Long before it bore the name Mariupol, the low hills and river mouths near the Sea of Azov were home to a series of cultures whose artistic output was not painted or sculpted in the traditional sense, but buried in the ground, embedded in the rituals of the dead. Among the most significant archaeological discoveries in the region is the Mariupol Cemetery, unearthed in the 1930s, which lent its name to what is now known as the Mariupol culture—a late Mesolithic to early Neolithic population that thrived around 5000–4000 BC. Though rudimentary by later standards, their material remnants hint at a complex visual and symbolic world, especially in their burial customs.

The Mariupol Cemetery revealed more than 100 skeletons laid out in extended supine positions, many accompanied by ochre, flint tools, bone artifacts, and decorative items. Red ochre, sprinkled over the bodies, served both aesthetic and ritual functions—it stained the earth, the skin, and possibly the afterlife itself. These graves weren’t merely utilitarian or hygienic; they were visual compositions, stages on which the drama of death played out with an evident sensitivity to symmetry, orientation, and adornment.

Among the most intriguing finds were pendants and beads made from animal teeth and shells, arranged deliberately on the bodies. The repetition and placement of these ornaments suggest early systems of symbolic thinking—perhaps totemic, possibly aesthetic. Some theorists have argued that the Mariupol culture was not isolated but part of a broader web of steppe-belt societies, whose artistic expressions reflected both localized identities and interregional influences.

Scythian, Sarmatian, and Greek Influences Along the Steppe

The Mariupol region was never a cultural vacuum. Its location on the northern coast of the Azov Sea—at the edge of the Pontic Steppe and near the ancient Bosporan Kingdom—meant it served as a corridor for a rotating cast of nomadic and colonizing peoples, each contributing layers to its artistic strata. By the early Iron Age, the steppes around the future Mariupol were within the spheres of both the Scythians and the Sarmatians, Iranian-speaking peoples known for their distinctive burial mounds (kurgans), goldwork, and portable luxury items that often functioned as political gifts and ritual tools.

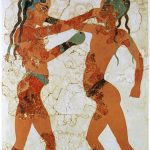

The Scythians, in particular, left behind a visual lexicon carved into metal: stylized stags in leaping poses, composite mythological beasts, warriors in profile, and vessels adorned with scenes of combat or divination. Their art was not merely decorative; it was mobile propaganda, expressing both individual prestige and tribal mythos. While large-scale Scythian finds cluster further west, the edges of their material world—bronze weapons, jewelry, and animal-style appliqués—have been found in the Azov basin as well, including in the area near Mariupol.

By the 6th century BC, Greek colonies such as Olbia and Panticapaeum began to exert cultural and economic influence across the Black Sea’s northern rim. Their pottery, coins, inscriptions, and sculptural fragments began to appear in settlements along trade routes reaching into the steppe. The Bosporan Kingdom, which maintained a hybrid Greco-Scythian court culture, likely had indirect ties to communities around the lower Kalmius River. Amphorae shards and fragments of Hellenistic ceramics uncovered near Mariupol testify to these connections, suggesting the presence of Greek trade goods, if not Greek settlers themselves.

The resulting synthesis—where nomadic abstraction met Hellenic figuration—produced a unique aesthetic hybrid. Metal plaques combine steppe dynamism with Mediterranean symmetry; jewelry mixes pastoral motifs with urban craftsmanship. This visual blending foreshadows the layered cultural identity Mariupol would embody centuries later.

Petroglyphs, Kurgans, and the Archaeology of Symbol

While few large-scale artworks survive from the region’s prehistoric and early historic periods, the landscape itself carries visual traces—etched into stone, piled into earth, arranged across plains. Kurgans, or burial mounds, remain among the most striking and persistent sculptural features of the steppe. Though looted or weathered by time, they were once centers of ritual display, surrounded by stelae, animal sacrifices, and offerings meant to bind the living to the dead through permanent forms.

Many kurgans featured stone stelae known as balbals, anthropomorphic markers sometimes resembling warriors or elders. While most known examples are from later Turkic nomads, earlier versions have been found in the broader Pontic-Caspian region. Some are adorned with shallow carvings—eyes, weapons, belts—indicating not just a memorial function but a narrative one: these were ancestral presences in stone, witnesses rather than monuments.

Further east, in the Don and Kuban regions, petroglyphs carved into rock faces and boulders depict herds, hunters, spiral forms, and abstract grids. Though no major petroglyph site has been found within Mariupol’s modern limits, similar carvings likely existed in riverine zones or have been lost to development. What remains instead are fragments—a bronze mirror here, a carved pin there—requiring a kind of interpretive patience akin to deciphering a broken script.

Yet the absence of monumental architecture or preserved murals should not suggest a lack of artistic complexity. Art in this region was transitory, coded, and deeply integrated with ritual practice. It moved with the herds, burned in funeral fires, was buried under tumuli, or worn into the flesh of the dead. In some ways, its invisibility today is part of its legacy: an art shaped not for permanence, but for memory.

Foundations and Frontiers: Mariupol’s Early Cultural Landscape

Cossack Outposts and Greek Settlements

Mariupol did not emerge in a vacuum. Its official foundation in 1778 as a designated town was a formalization of earlier, more fluid frontier life. By the early 18th century, the area was already a contested space—part marshland, part military zone, part migratory artery—watched over by Cossack patrols and dotted with small Greek villages left behind by traders and refugees from Crimea and the eastern Black Sea. These early communities produced little monumental art, but their visual culture—icons, embroidery, woodworking—was rich with symbolic density and hybrid identity.

The Greek presence was neither incidental nor aestheticized. In 1778, Catherine the Great’s imperial edict forcibly relocated thousands of Orthodox Greeks from the Crimean Khanate into the Azov region to serve as a buffer population on the empire’s volatile southern flank. These resettled Greeks brought not only their language and religion but a portable culture of sacred image-making and artisanal skill. Their churches became local centers of visual production. Wooden structures were soon replaced by masonry ones, and inside these chapels, wall paintings and portable icons followed the Athonite style: dark backgrounds, elongated faces, gold-leaf halos, and geometric robes—hallmarks of late Byzantine influence.

Yet these forms did not remain untouched. In their new setting, they began to absorb features of their Slavic surroundings. Ukrainian and Russian icon traditions, particularly the Pskov and Novgorod schools, crept in—broader facial planes, more dynamic poses, and brighter palettes. It was not unusual to find icons painted locally that featured inscriptions in both Greek and Church Slavonic, suggesting a fusion that was not only artistic but political. The iconostasis of the Church of St. Haralambos, one of the earliest known Greek churches in Mariupol, blended baroque motifs with rigid Byzantine canons, creating a hybrid style specific to the region.

The City Plan of 1778 and Cultural Importation

The founding of Mariupol as an administrative town in 1778 was itself an act of artistic imposition. Like many cities created during the imperial expansion of Russia’s southern frontier, Mariupol was given a geometric, centralized plan based on Enlightenment-era principles of order and symmetry. The grid pattern of streets, anchored by a central square and bordered by military and ecclesiastical buildings, reflected more than bureaucratic efficiency—it was a visual ideology, one that attempted to overwrite the region’s chaotic past with a fixed and rational future.

Art, in this setting, became a state function. Early civic architecture, such as the first government buildings and Orthodox cathedrals, followed the prevailing neoclassical taste imported from St. Petersburg. Columns, cornices, and symmetrical façades spoke the language of Russian Enlightenment authority. The effect was aspirational: a frontier town dressing itself in metropolitan aesthetics.

But this wasn’t simply mimicry. Local builders and iconographers adapted these forms to the materials at hand—stucco rather than marble, timber foundations instead of stone. A fascinating example is the 19th-century renovation of the Church of the Intercession of the Virgin. Its external profile reflected a provincial baroque, while inside, locally trained artists painted frescoes in a post-Byzantine idiom using egg tempera on lime plaster. The church stood not only as a place of worship but as a microcosm of Mariupol’s stylistic negotiations: Greek in liturgy, Russian in design, steppe in materials.

Meanwhile, trade continued to shape the artistic vocabulary. As Mariupol grew into a port town, foreign goods arrived: German glass, Venetian pigments, Persian fabrics. Decorative patterns from abroad began to appear in domestic items—embroidered shirts, carved bedframes, tiled stoves. These objects were rarely signed or attributed, but their proliferation created a kind of vernacular visual economy that sustained itself outside the realm of elite or institutional art.

Religious Iconography in the Borderlands

In Mariupol’s early years, religious art remained the most prominent—and accessible—mode of visual expression. While civic sculpture and landscape painting were largely absent, churches and homes were filled with icons, crosses, and devotional murals. These were not static heirlooms but part of daily life: kissed, carried, covered, burned, restored. As the 19th century progressed, regional schools of icon painting began to emerge, staffed by local Greek and Ukrainian artists trained in Kyiv, Kharkiv, or Rostov-on-Don.

One of the lesser-known but influential figures of this period was Ioannis Papadopoulos, a second-generation Greek painter who established an icon workshop near the Kalmius River in the 1840s. His work shows a confident synthesis of Byzantine formality with folk expressiveness—cherubs with mischievous eyes, saints with subtly regional clothing, backgrounds peppered with flowers that could have come from local embroidery. Several of his icons, now housed in the Donetsk Regional Museum of Art, demonstrate this stylistic hybridity: a Saint Nicholas painted in tempera with Hellenistic proportions, flanked by angels holding scrolls in Cyrillic.

Even more striking were the wall paintings in rural chapels, where artists were freer to experiment. One surviving example from a now-destroyed church in Sartana (a village just outside Mariupol) featured a Last Judgment scene with fiery reds, elongated demonic forms, and an architectural backdrop modeled not on Jerusalem, but on the domes and factories of Mariupol itself. Such images blurred the line between sacred time and local geography, turning theology into civic allegory.

- In these early decades, three patterns emerge that would echo through Mariupol’s artistic life:

- Synthesis: Cultural traditions didn’t erase one another—they layered, blended, and argued visually.

- Portability: Art was designed to move—through trade, through conquest, through exile.

- Adaptation: Materials, styles, and motifs were reshaped by climate, politics, and necessity.

What began as a pragmatic outpost grew into a multiethnic town with a distinctive visual dialect—neither entirely Greek nor Russian, neither provincial nor cosmopolitan. Its art, even in its formative years, was marked by a refusal to fit cleanly into imperial narratives.

Greek Voices, Russian Frames: Identity in 19th-Century Mariupol

The Resettlement of Crimean Greeks and Their Artistic Legacies

By the mid-19th century, Mariupol had grown from a remote military colony into a culturally complex town with a population that included Greeks, Russians, Ukrainians, Jews, Armenians, and Tatars. Yet among these, the Crimean Greeks retained a distinct, often dominant, cultural presence—one deeply rooted in religious tradition, oral history, and visual craft. Their artistic legacies, shaped by displacement and preservation, became both markers of ethnic endurance and instruments of civic negotiation.

Following their mass relocation in 1778–1780 under Catherine II, the Greek population was granted relative autonomy in cultural and ecclesiastical matters. Many settled in satellite villages—Sartana, Yalta, Urzuf—while others migrated to Mariupol proper. These Greek enclaves maintained traditions that predated Russian rule by centuries, including the making of icons, carved wooden church fittings, and intricate embroidery used in liturgical and domestic contexts.

What distinguished the art of these Greeks was not just its Byzantine ancestry, but the subtle way it absorbed the anxieties of exile. Icons produced in village workshops were often conservative in form, yet the themes selected—martyrs, wanderers, heavenly cities—reflected a quiet theology of loss. Crosses were carved from local steppe wood rather than imported cedar. Silver was scarce, so frames were sometimes fashioned from tin and brass, engraved by hand with floral motifs borrowed from Pontic embroidery or Crimean architecture. This was a culture of survival, and its art bore the marks of both continuity and improvisation.

Over time, a distinct “Mariupol Greek” school of iconography emerged, largely undocumented but traceable through stylistic comparison. These icons are usually unsigned, but several recurring features help identify them: compact figures with rounded, childlike features; heavy use of blue and green pigments; and border decorations that blend Orthodox motifs with ornamental designs more typical of peasant textiles. While rarely exhibited in formal galleries, these works populated homes, chapels, and community centers, maintaining a visual continuity between the lost homeland and the new frontier.

Folk Art, Liturgical Forms, and Language Politics

Art in 19th-century Mariupol was not confined to religious settings. Folk art—especially among Greeks and Ukrainians—played an equally important role in expressing local identity. Painted ceramics, embroidered tunics, carved chest lids, and wedding textiles all functioned as visual storytelling tools, often passed down through generations. These forms rarely entered formal art historical accounts, but they dominated the interiors of everyday life.

In particular, the embroidery produced by Mariupol’s Greek villages achieved a level of sophistication and symbolic density that rivals more well-known Ukrainian examples. Patterns were typically geometric, with diamonds, meanders, and tree-of-life motifs stitched in bold colors on linen or wool. These were not merely decorative. Each pattern encoded familial, village, or devotional significance. Certain border designs were associated with mourning, others with fertility or protection. Like icons, they were objects of continuity, memory, and instruction.

Liturgical forms, too, became vehicles for artistic experimentation. Clerical vestments produced locally often featured unique hybrid patterns—Byzantine motifs stitched with techniques borrowed from Ukrainian peasantry. Metalwork chalices and gospel covers, while modest in scale, reveal a remarkable attention to detail and craftsmanship. One example held at the Odessa Museum of Regional Studies—believed to originate from a Mariupol parish—features Greek inscriptions etched beside stylized tulips and sunbursts more typical of Crimean Tatar design, evidence of the complex interchange that defined the region.

This flourishing of local craftsmanship occurred within a linguistic and political tension. The Greek community, though protected in theory, was under increasing pressure to adopt Russian language and educational norms. By the 1860s, Russian Orthodox clergy and imperial school officials began pushing for the replacement of Greek liturgical language with Church Slavonic, and for the Russification of iconographic styles. This cultural pressure seeped into art. Some icons from this period display a strange duality: the names of saints written in Russian, but painted in a clearly Hellenic style. Others show an awkward transition toward the more theatrical, sentimental aesthetics favored by the Russian Academy of Arts—a softening of features, a syrupy pathos in the expressions, a preference for Renaissance-like realism over stylized abstraction.

This stylistic dissonance mirrored a deeper uncertainty: whether Mariupol’s Greek community could maintain its distinct visual identity within an empire increasingly concerned with centralization and assimilation.

A Peripheral Presence in Imperial Cultural Maps

From the perspective of imperial Russia’s major cultural centers—St. Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa—Mariupol was a backwater, useful primarily for grain exports and population control. It rarely appeared in art journals, museum acquisitions, or official exhibitions. There were no art academies, few professional painters, and only a handful of public monuments. This peripheral status might suggest artistic stagnation, but in fact, it created a space where local traditions could persist with minimal interference.

Still, the second half of the 19th century saw the beginning of formal cultural institutions. In 1881, the city hosted its first publicly funded exhibition of ecclesiastical art, featuring works from village parishes and private collectors. The event was modest—held in a church annex—but its catalog provides an invaluable record of the region’s artistic tastes. Among the most praised items were carved icon screens, hand-copied gospels, and an embroidered epitrachelion stitched in 1814 by a group of village widows in memory of war dead.

There were also early attempts at secular art patronage. A local noble family, the Chernovs, briefly sponsored a drawing school for orphans and apprentices, inviting itinerant artists to teach landscape and portrait painting. Some of these students went on to decorate civic buildings or paint shop signs—a humble but crucial step in the development of a local visual idiom.

Yet Mariupol never became a node in the imperial cultural circuit. Its artists rarely studied at the Academy in St. Petersburg; its folk traditions remained uncollected by Moscow ethnographers. This marginality, paradoxically, preserved certain archaic forms that vanished elsewhere. Until the early 20th century, some Mariupol churches still commissioned icons using egg tempera and gold leaf, long after urban parishes had adopted factory-produced prints.

- Three underrecognized aspects of this era remain vital to understanding Mariupol’s visual culture:

- Persistence of Local Iconography: Even under Russification, Greek religious styles retained formal independence.

- Interethnic Influence in Craft: Folk art fused Greek, Ukrainian, and Tatar motifs into distinctive regional forms.

- Cultural Isolation as Protection: Lack of elite patronage allowed vernacular traditions to flourish without external filtering.

In the end, 19th-century Mariupol was neither artistically provincial nor culturally silent. Its art thrived at the interstices—between empires, languages, and identities. These tensions would only deepen in the 20th century, when modern ideologies and industrial expansion began to rewrite the city’s aesthetic language with greater force and precision.

Industrial Smoke and Urban Sketches: Art in the Age of Steel

The Rise of Industry and Its Visual Reverberations

The year 1896 marked a transformation in Mariupol that would reshape its landscape and, in time, its visual culture. That year, the Nikopol-Mariupol Mining and Metallurgical Society began constructing what would become the city’s industrial spine: the Ilyich Iron and Steel Works. Coupled with the development of the Azovstal steel plant in the 1930s, this industrial surge altered Mariupol’s skyline, economy, and demography—and with it, the way the city was represented, both by outsiders and by its own artists.

Early artistic responses to industrialization came not from established painters or sculptors, but from draftsmen, surveyors, and engineers whose sketches, blueprints, and elevation drawings recorded the evolving infrastructure of steel mills, smokestacks, and rail lines. Though functional, these images often conveyed a quiet grandeur—precise lines converging toward newly laid tracks, furnace towers rising like secular cathedrals. In time, these utilitarian images would form the foundation for a distinct urban visuality: a steel aesthetic, one that would echo through murals, posters, and state art for decades.

But the earliest signs of a more poetic engagement came in watercolors and ink drawings made by amateur artists—teachers, clerks, and students—who began to sketch the growing contrast between old Mariupol and its industrial appendages. One anonymous series, preserved in the local archives and dated circa 1908, depicts the Kalmius River curling past fields into a cluster of smokestacks, with annotations like “before shift” and “under fog.” These works are not nostalgic; they neither glorify nor condemn. Rather, they mark the beginning of a visual reckoning with a new civic identity—Mariupol as a steel town, built by the labor of thousands, increasingly faceless and mechanized.

By the 1910s, photography began to enter the public consciousness, and with it came new visual documents of industrial life. Panoramic images of the port, the rolling mills, and housing blocks for factory workers began to appear in local newspapers and regional reports. These early photographs were stiff, staged, and institutional—but they showed the city as a new kind of space: one built not around churches or marketplaces, but around production, hierarchy, and smoke.

Workers, Realism, and Early Visual Documentation

As Mariupol’s factories expanded, so too did its labor force. By the 1920s, the population had swelled to over 100,000, fed by internal migration from the countryside and the wider Soviet sphere. This influx produced a new artistic subject: the worker. The emerging genre of industrial realism—nurtured by both necessity and ideology—found fertile ground in Mariupol, even before the term “Socialist Realism” had entered official discourse.

Painters with no formal training began to depict their peers in action: stoking furnaces, repairing gears, hauling ore. These early works were crude by academic standards, but they had urgency, grit, and a palpable materiality. In some cases, they functioned as collective portraits, with names written on the reverse—tributes not to an ideal, but to specific individuals. One such work, a 1924 oil painting known as Steel Shift, now lost but documented in photographs, depicted seven men eating together beneath a girder scaffold, their boots blackened, their shirts soaked. The artist, Petro Kovalenko, a former metalworker turned night-school student, insisted the painting was not propaganda but “for memory.”

These worker-artists often operated in informal circles, showing their work at factory clubs, trade union halls, and community centers. The line between documentation and expression was blurry. Technical diagrams were annotated with flourishes; production reports bore sketched margins. This grey zone between utility and art gave rise to a quiet movement—a vernacular realism that defied both avant-garde abstraction and state-sponsored triumphalism.

At the same time, visiting artists from Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Odessa began to take interest in Mariupol as a subject. Their work, often commissioned by industrial journals or state institutions, attempted to reconcile the human cost of labor with the spectacle of steel. One remarkable lithograph by Vsevolod Bazhenov in 1931 shows a shift change at Azovstal, with bodies arranged almost like musical notes across the factory grounds, framed by plumes of white steam and cranes shaped like crucifixes. Though officially aligned with Soviet themes, Bazhenov’s work betrays an ambivalence—a sense that the industrial sublime was not merely progress, but a kind of sacrament with its own rituals and martyrs.

Private Studios and Public Statues in a Company Town

Despite the increasing ideological oversight of the arts, the interwar period in Mariupol saw the emergence of private studios—often run by self-taught artists, teachers, or veterans of the Russian Civil War. These spaces, hidden in basements or above workshops, offered training in drawing, sculpture, and composition. Materials were often improvised: scraps of iron from the mills, pigment made from coal ash, canvases stretched from recycled tarpaulins. Yet the instruction was serious, and some of these students would later enter regional art schools or become professional illustrators.

These studios also gave rise to a new type of sculpture: small metal or clay figures representing workers, sailors, and factory tools. While some were commissioned by trade unions or youth organizations, others were made privately as gifts, trophies, or memorials. A recurring theme was the “blacksmith of socialism”—a hyper-muscled figure with a hammer and raised arm. But more intimate works also appeared: busts of mothers, children in heavy coats, miners bent over lamps. These pieces rarely left the city, but they populated its homes, schoolrooms, and public spaces like folk relics of an emerging civic mythology.

In parallel, the city’s authorities began to install public monuments, beginning with busts of local revolutionary figures and plaques honoring early Bolshevik organizers. One of the earliest large-scale statues was a monument to the October Revolution, erected in 1927 in what is now known as Theatre Square. Cast in iron by a team of foundry workers and art students, it featured a stylized hand gripping a gearwheel—an almost cubist gesture toward unity and labor. Though destroyed during the German occupation in the 1940s, fragments of the original base survive, now incorporated into a later postwar memorial.

- During this era of industrial expansion, three visual motifs became foundational to Mariupol’s emerging aesthetic:

- Verticality: Chimneys, cranes, and scaffolds came to define the city’s skyline and iconography.

- Anonymous Bodies: Workers were depicted as collective types rather than individuals, emphasizing mass over self.

- Material Texture: Iron, soot, grease, and dust were rendered with increasing fidelity, grounding the art in physical reality.

This visual language—born of steel and sweat—became Mariupol’s vernacular. It was shaped by those who lived within its logic: the rhythm of shift changes, the glare of molten slag, the fatigue etched into every surface. As the Soviet era advanced, these images would be appropriated, refined, and eventually monumentalized—but their roots lay here, in the sketches and scraps of a city learning to see itself in smoke and iron.

Between Revolution and Ruin: 1917–1930s Cultural Tumult

Avant-Garde Sparks in a Provincial Port

The Russian Revolution of 1917 fractured the cultural terrain of Mariupol as surely as it did its political and economic order. The city changed hands multiple times between Red, White, and anarchist forces during the ensuing civil war, each regime bringing its own visual imperatives—banners, proclamations, painted slogans, and acts of iconoclasm. But amid the confusion, a brief and potent window opened in which avant-garde ideas filtered into Mariupol from Moscow, Kharkiv, and beyond, carried by agit-trains, pamphlets, and itinerant artists seeking a revolutionary periphery where new forms could take root.

Though Mariupol never became a hub of high modernism, its proximity to Donetsk and the industrial arts institutions of Kharkiv meant that it did not remain isolated. Constructivist and Suprematist aesthetics—geometric abstraction, collage, and utilitarian design—began to appear in posters, educational illustrations, and agitprop installations. One of the earliest known examples is a 1920s mural painted in the entry hall of a youth club near the port. Long since destroyed, it was documented in a surviving sketchbook by Vasyl Mylovanov, a student from Kharkiv, and shows a composition of concentric circles intersected by steel beams and Cyrillic slogans: “Work Is the Rhythm of History.”

These early experiments were often ephemeral, tied to festivals, parades, or literacy campaigns. Yet they marked a shift in visual language—from devotional symbolism and naturalism to abstraction and purpose. Art was no longer a reflection of the divine or the real; it was a tool, a signal, an engine. Schools and workshops began to teach graphic design and typography alongside more traditional drawing. Artists were encouraged to see themselves as engineers of perception, not solitary visionaries.

In one striking instance, a theater troupe affiliated with the Proletkult movement staged a 1924 production of The Man Who Was Thursday, adapted to reflect the revolutionary paranoia of the day. The set—assembled from scrap metal, scaffolding, and painted panels—was designed by a local carpenter and two factory artists who had never before seen a Constructivist stage. Photographs suggest an aesthetic closer to German Expressionism than Soviet orthodoxy, a reminder of how porous cultural borders remained before Stalinist formalism locked them down.

The Fate of Icon Painters and Artisans Under Soviet Rule

For all its revolutionary fervor, the 1920s also witnessed the violent unmaking of the visual world that had defined Mariupol’s previous century. Churches were closed, icons confiscated, and religious artifacts either destroyed or absorbed into state-run museums as examples of “primitive” art. The very artists who had once been central to community life—the icon painters, gilders, embroiderers—found themselves dismissed, surveilled, or quietly reclassified as decorative workers in state ateliers.

Many of these artisans attempted to adapt. Some began producing “secular icons” for civic buildings: portraits of Lenin, heroic renderings of factory scenes, idealized depictions of peasants. The stylistic continuity with their earlier work was uncanny—halos replaced by radiant gearwheels, saints by political martyrs. A handful found employment in workshops that produced propaganda panels, school maps, or painted banners for May Day parades.

Yet others refused or were unable to adapt. Several older iconographers—among them the respected painter Theodoros Karidopoulos—simply ceased working. Oral histories preserved by their descendants describe the slow removal of brushes from shelves, the grinding of leftover pigments into dust, the covering of once-revered icons with linen or old coats. This cultural eclipse did not happen all at once, but it was deliberate and totalizing. What had once been seen as divine labor was now treated as superstition or sedition.

- Some surviving works from this transitional period betray the tension:

- Hybrid Icons: One unsigned painting from 1927 shows a robed figure holding a sheaf of wheat and a gear—Saint or Stakhanovite?

- Overpainted Canvases: In several village churches, traditional frescoes were whitewashed and replaced with state emblems, only to reemerge decades later when plaster peeled.

- Smuggled Fragments: Pieces of icon screens and crosses were embedded into furniture or reused in cryptic ways—altar panels turned into cupboard doors, gospel covers remade as jewelry.

These fragments are neither wholly sacred nor profane. They represent a shattered aesthetic continuity, with each object carrying the weight of disavowal. In the space where icons once guided the eye, posters and portraits now dictated attention. And yet, some of the older visual habits—symmetry, frontal address, vertical emphasis—persisted in unexpected ways, seeding the future even as the past was officially erased.

First Museums and Art Schools: Institutions in the Making

Amid this ideological and aesthetic upheaval, Mariupol saw the birth of its first formal art institutions. The most significant was the creation of the Mariupol Local History Museum in 1920, a civic project initiated by a small group of teachers, veterans, and amateur archaeologists. Though its initial focus was ethnographic—folk costumes, coins, agricultural tools—it quickly amassed a collection of local icons, crafts, and portraits donated or seized during the campaign against religious art.

The museum’s early curators walked a delicate line. On one hand, they echoed official discourse by labeling traditional items as “relics of feudal superstition.” On the other, they preserved these objects with a care that belied mere condescension. Archival letters reveal curatorial debates over how to classify a 19th-century Greek iconostasis—should it be displayed as religious art, colonial artifact, or ethnic folklore? The compromise was often semantic: sacred became “cultural,” beauty became “form,” devotion became “function.”

In the same period, the city opened its first technical drawing school, later expanded into a vocational institute for decorative and applied arts. Here, working-class youth learned to draw blueprints, design signs, and assemble propaganda posters. While these skills were intended to serve industry and ideology, they laid the groundwork for a generation of artists who would later emerge with more personal or subversive voices.

One notable graduate, Yelena Honchar, began as a sign painter for the steel works but went on to create large-scale public murals blending industrial motifs with ancient steppe imagery—stylized horses, solar discs, grain stalks. Though these works conformed to state requirements in form, they smuggled in a vocabulary far older than the revolution.

By the end of the 1930s, Mariupol’s visual culture had been remade: the icons hidden, the churches shuttered, the sacred repurposed, the artisanal pressed into service of the industrial. And yet, beneath this surface, older rhythms lingered in gesture, composition, and memory. The city’s aesthetic history—like its political one—was no longer linear. It had become a palimpsest of ruptures and returns, a place where each new image carried the echo of those erased before it.

War, Erasure, and Memory: The World Wars in Mariupol’s Visual Culture

Artistic Responses to Destruction and Occupation

The World Wars struck Mariupol not merely as military catastrophes but as profound cultural dismemberments. Each brought a wave of physical destruction and ideological inversion that reshaped the city’s built environment, its artistic institutions, and its capacity to remember itself through visual means. In both conflicts, art functioned not only as documentation but as resistance, grief, and, eventually, controlled narrative.

During World War I, the city’s cultural life was already in retreat, constrained by shortages, conscription, and censorship. Mariupol’s modest art school shuttered by 1916, its instructors either drafted or reassigned to logistical posts. Icon painters had already been sidelined by secular commissions, but now even secular art had to align with wartime needs. Civic spaces were stripped of decoration to accommodate military use; churches were requisitioned as warehouses or infirmaries. What few artistic expressions emerged did so in fragmentary, often private forms—diary sketches, embroidered memorials, grave carvings. These were intensely local, humble gestures of mourning and endurance.

The Second World War was far more devastating. Between 1941 and 1943, Mariupol was occupied by the German military and placed under the control of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. The occupation brought mass executions, the deportation of Jews and political dissidents, and the suppression of all Soviet-affiliated culture. Artists were given stark choices: collaborate, go silent, or flee. Many chose silence. A few vanished into labor camps or partisan resistance.

And yet, even under occupation, images circulated. Propaganda posters appeared in German and Ukrainian, produced in workshops staffed by coerced labor. These posters often used crude caricature, gothic lettering, and nationalist imagery—sunrises over wheat, idealized peasants, anti-Bolshevik tropes. Against them, resistance artists began to produce clandestine counter-images. Hand-drawn leaflets, pasted in alleyways at night, featured martyr portraits, burning factories, or single words—Pomsti (“Avenge”). Most of these pieces were quickly torn down or destroyed, but a few have been preserved in underground archives or private collections.

One particularly powerful image, recovered from a destroyed house in 1944, shows a kneeling figure with their face obscured, drawn in charcoal on the interior wall of a basement. It bears no caption, but beneath it was found a date—1942—and a name: Irina D. Whether this was an artist’s self-portrait, a mourning gesture, or a record of arrest remains unclear. But its ghostlike presence reminds us that war-era art in Mariupol often lived where formal history refused to look—in the margins, in the ruins, in the unrecorded gestures of the besieged.

National Socialist Bombings and Cultural Loss

The material toll of the Second World War on Mariupol’s cultural infrastructure was severe. By the time the Red Army retook the city in 1943, more than half its residential buildings had been damaged or destroyed, including most of its churches, several 19th-century civic buildings, and virtually every public sculpture erected before 1939. The city’s main museum, which had housed local archaeological finds, folk art, and a small collection of paintings, was looted and burned. Eyewitness accounts describe icons being used as firewood, bronze busts of revolutionary figures melted down for scrap, and murals covered in whitewash or destroyed by shrapnel.

Among the greatest artistic losses was the near-total destruction of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin. Built in the 1800s, it had housed one of the last surviving iconostases painted by Mariupol’s Greek school in the old style. Photographs taken in the 1930s show it still intact: golden panels crowded with saints, bordered by grapevines and stylized meanders. After the war, only charred beams and a single panel—depicting St. George—were recovered. That panel now resides in a regional museum in Dnipro, its original provenance often unmentioned.

The bombing of Mariupol also erased countless private artworks. Diaries, sketchbooks, textiles, and family icons—objects that lived outside the purview of official culture—vanished with the houses that contained them. For many families, art was not recoverable through insurance or reconstruction. It was memory’s infrastructure, and once gone, it could not be rebuilt.

Yet some images endured, often in unexpected forms:

- Prison Camp Drawings: A handful of pencil sketches from Mariupol residents deported to labor camps in Germany survived, depicting barracks life, guards, and dreamlike visions of home.

- Graffiti in Shelters: Layers of drawings—names, flowers, crosses—discovered in postwar inspections of bomb shelters and cellars, scratched or painted during air raids.

- Hidden Icons: Several families buried or boarded up icons during the occupation. Decades later, restorers found them embedded in walls or hidden in attics, wrapped in newspaper or linen.

These objects were not merely survivors; they were interruptions in the narrative of total loss. In a city where both ideological purges and enemy fire had aimed to erase visual history, such fragments were acts of defiance.

Commemorative Art and the Problem of Silence

After 1945, Mariupol, like much of the Soviet Union, entered a period of reconstruction that was as aesthetic as it was infrastructural. Art was enlisted to build memory, to guide mourning, and to instruct the public in how—and what—to remember. This meant monuments, murals, and staged images that aligned personal grief with national myth.

The earliest commemorative projects in Mariupol were modest: plaques honoring war dead, busts of fallen officers, temporary installations for Victory Day parades. By the late 1940s, however, a more orchestrated visual strategy emerged. Artists were commissioned to design war memorials that avoided ambiguity. The dead were heroic, the sacrifice collective, the enemy abstract. One central piece, unveiled in 1952 in the city’s Victory Park, showed a Red Army soldier with a child in one arm and a rifle in the other—based loosely on Berlin’s Soviet War Memorial. It was a work of symbolic clarity, devoid of local specificity.

This state-sponsored clarity, however, masked a deeper visual silence. Nowhere in these monuments were the deported Jews of Mariupol mentioned. Nowhere were the destroyed churches acknowledged, or the private losses of cultural artifacts addressed. The war’s aesthetic memory was shaped not by what was felt, but by what was permitted to be seen.

A small number of local artists resisted this flattening. In the late 1940s, graphic artist Dmytro Rudenko produced a series of woodcuts titled Ruins and Remnants, which were never publicly exhibited but circulated privately among friends and students. These stark, black-and-white images showed broken staircases, collapsed domes, faces made of shattered bricks. One print, Wailing Wall—Mariupol, subtly referenced the Jewish cemetery destroyed during the occupation. Though Rudenko was later forced to recant and cease producing “morbid and unheroic” work, his images have since reemerged as crucial documents of wartime visual truth.

By the early 1950s, Mariupol’s official visual culture had stabilized into the idiom of Soviet realism: murals of reconstruction, portraits of workers, cityscapes cleansed of trauma. But beneath this surface ran a substratum of memory-images—hidden, partial, smuggled—preserving what could not be said aloud. They would remain dormant until later generations returned to the ruins not only to rebuild, but to remember.

Postwar Reconstruction and Socialist Realism

Art Under Stalin’s Shadow: Public Monuments and Approved Styles

The aftermath of World War II placed Mariupol under the architectural and ideological regime of Soviet reconstruction. The city, bombed and hollowed, was to be rebuilt not just as a functional port and industrial node, but as a visual demonstration of Soviet resilience. That meant a total aesthetic reinvention—one designed to erase both the ruins of war and the ambiguities of memory, replacing them with grandeur, clarity, and control. Art, in this context, was no longer a medium of individual vision or community reflection; it was a tool of state choreography.

Under Stalin’s direct influence and later through the mandates of the USSR’s Committee on Art Affairs, Mariupol entered the era of Socialist Realism with full compliance. The visual logic of the new art was rigid: it must be optimistic, heroic, and intelligible. Factories were temples of labor. Workers were Titans of progress. History was linear, purposeful, and unclouded by contradiction. This was a significant departure from the layered, often hybrid visual traditions Mariupol had fostered in earlier decades. Now the city’s art was to speak with a single voice, loudly and without irony.

New public monuments emerged across the city, most notably in squares and factory zones. One of the first major commissions was a statue of Joseph Stalin himself, erected in the city center in 1949. Sculpted by a team from Kyiv and cast in bronze at the Azovstal plant, the statue stood three meters tall and portrayed Stalin in long coat, arm outstretched—not as an individual, but as the personification of the state. Though dismantled after his death, photographs show it dominating the skyline in a way no prior monument ever had.

This grandiosity extended to architectural ornament. Buildings reconstructed under the so-called “Stalinist Empire style” bore columns, medallions, and heroic friezes. The House of Culture, rebuilt in 1951, featured a stage framed by bas-reliefs of dancers and steelworkers, and a ceiling painted with allegorical scenes of peace and production. Mariupol’s railway station and main post office were adorned with panels in plaster and terrazzo that depicted smiling miners, red banners, and neatly gendered images of progress: women with books, men with hammers.

What disappeared in this transformation was ambiguity. Prewar art that had once captured the tensions of identity—Greek, Ukrainian, Russian—or the subtleties of folk symbolism, was now suppressed under a visual grammar of order and triumph. In the city’s museums and public exhibitions, even historical figures were recast. A 1953 portrait of Cossack hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, for instance, showed him flanked by smokestacks and power lines—anachronistic, but ideologically neat.

Factory Murals and the Visual Myth of Progress

Mariupol’s factories were not only engines of production but stages for artistic performance. Throughout the 1950s and 60s, artists were commissioned to paint murals, mosaics, and banners inside industrial facilities, worker dormitories, and canteens. These images served as daily reminders of collective purpose. They were also, in a more insidious sense, part of the sensory infrastructure of control—making visible the state’s version of truth wherever the worker turned his or her head.

One of the most ambitious of these projects was the mural cycle in the main assembly hall of the Illich Steel and Iron Works, completed in 1957 by the painter Mykola Shelest. Stretching over 15 meters in length, the mural depicted the “History of Metal” from Prometheus to Sputnik. It opened with mythological scenes rendered in a Soviet classical style—glowing figures with muscular torsos forging iron—before transitioning into an industrial panorama: blast furnaces, welding sparks, workers shaking hands with cosmonauts. The composition was seamless, its chronology fantastical, its message unmistakable: Soviet labor was eternal, transcendent, and victorious.

Smaller murals proliferated in cafeterias, training centers, and housing complexes. A common motif was the worker-hero in profile, eyes fixed on a distant horizon, framed by wheat sheaves and red banners. Women were often shown teaching, nursing, or harvesting; children played at the feet of engineers. These images formed a kind of civic catechism, repeated across surfaces until they became part of the mental landscape.

And yet, within this flood of formulaic optimism, some artists found room for subtle variation. A mosaic in a Mariupol maternity hospital, dated 1962, showed mothers and infants surrounded not by factories, but by stylized sea waves, sunflowers, and doves—an echo of older decorative traditions. Though still ideologically safe, the work revealed a flicker of individuality and regional sensibility. Likewise, some technical illustrators—tasked with drawing diagrams or safety posters—added personal touches: initials, jokes hidden in margins, whimsical animals sketched behind pipes and conduits.

- These decorative works, though constrained, displayed certain recurring strategies of covert expression:

- Micro-Variation: Artists subtly altered standard poses or motifs to introduce personality or wit.

- Symbolic Displacement: Non-political imagery—plants, waves, geometric patterns—offered aesthetic relief from ideological overcoding.

- Survival of Craft: Traditional techniques, like sgraffito and stained glass, persisted in new ideological frames.

The result was a double register of visual experience: one overtly heroic and doctrinaire, the other quieter, latent, still haunted by older artistic instincts.

Institutional Control and Regional Exceptions

As Soviet cultural policy became more centralized under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, the boundaries of acceptable expression narrowed even further. Art institutions in Mariupol, now renamed Zhdanov in honor of Stalin’s close ally, were directly governed by Kyiv’s cultural organs and subject to strict ideological vetting. Exhibitions had to be pre-approved; artists had to join the Union of Soviet Artists to work legally. Themes were prescribed: peace, labor, progress, youth. Styles were monitored. Deviations could result in career destruction—or worse.

Despite this, Mariupol maintained a few regional exceptions. The city’s School of Decorative and Applied Arts, while primarily vocational, became a quiet haven for experimentation in design and form. Instructors who had trained in Lviv or Tbilisi brought influences from outside the dominant Moscow-Kyiv pipeline: folk motifs, textile techniques, and regional color theories. Their students produced ceramics and tapestries that, while politically neutral, hinted at alternative visual worlds.

One such artist, Lyudmyla Tsehelko, became known for her enamel panels that depicted steppe flora and sea creatures in swirling, semi-abstract forms. Officially classified as “decorative craft,” her work avoided direct political symbolism and thus escaped censure. Yet its departure from the muscular realism of state murals was unmistakable. Her pieces, installed in libraries and kindergartens, offered glimpses of beauty untethered from ideology.

The city’s cultural life during this era was thus marked by a stark duality. On one hand, monumental propaganda art saturated public space with prescribed meaning. On the other, a quiet undercurrent of aesthetic autonomy persisted—in textiles, ceramics, marginal illustrations, and the decoration of spaces deemed ideologically secondary. It was not open rebellion, but a form of slow resistance—a refusal to let the image collapse entirely into the state.

In this, Mariupol’s postwar art did not simply reflect the Soviet project; it absorbed, deflected, and in some cases, gently reshaped it. Its murals and monuments may have glorified the Five-Year Plans, but beneath their surfaces, fragments of older artistic languages still flickered—sometimes invisible to the regime, sometimes barely visible to the viewer, but always there, waiting.

The Underground Current: Nonconformist and Marginal Art

Artists Who Rejected the Official Canon

By the 1970s, Mariupol’s visual culture appeared on the surface to be in complete alignment with Soviet orthodoxy. Murals celebrated harvests and steel production, statues reinforced approved heroes, and exhibitions displayed flawless renderings of idealized workers. But beneath this surface compliance, a quiet revolt had begun—carried out not in open defiance, but in careful avoidance, displacement, and disguise.

The city’s underground art scene never formed a unified movement. It was composed of scattered individuals and small groups—teachers, engineers, poets, retired craftsmen—who used what tools they had to create outside the sanctioned system. They were not gathered under a manifesto or recognized school; their unifying trait was refusal. Refusal to join the Union of Soviet Artists. Refusal to paint smiling factory workers. Refusal to reduce vision to orthodoxy.

One of the earliest documented nonconformist figures in Mariupol was Oleksandr Kulchytskyi, a trained architect who painted at night in his apartment. His surviving canvases, almost all under 50 cm, feature desolate factory corridors, flooded stairwells, and solitary figures trapped in spaces of distorted perspective. They carry no political slogans, yet each is a quiet negation of Socialist Realism’s optimism. In one work, Untitled (1976), a worker in a yellow helmet gazes into a black void that occupies nearly half the canvas. The figure is technically precise, but the composition breaks every rule of the “positive image.”

Kulchytskyi exhibited once—briefly, in a basement apartment in 1978—before being warned by authorities and pressured into abandoning his work. He returned to design work for the local housing board and left his paintings hidden. After his death in 1990, his nephew discovered nearly 80 canvases stacked behind false panels. A small selection was later shown, quietly, in a post-Soviet gallery.

Others found subtler ways to resist. Some worked within applied arts—ceramics, textile design, signage—infusing decorative forms with surreal or archaic motifs that slipped past ideological screening. Anonymity was both protection and necessity. One local weaver, known only as “Lena from Kalmius,” produced rugs with geometric figures and cryptic symbols that recalled Scythian and Sarmatian visual traditions. Her work, sold at craft fairs, was interpreted as folkloric. Few recognized that some of her symbols—interlocking circles, severed vines, crescent moons—also appeared in banned books of esoterica and were quietly passed between artists as visual code.

This generation of nonconformists was marked not by confrontation but by endurance. Their work was not revolutionary in style—often it was muted, fragmentary, unfinished. But it stood in opposition simply by existing: an image painted for its own sake, a vision unaligned with orders.

Samizdat, Private Exhibitions, and Coded Symbols

In Mariupol, where formal galleries were rare and state institutions suspicious, the private apartment became a gallery, archive, and sanctuary. Known as kvartirniki, these gatherings were part exhibition, part salon, part act of trust. Artists would show small paintings, collages, or graphic experiments; poets would read from handwritten manuscripts; musicians played tape-recorded ballads banned from radio.

One such gathering in 1983—described in a surviving diary by attendee Serhii Andrusenko—took place in a sixth-floor flat overlooking the port. The walls were hung with ink drawings on cardboard: surreal landscapes, disfigured saints, mechanical birds. The host, an unregistered painter named Yevhen P., passed around a sketchbook that contained a visual alphabet he had been developing—symbols drawn from Greek script, Cyrillic, and mathematical notation, designed to form hidden sentences within paintings. Guests interpreted them differently. Some saw poetry. Others saw mockery of the regime.

These informal gatherings were dangerous. Participants could be denounced. Work could be confiscated or destroyed. Yet they flourished, in part because they redefined the conditions of art-making. Without the need to appeal to official juries or committees, artists experimented with format, medium, and content. Collage became a favored form, especially using discarded newspapers, outdated textbooks, or packaging from Western imports smuggled in through the port.

One such collage, Notes on Silence (1985), attributed to a figure known only as “A.M.,” layered a portrait of Lenin—cut from a children’s reader—with anatomical diagrams and fragments of prayer text in Greek. It was never displayed publicly but circulated in photocopied reproductions, passed between students and artists. These reproductions—slightly blurred, degrading with each copy—formed a secondary art form in themselves: art as rumor, as ghost.

- Within this underground circuit, three key practices emerged:

- Replication: Works were often designed to be copied, mailed, or memorized—evading destruction by dispersal.

- Erasure: Visual absence—blank faces, crossed-out slogans—became a formal device and political gesture.

- Quotation: Symbols from banned texts, archaic alphabets, or religious iconography were used in composite images.

Such works did not merely reject the official canon; they rewrote it in shadow. For every triumphal mural or Lenin bust in the city center, there existed a parallel image—a hidden one, fragile and dissonant, alive in secret.

Tracing Dissident Aesthetics in a Minor City

Mariupol never produced a Sakharov or Brodsky. It was not a center of official dissent. But its artistic underground was shaped by the same tension that marked its geography: on the edge of empire, visible but peripheral, reactive but overlooked. This gave it an unusual strength—freedom born of neglect.

By the late 1980s, as glasnost spread, some of these marginal artists began to emerge into semi-public view. Local libraries hosted small shows of “folk” or “alternative” art. Youth groups printed chapbooks with linocuts or surreal drawings. A 1989 exhibition titled Voices from the Cellar at the House of Culture featured collages, zines, and graffiti-inspired paintings by young artists who had grown up amid stagnation, war memory, and whispered defiance.

Yet even then, many of the older nonconformists remained wary. They had spent decades painting in silence, burying sketchbooks, passing around coded works with the knowledge that a single denunciation could unravel their lives. For them, perestroika was not liberation—it was ambiguity. Some refused to show their work even after 1991, believing the conditions for true independence had not yet arrived.

A few exceptions stand out. The painter Halyna Kosach, who had lived in obscurity since being expelled from the Kyiv Art Institute in 1969, held a solo show in Mariupol in 1993. Her paintings, stored for decades in a damp garage, featured abstracted steppe landscapes filled with disjointed mythological figures: a dismembered Persephone, a one-eyed falcon, saints with missing hands. Critics dismissed them as eccentric; others recognized in them the buried trauma of empire and erasure.

These were not marginal works by accident. They were marginal by design, by history, by necessity. They offered no final judgment, no synthesis. They were footnotes made of paint, and yet they spoke more truly than the monuments in the square.

Perestroika and Reawakening: Late Soviet Mariupol

The 1980s Local Renaissance and Experimental Collectives

By the early 1980s, something long suppressed began to stir in Mariupol’s cultural core. Though still officially called Zhdanov—a name imposed in 1948 to honor Stalin’s ideologue Andrei Zhdanov—the city was shifting underfoot. Political stagnation had bred apathy, but also a quiet hunger for meaning, authenticity, and aesthetic possibility. As the Soviet system entered its twilight, artists in Mariupol began to test the boundaries of what could be seen, made, and said. The result was a fragile, unpredictable, and often brilliant reawakening.

The clearest signs came not from state institutions but from collectives—small, independent circles of artists, writers, and performers who began to organize shows, performances, and collaborative projects outside official parameters. Many were based in cultural palaces or factory clubs, using their institutional cover to pursue unofficial goals. One such group, Rytmy (“Rhythms”), formed in 1984 and consisted of painters, textile designers, and musicians drawn to abstraction, improvisation, and mysticism. Their first unofficial show was held in a defunct boiler room behind the House of Maritime Workers, lit with floodlamps and scored by experimental tape loops. The paintings—semi-abstract visions filled with geometric forms and natural motifs—were unlike anything Mariupol’s cultural authorities had seen in public before.

Another group, Oberih, focused on reviving folkloric and pagan imagery suppressed or ignored during Soviet decades. Their members stitched ritual garments, carved talismans, and painted symbolic landscapes meant to reconnect with pre-Christian steppe cultures. Though their practice was not overtly political, it subtly rejected the ideological frameworks of Marxist history and materialism, asserting instead a vision of cultural time that was cyclical, mythic, and rooted in land and ancestry.

These collectives didn’t only exhibit—they gathered. Weekly meetings, tea circles, silent film screenings, and shared sketchbooks became rituals. They allowed for the exchange of images, ideas, and questions. What does Ukrainian art look like after decades of Soviet filtration? Can a port city reclaimed by Greeks, industrialized by empire, and silenced by ideology find its own symbolic voice? These questions weren’t always answered, but they animated a generation of artists who came of age with one foot in suppression and another in ambiguity.

Though still shadowed by censorship, cracks had appeared. Glasnost, announced in 1986, loosened restrictions on cultural expression. Previously banned books—on philosophy, history, art—began circulating in pirated copies or returned to libraries. New vocabulary entered the artist’s studio: “identity,” “memory,” “language,” “trauma.” Even state curators grew more lenient, allowing exhibits that just a few years earlier would have been pulled from walls or locked in basements.

New Spaces for Art and Public Discourse

Architecture and urban space in Mariupol also began to reflect this shift, albeit unevenly. The House of Culture, once a stage for ideological pageantry, began to host more eclectic exhibitions and performances. In 1987, it mounted a show titled Shadows and Echoes, featuring installations and large-format drawings by local artists interpreting the myths of Scythian burial mounds and Sea of Azov folklore. The show had no overt political message, but its embrace of loss, burial, and non-linear time spoke volumes in a city where so much had been suppressed or erased.

Unofficial galleries began to emerge in adapted spaces—warehouses, stairwells, attics. A metal shipping container near the port became an ad hoc gallery for student work. The city’s university opened its printmaking workshop to non-students, allowing artists to create monotypes and etchings after hours. These spaces, though often short-lived, were experimental laboratories. They were less concerned with audience or market—there was no market to speak of—and more with reclaiming the right to create without permission.

One particularly influential venue was the “Blue Corner,” a name given to a converted apartment hallway painted in faded indigo and used for readings, installations, and zine distribution. Artists hung textiles from ceiling pipes, tacked drawings to cracked plaster, and wrote poems on the walls in chalk. The space became a crucible for Mariupol’s emerging alternative scene, hosting everything from silent film revivals to punk performances to icon-making workshops that blended Orthodox tradition with anarchic collage.

This burst of activity coincided with a slow, uneven reclaiming of the city’s original identity. Although still officially named Zhdanov, artists and cultural workers increasingly referred to it by its historical name, Mariupol. By the late 1980s, this reversion became a subject of art itself. One exhibition in 1989 featured posters reading “Zhdanov Is a Scab. Mariupol Is a Wound.” Another installation—a reconstructed icon corner made of rusted steel and photographic scraps—juxtaposed the language of Soviet materialism with the symbolic detritus of memory. The message was clear: the city’s history, long buried beneath ideology and steel dust, had started to breathe again.

Murals, Posters, and the Reclaiming of Greek-Ukrainian Identity

This reawakening brought with it an urgent exploration of Mariupol’s Greek roots—a subject long buried beneath Soviet policies of Russification and religious erasure. Artists and writers began to unearth family histories, village myths, and the visual traditions of their Crimean Greek ancestors. Church murals, textile motifs, and village architecture became sources not of nostalgia, but of creative provocation.

Murals emerged on the outer walls of schools, factories, and abandoned kiosks—unofficial, often painted without permission, and frequently removed within days. One striking example from 1988, by the painter Iannis Petropoulos, portrayed a processional of saints and factory workers merging into a single river, flanked by fig trees and smoke stacks. The faces were rendered in the icon style—elongated, luminous—but their halos contained gears, wheat, and sea waves. It was both satire and reverence, a reassertion of cultural layering that refused ideological purity.

Posters became another vital form. Silk-screened or stenciled at night, these images often bore slogans in Greek and Ukrainian, sometimes mixed with Russian to emphasize the city’s hybridity. A recurring image was that of the lost church—a silhouette overlaid with fingerprints or tears. Others featured portraits of unnamed women or fishermen, identified only by dates and initials. These posters were glued to tram stops, factory gates, and cultural centers. Most were torn down quickly, but they persisted in memory and in photograph.

Artists also began to revive liturgical forms—triptychs, ex-voto offerings, and processional banners—not as religious artifacts but as artistic formats. In one 1989 installation, three panels displayed scenes from Mariupol’s history: the Greek resettlement of 1778, the steel mill construction of 1896, and a grainy photo of a wartime execution. Each panel was painted in egg tempera on wood, evoking Byzantine technique, but the compositions were fractured and overlapping, as if to reject linear history altogether.

- This late-Soviet cultural moment fused multiple lines of inquiry:

- Historical Excavation: Art became a means of recovering suppressed identities, from the Crimean Greek to the Orthodox to the marginal.

- Spatial Reclamation: Public and domestic spaces alike became canvases for unsanctioned memory and expression.

- Aesthetic Hybridization: Traditional formats—icons, banners, murals—were remixed to speak in new, defiant tongues.

In these final years before the collapse of the USSR, Mariupol experienced what can only be described as a brief artistic renaissance. It was modest in scale, informal in structure, and fragile in its foundations. But it was real. For the first time in decades, artists no longer painted for the state or hid from it. They painted for each other, for their city, and for the hope that memory and imagination could still matter—even in a place that had tried for so long to silence both.

After the Fall: 1991–2013 and the Search for a Civic Aesthetic

The Collapse of Patronage and the Rise of Artist-Entrepreneurs

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought freedom, but not stability. Mariupol, like much of Ukraine, faced a sudden vacuum of institutional support, economic security, and cultural direction. The ideological certainties of the past had crumbled, but nothing yet stood in their place. For artists, this was both a liberation and a crisis. The state no longer dictated content—but it also no longer paid commissions, funded exhibitions, or maintained the bureaucratic infrastructure that, however controlling, had once sustained visual culture.

In this uncertain landscape, many artists turned to survival strategies. Some became entrepreneurs, selling landscape paintings, religious icons, or portrait sketches at street fairs and tourist markets. The aesthetics of these works varied wildly—impressionistic views of the Azov Sea, oil-painted Orthodox saints, romanticized peasant scenes. These were not acts of artistic compromise so much as reinventions. A generation that had been trained under ideological constraint now adapted its skills to a market that was volatile, sentimental, and deeply nostalgic.

Others moved into commercial art and design, forming small studios that offered logos, signage, or decorative panels for new businesses. The privatization wave swept through Mariupol with uneven speed, creating a patchwork of new commercial spaces—cafés, casinos, pharmacies—each hungry for imagery. Artists who once painted murals of steelworkers were now creating faux-Greek friezes for restaurants, airbrushed panoramas for children’s clinics, or grotesque cartoon mascots for discount shops. It was a strange, improvisational moment, in which aesthetic skill had to reattach itself to capital, taste, and speed.

Yet from this chaos, a new model emerged: the artist as self-directed creator, promoter, and curator. Some formed independent associations, pooling resources to rent studio space, publish catalogues, or travel to Kyiv and Lviv for group shows. One of the most active of these was AzovColor, a cooperative founded in 1995 that combined traditional painting with experimental media. Its members held rotating exhibitions in abandoned cultural halls and factories, often with installations made from scrap metal, sand, and construction debris. These shows rarely drew large audiences, but they created a vocabulary of Mariupol’s post-industrial moment—one that was tactile, fragmented, and defiantly local.

Local Galleries and Diaspora Engagement

Even amid financial instability, new institutions slowly emerged. In the late 1990s, Mariupol saw the founding of two small but significant galleries: Art-Pryazovia, located in a converted warehouse near the port, and Gallery Harbuz, run out of a former railway office. Both were independently operated, irregularly funded, and prone to closure, but each offered artists a chance to exhibit without ideological vetting or commercial packaging. Art-Pryazovia, in particular, championed regional identity, mounting shows that explored the legacy of Crimean Greek visual forms, local folklore, and maritime labor.

These spaces also facilitated engagement with the broader Ukrainian diaspora. Mariupol’s Greek-descended population had family ties in Greece, the U.S., and Canada, and some of these connections were leveraged for cultural exchange. In 2001, a traveling exhibition titled Sea, Iron, Icon included works from Mariupol artists shown alongside pieces from Greek artists in Thessaloniki and diaspora painters from Chicago. The thematic center was the Sea of Azov as both a border and a conduit—an image at once geographic and symbolic.

This transnational dialogue was not purely aesthetic. It opened Mariupol’s artists to new conversations about heritage, trauma, and cultural translation. For some, it rekindled dormant questions about language and faith; for others, it underscored the impossibility of return. Mariupol was not Odesa, nor Lviv, nor Kyiv. It was too far east, too industrial, too shaped by histories no longer fashionable in national discourse. And yet, that very marginality gave it a peculiar independence—a right to invent its own canon.

In 2006, Gallery Harbuz hosted a landmark group exhibition titled Port Without a Ship, in which each artist was asked to respond to the idea of cultural departure. The works ranged from melancholy seascapes to conceptual installations made of suitcases, rusted anchors, and burned books. A particularly haunting piece by Yevheniia Kostiuk consisted of a narrow corridor lined with mirrors and projected waves, over which a voice recited excerpts from lost letters. The show resonated deeply with Mariupol’s sense of fracture: not just geographic or economic, but symbolic—a city perpetually waiting to be reconnected with something larger than itself.

Conflict, Memory, and Art on the Margins of the Nation

Despite growing pluralism, Mariupol remained culturally isolated. National funding for the arts largely bypassed the city. Contemporary Ukrainian art discourse—centered in Kyiv, Lviv, and Dnipro—tended to ignore or stereotype the Donbas and Azov regions as culturally inert or politically suspect. Mariupol artists, in turn, felt ambivalent about their place in a national canon that seemed either indifferent or prescriptive.

This unease grew more pointed after 2004 and the Orange Revolution, which redefined Ukrainian identity in increasingly westernized and nationalist terms. Many in Mariupol, though supportive of democratization, felt alienated by cultural policies that privileged Hutsul folk motifs, western Ukrainian saints, or Central European modernism as “authentically Ukrainian.” For artists steeped in Greek Orthodox aesthetics, Soviet industrial memory, or multiethnic urban histories, these markers felt foreign—or at best, incomplete.

Some responded by doubling down on local themes. Painters returned to maritime labor scenes, steppe iconography, or the textures of post-Soviet decay: salt-scarred walls, graffiti over rust, abandoned cranes. Others turned inward, producing conceptual work that explored absence, entropy, or marginality itself. In one 2011 installation, artist Dmytro Bryhadin created a “Museum of Broken Plans” in a former machine shop, featuring shelves of incomplete drawings, melted VHS tapes, and cracked picture frames. A placard at the entrance read: Welcome to the edge of someone else’s map.

This peripheral status—economic, geographic, symbolic—became a source of artistic energy. It freed Mariupol from national expectations, allowing its artists to cultivate their own references, timelines, and critiques. But it also left them vulnerable. In a city whose identity had never fully stabilized, the absence of cultural infrastructure made recovery—of memory, of continuity, of vision—perpetually incomplete.

- By 2013, several core threads had emerged in Mariupol’s post-Soviet artistic identity:

- Post-Industrial Poetics: Artworks drew deeply from the textures, labor, and decay of a steel-based economy in decline.

- Cultural Layering: Artists embraced the Greek, Ukrainian, Russian, and Orthodox elements of their heritage as composite, not contradictory.

- Symbolic Exile: The city saw itself as estranged—not only from Kyiv or Moscow, but from its own past, perpetually searching for a stable self-image.

As Ukraine moved toward the Maidan uprising and the national reorientation that would follow, Mariupol stood at a crossroads it had long occupied: not one of clear allegiance, but of ambiguity, complexity, and unresolved inheritance. Its artists, like its citizens, bore that tension not as a burden, but as a practice—a daily act of negotiation with history, memory, and the unfinished image of the city itself.

War Comes Again: 2014–2022 and the Pressure of Violence

Donetsk’s Shadow and the Politics of Cultural Allegiance

The outbreak of war in eastern Ukraine in 2014 reshaped Mariupol with terrifying speed. As the Donetsk People’s Republic declared itself in the neighboring oblast, and Russian-backed separatists seized control of nearby cities, Mariupol found itself drawn into the gravity of a conflict it neither initiated nor fully understood. Though Ukrainian forces quickly reasserted control of the city in May 2014, the threat of siege remained constant. And with that threat came a profound shift in how culture, identity, and visibility operated within Mariupol’s already fragile civic space.

Art, in this moment, became political whether it wished to or not. The neutrality—or strategic marginality—that had allowed Mariupol’s artists to explore myth, decay, and ambiguity in the 1990s and early 2000s was no longer sustainable. In a city now framed by barbed wire and checkpoints, where each mural might be read as a signal of loyalty or dissent, every image became legible within the framework of conflict. The very act of painting on a wall, mounting an exhibition, or printing a slogan carried a new risk—and a new urgency.

Early signs of resistance emerged in small gestures. Artists painted the Ukrainian trident, or tryzub, on factory fences and over Soviet-era plaques. Yellow and blue stripes appeared on abandoned trolley cars, telephone poles, and sidewalks. These were not complex compositions; they were assertions of presence, of continued civic belonging in a city many feared could be lost.

Meanwhile, the long shadow of Donetsk’s cultural infrastructure loomed over Mariupol. Before the war, Donetsk had been the dominant artistic center in the east—home to large museums, concert halls, and avant-garde spaces. Its loss left a vacuum, both logistical and symbolic. Mariupol’s artists were suddenly expected to step into a leadership role for a region under siege. Many were unprepared for this visibility; others embraced it as a necessity.

Ukrainian cultural authorities, NGOs, and Western funders began arriving in Mariupol, eager to support initiatives that asserted national identity and civil society. New grants were issued. Murals were commissioned. Festivals were organized to mark the city’s resilience. Yet this influx came with complications. Some local artists—particularly those who had worked in ambiguity or nonalignment—found the new frameworks too narrow. The pressure to be “pro-Ukrainian,” though understandable, left little room for critique, grief, or the city’s Russian-language heritage.

Mariupol’s culture, once marked by layered ambiguity, was now thrust into a battleground of clarity. In the eyes of Kyiv, Europe, and the media, the city became a symbol of heroic resistance. But symbols have weight—and not all artists could or wished to carry it.

Art as Resistance, Testimony, and Survival

Despite these tensions, the war years also saw a flowering of civic art unlike anything in Mariupol’s post-Soviet history. For the first time, artists, activists, educators, and volunteers worked in close coordination to rebuild not just infrastructure, but a cultural vocabulary of survival. Art was not ornamental—it was integral. It soothed, warned, remembered, and redefined.

One of the most visible initiatives was the creation of public murals across the city, many facilitated by the Platforma TU and Big City Lab projects. These works—painted on housing blocks, clinics, and schools—often fused national symbolism with local reference. A 2017 mural near Theater Square showed a steelworker cradling a child, both framed by the sea and a rising sun patterned like a Trypillian ornament. Another, titled Roots, featured stylized depictions of Crimean Greek elders, their robes made of bricks and wheat, their eyes fixed on an unseen horizon.

These works were often collaborative, involving community members, students, and war veterans. The process became as important as the image: people painted not only to decorate, but to assert their presence in a city where daily life was marked by military convoys, sirens, and the anxiety of return.

- Several recurring themes defined Mariupol’s wartime art: