Pareidolia is a psychological phenomenon in which people perceive familiar patterns—such as faces, animals, or objects—in random stimuli. This could be as simple as seeing a face in the clouds, an animal shape in tree bark, or even religious figures in food. The human brain is naturally wired to recognize faces quickly, an evolutionary advantage that helped our ancestors identify allies and threats. This automatic recognition process is so ingrained that our brains often find faces where none actually exist, leading to the artistic and cultural phenomenon of pareidolia.

The history of pareidolia dates back thousands of years, with early humans likely interpreting natural formations as spiritual symbols or omens. Cave paintings from prehistoric times may have been inspired by pareidolic perceptions, where early artists saw forms in rock surfaces and enhanced them with pigment. Across various cultures, pareidolia has influenced mythology, religious experiences, and artistic practices. It is a phenomenon that bridges science, psychology, and artistic creativity, making it a compelling subject for exploration.

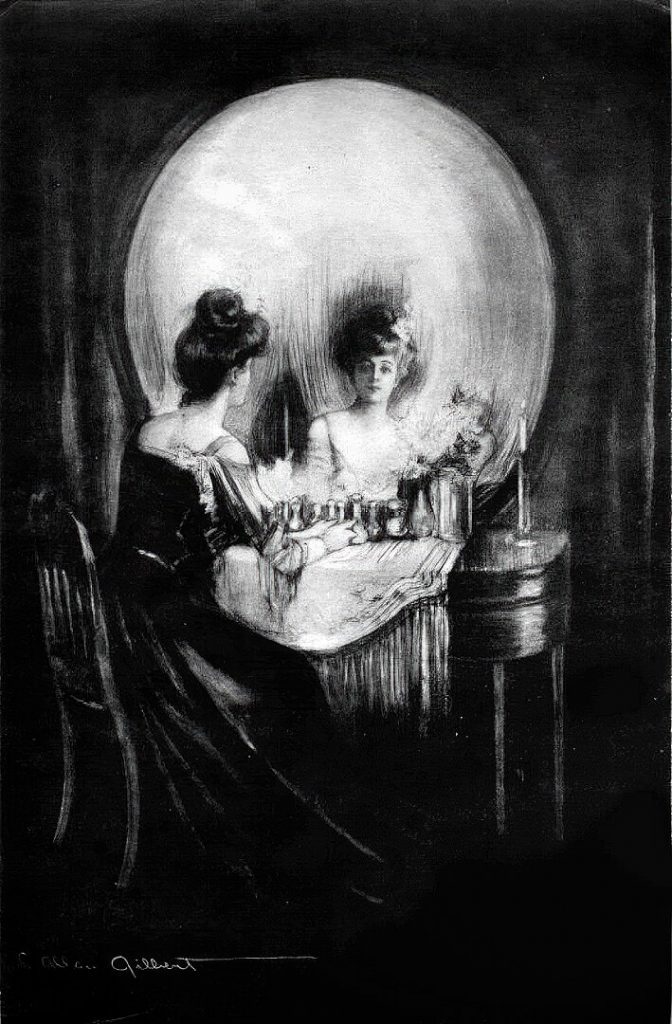

This fascinating tendency extends beyond survival instincts and into creative fields, especially visual art. Artists have long used pareidolia as both a source of inspiration and a deliberate technique to engage viewers. By embedding hidden images or ambiguous forms within their compositions, artists invite multiple interpretations, playing on the viewer’s natural tendency to impose meaning onto abstract shapes.

Modern technology has only amplified our awareness of pareidolia, as digital photography and social media have made it easier than ever to share these intriguing visual occurrences. Viral images of Jesus appearing on toast or a dog’s face in a cup of coffee exemplify how deeply ingrained this pattern recognition is in human perception. Whether intentional or accidental, pareidolia serves as a bridge between reality and imagination, influencing both casual observers and professional artists alike.

The Science Behind Pareidolia: How the Brain Sees What Isn’t There

The brain’s ability to recognize faces so quickly is due to a specialized area called the fusiform face area (FFA), located in the temporal lobe. This region is dedicated to facial recognition, allowing us to identify friends, family, and even detect emotions with just a glance. However, this rapid processing sometimes leads to false positives, where the brain detects a face-like pattern where none exists. This explains why we might see a smiling face in the front of a car or a human-like expression on the surface of the moon.

Pareidolia is closely related to apophenia, the general tendency to perceive meaningful connections in random data. While pareidolia specifically involves visual stimuli, apophenia can extend to auditory and abstract patterns, such as hearing hidden messages in songs played backward. Psychological studies have shown that individual experiences and cultural backgrounds influence how people experience pareidolia. For example, people who frequently engage with religious imagery may be more likely to see divine figures in random textures.

Studies using functional MRI (fMRI) scans have shown that the brain activates similarly when seeing a real face and when experiencing pareidolia. This means that, neurologically, our brains respond to an illusion with nearly the same intensity as they do to an actual person’s face. This finding helps explain why pareidolia can feel so compelling and even emotional for some individuals. The phenomenon is not limited to humans—some research suggests that primates and even certain AI models exhibit pareidolic tendencies.

Technology has begun to mimic and amplify pareidolia through machine learning and neural networks. AI programs designed for facial recognition sometimes identify non-existent faces, much like human brains do. Google’s DeepDream project, launched in 2015, artificially enhances patterns in images to exaggerate pareidolic effects, producing surreal and dreamlike artwork. As artificial intelligence evolves, it raises fascinating questions about perception, creativity, and whether machines can experience pareidolia the way humans do.

Pareidolia in Classical and Renaissance Art

The Renaissance era saw many artists incorporating pareidolia into their works, either intentionally or as a byproduct of creative exploration. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) encouraged artists to look at random textures and stains as inspiration for paintings. He famously wrote about seeing landscapes, faces, and animals in cracked walls and clouds, urging artists to harness these visions for their work. This concept aligns closely with the modern understanding of pareidolia, proving that even centuries ago, artists were aware of and utilizing this phenomenon.

One of the most famous artists associated with pareidolia is Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527–1593), known for his surreal portraits composed of fruits, vegetables, and everyday objects. His works, such as Vertumnus (1591), depict human faces made up of carefully arranged natural elements, tricking the viewer’s perception. Arcimboldo’s paintings rely on the brain’s inclination to group objects into recognizable patterns, making him a pioneer of artistic pareidolia. His art continues to fascinate viewers and influence surrealist artists centuries later.

Religious pareidolia has played a significant role in art history, with many believing divine figures have appeared in natural formations, paintings, and frescoes. The Shroud of Turin, a cloth believed to bear the image of Jesus, is one of the most famous examples. In churches and cathedrals, worshippers have reported seeing the Virgin Mary’s face in tree bark or light reflections, leading to both spiritual reverence and artistic interpretation. Whether seen as divine messages or mere coincidences, these occurrences have inspired countless religious artworks.

The Baroque and Romantic movements also embraced pareidolia in their dramatic and highly detailed compositions. Artists such as Francisco Goya (1746–1828) and William Blake (1757–1827) incorporated shadowy figures and hidden faces within their works to evoke mystery and emotion. Their use of light and darkness often played tricks on the viewer’s mind, enhancing pareidolic perception. By blending realism with illusion, these artists pushed the boundaries of visual storytelling, proving that pareidolia is not just a curiosity but a powerful artistic tool.

Pareidolia in Modern and Contemporary Art

The Surrealist movement of the early 20th century fully embraced pareidolia as a creative technique. Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) was particularly known for embedding hidden images within his dreamlike paintings. Works such as The Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire (1940) force the viewer’s brain to switch between two different interpretations of the same scene. Dalí’s approach to art was deeply influenced by psychology, especially the theories of Sigmund Freud, who explored the unconscious mind’s role in perception.

Another Surrealist painter, René Magritte (1898–1967), often manipulated pareidolic imagery to challenge reality. His 1928 painting The False Mirror depicts an eye with a cloudy sky inside, playing with the way we interpret reflections and faces. Magritte’s work encourages viewers to question their assumptions about vision, perception, and hidden meaning. His use of ambiguous imagery aligns perfectly with pareidolia, where viewers impose their interpretations onto seemingly random forms.

Max Ernst (1891–1976) pioneered a technique called frottage, where he would rub pencil over textured surfaces and use the resulting patterns as inspiration for his paintings. This method allowed pareidolic images to emerge naturally, which he then transformed into detailed, dreamlike scenes. Ernst’s technique demonstrated how artists could harness pareidolia to create art that blurred the lines between accident and intention. His experimental approach greatly influenced later abstract and conceptual artists.

Contemporary artists continue to explore pareidolia, often integrating it with digital tools. Photographers, such as Axel Brechensbauer, capture everyday objects that resemble faces, turning them into viral social media content. Digital artists use AI to enhance pareidolic effects, creating complex compositions that seem to shift depending on the viewer’s perspective. Whether through traditional painting, photography, or artificial intelligence, pareidolia remains an enduring source of artistic inspiration.

Pareidolia in Everyday Life: Found Art and Accidental Imagery

Pareidolia is not confined to traditional art forms—it appears everywhere in everyday life, often in the most unexpected places. Many people experience pareidolia when they see faces in buildings, cars, or even household items. A common example is the “face” seen in the front grille and headlights of automobiles, where people unconsciously assign emotions to cars based on their perceived expressions. This tendency to anthropomorphize objects stems from the brain’s instinct to recognize and react to faces, even when no real human features are present.

The concept of found art, or “objet trouvé,” is closely linked to pareidolia. Artists who specialize in found art take naturally occurring shapes or accidental patterns and reinterpret them into intentional works of art. A notable example is the work of Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), who often incorporated rough textures and spontaneous forms into his abstract compositions. Similarly, contemporary artists have embraced pareidolic imagery in photography, documenting the countless “hidden faces” that appear in nature and urban environments.

Viral pareidolia images have become a major part of internet culture, with social media platforms amplifying accidental discoveries. Some of the most famous examples include images of Jesus appearing on a piece of toast, a dog’s face in a cup of coffee, or the “Face on Mars,” an optical illusion captured by NASA’s Viking 1 in 1976. These images often spark debate, with some seeing them as divine signs and others dismissing them as mere coincidence. Regardless of interpretation, these occurrences highlight how deeply pareidolia is embedded in human perception.

The rise of smartphone photography has made it easier than ever for people to capture and share pareidolic moments. Entire online communities, such as the r/Pareidolia subreddit, are dedicated to collecting and discussing these phenomena. Whether in clouds, peeling paint, or cracked sidewalks, pareidolia continues to surprise and delight those who take the time to notice it. These accidental masterpieces reinforce the idea that art is everywhere—waiting to be seen by those with the right perspective.

Pareidolia and AI: The Digital Evolution of Pattern Recognition

Advancements in artificial intelligence have taken pareidolia to new heights, pushing the boundaries of how machines recognize and generate patterns. AI programs trained in facial recognition sometimes display pareidolic tendencies, identifying faces in random visual data. This occurs because machine learning models, like human brains, are designed to detect and categorize patterns. The result is an artificial form of pareidolia, where AI “sees” faces or figures that don’t actually exist.

One of the most famous AI projects related to pareidolia is Google’s DeepDream, first introduced in 2015. DeepDream enhances and exaggerates patterns in images, creating hallucinatory, dream-like visuals filled with faces and creatures. By processing images through multiple neural layers, the software amplifies details, often producing bizarre compositions reminiscent of surrealist paintings. These AI-generated artworks have sparked discussions about whether machines can experience creativity or simply replicate human cognitive biases.

Beyond DeepDream, AI-powered image recognition software used in security cameras, medical imaging, and self-driving cars sometimes struggles with pareidolic errors. For instance, early versions of facial recognition software mistakenly identified inanimate objects as human faces, leading to false positives. These cases illustrate how even the most sophisticated technology is not immune to the perceptual shortcuts that define human vision. The implications of AI pareidolia raise ethical concerns, particularly in fields like surveillance and automated decision-making.

Artists have also begun using AI-generated pareidolia as a creative tool. Programs that analyze random textures and produce unexpected imagery allow for new forms of artistic expression. Digital artists blend these AI-generated patterns with traditional media, resulting in compositions that blur the line between human intention and machine perception. As artificial intelligence continues to evolve, it is likely that pareidolia will remain a central theme in discussions about creativity, perception, and the nature of art itself.

The Future of Pareidolia in Art and Culture

As technology and neuroscience advance, the role of pareidolia in art and culture is likely to expand. With the rise of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), pareidolia could become an interactive experience, where digital overlays enhance or manipulate perception. Artists experimenting with these mediums may create immersive environments that play with viewers’ natural tendency to find meaning in chaos. This could lead to a new era of optical illusions and interactive installations based entirely on the phenomenon of pareidolia.

Beyond technology, pareidolia raises fascinating philosophical and psychological questions. Does the brain’s tendency to find patterns suggest a deeper connection between human consciousness and the world around us? Or is it simply a neurological quirk that helps us make sense of random stimuli? Some theories suggest that pareidolia may be linked to pattern recognition in religious experiences, as many reported visions of divine figures are the result of visual illusions. These interpretations continue to fuel debates about the relationship between perception, belief, and art.

The future of pareidolia in artistic expression is bound to evolve as new tools and perspectives emerge. Some artists may push the boundaries of abstract and conceptual art, challenging audiences to reconsider their interpretations of form and structure. Others may integrate pareidolia into neuroscience-based art projects, exploring how perception shapes human experience. As AI becomes increasingly sophisticated, it is possible that machines will develop their own version of artistic pareidolia, further blurring the lines between human creativity and artificial intelligence.

Ultimately, pareidolia will remain a central aspect of human perception, influencing how we interact with both the natural world and artistic creations. Whether through traditional painting, digital art, or machine learning, the tendency to see faces and patterns in randomness will continue to inspire and fascinate. As long as the human mind seeks meaning in the abstract, pareidolia will remain a powerful force in the world of art and beyond.

Key Takeaways

- Pareidolia is the brain’s tendency to perceive familiar patterns, such as faces, in random stimuli.

- Artists throughout history, from Leonardo da Vinci to Salvador Dalí, have used pareidolia as a creative tool.

- AI and machine learning have introduced new digital forms of pareidolia, raising questions about perception and creativity.

- Everyday pareidolia appears in architecture, nature, and viral internet images, influencing modern pop culture.

- The future of pareidolia in art may involve VR, AR, and AI, leading to new interactive and immersive experiences.

FAQs

1. What is the difference between pareidolia and apophenia?

Pareidolia refers specifically to seeing patterns in visual stimuli, such as faces in clouds, while apophenia is a broader term that includes finding patterns in data, numbers, or sounds.

2. How did Leonardo da Vinci use pareidolia in his art?

Leonardo da Vinci encouraged artists to look at random textures and stains to find inspiration for paintings, a practice that aligns with modern pareidolia.

3. What role does AI play in pareidolia?

AI programs, such as Google’s DeepDream, mimic pareidolic perception by enhancing patterns in images, creating surreal and unexpected compositions.

4. Why do people see religious figures in everyday objects?

Religious pareidolia is influenced by personal beliefs and cultural associations, leading people to interpret random patterns as divine manifestations.

5. Can pareidolia be intentionally used in art?

Yes, many artists deliberately incorporate pareidolia into their works, challenging viewers to find hidden images and engage with multiple interpretations.