For centuries, artists have turned their gaze to the operating table, capturing scenes of surgery that range from deeply symbolic to disturbingly realistic. These works reveal a time when surgery was not only a physical ordeal but also a public spectacle — often messy, risky, and unfiltered. Before sterile gloves and painkillers, surgeries were grueling events performed in front of curious crowds or inside cold anatomical theaters. In these raw moments, artists found something both horrifying and fascinating to record.

Art’s documentation of surgery reflects more than just a fascination with gore; it also traces mankind’s changing understanding of the human body. From spiritual interpretations in the Middle Ages to the scientific precision of the Renaissance, depictions of surgery reveal shifts in philosophy, medicine, and art itself. These works of surgical art are not just illustrations — they are cultural artifacts that show how we viewed pain, healing, and the boundaries of life. They’re as much about humanity as they are about anatomy.

Why Artists Were Drawn to Surgery

Surgery gave artists a reason to explore the depths of human anatomy while touching on universal themes like suffering and mortality. In an age before photography, painting and drawing were the only ways to visualize the inside of the human body. This overlap between medicine and art created some of the earliest examples of anatomical realism. As artists began to attend dissections and surgical demonstrations, their work took on new levels of detail and emotional depth.

During the early scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, curiosity about the human form flourished. Artists were often employed by physicians or scientists to illustrate medical texts, turning messy procedures into carefully staged, sometimes elegant, compositions. In these images, death was not sanitized — it was studied. Artists captured both the grim work of cutting into flesh and the sense of awe that came with unlocking the body’s inner secrets.

Cutting Edge in the Middle Ages – Surgery Before Sterility

In the medieval period, surgery was closer to carpentry than science. It was often performed by barber-surgeons who lacked formal medical training and relied on crude tools such as saws, forceps, and knives. There was no concept of germs or sanitation, and anesthesia as we know it did not exist. Bleeding, infection, and death were common outcomes, and this grim reality made its way into the art of the time — albeit with heavy religious overtones.

Instead of realistic depictions of operations, medieval surgical art leaned on allegory and saintly intercession. Surgeries were often shown as miraculous events, performed by holy figures rather than mortal physicians. These scenes blurred the line between medicine and miracle, reinforcing the idea that healing was ultimately a divine act. Art from this period reveals more about religious belief than medical practice — though some techniques, like bloodletting, were illustrated with eerie clarity.

Saintly Surgeons and Surgical Miracles

Saints Cosmas and Damian, early Christian martyrs, were frequently portrayed performing miraculous surgeries in medieval artwork. In one well-known 15th-century painting, The Miracle of the Black Leg (c. 1494), the twin saints are shown transplanting the leg of a deceased Ethiopian man onto a white European patient — a feat meant to symbolize divine power rather than medical possibility. This painting is attributed to an anonymous artist working in the Spanish-Flemish style and reflects the era’s understanding of surgery as spiritually charged.

These saints were often venerated as protectors of surgeons and apothecaries. Their images appeared in churches, manuscripts, and altarpieces, especially across Southern Europe. Though their medical miracles were fictional, they became symbols of hope in an age when most surgeries were fatal. In these portrayals, the body is passive, often unconscious or even dead — reinforcing that only through divine intervention could such procedures succeed.

The Renaissance: Blood, Brilliance, and Anatomy

The Renaissance marked a turning point in the depiction of surgery in art, as science and realism replaced medieval mysticism. This was an era of intellectual rebirth, and artists became deeply involved in the study of the human body. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) famously dissected dozens of cadavers in Milan and Florence between 1487 and 1513. His anatomical drawings, though not intended for publication, remain some of the most accurate visual records of human anatomy ever produced.

This period also saw the publication of groundbreaking anatomical texts that blended medical knowledge with artistic excellence. The most famous of these is De humani corporis fabrica (1543), written by Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564). Vesalius corrected centuries of errors in Galenic anatomy and emphasized the importance of direct observation and dissection. His work not only transformed medical education but also influenced generations of artists and scientists.

Andreas Vesalius and the Birth of Anatomical Art

Vesalius was just 29 years old when he published Fabrica in Basel in 1543. The illustrations, likely created by Jan Stephan van Calcar (c. 1499–c. 1546), a student of Titian, brought a level of artistic refinement to anatomy that was unprecedented. The book featured detailed woodcut images of dissected bodies posed as if in classical sculptures, set against dramatic landscapes. The pairing of graphic realism with aesthetic sensitivity gave anatomical art a new cultural legitimacy.

These images weren’t merely decorative — they were tools for learning. Vesalius used them to argue that anatomy should be based on actual dissection, not ancient texts. His influence was immediate and lasting; medical schools across Europe adopted his approach. Artists, too, took note — anatomical accuracy became essential to painting the human figure. Through Vesalius, surgery became both a science and an art.

Operating in Public – Theater, Spectacle, and Surgeons

By the 17th century, the practice of surgery had moved into public view — literally. Anatomical theaters, such as those in Padua (built 1594) and Leiden (1597), were designed like miniature coliseums where the public and students could watch dissections and surgical procedures. These spaces transformed surgery into performance, where the skill of the surgeon and the reactions of the crowd were part of the experience. Art from this period reflects the tension and theatricality of these live demonstrations.

While dissection was often educational, surgery remained brutal. Patients were typically conscious, restrained, and in agony. Artists of the time captured this intensity, showing operating tables surrounded by students, candles, and ominous tools. The realism of these scenes began to increase, especially as interest in empiricism and observation grew. The human body, once veiled in taboo, was now fully exposed — sometimes literally flayed open on canvas.

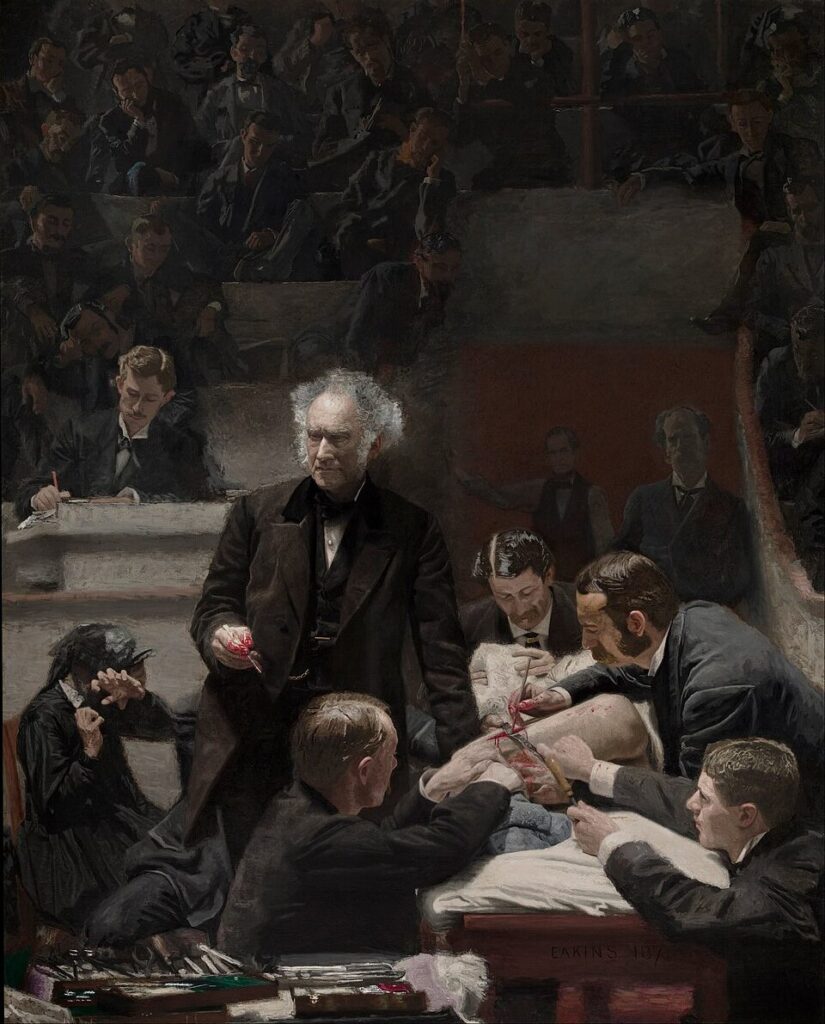

Thomas Eakins’ “The Gross Clinic” – Realism Meets Revulsion

One of the most visceral paintings of surgical realism came much later, in 1875, with Thomas Eakins’ The Gross Clinic. Eakins (1844–1916), an American realist painter and anatomy instructor, depicted Dr. Samuel D. Gross performing a surgery at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. The painting shows Dr. Gross holding a blood-soaked scalpel while calmly lecturing to a group of students. Meanwhile, the patient — partially cut open — lies beneath a curtain of shadow and surgical focus.

The painting was initially rejected by the art establishment for being too graphic, but it later gained recognition as a masterpiece of American realism. Eakins’ unflinching depiction of modern surgery reflected not only medical progress but also the endurance of human suffering. His background in anatomical study gave the piece authenticity, while his artistic skill made it compelling. Today, The Gross Clinic is considered one of the most important works in American art history.

Gruesome Yet Grand – The Golden Age of Medical Painting

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, surgery began to appear in art as a subject of progress rather than horror. Scientific developments, such as antisepsis and anesthesia, started to shift public perception. Paintings of surgeries were now used to celebrate the achievements of medical professionals and the institutions that trained them. These works emphasized the heroism and skill of the surgeon, often downplaying the pain involved.

Portraits of famous doctors became popular, as did large-scale historical paintings of landmark operations. These images were often commissioned by medical societies or hospitals to commemorate advances in technique. Yet even in these polished representations, the emotional gravity of surgery remained visible. Artists sought to balance the scientific dignity of the event with the human vulnerability of the patient.

The Agony in Detail – Charles Bell’s Surgical Sketches

Sir Charles Bell (1774–1842), a Scottish surgeon and artist, brought a different sensibility to the depiction of surgery. Rather than grand oil paintings, Bell produced raw, expressive sketches that showed patients mid-procedure or in moments of intense pain. His works, such as those in Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery (1821), were both instructional and deeply emotional. They revealed the brutal physical toll of surgery in a way few artists dared.

Bell was trained in both medicine and fine art, having studied at the Royal Academy in London. His surgical illustrations focused on the face and nervous system, with a particular interest in facial expressions of suffering. These images served as medical documentation but also stood as artistic studies of human endurance. His blend of accuracy and empathy influenced both surgeons and artists alike.

Morbid Fascination – Surgery in 20th Century and Surreal Art

By the 20th century, the depiction of surgery in art had taken a psychological turn. Rather than illustrating medical procedures for educational purposes, artists began to use surgical imagery to explore trauma, identity, and alienation. The horrors of two World Wars and rapid technological change led many to see the body as fragmented and vulnerable. Surgery became a metaphor for mental and societal breakdown.

Artists no longer confined themselves to accurate anatomical renderings. Instead, they presented distorted, surreal, or symbolic visions of the body under the knife. Blood, stitches, scars, and surgical instruments appeared not as tools of healing but as emblems of existential dread. These works often blurred the lines between surgery, violence, and self-transformation — reflecting a world increasingly shaped by industrial medicine.

Frida Kahlo’s Surgical Self-Portraits

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954), the iconic Mexican painter, created some of the most personal and haunting depictions of surgery in modern art. After a near-fatal bus accident in 1925, she endured over 30 operations throughout her life. Her paintings often reflect the trauma of these procedures, turning her own body into a recurring subject. In The Broken Column (1944), she shows herself naked, her torso split open and held together by nails and metal corsets.

Kahlo used surgical imagery not just to document her pain but to make statements about gender, resilience, and personal suffering. Her works merge the medical and the mythic, transforming surgical scars into symbols of strength. Unlike the clinical precision of Renaissance drawings, Kahlo’s art is emotional, intimate, and symbolic. She reclaimed the surgical gaze, making herself both subject and storyteller.

Surgical Art Today – Between Medicine and Morbidity

Contemporary art continues to engage with surgery, though often in conceptual or critical ways. Advances in medical imaging, robotic surgery, and biotechnology have created new opportunities for visual exploration. Today’s artists might use video, digital simulations, or installations to comment on the surgical experience. Some works critique the commercialization of healthcare or explore ethical dilemmas in medical practice.

Others return to hyperrealism, capturing procedures with forensic detail. These artworks may serve as educational tools or as expressions of reverence for the complexity of the human body. The boundary between medical illustration and fine art is increasingly blurred. While the operating room has become more sterile, the emotions surrounding surgery remain raw.

Modern Medical Illustrators – Art in the Service of Science

One of the most influential medical artists of the 20th century was Frank H. Netter (1906–1991), a physician who created over 4,000 medical illustrations. His work is still used in textbooks and classrooms around the world. Unlike emotionally driven art, Netter’s illustrations were designed to educate — showing surgical steps, anatomical structures, and clinical procedures with clarity. Yet his skill as a draftsman gave these images a subtle beauty.

Today, medical illustration is a thriving field that combines science and aesthetics. Illustrators undergo formal training, often with backgrounds in both biology and art. Their work aids in everything from surgical planning to patient education. In a way, they carry forward the tradition started by Vesalius — turning the complexities of the human body into visual knowledge.

Key Takeaways

- Medieval surgical art often reflected religious themes rather than medical reality.

- The Renaissance brought anatomical accuracy and scientific curiosity to surgical depictions.

- Public dissections and surgical theaters were common subjects for 17th–19th century artists.

- Modern artists like Frida Kahlo used surgical imagery to explore personal and political themes.

- Contemporary medical illustration continues to blend scientific precision with artistic skill.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was the first artist to study human anatomy through dissection?

Leonardo da Vinci was among the earliest artists to study cadavers for accurate anatomical drawings. - What is the significance of Andreas Vesalius’s Fabrica?

It revolutionized anatomical science by combining detailed dissection with elegant artistic illustration. - Why did surgery become a public spectacle in the 1600s?

Educational dissections and public operations were used to teach students and entertain the public. - How did Frida Kahlo incorporate surgery into her art?

She used her surgical scars and experiences as symbols of pain, strength, and identity. - Are medical illustrations considered art today?

Yes, especially when created with high skill and used to communicate complex medical ideas.