Japan’s art history is one of the richest and most enduring in the world, reflecting a deep connection to nature, spirituality, and craftsmanship. Rooted in traditions dating back thousands of years, Japanese art has evolved through the influence of Buddhism, Shintoism, and external cultural exchanges. From the cord-marked pottery of the Jōmon period to the vibrant woodblock prints of Edo, each era has contributed distinct techniques and styles. This progression reveals a culture deeply invested in balance, harmony, and the celebration of both the ephemeral and eternal.

A defining characteristic of Japanese art is its seamless integration of functional design and aesthetic beauty. Everyday objects, from ceramics to textiles, are often treated as art forms, embodying the philosophy that beauty should enrich all aspects of life. This principle, deeply influenced by Zen Buddhism and Shintoism, values simplicity, imperfection, and the natural flow of materials. Such ideals have made Japanese art both timeless and universally admired.

Throughout its history, Japan has shown an unparalleled ability to adapt and innovate while preserving its traditions. For example, during periods of isolation, Japanese art flourished independently, developing unique styles such as ukiyo-e. Conversely, in eras of openness, such as the Meiji Restoration, Japan embraced foreign influences, blending them seamlessly with its own aesthetics. This duality has enabled Japanese art to remain relevant and influential across centuries.

Today, Japan continues to be a global leader in art, design, and architecture, captivating audiences with its traditional crafts and cutting-edge innovations. Contemporary artists like Yayoi Kusama and creative collectives like teamLab embody the spirit of blending old and new. Meanwhile, Japan’s pop culture—dominated by manga, anime, and video games—has introduced its visual language to millions worldwide. The enduring legacy of Japanese art lies in its ability to transcend borders, connecting people to the essence of beauty and creativity.

Section 1: Prehistoric Japanese Art (Jōmon to Yayoi Periods)

The Jōmon period (10,500 BCE–300 BCE) is considered the starting point of Japanese art, characterized by its distinctive pottery. The word “Jōmon” translates to “cord-marked,” referring to the patterns impressed into clay pots using twisted cords. These pots were not just utilitarian; they were often highly decorative, showcasing early humans’ appreciation for beauty in everyday objects. The intricate designs of Jōmon pottery are among the oldest known ceramic works in the world, demonstrating the advanced artistic capabilities of this prehistoric culture.

Jōmon art extended beyond pottery to include figurines known as dogū, which are small clay sculptures often resembling human or animal forms. These figurines are believed to have had spiritual or ritualistic purposes, possibly serving as talismans for fertility or protection. Dogū often feature exaggerated features, such as large eyes or limbs, lending them a mysterious and otherworldly quality. These sculptures provide insight into the spiritual beliefs and symbolic expression of Japan’s earliest inhabitants.

The Yayoi period (300 BCE–300 CE) followed the Jōmon and marked significant shifts in Japanese art and society, as agriculture and metalworking were introduced. Pottery became simpler and more functional, reflecting the more structured and agricultural way of life. The Yayoi people also created dōtaku, bronze ceremonial bells adorned with intricate patterns depicting scenes of nature, animals, and human activities. These bells were likely used in religious ceremonies, symbolizing a connection between art and ritual.

Together, the Jōmon and Yayoi periods laid the foundation for Japan’s enduring relationship between art, spirituality, and practicality. Jōmon art emphasized decorative beauty, while Yayoi art reflected functionality and emerging social structures. Despite their differences, both periods demonstrated the early Japanese ability to integrate creativity with daily life. These artistic traditions set the stage for later periods, where similar themes of simplicity, symbolism, and nature would continue to resonate throughout Japanese art history.

Section 2: Kofun and Asuka Periods (300–710 CE)

The Kofun period (300–538 CE) derives its name from the large burial mounds, or kofun, built to honor the elite and rulers of early Japan. These tombs were often surrounded by haniwa, terracotta clay figures depicting warriors, animals, houses, and other symbolic forms. The haniwa were believed to protect the deceased in the afterlife, serving both decorative and spiritual purposes. These sculptures demonstrate the sophisticated craftsmanship and the emerging social stratification of the period.

Kofun tombs also reveal a growing influence of Chinese and Korean art and culture, particularly in metallurgy and architecture. The introduction of iron tools and weapons allowed for more advanced construction techniques and detailed designs. This period also saw the development of early forms of Shinto-inspired art, such as mirrors and jewelry buried alongside the deceased. These objects reflect a spiritual connection to nature and ancestral worship, central to early Japanese beliefs.

The Asuka period (538–710 CE) was transformative, as the introduction of Buddhism from Korea profoundly influenced Japanese art and architecture. Buddhist sculptures became prominent, often crafted in bronze and stone, depicting serene Buddhas and bodhisattvas. The Hōryū-ji Temple, built in the early 7th century, is a prime example of Asuka architecture and is one of the oldest wooden structures in the world. Its five-story pagoda and golden hall reflect the adoption and adaptation of Chinese and Korean Buddhist designs to Japanese sensibilities.

The Asuka period also marked the beginning of written records, which allowed for greater cultural exchange and documentation of artistic achievements. Paintings on temple walls, such as the Takamatsuzuka tomb murals, displayed colorful depictions of celestial beings and scenes from Buddhist mythology. These advancements laid the groundwork for Japan’s classical art traditions, blending indigenous practices with imported ideas. The innovations of the Kofun and Asuka periods would deeply influence the development of Japan’s cultural identity for centuries to come.

Section 3: Classical Japanese Art (Nara and Heian Periods, 710–1185 CE)

The Nara period (710–794 CE) marked the first centralized government in Japan, with the city of Nara as its capital. During this time, Buddhist art and architecture flourished, heavily influenced by Chinese Tang Dynasty aesthetics. The most iconic example of this era is the Great Buddha of Tōdai-ji, a massive bronze statue housed in the world’s largest wooden building. Nara’s art emphasized grandeur and devotion, reflecting the importance of Buddhism in unifying and legitimizing the ruling class.

In addition to large-scale architecture, Nara artists excelled in producing intricate Buddhist sculptures and paintings. Temples like Hōryū-ji and Yakushi-ji housed collections of statues depicting deities, bodhisattvas, and guardians, often rendered with serene expressions and elegant postures. The Shōsōin, the imperial treasury in Nara, preserved artifacts such as textiles, lacquerware, and musical instruments, showcasing the period’s sophisticated craftsmanship. These works demonstrated a seamless blend of religious devotion and artistic innovation.

The Heian period (794–1185 CE) saw the rise of a distinctly Japanese style of art, as cultural exchange with China diminished. Yamato-e painting emerged, characterized by vibrant colors and narrative scenes from Japanese literature, history, and folklore. Scrolls like the Tale of Genji Emaki illustrate episodes from the world’s first novel, The Tale of Genji, using intricate details and emotional depth. These works emphasized refined aesthetics and storytelling, reflecting the tastes of the aristocracy.

Calligraphy and poetry also flourished during the Heian period, with the kana writing system enabling uniquely Japanese expressions. Women of the imperial court, such as Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shōnagon, contributed to literary and artistic traditions that emphasized elegance and sensitivity. Architecture, like the Phoenix Hall at Byōdō-in, reflected an appreciation for natural harmony, with its symmetrical design and integration into the surrounding landscape. The classical art of the Nara and Heian periods established foundational themes of spirituality, refinement, and connection to nature that continue to define Japanese aesthetics.

Section 4: Medieval Japanese Art (Kamakura and Muromachi Periods, 1185–1573 CE)

The Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE) marked a turning point in Japanese art, reflecting the rise of the samurai class and the influence of Zen Buddhism. Art became more realistic and dynamic, as seen in the powerful Buddhist sculptures of Unkei and Kaikei, whose works conveyed human emotion and spiritual strength. Iconic pieces like the statue of Kongō Rikishi at Tōdai-ji showcase intricate details and dramatic movement. These sculptures symbolized the warrior ethos of the era, blending spiritual devotion with physical vigor.

Painting during the Kamakura period reflected a similar focus on realism and narrative. Emaki-mono, or illustrated scrolls, flourished, depicting historical and legendary events in vivid detail. The Heiji Monogatari Emaki, for example, chronicles dramatic episodes from the Heiji Rebellion, showcasing action-packed battle scenes. Zen Buddhist ink paintings, known as sumi-e, emerged, emphasizing simplicity and spiritual contemplation. These black-and-white works often depicted landscapes, reflecting the Zen ideals of impermanence and harmony with nature.

The Muromachi period (1336–1573 CE) continued the artistic traditions of the Kamakura period while embracing new forms of expression influenced by Zen Buddhism. Ink painting reached new heights with artists like Sesshū Tōyō, whose landscapes conveyed both technical mastery and profound spiritual depth. The kare-sansui (dry landscape) gardens of Zen temples, such as the one at Ryōan-ji, became iconic expressions of Muromachi aesthetics, symbolizing the universe through carefully arranged rocks and sand. These minimalist designs reflect the Zen principle of achieving enlightenment through simplicity.

The tea ceremony, or chanoyu, emerged as an important cultural practice during the Muromachi period, combining art, philosophy, and ritual. Tea masters like Murata Jukō introduced wabi-sabi aesthetics, emphasizing imperfection and the beauty of the natural world. This philosophy influenced the creation of tea bowls, utensils, and tea houses, which became integral parts of Japanese art. The Kamakura and Muromachi periods solidified themes of realism, spirituality, and simplicity, leaving a lasting legacy on Japanese aesthetics and culture.

Section 5: Edo Period and Ukiyo-e (1603–1868)

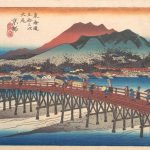

The Edo period (1603–1868) was a time of peace, economic prosperity, and cultural flourishing under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate. Art during this period became more accessible to the general population, with the rise of ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world,” a genre of woodblock prints that depicted urban life, landscapes, and kabuki actors. Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige became renowned for their intricate designs and vibrant colors. Ukiyo-e provided an escape from daily life, celebrating the fleeting pleasures and beauty of the Edo period.

Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, including the iconic The Great Wave off Kanagawa, exemplifies the ukiyo-e focus on nature and humanity’s relationship to it. His work combined traditional Japanese aesthetics with innovative perspectives, influencing artists worldwide. Similarly, Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō captured the beauty of Japan’s countryside and travel routes, immortalizing scenes of daily life and seasonal changes. These prints reflected the Edo-period fascination with nature, travel, and the joys of leisure.

Decorative arts also flourished during the Edo period, with advancements in ceramics, lacquerware, and textiles. Pottery styles like Imari and Kakiemon gained international acclaim for their intricate designs and vibrant glazes. Lacquerware items, including trays and boxes, featured elaborate inlays and gold embellishments, blending functionality with artistic elegance. Kimono production reached new heights, with intricate patterns and vibrant colors showcasing the artistic mastery of textile artisans. These crafts reflected the Edo-period emphasis on both beauty and utility.

The samurai class continued to influence art through the creation of ornate armor and weaponry, blending practicality with aesthetic sophistication. Swords and their fittings were treated as art forms, often featuring intricate carvings and inlays. Samurai culture also extended to Noh and kabuki theater, which became central to Edo-period entertainment. Kabuki’s elaborate costumes and dramatic performances mirrored the vibrant energy of ukiyo-e, while Noh retained its spiritual and minimalist roots. The Edo period laid the groundwork for many enduring Japanese art forms, reflecting a society that valued creativity, beauty, and cultural refinement.

Section 6: Meiji Restoration and Modernization (1868–1912)

The Meiji Restoration (1868–1912) marked a dramatic transformation in Japan’s political, social, and cultural landscape, as the country rapidly modernized and embraced Western influences. During this period, Japanese art underwent significant changes, blending traditional aesthetics with newly introduced techniques and ideas. The government actively promoted modernization through cultural diplomacy, exhibiting Japanese art and crafts at international expositions. This fusion of old and new helped Japan assert its identity on the global stage while redefining its artistic traditions.

Traditional art forms such as ukiyo-e adapted to the changing times, with artists incorporating Western techniques like perspective and shading. Yōga (Western-style painting) emerged, with artists like Kuroda Seiki adopting oil painting and academic realism. His works, such as Lakeside (1897), reflected Western artistic principles while retaining subtle Japanese sensibilities. At the same time, nihonga, or traditional Japanese painting, continued to flourish, blending elements of Western realism with classical Japanese themes and materials.

Architecture during the Meiji period also reflected the convergence of Western and Japanese influences. Iconic structures like the Rokumeikan, designed by Josiah Conder, showcased Western-style grandeur, serving as a symbol of Japan’s modernization. However, architects such as Tatsuno Kingo maintained a balance by incorporating Japanese aesthetics into modern designs, as seen in the Tokyo Station building. This period saw the emergence of new public spaces, such as museums, schools, and government offices, which became sites for showcasing both traditional and modern artistic achievements.

Craftsmanship and industrial arts experienced a renaissance during the Meiji era, as traditional artisans adapted their techniques to meet international demand. Pottery styles such as Satsuma and Kutani gained global recognition for their intricate designs and vivid colors. The production of lacquerware and cloisonné enamel also reached new heights, blending traditional motifs with modern techniques. The Meiji Restoration transformed Japanese art into a dynamic synthesis of tradition and innovation, setting the stage for the artistic experimentation of the 20th century.

Section 7: Taishō and Shōwa Periods (1912–1989)

The Taishō period (1912–1926) was marked by social liberalization and artistic experimentation, as Japan embraced modernism and avant-garde movements. Influenced by Western styles such as Art Deco and Cubism, artists sought to explore new forms of expression while retaining elements of traditional Japanese aesthetics. The Mingei Movement, led by Yanagi Sōetsu, celebrated the beauty of folk crafts, emphasizing simplicity and functionality. This period witnessed a dialogue between traditional craftsmanship and modernist innovation, reflecting a rapidly changing society.

During the early Shōwa period (1926–1945), Japan’s militarization and involvement in World War II greatly impacted its art and culture. Propaganda art became prominent, with posters, films, and illustrations promoting nationalist ideals and the war effort. However, some artists, such as members of the Gutai Art Association, resisted conformity by experimenting with abstract and avant-garde art forms. Despite government restrictions, works like these laid the groundwork for postwar artistic revival, emphasizing individual creativity and defiance of traditional norms.

The postwar Shōwa period (1945–1989) saw a remarkable resurgence in Japanese art, as the nation rebuilt itself after the devastation of World War II. Artists grappled with themes of loss, resilience, and identity, exploring new mediums and techniques. The Gutai Art Association, founded in 1954, became internationally renowned for its experimental approach, integrating performance, painting, and installation. Key works, such as Kazuo Shiraga’s dynamic action paintings, reflected the liberation of postwar creativity and Japan’s reentry into the global art scene.

By the late Shōwa period, Japan had established itself as a leader in modern art, design, and architecture. The rise of postmodernism inspired architects like Kenzo Tange, whose designs blended traditional Japanese elements with futuristic forms. In the visual arts, photographers such as Daido Moriyama captured the contrasts of urban life, while printmakers like Shikō Munakata celebrated folk traditions. The Taishō and Shōwa periods were pivotal in shaping modern Japanese art, balancing the tension between tradition and innovation while addressing the challenges of a rapidly changing world.

Section 8: Contemporary Japanese Art (1989–Present)

Contemporary Japanese art reflects a dynamic fusion of tradition, technology, and global influence, cementing Japan’s position as a leader in the global art scene. Since the Heisei period (1989–2019) and into the Reiwa period (2019–present), Japanese artists have pushed boundaries through innovative approaches in visual art, performance, and digital media. The works of Yayoi Kusama, with her polka-dot patterns and immersive installations like Infinity Mirrored Rooms, have gained global acclaim. Kusama’s art explores themes of infinity, mental health, and the human connection to the cosmos, making her a defining figure of contemporary art.

The integration of technology has been a hallmark of modern Japanese art, exemplified by collectives like teamLab, known for their interactive digital installations. Their works, such as Borderless in Tokyo, use projection mapping, motion sensors, and digital effects to create immersive experiences that blur the lines between art and viewer. Artists like Takashi Murakami have embraced pop culture through his Superflat movement, blending traditional Japanese art styles with manga, anime, and commercial aesthetics. Murakami’s iconic works, like his vibrant flower motifs and collaborations with global brands, exemplify Japan’s cultural versatility.

Japanese contemporary art is also deeply rooted in environmental and societal concerns. Artists such as Chiharu Shiota, known for her large-scale installations of thread and found objects, explore themes of memory, identity, and the human condition. Meanwhile, architect Kengo Kuma incorporates sustainable materials and designs that harmonize with natural landscapes, reflecting a growing global emphasis on environmental responsibility. These themes resonate across disciplines, from photography to sculpture, highlighting Japan’s cultural engagement with pressing modern issues.

Pop culture art, including manga, anime, and video game design, has played a significant role in Japan’s artistic identity in the modern era. Series like Akira and Spirited Away have transcended entertainment, becoming globally recognized works of art. Video games like The Legend of Zelda and Final Fantasy demonstrate how storytelling and visual design can elevate interactive media to high art. Contemporary Japanese art remains a vital force in global culture, blending tradition and innovation while addressing universal themes in a distinctly Japanese way.

Section 9: Japanese Architecture as a Parallel Tradition

Japanese architecture is a profound reflection of the country’s cultural identity, blending functionality, aesthetics, and harmony with nature. Rooted in ancient traditions, it emphasizes simplicity, natural materials, and spatial awareness, as seen in Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. Structures like the Ise Grand Shrine, rebuilt every 20 years, embody the Shinto values of renewal and impermanence. These architectural principles have influenced centuries of design, maintaining a balance between the spiritual and the practical.

During the Heian and Kamakura periods, Japanese architecture evolved to accommodate religious and social changes. Buddhist temples like Tōdai-ji in Nara and Byōdō-in’s Phoenix Hall in Uji display intricate wooden structures that harmonize with their natural surroundings. Zen Buddhism introduced kare-sansui (dry landscape gardens) as an extension of temple architecture, exemplified by the Ryōan-ji garden in Kyoto. These designs reflect a deep connection to meditation and the appreciation of minimalism, themes that remain central to Japanese architectural philosophy.

In the modern era, Japanese architects like Tadao Ando and Kenzo Tange have revolutionized global architecture by integrating traditional elements with contemporary techniques. Tange’s designs, such as the Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, combine modernist principles with Japanese spatial sensibilities. Ando’s works, like the Church of the Light, use concrete and natural light to create spaces that evoke tranquility and introspection. These architects demonstrate how Japan’s architectural heritage continues to inspire innovation while retaining its distinct character.

Contemporary architecture in Japan further emphasizes sustainability and adaptive reuse, as seen in the works of Kengo Kuma and Shigeru Ban. Kuma’s projects, like the Japan National Stadium, incorporate natural materials and blend seamlessly with their environments. Ban’s use of recyclable materials, such as paper and bamboo, highlights Japan’s growing focus on ecological responsibility. Japanese architecture serves as both a reflection of its cultural history and a forward-looking exploration of how design can address the needs of modern society while staying true to timeless principles.

Section 10: Conclusion—The Timeless Legacy of Japanese Art

Japanese art has long been a testament to the nation’s cultural resilience, adaptability, and commitment to aesthetic principles. From the intricate cord-marked pottery of the Jōmon period to the cutting-edge digital installations of teamLab, Japanese artists have continuously pushed the boundaries of creativity. This legacy reflects a profound ability to balance tradition with innovation, creating works that resonate across time and cultures. Japan’s art not only tells the story of its own evolution but also offers insights into universal human experiences.

The country’s connection to nature and spirituality has remained a constant thread in its artistic expression. Whether through the Zen-inspired dry gardens of the Muromachi period or the organic architecture of Tadao Ando, Japan’s art is deeply intertwined with its environment. This sensitivity to the ephemeral and the eternal has given Japanese art a timeless quality, making it as relevant today as it was centuries ago. Such harmony between tradition and modernity has allowed Japanese art to thrive in a rapidly changing world.

In contemporary times, Japan has become a global hub for creative innovation, influencing fields as diverse as pop culture, architecture, and environmental art. Figures like Yayoi Kusama and Takashi Murakami have brought Japanese aesthetics to the forefront of global conversations, while traditional crafts like ceramics and lacquerware continue to be celebrated worldwide. Japanese art’s ability to bridge cultural divides and inspire dialogue underscores its enduring impact on global culture.

As Japan moves further into the 21st century, its art continues to evolve, engaging with themes like technology, sustainability, and social responsibility. Yet, at its core, Japanese art remains a celebration of beauty, simplicity, and the profound connection between humanity and the natural world. This enduring legacy ensures that Japan will remain a beacon of creativity and inspiration for generations to come.