When it comes to historical villains, few have sparked as much fear and fascination as the Thuggee cult. This underground society of criminals, whose name gave rise to the word “thug,” is often remembered for its brutal rituals and a reign of terror that lasted for centuries. But what’s even more chilling is how the portrayal of the Thuggee in art and media has amplified their sinister reputation. In this article, we’ll dive deep into the history of the Thuggee, the art they inspired, and the eerie ways their legacy has survived through film, literature, and even pop culture.

Origins of the Thuggee: The Brotherhood of Death

The Thuggee cult emerged in India, likely as early as the 13th century. However, they didn’t gain widespread infamy until the 18th and 19th centuries, when British colonial forces uncovered their secret network. The Thuggee were a group of criminals who worshipped the Hindu goddess Kali, known for her association with death and destruction. According to their beliefs, they were enacting Kali’s will by murdering innocent travelers, often in the most deceptive and cold-blooded ways.

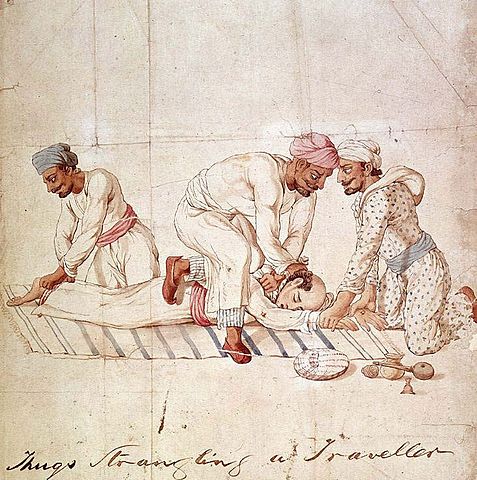

The cult operated by befriending unsuspecting travelers on the road. They gained the trust of their victims before attacking. The signature method of killing was strangulation with a cloth, usually a ceremonial sash called a rumal. This kept the murders quiet and clean—just as Kali allegedly desired.

Historian Mike Dash, in his detailed book Thug: The True Story of India’s Murderous Cult, explained that the Thuggee believed they were chosen by Kali to maintain the balance between life and death. “Each death was seen as an offering to the goddess, a way to keep her satisfied and, in turn, protect the world from her wrath,” Dash wrote. It’s a grim and fascinating paradox—murdering to preserve cosmic order.

Thuggee’s Role in British Colonialism

British colonizers in India saw the Thuggee as a direct threat, both to public safety and to their control over the Indian population. As the cult’s influence spread, the British initiated a campaign to root out its members. By the early 19th century, British officials launched the so-called “Thuggee and Dacoity Department,” a specialized force tasked with eradicating this menace.

The capture and execution of many Thuggee leaders gave rise to countless reports and sensationalized tales of their activities. These stories spread rapidly through the British press and soon infiltrated Western art and literature. The idea of a secret cult that ritualistically killed its victims for religious purposes ignited both fascination and horror in Europe.

In 1839, Sir William Henry Sleeman, a British officer stationed in India, published accounts of the Thuggee in his book Ramaseeana, or a Vocabulary of the Peculiar Language Used by the Thugs. Sleeman’s work wasn’t just an academic study—it was full of graphic descriptions of the Thuggee’s alleged activities, which played directly into the Victorian appetite for tales of the exotic and macabre. His work would become a key influence on the portrayal of the Thuggee in art and fiction.

Thuggee in Literature: From Sensationalism to Symbolism

The cult’s blood-chilling rituals didn’t stay confined to historical accounts for long. Literature, particularly in Victorian England, latched onto the Thuggee as a symbol of barbarism and the “exotic” dangers of the East. Writers used the cult as an embodiment of both moral decay and the untamed wilds of India.

One of the most famous literary depictions of the Thuggee is found in Confessions of a Thug (1839) by Philip Meadows Taylor. The novel is written as a first-person account of a Thuggee member and offers readers a disturbing view of the cult’s mindset. While fictional, Taylor’s narrative was presented as being based on real events, which only added to its shocking impact.

The character of Ameer Ali, the novel’s protagonist, serves as both a cautionary figure and a tragic anti-hero. He’s depicted as being torn between his allegiance to the cult and his desire to live a more conventional life. The internal conflict in Ali’s character deepens the horror—there’s a human element to his monstrosity, making the Thuggee all the more terrifying. This novel became wildly popular in Victorian England, and its themes influenced other writers and artists who explored India in their works.

Moreover, Taylor’s depiction of the Thuggee inspired a wave of Western fascination with secret cults, leading to the romanticizing of their violence. The Thuggee became a kind of shorthand for a mysterious, dangerous force beyond Western understanding.

Visual Arts: Dark Imagery and Orientalism

Art didn’t escape the allure of the Thuggee cult. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, artists in Europe created paintings, engravings, and illustrations depicting the Thuggee in action—strangling their victims, performing sacrifices, and plotting in the shadows. These pieces often emphasized the exotic and terrifying nature of the cult, feeding into the Orientalist stereotypes that were prevalent at the time.

Orientalism, in simple terms, is the Western depiction of Eastern cultures as mysterious, uncivilized, and inferior. The Thuggee fit neatly into this narrative. Paintings from this era often show the cult members as dark, shadowy figures lurking in the background of lush Indian landscapes, ready to pounce on unsuspecting travelers. The use of rich, deep colors contrasted with violent imagery heightened the sense of danger and intrigue.

One notable example is Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting The Prisoner (1861), which, although not explicitly depicting Thuggee members, embodies the Orientalist fascination with Eastern violence and captivity. The sense of lurking menace in the composition—figures emerging from the shadows—mirrors many Western portrayals of the Thuggee during this period.

Thuggee in Film: Indiana Jones and Beyond

It’s almost impossible to discuss the Thuggee without mentioning Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). The film famously features a group of Thuggee worshippers as the main antagonists, led by the terrifying Mola Ram. Though heavily fictionalized and exaggerated, the film brought the Thuggee cult into modern pop culture, cementing their reputation as one of history’s most sinister groups.

But let’s be honest: Temple of Doom is hardly a documentary. The portrayal of the Thuggee in the film is riddled with inaccuracies and sensationalized to fit the adventure genre. Mola Ram’s heart-ripping rituals, for instance, have no historical basis in the Thuggee cult’s practices. However, the film successfully capitalized on the existing Western fascination with the Thuggee, transforming them into cinematic villains of near-mythical proportions.

Despite the inaccuracies, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom played a pivotal role in shaping how modern audiences view the Thuggee. The film’s impact is undeniable, sparking discussions around the cultural representation of historical figures in media. Critics have pointed out that the film perpetuated harmful stereotypes about Eastern cultures, particularly through its portrayal of religious fanaticism and violence.

Nevertheless, Temple of Doom continues to be a reference point whenever the Thuggee cult is mentioned, reinforcing the idea that art and media play a significant role in how we understand history.

The Thuggee in Photography and Modern Media

Interestingly, photography has also played a role in the portrayal of the Thuggee, albeit in a more documentary style. Colonial-era photographs often showed captured or executed Thuggee members, posed by their British captors. These images were distributed widely and served as a grim reminder of British dominance over the “savage” cult.

Even today, the legacy of the Thuggee lives on in various forms of modern media. Television series, graphic novels, and podcasts have all tapped into the allure of this cult. True crime fans, in particular, are drawn to the macabre rituals and secretive nature of the group. The Thuggee’s story has all the elements of a thrilling crime saga: mystery, betrayal, religious zealotry, and a chilling body count.

In a recent episode of the true-crime podcast Casefile, the host delved into the Thuggee’s history, narrating the gruesome details of their crimes with a modern, investigative tone. The podcast even drew parallels between the Thuggee and modern-day serial killers, highlighting the human fascination with ritualistic killing across time and culture.

Artistic License and Historical Reality

While the Thuggee cult’s actions were certainly horrific, it’s crucial to remember that much of what we know about them has been filtered through a colonial lens. The British had every reason to demonize the Thuggee, using them as a justification for expanding their control over India. Many historians now believe that the scale of the Thuggee’s operations was exaggerated, turning them into larger-than-life villains in British accounts.

This brings up an important question: how much of what we know about the Thuggee is true, and how much is artistic embellishment? The line between fact and fiction is blurred when it comes to their portrayal in media. While their crimes were real, the sensationalism around their rituals and motives has been magnified over time.

Artists, filmmakers, and writers have all taken liberties in portraying the Thuggee, often bending historical facts to fit a particular narrative. Whether this is a disservice to history or simply a reflection of human nature’s need for gripping stories is up for debate.

Conclusion: The Lasting Impact of the Thuggee in Art and Media

The Thuggee cult’s sinister rituals have left a lasting mark, not just on history but on art and media as well. Their portrayal has evolved from terrifying historical accounts to symbols of dark mystery and villainy in popular culture. From the pages of Victorian literature to the action-packed scenes of Indiana Jones, the Thuggee continue to fascinate and horrify in equal measure.

But as we consume these depictions, it’s worth remembering that history is often filtered through the lens of those who tell it. The British colonial narrative certainly painted the Thuggee as irredeemable monsters, but the truth may be more complex than that. Regardless, the cult’s influence on art and media remains undeniable—a testament to the enduring power of fear in storytelling.

If nothing else, the Thuggee remind us of the strange appeal of the macabre. As long as people seek thrills and mysteries, the Thuggee cult will continue to live on in our collective imagination, their shadowy figures always lurking just out of sight.

And with that, we close the curtain on one of history’s most chilling tales. Sleep well!