Rising above the rooftops of a medieval Spanish city like a spine of stone vertebrae, the Aqueduct of Segovia is among the most iconic monuments of Roman engineering. Stretching over 800 meters through the heart of Segovia and towering nearly 29 meters at its highest point, this awe-inspiring structure has stood for nearly 2,000 years, carrying water and bearing witness to the rise and fall of empires.

Built during the height of the Roman Empire, likely under the reign of Emperor Domitian (81–96 AD) or possibly Trajan (98–117 AD), the aqueduct was designed to transport water from a mountain spring to the bustling urban center of Roman Segovia—then known as Segovia Augusta. It is constructed from unmortared granite blocks, relying on precision-cut stone and gravity alone, a testament to the ingenuity and mathematical skill of Roman architects and engineers.

Unlike many Roman ruins that lie in fragments or have been heavily reconstructed, the Aqueduct of Segovia remains remarkably intact. It was used to carry water until the 20th century, and its continued survival is due in part to the care of local residents and centuries of adaptive reuse. Today, it is not only a national symbol of Spain’s Roman past but also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for its historical and architectural significance.

It’s rare that ancient utility becomes modern icon—but that’s what has happened here. The Aqueduct of Segovia is a bridge between centuries, a functioning machine turned monument, and a masterclass in classical engineering that continues to educate and inspire.

Roman Aqueducts: Function, Form, and Innovation

To understand the Aqueduct of Segovia, it’s essential to grasp the broader context of Roman aqueduct design. These were not merely channels of water—they were symbols of civilization. Rome built aqueducts wherever it settled, linking engineering, hygiene, urban planning, and imperial prestige into a single architectural form.

Aqueducts were built to bring fresh water from distant springs or rivers to cities, baths, fountains, latrines, and even private homes. The Romans perfected the art of water conveyance using gravity-fed systems, calculating the slope of the land with remarkable precision. Most of an aqueduct’s route was underground, but in places where the terrain dropped, monumental arcades were built to maintain the necessary incline.

The key components of a typical Roman aqueduct included:

- Captatio: The water source, often a mountain spring or river

- Specus: The covered channel, usually made of stone, concrete, or brick

- Distribution tank (castellum aquae): A basin where water was collected and regulated

- Bridges and arcades: Used to span valleys and maintain a steady slope

- Maintenance shafts and vents: Installed at intervals for repairs and cleaning

Roman aqueducts were marvels of function-driven architecture. They combined hydraulics, materials science, surveying, and long-distance coordination—often over rough terrain and hostile environments. Many were built with concrete and waterproof cement, but in the case of Segovia, the engineers relied solely on granite and dry masonry.

At its peak, Rome itself had 11 major aqueducts, and Roman colonies across the empire followed suit. From Pont du Gard in France to Valens Aqueduct in Constantinople, these structures conveyed the image of Rome as a bringer of order, health, and technological mastery.

Construction of the Segovia Aqueduct: Precision Without Mortar

The Segovia aqueduct likely began construction in the late 1st century AD, based on stylistic and archaeological analysis. It is generally attributed to either Domitian or Trajan, both of whom initiated large-scale infrastructure projects in Spain and across the western provinces.

The water source lies in the Fuente Fría spring, located in the Guadarrama Mountains, about 17 kilometers (10.5 miles) from the city of Segovia. The aqueduct carried water from this spring through underground channels, open-air trenches, and stone conduits, eventually reaching the city’s distribution tank, where water was routed to various destinations.

What sets the Segovia aqueduct apart is the section that passes through the city—a towering arcade composed of two levels of arches at its highest point. The visible portion contains 167 arches and spans nearly 818 meters, with a maximum height of 28.5 meters (roughly 93 feet) at the Plaza del Azoguejo, where the aqueduct is at its most majestic.

The structure is composed of approximately 20,000 granite blocks, known locally as ashlars, set without mortar. The precision with which these blocks were cut and placed is astonishing. They interlock through friction and balance, held together by gravity and weight alone. The aqueduct’s stability is enhanced by:

- Vaulted arches, which distribute weight efficiently

- Tapered pillars, thicker at the base and narrower at the top

- Keystones, placed at the apex of each arch to maintain compression

Despite centuries of earthquakes, floods, and human activity, the aqueduct has remained structurally sound. This durability has made it a textbook example of Roman dry masonry engineering and a subject of study for architects and historians alike.

Materials and Engineering Techniques

The Segovia aqueduct is a monument to the power of local materials used with global expertise. The stone used is a coarse gray granite, quarried from nearby hills, ensuring that it matched the regional aesthetic while minimizing transportation costs. Granite is extremely hard and durable—an ideal material for load-bearing stone architecture.

Because no mortar was used in the construction, the strength of the structure comes entirely from:

- Weight and gravity: The mass of each block presses downward to hold the structure in place.

- Keystone mechanics: Each arch uses a central wedge-shaped stone to distribute lateral forces.

- Frictional resistance: Precisely cut surfaces and tight joints reduce the chance of slippage.

- Vertical tapering: The columns narrow as they rise, reducing load and increasing visual lightness.

One of the most advanced features is the subtle curvature of the arcade, which is not perfectly straight but slightly adjusted to match the terrain. Roman engineers used plumb lines, leveling tools, and sighting rods to maintain the correct gradient throughout the aqueduct’s entire 17-kilometer length.

Water entered the system at a slight incline—less than 1% grade—ensuring continuous flow without turbulence. The channel was lined with lead, tile, or stone to prevent leakage, and settling tanks were used to filter out sand and sediment along the way.

Although much of this system is now underground or lost to time, segments of the original specus (water channel) remain visible near the upper part of the city, including remnants of the decanter tanks and ceramic piping. These hidden elements complete the picture of a structure that was as sophisticated beneath the ground as it is above it.

The Urban Integration: How the Aqueduct Defines Segovia

One of the most remarkable features of the Aqueduct of Segovia is how it interacts with the urban fabric of the city. Far from being isolated or tucked away like many Roman ruins, the aqueduct runs directly through the heart of Segovia, dominating its central square and connecting various neighborhoods across centuries of city planning.

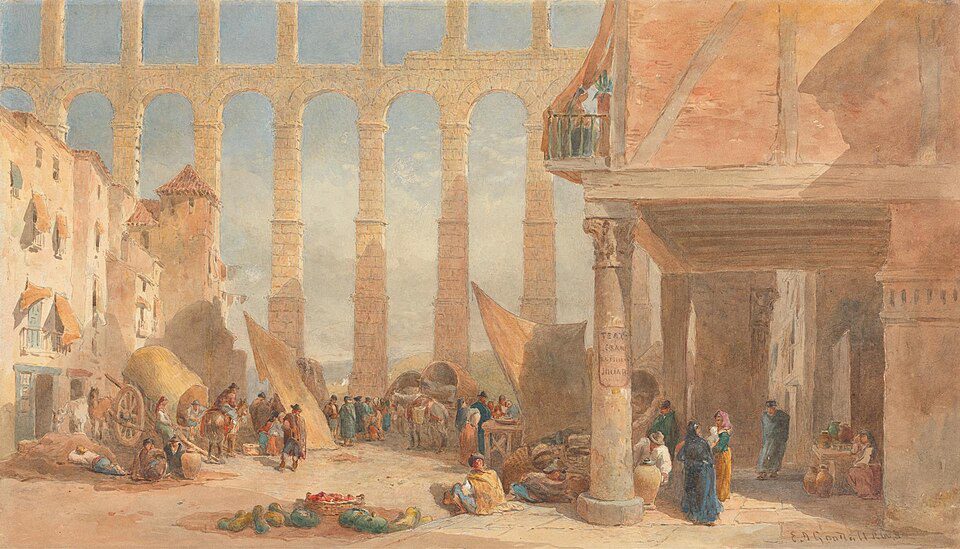

The most famous section—spanning the Plaza del Azoguejo—serves as both a visual focal point and a functional bridge between the lower commercial quarter and the upper medieval core, where the cathedral and Alcázar stand. For centuries, this plaza was the site of markets, festivals, and public gatherings, all conducted under the shadow of Roman arches.

The aqueduct’s integration into the city wasn’t accidental—it reflects a Roman approach to infrastructure as civic theater. Aqueducts were intentionally visible and monumental where they entered cities, signifying not just technological prowess but the benevolence of Roman rule. They delivered more than water—they delivered the empire.

In the medieval and early modern periods, Segovia’s residents continued to live with the aqueduct not as a ruin, but as a living part of daily life. Houses were built alongside its pillars, and small staircases were added to reach the upper city. Local legends and folklore grew around it, giving it mythical as well as practical value.

During the Spanish Renaissance, the aqueduct inspired local architects, who mimicked its arches in cloisters, doorways, and arcaded plazas. It helped set the rhythm and style for Segovia’s architectural identity. Even in modern times, urban planners have preserved sightlines to the aqueduct and integrated pedestrian routes beneath it, maintaining its centrality to city life.

Few monuments—Roman or otherwise—are so deeply woven into the daily life, layout, and symbolism of a city. In Segovia, the aqueduct is not just a remnant of the past. It’s a civic backbone, a visual anchor, and an enduring source of local pride.

Religious and Cultural Symbolism Over Time

While the Aqueduct of Segovia began as a purely utilitarian structure, its meaning evolved over the centuries. As the Roman Empire faded and Christianity spread, the aqueduct took on new symbolic roles—becoming, in effect, a bridge not only for water, but for ideas and identities.

In the Middle Ages, the aqueduct came to be seen as a marvel not of pagan Rome, but of divine will. Folk tales emerged claiming the structure was built overnight by the devil himself, contracted by a young girl tired of carrying water from the mountains. In the end, the girl crosses herself at dawn, and the devil is one stone short of completing his work. A bronze plaque still marks this story at the base of one pillar, showing how religious storytelling reinterpreted Roman achievement.

In Christian iconography, arches were seen as symbols of divine protection and sacred passage. As the aqueduct remained standing while other Roman ruins fell, it came to represent divine favor or saintly intervention. During the Counter-Reformation, Spain’s renewed interest in national Catholic identity embraced the aqueduct as a local miracle.

By the 19th century, with the rise of Romanticism and nationalism, the aqueduct became a symbol of Spanish heritage. Artists and poets portrayed it as a remnant of lost grandeur. Painters like David Roberts and Joaquín Sorolla depicted it in golden light, while scholars began systematic studies of its engineering.

In the modern era, the aqueduct continues to serve as a cultural emblem. It appears on local flags, seals, tourism brochures, and even Euro coinage. Schoolchildren study its design as part of Spanish history. Local festivals, such as Fiesta de San Frutos, include parades and ceremonies near the aqueduct, reinforcing its role as a living symbol.

What began as an aqueduct is now a sacred artifact, a national monument, and a bridge across time—linking Roman order, Christian faith, Spanish resilience, and modern identity.

Preservation, Restoration, and World Heritage Status

Preserving an open-air Roman monument in a living city for nearly two millennia is no small task. The Aqueduct of Segovia has undergone numerous repairs, restorations, and adaptations, each reflecting the priorities and techniques of its time.

The first major documented restoration took place in the 15th century, under Queen Isabella I of Castile, who recognized the aqueduct’s importance and ordered damaged sections rebuilt. Later repairs occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries, often using limestone infill and small amounts of mortar where precision cuts were no longer feasible.

By the 20th century, increased urban traffic and pollution began to erode the stone. Vibrations from cars and buses passing beneath the arches caused microfractures, and modern air pollutants began blackening the granite. In response, a major preservation effort was launched in the 1970s, supported by Spain’s Ministry of Culture and heritage foundations.

Key preservation efforts have included:

- Stone cleaning and desalinization to remove harmful mineral deposits

- Replacement of eroded keystones with matching local granite

- Restriction of vehicular traffic near the main arcade

- Installation of climate and vibration sensors to monitor structural stress

In 1985, the aqueduct was inscribed as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site designation for Segovia, recognizing its outstanding universal value. This designation has helped ensure international support and funding for its preservation.

Today, ongoing maintenance is coordinated by both local and national bodies. Conservation teams use non-invasive technology, such as laser scanning and photogrammetry, to map shifts in the stone and identify vulnerabilities. Yet care is taken to maintain the authenticity of the Roman structure—preserving it not as a frozen artifact, but as a working part of the city’s historical identity.

The Aqueduct Today: Civic Pride and Global Recognition

In the 21st century, the Aqueduct of Segovia is no longer a conduit for water—but it remains a conduit for culture, identity, and national pride. It draws over a million visitors annually, standing as the centerpiece of Segovia’s historic center, and it continues to define the city skyline, its arches framing the landscape like a colonnaded crown.

More than just a tourist attraction, the aqueduct plays an active role in Segovia’s civic life. Festivals, public concerts, parades, and national celebrations often take place beneath its arches, especially in the Plaza del Azoguejo. At night, a subtle lighting system highlights the structure, emphasizing its grace without undermining its gravity.

Local initiatives, often led by schools, museums, and cultural foundations, aim to teach younger generations about the aqueduct’s legacy. Guided walking tours, virtual reality reconstructions, and educational installations now help visitors understand not only the aqueduct’s history but the values it represents—precision, endurance, and civic unity.

In the international arena, the aqueduct is regarded as one of the finest surviving examples of Roman engineering. It is often studied alongside:

- Pont du Gard in France

- Aqua Claudia in Rome

- Valens Aqueduct in Istanbul

However, what sets the Segovia aqueduct apart is its urban integration and structural preservation. While others may be more massive or ornate, few match the degree to which Segovia’s aqueduct remains embedded in daily life, still in its original location, largely untouched by modern reconstruction.

As Spain continues to develop its national heritage programs, the aqueduct remains a flagship site—both for its Roman legacy and for the Spanish stewardship that has preserved it. It is a success story in historic preservation and a model of how ancient infrastructure can become timeless architecture.

Key Takeaways

- The Aqueduct of Segovia was built in the late 1st century AD under the Roman Empire to supply water to the city.

- Made of 20,000 unmortared granite blocks, it is an engineering marvel relying solely on gravity, friction, and geometry.

- It stretches over 800 meters with 167 arches, reaching nearly 29 meters high at its tallest point.

- The structure has survived wars, weather, and centuries of urban development, becoming a symbol of civic and national identity.

- Today, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the best-preserved Roman aqueducts in the world.

FAQs

- How old is the Aqueduct of Segovia?

It was likely built in the late 1st century AD, making it nearly 2,000 years old. - Is the aqueduct still used to carry water?

No—it ceased functioning as a water conduit in the early 20th century but remains fully intact. - How was the aqueduct built without mortar?

The Romans used precision-cut granite blocks, arches, and keystones to hold the structure together by compression. - Can you walk on top of the aqueduct?

No—access is restricted to preserve the structure, but you can walk beside and beneath it. - Why is it famous?

It’s one of the best-preserved Roman aqueducts and a stunning example of ancient engineering still integrated into a living city.