The Brittany School wasn’t a school in the traditional sense—it had no curriculum, no official building, and no formal instructors. Instead, it was a loosely connected group of artists who found themselves drawn to Brittany, a coastal region in northwestern France, during the second half of the 19th century. From the 1860s to the early 1900s, dozens of painters fled the growing industrialization and materialism of Paris, seeking a purer, more spiritual subject matter in Brittany’s rugged landscapes and devout Catholic communities. The Brittany School was born from this movement—not as an institution, but as a way of seeing the world.

What made Brittany special to these artists was its deep connection to tradition, myth, and nature. The area remained largely untouched by the modernizing hand of the French Republic, preserving a way of life that seemed increasingly rare elsewhere in Europe. Artists were drawn to the region’s religious festivals, peasant costumes, windswept cliffs, and fog-draped villages. Brittany provided them not only with subject matter but also a retreat—a quiet place to rethink their art away from the salons of Paris.

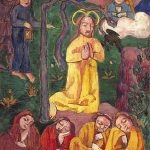

Though the Brittany School shared some stylistic connections with Impressionism, it quickly branched into more emotional and symbolic realms. Many of the artists rejected the fleeting light and quick brushwork of the Impressionists, instead embracing bold color blocks, strong outlines, and mystical subject matter. They were searching for more than surface beauty—they wanted meaning, and Brittany’s spiritual ambiance gave them just that.

The term “Brittany School” is used today by art historians to describe this wave of artists who worked in the region, especially around Pont-Aven and Le Pouldu. While not unified by a manifesto, they were bound by their shared admiration for Brittany’s culture and their rejection of modern urban life. It’s a fascinating moment in art history where tradition, rebellion, and spirituality collided to shape the future of modern art. While Pont-Aven was the best-known hub — largely due to Paul Gauguin — it represented only one part of a much larger artistic presence in Brittany. Many other painters, such as Alfred Guillou, Théophile Deyrolle, and Henri Barnoin, worked in Concarneau, Douarnenez, and Le Faouët. Their focus was realism, religious tradition, and everyday Breton life — very different from the Symbolist abstraction of the Pont-Aven group. These artists formed the core of what is broadly known as the Brittany School, independent of Gauguin’s stylistic rebellion.

Why Pont-Aven Became the Heart of the Movement

Pont-Aven, a quiet village nestled along the Aven River, became the beating heart of the Brittany School in the late 1800s. Its cobbled streets, gentle bridges, and mossy riverbanks formed a picturesque setting that artists found irresistible. By the 1860s, painters from Paris and beyond had begun visiting Pont-Aven to capture its unique light and rustic charm. But it wasn’t until the 1880s that the village blossomed into a vibrant artists’ colony.

One of the village’s biggest draws was the affordability and hospitality of local lodgings, particularly the famed Pension Gloanec. Here, painters could rent rooms cheaply and eat hearty meals at communal tables, sparking the kind of spontaneous conversations that fueled creative growth. The inn’s walls were plastered with paintings, and payments were often made in art rather than coin. This barter-based economy supported the artists while allowing them to form deep social and professional bonds.

Pont-Aven was also rich in the very things many painters had grown tired of searching for in the cities: authenticity, faith, and connection to the land. The town hosted religious processions, festivals, and ceremonies that became subject matter for many Brittany School works. The rhythms of daily life—harvesting fields, tending sheep, walking to mass—were far removed from the industrialized Parisian streets. Artists found solace in that slow, sacred pace.

The mix of French, American, British, and Scandinavian painters created an international atmosphere in the village. These artists weren’t simply copying the landscape—they were pushing boundaries and redefining what art could be. Pont-Aven became more than a destination; it was a creative crucible. What started as a trickle of curious painters grew into a cultural phenomenon that shaped the next century of visual art.

Paul Gauguin and the Rise of Synthetism

Paul Gauguin, born on June 7, 1848, in Paris, began life in a completely different world from the pastoral simplicity of Brittany. A former stockbroker and sailor, he turned to painting seriously in the 1870s, eventually abandoning his bourgeois life in pursuit of something deeper. By the time he arrived in Pont-Aven in 1886, he was searching for an escape from both Impressionism and civilization itself. Gauguin found that escape in Brittany’s medieval traditions and pious atmosphere.

His early time in Pont-Aven coincided with a key shift in his artistic style. Rejecting Impressionism’s focus on fleeting light, he developed Synthetism—a bold new visual language that blended the subject’s outer appearance with its inner meaning. This style used flat areas of color, dark contours, and abstracted shapes to express emotion and spiritual truth. By 1888, Gauguin had solidified his stylistic break from the Paris elite and was leading younger artists into this new vision of modern art.

During this pivotal time, Gauguin formed important partnerships, especially with Émile Bernard (born April 28, 1868). Bernard, only 20 years old when he met Gauguin, was already experimenting with a style known as Cloisonnism, inspired by stained glass and Japanese prints. The two artists pushed each other toward greater abstraction, developing a visual style that emphasized symbolic meaning over realistic representation. Their shared works from this period are among the most influential in modern art’s evolution.

Yet Gauguin was never content to stay in one place. After Brittany, he moved to Le Pouldu in 1889 and eventually left France entirely, traveling to Tahiti in 1891. There, he continued developing his symbolic style, but the seeds of it had been planted in Brittany. Gauguin died in the Marquesas Islands in 1903, but his impact on modern art—especially through his time in Pont-Aven—remains foundational. His rebellion against realism began in Brittany and shaped the artistic revolutions of the 20th century.

Key Figures of the Brittany School

While Gauguin is the most famous name associated with the Brittany School, many other artists played crucial roles in shaping its direction and style. One of the most important was Émile Bernard, who was born in Lille in 1868 and trained at the École des Beaux-Arts. Though younger than Gauguin, Bernard’s theoretical contributions were significant. His development of Cloisonnism—using thick outlines and flat color planes—directly influenced Gauguin and others.

Another key figure was Charles Laval, born in Paris in 1861. A close friend of Gauguin, Laval accompanied him on a famous 1887 trip to Martinique, producing works filled with tropical color and bold shapes. Though he worked side-by-side with Gauguin in Brittany as well, Laval’s name has often been overshadowed. Tragically, he died young—just 33 years old—in 1894 from tuberculosis, cutting short a promising career.

Paul Sérusier, born in 1864 in Paris, also deserves special mention. In 1888, he painted The Talisman under Gauguin’s direct guidance, a work that became a visual manifesto for the Nabis, an avant-garde group that followed. Sérusier’s work emphasized the spiritual and mystical aspects of Brittany’s culture, often focusing on peasant women, religious rites, and serene landscapes. His time in Brittany deeply influenced his later philosophy of art, which embraced abstraction and symbolism.

Other notable contributors included Maxime Maufra (born 1861), Armand Séguin (born 1869), and Henry Moret (born 1856), each bringing their own interpretations of Brittany’s rugged charm. Some artists, like Moret, leaned closer to Impressionism, while others, like Séguin, fully embraced the Symbolist side. Together, they created a tapestry of styles and subjects, all united by a shared love for Brittany’s spiritual essence and visual power.

Themes and Techniques that Defined the Movement

The Brittany School’s subject matter was steeped in the daily life, legends, and religious customs of the Breton people. Artists often depicted women in traditional black dresses and lace coifs, attending mass or walking solemnly through the countryside. These images captured not only a specific people but also a vanishing world—one untouched by the machinery and moral confusion of the cities. The movement’s interest in these spiritual and rural scenes offered an implicit critique of France’s increasing secularization and industrialization.

Techniques used by Brittany School artists diverged from the brushy realism of their Impressionist peers. They favored Cloisonnism, a method where forms are outlined in dark lines, much like stained glass or cloisonné enamel. This technique, championed by Bernard and Gauguin, emphasized simplicity and flatness over depth and volume. It allowed artists to infuse their works with symbolic meaning and emotional force, rather than just visual accuracy.

Another hallmark of the Brittany School was the use of Synthetism, which synthesized the artist’s feelings, the subject’s form, and the viewer’s emotional response. Colors were bold and often unnatural, chosen not to imitate life but to express deeper truths. The use of non-traditional perspectives, flattened planes, and rhythmical composition created works that felt more like visual prayers than depictions of daily life. The goal was to suggest, not to describe.

These techniques and themes laid the groundwork for later movements like Symbolism, the Nabis, and even early Abstraction. By breaking from naturalistic representation, the Brittany School artists gave themselves freedom to express inner realities. They turned away from fleeting impressions and toward eternal truths, using color and form as tools of revelation rather than replication. Their work was not just about what the eye could see—it was about what the soul could sense.

The Legacy of the Brittany School in Modern Art

The Brittany School’s impact on modern art is difficult to overstate. While it never established itself as a formal institution, its influence rippled outward into major 20th-century movements. The group’s rejection of realism and embrace of symbolism laid the groundwork for modernism’s boldest innovations. Artists like Kandinsky, Matisse, and even Picasso followed trails first blazed in Brittany’s stone villages and shadowy woods.

The Nabis, a group that included Paul Sérusier, Pierre Bonnard, and Maurice Denis, drew direct inspiration from Gauguin’s teachings in Pont-Aven. Formed in the early 1890s, the Nabis emphasized art as a spiritual, decorative, and emotional endeavor. Sérusier’s The Talisman, painted in Pont-Aven in 1888, became a sacred relic for the group. They continued the Brittany School’s dream of blending abstract form with spiritual depth.

In many ways, the Brittany School served as a bridge between Impressionism and the more abstract, expressive styles of the early 20th century. Its artists were among the first to break away from strict representation and embrace intuition and emotion. Their symbolic use of color and form directly influenced Symbolist painters and prefigured the developments of Fauvism and Expressionism. What began in a sleepy Breton village echoed through the studios of Paris and beyond.

Even today, the influence of the Brittany School can be seen in how artists approach the relationship between place, culture, and spirituality. Their belief that art could express deeper truths than mere surface appearances remains a powerful idea. The legacy of the Brittany School is not just a collection of paintings—it is a vision of art as a spiritual act, rooted in tradition but ever-reaching forward.

Visiting Brittany Today: Traces of the School Still Remain

For those looking to walk in the footsteps of the Brittany School, Pont-Aven remains a living museum of artistic memory. The Musée de Pont-Aven, opened in 1985 and fully renovated in 2016, features permanent and rotating exhibitions showcasing works by Gauguin, Bernard, and their contemporaries. Visitors can explore galleries filled with vibrant canvases that once shocked the Paris salons but now stand as pillars of modern art. The museum also offers insight into the village’s artistic and cultural evolution.

Just a short walk from the museum stands Pension Gloanec, the legendary inn where artists gathered to eat, talk, and trade their work. Though it now houses a crêperie and bookstore, the building retains its original charm, with several rooms dedicated to the memory of its former guests. Outside, commemorative plaques tell the story of the Brittany School in both French and English. These locations offer a tangible link to the creative energy that once animated the village.

The natural landscape, too, remains largely unchanged. Coastal paths wind through woods and cliffs, providing the same inspiration that once struck Maufra or Moret. Local churches and chapels, often featured in the paintings, still hold Masses and candlelit processions. Many tourists remark on the sense of timelessness that seems to hang in the air—a sense that this place is somehow still connected to the sacred.

In recent years, Brittany has embraced its role in art history by supporting modern artist residencies, festivals, and workshops. Galleries continue to showcase local talent alongside historical works. The region has managed to preserve its spiritual and visual beauty while welcoming new generations of creatives. To visit Brittany today is to touch a world where the sacred and the artistic remain intertwined.

Key Takeaways

- The Brittany School was an informal art movement rooted in rural Brittany, France, in the late 19th century.

- Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard pioneered new techniques like Synthetism and Cloisonnism in Pont-Aven.

- The group emphasized spirituality, symbolism, and emotional depth over realistic representation.

- Key themes included peasant life, religious tradition, and mystical landscapes.

- The movement’s influence stretched into Symbolism, the Nabis, and early modern art.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Was the Brittany School a formal institution or academy?

No, it was an informal movement of like-minded artists who worked in Brittany during the late 19th century. - Why did artists go to Brittany in the first place?

They sought refuge from industrial cities, drawn by Brittany’s natural beauty and devout rural culture. - What artistic techniques defined the Brittany School?

Cloisonnism and Synthetism—bold outlines, flat color, and symbolic content—were major stylistic traits. - Who were some key members besides Gauguin?

Émile Bernard, Charles Laval, Paul Sérusier, Armand Séguin, and Maxime Maufra were all important contributors. - Can you still see the Brittany School’s legacy today?

Yes, Pont-Aven houses museums, historical sites, and continues to inspire artists worldwide.