Mannerism was an artistic movement that emerged in the early 16th century, following the High Renaissance. It was characterized by elongated figures, exaggerated poses, unnatural colors, and complex compositions. Unlike the balance and harmony of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Michelangelo (1475–1564), and Raphael (1483–1520), Mannerist artists sought instability, movement, and artificial beauty. This movement was a direct response to the perfection of Renaissance art, introducing a more expressive, dramatic, and sophisticated style.

The origins of Mannerism can be traced back to Rome and Florence in the 1520s, following the death of Raphael in 1520 and the Sack of Rome in 1527. These events marked the beginning of a period of uncertainty, political instability, and shifting artistic ideals. Instead of imitating nature, Mannerist artists manipulated forms and perspectives, challenging traditional conventions. Over time, Mannerism spread across Italy, France, Spain, and Northern Europe, influencing architecture, sculpture, and literature.

This article explores the historical background, defining features, key artists, and the cultural impact of Mannerism. We will analyze the major figures, including Pontormo (1494–1557), Parmigianino (1503–1540), Bronzino (1503–1572), and El Greco (1541–1614). Additionally, we will examine how Mannerism evolved, its connection to the Counter-Reformation (1545–1648), and its transition into the Baroque style. By the end, readers will understand why Mannerism was a unique and highly influential artistic movement.

1. The Historical Context Behind Mannerism

Mannerism arose in the 1520s, during a time of political, religious, and cultural change in Europe. The Italian Renaissance (c. 1300–1600) had already reached its peak with the works of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael. However, after Raphael’s sudden death in 1520, many artists struggled to surpass the idealized beauty and balance of the High Renaissance. Instead, they began experimenting with more expressive, distorted, and intellectual approaches to art.

One of the defining events of this period was the Sack of Rome in 1527, in which the troops of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) pillaged the city. This event disrupted patronage and artistic production, forcing many artists to flee to Florence, Venice, and France. The instability of this period led to a shift in artistic themes, with increased tension, ambiguity, and psychological intensity. As a result, Mannerist artists focused more on personal expression than on adhering to classical ideals.

The Catholic Church also played a role in shaping Mannerism. The Protestant Reformation (1517–1648), initiated by Martin Luther (1483–1546), challenged the authority of the Pope and Catholic doctrine. In response, the Counter-Reformation (1545–1648) sought to use art as a tool for religious reinforcement and persuasion. Mannerist painters, particularly in Spain and Italy, produced artworks that emphasized spiritual intensity, dramatic compositions, and theatrical lighting.

Outside of Italy, Mannerism was influenced by the courts of France and Spain, where rulers sought to display power and sophistication through elaborate artistic commissions. In France, King Francis I (r. 1515–1547) invited Italian Mannerist artists to work at Fontainebleau Palace, creating the School of Fontainebleau (c. 1530–1580). In Spain, El Greco (1541–1614) combined Byzantine, Italian, and Spanish influences, producing some of the most expressive and spiritual Mannerist works.

2. Key Themes and Characteristics of Mannerist Art

Mannerism differed from the naturalism and balance of the High Renaissance by emphasizing artificiality, elegance, and complexity. Rather than aiming for realistic proportions and spatial harmony, Mannerist artists created elongated figures, exaggerated gestures, and intricate compositions. These distortions added a sense of drama, mystery, and movement to their works.

One of the most notable features of Mannerist art was the elongation of the human body. Figures often had graceful yet exaggerated poses, creating an unnatural sense of elegance. Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck (1534–1540) exemplifies this style, with the Virgin Mary depicted with an impossibly long neck and delicate fingers. This elongation symbolized divine grace and beauty, rather than adhering to realistic human anatomy.

Mannerist painters also used vibrant, unnatural colors to create a dreamlike, surreal atmosphere. Instead of the natural lighting and earthy tones of the Renaissance, Mannerist works featured harsh contrasts, vivid blues, pinks, and greens. Jacopo Pontormo’s Deposition from the Cross (1525–1528) demonstrates this technique, using bold color juxtapositions and weightless floating figures. This departure from naturalistic color schemes contributed to the mystical and dramatic quality of Mannerist paintings.

The use of crowded, complex compositions was another defining characteristic. Mannerist artists often packed their scenes with twisting bodies, dramatic gestures, and overlapping forms. El Greco’s The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586) is a prime example, featuring a swirling, chaotic arrangement of figures that blends the earthly and heavenly realms. These compositions often defied traditional perspective, creating an illusion of instability and movement.

3. The Great Masters of Mannerism

Several artists defined the Mannerist movement, each bringing a unique interpretation to its style. These figures pushed the boundaries of artistic expression, influencing later movements such as the Baroque (1600–1750).

Jacopo Pontormo (1494–1557)

- One of the earliest Mannerist painters, active in Florence.

- Known for emotional intensity, elongated figures, and vivid colors.

- Major work: Deposition from the Cross (1525–1528) – a floating, weightless composition with unnatural poses.

Parmigianino (1503–1540)

- Pioneered graceful, elongated forms and elegant distortions.

- Developed Mannerist portraiture, emphasizing refined and artificial beauty.

- Major work: Madonna with the Long Neck (1534–1540) – an iconic representation of Mannerist elegance and distortion.

Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572)

- Court painter to Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici (r. 1537–1574).

- Known for cold, polished portraits and complex allegories.

- Major work: Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time (c. 1545) – a mysterious, erotic, and intellectual composition.

El Greco (1541–1614)

- A Greek-born artist who worked in Spain, blending Byzantine, Venetian, and Spanish influences.

- Created highly expressive, almost surreal religious paintings.

- Major work: The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586) – a dramatic vision of heaven and earth, filled with elongated figures and mystical light.

4. Sculpture and Architecture in the Mannerist Movement

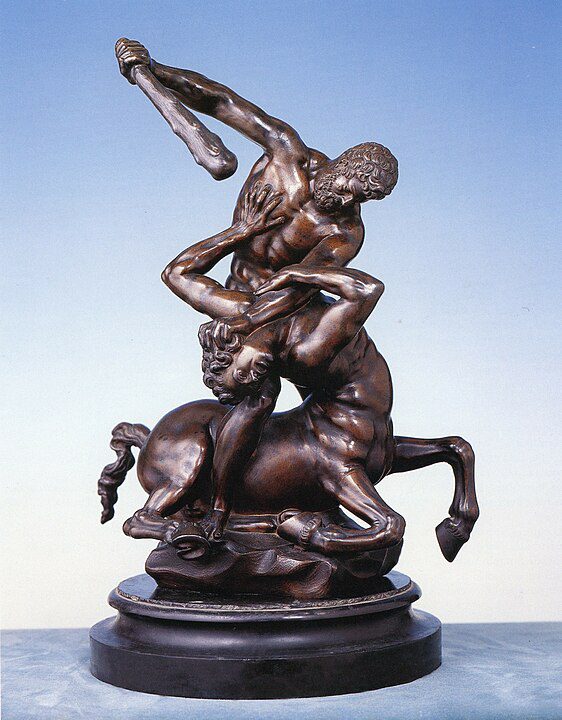

Mannerist sculpture moved away from the harmonious balance and naturalism of the High Renaissance, instead favoring elongation, tension, and dramatic movement. Figures became more twisted, exaggerated, and theatrical, often capturing a sense of instability and unease. Sculptors experimented with contrapposto poses, intricate surface textures, and emotional intensity to achieve a heightened sense of drama and complexity.

One of the most famous Mannerist sculptors was Giambologna (1529–1608), a Flemish artist active in Italy. His masterpiece, The Rape of the Sabine Women (1579–1583), features a spiraling composition where multiple figures interlock in a fluid yet chaotic struggle. Unlike Michelangelo’s Renaissance sculptures, which emphasized clarity and stability, Giambologna’s work conveys movement from every angle, forcing the viewer to walk around it for full comprehension.

Another key sculptor was Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571), known for his detailed and refined metalwork. His most famous piece, Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1545–1554), was commissioned by Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici for Florence’s Piazza della Signoria. The statue presents Perseus in a dramatic, twisting pose, holding Medusa’s severed head aloft with a sense of theatrical intensity. The intricacy of the bronze casting and exaggerated anatomy reflect Mannerism’s emphasis on technical skill and elaborate detail.

Mannerist architecture also broke away from the strict classical symmetry of the Renaissance, introducing playful, exaggerated elements and complex spatial arrangements. Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), an architect, painter, and art historian, was instrumental in developing Mannerist architectural styles. His work at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence (begun 1560) introduced elongated windows, irregular proportions, and decorative details that deviated from classical norms.

One of the most unusual Mannerist architectural projects was the Palazzo del Te (1524–1534) in Mantua, designed by Giulio Romano (1499–1546). Unlike Renaissance buildings, which emphasized stability and harmony, the Palazzo del Te’s design included intentionally distorted columns, uneven facades, and illusionistic frescoes. This playful manipulation of classical elements was a hallmark of Mannerist architecture, signaling a move toward artificiality and intellectual sophistication.

5. The Role of Patrons and the Catholic Church in Mannerism

As with the Renaissance, wealthy patrons and religious institutions played a critical role in supporting Mannerist artists. However, by the mid-16th century, artistic commissions were increasingly tied to political power and religious propaganda, particularly in response to the Protestant Reformation (1517–1648).

In Italy, the Medici family remained one of the strongest patrons of Mannerist art. Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici (r. 1537–1574) actively commissioned works from Bronzino, Cellini, and Vasari to glorify his rule. The Medici court in Florence became a center for Mannerist portraiture, with artists portraying aristocratic subjects in highly refined, intellectual, and detached styles.

The Catholic Church, in response to the Protestant Reformation, embraced Mannerist art as part of its Counter-Reformation efforts. The Council of Trent (1545–1563) called for religious art that was clear, emotional, and spiritually engaging. This led to the rise of dramatic and expressive Mannerist religious paintings, particularly in Spain and Rome.

In Spain, King Philip II (r. 1556–1598) was a major patron of Mannerism, commissioning El Greco to create religious works that emphasized mysticism and divine intensity. One of the most important commissions was El Greco’s The Disrobing of Christ (1577–1579) for the Toledo Cathedral, a painting known for its elongated figures, heightened spiritual emotion, and bold colors.

In France, King Francis I (r. 1515–1547) invited Italian Mannerist artists to work on Fontainebleau Palace, creating the School of Fontainebleau (c. 1530–1580). Artists such as Rosso Fiorentino (1495–1540) and Primaticcio (1504–1570) introduced Mannerist elements into French court culture, emphasizing ornate decorations, allegorical imagery, and aristocratic elegance.

6. The Spread and Decline of Mannerism

Mannerism spread rapidly across Europe during the mid-to-late 16th century, influencing painting, sculpture, and architecture in Spain, France, England, and the Netherlands. However, by the early 17th century, Mannerism began to decline, giving way to the Baroque movement (c. 1600–1750).

In Spain, Mannerism thrived under El Greco, whose visionary, mystical style paved the way for Spanish Baroque painters like Diego Velázquez (1599–1660). His dramatic use of elongated figures, emotional intensity, and unnatural lighting influenced later religious art. However, after El Greco’s death in 1614, Spanish artists moved toward more naturalistic styles, marking the transition to the Baroque period.

In Italy, the death of Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici (r. 1574–1587) marked the decline of Florentine Mannerism, as new artistic trends emerged in Rome. Caravaggio (1571–1610), a pivotal Baroque artist, rejected Mannerist artificiality in favor of realism, dramatic lighting (tenebrism), and raw human emotion. His works, such as The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600), marked the end of the Mannerist aesthetic and the beginning of the Baroque age.

By 1620, Mannerism had largely faded from popularity, replaced by the grandeur, theatricality, and realism of Baroque art. However, its influence remained strong in decorative arts, court culture, and later artistic movements.

7. The Lasting Legacy of Mannerism

Despite its decline, Mannerism left a significant artistic legacy, influencing later movements in painting, sculpture, and architecture. Its emphasis on distortion, elegance, and intellectual complexity can be seen in various later artistic styles.

- Baroque art (1600–1750) borrowed Mannerism’s dramatic lighting and movement, seen in the works of Caravaggio and Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640).

- Rococo (1730s–1780s) continued the Mannerist fascination with elegance, decoration, and courtly refinement.

- 20th-century Surrealists, including Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), admired Mannerist elongation, dreamlike compositions, and psychological depth.

Today, Mannerist masterpieces remain highly valued, displayed in top museums such as the Uffizi Gallery, the Prado Museum, and the Louvre. Its intellectual, unconventional, and expressive approach to art continues to fascinate and inspire contemporary artists and scholars.

Key Takeaways

- Mannerism (1520–1600) was an artistic movement that emphasized elongation, exaggerated poses, and artificial elegance.

- It emerged in Italy after 1520, following Raphael’s death and the Sack of Rome (1527).

- Key artists included Pontormo, Parmigianino, Bronzino, and El Greco.

- It was supported by the Medici family, Catholic Church, and European courts.

- Mannerism’s influence extended into Baroque, Rococo, and modern art movements.