with decorative abstraction that skirted the edges of official tolerance.

Book illustration in particular became a site of creative freedom. Illustrated folklore collections, children’s books, and poetry volumes often featured rich visual symbolism—camouflaged within the genre’s perceived innocence. The Lithuanian School of Book Illustration, which flourished from the 1960s onward, remains one of the most significant achievements of the Soviet period.

Nonconformists and Underground Art

From the 1970s onward, a growing number of Lithuanian artists began to operate outside official structures, creating work that directly challenged Soviet dogma. Though risky, these underground artists—many associated with the “Unofficial Art” movement—held secret exhibitions in apartments, churches, or rural barns.

One of the most iconic figures from this era is Vitalijus Stančikas, whose installations and performances blurred the line between art and activism. Others worked in video, conceptual art, and assemblage—mediums that were difficult to monitor and harder to censor. These artists forged a new kind of art: ephemeral, coded, and politically charged.

Visual symbolism often played a central role. The cross, the tree of life, the broken window—such motifs became talismans of resistance. Folk forms were revived not as nostalgia, but as quiet rebellion. Some even recreated traditional pagan rituals, connecting art to Lithuania’s pre-Christian heritage as a way to sidestep both Soviet materialism and Christian dogma.

Diaspora and Parallel Modernisms

While artists inside Lithuania faced restrictions, a thriving émigré art scene developed abroad. In cities like Chicago, Toronto, and New York, Lithuanian exiles exhibited freely, blending Baltic motifs with abstract expressionism, minimalism, and surrealism. Adolfas Valeška, Vytautas Kasiulis, and Rimtautas Gibavičius were among those whose work gained recognition in international circles.

These artists kept Lithuanian cultural memory alive abroad, often returning to folk symbols, national colors, and religious themes. Their exhibitions served as cultural diplomacy—reminding the world of a country erased from the map, but not from history.

Exile also freed artists to be overtly political. Posters, illustrations, and protest art produced in the diaspora often addressed Soviet oppression directly, creating a visual counterpoint to the muted symbolism of those still inside occupied Lithuania.

Late Soviet Period and Glasnost: Cracks in the Wall

By the 1980s, under Perestroika and Glasnost, artistic censorship began to weaken. Artists were allowed to travel more freely, exhibit abroad, and explore previously taboo subjects—religion, nationalism, historical trauma. New journals and exhibition spaces opened, and a generation of younger artists began to revisit topics like the Holocaust, the deportations, and the struggles of 1940s partisans.

The Sąjūdis Movement, which began in the late 1980s, galvanized artists and intellectuals. Art became a frontline of protest once again. Posters, performances, and public installations emerged with open political intent. The visual language of resistance—long encoded in metaphor—became explicit.

When Lithuania declared independence in 1990, artists were among the first to step into the daylight. Their work had laid the emotional and symbolic groundwork for liberation. Decades of silent resistance were finally given voice.

The Lithuanian Émigré Art Scene

While Soviet Lithuania existed under censorship and ideological scrutiny, a vibrant and often radical émigré art scene took shape in the diaspora. Scattered across Europe and North America, Lithuanian artists in exile created a cultural counter-narrative: one that affirmed national identity, embraced modernist experimentation, and documented both trauma and resilience. Far from being a marginal footnote, the art of the Lithuanian diaspora was a powerful creative force that helped preserve the country’s visual heritage and project it into global conversations.

These artists lived between worlds—geographically displaced but spiritually tethered to their homeland. Their work often wrestled with memory, exile, displacement, and cultural continuity. At the same time, freed from Soviet constraints, they engaged directly with contemporary movements in global art: abstraction, expressionism, surrealism, conceptualism, and beyond.

Waves of Displacement: Artists in Exile

The Lithuanian diaspora emerged in multiple waves. The first significant wave came during and after World War II, as artists, intellectuals, and civilians fled westward to escape Soviet reoccupation. Many passed through Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Germany before settling in countries like the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

A second, quieter wave occurred throughout the Cold War, as occasional emigrations, defections, or post-war resettlements brought new talent abroad. These émigré communities built their own institutions: art schools, galleries, publishing houses, and cultural festivals that helped maintain a distinct Lithuanian identity in foreign lands.

Adolfas Valeška: The Sacred and the Abstract

One of the most influential figures in the émigré scene was Adolfas Valeška (1905–1994), a painter, stained-glass artist, and stage designer who settled in Chicago. A former director of the Vilnius Art Museum and scenographer for the Lithuanian National Opera, Valeška carried his talents across borders, producing monumental stained-glass windows for churches and civic buildings in the United States.

Valeška’s visual language combined sacred themes, folk motifs, and abstraction. His stained-glass work, in particular, was striking for its rhythmic patterns and stylized religious iconography—bridging medieval Christian tradition with modernist geometry. Through his designs for Lithuanian churches abroad, Valeška helped turn exile spaces into sanctuaries of cultural continuity.

Vytautas Kasiulis: The Poetics of Displacement

Another towering figure was Vytautas Kasiulis (1918–1995), who fled to Germany during World War II and eventually settled in Paris. Unlike many of his compatriots, Kasiulis achieved significant international recognition, exhibiting throughout Europe and building a successful career in France.

His paintings are atmospheric, intimate, and suffused with melancholy elegance. Figures drift in softly rendered interiors; women in quiet contemplation, musicians, still lifes. His palette—muted earth tones and glowing pastels—suggests both nostalgia and dream. Kasiulis’s work avoids overt politics, but his themes of silence, detachment, and refined sadness speak powerfully to the émigré condition. The Vytautas Kasiulis Art Museum, established in Vilnius in 2013, has helped reconnect his legacy to contemporary Lithuanian audiences.

Chicago: A Lithuanian Cultural Capital in Exile

In the United States, Chicago emerged as the beating heart of Lithuanian émigré art. Home to thousands of Lithuanian immigrants, it fostered an unparalleled ecosystem of cultural activity. Institutions such as the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture and the Lithuanian Art Gallery served as exhibition spaces, archives, and social hubs.

Artists like Rimtautas Gibavičius, Algirdas Petrulis, and Algimantas Kezys (a priest and photographer) were central figures in this community. Kezys in particular made major contributions to Lithuanian-American visual culture, organizing exhibitions, promoting photography, and building bridges between generations of artists.

The Chicago Lithuanian Art scene was fiercely independent. Artists resisted assimilation by emphasizing national themes while engaging with contemporary techniques. At the same time, they contributed to broader American art through education, interdisciplinary collaborations, and participation in civic design.

Canada, Australia, and Beyond: Transnational Currents

The Lithuanian diaspora also flourished in Canada, particularly in Toronto and Montreal, where artists such as Kazys Varnelis and Birutė Žilytė developed personal idioms grounded in abstraction and narrative.

Varnelis, who taught at Columbia University and exhibited widely in the U.S. and Europe, is especially notable for his geometric abstraction and architectural minimalism. His work, influenced by Bauhaus and American modernism, seemed to eschew overt nationalism—yet his conceptual rigor and philosophical depth were deeply shaped by the discipline of cultural exile. In Vilnius, the Varnelis House-Museum (his final residence and collection) offers a glimpse into a mind shaped equally by Lithuanian tradition and American innovation.

In Australia, Lithuanian communities in Melbourne and Sydney produced artists whose works melded indigenous influence, abstract color fields, and memories of Baltic landscapes. Exhibitions often included both first- and second-generation artists, continuing a lineage of cultural memory through new stylistic frameworks.

Themes of Memory, Myth, and Nation

While stylistic diversity characterized the émigré scene, certain recurring themes tied it together:

- Exile and Displacement: Many artists expressed the psychological toll of exile through melancholic palettes, solitary figures, or fragmented forms.

- Memory and Myth: Folk symbols, pagan archetypes, and childhood memories populated the visual world of émigré artists. The tree of life, the sun motif, and rural architectural forms returned again and again.

- Religious Iconography: For many, Catholic imagery served not only spiritual needs but also as a cultural anchor. Churches commissioned émigré artists for stained glass, murals, and sculptures, turning sacred spaces into ethnic landmarks.

- National Identity: Even abstract or internationalist artists often titled their works with references to Lithuania—”Homeland,” “Baltic Elegy,” or “Druskininkai.” These gestures affirmed that artistic modernity and national longing were not mutually exclusive.

Émigré Journals, Exhibitions, and Legacy Building

Cultural journals played a vital role in disseminating art, theory, and criticism. Publications like Aidai, Metmenys, and Draugas regularly featured reproductions, essays, and reviews of Lithuanian artists abroad. In a pre-digital world, these journals were lifelines—connecting artists across oceans, generations, and artistic styles.

Exhibitions of émigré art were often organized around national anniversaries, independence commemorations, or international cultural showcases. While many occurred in church basements or community halls, others reached major institutions, including exhibitions at the United Nations, Smithsonian Institution, and various European galleries.

Artists also maintained deep relationships with Lithuania itself. Even during Soviet times, works were smuggled in or shown unofficially, and after 1990, many returned physically or symbolically. Retrospectives, museum acquisitions, and posthumous recognition have helped integrate these artists into the broader canon of Lithuanian art history.

Second-Generation Artists: Inheriting the Past, Inventing the Future

Many children of émigré artists became cultural figures in their own right—writers, visual artists, designers, and curators. Though born abroad, they inherited a powerful sense of Lithuanian identity and a complex relationship to both homeland and host country.

Some embraced hybrid forms—melding Baltic themes with pop art, feminist critique, or installation. Others consciously broke from their parents’ aesthetic, forging new global languages while quietly carrying ancestral memory.

This intergenerational dialogue continues today, particularly with renewed interest in diasporic identity in global art discourse. For Lithuania, it offers not only a reckoning with exile but a broader understanding of itself as a culture that lives across borders.

Independence and the Contemporary Art Explosion (Post-1990)

When Lithuania declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, the gates opened—not just politically, but artistically. After decades of censorship, forced ideology, and isolation, artists were free to explore, question, and create without state interference. What followed was a dramatic cultural unshackling: the birth of contemporary Lithuanian art as a force not only of national identity, but of global conversation.

The post-1990 era saw Lithuanian artists embrace conceptualism, performance, installation, digital media, and postcolonial critique. Art became not just a form of self-expression but a tool of memory work, activism, and international dialogue. Institutions reoriented themselves, new ones were built, and a generation of artists emerged who could finally speak—and be heard—in their own terms.

From Legacy to Liberation: The Early 1990s

In the immediate aftermath of independence, artists faced a paradoxical moment: unlimited freedom but little infrastructure. The Soviet system had provided studios, materials, and institutional pathways (albeit restricted ones); now, these supports were gone. But with that came exhilarating autonomy.

Former underground artists came to the forefront, and younger creators took bold steps into installation, video, and conceptual practices. Exhibitions became more daring. Performance art, once forced into semi-private spaces, moved into public squares, abandoned buildings, and even the streets.

A notable force during this period was the “Post Ars” group, a collective founded in the late 1980s that gained real momentum in the early ’90s. Members such as Gintaras Znamierowski, Saulius Valius, and Kazimieras Skučas created interdisciplinary installations that blurred the lines between sculpture, sound, and ritual. Their work responded to national trauma, ecological concerns, and post-Soviet disorientation with both poetic ambiguity and raw materiality.

The Lithuanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Perhaps the most visible symbol of Lithuania’s emergence on the international art stage has been its participation in the Venice Biennale, the world’s premier contemporary art exhibition. Since 1999, the Lithuanian Pavilion has consistently drawn attention for its conceptual rigor and formal innovation.

A landmark moment came in 2019, when Lithuania won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation with Sun & Sea (Marina), a site-specific opera-performance created by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė (director), Vaiva Grainytė (librettist), and Lina Lapelytė (composer). Set on an artificial beach inside a pavilion, the performance featured lounging sunbathers singing about ecological collapse in a deadpan, operatic tone. At once seductive and devastating, the piece was a masterstroke of environmental and cultural critique—and a statement that Lithuania was now a major voice in global art.

Themes of Memory, Trauma, and Reclamation

Contemporary Lithuanian art is haunted by its past—not only the Soviet era, but the deeper layers of occupation, repression, and silence. Many artists engage in memory work, unpacking the unspoken traumas of deportation, the Holocaust, postwar guerrilla resistance, and cultural erasure.

Artists such as Deimantas Narkevičius have tackled these themes head-on. Narkevičius is one of Lithuania’s most internationally acclaimed artists, known for his video works and films that explore the failures of memory and the ruins of ideology. His 2001 piece Once in the XX Century reverses footage of a Lenin statue being torn down—turning it into a surreal moment of resurrection. The film asks: What do we really erase when we topple monuments?

Similarly, Artūras Raila has created installations and interventions that challenge national myths and explore marginality, spirituality, and authoritarian residues.

Meanwhile, Egle Rakauskaitė, working in video and performance, has explored bodily identity, gender, and historical amnesia through provocative, often visceral gestures—bathing in honey, smearing her body with clay, or using textiles and hair as media. Her work speaks to a feminist consciousness long suppressed in Lithuanian visual culture.

Vilnius: A Contemporary Art Capital

The capital city of Vilnius has become a thriving center for contemporary art. Key institutions such as the Contemporary Art Centre (CAC)—one of the largest venues for contemporary art in the Baltics—have hosted major international exhibitions and fostered experimental practices since the early 1990s.

The CAC’s flagship event, Baltic Triennial, is a vital platform for emerging voices across Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. These triennials engage with issues ranging from regional memory and identity to digital culture, climate change, and post-Soviet aesthetics.

Independent spaces like Rupert, an interdisciplinary art residency and education center, and Vartai Gallery, one of Lithuania’s most prominent commercial galleries, have also propelled contemporary artists onto the global scene.

Digital Art, AI, and the Global Present

Like much of the world, Lithuania’s contemporary scene has embraced digital media, AR/VR, and AI-generated work. Artists are exploring surveillance, data, memory, and the limits of authorship. New media artists such as Tautvydas Bajarkevičius and Ieva Baltmiškytė are using code, projection, and online platforms to critique capitalism, climate collapse, and the aesthetics of control.

Digital residencies, NFT exhibitions, and online curatorial platforms emerged especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, giving Lithuanian artists wider visibility and alternative modes of circulation.

Yet despite this embrace of the global, there remains a profound sense of rootedness—a desire to hold onto the landscape, language, and ritual patterns that have defined Lithuanian culture for centuries.

Art After War: Ukraine, Russia, and Regional Solidarity

Since the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Lithuanian artists have taken on new political urgency. Exhibitions, fundraisers, and collaborations with Ukrainian artists have exploded, with many creatives using their work to process solidarity, trauma, and the shared legacy of imperial violence.

Art in Lithuania has re-entered the political square—murals, posters, and performance actions in Vilnius and Kaunas speak to this moment with clarity and passion. This marks a return to the fusion of art and activism seen during the Sąjūdis movement, but now transnational in its reach.

Institutions and Infrastructure: Museums, Academies, and Biennales

Art is not just made—it is taught, exhibited, conserved, critiqued, and circulated. In Lithuania, the institutions that have nurtured artistic production—from the grand halls of national museums to the experimental spaces of artist-run initiatives—have played a crucial role in constructing the nation’s visual culture. These institutions do more than hold artworks; they curate narratives, foster new voices, and serve as sites of both memory and reinvention.

Lithuania’s cultural infrastructure is especially dynamic given its historical ruptures: imperial occupation, interwar independence, Soviet repression, and post-1990 rebirth. Each phase left behind institutions—some inherited, others dismantled, many transformed. What we see today is a layered and ambitious ecosystem that spans classical collections, cutting-edge media art, and decentralized community-based programming.

Museums as Memory Keepers and Storytellers

Lithuania’s major museums are not only repositories of visual culture—they are guardians of national identity. These institutions have preserved, curated, and reinterpreted centuries of artwork, offering narratives that bridge folk heritage, statehood, trauma, and modernity.

At the forefront is the M.K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art in Kaunas, founded in 1921 and named after Lithuania’s visionary symbolist painter and composer. The museum holds an extensive collection of Čiurlionis’s works alongside folk art, interwar modernism, and Soviet-era painting. It plays a dual role as both sanctuary and laboratory—a place of reverence for national icons and a site for rethinking historical continuity.

Another pillar is the Lithuanian Art Museum (Lietuvos dailės muziejus) in Vilnius, an umbrella institution with multiple branches:

- The National Gallery of Art (Nacionalinė dailės galerija) offers a modernist and contemporary lens, showcasing Lithuanian art from the 20th century to the present. Its clean, minimalist spaces provide a striking contrast to the ornate canvases and ideological burdens they often contain.

- The Radvila Palace Museum of Art focuses on older European and Lithuanian works, including Baroque and Renaissance pieces.

- The Applied Arts and Design Museum, also under the umbrella, preserves craft traditions while curating new design movements.