The Roman Empire is rightly known for its military might, precision, and discipline. But inside the utilitarian stone and timber barracks of its soldiers, something else survived—art. Wall paintings found in Roman military forts across the empire reveal a surprising layer of culture and psychology behind the martial façade. These murals were more than just decoration. They served spiritual, symbolic, and even emotional roles for soldiers stationed in remote and often hostile corners of the empire.

From Britain’s wind-swept northern border to the desert fortresses of Syria, these wall paintings give modern viewers a glimpse into the world Roman legionaries built for themselves. With scenes of gods, imperial symbols, and decorative patterns, these artworks reinforced Roman identity, boosted morale, and expressed the ideals of order and power. Archaeological discoveries at Vindolanda, Dura-Europos, Lambaesis, and other forts have opened a new window into how Rome’s soldiers saw themselves—and how they wanted to be seen.

Art Behind the Shield: Purpose and Meaning of Roman Military Wall Paintings

Military Morale and Identity in Visual Form

Roman military life was harsh, repetitive, and often isolated. The wall paintings found in barracks and principia (headquarters buildings) helped create a structured, familiar environment that reinforced Roman values. Paintings of deities like Mars, the god of war, or Victoria, the goddess of victory, reminded soldiers of their divine favor and the strength of Rome’s mission. Scenes of battles, triumphal processions, or idealized Roman architecture provided a constant visual reminder of the empire’s grandeur and order.

These visual elements contributed directly to military cohesion. In an age without modern flags or printed manuals, painted walls could serve as symbolic representations of the empire and its ideals. The repetition of specific motifs—like eagles, standards, and divine figures—established continuity across garrisons, from Britain to the Danube. Soldiers moved from fort to fort, but the imagery remained familiar, reminding them that they were part of something vast and unified.

Decoration or Propaganda?

It’s tempting to dismiss Roman military wall paintings as simple decoration, but their content shows deliberate ideological messaging. Much like public monuments in Rome itself, these artworks often included motifs designed to project power, order, and Roman superiority—not just to soldiers, but to any local allies or subjugated populations who entered the forts. Scenes could evoke imperial power, military discipline, and the gods’ favor on Roman arms.

Unlike in civilian homes—like those at Pompeii or Herculaneum—where murals often depicted leisure, mythology, or romantic themes, military wall paintings leaned toward the austere and idealistic. For instance, while Pompeian frescoes frequently show Bacchic revelry or romantic trysts, the art in military contexts typically centered on discipline, piety, and martial valor. These differences underline the function of the barracks: not as places of retreat, but as instruments of state control and ideological reinforcement.

Religious and Mythological Symbols in Barracks Art

Religion played a central role in Roman military life, and wall paintings served as daily reminders of the spiritual structure supporting the empire. Murals often featured the lares (household gods), genii (guardian spirits), and personifications of virtues like Virtus and Disciplina. Mars was a common figure, naturally, but so was Jupiter—the king of the gods—often depicted wielding thunderbolts or seated on a throne, signifying divine order backing Roman authority.

Shrines within the forts—called aedes—were regularly decorated with such imagery. The famous painted altars at Vindolanda, for instance, show stylized gods, standard-bearers, and military insignia in vivid red, black, and yellow pigments. These images weren’t just symbols; they were active tools in the soldiers’ religious life. Daily rituals and offerings were performed in their presence, reaffirming loyalty both to Rome and to the gods that guarded it.

Types of themes commonly found in military paintings:

- Battle scenes and martial processions

- Mythological figures like Mars, Victory, or Hercules

- Imperial symbols (e.g., the eagle, standards, emperors)

- Architectural motifs framing religious or ideological content

Technique and Style: How Roman Soldiers Painted Their Walls

Fresco Techniques Adapted to Military Life

Roman wall painting followed certain standardized techniques, the most prominent being buon fresco, in which pigment is applied to wet plaster, allowing the color to bind with the wall. This method was durable and favored in permanent stone structures. However, in many military settings—especially in timber or semi-permanent barracks—fresco secco (dry painting) was more practical, since it allowed for faster application and could be touched up more easily.

Military forts were often built quickly and in hostile climates. In northern Britain or along the German frontier, damp conditions made true fresco challenging. Evidence from Vindolanda, dated to the early 3rd century AD, shows that many of the painted surfaces were on thin wooden panels or plastered walls coated with limewash. Pigments like red ochre, carbon black, and yellow orpiment were commonly used, applied in geometric patterns, border designs, or figural scenes.

Color, Composition, and Style in Fort Decorations

Despite the limited materials available in remote garrisons, Roman military painters created visually striking environments. The most common color scheme included deep red (cinabrium), black, white, and earth-toned yellows. These were often laid out in rectangular panels with framing bands—imitating architectural structures like columns or niches. This created an illusion of order and space within the confined interiors of barracks.

Compositionally, the paintings followed the Roman preference for symmetry and structure. Figures were centered and balanced, with scenes often divided into three horizontal registers. In more elaborate murals—like those at Dura-Europos, dating to the mid-3rd century AD—soldiers are shown in battle formation, with banners and mounted officers surrounded by symbols of divine favor. Even in simpler garrisons, the same artistic logic applied: symmetry, symbolism, and structure over emotion or realism.

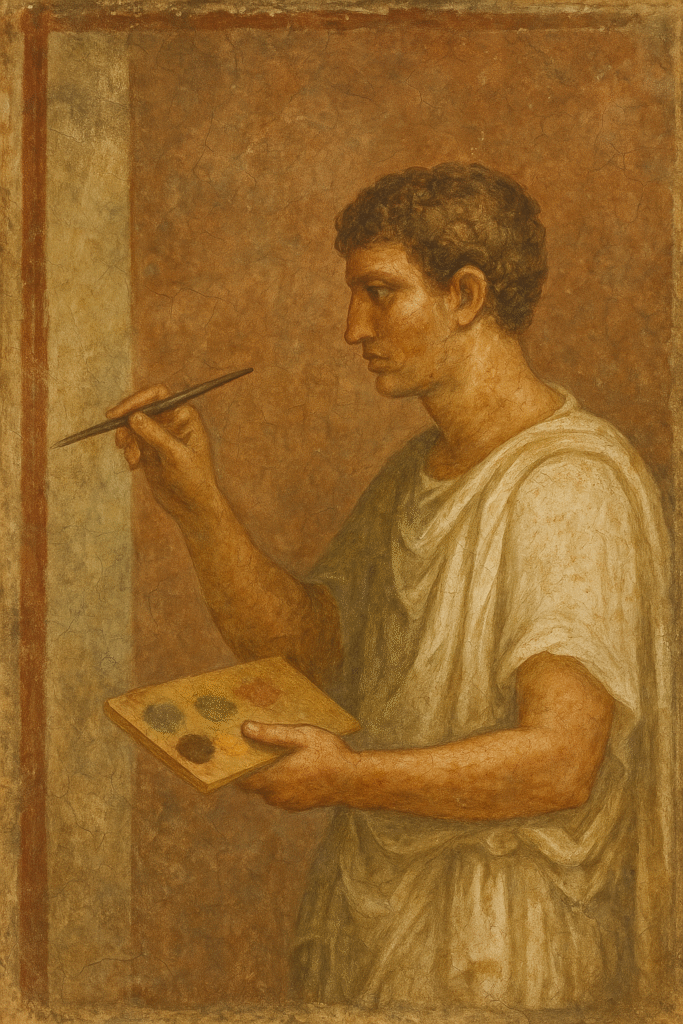

Who Painted These Walls? Legionaries or Professionals?

A key question for scholars has been whether Roman soldiers painted these murals themselves or hired professionals to do the work. In civilian contexts, muralists were often itinerant craftsmen who specialized in wall decoration, but in the military, the answer is less clear. Evidence suggests that traveling artisans—possibly attached to the fabricae (military workshops)—may have been employed at larger forts and permanent installations.

However, there is growing archaeological evidence that some painting was done by the soldiers themselves, particularly in auxiliary forts and frontier stations. At Vindolanda, several stylized and somewhat crude murals suggest the hand of amateur artists rather than trained professionals. Writing tablets recovered from the site, dating to around AD 100, mention men assigned to construction and decoration duties. These soldier-artists likely followed standardized designs, which were disseminated across the army to maintain visual consistency.

Archaeological Evidence: Key Finds from Roman Forts

Vindolanda and Its Painted Panels

Vindolanda, located just south of Hadrian’s Wall in northern Britain, is among the richest sites for Roman military life. The fort was occupied from the late 1st century AD through the 4th century, and excavations have revealed remarkable evidence of wall paintings. In 2003, archaeologists uncovered fragments of painted wooden panels inside a cavalry barracks, dated to approximately AD 105–130.

These panels featured vibrant colors and stylized imagery: a winged Victory figure, military standards, and possibly a representation of a goddess or spirit of the unit. The pigments—mainly red, black, and cream—were preserved thanks to the damp anaerobic conditions of the soil. The paintings show that even in the far north of the empire, military units maintained a visual culture aligned with central Roman ideals. They also suggest that these images were important enough to recreate, even in timber structures likely to be rebuilt every few decades.

Dura-Europos and the Eastern Front

On the eastern edge of the empire, Dura-Europos (in present-day Syria) offers a contrasting but equally revealing set of murals. A Roman garrison was established there around AD 165 and remained active into the 250s. The city was multicultural, and the wall paintings in the military precinct reflect a fusion of Roman, Greek, and local traditions. Scenes in the principia include images of Roman officers flanked by gods, as well as processions and religious rites.

One mural, dated to the mid-3rd century AD, depicts a mounted Roman officer being crowned by Victory while a temple burns in the background—a clear symbol of conquest under divine sanction. This mix of imperial ideology and eastern stylistic influence highlights the adaptive visual language of the Roman military. The paintings also suggest that the spiritual life of the army was deeply embedded in its built environment, especially in border zones where Roman identity had to be asserted more strongly.

Other Sites: Carnuntum, Lambaesis, and Caerleon

Beyond Vindolanda and Dura-Europos, several other forts have yielded important wall painting remains. At Carnuntum in Pannonia (modern Austria), frescoes from a legionary commander’s residence include stylized floral borders and architectural illusions—dating to around AD 200. These suggest a level of domestic comfort and Roman refinement, even in military contexts. Carnuntum was a major base for the Legio XV Apollinaris and served as an administrative center for the region.

In North Africa, the fortress of Lambaesis (Algeria), home to Legio III Augusta, has produced painted plaster fragments with geometric designs and religious symbols, including depictions of Minerva and Hercules. These date from the 2nd to early 3rd centuries AD. Similarly, in Caerleon (Wales), parts of painted walls from the Legio II Augusta fort have been found, including red and white decorative schemes and possible fragments of figural scenes.

Top Roman forts with surviving wall art:

- Vindolanda (Britain)

- Dura-Europos (Syria)

- Lambaesis (North Africa)

- Carnuntum (Pannonia)

- Caerleon (Wales)

Interpreting the Message: What Roman Wall Paintings Reveal About Soldier Life

Reflections of Daily Life and Aspirations

Roman wall paintings in military contexts were aspirational as well as ideological. They reflected what soldiers wanted to believe: that their presence was sanctioned by the gods, that they were participants in a grand civilizing mission, and that order would triumph over chaos. Even in the harshest environments, murals depicting temples, gods, and imperial triumphs brought the ideals of Rome into daily view.

While we don’t find scenes of banquets or family life in military barracks the way we might in civilian homes, there is still a human dimension to this art. The repeated inclusion of protective spirits and religious symbols suggests a need for comfort and divine presence. The act of painting itself may have been a form of psychological relief, giving order and beauty to otherwise utilitarian spaces.

Military Art vs. Civilian Art: Key Differences

Civilian Roman wall painting—especially in the houses of Pompeii and Herculaneum—was often personal, whimsical, and sensual. In contrast, military wall painting was structured, formal, and symbolic. Civilian murals might show mythological love stories, pastoral scenes, or luxurious still lifes. In forts, the content leaned heavily on Roman virtues, discipline, and divine sanction.

This distinction reflects the different purposes of the spaces. Barracks weren’t homes; they were institutions of power, hierarchy, and state ideology. That doesn’t mean they were devoid of aesthetic value—only that their art served a different function. Even the style differed: civilian art often employed softer modeling and atmospheric effects, while military art favored bold outlines, flat colors, and symmetrical design.

Identity, Belonging, and the Roman Worldview

Perhaps the most important function of wall paintings in Roman military forts was to maintain a sense of identity. Soldiers stationed in distant corners of the empire needed to see visual cues that reminded them of Rome, its gods, and its authority. A painted Mars or Jupiter in a cold British barracks served the same role as the Forum in Rome—it anchored the viewer in a shared worldview.

This is why similar artistic motifs appear across forts in Britain, Syria, Africa, and the Danube region. It wasn’t coincidence; it was policy. The military wanted its men to see themselves as Romans first, regardless of where they came from or where they were posted. Art helped forge that identity—not with sentiment, but with symbols, patterns, and sacred imagery that tied every soldier to the eternal order of Rome.

Key Takeaways

- Roman military wall paintings served ideological, religious, and psychological functions, reinforcing Roman identity and morale within forts.

- The artwork typically featured gods like Mars, Jupiter, and Victory, as well as symbols of Roman power, discipline, and structure.

- Techniques included both fresco and secco painting, adapted to local climates and the impermanence of certain structures.

- Major archaeological discoveries at Vindolanda, Dura-Europos, Carnuntum, and Lambaesis provide the best evidence of military wall painting traditions.

- Unlike civilian art, military wall paintings were not decorative luxuries—they were tools of imperial control, unity, and cultural identity.

FAQs

1. Where have Roman military wall paintings been found?

They have been discovered at several key Roman forts, including Vindolanda (Britain), Dura-Europos (Syria), Carnuntum (Austria), Lambaesis (Algeria), and Caerleon (Wales).

2. Were the paintings made by soldiers or professional artists?

Both. Some were painted by itinerant craftsmen working for the army, while others were created by soldiers with artistic skills, especially in more remote or temporary forts.

3. What themes were most common in Roman military art?

Common themes included Roman gods, military standards, personifications of virtues, battle scenes, and symbols of divine favor and imperial power.

4. How did these paintings survive for archaeologists to find?

In many cases, the paintings were preserved by anaerobic soil conditions, rapid collapse, or burial after destruction. Wooden panel paintings at Vindolanda, for instance, survived due to waterlogged conditions.

5. What was the main purpose of the paintings in military contexts?

Their purpose was not merely decorative—they served to maintain morale, reinforce Roman identity, display religious piety, and communicate imperial ideology.