There is no single Vatican Museum. This is the first and most important truth—one that eludes many of the five million visitors who funnel each year through its marble gates and security checkpoints. What lies beyond is not one museum, but a vast and layered complex: 24 individual institutions, assembled across centuries, entangled within papal palaces, frescoed corridors, loggias, staircases, and chapels. It is both archive and shrine, royal collection and pilgrimage site, imperial spectacle and meditative labyrinth.

The visitor who crosses its threshold is not entering a gallery, but a sovereign entity. The Vatican Museums are an arm of the Holy See. They operate within Vatican City, a microstate that is, technically, a foreign country from the rest of Rome. This political status grants them a unique autonomy—administratively, financially, even ideologically. You are not just walking into a place that shows art; you are entering a space that has shaped world history, theology, aesthetics, and diplomacy for nearly half a millennium.

Founded in 1506, when Pope Julius II acquired the Laocoön sculpture from a vineyard on the Esquiline Hill and placed it in the Cortile del Belvedere, the Vatican collection quickly became an assertion of papal supremacy over both antiquity and the present. But it did not open to the public in any formal sense until the late 18th century. What began as a papal treasure trove became a museum under pressure—from Enlightenment ideals, revolutionary threats, and the changing nature of papal power.

What persists today is a hybrid institution: part sanctuary, part encyclopedia, part propaganda engine. It contains within it:

- The Gregorian Egyptian and Etruscan Museums, housing Roman-era excavations that tell stories older than Christ.

- The Pinacoteca Vaticana, a modern-format art museum with Giotto, Raphael, Caravaggio, and Da Vinci under a single roof.

- The Pio-Clementine and Chiaramonti collections, which function like a sculptural grammar book for the Western tradition.

The visitor is rarely told where one ends and the next begins. And that is deliberate. The Vatican Museums are not arranged pedagogically. They are arranged theologically. Even the architecture works as argument—drawing you, often without realizing it, from the pagan to the Christian, the fragmented to the unified, the bodily to the divine.

The power of anticipation in shaping experience

Most visitors arrive already overwhelmed. The reputation of the Vatican Museums precedes them—not through quiet rumor but blaring global consensus. Everyone knows about the Sistine Chapel, even if they couldn’t name a single panel. Travel forums and cruise ship schedules warn of impossible crowds, and so many people try to “beat the lines” that they form new ones by dawn.

But anticipation, when properly held, can be a form of readiness. The Vatican Museums reward a particular kind of visitor: one who enters not with an agenda, but with an appetite. Those who see only what they came to see will miss everything else. The Sistine Chapel is, yes, a masterpiece—but so is the spiral of space and thought that leads to it. The museum is constructed as a kind of pilgrimage, with thresholds that accumulate meaning as you pass through them.

Outside, before even entering, there is a low stone wall on the Viale Vaticano, and atop that wall sits a pair of colossal sculpted pinecones—contemporary replicas of an ancient symbol of eternal life. Beyond them, the doors open into a subdued modern foyer, built in the 1990s by architect Giuseppe Momo, whose double helix stair you’ll encounter again on your way out. This entrance was designed not to impress but to absorb, to process masses of visitors while holding its breath. The Vatican’s grandeur begins not with flash, but with compression.

A subtle decision awaits you here: to ascend the escalators quickly like a tourist fleeing a queue, or to pause—perhaps even linger—before you begin. Many skip the orientation spaces: the foyer displays, the introductory signage, the ticket-hall friezes. But here, already, are fragments of the journey ahead. Look for the plaster cast of Michelangelo’s Pietà—a replica, yes, but also an interpretive key. Its whiteness lets you see the form without marble’s seductive glow, a kind of seeing before seeing.

The corridor as prelude: learning to look before you arrive

Once inside, many visitors rush toward what they already recognize—pushing past gallery attendants, herded by rope barriers, glancing at directional signage with mild panic. But the first corridors of the Vatican Museums are not just functional. They are instructive. They teach you how to see.

Take, for instance, the so-called Museo Chiaramonti, a long vaulted gallery that most tour groups drift through like a waiting room. This corridor contains more than 1,000 sculptures, fragments, busts, torsos, and imperial heads. Most of them are not individually famous. That is their value. This is not art as stardom but art as constellation.

What begins to emerge, if you allow your gaze to slow, is a deep patterning of ancient Roman identity—what a face meant, how ideal beauty was constructed, how the gesture of a hand, or the line of a calf, could carry meaning across two millennia. Here, you meet not a single emperor, but empire itself: in the broken noses, in the sanded eyes, in the repetition of form.

Midway through this corridor, just before it joins the Braccio Nuovo, a glass-topped cabinet holds oddities—a mummified hand, a collection of ancient dice, tiny bronze animals. These are remnants of human play and belief. They interrupt the grandeur with intimacy. Look long enough, and even the Vatican begins to feel mortal.

One visitor, a Swiss student named Anja G., recalled how she became transfixed by a single bust—a woman with a veil drawn tight across her forehead. “I couldn’t tell if she was alive or dead,” she wrote in her notebook. “She reminded me of my grandmother.” That moment—the recognition of someone entirely unknown—was, in her words, “the most religious thing I felt in Rome.”

Such moments are scattered everywhere. But they require you to slow down long before the ceiling opens above you in Michelangelo’s frescoed vision. The first steps through the Vatican Museums are not antechambers. They are arguments. They ask: what are you looking for? And more importantly—how will you know when you find it?

Keys to the Kingdom: How to Prepare and When to Go

Crowd control: seasons, schedules, and strategy

To enter the Vatican Museums without a plan is to surrender your experience to the will of others. At peak hours—and there are many—visitors may find themselves caught in a dense human tide, funneled shoulder to shoulder through corridors that deserve silence, time, and space. But this is not inevitable. The Vatican is crowded because it is misjudged: most tourists arrive at the same time, for the same reasons, drawn by the same half-truths about timing and access. With minor adjustments, you can reclaim your visit from the algorithmic swarm.

The worst time to go is mid-morning on a summer weekday. By 10:00 a.m. in July, the museum is already saturated, not just with tour groups but with heat, exhaustion, and delayed expectation. August, too, despite Rome’s seasonal emptiness, brings global traffic. Shoulder months like April, May, September, and October have become increasingly saturated as travelers seek the “off-season” that no longer exists. Winter—particularly early February—remains the last truly quiet window, when the pale light in the courtyards sharpens the stone and the corridors breathe a little more freely.

The best time of day is either just before opening or late in the afternoon—though each comes with trade-offs. Early morning access (via premium tickets) lets you see some rooms before they fill, but the pressure to keep moving remains. The afternoon, especially after 3:00 p.m., can feel rushed, but it’s often the only time when the energy of the museum truly calms. The Sistine Chapel, near closing, becomes almost bearable. Guards are still firm, but the sense of ordeal softens into something like a walk among shadows.

Here’s what most guides won’t tell you:

- Wednesdays are ideal, especially in the morning, because St. Peter’s Square is filled with papal audience crowds. They gather outdoors, leaving the museums emptier.

- Fridays are less predictable—the Vatican has experimented with extended evening hours and events, but these vary by season and sell out quickly.

- Monday is not a “quiet” day in the way some assume. While other museums in Rome are closed, tourists redirect to the Vatican, making it busier than expected.

The official opening hours are 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., with last entry at 4:00 p.m. But insiders know that staff begin letting ticket-holders in earlier—as early as 8:30 a.m. if the crowd has formed. Be among them if you must. But more important than your arrival time is your mental posture: you are not there to conquer the museum. You are there to escape the idea that it can be conquered.

Booking secrets and the myth of the “early access” ticket

The Vatican Museums operate an extensive online ticketing system, and it is worth using it—not because you cannot buy tickets on-site (you can, in theory), but because doing so requires stamina, negotiation, and luck. Far better to secure your entry in advance through the official Vatican Museums website, avoiding third-party surcharges and scams.

There is a persistent myth that private companies or expensive tours offer earlier access than anyone else. This is not quite true. All “early access” groups draw from the same general pool of availability granted by the Vatican to ticket holders and accredited guides. What varies is the guidance, the pacing, and the crowd size—not the clock itself.

That said, small-group tours do offer certain practical and aesthetic benefits:

- They manage logistics, helping you bypass lines and bottlenecks efficiently.

- They enforce pacing, ensuring you don’t burn out before you reach the Sistine.

- They provide context, especially for visitors unfamiliar with Renaissance theology, Greco-Roman sculpture, or Catholic history.

But they are not necessary. A well-prepared solo visitor with a strong itinerary and a willingness to pause can enjoy a richer experience than any fast-track group. The secret is not speed. It is sovereignty over your own attention.

If you prefer to wander without a guide but still want structure, consider downloading the Vatican’s official audio guide, or—better yet—print or annotate a museum map in advance, marking key rooms and side galleries. Knowing what not to visit is just as important as knowing what to seek. Skipping the crowded “picture galleries” and doubling back through quiet sculpture halls can make the museum feel like your own.

What to wear, what to bring, what to leave behind

The Vatican is a holy site as well as a museum, and dress codes are enforced—not strictly in the museum galleries, but absolutely in the Sistine Chapel and St. Peter’s Basilica (if you exit that way). Shoulders and knees must be covered. This applies to all genders. Scarves and shawls are acceptable, but tank tops, short shorts, and exposed midriffs are not. Guards will stop you.

Footwear matters more than you think. The floors of the Vatican Museums are hard, uneven, and extensive. Visitors often underestimate the length of the visit—some walking up to seven miles by the end of the day. Choose shoes not only for comfort, but for durability and grip. Rain or spilled liquids make the marble treacherous in spots.

You are allowed to bring:

- A small bag, ideally worn close to the body.

- Water, in plastic bottles only (no glass or metal flasks).

- A camera, though flash photography is prohibited, and no photography of any kind is allowed in the Sistine Chapel.

What you must not bring:

- Tripods, selfie sticks, or drones—confiscated without appeal.

- Umbrellas, if large—they must be checked.

- Large backpacks or luggage—also must be checked and reclaimed later.

There is a free cloakroom service, but it’s located near the main entrance, which becomes inconvenient if you plan to exit through St. Peter’s. Consider carrying only essentials.

Above all, bring an internal discipline: the patience to wait, the courage to linger, and the humility to not see everything. The Vatican Museums are not a checklist. They are a rite of passage. Prepare not just your feet and your schedule—but your mind.

Architecture as Argument: The Building That Houses It All

From papal palace to modern museum complex

It is easy to forget, while shuffling through the galleries under the gaze of marble emperors and gilded ceilings, that you are walking not through a building designed to be a museum, but through a centuries-old palimpsest of papal power. The Vatican Museums are embedded within the Apostolic Palaces—the traditional residence of the pope—whose architecture was never intended to host millions of annual visitors. What you experience today is the result of accretion: structures layered over one another, corridors retrofitted, chapels repurposed, cloisters expanded and then absorbed into secular use.

The original core of the complex traces back to the Cortile del Belvedere, conceived by Donato Bramante around 1506. Commissioned by Pope Julius II, the project was revolutionary: it connected the existing Vatican Palace with a hilltop villa known as the Belvedere, using a series of terraces, staircases, and arcaded courtyards to create a linear promenade of art and architecture. The result was not just a marvel of Renaissance engineering—it was a symbolic axis, an architectural argument linking ancient statues to modern papal authority. The popes were not merely collectors. They were curators of civilization.

Over time, this rational geometry was obscured. Later popes added wings, blocked views, and filled spaces. The Napoleonic threat spurred the construction of new galleries to protect art from plunder. The rise of the museum as a public institution in the 19th century brought further transformations. When you walk the modern Vatican Museums circuit today, you are tracing a hybrid route—part ceremonial, part didactic, part defensive.

In practical terms, the museum occupies roughly 7 kilometers of corridor and gallery space. But its true sprawl is spatial, not just physical. The logic of the building changes as you move through it. One wing adheres to Enlightenment symmetry, with sculptures arranged in tight order. Another mimics a Baroque promenade, full of theatrical rhythm. Others are curiously domestic, with intimate frescoes tucked behind nondescript doors.

This inconsistency is not a flaw. It is a statement. The Vatican Museums are not neutral spaces. They are designed to guide—not only your body but your beliefs.

The architecture of power, guidance, and concealment

Unlike modern museums, which often celebrate transparency, openness, and the freedom of the visitor to chart their own course, the Vatican Museums operate on a different principle: procession. The vast majority of visitors move along a predetermined path, subtly but insistently enforced by ropes, signage, and crowd flows. The architecture steers you forward, not in a loop, but in a one-way pilgrimage culminating in the Sistine Chapel.

This procession is no accident. It mirrors older Catholic traditions of movement through sacred space: from the narthex to the nave, from the periphery to the altar, from chaos to clarity. Even as the exhibits change—from Roman busts to Renaissance frescos to topographical maps—the logic remains consistent. You are being led.

But what is less visible—what few notice beneath the surface of this movement—is the tension between what is shown and what is hidden. For every room open to the public, others are sealed. The Vatican Museums contain hundreds of chambers never seen by visitors. Some are used for administration or conservation. Others remain as they were centuries ago, largely untouched, their frescoes and furniture preserved in private decay.

The famous Stanze di Raffaello, for instance, were once the papal apartments of Julius II. Today, visitors pass through their painted surfaces without fully grasping that these were once lived-in spaces of rule, prayer, and sleep. The spatial transition—from Raphael’s School of Athens to Michelangelo’s Last Judgment—is more than chronological. It’s theological. It leads you from human reason to divine reckoning.

In this way, the museum’s architecture becomes a kind of soft didacticism. It does not announce its lessons aloud. It embeds them in the floorplan.

- Corridors lengthen and narrow as you approach key thresholds, building a sense of anticipation and unease.

- Stairs tilt subtly upward, pulling your eyes toward the heavens before you arrive at sacred ceilings.

- Natural light gives way to artificial glow, reinforcing the sense of departure from the earthly.

These effects are not merely aesthetic. They serve the same purpose as a church’s nave or a cloister’s garden. They prepare the soul.

Courtyards, corridors, and the logic of spatial flow

One of the most important but underappreciated elements of the Vatican Museums is the way it treats outdoor and transitional spaces. The courtyards—especially the Cortile della Pigna (Courtyard of the Pinecone)—are not pauses in the experience. They are architectural breaths, carefully measured to regulate attention and rhythm.

The Cortile della Pigna is framed on one end by a colossal bronze pinecone dating from the 1st century AD, flanked by peacocks that once adorned Emperor Hadrian’s mausoleum. On the opposite side, modernist galleries encroach with functional blankness. The dialogue between ancient symbolism and contemporary architecture is not subtle, but it is meaningful. You are being asked to reconcile two timelines, two aesthetics, two visions of order.

Further along, you pass through narrow transitional halls like the Sala Rotonda and the Sala a Croce Greca—spaces that mimic Roman temples in form and iconography. These rooms act as pivot points, changing not just the tone but the tempo of the visit. The ceilings lower. The air changes. You begin to realize that architecture, in the Vatican, is not just container—it is content.

There is a famous story from the early 20th century of a German art historian, Ludwig Curtius, who stood for hours in the Braccio Nuovo gallery, taking notes not on the sculptures but on the patterns of foot traffic. He was studying how people moved—where they lingered, where they hesitated, what drew them unconsciously toward a statue. His conclusion was simple: architecture guides behavior more effectively than signs.

That principle remains in force. The Vatican Museums do not need to shout. Their walls, thresholds, and spatial rhythms do the work. The building teaches you how to move, where to look, when to stop. If you pay attention, you may come to see that the most powerful curator in the museum is not a person—but the building itself.

The Pinecone Courtyard and the First Test of Focus

A sculpture older than Christianity, and what it means here

In the Vatican Museums, few objects are as ancient or as symbolically overloaded as the bronze pinecone that gives the Cortile della Pigna its name. It is over four meters tall, green with age, and dates from the 1st or 2nd century AD—likely created for a Roman fountain near the Pantheon. Today it stands on a pedestal above a shallow set of steps, flanked by bronze peacocks and backed by a modern retaining wall. Every day, thousands of visitors drift past it, taking photos, meeting tour guides, or glancing briefly upward before moving on. Most never ask: Why is this here?

The pinecone, for all its understated dignity, is no mere decoration. In ancient Rome, it was a potent symbol—associated with regeneration, immortality, and the god Bacchus. It adorned military standards, was used in funerary contexts, and even topped the staff of the cult of Cybele. Its symmetrical spiral reflects not only organic life but the mathematical principles embedded in classical design. Placing it here, in the heart of the papal complex, is a deliberate choice. It makes the courtyard a hinge between the sacred and the profane, between ancient cosmology and Christian theology.

When Pope Clement VII moved the pinecone to this location in the early 1500s, he was participating in the broader humanist project of Christianizing antiquity. The act said, in effect: all truth—pagan, imperial, or revealed—finds its culmination in the Church. That this pagan artifact was flanked by peacocks (symbols of immortality in both pagan and Christian thought) further deepened the allegorical charge. This was not just a garden ornament. It was a theological claim in bronze.

Today, the pinecone holds yet another layer of meaning. It is one of the few ancient sculptures in the Vatican Museums that was not looted, bought, or excavated—but preserved in place, honored continuously across regimes. It embodies endurance without interruption. And yet, precisely because it is located outdoors, and because no guidebook insists upon it, it becomes invisible to the very people who most need to see it.

Bramante’s optical tricks and the eye’s temptation

The pinecone stands at one end of the courtyard’s architectural stage set, but the surrounding frame—the architecture of the Cortile della Pigna itself—tells another story. Originally part of Donato Bramante’s Cortile del Belvedere, the courtyard was once the uppermost terrace in a grand linear progression of gardens, fountains, and arcades. This was not merely a backdrop. It was a visual argument, laid out in space.

Bramante was not designing a neutral enclosure. He was designing a frame for perception. The long axis of the original courtyard emphasized linearity, symmetry, and centrality—values prized by Renaissance thinkers who saw geometry as a reflection of divine order. The pinecone, placed at the head of this axis, became a kind of visual anchor. Everything in the courtyard pulls toward it. Every column and cornice reinforces its centrality.

But there’s more. Bramante was also playing with optics. The flanking loggias are not purely symmetrical. They taper subtly as they rise, creating the illusion of greater height. The steps leading up to the pinecone exaggerate its monumental scale. Even the niches and statuary niches along the walls are calibrated to guide the eye upward and inward. The courtyard isn’t static. It moves. Or rather, it moves you.

These tricks were not just for aesthetic pleasure. They were part of a larger metaphysical program. To perceive correctly—to see in order, to see hierarchy, to be drawn toward the center—was, for the Renaissance mind, akin to thinking rightly about God. Architecture was not just a setting for theology. It was a theology.

This is one reason the modern sculpture placed in the center of the courtyard—Arnaldo Pomodoro’s Sfera con Sfera (Sphere within a Sphere)—provokes such strong reactions. Installed in 1990, Pomodoro’s bronze sphere appears smooth at first glance, but opens to reveal jagged inner gears and broken crusts, as if a mechanical world were tearing itself apart from within. For some, it is a brilliant counterpoint to the classical order of the space. For others, it is an intrusion—too modern, too violent, too self-aware.

But its presence is not arbitrary. It sits precisely where Bramante’s courtyard would have once continued downward, linking to the lower levels of the original complex. In this way, Pomodoro’s sphere becomes a rupture—a sculptural wound where continuity should be. It reminds you, if you’re paying attention, that the Vatican’s grandeur is built not only on harmony, but on fragmentation, rebuilding, and the scars of history.

How tourists miss the most important part of the courtyard

The Cortile della Pigna is one of the Vatican’s most photographed spaces. And yet, paradoxically, it is also one of the least truly seen. Most visitors experience it as a transit zone—a place to gather, to wait, to orient. They look without looking. They take a photo of the pinecone, perhaps posing in front of it with raised sunglasses, but they do not ask why it exists, why it’s here, or what it frames.

The reasons for this are structural and psychological. The courtyard appears early in the museum path, when most visitors are still adjusting—checking their bags, tuning their audio guides, trailing their tour group. Their attention has not yet fully engaged. The Sistine Chapel is still far away, looming in the future like a goal to be achieved. In this early phase, the mind skips over subtlety.

But there is another, deeper reason the courtyard is overlooked: it does not present itself as a narrative. It does not tell a single story. Instead, it invites slow meditation. It requires comparison, symbolism, synthesis. These are not the strengths of most modern museum-goers, who are trained to seek captions, timelines, and big names. The pinecone has none of those. It simply sits there—inscrutable, coiled, watching.

There is a well-known moment recorded in the notebook of an unnamed Jesuit scholar from the 18th century. He wrote, “If you wish to know the soul of the Vatican, do not rush to the chapel. Sit in the courtyard. Watch the light change on the cone.” His advice is not romantic. It is methodical. The pinecone’s surface, with its ancient grooves and dull gleam, changes under the sun. By noon it is sharp. By evening, it softens into velvet. In this shifting play of light and shadow, one learns the first real lesson of the Vatican Museums: that to see is not to glimpse, but to wait.

The courtyard, then, becomes a test. Not of intellect, but of focus. Will you walk past it, eyes already on the horizon? Or will you pause, and ask what the stone is trying to say?

The Belvedere: Anatomy of a Revolution in Seeing

The Laocoön: terror, beauty, and classical resurrection

No visitor forgets their first encounter with the Laocoön. It waits in the Vatican’s octagonal Cortile del Belvedere, encased by shadow and marble, so charged with violence that even the air around it seems to draw back. A priest twisted in agony, his sons beside him, all entangled in the muscular coils of a sea serpent. Their mouths open in silent screams. Their limbs strain toward a salvation that will not arrive.

This is not serenity. It is not Christian. It is not, in any obvious sense, Vatican. And yet it sits at the very center of the papal collection—arguably its genesis. For on January 14, 1506, Pope Julius II sent his architect Giuliano da Sangallo to examine a newly unearthed sculpture in a Roman vineyard. Sangallo brought along Michelangelo. They stood in awe. Within days, the statue was purchased, installed in the Belvedere courtyard, and proclaimed a masterpiece of ancient Greek art. More than that: a key to the Renaissance.

The Laocoön is a Hellenistic sculpture, likely a Roman copy of a Greek original, attributed by Pliny the Elder to the sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus of Rhodes. Its date is uncertain—some say 2nd century BC, others place it later—but its impact is clear. Here was a vision of the human body pushed beyond decorum, beyond harmony, into expressive extremity. This was not the calm of the Parthenon marbles. This was a man crushed by fate, and still beautiful in the moment of his destruction.

Why did Julius II want this in the Vatican? Because it confirmed what he already believed: that pagan antiquity could be not only admired but claimed—absorbed into the Church’s intellectual and aesthetic project. The Laocoön was not, in this reading, a pagan artifact. It was evidence that truth had always pointed toward Rome. In time, Michelangelo’s own figures—on the Sistine ceiling and elsewhere—would echo its torqued forms.

There’s a strange irony here. In Virgil’s Aeneid, Laocoön is punished by the gods for warning the Trojans not to trust the Greeks and their wooden horse. He tells the truth—and is killed for it. His death allows Troy to fall, and Rome to rise. So by displaying the Laocoön at the Vatican, the popes were celebrating not just aesthetic intensity, but mythological necessity: the suffering that clears the way for empire.

The Apollo Belvedere and the invention of “perfection”

If the Laocoön embodies agony, the Apollo Belvedere embodies balance. Just a few steps away in the same courtyard, this god of light and reason stands in contrapposto, one arm raised in command, the other holding the remnants of a bow. His face is placid, his curls idealized, his nudity abstract. This is not a man. It is an idea: perfection, made marble.

Rediscovered in central Italy in the late 15th century, the statue was acquired by the Vatican shortly thereafter and installed in the Belvedere. It became, during the Enlightenment, the most admired sculpture in the Western canon. Johann Joachim Winckelmann, father of modern art history, praised it as the embodiment of “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur.” Napoleon looted it in 1797 and brought it to the Louvre, where it remained until 1815. Its return to Rome was celebrated as a cultural resurrection.

But what is the Apollo Belvedere, really? Some scholars believe it is a Roman copy of a lost Greek bronze by Leochares. Others note its strange inconsistencies—an oddly flat chest, an ambiguous gesture, a head that seems slightly off-scale. And yet none of these flaws diminish its aura. It has been seen, for centuries, not as a portrait of a god, but as a mirror of human aspiration.

The proximity of the Apollo and the Laocoön is not coincidental. The Vatican placed them together to form a dialectic: suffering and serenity, muscle and line, human frailty and divine form. They do not argue. They complete each other. This duality became central to the Renaissance imagination, shaping everything from Michelangelo’s David to Raphael’s philosophers.

Walk between them slowly. Look once at Apollo, then at Laocoön, then back. You will feel the shift in your own gaze—from admiration to empathy, from contemplation to shock. This is the revolution of the Belvedere: it does not merely show you beauty. It changes how you measure it.

The room that redefined Renaissance ambition

The Cortile del Belvedere, now broken up by later additions, was once the nucleus of the Vatican’s spatial and intellectual reordering of antiquity. Donato Bramante’s architectural vision—a cascading sequence of terraces, stairs, and loggias—connected the papal residence to the collection of ancient statuary in a single linear axis. This was the first museum in the modern sense: a space designed not just to hold objects, but to guide viewers through them in a specific, elevating sequence.

This was more than architectural innovation. It was ideological. The popes, especially Julius II, understood art not as a distraction or ornament, but as a form of moral and political instruction. The Belvedere was designed to showcase the continuity between Christian Rome and classical Rome, asserting that the Church had inherited—not obliterated—the world of Virgil and Plato.

The courtyard’s octagonal shape, added later, reinforced this logic. Eight was a number of renewal in Christian numerology—associated with the Resurrection, baptism, and eternity. By reconfiguring the space into an eight-sided gallery, the Vatican gave its ancient statues a new context: not pagan decadence, but Christian sublimation. The human body, once condemned, was now seen as the temple of divine proportion.

In this sense, the Belvedere functioned as both gallery and argument:

- It demonstrated the compatibility of ancient form and Christian function.

- It trained viewers in a visual literacy based on classical ideals.

- It prepared artists to integrate pagan anatomy with sacred narrative.

Indeed, many Renaissance and Baroque artists studied here—Raphael, Michelangelo, Annibale Carracci—copying statues, absorbing their lessons, and reinventing them in paint and fresco. The Belvedere became not just a source of inspiration, but a standard. A model against which all future representations of the body would be measured.

Yet this perfection has its own shadow. The dominance of the Belvedere canon—the white male body, symmetrical, idealized—cast other forms into marginality. African, Asian, and female figures were largely absent from this pantheon. The Vatican’s universalism, like Rome’s, was selective. Its embrace of antiquity did not erase its hierarchy.

Still, standing in the Belvedere today, amid the echo of centuries and the soft crunch of sandals on travertine, one can feel the force of the place. Not just its beauty, but its clarity. It is a space where ideals were forged, and where the human figure became, for better or worse, the measure of all things.

Hall of Animals, Cabinet of Masks: Curiosity and Control

The collector’s eye and the politics of display

Past the iconic Belvedere sculptures and into the less-trafficked corners of the Vatican Museums lies a suite of rooms rarely visited with intention: the Hall of Animals and the so-called Cabinet of Masks. These are not grand galleries. They are not famous. They appear, at first glance, almost ornamental—decorative side rooms filled with marble fauna, broken torsos, and painted floor fragments. But to skip them is to miss a key thread in the Vatican’s museum identity: not the celebration of art, but the organization of knowledge.

The Hall of Animals (Sala degli Animali) was designed in the late 18th century during the pontificate of Pope Pius VI, under the direction of the papal architect Michelangelo Simonetti and the sculptor Francesco Antonio Franzoni. What they created was not merely a sculpture gallery, but a didactic space—a cabinet of curiosities rendered in stone. Dozens of marble animals, both real and imagined, stand arranged along the walls: lions, camels, stags, unicorns, serpents, and sea monsters. Many are ancient fragments, “restored” with startling liberties—missing parts replaced, poses adjusted, hybrid beasts completed with creative flair. It is as much invention as preservation.

This room reflects the 18th-century urge to catalog the world, to tame nature by classification, and to embody it in art. In this sense, the Hall of Animals is less about fauna than about control. The sculptures are arrayed like specimens—Roman taxonomies retrofitted to Enlightenment ideals. They do not merely show animals; they show the human desire to possess them, symbolically and physically.

The Cabinet of Masks (Gabinetto delle Maschere), just a few rooms away, deepens this theme. Though smaller and more enclosed, it offers a dense, layered experience: the floor is a Roman mosaic excavated from the Villa Adriana at Tivoli, complete with theatrical masks and dancers; the walls are lined with idealized female sculptures; the ceiling is painted with neoclassical frescoes that echo the themes below. Again, we find not a single masterpiece, but a microcosm of the Vatican’s collecting ethos—juxtaposition, allegory, containment.

What links these two rooms is not their content but their impulse. Both reflect a curatorial desire to order the universe through fragments. In the midst of the Vatican’s monumentalism, these are miniature empires—spaces where chaos is pinned to the wall and given Latin labels. Here, the museum becomes what it was for so long: a machine of classification.

Sculpted menageries and papal exoticism

To walk through the Hall of Animals is to step into a vision of empire—not the brutal expansion of territory, but the symbolic domination of nature and the distant. The animals come not only from Rome’s actual world, but from its imaginary one. Crocodiles, panthers, and elephants mix with mythic hybrids. Many are shown in combat, or as hunting trophies. Their fangs and claws are stylized. They are less representations of living creatures than emblems of power.

The papal patronage that produced this room was itself shaped by colonial currents. The Vatican, while not a colonial power in the secular sense, was deeply entangled in the politics of European exploration. Missionaries brought back tales—and sometimes artifacts—from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Natural history became a form of spiritual conquest. To collect, to display, to name—these were acts of dominance cloaked in curiosity.

Among the most striking sculptures is a pair of tigers locked in combat, partially restored from ancient fragments, their sinews taut with exaggerated musculature. Another shows a lion devouring a horse—an ancient motif recycled here as a spectacle of raw force. In both cases, the animal is not an individual. It is an allegory. Power consumes grace. The Vatican’s hunters are metaphorical.

It’s worth recalling that these rooms were created just as modern zoology was emerging as a discipline. Linnaean classification, colonial specimen-gathering, and Enlightenment encyclopedias were reshaping how Europeans imagined the natural world. The Vatican’s version, sculpted and selective, was more mythic—but no less ambitious. It sought to bring the full range of creation under the eye of the Church.

- The unicorn, sculpted from composite fragments, represents purity and Christological symbolism.

- The crocodile, partially reconstructed, alludes to Egypt and the biblical plagues.

- The sea monster, invented whole cloth from Roman detritus, stands in for the unknowable.

These animals were not just curiosities. They were building blocks of a sacred encyclopédie—fragments from which the Church’s universal vision could be reasserted.

Art as empire: what these rooms silently proclaim

Behind the playfulness of these rooms lies a harder truth. The Vatican’s collections have always been instruments of authority. What they show, how they show it, and what they omit—these choices speak volumes. The Hall of Animals and the Cabinet of Masks are not neutral spaces. They are assertions. The Vatican, through them, says: We see the world. We name it. We own it.

There is a particularly revealing contrast between the ancient and the restored in these rooms. Many sculptures are composites: a Roman lion’s head attached to a Renaissance body, or a Greek horse’s torso reassembled with modern marble legs. These repairs are not hidden. In fact, they are often emphasized. The museum labels, when they exist, note them casually. But the aesthetic impact is sharper: this is not about authenticity. It is about coherence.

To display a broken fragment is to invite contemplation. To restore it—however fictionally—is to control the narrative. These rooms are full of such reconstructions. They show not what ancient Rome was, but what the Vatican wished it to have been: ordered, universal, intelligible.

The Cabinet of Masks is even more overt in its message. Its floor mosaic, with its Dionysian dancers and grotesque masks, was once a symbol of theatrical release—Roman pleasure, carnival inversion, the liberation of roles. By transplanting it into a quiet, symmetrical chamber, the Vatican neuters its chaos. The revelry becomes reference. The laughter freezes in stone.

This, too, is a kind of power: to take the wild and make it polite. To take the alien and make it decorative. To take history and make it a tableau.

And yet, these rooms also offer something else—something the Vatican did not intend. They reveal the instability of categories. The animals are both real and not. The sculptures are both ancient and new. The masks are both celebratory and eerie. In this tension lies the museum’s most honest moment. Here, amid the marble menagerie, you begin to sense that order is not inevitable. It is chosen. And every choice conceals its opposite.

The Map Gallery: Walking the Boot

Cartographic fantasy meets political propaganda

Few spaces in the Vatican Museums are as visually overwhelming—and intellectually revealing—as the Gallery of Maps (Galleria delle Carte Geografiche). At over 120 meters long and bathed in the cool light of gold and green pigments, this corridor doesn’t merely depict the Italian peninsula. It reshapes it. Painted between 1580 and 1583 under the direction of Pope Gregory XIII, the gallery presents forty topographical frescoes of Italian regions and ports, arranged along both walls. At first glance, it feels like a celebration of geographic knowledge. But look again: this is not just a map. It is a claim.

The entire gallery is a fiction of control. In an era when Italy did not exist as a unified state—when it was divided among duchies, kingdoms, republics, and foreign powers—the Vatican offered its own version of cohesion: a peninsula gathered under the papal gaze. The cartographer responsible for the frescoes, Ignazio Danti, was a Dominican friar and mathematician. But he was also a court artist, sensitive to the politics of vision. His maps are not oriented northward, as modern maps are. They are rotated, sometimes severely, to prioritize Rome as the central axis. Rivers curve to suit the symmetry of the wall. Mountains are flattened or exaggerated for effect.

In this way, the gallery becomes a form of visual dominion. The pope who commissioned it, Gregory XIII, was not content to reform the calendar (though he did that, too). He wanted to project a new Catholic cosmology—one in which space itself was ordered according to papal logic. The walls become acts of sovereignty, each region depicted not in terms of who ruled it, but in terms of how it fit into the Vatican’s spiritual cartography.

It is not incidental that this gallery was built during the Counter-Reformation, a time when the Catholic Church was defending itself against Protestant challenges. While Protestant regions were tearing down images, the Vatican was building a hall of images so vast, it encompassed the known world—at least the part that mattered to Rome. Cartography, here, becomes theology in disguise.

Where geography becomes theater

Most visitors, upon entering the gallery, look up. The ceiling bursts with gilded stuccoes, biblical episodes, and allegorical figures floating through clouded vaults. Angels carry scrolls. Saints hover in architectural trompe-l’oeil. The richness is suffocating. And yet, curiously, the maps below receive less attention. This is by design. The gallery is not meant to be read like an atlas. It is meant to be experienced like a theatre set.

Each frescoed map is framed in painted marble pilasters and festooned with garlands and decorative borders. Bodies of water are rendered in a deep blue-green wash, streaked with white foam; mountain ranges appear like draped fabric. Towns are rendered as tiny architectural glyphs—castles, towers, basilicas—all meticulously labeled. It is tempting to read these maps as realistic, but they are not. They are composite images, derived from Danti’s own cartographic data and local surveys, but adjusted for pictorial coherence.

In one panel, the Apennine mountains tilt toward the viewer, revealing both their peaks and their valleys in a single frame. In another, the port of Venice curls improbably inward, its lagoon compressed to fit the vertical format. These are not errors. They are pictorial strategies. Danti was not trying to navigate. He was trying to persuade.

What emerges, across the gallery, is a form of geographic choreography. The maps invite the viewer to walk the length of Italy, from Liguria to Calabria, from Piedmont to Puglia. You do not sit and study them. You move. The gallery’s length mimics the peninsula’s spine. Each step becomes a form of pilgrimage—not just through space, but through vision itself.

In this way, the gallery echoes the long corridors of medieval cloisters and Roman processional routes. It uses movement to teach. But instead of saints or emperors, it teaches terrain. The message: this land is seen, named, and sanctified. And we, the viewers, are its witnesses.

- The port of Civitavecchia is exaggerated, a nod to its strategic naval value to the Papal States.

- The Kingdom of Naples, then under Spanish control, is depicted with careful neutrality—present, but distant.

- The island of Corsica, ruled by Genoa, is tucked to the side, semi-detached—a reminder that papal vision extends, but does not always grasp.

Even omissions matter. Protestant regions are excluded. The gallery ends at Italy’s southern tip. The world beyond is not part of this cartographic performance. The Vatican has mapped what it considers spiritually and culturally central—and ignored the rest.

Reading the ceiling before the floor

For all the drama of the maps, it is the ceiling that casts the spell. A parade of frescoes—biblical scenes, historical episodes, cosmological symbols—arches overhead in a gilded corridor of heavenly abundance. Executed by a team of artists under Cesare Nebbia and Girolamo Muziano, the ceiling functions like a second text, layered atop the geographic one. If the walls describe physical territory, the ceiling describes moral territory. It is a theology of elevation.

One scene shows Christ calming the storm at sea—a direct contrast to the turbulent political geography of the walls below. Another depicts Saint Peter walking on water, flanked by angels bearing scrolls and keys. These are not random selections. Each biblical story aligns, approximately, with a region on the wall beneath it, suggesting a spiritual counterpart to the earthly map.

The ceiling also reflects the papal ambition of the time. Gregory XIII, like many Renaissance popes, believed in the unity of truth: that science, art, and faith were not enemies but allies. The gallery enacts that unity through spatial logic. Cartography below. Scripture above. Man’s world flanked by God’s.

There is a moment, about two-thirds through the gallery, where the light from a high clerestory window strikes both the ceiling and the maps at once. The effect is theatrical. The gold leaf glows. The painted sea seems to shimmer. A visitor pauses. The illusion holds. It is, briefly, convincing. Rome owns the world. The maps say so. The heavens agree.

But of course, this illusion fractures the moment one steps out of the gallery and into the real, fractured world. The maps are beautiful lies. Italy was not unified in 1583, nor would it be for nearly three centuries. The pope did not rule these lands, except on parchment and paint. And yet, the gallery has endured—not as an archive of geography, but as a record of desire. A map, after all, does not just show you where things are. It shows you what someone once wanted them to be.

The Raphael Rooms: Painting as Total Intelligence

The School of Athens and the philosophy of placement

There is no painting in the Vatican Museums more often photographed—and more profoundly misunderstood—than Raphael’s School of Athens. It dominates one wall of the Stanza della Segnatura, one of four rooms that Raphael and his workshop painted between 1508 and 1524 for Pope Julius II. These “Raphael Rooms” (or Stanze di Raffaello) formed part of the papal apartments, and remain among the most densely loaded environments of Western art. They are not mere decoration. They are epistemologies in fresco.

The School of Athens is, famously, a gathering of the great philosophers of antiquity—Plato and Aristotle at the center, surrounded by an assembly of thinkers from Pythagoras to Diogenes, Euclid to Zoroaster. They inhabit a fictional architectural space, modeled on Bramante’s plans for the new St. Peter’s Basilica. The scene glows with balance, clarity, and intellectual gravity.

But the painting is not simply a celebration of ancient thought. It is a theological and political act. It was placed directly opposite another fresco, The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament, which represents Christian theologians and saints in ecstatic debate beneath a vision of the Trinity. Between these two walls, the room stages a visual dialectic: faith and reason, revelation and philosophy, Christ and Plato.

And then Raphael does something brilliant. He blends the worlds. The School of Athens is not painted in an “ancient” style. Its architecture is High Renaissance; its figures wear classicized drapery, but their gestures and physiques are contemporary. Raphael even embeds likenesses of his peers. Plato’s face is modeled on Leonardo da Vinci. Euclid resembles Bramante. The brooding figure thought to be Heraclitus—slouched on the steps—is Michelangelo, inserted later with obvious admiration and veiled critique. Raphael includes himself, too, at the far right, looking out at the viewer with quiet poise. He is not among the philosophers. He is outside their world, and yet the one who brings it into being.

The room’s placement matters. The Stanza della Segnatura was the pope’s private library and tribunal, where he signed official documents. These walls were never meant as public spectacle. They were part of a working environment, an intellectual theater for a man who believed in the unity of knowledge under the Church. Julius II wanted a space that reflected his rule—not just as a prince, but as a mind.

To stand in this room is to experience the Renaissance at its most confident. It is not merely beautiful. It is ordered, decisive, integrated. It believes that the questions of antiquity can be answered in Christ—and that the answers can be painted.

Julius II and the painter-pope alliance

Pope Julius II (r. 1503–1513) was not a patron in the passive sense. He was a force of nature—imperious, shrewd, volatile—and he understood art as a form of governance. His decision to employ Raphael, then in his mid-20s, was strategic. Raphael had already made a name in Florence, but was not yet tangled in local rivalries. He was ambitious, adaptable, and respectful of authority. Julius saw in him the perfect instrument: a painter capable of translating papal ideology into visual coherence.

Raphael’s contract for the Vatican rooms began with a single chamber—the Stanza della Segnatura—but Julius was so impressed that he ordered the other rooms, already underway by other artists, to be entrusted to Raphael’s workshop. This was no minor insult. It meant erasing the work of Pietro Perugino, Raphael’s own teacher, among others. But Raphael accepted the challenge, and the result was a body of work that rivaled Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel in complexity and reach.

The four rooms—Segnatura, Heliodorus, Fire in the Borgo, and Constantine—follow a trajectory. They begin in synthesis and ascend to drama. The second room, Stanza di Eliodoro, painted as Julius II aged and became increasingly preoccupied with threats to the Church, shifts in tone. Its frescoes—The Expulsion of Heliodorus, The Mass at Bolsena—are darker, more dynamic. They depict divine interventions against enemies, miracles performed to assert ecclesiastical supremacy. The pope appears in several scenes, born on a litter, presiding with somber gravitas.

These rooms are not illustrations of doctrine. They are demonstrations of rule. Julius II, who wore a beard to mourn the loss of Bologna and dreamed of restoring papal authority across Italy, used art as a parallel campaign. Where armies failed, images could conquer. Raphael’s frescoes were battlefields of the mind.

In this alliance between pope and painter, Raphael’s style sharpened. He borrowed Michelangelo’s muscularity, Leonardo’s psychology, and Bramante’s perspective. But he also added something else: composure. Raphael could gather complexity and make it clear. He could paint multiplicity without confusion. That talent, more than any anatomical skill, made him indispensable to Julius II.

Rivalry with Michelangelo: hidden insults and coded praise

The Vatican in the early 1500s was not just a palace. It was a crucible of artistic rivalry. Michelangelo, painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling just steps away from Raphael’s rooms, resented the younger painter’s rise. He accused Raphael of stealing his ideas, of softening truth into elegance. Raphael, for his part, never responded in writing—but his frescoes speak in their own dialect.

In The School of Athens, as mentioned, Michelangelo appears as Heraclitus: hunched, brooding, alone. His boots are worn. His elbow rests on a block of stone. This is not a flattering portrait. But it is not a caricature either. Raphael acknowledges Michelangelo’s genius—even absorbs it—but places it within his own orderly cosmos. The figure is set apart, a symbol of interior struggle. Raphael seems to say: yes, he is great. But he is not central.

Michelangelo, meanwhile, had little patience for Raphael’s grace. He saw it as decorative, evasive. “He was born of art, not of nature,” Michelangelo reportedly said. The insult cuts deep: it implies artifice without substance. Yet even he could not deny Raphael’s power. After Raphael’s death in 1520, Michelangelo would refer to him, grudgingly, as “a great draftsman.”

Their rivalry was more than personal. It reflected a broader tension in Renaissance aesthetics—between intellectual clarity and emotional force, between harmony and passion, between the ideal and the real. In the Vatican Museums, this tension becomes visible in stone and plaster.

Raphael’s rooms offer a vision of synthesis. Michelangelo’s ceiling—ferocious, crowded, cosmic—tears synthesis apart. They are not opposites. They are counterweights. And the Vatican, in a rare act of curatorial genius, places them within walking distance.

To move from the Stanza della Segnatura to the Sistine Chapel is to cross the fault line of Renaissance ambition. On one side: the world as it should be. On the other: the world as it is. Together, they form the Church’s greatest claim—that it alone can hold both.

The Sistine Chapel: Between Heaven and Ceiling

Entering backward: the deliberate misdirection of space

It is perhaps the most visited room in the world, yet few people arrive at the Sistine Chapel with any real sense of its architecture. Part of this is the path itself: after miles of corridors, tapestries, frescoes, stairs, and sculpture, the Chapel comes at the end of a one-way funnel, a terminal chamber into which the entire Vatican Museum pilgrimage empties. You enter through a side door—never the grand west portal, never the axis for which the room was designed. The effect is destabilizing. You are not looking forward, but backward. The altar wall, which should be approached head-on, appears behind you. The ceiling looms suddenly overhead. Orientation becomes mythic.

This confusion is intentional. The Vatican’s modern visitor route is a blend of security logistics and psychological stagecraft. It echoes religious processions, which traditionally approach mystery not by direct confrontation but by circumambulation. You do not storm the divine. You arrive by degrees, already stripped of distraction, already a little undone.

And so, people enter dazed. They are warned to be silent (many are not). Guards bark reminders: no photos, no shouting, no sitting. The crowd surges, then settles. Eyes lift. Breath tightens. Even those who claim indifference feel it—the gravitational pull of the ceiling, 500 square meters of fresco, coiled above like a thunderhead.

What they see is not one painting, but a universe of them. Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam floats at the center of popular memory, reproduced on every postcard and souvenir mug. But it is only a fragment, and it is not at the center of the ceiling. The true axis is theological, not visual: the line from the altar wall’s Last Judgment—a later fresco—to the Separation of Light from Darkness at the ceiling’s beginning. The ceiling unfolds backward in time. You stand in salvation and look toward Genesis.

This inversion matters. It tells you how to read. Not as a tourist, but as a pilgrim. The Sistine Chapel is not an image. It is a cosmology.

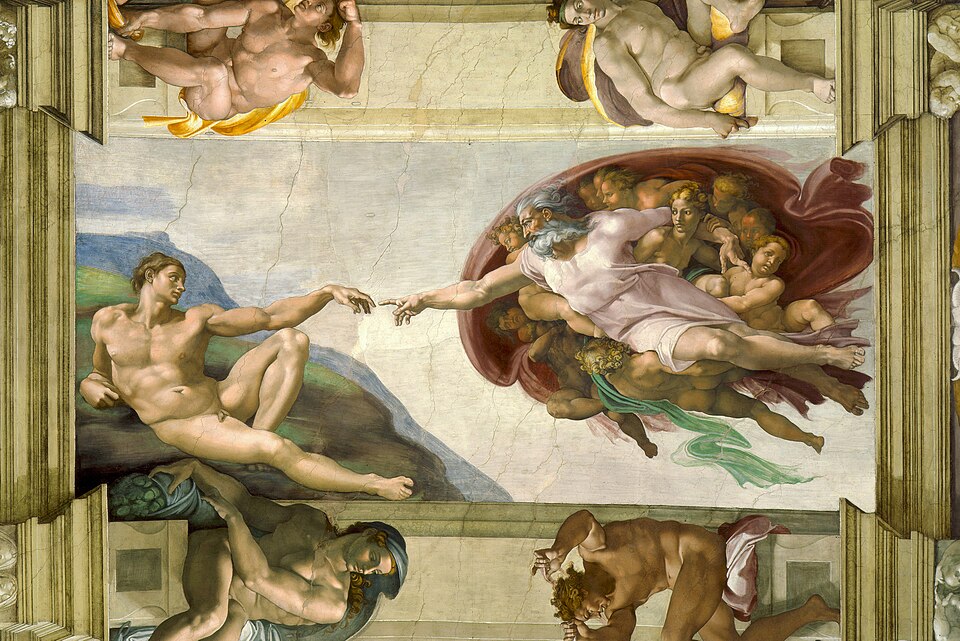

The Creation of Adam and the myth of the spark

No single image has shaped modern conceptions of God and man more than the famous panel where Adam reaches out toward a hovering deity in a swirl of angels. Michelangelo painted it around 1511. It occupies a relatively small space on the ceiling—one of nine central panels—but its clarity and immediacy have granted it immortality.

Two hands extend toward each other. Adam’s is relaxed, still heavy with dust. God’s is taut, electric. The space between their fingers is infinitesimal. That gap—the breath before contact—has become a shorthand for creation itself.

And yet, it is a fiction. Michelangelo does not depict the actual moment of divine touch. He captures the instant before it. That is his genius. Theologically, it is ambiguous: is Adam about to receive life? Or has he already received it? Is he conscious? Or simply awake?

Interpretations multiply. Some scholars note that the red cloak around God resembles the human brain—an anatomical metaphor for divine intellect. Others read the image in Augustinian terms, as a vision of grace preceding action. Still others see it as Michelangelo’s answer to Raphael: less orderly, more charged, more vertical.

What is often missed is the relationship between bodies. God is not abstract. He is muscular, dynamic, storming across the sky. His angels are not cherubs, but full-grown figures, half-cloaked, clustered around Him like thoughts or forces. Adam, by contrast, is earthy, reclining, passive. He does not reach with urgency. He is drawn upward by design.

In this contrast lies the painting’s real drama. It is not about a spark. It is about distance. The unbridgeable gap between divine and human—and the aching beauty of almost.

- The outstretched fingers, despite their fame, never touch.

- The sky behind God, tinged with gold, bleeds into Adam’s dusky background.

- The angels’ faces, some startled, some serene, imply an audience for this birth.

To stand beneath this panel is to feel the tension of potential. Nothing has happened. Everything is about to.

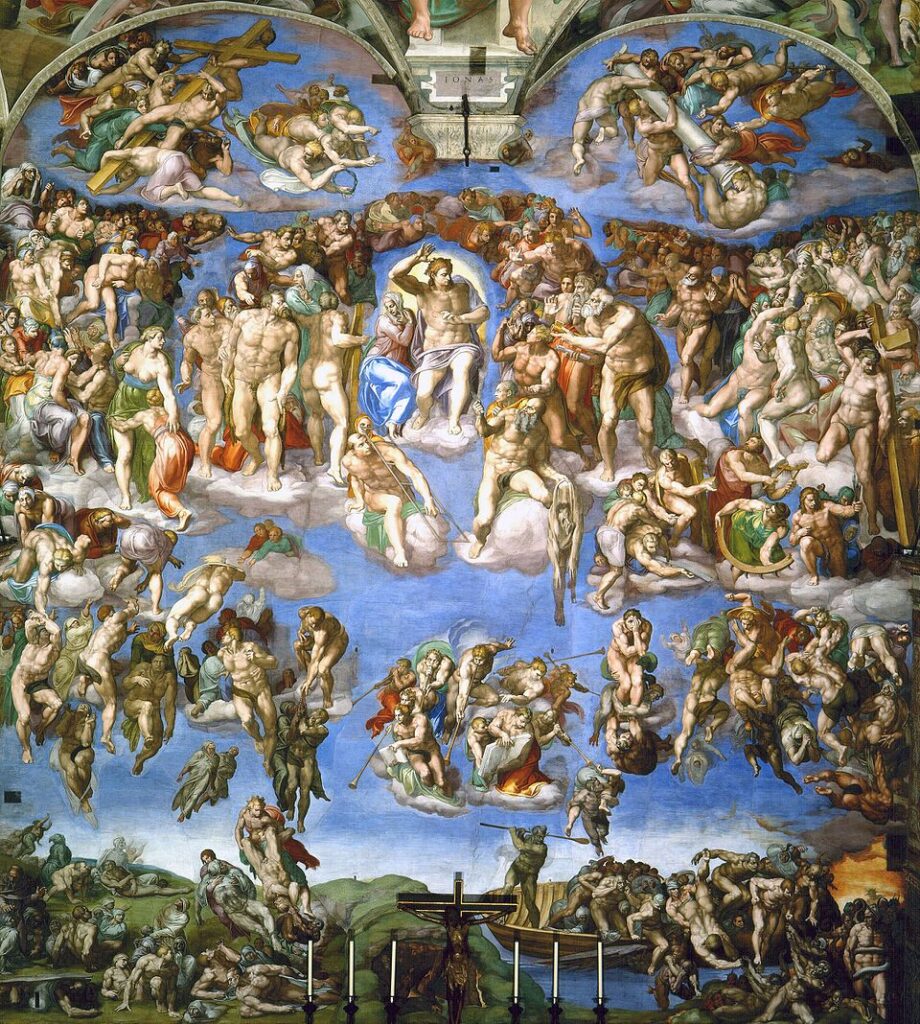

The Last Judgment and the descent of divine rage

Nearly three decades after completing the ceiling, Michelangelo returned to the Sistine Chapel to paint the altar wall. The year was 1536. He was sixty-one. The world had changed. The Protestant Reformation had split Christendom. Rome had been sacked. The mood was darker, the certainties of the High Renaissance shattered.

The Last Judgment, completed in 1541, reflects that upheaval. Gone is the balanced geometry of the ceiling. In its place is a churning vortex of souls: the saved ascending, the damned plummeting, Christ at the center not as a serene judge, but as a divine executioner, arm raised in furious decree. His mother turns away, not pleading, but shielding herself from the force of His judgment.

The figures are massive, exaggerated, stripped of idealism. Their bodies twist in unnatural spirals. Skin peels, eyes bulge, limbs reach and recoil. In one corner, Saint Bartholomew holds his own flayed skin—its face modeled on Michelangelo himself. A bitter self-portrait, hung from the edge of salvation.

The Last Judgment scandalized many. It was too violent, too naked, too honest. Later popes ordered loincloths painted over the genitals. Theologians debated its theology. Was Michelangelo affirming the Church’s vision of judgment, or critiquing it? Was this divine order—or cosmic terror?

Perhaps both. The wall offers no sanctuary. The blessed are not serene. The damned do not wail melodramatically. Everyone is in motion. There is no ground, no stable frame. Even the architecture dissolves into air. The effect is suffocating. You are not looking at a scene. You are inside a storm.

And yet, there is grace—buried, but present. Christ’s raised hand, though fierce, is not closed. His face is unreadable. There is still time. The saved look upward, not smug, but astonished. They have not earned this. They have been lifted.

To stand before this wall after having walked the length of the Vatican Museums is to reach the edge of narrative. This is the culmination. And unlike Raphael’s world of clarity, Michelangelo offers no stable resolution. Only awe.

Modern Religious Art: After the Renaissance Ends

A misunderstood wing: when tourists turn back too soon

Just beyond the Sistine Chapel lies one of the most overlooked and least understood parts of the Vatican Museums: the Collection of Modern and Contemporary Religious Art. Most visitors, if they reach this wing at all, do so by accident. The energy of the crowd peaks inside the Chapel; after that, the flow fractures—some spill out toward St. Peter’s Basilica, others loop back. Very few continue on, let alone with intention, into this curious sequence of galleries.

The irony is sharp. Having just stood under Michelangelo’s terrifying vision of final judgment, many visitors now stand at their own fork in the road and—by force of fatigue or unfamiliarity—turn away. Yet what lies ahead is not an afterthought, but a confrontation. The modern art wing of the Vatican is not just a coda to the old masters. It is the Church’s attempt to reckon, visually, with the 20th century: its wars, its crises, its vanishing transcendence.

Founded in 1973 under Pope Paul VI, the collection was a radical gesture at the time. It sought to restore the severed relationship between the Church and modern art—estranged since the Enlightenment, and especially after the rise of abstraction and secularism in the early 20th century. Paul VI, whose papacy spanned the 1960s, believed deeply in dialogue between faith and culture. “We need artists,” he said in a 1964 address, “we need them to make the invisible visible.”

The result is a complex and often unsettling series of rooms, spread across more than fifty galleries, featuring works by artists from Rodin to Bacon, Chagall to Dalí, Dix to Fontana. There are crucifixions and martyrdoms, angels and abstractions, sacred themes rendered in materials that earlier popes might have denounced as blasphemous or incomprehensible.

To walk these halls after the Sistine Chapel is not anticlimactic. It is theological whiplash. One minute, you are under God’s thunderous gaze. The next, you are surrounded by silence, by fragmentation, by pain. And yet this is precisely what makes the journey necessary. Renaissance art aimed to show the glory of God. Modern art asks: where is He now?

Francis Bacon, Otto Dix, and the horror of faith

In a stark white gallery just beyond the entrance to the modern section hangs a painting by Francis Bacon—Study for a Pope II. Here, the figure of Pope Innocent X, lifted from Velázquez, is reimagined as a screaming, spectral figure in a cage of brushstrokes and shadow. The mouth is open in terror. The robes dissolve into vapor. It is not a portrait of any pope. It is a howl—of power, of guilt, of cosmic dread.

Why is this in the Vatican?

Because, as unsettling as it is, Bacon’s image captures something the Church cannot afford to ignore: the trauma of representation after catastrophe. His screaming popes are not attacks on religion. They are responses to the collapse of authority, the spectacle of dogma, the silence of God in the age of mechanized death. To hang such a work in the Vatican is to admit that the sublime now passes through the grotesque.

Another example: Otto Dix, the German painter and veteran of the First World War, whose Crucifixion hangs nearby. It is not heroic. Christ’s body is mutilated, not idealized. The figures around him are gaunt, skeletal, deformed. This is not Golgotha as envisioned by Raphael or Giotto. It is the Western Front in religious drag. And yet, again, the theology runs deep. Dix’s Christ is not merely a victim. He is the suffering servant rendered in the idiom of a generation that knew gas masks, shell shock, and industrial-scale annihilation.

These are not outliers. The collection includes:

- Marc Chagall’s dreamy, folkloric reimaginings of biblical episodes, suffused with nostalgia and longing.

- Graham Sutherland’s stark depictions of the Passion, with forms flayed almost to abstraction.

- Lucio Fontana’s slashed canvases, which gesture toward resurrection through rupture.

This is not a didactic collection. There are no tidy narratives. But that is the point. Modern religious art does not assert. It asks. It does not explain the mystery. It makes space for it.

What it means to believe after two World Wars

To include modern art in the Vatican Museums was not a curatorial decision. It was a spiritual gamble. The Church, for centuries the commissioner of beauty and symbol, had lost its monopoly on the imagination. The rise of secular modernity, the disillusionment of war, the fragmentation of truth—these were not merely cultural shifts. They were theological shocks.

In this context, the modern wing functions like a confessional. Not for sin, but for doubt. These are not images of triumphant resurrection. They are images of absence, of questioning, of faith under strain. And yet, in their very dissonance, they affirm something crucial: that belief, if it is to live, must pass through history’s furnace.

Consider Giulio Turcato’s stark, minimalist Via Crucis. It reduces the Stations of the Cross to nearly abstract forms—blocks of color, slashes of line. It is barely representational. But it vibrates with feeling. One station bleeds crimson. Another fades to white. There is no face, no crown of thorns, no tomb. And yet, the sequence carries you. Not through doctrine, but through sensation.

Or Giacomo Manzù’s Door of Death—a bronze portal originally intended for St. Peter’s Basilica, with scenes of execution, suffering, martyrdom. It confronts mortality directly, without idealism. In the Vatican context, it is devastating. And truthful.

These works are not for everyone. Many visitors walk past them without pausing, uneasy with the lack of gold and glory. But for those who linger, something happens. You begin to feel the continuity—not of style, but of struggle. Michelangelo’s Last Judgment was terrifying in its time, too. The Church has always wrestled with form.

The question that these rooms ask is not “What does God look like?” but “Can He still be represented?” And their answer, tentative but profound, is: only through fracture.

This is the most honest thing in the Vatican. Not the grandeur, not the order, not the power. But the admission that beauty, in the 20th century, comes covered in ash.

Hidden Rooms, Overlooked Treasures

The Niccoline Chapel: Fra Angelico in secret

Tucked deep within the Apostolic Palace, behind layers of restricted access and centuries of papal privacy, lies a jewel few visitors will ever see: the Niccoline Chapel. Most museum-goers have no idea it exists. Those who do cannot visit it without special permission—granted only to scholars, clergy, or diplomatic guests. And yet, this small room, frescoed in the mid-15th century by Fra Angelico, is among the most spiritually charged and luminously painted spaces in the Vatican.

Commissioned by Pope Nicholas V (from whom it takes its name), the chapel predates the Sistine and Raphael Rooms by several decades. It was meant as a private oratory, a place of prayer and retreat. Its iconographic program centers on the lives of Saint Stephen and Saint Lawrence—two deacons of the early Church, both martyred for defending the poor and proclaiming the Gospel. The narratives are humble, but Fra Angelico’s execution is celestial.

The colors are saturated but soft: ultramarine robes, golden halos, rose-colored walls that seem to glow from within. Angelico was not interested in spectacle. His figures are small, restrained, tenderly human. In one fresco, Saint Stephen distributes alms to the poor; in another, he is stoned to death, his arms raised not in defiance, but in intercession. Every detail is devotional. Every composition breathes.

The architecture in the frescoes mirrors the architecture of the room itself—arches within arches, niches within niches—creating a vertiginous effect, as if the space folds in on itself in prayer. And in the ceiling vault, above it all, the Four Evangelists are seated on thrones amid stars. They are not roaring with authority. They are listening.

The Niccoline Chapel is not part of the visitor route. It is behind locked doors. But its existence casts a long shadow over the rest of the museum. It reminds us that much of the Vatican’s power is hidden—not in grand public spaces, but in quiet corners. That the holiest room may be the one you’ll never enter.

And that Fra Angelico, canonized in 1982, was not simply a painter of faith. He was a painter of interiority—proof that silence, when painted well, can be louder than thunder.

The Etruscan Museum and the memory of Rome before Rome

Far from the crowds pressing into the Sistine and Raphael Rooms, the Vatican Museums contain an entire wing that most visitors miss entirely: the Gregorian Etruscan Museum. Founded in 1837 by Pope Gregory XVI, it was one of the first major efforts to institutionalize the study of the Etruscans—an ancient civilization that flourished in Italy centuries before the rise of the Roman Republic.

To enter these galleries is to step sideways in time. The marble disappears. The narratives change. You are no longer in the world of popes and painters, but in a far older, quieter cosmos—one of funerary urns, bronze mirrors, ceramic fragments, and votive figurines. The rooms smell faintly of clay and iron. The light is dimmer. The mood shifts.

The Etruscans remain mysterious even to scholars. Their language is only partially deciphered. Their origins, still debated. But their art tells us much: of sensuality, of ritual, of closeness to the earth. One sarcophagus shows a married couple reclining together in death, their arms around each other—not in fear, but in intimacy. Another display case holds a bronze liver, used for divination, its surface incised with the names of deities—a tactile map of the divine.

This is not the Rome of conquest. It is the Italy that preceded it. And in a building so dedicated to imperial legacy, the Etruscan Museum whispers an older truth: that the soil beneath the Vatican was once sacred in a different tongue.

Three objects not to miss:

- The Sarcophagus of the Spouses: a 6th-century BC terracotta tomb lid, tender and timeless.

- The Mars of Todi: a bronze votive statue of a warrior-priest, delicately balanced and alert.

- The Cista Ficoroni: an intricately engraved bronze box, used to store women’s toiletries, myth and daily life entwined.

Few tourists make it this far. But those who do often describe the experience as “resetting.” Here, away from marble saints and frescoed ceilings, you begin to understand how deep the Vatican’s roots truly go—and how many civilizations it rests upon.

Minor masterpieces in major silence

There are dozens of small rooms and isolated treasures in the Vatican Museums that defy inclusion on any official “highlights” list. They are the places where one turns a corner and finds a forgotten altar, a lone statue, or a window framing the sky. These are the spaces that don’t appear in guidebooks but stay in the mind for years.

One such room is the Sala delle Nozze Aldobrandini, named after the ancient Roman fresco it houses—The Aldobrandini Wedding. Removed from its original site and brought to the Vatican in the 19th century, it depicts a bride preparing for marriage, surrounded by attendants. The style is delicate, the mood almost Hellenistic. There is no drama. Just a sense of time unfolding.

Another is the Room of the Immaculate Conception, frescoed by Francesco Podesti in the 19th century. It tells the story of the dogma’s declaration in 1854, in a visual style that attempts to bridge Raphael and Romanticism. It is earnest, overwrought, often empty—but suddenly, in one panel, you glimpse something: a quiet woman, not Mary, standing off to the side, watching. She seems to know something no one else does.

There is also a small painting, rarely noticed, by Melozzo da Forlì: an angel, fragmentary, suspended in air, gazing down with translucent calm. It once belonged to a larger fresco in the Church of the Holy Apostles, dismantled long ago. Here, alone on a white wall, it glows. A leftover. A survivor.

These minor masterpieces do not clamor for attention. They reward wandering, not pursuit. And in a museum so burdened by expectation, they offer an antidote. They remind the viewer that greatness is not always scale. That the most lasting encounters happen when you are off-guard. That, sometimes, the most sacred thing is a single figure in a forgotten room, still watching, centuries later, in the quiet.

Exit Through the Spiral: Momo’s Double Helix Stair

The genius of a stair you barely notice

The final architectural experience of the Vatican Museums is, fittingly, a descent. After hours spent ascending through art and time—through sculpture halls, Renaissance frescoes, cartographic fantasies, and apocalyptic visions—you find yourself ushered gently, almost unconsciously, into a cool, dim atrium. And there it is: the spiral staircase.

Most visitors walk down without pause. It comes at the end of the day, when feet are sore, when minds are crowded, when the grand arc of the museum has blurred into a sequence of remembered highlights. But the staircase—designed in 1932 by Giuseppe Momo—is one of the Vatican’s most brilliant, if understated, architectural gestures. It is not old. It is not painted. It does not tell a story. And yet, it encapsulates everything the Vatican Museums are: a descent that feels like a rise, a movement through structure that teaches without words.

Momo’s staircase is a double helix: two intertwined spirals—one for ascending, one for descending—that never touch. You walk down one curve, while an invisible twin ascends alongside, separated by a central column and a low balustrade. The illusion is seamless. It feels continuous, effortless. But behind the ease is mathematical complexity and symbolic depth.

The spiral form evokes many things: the DNA of life, the staircases of medieval towers, the winding forms of Baroque churches. But in this context, it resonates most with theological architecture. The spiral does not trap. It leads. It pulls you downward, yes—but toward light. The center is open to the sky above. As you descend, the space opens wider, not narrower. You leave not through compression, but through expansion.

And this is not metaphorical. After hours in narrow corridors and crowded galleries, the spiral offers actual air. It lets you breathe again.

How modernity sneaks into the ancient

Giuseppe Momo was not a radical modernist. He was a court architect—practical, elegant, modest. When tasked with designing a new exit for the Vatican Museums in the early 1930s, he chose a form that would feel timeless, yet function with modern efficiency. His staircase was built for flow. It needed to accommodate thousands of visitors per day, to guide them gently but quickly out of the museum without creating bottlenecks.

But Momo did more than solve a logistical problem. He inserted a modern gesture into the heart of the Vatican—quietly, without disruption, without arrogance. The staircase is not ostentatiously “modern.” There is no concrete, no chrome. It is clad in brass and stone. Its lines are clean but classical. It whispers rather than shouts.

And yet, once you know to look for it, the symbolism becomes hard to ignore. This is a spiral built during a time of rising fascism and architectural spectacle. The 1930s in Italy were years of monumental scale, of muscular public buildings, of harsh nationalist lines. Momo’s work is the opposite: a private elegance, a structure that does not dominate but directs. It is modernity made humane.

For decades, the Vatican Museums had resisted overt modernization. The installation of electricity was delayed. Climate control was minimal. The attitude was: let the art speak. But Momo’s stair marked a shift. It said: flow matters. Experience matters. Architecture is not separate from curation.

And in this sense, the stair becomes the museum’s epilogue. You have seen the gods and the saints. You have passed through judgment and resurrection. Now, as your body coils downward, you begin to reenter the world—not with a crash, but with grace.

Leaving the museum without leaving the spell

Most museum exits are abrupt. They spill you into gift shops, cafés, or traffic. They break the trance. But the Vatican’s spiral descent allows something gentler. You leave the museum with your gaze still inward, your pace still ceremonial. The final steps are almost dreamlike.

At the bottom, there is often a cluster of people: some taking photos, some resting on the steps, some gazing upward. From below, the staircase reveals its full geometry—a spiral cone of light and shadow, as elegant as a seashell. Its lines ripple upward like smoke. For a moment, the building itself becomes sculpture.

There is a story told by one Vatican museum guard—let’s call him Matteo—about a woman who reached the bottom of the stair and burst into tears. Not because of fatigue, or sadness, but because, as she explained, “It was the only part of the museum no one tried to explain to me.” She had spent the day being told what to see, what to feel, what mattered. But here, in the spiral, she had simply moved. And in that movement, something unlocked.

That’s the secret of the spiral. It doesn’t teach. It lets go. It trusts that after everything you’ve seen, you don’t need a guide. You need release.

The Vatican Museums are a cathedral of human ambition. They contain the most sustained visual theology ever assembled: beauty, terror, logic, madness. But in the end, you leave not through doctrine, but through design. A spiral. A gentle descent. A curve through shadow and light.

And as you step out into the Roman sun, blinking, silent, changed, you may not remember every room or every painting. But the feeling will remain: that you walked through a structure built not just to house art, but to transform attention itself.