In a world where distractions dominate, the ability to focus and notice details is becoming increasingly rare. Observation isn’t just about looking—it’s about truly seeing, analyzing, and understanding what lies before you. Developing this skill can improve nearly every area of life, from making sound decisions to noticing when something is out of place. Art offers a concrete method to cultivate this awareness in a disciplined and productive way.

Visual discernment has always been crucial in professions demanding high precision. Consider how a surgeon must recognize subtle differences in tissue, or how a detective picks up on minute clues at a crime scene. These are not just intuitive gifts; they can be trained. Artists, who routinely analyze color, form, and space, demonstrate the power of this kind of vision.

Even in day-to-day settings, better observation makes a difference. From recognizing facial expressions to remembering where you placed your keys, attention to detail improves efficiency and strengthens relationships. The practice of art—drawing, in particular—can help embed this attention into the way you perceive the world.

Art, by its nature, demands a slowing down. In contrast to the rushed scanning we do on phones or in fast-paced jobs, making or viewing art insists on patience. This process naturally nurtures mindfulness and heightens one’s ability to detect nuance—qualities sorely needed in today’s society.

The Lost Art of Paying Attention

Modern culture promotes fast consumption of media and rapid scrolling, eroding our capacity for deep attention. In earlier centuries, attention was not optional—it was essential. Farmers noticed the color of the sky for weather, and hunters read tracks with trained eyes. Likewise, artists throughout history trained themselves to see what others missed, finding patterns and truths in even the smallest gestures.

By reintroducing these principles through art, we can reclaim an old form of attentiveness. Practicing art returns the individual to a state of focused presence, an antidote to the fragmented mindset pushed by modern technology. The decline of cursive handwriting and art classes in schools has only accelerated the loss of visual intelligence.

Before photography, drawing was the only way to record visual information. This required careful observation and skill. Learning to draw, even today, forces the mind to reconstruct that old-fashioned attention to detail.

People who consistently observe well tend to become better problem solvers. They are harder to deceive, quicker to notice inconsistency, and more equipped to respond with accuracy—attributes that should be cultivated and passed down, not lost.

The Practical Benefits of Seeing Clearly

Strong observation improves performance in fields as diverse as mechanical repair, education, and aviation. Pilots, for example, are trained to notice subtle changes in instrument readings or weather patterns. Artists, similarly, develop the discipline to notice subtle tonal shifts and form distortions—skills which can translate into real-world vigilance.

Children who develop visual observation early tend to excel in reading, math, and even music. They learn to differentiate shapes and patterns, creating stronger mental maps. This is why early exposure to drawing and visual games is more than recreational—it’s educational and developmental.

In law enforcement, officers trained in forensic sketching or facial recognition often begin their development with observational drawing. They are better at identifying body language, spotting inconsistencies in stories, and recalling faces. These are not abstract benefits—they’re the direct result of learned focus.

Even in a business environment, better visual comprehension can improve presentations, product design, and spatial planning. It’s not about becoming a professional artist; it’s about cultivating an essential skill that benefits nearly every domain of life.

The Link Between Art and Observational Precision

Art is not about imagination alone. It begins with clear-eyed observation. Artists don’t invent the world—they interpret it by first studying it. The great works of art in museums across the globe all begin with a meticulous examination of reality, filtered through a trained mind and hand.

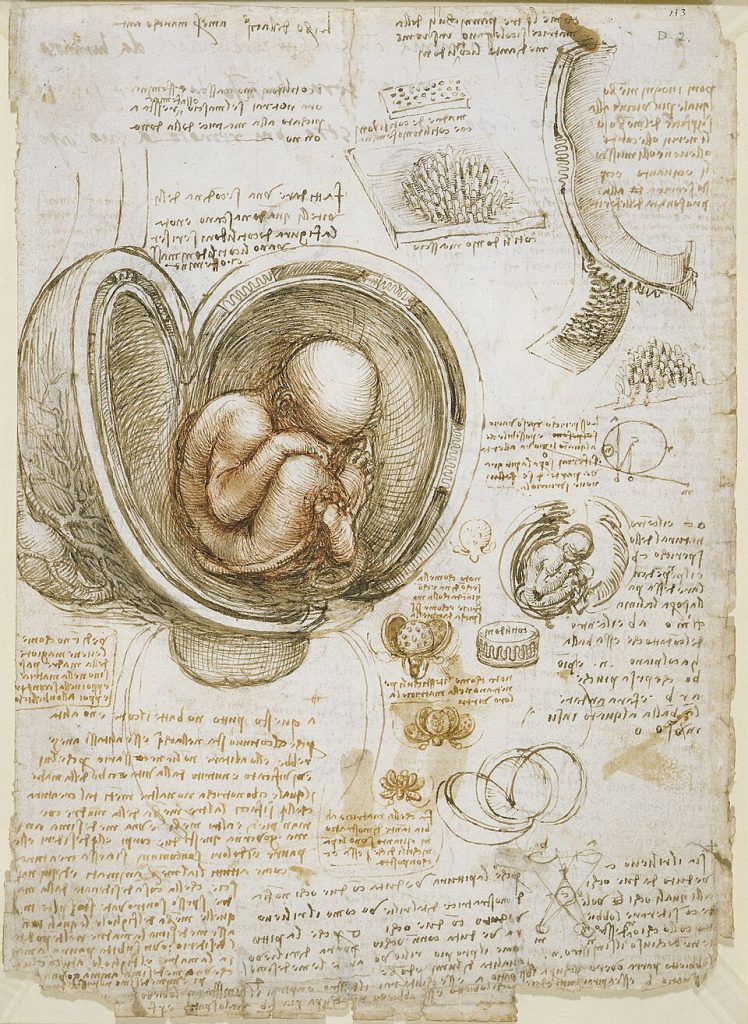

The artist’s skill in capturing reality is not guesswork. It’s the product of hours, weeks, or even years of measured seeing. Michelangelo, for instance, spent long periods observing the human body in anatomical dissections before carving figures like David in 1504. This intense scrutiny gave his work unmatched power and accuracy.

Observation also reveals character. Portraitists from the 16th to the 19th centuries were renowned not only for their technique but for their ability to capture a subject’s inner life. That skill didn’t come from imagination—it came from deep, unblinking observation.

Training the eye doesn’t require talent, but effort. Anyone can improve their powers of perception by learning the artistic principles that refine how we see. Proportion, light, line, and volume are all tools that, when studied, sharpen the mind’s eye.

Seeing Is Not the Same as Looking

There’s a crucial difference between glancing at something and truly seeing it. Most people look at a tree and recognize “tree.” The artist, however, breaks down the branches’ angles, the texture of the bark, and the way the light plays on the leaves. This kind of vision is cultivated.

From as early as the 15th century, European painters like Jan van Eyck created works so detailed that modern viewers are stunned by their realism. This wasn’t photographic mimicry—it was observation raised to the level of visual philosophy. Seeing meant understanding structure, depth, and symbol.

Scientific illustrators in the 18th and 19th centuries also trained themselves to distinguish subtle features of insects, plants, and bones. This work was critical to the development of biology and medicine. Their skills were first rooted in art.

Once you start truly seeing, it’s hard to go back. Your environment comes alive with detail. You begin to notice shadow patterns on buildings, reflections in puddles, and shifts in facial expressions. That’s not magic—it’s the fruit of trained observation.

Training the Eye Like a Craftsman

Much like a carpenter learns to read wood grain, the artist trains the eye to measure angles and proportions accurately. In fact, many trades rely on observational skills: blacksmiths judging the color of metal, tailors noticing fabric tension, or chefs reading the subtle cues of a dish nearing perfection.

Artists use tools like sighting sticks or viewfinders to break down visual information. These tools train the eye to interpret what it sees more precisely, blocking out distractions and focusing attention. The process might seem mechanical, but it strengthens perceptual accuracy over time.

The 19th-century French academic tradition emphasized observation through repetition. Students copied casts, drew from life, and studied under strict guidance. This method, used in ateliers from Paris to Philadelphia, built a strong foundation of disciplined seeing.

Craftsmanship is about patience, humility, and repetition. Artists who learn to see like craftsmen not only produce better work—they develop virtues. And those virtues carry over into daily life, strengthening attention, integrity, and careful thought.

Drawing as a Tool to Strengthen Focus

Drawing is one of the simplest, most powerful exercises for developing attention. It forces the eye and hand to coordinate in real time. There’s no room for distraction when you’re trying to capture the subtle curve of a cheek or the shifting edge of a shadow. This intensity builds cognitive stamina.

Unlike photography, drawing engages the brain’s memory and motor centers simultaneously. You must interpret spatial relationships, judge proportions, and translate that into line and tone. The result is not just better art—it’s a sharper mind.

Scientific studies have shown that people who regularly draw develop better visual memory and concentration. This is because drawing strengthens the prefrontal cortex, which governs focus and planning. In fact, some medical schools have reintroduced drawing into their curriculum to help students see anatomical structures more clearly.

Most importantly, drawing helps individuals slow down. In a fast-paced world, that alone is a transformative skill. Focused observation through drawing creates mental calm, not unlike the effects of prayer or meditative silence.

The Contour Drawing Exercise

Contour drawing is one of the oldest exercises in art education. It requires you to draw the edge of a form slowly and without lifting your pencil. The goal is not a perfect image, but total focus on the form’s outline. This develops hand-eye coordination and acute awareness of shape.

First popularized in American art schools during the mid-20th century, contour drawing forces you to pay attention. Blind contour, in particular—where you don’t look at your paper while drawing—trains you to rely entirely on what you see. Mistakes are not only accepted—they’re embraced as signs of attention.

This method has roots in older academic practices. Charles Bargue’s drawing course from the 1860s emphasized similar techniques in its early plates. Students learned to train their eyes long before adding any stylistic flair.

Spending even ten minutes a day on contour drawing can rewire your brain for better attention. It doesn’t require expensive tools—just a pencil, paper, and focused time.

Value Studies and Light Awareness

Value studies involve rendering an object using a range of lights and darks. This improves one’s sensitivity to subtle shifts in shadow, helping develop a sharper eye for spatial form. Artists use charcoal or pencil to create gradients, analyzing how light wraps around surfaces.

Painters like Caravaggio and Georges de La Tour in the 1600s were masters of light. Their works demonstrate a deep understanding of value—one honed through continual study. Observing their paintings teaches artists how to notice delicate contrasts in everyday objects.

Light observation helps beyond the canvas. It improves night driving, reading facial expressions, and understanding natural lighting in photography. The more you train your eyes to notice contrast, the more details you pick up in the real world.

Students in classical ateliers spend weeks doing value studies before ever using color. This isn’t busywork—it’s a sharpening of perception. Learning to see light and shadow clearly is foundational to both art and life.

- Top 5 Drawing Exercises to Boost Focus

- Blind contour drawing (no peeking!)

- Negative space studies

- Value scale rendering (1 to 10 gradation)

- Timed still life sketches (5-minute sessions)

- Master copy sketching from Bargue plates

Art Appreciation for Mental Discipline

Art appreciation isn’t just a cultural exercise—it’s a mental discipline that cultivates patience, awareness, and discernment. Unlike watching videos or flipping through social media, spending time with a single painting demands sustained attention. This teaches the viewer to slow down, examine details, and reflect deeply. That alone strengthens observation in a way few other activities can.

In galleries and museums, visitors often rush through hundreds of pieces in a short time. But trained viewers, including artists and art historians, will spend twenty minutes or more studying one painting. They notice brushwork, color harmony, lighting, symbolism, and composition. This kind of prolonged engagement exercises the same cognitive muscles required for careful thinking in other fields.

Consider the experience of viewing Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665). At first glance, it seems simple. But with patient looking, the subtle gradations of light, the delicate rendering of the eye, and the enigmatic facial expression all become more profound. This sort of slow looking fosters both intellectual and emotional insight.

Appreciating art in this way isn’t passive entertainment. It’s a form of mental training—like reading Scripture or studying classic literature. It teaches you to pay attention, ask questions, and look beneath the surface. That habit, once formed, carries over into all areas of life.

Learn to Read Visual Cues in Paintings

Every painting is a visual language, and every detail is deliberate. Artists use compositional tools to guide the viewer’s eye across the canvas. Understanding how those tools work sharpens one’s ability to notice visual cues in the world around us.

For example, in historical paintings, a diagonal line often creates a sense of motion or tension. Look at Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Socrates (1787). The use of strong horizontals and verticals organizes the scene, drawing your attention to Socrates’ hand and the expressions of those around him. These choices are not random—they’re visual rhetoric.

Learning to identify focal points, framing, and contrast trains the eye to read visual messages intentionally. This isn’t just helpful in art—it’s beneficial in everyday interpretation of media, advertising, and design. The more you understand visual hierarchy, the less likely you are to be misled by manipulative imagery.

In the same way a skilled reader parses sentences, a trained viewer can “read” a painting line by line, shape by shape. Over time, this teaches discipline, critical thinking, and a deeper sense of visual clarity.

The Old Masters as Visual Teachers

The Old Masters didn’t rely on gimmicks or special effects. Their work was built on observation, discipline, and deep study. Learning to appreciate these artists—Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Raphael—opens a window into both their minds and their visual world.

Rembrandt’s portraits from the 1600s are particularly rich in psychological observation. His self-portraits, painted over decades, reveal an aging face rendered with brutal honesty. In Self-Portrait with Two Circles (c. 1665–1669), every wrinkle, shadow, and reflection is treated with reverence and precision.

These works were not just about beauty—they were about truth. They show us what happens when someone takes the time to truly look. For viewers today, they’re opportunities to train one’s own eye and judgment by learning from visual masters.

Studying the Old Masters reinforces the idea that art is not instant. It’s the product of patience, structure, and vision—qualities that form the backbone of strong observation.

Mastering Observation Through Sketchbooks

A sketchbook is more than a notebook of drawings. It’s a personal laboratory of perception—a place where visual thought is recorded, tested, and refined. For centuries, artists and naturalists alike used sketchbooks not just to capture what they saw, but to train themselves to see better.

Leonardo da Vinci kept extensive sketchbooks throughout his life, beginning in the 1480s. His pages include anatomical studies, engineering diagrams, botanical illustrations, and notes on light and shadow. These books show not only his artistic genius but his relentless curiosity and observational rigor.

Keeping a sketchbook requires you to confront your own visual limits. You may think you’ve seen a building clearly, but once you try to draw it, missing details become obvious. Over time, this self-correction builds both skill and humility.

More than that, sketchbooks build habits. Drawing daily—even for a few minutes—reinforces focus and strengthens the eye. Like a daily walk or prayer routine, it becomes a way of grounding the mind and sharpening attention.

The Habit of Daily Visual Logging

Making sketching a daily practice doesn’t require elaborate materials or complicated subjects. A cup of tea, your hand, a pair of shoes—these all make excellent subjects. What matters is consistency and intention. Daily sketching creates a visual log of your perceptions and progress.

Artists like John Singer Sargent and Winslow Homer frequently used sketchbooks during their travels. Sargent’s fast pen-and-ink studies reveal a constant eye for shape and form, even while moving through unfamiliar places. These pages document not just locations, but moments of deep looking.

For beginners, even ten-minute sketches can have a strong effect. Over time, you’ll start noticing how light falls on everyday objects, how angles shift with perspective, and how details emerge when you slow down. That’s the heart of observation—seeing with clarity.

Logging your visual world helps build awareness. Over time, the habit rewires how you see everything: people, nature, architecture, and more.

How to Use Sketchbooks for Visual Analysis

Sketchbooks aren’t only for drawing. They’re excellent tools for visual analysis—breaking down scenes, noting visual patterns, and asking questions about form and structure. This can include diagramming a composition, listing observed colors, or annotating a shadow’s direction.

Many art schools teach students to notate in their sketchbooks—writing down what they see and how they see it. These notes become as important as the drawings themselves. They teach you to articulate what your eye is doing, turning passive seeing into active thought.

In the 19th century, art critic and educator John Ruskin emphasized sketchbooks as tools of moral and visual clarity. He believed that by drawing something, you honored it and paid it the attention it deserved. His field books, filled with architectural studies and landscapes, remain influential to this day.

By reviewing old sketchbook pages, you can track your own visual development. You begin to see how your sense of proportion, light, and form has improved over time. That reflective process strengthens not just skill, but awareness.

How Classical Training Shapes the Observant Mind

Classical art education focused on structured, repeatable methods of training the eye. Rather than encouraging self-expression first, it demanded accuracy, discipline, and patience. This form of training, dominant in the 17th through 19th centuries, emphasized sight-size drawing, cast studies, and copying master works.

Students in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris or the Royal Academy in London spent years perfecting their ability to see and replicate form. They began with plaster casts of ancient sculptures, progressed to live models, and only later tackled complex compositions. Each step trained them to see relationships, measure proportions, and understand structure.

This system reached its peak in the 19th century with educators like Charles Bargue and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Bargue’s Cours de dessin, published in the 1860s, was a structured program of drawing plates. These plates remain in use today in ateliers across Europe and America for training the eye through repetition.

Rather than being outdated, these classical methods have seen a resurgence. Schools such as the Florence Academy of Art and the Grand Central Atelier in New York now teach traditional techniques. Their students don’t just draw—they learn to see with remarkable clarity and intention.

Bargue Plates and Sight-Size Drawing

The Bargue drawing course begins with precise line drawings of classical sculptures, designed to teach visual measurement. Students are trained to copy the plates exactly, comparing their drawings with the original side-by-side using the sight-size method.

Sight-size involves placing the subject and drawing at the same scale and distance, so errors become immediately visible. This method improves accuracy by training the eye to compare angles, shapes, and values directly. It’s slow work, but immensely powerful for training observation.

Using Bargue plates develops the ability to notice proportion errors that would otherwise go undetected. Students might spend a week on a single drawing—not to impress others, but to train themselves to see more clearly.

Many accomplished artists, including Vincent van Gogh, used the Bargue course in their training. Van Gogh wrote in 1880 that he was copying the plates to gain better control of form. These practices weren’t fashionable—they were foundational.

Why Copying the Masters Still Works

Copying the works of Old Masters remains one of the most effective ways to train the eye. By replicating another artist’s drawing or painting, you begin to understand how they saw the world and what choices they made in depicting it.

Museums like the Louvre and the Prado long allowed students to set up easels and copy masterpieces. In the 1800s, young artists spent months reproducing paintings by Raphael or Titian. This wasn’t mimicry—it was education. By studying every brushstroke, they trained their own vision.

Even today, copying works by artists like Ingres, Dürer, or Rubens can reveal insights about anatomy, design, and composition. This practice builds an inner library of visual knowledge, which can later be applied to original work.

Copying teaches humility and attentiveness. It’s not about originality—it’s about developing the discipline to see as others saw, and to learn from centuries of accumulated wisdom.

Nature Drawing and Observational Discipline

Nature offers one of the most complex and rewarding environments for observation. Drawing from nature—whether it’s trees, animals, or clouds—demands patience and attentiveness. Unlike studio work, where the subject remains still and lighting is controlled, nature is dynamic. Capturing it requires adaptability, sharp focus, and a clear eye for structure.

Artists have long ventured outdoors to study nature firsthand. From Albrecht Dürer’s famous Young Hare (1502) to the field journals of naturalists like John James Audubon in the 1800s, the tradition of observing and recording the natural world by hand is a venerable one. Audubon, for instance, spent decades drawing birds in exacting detail, with over 400 species documented in The Birds of America (1827–1838). His success depended on the keenest observation and the discipline to render what he saw with fidelity.

Field drawing pushes the artist to make quick but accurate decisions. The way light moves through leaves, the shifting position of a bird, or the texture of rock formations—all of these provide visual challenges that sharpen the eye. The goal isn’t a perfect picture, but a true record of what is observed in that moment.

This kind of work doesn’t only improve drawing—it hones real-world visual acuity. Those who practice nature drawing often find themselves noticing more in their everyday surroundings: the way tree branches divide, the structure of feathers, the shadow cast by a leaf. The more one draws nature, the more one sees it with respect and clarity.

Tracking Movement in Wildlife Studies

Wildlife drawing, particularly from life, is a test of both speed and precision. Animals don’t pose—they move. This forces the artist to develop memory, rhythm, and anticipation. Observing an animal closely over time also teaches behavior, posture, and mood—all of which can be captured visually.

Illustrators like Sir Edwin Landseer, who painted animals in the 19th century with great empathy and technical skill, spent countless hours observing them in motion. His famous works like The Monarch of the Glen (1851) show a deep understanding of the anatomy and spirit of his subjects. That insight came from watching, sketching, and learning over time.

When drawing animals, artists often make rapid thumbnail sketches to capture motion. These quick studies help train the eye to find the essence of movement without getting lost in minor details. Over time, this leads to better recall and swifter accuracy.

Such observational skills have applications beyond art. Naturalists, veterinarians, and even hunters benefit from being able to detect subtle changes in animal behavior. Drawing from life sharpens those instincts, teaching patience and respect for the subject.

Botanical Drawing for Detail Awareness

Botanical illustration is one of the oldest forms of scientific art, dating back to the herbal manuscripts of Ancient Greece. By the Renaissance, artists like Leonardo da Vinci and later Maria Sibylla Merian in the late 1600s were producing studies of plants with meticulous precision. These works demanded not only artistic skill, but extraordinary observational clarity.

Drawing plants teaches the artist to see structure: stem, node, leaf vein, petal symmetry. Unlike animals, plants don’t move, but their details are often minute and complex. Every fold, curve, and gradient has purpose and variation. Botanical drawing cultivates the discipline to notice and render these faithfully.

Modern botanical artists like Anne-Marie Evans and Pandora Sellars have continued this tradition, producing works that are both beautiful and scientifically valuable. Their drawings are often used in botanical identification and classification. The accuracy required is exacting and humbling.

Studying plant forms helps train a steady hand and a patient mind. Drawing even a single leaf with full attention reveals patterns and rhythms otherwise missed. This reinforces not just better seeing, but a deeper appreciation for the intricacy of creation.

- Field Drawing Tools for On-the-Go Observation

- Pocket-sized sketchbook with hard cover

- 2B and 4B pencils or a mechanical pencil

- Kneaded eraser and portable sharpener

- Lightweight folding stool or mat

- Viewfinder frame to isolate compositions

The Role of Memory in Artistic Observation

Observation doesn’t stop at seeing—it extends into memory. Drawing from memory challenges the brain to recall and reconstruct visual information. This develops visual memory, spatial awareness, and long-term attention. The process pushes the artist to think not only about what was seen, but how it was understood.

Classical training often involved memory drawing. After a period of intense observation, students would be asked to step away and recreate what they saw from memory. This revealed the limits of their perception and reinforced the need to observe more carefully in the future.

Visual memory is especially important in professions like architecture, law enforcement, and even military strategy. The ability to retain and recall details accurately can influence major decisions. Artists who practice memory drawing enhance this skill dramatically over time.

Additionally, drawing from memory helps identify what the brain prioritizes. You begin to understand which shapes, shadows, or angles stood out to you—and which were missed. Over time, this trains a keener sense of what matters visually and how to capture it effectively.

Sketching from Memory vs. Life

Comparing a drawing done from life to one done from memory is a useful way to measure observational growth. The memory drawing typically reveals distortions, simplifications, or omissions that highlight where perception broke down. But with practice, the gap narrows.

Many ateliers encourage this practice. For example, students may spend an hour drawing a cast or live model, then return to the studio the next day to recreate it from memory. It’s humbling, but illuminating. The brain learns to hold onto more visual information over time.

Historical artists also employed this technique. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a master of portraiture in the early 19th century, often relied on strong visual memory when retouching works or drawing sitters who were not present. His memory was not innate—it was trained.

Practicing this way develops not only sharper memory but better visualization. You begin to think in images, not just in words, and that supports stronger planning, spatial reasoning, and design.

The Role of Repetition in Recall

Repetition is central to memory development. The more often you observe and draw a subject, the more ingrained its visual characteristics become. Repeated study of similar forms—like the human skull or a tree in different seasons—builds a reliable internal visual library.

This method was famously used by George Bridgman, a Canadian-American art teacher at the Art Students League in New York in the early 20th century. His repetitive drawing exercises helped students internalize the structure of the human figure. His books remain widely used in figure drawing education.

Memory recall isn’t about perfect replication. It’s about learning to understand and retain structure, movement, and proportion. Repetition teaches the brain which features to focus on and how to internalize relationships between parts.

Memory drawing also fosters independence. Once the artist no longer needs a reference to recall basic forms, their creative and compositional options increase. This is not only useful for artists but for anyone needing to develop mental clarity and retention.

Integrating Art into Education and Daily Life

Observation is not an elite skill—it can and should be nurtured in every household and school. When children and adults are encouraged to draw, look closely at objects, and appreciate detail, they become more attentive, respectful, and mentally disciplined. Art offers a natural platform for this training.

Traditional education emphasized drawing as a fundamental skill. In 19th-century America and Europe, even public schools taught basic sketching and object study. These exercises were seen as essential to forming a balanced intellect. That perspective has faded in recent decades but remains valuable.

Incorporating art into daily routines—whether through drawing, museum visits, or close-looking games—can reshape how families think and observe. A simple weekly habit of drawing everyday objects can yield remarkable improvements in focus and patience. Observation becomes a shared value.

Art can also build community. Group sketching sessions, collaborative mural projects, or observational games develop not only visual skill but interpersonal connection. In a time when many interactions are digital and fragmented, art brings people together in shared attention and presence.

Teaching Children to Observe Through Art

Children are natural observers. They’re constantly discovering the world through touch, sight, and movement. Art activities help channel that energy into focused attention. Simple exercises like copying shapes, noticing color differences, or drawing from memory teach patience and critical thinking.

Many educators today are rediscovering the power of drawing to teach non-art subjects. Math, science, and geography all benefit from visual exercises. Drawing a leaf helps a child understand biology; sketching a map sharpens spatial reasoning. These interdisciplinary methods build stronger minds.

Using art to teach observation also helps children develop self-control. They learn to sit still, look carefully, and accept mistakes. This cultivates perseverance, humility, and focus—virtues too often overlooked in modern education.

Parents can encourage this by setting aside “quiet seeing time” or art observation walks. Children naturally rise to the challenge when given the space to explore and the encouragement to observe closely.

Using Art at Work to Improve Decision-Making

In the workplace, observation is often the key to problem-solving. Missed details can lead to costly errors, while careful visual attention can reveal opportunities or hazards. Incorporating art into training programs or team-building exercises strengthens this faculty.

Some companies now use drawing workshops as part of leadership training. These are not about producing art but about improving visual awareness and communication. Participants learn to describe what they see clearly, think spatially, and approach problems with calm attention.

Even simple practices like keeping a visual journal of project stages or sketching rough workflows can enhance clarity. These habits don’t require artistic ability—just commitment to seeing more precisely.

In a world increasingly dominated by screens and fast decision-making, those who cultivate visual discipline through art gain a distinct advantage. They become better planners, better listeners, and more deliberate thinkers.

Developing a Lifelong Practice of Seeing

Observation is not something you master in a weekend class. It’s a lifelong practice that deepens with time, much like prayer, reading Scripture, or craftsmanship. Through repeated engagement with drawing, art appreciation, and sketching, the mind becomes more attuned to its surroundings. Seeing becomes a habit, not just a task.

People who train their observation through art begin to approach the world differently. They notice the rhythm of footsteps, the way light filters through tree leaves, and the subtle expressions that flash across faces. This level of attentiveness nurtures both intellect and character. It’s a form of mental stewardship—treating what one sees with the respect it deserves.

Artists from history understood this well. Leonardo da Vinci, who lived from 1452 to 1519, once wrote that the average man looks without seeing. His journals reveal a mind obsessed with seeing clearly—whether in anatomy, nature, or human interaction. He believed that observation was the foundation of wisdom, not just art.

Carving out time each day to observe and draw—even briefly—reorients the mind. It doesn’t require talent, only intention. Over time, this develops not only stronger artistic skills but deeper personal discipline and understanding.

Seeing as a Moral Discipline

Observation is not just a technical skill—it’s a moral one. When we take the time to truly see something, we give it dignity. Whether it’s a person’s expression or the intricate design of a leaf, careful observation honors the subject. It reflects gratitude and reverence for the created world.

Historically, artists and naturalists believed that to observe was to respect. John Ruskin, writing in the mid-19th century, argued that drawing taught moral clarity. By taking the time to see something rightly, he believed, people would also learn to judge rightly. This idea resonates in a time when shallow judgments and quick takes often dominate public discourse.

Paying attention isn’t always easy. It demands humility and restraint—virtues that art practice develops over time. As with any form of discipline, the benefits come slowly but endure.

When we observe carefully, we also become better neighbors, parents, and citizens. We listen more, jump to conclusions less, and live with a greater awareness of truth and beauty.

Making Visual Practice a Daily Habit

To make observation a daily habit, one doesn’t need an art studio or expensive tools. A pencil and a notebook are enough. The key is to set aside time regularly—ten to twenty minutes a day—to draw, study, or reflect visually. Like any habit, consistency is more important than intensity.

Start small: draw your coffee mug, a window view, or your hand. Practice looking, not assuming. Over time, you’ll notice your mind sharpening, your memory improving, and your surroundings becoming more vivid.

Many people also find benefit in pairing drawing with other disciplines—reading Scripture, journaling, or walking. Visual practice complements reflection, deepens prayer, and fosters gratitude. It’s a grounding habit in an unsteady world.

Ultimately, observation through art becomes a way of life. It helps people live more attentively, think more clearly, and act with greater integrity. That kind of vision—literal and metaphorical—is sorely needed today.

Key Takeaways

- Drawing, sketching, and art appreciation are effective tools for improving observation skills in both children and adults.

- Classical methods like sight-size drawing and Bargue plates emphasize accuracy and build disciplined visual habits.

- Nature drawing develops patience and sensitivity to detail, especially when working with live or changing subjects.

- Observational drawing from memory enhances visual recall, spatial understanding, and mental clarity.

- Incorporating art into education and daily life strengthens focus, sharpens judgment, and encourages moral attentiveness.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can anyone improve their observation skills through art, or is it only for “artistic” people?

Anyone can improve with practice. Observation is a skill, not a talent. - What’s the best way to start building observation skills at home?

Begin with ten minutes of sketching daily and focus on simple objects like cups, hands, or plants. - Is classical drawing training still relevant today?

Absolutely. The precision and discipline it fosters are timeless and adaptable across many fields. - How is drawing from life different from drawing from photos?

Life drawing engages depth, movement, and light more realistically, forcing the artist to see more clearly. - Does art appreciation help even if I don’t make art myself?

Yes—studying artworks teaches visual analysis and builds patience, critical thinking, and awareness.