Throughout history, religious art and sacred treasures have played a vital role in shaping national identity and cultural continuity—especially in Poland. Warsaw, the spiritual heart of the country, once housed an extraordinary array of gold and silver liturgical objects crafted over centuries. These artifacts were not merely decorative; they were expressions of deep Catholic devotion and artistic achievement. However, much of this ecclesiastical wealth vanished after World War II, not during the fighting itself, but during the Soviet occupation that followed.

Between 1945 and the early 1950s, churches across Warsaw reported the disappearance of valuable relics, chalices, tabernacles, monstrances, and reliquaries—many of which dated back to the 17th and 18th centuries. Though little discussed in postwar Soviet narratives, these seizures were systematic. The Red Army and NKVD (Soviet secret police) stripped Poland’s religious institutions of their treasures under the guise of “protection,” funneling much of the loot eastward. Today, the fate of these objects remains a mystery. Some are thought to reside in Russian museums or vaults; others were likely melted down, destroyed, or sold into private collections. The loss is not only financial or artistic—but deeply spiritual.

The Splendor of Warsaw’s Sacred Treasures

A Glimpse into Poland’s Liturgical Art

Poland’s Catholic tradition has always placed a strong emphasis on beauty in worship. From the medieval period onward, churches across the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth commissioned intricate liturgical objects fashioned from gold, silver, enamel, and gemstones. These were used in Mass, processions, and sacred rites. By the 16th century, Warsaw had become a central hub for this sacred craftsmanship, drawing silversmiths and goldsmiths from as far as Augsburg, Rome, and Prague.

Liturgical treasures such as golden monstrances—used to display the Eucharist—silver chalices, and richly adorned reliquaries were common in Warsaw’s major churches. Each object carried theological symbolism as well as national pride. Chalices bore the coats of arms of noble Polish families; reliquaries often held relics of saints with local or royal significance. Many of these items were passed down through generations, gifted by kings, bishops, or wealthy citizens in acts of piety and public devotion.

Notable Churches and Their Masterpieces

Among the churches most famous for their liturgical treasures was the Archcathedral Basilica of St. John the Baptist, located in Warsaw’s Old Town. Rebuilt multiple times since its original 14th-century construction, it housed a Baroque tabernacle made entirely of gilded silver and adorned with semi-precious stones. A golden monstrance commissioned by King Sigismund III Vasa in the early 1600s was also recorded in the church’s inventories prior to 1939.

The Church of the Holy Cross on Krakowskie Przedmieście Street, consecrated in 1696, held relics of the True Cross and a large silver reliquary shaped like a cross, believed to be a gift from Queen Marie Casimire. Its treasury also contained a golden chalice encrusted with rubies and sapphires, which had been in use since at least the 18th century. The Capuchin Church, established in the 1680s, was well known for its silver altarpieces and baroque tabernacles. Many of its objects were looted or removed during the Soviet period and have never reappeared.

Artistic Styles and Influences

Warsaw’s liturgical objects reflected a blend of European artistic styles with a distinctly Polish religious ethos. The Baroque period—roughly 1600 to 1750—was especially influential, marked by dramatic ornamentation and spiritual intensity. Goldsmiths trained in Italy and Southern Germany contributed to the elaboration of tabernacles and monstrances that featured sunbursts, angels, and inscriptions in Latin and Old Polish.

Gothic influences were still visible in older chalices and reliquaries preserved in Warsaw’s churches. These objects often featured finely wrought filigree work and enamel depictions of saints. The Polish wing of the Counter-Reformation heavily patronized religious art, favoring grand displays of devotion through materials like gold and silver. Local artisans mixed European design traditions with Polish heraldry and iconography, making many of these artifacts culturally unique and virtually impossible to replace.

Top 5 Known Lost Artifacts Before WWII:

- Golden monstrance from St. John’s Basilica (17th century)

- Reliquary cross from the Church of the Holy Cross (c. 1700)

- Gilded tabernacle from Capuchin Church (18th century)

- Ruby-studded chalice from St. Anne’s Church (early 1800s)

- Bishop’s pastoral staff made of chased silver (unknown origin)

Soviet Seizures and Destruction After 1945

Red Army Entry into Warsaw

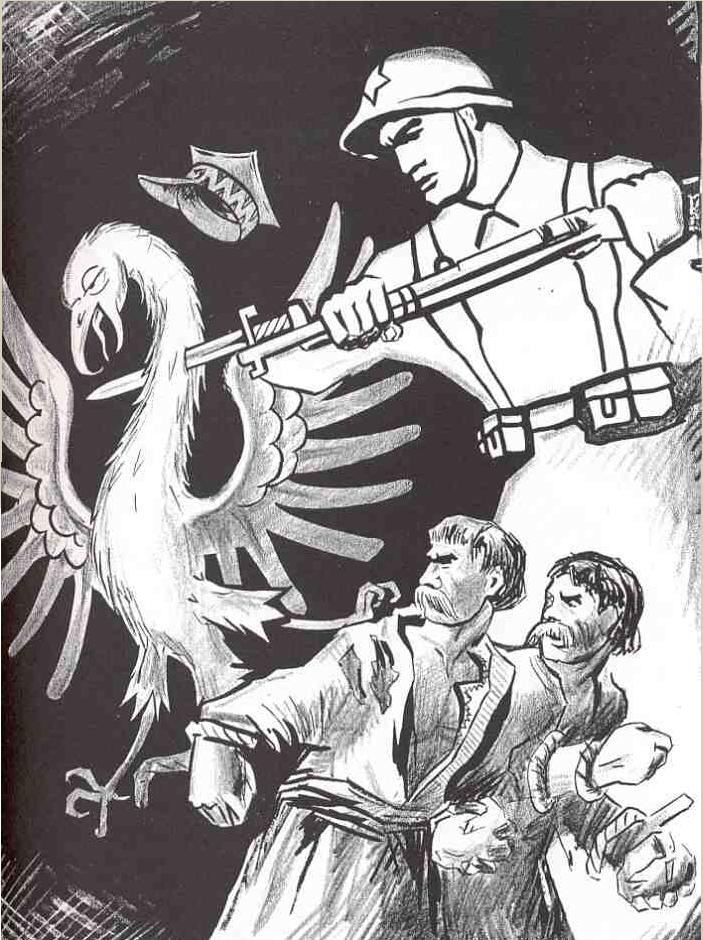

The Red Army entered the ruins of Warsaw in January 1945 after the city had been razed by German forces during the failed Warsaw Uprising of August–October 1944. What remained of the Old Town was a pile of rubble, but many churches, although damaged, still housed relics, artworks, and sacred vessels hidden in crypts or sacristies. Soviet forces were initially welcomed as liberators from German occupation. However, that sentiment quickly changed.

Unlike the Germans, who had systematically catalogued and removed valuable items during the occupation, the Soviet approach was more opaque and often brutal. The NKVD and Red Army units quickly moved to “secure” what remained in religious buildings. In many cases, priests and monks were evicted or arrested, and church vaults were opened under military guard. Inventories of valuable items were seized, and within months, truckloads of gold, silver, and jeweled religious items began disappearing eastward, ostensibly for “safe-keeping.”

Systematic Removal of Church Valuables

Archival records and church testimonies indicate that the looting was organized and thorough. Teams of Soviet officers, often accompanied by Polish communist collaborators, combed through the wreckage of major churches looking for anything of value. Gold and silver were prime targets—not for artistic preservation, but for economic gain. Items were wrapped, crated, and transported either by rail or military convoy.

The removal of church property was framed by Soviet authorities as a necessary step in securing national assets from future conflict. However, there was no record of these items being returned. What began as emergency protection quickly became a one-way extraction. Churches were left empty, and Poland’s postwar communist government—subservient to Moscow—did little to resist. There are documented instances where priests attempting to hide sacred objects were imprisoned or disappeared.

Documented Cases of Confiscated Treasures

While Soviet records on the matter remain largely sealed or inaccessible, there are surviving Polish church inventories from 1944–1945 that list items present before Soviet occupation—and conspicuously missing afterward. The Cathedral Basilica’s last inventory under Canon Władysław Zientarski (dated March 1945) includes a golden monstrance, six silver candelabra, and a reliquary chest, all of which vanished later that year.

In another case, Father Stanisław Grabski of the Holy Cross Church recorded the removal of a gilded chalice and four silver processional crosses by uniformed Soviet soldiers in April 1945. Oral testimony from surviving clergy and parishioners from the Church of the Visitation describes the forced opening of the sacristy safe by NKVD officers and the loading of three large chests into Soviet trucks. None of the objects from these seizures have been recovered or identified in public collections.

The Fate of the Missing Gold and Silver

Theories and Evidence on Treasure Dispersal

After the Soviet seizures, the trail of Poland’s church treasures goes dark. Some scholars and cultural officials believe that many of the items were transported to the Soviet Union and absorbed into state museum holdings—either in Moscow, Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), or regional institutions across Belarus and Ukraine. However, because Soviet archives remain largely inaccessible or redacted, concrete evidence has been difficult to obtain.

Another theory is that much of the silver and gold was simply melted down for its material value. In the chaotic postwar years, the USSR was hungry for precious metals to support reconstruction, industry, and state-controlled banking. Ornate chalices and reliquaries may have been destroyed for bullion. Black market operations were also a possibility. Some Polish church objects have surfaced over the decades in private auctions and collections, though few could be definitively linked to specific Warsaw parishes due to the loss of detailed pre-war documentation.

International Recovery Efforts

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Polish government began to pursue limited cultural repatriation. However, the focus remained largely on paintings and manuscripts, not liturgical metalwork. Diplomatic efforts to locate and return stolen church treasures have faced significant barriers, including Russian refusal to acknowledge wartime and postwar looting by Soviet forces.

In 2004, the Polish Ministry of Culture submitted formal requests for inventory checks of Russian museums suspected of holding Polish artifacts. These were largely ignored or denied. Efforts by the Catholic Church in Poland, as well as appeals made through the Vatican and the European Union, have had minimal impact. Without bilateral restitution treaties or public acknowledgment from Russian institutions, the possibility of recovering these treasures remains slim.

Known Recoveries and Ongoing Mysteries

Despite the challenges, there have been isolated successes. In the early 2000s, an 18th-century Polish chalice believed to have originated from a Warsaw church surfaced at an antique dealer in Munich. With the cooperation of German authorities, it was returned to Poland in 2003 and is now held by the Archdiocese of Warsaw. However, it remains an exception rather than a rule.

Other items—some clearly marked with Polish ecclesiastical seals—have appeared in private collections in France, Austria, and even the United States. Unfortunately, the burden of proof for reclaiming these objects is high, and many parishes no longer have the surviving documentation to make a legal case. Among the most infamous missing items are the golden tabernacle of St. Anne’s Church, a jeweled reliquary shaped like a dove, and an ornate processional cross known to have been used by Cardinal Aleksander Kakowski before his death in 1938.

5 Famous Artifacts Still Missing:

- Golden tabernacle from St. Anne’s Church (last seen 1944)

- 17th-century reliquary shaped like a dove (St. Martin’s Church)

- Processional cross of Cardinal Kakowski (recorded 1936)

- Bejeweled monstrance from Capuchin Church treasury

- 18th-century chalice with Polish royal arms (Holy Cross Church)

Cultural and Religious Impact on Poland Today

Spiritual Loss and National Memory

The loss of Warsaw’s sacred treasures was not merely a cultural or material setback—it was a deep spiritual wound for the Polish nation. For centuries, these objects played a central role in the life of the Church and the faithful. Their disappearance left altars bare and broke a chain of continuity that had survived wars, partitions, and occupations. The sacred vessels and reliquaries were not just tools of worship; they were part of Poland’s religious identity.

Polish Catholics have always had a strong connection to their religious symbols, especially in the face of foreign domination. Losing these treasures to a hostile atheistic regime was more than theft—it was sacrilege. To this day, many churches maintain plaques or small exhibitions listing the items lost or stolen in the postwar years. These memorials serve as both historical records and spiritual laments for what was taken.

Political Silence and Historical Revision

During the communist era (1945–1989), discussion of Soviet looting was strictly forbidden in Poland. The regime, under pressure from Moscow, promoted a version of history that painted the Soviets solely as liberators. The devastation they caused—including the removal of religious artifacts—was suppressed in state media, schools, and official publications. Church officials who spoke openly about the thefts risked harassment, arrest, or worse.

This silence delayed national and international awareness of the scale of the cultural losses. Only after the fall of communism did historians and archivists begin to uncover the extent of the plunder. However, even today, the topic receives little attention in Western media or academic circles, which often focus more on Western European restitution cases. Poland’s appeals are still met with political hesitancy or outright dismissal by Russian authorities.

Preservation and Education in Modern Poland

Despite the losses, Poland has made a strong effort to preserve what remains of its religious art. Museums such as the Archdiocesan Museum in Warsaw and the Royal Castle Museum now hold what few treasures survived the war and occupation. Many pieces were recovered from hidden caches in crypts, buried in convent gardens, or smuggled abroad by clergy during the 1940s. Today, these institutions work closely with the Church to catalog and protect them.

Polish schools have also begun including material on cultural losses under Soviet occupation. Students learn not only about the physical destruction of churches but also about the symbolic theft of religious identity. Exhibitions such as “Sacrum Spoliatum: The Lost Treasures of Polish Churches,” held in Warsaw in 2019, have helped raise awareness domestically and internationally. Still, many believe that only full restitution—if it ever comes—can begin to heal the wound inflicted by the postwar looting.

Key Takeaways

- After 1945, Soviet forces seized vast quantities of gold and silver religious artifacts from Warsaw’s churches, many of which were centuries old.

- Sacred objects like monstrances, chalices, and reliquaries vanished during the Soviet occupation under the pretext of “securing” national assets.

- Few items have ever been recovered; many are believed to have been destroyed, melted down, or hidden in Russian museum collections.

- Poland’s communist regime suppressed any discussion of these thefts, leaving a deep historical and spiritual silence for decades.

- Modern Polish institutions are working to document, preserve, and educate the public about this cultural and religious loss.

Frequently Asked Questions

What happened to the church treasures of Warsaw after World War II?

They were systematically removed by Soviet forces starting in 1945 and transported east. Most were never returned or accounted for.

Were the artifacts taken during wartime or afterward?

Most seizures occurred after the war, during the Soviet occupation of Poland, not during active fighting.

Has Poland recovered any of these lost treasures?

Only a handful of items have been recovered, mostly from antique dealers or private collections abroad.

Why doesn’t Russia return the stolen church objects?

Russia has not acknowledged responsibility and offers no access to archives or museum inventories related to Polish church items.

Are there efforts today to find these missing artifacts?

Yes, but they are hindered by political obstacles, lack of documentation, and uncooperative institutions in Russia and Belarus.