When one thinks of Paul Gauguin, images of vibrant Tahitian landscapes, rich with color and emotion, often come to mind. Among the many figures that populated these lush canvases, one stands out with particular significance: Teha’amana, Gauguin’s young Tahitian muse. Her presence in his life and work marks a profound chapter in the artist’s journey, reflecting both personal and cultural encounters that would shape the legacy of his art.

Before delving into Teha’amana’s impact on Gauguin, it’s essential to understand the context of his journey. By the late 1880s, Gauguin had grown disillusioned with European society and its artistic conventions. He yearned for a more authentic and unspoiled world, free from the constraints of Western civilization. This longing led him to Tahiti in 1891, where he hoped to find inspiration and a new way of life.

Gauguin’s initial arrival in Tahiti was filled with idealism. He envisioned the island as a paradise where he could escape the modern world’s complexities and immerse himself in a simpler, more “primitive” existence. This romanticized vision, however, soon met the realities of colonial influence and cultural change already affecting the island.

Tahiti, colonized by the French in the 19th century, was a place in flux. While Gauguin sought an untouched Eden, he found an island shaped by both indigenous traditions and the impositions of European colonialism. This duality profoundly influenced his work, as he navigated the tensions between his idealized perceptions and the lived realities of the Tahitian people.

Meeting Teha’amana

Teha’amana, often referred to by Gauguin as Tehura, was a young Tahitian girl, reportedly around 13 or 14 years old when they met. In the context of the time and culture, it was not unusual for young girls to enter into relationships with older men, especially foreigners. Gauguin and Teha’amana’s relationship, though controversial by today’s standards, was seen differently in their era and cultural milieu.

Teha’amana became a significant part of Gauguin’s life in Tahiti, both as a companion and a muse. She was central to his exploration of Tahitian culture and spirituality, often embodying the themes and imagery that would define his Tahitian works. Their relationship also provided Gauguin with a sense of belonging and connection to the island, despite his status as an outsider.

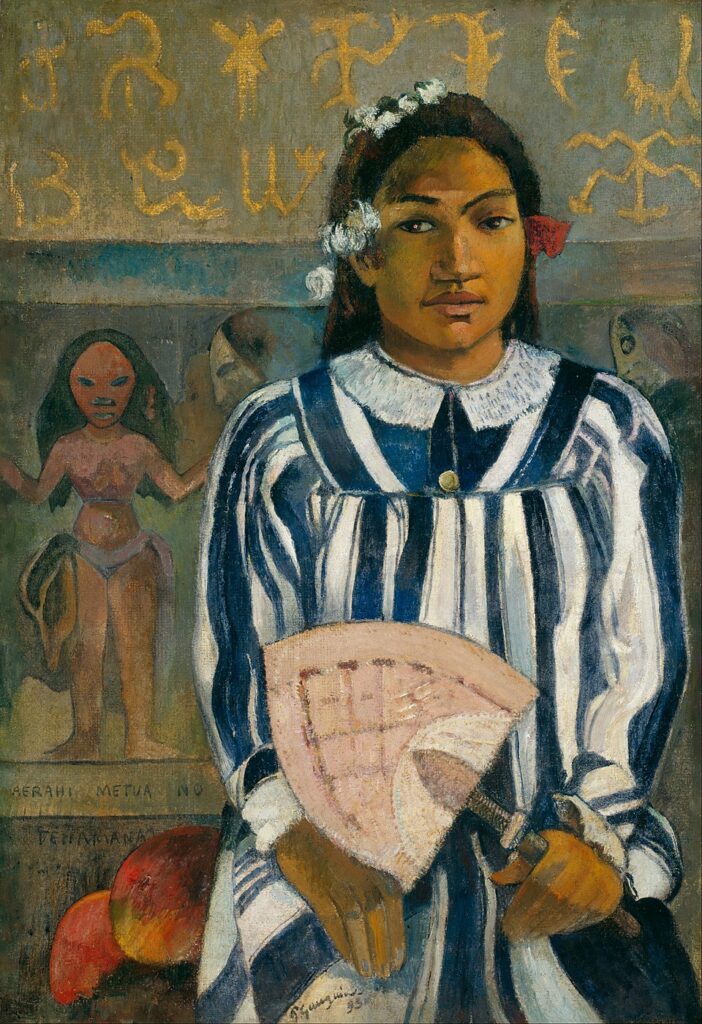

Teha’amana’s influence on Gauguin’s art is profound. She appears in several of his most famous works, her presence a muse-like figure that bridges his idealized visions of Tahiti with the reality of his experiences. Paintings such as “The Spirit of the Dead Watching” (1892) and “Tahitian Woman with a Flower” (1891) feature her prominently, reflecting Gauguin’s fascination with the local customs, myths, and everyday life.

In “The Spirit of the Dead Watching,” Teha’amana is depicted lying on her stomach, looking back with an expression that combines fear and curiosity. The painting is imbued with a sense of mystery and otherworldliness, capturing Gauguin’s interpretation of Tahitian spirituality and his own inner turmoil. The composition and emotional depth of the work illustrate how Teha’amana’s presence influenced not only the subject matter but also the mood and tone of Gauguin’s art.

“Tahitian Woman with a Flower” presents a more serene and idealized image of Teha’amana, embodying the exotic beauty and grace that Gauguin sought to capture in his depictions of Tahitian women. Her contemplative expression and the lush background highlight the natural harmony and tranquility that Gauguin associated with his Tahitian experience.

Teha’amana was more than just a model for Gauguin; she was a gateway to understanding Tahitian culture. Through her, Gauguin gained insights into local customs, myths, and daily life that he might not have otherwise accessed. This relationship allowed him to create works that, while still filtered through his own perspective and artistic vision, resonated with a deeper understanding of the culture he was depicting.

However, it’s important to recognize the complexity of this dynamic. Gauguin’s portrayal of Tahiti and its people, including Teha’amana, was influenced by his own preconceptions and the broader colonial context. His works often reflect a romanticized and exoticized vision of Tahiti, which can obscure the realities of the lives and cultures he encountered.

Gauguin’s letters and writings from this period reveal his fascination with the spiritual and mythical aspects of Tahitian culture. He often depicted Teha’amana in settings that evoke traditional Tahitian beliefs, blending these elements with his own artistic imagination. This fusion of reality and fantasy is a hallmark of Gauguin’s work, illustrating his quest to capture the essence of what he perceived as a more primal and authentic way of life.

Teha’amana’s Life Beyond Gauguin

While much is known about Teha’amana’s role in Gauguin’s life and work, her story beyond their relationship is less documented. After Gauguin left Tahiti to return to France and later moved to the Marquesas Islands, Teha’amana’s life continued in the community where she grew up. The details of her later years are sparse, but it is known that she married and had children, continuing her life in the changing landscape of colonial Tahiti.

Teha’amana’s life reflects the broader transformations occurring in Tahitian society during this period. The influence of European colonialism brought significant changes to the island’s social, cultural, and economic structures. Despite these upheavals, traditional customs and ways of life persisted, creating a complex and often contradictory environment in which Teha’amana and her contemporaries lived.

Gauguin’s relationship with Teha’amana, and his broader interactions with Tahitian culture, remain subjects of both admiration and controversy. His works from this period are celebrated for their innovative use of color and form, and their ability to convey deep emotional and spiritual themes. However, they also raise questions about the ethics of his relationships and the impact of his presence in a colonized land.

Modern perspectives often critique Gauguin’s relationships with young Tahitian women, viewing them through the lens of power dynamics and colonial exploitation. These critiques are essential in understanding the full scope of his legacy, acknowledging both the artistic achievements and the ethical complexities of his life and work.

Gauguin’s art from his Tahitian period is often seen as a pioneering exploration of non-Western subjects and aesthetics. His use of bold colors, simplified forms, and symbolic imagery had a profound influence on modern art, inspiring movements such as Fauvism and Primitivism. However, it’s crucial to contextualize these achievements within the realities of his interactions with the people and cultures he depicted.

Gauguin’s time in Tahiti marked a period of significant artistic innovation. Influenced by his immersion in Tahitian culture and his relationship with Teha’amana, he developed new techniques and approaches that distinguished his work from his contemporaries.

One of the most notable aspects of Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings is his use of color. He employed vibrant, unmodulated colors to create bold contrasts and evoke emotional responses. This approach was a departure from the more subdued and naturalistic color palettes of traditional European painting. Gauguin’s use of color was not just an aesthetic choice but a means of expressing the intense and often mystical experiences he associated with Tahitian life.

Gauguin also experimented with form and composition during this period. He often flattened perspective and used simplified, almost abstract shapes to convey his subjects. This approach allowed him to focus on the symbolic and emotional content of his paintings rather than mere representation. In works like “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” (1897), Gauguin combined these elements to create a complex narrative tableau that explores existential themes through the lens of Tahitian myth and symbolism.

Spirituality played a central role in Gauguin’s Tahitian works, and his relationship with Teha’amana was instrumental in deepening his understanding of local beliefs and practices. Tahitian spirituality, characterized by a rich tapestry of myths, gods, and rituals, fascinated Gauguin and provided a wealth of material for his artistic exploration.

Gauguin was particularly drawn to the concept of mana, a spiritual force believed to inhabit all things in Polynesian cultures. This idea resonated with his own beliefs about the interconnectedness of life and the mystical qualities of art. He sought to imbue his paintings with a sense of mana, creating images that were not just visually striking but also spiritually potent.

In paintings like “The Spirit of the Dead Watching,” Gauguin incorporated elements of Tahitian mythology and spirituality to create a sense of otherworldly presence. The use of dark, luminous colors and eerie, dreamlike compositions reflects his attempt to capture the mystical atmosphere he associated with Tahitian spiritual beliefs.

The Broader Impact of Gauguin’s Tahitian Period

Gauguin’s time in Tahiti had a lasting impact on the art world, influencing not only his own work but also that of subsequent generations of artists. His bold use of color, innovative compositions, and incorporation of non-Western themes challenged conventional notions of art and opened new possibilities for creative expression.

Artists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso were inspired by Gauguin’s work, particularly his Tahitian paintings. Matisse’s exploration of color and form in his Fauvist works can be seen as a direct continuation of Gauguin’s experiments. Picasso’s interest in Primitivism and his incorporation of African and Oceanic influences into his Cubist works also owe a debt to Gauguin’s pioneering approach.

Gauguin’s influence extended beyond painting to other art forms as well. His ideas about the spiritual and symbolic potential of art resonated with writers, musicians, and filmmakers, contributing to a broader cultural movement that sought to break free from the constraints of traditional Western aesthetics and explore new modes of expression.

Today, the story of Paul Gauguin and Teha’amana serves as a complex and multifaceted lens through which to view the intersections of art, culture, and history. Their relationship, while emblematic of Gauguin’s artistic journey, also highlights the ethical and cultural challenges inherent in such encounters.

Gauguin’s portrayal of Teha’amana and other Tahitian subjects continues to be scrutinized and re-evaluated in light of contemporary understandings of colonialism and cultural appropriation. This critical perspective is essential for a nuanced appreciation of his work, acknowledging both its artistic significance and the problematic aspects of its creation.

At the same time, Teha’amana’s presence in Gauguin’s art invites us to consider the agency and resilience of the individuals who became part of his artistic narrative. Her image, immortalized in Gauguin’s paintings, speaks to the enduring power of art to capture and convey the complexities of human experience.

Teha’amana’s influence on Paul Gauguin’s art is undeniable. She played a crucial role in his Tahitian period, inspiring some of his most famous and evocative works. Her presence in his life opened doors to deeper cultural understanding and artistic exploration, even as it highlighted the complexities and contradictions of Gauguin’s pursuit of an idealized paradise.

As we look at Gauguin’s art today, it’s important to appreciate the beauty and innovation of his work while also recognizing the human stories and cultural dynamics that shaped it. Teha’amana, as his young Tahitian muse, is a poignant reminder of the intricate interplay between artist and subject, culture and creativity, and the enduring impact of these encounters on the world of art.