Wassily Kandinsky is often celebrated as the pioneer of abstract art, but there’s far more to his paintings than swirls of color and geometry. Beneath the surface of his canvases lies a hidden system of symbols, codes, and spiritual allusions. For Kandinsky, painting wasn’t just about form or color—it was a form of visual language, meant to awaken the viewer’s inner world. His abstract works are deeply infused with ideas from mysticism, religion, music, and personal vision, creating a symbolic universe that demands close interpretation.

Born in 1866 in Moscow and raised during a time of rapid industrial and intellectual change, Kandinsky saw art as a tool for spiritual revival. He wasn’t merely reacting to external trends; he was building an inner world. His artistic revolution began with an inner revolution, one influenced by his belief that visual symbols could speak directly to the soul. With an eye for nuance and a hand guided by faith and intuition, Kandinsky created a new visual language—one designed not just to be seen, but to be felt and interpreted.

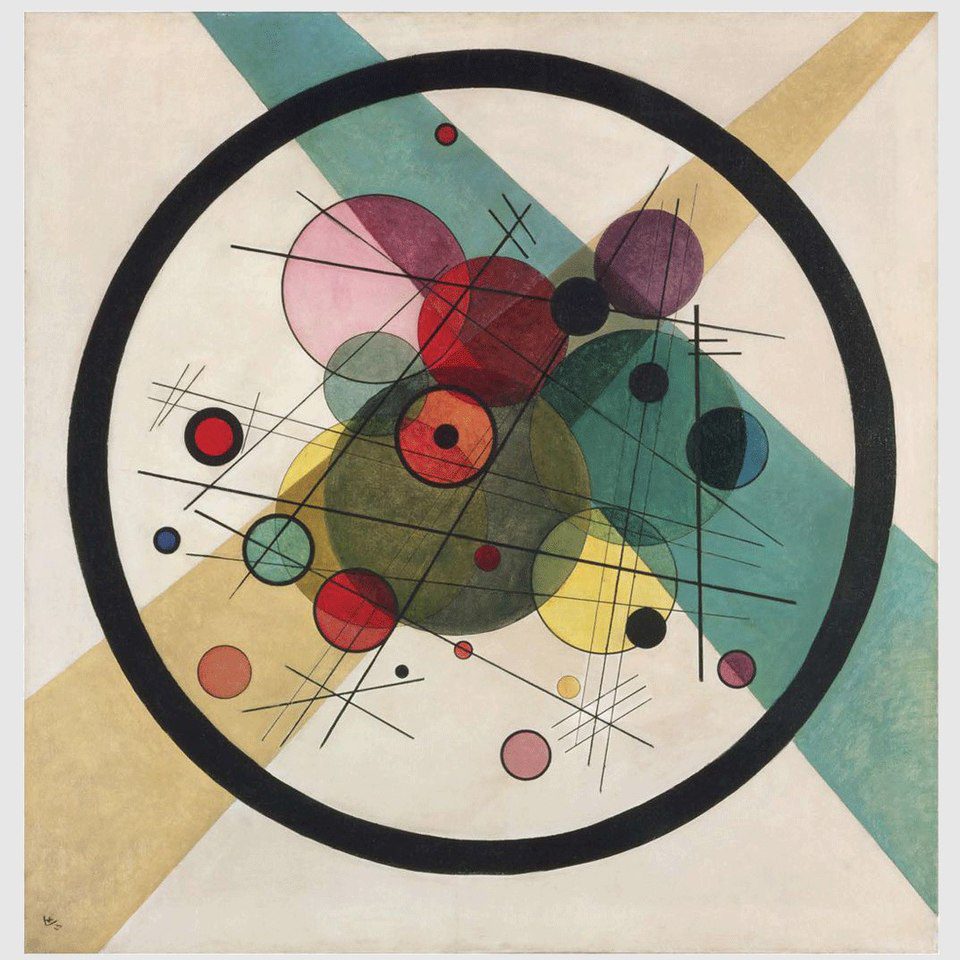

When you look at a Kandinsky painting, it might initially seem chaotic or arbitrary. But look closer, and you’ll find a coherent grammar of signs: circles, triangles, lines, arcs, and carefully chosen colors. Each of these elements had purpose. Whether acting as spiritual metaphors or musical references, Kandinsky’s symbols reveal a painter with a profound commitment to communicating meaning beyond the visible.

To understand his art fully, it’s essential to dig into the symbols he used and the influences that shaped them. From his Russian Orthodox roots to his involvement with the Bauhaus and Theosophy, Kandinsky’s paintings serve as encrypted messages—a kind of visual symphony layered with secret motifs, waiting to be heard by those who know how to listen.

Kandinsky’s Spiritual Foundation

Kandinsky believed deeply in the spiritual role of the artist. This belief was central to his life and work and was formally expressed in his groundbreaking essay Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), published in 1911. In it, he proposed that true art must come from an “inner necessity” and that form and color should express spiritual truths. The essay laid out a spiritual framework for abstraction and remains one of the most important theoretical texts in modern art.

Kandinsky was strongly influenced by Theosophy, a spiritual movement that attempted to unify all religions and sciences. Founded by Helena Blavatsky in the late 19th century, Theosophy taught that symbols, geometry, and color had deep, universal meaning. Kandinsky absorbed these ideas, integrating them into his approach to painting. He believed that certain visual forms had the power to access higher spiritual realms.

His Russian upbringing also played a crucial role in his symbolic vision. Icons from the Russian Orthodox Church, with their rich color symbolism and spiritual intensity, left a lasting impression on him. He would later reflect on seeing a Russian icon at a church as a child and being overwhelmed not just by its beauty but by its power—a sacred object that stirred something inside him. That early experience would echo through his career as he pursued an art that was both visionary and transcendent.

Another influence was synesthesia, the neurological condition where senses overlap—for example, seeing colors when hearing music. Whether or not Kandinsky had clinical synesthesia has been debated, but he frequently described experiencing sounds in color and vice versa. This sensory crossover became a spiritual tool for him, a way to connect the visual and the auditory into a single symbolic system.

The Language of Color

For Kandinsky, color was never neutral. Each hue had a psychological and spiritual character, one that could affect the viewer’s soul directly. He didn’t just use color for aesthetic pleasure; he used it with intention, constructing a symbolic color language that served as the emotional foundation of his works. His theories about color are elaborated in his 1912 book On the Spiritual in Art, where he argued that colors possess an inner sound and emotional tone.

He considered blue to be the most spiritual of all colors, capable of pulling the soul upward toward infinity. A deep, dark blue symbolized the “deepening calm” of the spiritual world, while lighter blues could feel more like the expansive sky. Yellow, on the other hand, represented the earthly, the aggressive, even the annoying. He wrote that yellow “hurts the eye” and considered it to have a violent, unsettling energy when not balanced.

Red was associated with strength and vitality—a color that demanded attention but could also be uplifting. Green served as a symbol of balance and stability, though he viewed it as less spiritually charged than blue or red. For Kandinsky, combinations of colors weren’t just for harmony or contrast; they were like chords in music, creating emotional resonance through their relationships.

This symbolic use of color shows up throughout his major works. In Improvisation 28 (Second Version) from 1912, sharp contrasts of red, yellow, and blue punctuate swirling forms and evoke not just visual excitement but emotional turmoil. These aren’t random choices. Each color combination is deliberate, meant to stir something unspoken in the viewer—an inner reaction that mirrors the artist’s own.

Geometric Forms as Esoteric Code

Beyond color, Kandinsky developed a visual vocabulary of shapes and forms that carried specific symbolic meanings. Circles, triangles, lines, and curves weren’t simply compositional elements—they were esoteric signs meant to communicate abstract concepts. These geometric shapes functioned as a secret code, each one chosen for its spiritual resonance and expressive power.

The circle, one of Kandinsky’s most frequently used forms, represented the spiritual self and cosmic unity. He described it as “the most peaceful shape” and associated it with the eternal, the divine, and the unchanging. You’ll find circles in many of his later works, such as Several Circles (1926), where overlapping rings float in a black void like celestial bodies in a mystical universe.

Triangles were also vital, often pointing upward to symbolize aspiration, growth, or spiritual striving. Kandinsky used triangles to create a sense of upward movement and energetic tension. In some compositions, sharp-angled triangles form the visual equivalent of musical crescendo, pushing the viewer’s gaze upward and outward. The triangle’s stability and dynamism made it ideal for conveying spiritual ascent.

Lines, both straight and curved, were used with precision and intent. A diagonal line could suggest conflict or dynamic energy, while a horizontal line might signal rest or stillness. Curved lines added rhythm and flow, often suggesting musical motion or spiritual fluidity. Kandinsky’s approach to line wasn’t just theoretical; it was practical and consistent, showing up in works across decades.

These symbols weren’t random. He developed a personal system that echoed the mystic diagrams found in both Eastern mandalas and Western alchemical texts. Whether he was painting a circle in blue or layering triangles in complex formations, each choice carried a coded message intended for those who could read it—not with the eyes, but with the soul.

Synesthesia and Hidden Musical Symbols

Kandinsky’s belief that painting could be like music wasn’t metaphorical—it was rooted in his own sensory experience. He often described hearing colors and seeing sounds, which he attributed to synesthesia. Although the clinical diagnosis of synesthesia remains uncertain in his case, his writings and art reveal a deep connection between sound and vision. This crossover became a defining trait of his symbolic approach to art.

Music was more than inspiration—it was a structural model. Kandinsky named many of his paintings as if they were musical pieces. Works such as Composition VII (1913) and Improvisation 31 (Sea Battle) (1913) don’t depict traditional subjects; they function like visual symphonies, expressing inner states and spiritual battles through rhythm, form, and tone. Each line and color operates like a note or chord, building toward visual harmony or dissonance.

In Composition VII, often called his most complex work, he uses a swirling composition to suggest not only movement but orchestration. The painting contains references to resurrection, flood, and spiritual rebirth, but they’re rendered in abstract forms that flow like musical motifs. This work was created in just four days in November 1913, but it was preceded by nearly 30 preparatory studies—proof of how intentional his symbolism truly was.

Kandinsky was also influenced by contemporary composers like Arnold Schoenberg, whose atonal music broke free from classical structures—much like Kandinsky’s paintings abandoned traditional subject matter. Their correspondence in the early 1910s reveals a shared vision of an art form that transcended genre. For Kandinsky, embedding musical structure into visual form was not only possible but essential for awakening higher consciousness.

Letters and Numbers: Occult or Orderly?

Kandinsky’s system of naming his works often raises questions. He grouped many of his paintings into three main series: Compositions, Improvisations, and Impressions. These weren’t arbitrary titles; they reflected a hierarchy of inner expression. Impressions were based on real-world experiences interpreted through emotion. Improvisations came from spontaneous inner visions. Compositions were the most deliberate—intellectually planned like symphonies.

The numbered titles within these series might seem cold or mechanical at first glance, but they reflect a structured, symbolic intention. For instance, Composition V (1911) was rejected by a Munich art exhibition jury for being too radical, yet Kandinsky saw it as a critical step in his spiritual evolution. The numbering may represent stages in his artistic or spiritual journey, each one building on the last.

Some scholars interpret the numbers almost like chapters in a mystical text. Much like musical symphonies are numbered, Kandinsky’s paintings reflect progress and cohesion. The absence of descriptive titles removes distraction, allowing the viewer to focus entirely on form, color, and spiritual resonance.

There’s also speculation that this system had occult undertones. Kandinsky was familiar with numerology and mystical philosophies that assigned symbolic meanings to numbers. Whether intentional or intuitive, his naming system underscores the hidden structure behind his abstract art—a structure that reveals itself only to those willing to look beyond the surface.

The Influence of Russian Folk Art and Icons

Kandinsky’s deep Russian roots had a profound influence on his symbolic language. Although he spent much of his career in Germany and France, his earliest aesthetic memories were shaped by Russian Orthodox churches, folk traditions, and fairy tales. He once recalled visiting the Kremlin as a child and being overwhelmed by the brilliance of the colors and the power of the icons—not for their religious narrative, but for their sheer spiritual impact.

The decorative and symbolic nature of Russian icon painting left a lasting mark. Icons were not mere illustrations of biblical events; they were windows into the divine, saturated with symbolic gestures, halos, and deliberate use of gold leaf to suggest the otherworldly. Kandinsky absorbed this tradition of symbolic representation early in life and brought it with him into abstraction, where symbols took the place of saints and spiritual forms.

Russian folk art, too, contributed to Kandinsky’s symbolic repertoire. Vibrant patterns, stylized figures, and repetitive motifs found in textiles, painted dishes, and peasant crafts likely influenced his embrace of geometry and strong color contrasts. These elements made their way into his early figurative work and subtly persisted even after he transitioned into abstraction after 1911.

Even as Kandinsky left behind literal subjects, his spiritual connection to his homeland remained encoded in his works. Paintings like Improvisation 9 (1910) or Moscow I (1916) include stylized domes, towers, and landscape references that suggest a lingering affection for the Russian visual lexicon. The presence of these motifs isn’t nostalgic; it’s symbolic. Kandinsky didn’t seek to reproduce Russia—he sought to distill its spiritual essence into forms the viewer could feel more than recognize.

Kandinsky and the Bauhaus: Symbols Go Systematic

When Kandinsky joined the Bauhaus school in 1922 at the invitation of Walter Gropius, his symbolic system became more methodical and refined. The Bauhaus was dedicated to uniting art, craft, and design into a coherent philosophy, and Kandinsky found in it a platform to teach and evolve his visual language. His tenure at the school—first in Weimar and later in Dessau—lasted until its closure by the Nazis in 1933.

During this period, Kandinsky began to codify his symbolic vocabulary through both painting and pedagogy. He developed what he called “point and line to plane” theory, eventually published in his 1926 book Point and Line to Plane. In it, he laid out a structured analysis of how visual elements like points, lines, and shapes interact to create meaning, much like grammar in language. This theory became the foundation of his Bauhaus teachings and influenced generations of designers and artists.

His Bauhaus-era paintings, such as Composition VIII (1923) and Yellow-Red-Blue (1925), display a high degree of geometric clarity. These works are filled with intersecting lines, calibrated curves, and strategic placements of color and shape. The visual chaos of his earlier Improvisations gave way to a controlled system where each form had a measured role. Yet the spiritual content remained—the symbols were simply distilled and systematized.

What distinguished Kandinsky’s Bauhaus work from other modernist abstraction was his insistence on metaphysical meaning. While fellow Bauhaus faculty like Paul Klee also explored color and form, Kandinsky’s work retained a uniquely spiritual agenda. Every lesson, every diagram, every line was meant to reveal deeper truths—not just about aesthetics, but about human consciousness and its connection to the unseen world.

Decoding Specific Works

While Kandinsky’s entire oeuvre is rich with symbolic meaning, certain paintings stand out as prime examples of his esoteric system in action. One of the most notable is Composition VIII, painted in 1923 during his Bauhaus years. This work features a dense field of geometric shapes—circles, triangles, lines—arranged in a way that feels at once chaotic and harmonious. It’s been called a visual fugue, reflecting his desire to translate musical structure into painting.

In Composition VIII, circles dominate the space, symbolizing spiritual wholeness and cosmic unity. Diagonal lines slice across the canvas, introducing dynamic tension and suggesting motion or struggle. Meanwhile, Kandinsky uses primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—not just for balance but for their emotional and spiritual resonance. The piece is a meditation on order and chaos, rhythm and structure.

Yellow-Red-Blue (1925) is another key work. Here, three large colored zones dominate the canvas, each representing a spiritual force: yellow as warmth and instability, red as vitality and energy, and blue as depth and tranquility. These forces are not just symbolic but relational—Kandinsky arranges them in opposition and dialogue, using abstract forms to convey a dynamic spiritual struggle.

Earlier works like Composition VII (1913) reflect a more intuitive and spontaneous form of symbolism. This massive, swirling canvas includes faint references to resurrection, the flood, and apocalypse—biblical themes rendered in abstract motion. Kandinsky described it as the “most complex piece” he ever painted, and indeed, it was preceded by numerous studies and sketches. Its symbolic layers are rich and open-ended, designed to provoke emotional and spiritual response.

Criticisms and Alternate Interpretations

While Kandinsky’s symbolic approach has earned him enduring acclaim, it hasn’t been without critics. Some scholars and art historians argue that his symbolism is too personal, too esoteric, or even too opaque to be useful. Abstract art, they say, often defies consistent interpretation, and Kandinsky’s spiritual frameworks can come off as dogmatic or overly mystical to modern audiences.

Others point out that Kandinsky’s reliance on subjective experience makes his symbolism hard to verify or reproduce. Unlike religious iconography or classical allegory, which have widely recognized meanings, Kandinsky’s symbols depend heavily on his own worldview. This has led some critics to dismiss them as arbitrary or even as artistic posturing.

Still, defenders argue that this very subjectivity is what gives Kandinsky’s work its power. By inviting the viewer into a personal, emotional, and spiritual dialogue, his art transcends linguistic and cultural boundaries. The lack of fixed meaning becomes a feature, not a flaw. His paintings are not puzzles to be solved but experiences to be felt—each viewer brings their own soul into the interpretive process.

Academic debate aside, it’s clear that Kandinsky’s symbolic system influenced a wide range of movements, from Abstract Expressionism to Color Field painting. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and even contemporary digital artists owe a debt to his vision. Whether one believes in his symbols or not, they continue to shape how we see—and feel—abstract art today.

Why Kandinsky’s Symbols Still Matter

Nearly a century after his death in 1944, Wassily Kandinsky’s symbolic language remains relevant and inspiring. In a world increasingly dominated by surface-level imagery and digital saturation, his insistence on deeper spiritual meaning feels more vital than ever. Kandinsky reminds us that art can—and should—speak to the soul, not just the eye.

His influence extends beyond the world of painting. Designers, architects, musicians, and filmmakers have drawn from his symbolic system to create works that aim to touch something transcendent. His writings continue to be taught in art schools and are studied alongside those of other visionaries like Paul Klee and Kazimir Malevich.

What makes his symbols endure is their emotional and spiritual authenticity. Kandinsky wasn’t chasing trends or trying to shock; he was searching for eternal truths. His shapes and colors, while abstract, are deeply human. They speak to inner states we all recognize—hope, tension, peace, struggle—even if we can’t always name them.

By learning to read Kandinsky’s visual language, we gain more than an appreciation of one artist’s work. We rediscover art as a sacred practice, one capable of revealing the invisible and awakening the spirit. That’s why his symbols still matter. They’re not just hidden—they’re waiting to be discovered.

Key Takeaways

- Kandinsky’s art is filled with hidden spiritual symbols, drawn from Theosophy, music, and Russian religious tradition.

- His use of color was deeply intentional, with each hue carrying specific emotional and metaphysical meaning.

- Shapes like circles and triangles were used systematically to express cosmic ideas and inner states.

- Works like Composition VIII and Yellow-Red-Blue showcase his symbolic system in highly refined form.

- Despite some criticism, Kandinsky’s influence on modern and abstract art remains profound and enduring.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the meaning behind Kandinsky’s use of circles?

Circles often represented spiritual wholeness, the eternal, and unity in Kandinsky’s symbolic system. - Did Kandinsky really experience synesthesia?

While not medically confirmed, Kandinsky described vivid cross-sensory experiences that strongly influenced his work. - Why did Kandinsky number his paintings?

Numbering reflected a spiritual and formal progression, particularly in his Composition, Improvisation, and Impression series. - Was Kandinsky part of any religious movement?

He was heavily influenced by Theosophy and mysticism but did not belong to a formal religious sect in his adult years. - How did the Bauhaus influence Kandinsky’s symbols?

At the Bauhaus, Kandinsky refined and codified his symbolic system into structured theories involving geometry and form.