For more than a thousand years, Kyoto has been the sacred wellspring of Japanese art and aesthetics. Nestled in a valley encircled by forested mountains, this ancient city—formerly known as Heian-kyō—was established in 794 as Japan’s imperial capital. That status endured for over a millennium, and with it came an unparalleled concentration of artistic, religious, and cultural development. To speak of Kyoto’s art history is not merely to discuss styles and techniques but to enter into a dialogue with Japan’s evolving self-conception—through brushstrokes, gardens, temples, fabrics, and forms of daily grace.

Kyoto’s emergence as a cultural center was not incidental. When Emperor Kanmu moved the court to Heian-kyō, he did so in part to escape the growing influence of Buddhist institutions in Nara. But ironically, Kyoto would become one of the greatest centers for Buddhist art in the world. The city’s structured layout, inspired by Chinese Tang dynasty capitals, fostered a sense of order and ritual that would influence the arts profoundly. From the start, Kyoto was designed to express cosmic harmony and imperial authority—a fusion of spiritual vision and political symbolism.

The city quickly attracted poets, calligraphers, artisans, and architects who found patronage in the imperial court and the aristocratic class. Art in Kyoto was never a mere luxury; it was deeply entwined with philosophy, religion, and social identity. The Heian elite, particularly the court women, cultivated a refined sensibility expressed in diaries, poetry, and the delicate Yamato-e paintings that illustrated these works. Over time, this sensitivity to nuance, texture, and mood would shape the DNA of Japanese aesthetics.

As different political powers rose and fell—the Kamakura shogunate, the Ashikaga, the Toyotomi, the Tokugawa—Kyoto retained its gravitational pull. Though the political center eventually shifted to Edo (modern-day Tokyo), Kyoto remained the soul of the nation. Even during times of war and decline, artists in Kyoto continued to develop and preserve techniques in painting, ceramics, metalwork, lacquer, and textiles. Temples rebuilt after fires often retained their original artistic intentions, demonstrating a remarkable reverence for continuity.

Kyoto’s geography played an understated but essential role. Unlike Edo, which was built up rapidly for practical governance, Kyoto was shaped slowly, spiritually, and with attention to the environment. The mountains and rivers that frame the city became motifs in art, while also influencing the physical layouts of temples and gardens. Kyoto’s famous fogs and seasonal transitions—cherry blossoms in spring, crimson maples in autumn—offered endless inspiration for painters and poets alike.

Another defining trait of Kyoto’s art history is its dialog between the ephemeral and the eternal. In a city prone to fires, invasions, and periodic destruction, a deep philosophy took root: beauty must accommodate impermanence. This attitude would later crystallize into aesthetic ideals like wabi-sabi, which embrace simplicity, asymmetry, and the melancholy beauty of decay. Kyoto, more than any other city, became the canvas for this philosophical view of life and art.

Today, despite the modern world encroaching on all sides, Kyoto’s artistic legacy endures not as a static museum of the past but as a living, evolving tradition. Walk through the Gion district and you may glimpse a geisha, her kimono crafted with centuries-old textile techniques. Visit a tea house and you’ll encounter ceramic bowls fired in kilns that have been active since the 16th century. Step into one of its many art museums, and you might see a contemporary installation that converses subtly with the Zen gardens of old.

Kyoto is not just the former capital of Japan. It is the capital of a sensibility—an aesthetic worldview that has shaped everything from architecture and painting to cuisine and fashion. To understand the art history of Kyoto is to understand the essence of Japanese art itself: refined, resilient, quietly radical.

Heian Period (794–1185): The Birth of Classical Japanese Aesthetics

The Heian period marks the dawn of Japan’s classical cultural identity, and nowhere was this more powerfully realized than in Kyoto—then called Heian-kyō, “Capital of Peace and Tranquility.” This era witnessed the transformation of Japanese art from its continental roots in Chinese Tang aesthetics to a native, refined visual language that celebrated subtlety, courtly grace, and emotional nuance. Kyoto, as the imperial seat, became the crucible for this transformation, giving birth to forms of artistic expression that still define the soul of Japanese aesthetics today.

At the heart of this cultural flowering was the aristocratic court centered around the emperor. Though nominally powerful, the emperor’s political authority was often overshadowed by powerful families, particularly the Fujiwara clan. Yet it was precisely within this rarefied and sheltered world that the arts thrived. Courtly life in Kyoto emphasized miyabi—elegance and refinement—as both an aesthetic ideal and a social necessity. The arts were not ornamental but essential tools for communication, seduction, and spiritual contemplation.

One of the most important developments of the period was the emergence of Yamato-e, the first truly Japanese style of painting. In contrast to the earlier kara-e (Chinese-style painting), Yamato-e turned its gaze inward, depicting native landscapes, seasons, and literature with an eye toward emotional resonance rather than doctrinal precision. These paintings typically employed soft colors, flowing lines, and an emphasis on atmosphere, often capturing poetic scenes from classical texts or courtly life.

The emaki—painted handscrolls—became a dominant form, allowing narrative to unfold gradually as the viewer unrolled the scroll. These scrolls were more than illustrations; they were immersive experiences that fused visual, literary, and emotional elements. Perhaps the most celebrated example is the Genji Monogatari Emaki, an early 12th-century pictorial adaptation of The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu. This work, considered the world’s first novel, was written by a court lady and is itself a masterpiece of Heian literature. The emaki captures the fragile emotions and courtly decorum of the story through delicate facial expressions, “blown-off roof” perspectives (allowing viewers to peer into interior spaces), and evocative color gradations.

Women were key figures in the cultural life of the Heian court. Denied formal political power, they turned to literature, poetry, and painting as means of expression and influence. In addition to Murasaki Shikibu, figures like Sei Shōnagon—author of The Pillow Book—brought a sharp, observational eye to daily life. The writings of these women weren’t just literary landmarks; they influenced visual artists who sought to capture the mood, rhythm, and aesthetics described in their prose. In this way, Kyoto’s art history is deeply interwoven with the legacy of female authorship and sensibility.

Religious art also flourished, particularly in the realms of esoteric Buddhism (mikkyō), which had been imported from China in the early 9th century. The temples of Kyoto—such as Tō-ji and Daigo-ji—became centers for the production of mandalas, ritual sculptures, and ceremonial implements. These works were often opulent and symmetrical, emphasizing cosmic order and spiritual elevation. The Shingon and Tendai sects, which thrived during this period, commissioned gilded bronze statues and elaborate iconography that merged Chinese visual logic with Japanese materials and craftsmanship.

Yet even as religious art emphasized transcendence, secular court art turned toward impermanence and introspection. The concept of mono no aware—the gentle sadness or sensitivity to the ephemerality of things—gained ground during the Heian period, particularly in poetry and painting. Cherry blossoms became a favored motif not only for their beauty but for their fleeting bloom. Kyoto’s seasonal rhythms, still celebrated in festivals today, were already deeply embedded in Heian visual culture.

Architecture, too, began to express a new aesthetic during this era. The shinden-zukuri style of palace architecture reflected the ideals of openness, harmony with nature, and graceful living. Residences were laid out in a U-shape with open verandas, gardens, and reflecting pools, inviting a constant interplay between interior and exterior spaces. This architectural style was echoed in the layouts of Buddhist temples and, centuries later, would influence the structure of tea houses and Zen gardens.

By the late Heian period, the seeds of what we now think of as “Japanese art” had been fully planted. The shift from imported Chinese modes to native forms wasn’t total—Chinese influence remained strong in Buddhist art and calligraphy—but the direction was clear. Kyoto had become the birthplace of a national aesthetic, one rooted in quietude, suggestion, and the power of nature. The emphasis on atmosphere over realism, emotion over doctrine, and impermanence over permanence would endure through the centuries.

The Heian period established Kyoto not merely as a political capital but as the spiritual and cultural wellspring of Japan. Its court painters, poets, and architects did not just create beautiful things—they articulated a worldview. In their hands, art became a mirror for human experience, a medium for spiritual longing, and a language of subtle emotions. That mirror still reflects back at us today, in the way Japanese art continues to blend restraint with radiance, and form with feeling.

Religious Art and Temple Culture

To walk the streets of Kyoto is to walk through a sacred archive. With over 1,600 temples and 400 shrines, the city is a living museum of religious art and architecture, its skyline shaped as much by tiled temple eaves and pagodas as by mountains and clouds. From the austere minimalism of Zen rock gardens to the opulent interiors of Shingon sanctuaries, Kyoto’s religious art offers not only a window into Japan’s spiritual evolution but also into the material and visual culture that shaped, and was shaped by, the divine.

The roots of Kyoto’s religious art trace back to the city’s founding in 794, when Emperor Kanmu moved the capital from Nara. While part of the motivation was to escape the growing political entanglement of Buddhist institutions, the influence of Buddhism on Kyoto’s art was immediate and profound. Early temples such as Tō-ji and Sai-ji, constructed on either side of the imperial avenue, were envisioned as protective sentinels of the capital and soon became centers of sacred art production.

One of the defining features of religious art in Kyoto is its deep connection to Esoteric Buddhism—particularly the Shingon and Tendai sects introduced from China in the early 9th century by monks like Kūkai and Saichō. These sects emphasized mystical rites, elaborate rituals, and a complex cosmology that required a vast visual language to express. The result was a flowering of sacred imagery: mandalas teeming with deities, cosmic diagrams of the universe, and intricate iconography that merged symbolism with stunning craftsmanship.

The mandala, in particular, became a central artistic form. These symmetrical paintings, such as the Womb World Mandala (Taizōkai) and Diamond World Mandala (Kongōkai), were more than decorative—they were tools for visualization and meditation, mapping the metaphysical universe. The production of these mandalas in Kyoto’s temple ateliers combined spiritual devotion with technical brilliance, incorporating natural pigments, gold leaf, and silk.

Religious sculpture also thrived. Artisans created lifelike statues of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and guardian deities from wood, bronze, and gilded lacquer. Some of the finest surviving examples—such as the thousand-armed Kannon at Sanjūsangen-dō or the fierce guardians at Ninna-ji—were not only devotional objects but also reflections of the extraordinary skill and spiritual discipline of Kyoto’s sculptors. These statues were often installed in darkened halls, illuminated only by lantern light, producing an immersive, reverential atmosphere that remains effective to this day.

Kyoto’s religious art evolved in dialogue with architecture. The temples themselves were conceived as mandalas in space—spiritual maps built into wood, stone, and garden. The Heian-era temples embraced symmetry and grandeur, with wide eaves and columned halls. Later, the influence of Zen Buddhism, arriving in the Kamakura period, shifted the architectural vocabulary toward simplicity and restraint. Structures like the abbot’s quarters at Ryōan-ji or the understated gates at Daitoku-ji embodied the Zen principles of emptiness and non-attachment.

Gardens became an essential component of religious expression. Initially designed as representations of the Pure Land—paradises filled with lotus ponds and symbolic bridges—temple gardens evolved into more abstract compositions. The karesansui (dry landscape) gardens associated with Zen monasteries like Ryōan-ji used raked gravel, carefully placed rocks, and moss to evoke landscapes and invite meditation. These gardens were not mere ornaments but visual koans—puzzles in stone meant to sharpen the mind and dissolve ego.

Painting within temple culture also underwent transformation. Sumi-e (ink painting), introduced from China, was adapted by monk-artists like Sesshū Tōyō and Josetsu into a uniquely Japanese form. These monochrome landscapes, with their washes of gray and black, captured the spiritual tension between form and void. They aligned with the Zen aesthetic of minimalism and impermanence, and their compositional asymmetry mirrored the unpredictability of life itself.

Beyond the walls of temples, Kyoto’s religious festivals and rituals contributed to the city’s visual richness. Ceremonial garments, ritual implements, and portable shrines were all crafted with exquisite attention to detail. The annual Gion Matsuri, originally a purification ritual to ward off plague, evolved into one of the most visually spectacular events in Japan, featuring processions of elaborately decorated floats designed and painted by local artisans.

Importantly, the creation and maintenance of religious art in Kyoto fostered an entire ecosystem of specialized craftspeople: carpenters, metalworkers, lacquer artists, calligraphers, and textile dyers. Many of these guilds were centered in Kyoto and passed down techniques across generations. This continuity explains how certain temples still contain original artworks or faithful restorations based on centuries-old methods.

Kyoto’s temple culture also served as a refuge during times of war. When Kyoto faced destruction—especially during the Ōnin War (1467–1477)—temples became repositories of cultural memory. Monks, scholars, and artisans worked to preserve not only the religious texts but also the paintings, sculptures, and architectural blueprints that could one day help reconstruct a fallen world.

In sum, religious art in Kyoto is not a separate stream from its broader art history—it is the main artery. From grand halls that house cosmic visions to the meditative rock gardens that invite silence, the sacred arts of Kyoto shaped the city’s identity and aesthetic ethos. They continue to do so today, not only as historical artifacts but as living traditions—encountered daily by pilgrims, tourists, and residents alike who are invited to step into centuries of devotion, discipline, and transcendental beauty.

Kamakura and Muromachi Periods: Zen and the Warrior Aesthetic

With the fall of the Heian aristocracy and the rise of the warrior class in the late 12th century, Japan entered a new era—one marked by austerity, realism, and a shift in the spiritual and aesthetic currents of the nation. Kyoto, no longer the center of political power, remained the heart of cultural life, and it was here that a profound transformation took place. The Kamakura (1185–1333) and Muromachi (1336–1573) periods saw the rise of Zen Buddhism, which would dramatically reshape Japanese art. This shift brought a new aesthetic centered on simplicity, discipline, and the spiritual clarity of empty space—an ideal that would leave a lasting imprint not only on painting and sculpture, but also on architecture, garden design, and even everyday objects.

While the Kamakura period is often associated with realism and the physicality of warrior culture, it also witnessed the growing influence of Zen, particularly through contacts with the Chinese Song dynasty. Zen emphasized meditation and direct experience over scripture or ritual, and it demanded a new visual language: one that could evoke the ineffable with a few brushstrokes or the placement of a stone. Kyoto, with its ancient temples and entrenched artisan communities, became a fertile ground for this artistic revolution.

Perhaps no figure embodies the Zen aesthetic more than Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506), a Zen monk-painter trained in Kyoto who would go on to master sumi-e, the art of ink wash painting. Influenced by Chinese literati traditions, Sesshū’s paintings—especially his landscapes—use minimal brushwork to express profound depth and emotion. In compositions such as Winter Landscape, he uses gradations of ink and carefully controlled voids to render mountain peaks lost in mist, capturing the transience of nature and the stillness of meditation. Sesshū’s work, though created in the late Muromachi period, stands as a culmination of Zen’s artistic philosophy.

But the story of Kyoto’s Zen art cannot be told through painting alone. One of the most significant contributions of this period was in architecture and garden design, particularly through the development of Zen temples like Ryōan-ji, Daitoku-ji, and Myōshin-ji. These complexes were built not as grand religious monuments but as places of training and meditation. Their halls, tea rooms, and gardens were marked by unadorned wood, tatami mat interiors, and a deliberate avoidance of ornamentation. Every element, from the curve of a roof beam to the grain of a pillar, was meant to encourage clarity of mind and stillness of heart.

The karesansui, or dry landscape garden, became a hallmark of the Zen temple complex. At Ryōan-ji, a rectangle of white gravel punctuated by 15 moss-covered rocks arranged in enigmatic clusters invites quiet contemplation. The meaning is left undefined, and therein lies the point: the viewer brings their own experience to the composition, just as a Zen practitioner must wrestle with a kōan in meditation. These gardens are not merely “art” in the Western sense—they are spiritual tools, lessons in discipline, impermanence, and restraint.

Sculpture during this period retained its religious function but was transformed by realism. The Kamakura school of sculpture, with masters like Unkei and Kaikei, produced powerful statues of Buddhist deities and warrior guardians that seem to breathe and pulse with inner life. Unlike the graceful, almost ethereal figures of the Heian era, these statues were carved with deep emotion, muscular tension, and expressive faces. They reflect the new audience for religious art: the warrior class, whose world was one of impermanence, battle, and spiritual urgency.

At the same time, Kyoto was home to elite warrior families and shoguns who became significant patrons of the arts. During the Muromachi period, the Ashikaga shogunate, headquartered in Kyoto, played a pivotal role in developing what we now think of as classical Japanese aesthetics. Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu sponsored the construction of the Kinkaku-ji (Golden Pavilion), blending Zen simplicity with aristocratic opulence. His grandson, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, built the Ginkaku-ji (Silver Pavilion) and surrounded himself with artists, poets, and tea masters. This circle—sometimes called the Higashiyama culture—cultivated the wabi-sabi ideal: a love of the rustic, the weathered, the imperfect.

The tea ceremony (chanoyu), which would fully bloom in the next century under Sen no Rikyū, began to take shape in Muromachi Kyoto, as did the architectural form of the shoin-zukuri, the formal reception room that evolved into the core of Japanese domestic space. Screen paintings by the Kano school, whose Kyoto-based workshops would dominate for centuries, became prominent during this time, combining Chinese-inspired brushwork with large-scale compositions suited for the interiors of temples and elite residences.

Even as the country faced internal conflict and eventual descent into the Sengoku (Warring States) period, Kyoto remained a city of cultural continuity. Temples were destroyed and rebuilt; art studios moved or closed, yet the philosophical underpinnings of Zen art—simplicity, impermanence, and inwardness—continued to shape the city’s artistic consciousness.

In many ways, the Kamakura and Muromachi periods laid the groundwork for the Japanese aesthetic identity: a world of ink paintings, silent gardens, rough-hewn teahouses, and weathered sculptures. They shifted the focus from heavenly deities to the here and now—from transcendent ideals to the raw material of life itself. Through Zen, Kyoto’s art became quieter, more introspective, but no less profound. It is a silence that still resonates today in every gravel ripple, every brushstroke of ink, and every breath drawn within a temple gate.

The Golden Pavilion and the Aesthetic of Impermanence

Few structures in the world embody the paradox of impermanence and enduring beauty as profoundly as Kyoto’s Kinkaku-ji, the Golden Pavilion. Rising beside a still pond, its gilded exterior gleaming against pine trees and reflected in glassy water, Kinkaku-ji has become one of the most iconic images of Japan. But beyond its shimmering façade lies a story not only of artistic innovation, but of philosophical depth—rooted in the concept of mujo, or impermanence, which defines so much of Japanese aesthetics.

Originally built in the late 14th century as a retirement villa for Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third shogun of the Muromachi shogunate, the structure was officially known as Rokuon-ji, named after Yoshimitsu’s posthumous Buddhist title. After his death, the villa was converted into a Zen temple. The choice was symbolic: the intersection of political power, wealth, spiritual aspiration, and aesthetic contemplation converged in this single site. Yoshimitsu was a patron of arts, an admirer of Chinese Song dynasty culture, and a ruler with grand ambitions—Kinkaku-ji was his personal statement, and by extension, a statement about the artistic direction of Kyoto.

Kinkaku-ji’s design is a study in contrast and harmony. The three-tiered pavilion reflects three different architectural styles. The first floor, Shinden-zukuri, mirrors the aristocratic palaces of the Heian period, with open verandas and natural wood. The second floor adopts the Buke-zukuri style of the samurai, more closed and defensive. The third floor, a golden chamber sheathed in lacquer and gold leaf, is built in the Karayo (Zen temple) style, topped by a phoenix finial. Together, these levels create a vertical narrative of Japan’s cultural evolution, and of the blending of worldly and spiritual life.

While gold is often associated with permanence and opulence, in the context of Kinkaku-ji it takes on a different tone. The gilded upper stories shimmer in changing light—brilliant at noon, soft at dusk, and muted in winter snow. It is not static splendor, but a reminder that beauty lies in transformation. The surrounding garden, built in the kaiyū-shiki (stroll garden) style, reinforces this impermanence. Designed to be experienced on foot, the landscape reveals itself slowly: a rock here, a small waterfall there, a twisted pine that casts a changing shadow depending on the time of day.

Perhaps the most poetic expression of impermanence at Kinkaku-ji is its own history. In 1950, the pavilion was burned to the ground by a mentally ill monk—a shocking act that stunned the nation. But rather than erase the past, this tragedy became part of the structure’s narrative. The temple was painstakingly rebuilt in 1955, using traditional methods and careful historical research. While some debated whether a reconstruction could hold the same spiritual weight, the act of rebuilding itself became a testament to resilience. Just as cherry blossoms fall and return each spring, so too could the Golden Pavilion rise from ashes—its beauty deepened by loss.

This cycle of creation, destruction, and renewal speaks to a deeper aesthetic value in Japanese culture: wabi-sabi, the acceptance of transience and imperfection. While Kinkaku-ji gleams in literal gold, it exists in a tension with this philosophical ideal. Many critics have noted that its sister temple, Ginkaku-ji (the Silver Pavilion), better embodies wabi-sabi with its weathered wood and muted tones. Yet Kinkaku-ji, precisely because of its ostentation and subsequent ruin, invites a more complex contemplation of what it means to endure.

Literature, too, has engaged with the pavilion’s paradoxes. The 1956 novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Yukio Mishima fictionalizes the arson, exploring themes of obsession, beauty, and destruction. Mishima’s protagonist is haunted by the pavilion’s perfection, eventually concluding that he must destroy it to liberate himself from its tyranny. The novel reflects the darker undercurrents of aesthetic idealism—when beauty becomes unbearable, can destruction be a form of release? Through this lens, Kinkaku-ji becomes more than a building; it is an idea, an obsession, a mirror of the human psyche.

In art history, Kinkaku-ji also marks a pivotal moment in Kyoto’s visual culture. It signaled a shift away from aristocratic court styles toward a new synthesis of warrior taste, Zen spirituality, and cosmopolitan flair. The architecture and gardens influenced generations of temple construction and landscape design. Even today, contemporary artists and architects draw inspiration from its balanced asymmetry, symbolic layering, and ethereal light.

What makes Kinkaku-ji endure is not simply its beauty, but its contradiction. It is at once lavish and meditative, worldly and spiritual, rooted in history yet constantly reborn. It stands as a gleaming artifact of a shogun’s ego, a Zen monk’s devotion, and a nation’s capacity to transform tragedy into transcendence. In Kyoto—a city shaped by fire, war, and time—the Golden Pavilion reminds us that beauty need not be eternal to be eternal in meaning.

Tea Ceremony and the Art of Everyday Elegance

In the soft light of a Kyoto tea room, where the scent of tatami mingles with the steam of freshly whisked matcha, centuries of aesthetic philosophy converge in a single, simple gesture: the offering of a bowl of tea. The Japanese tea ceremony, or chanoyu, is often misunderstood as mere ritual, a performance of manners. But in truth, it is one of Japan’s most profound artistic achievements—a gesamtkunstwerk that synthesizes architecture, ceramics, calligraphy, lacquer, floral arrangement, and the seasonal rhythms of nature into a fleeting, intimate experience. And nowhere did this form evolve more fully than in Kyoto, the city where tea became art.

Though tea drinking had been introduced to Japan from China as early as the 9th century, it wasn’t until the Muromachi period that it began to take root among the cultural elite. Initially, the practice was ornate and ostentatious: tōcha (competitive tea tasting) and extravagant Chinese teaware were favored by samurai and aristocrats alike. These gatherings, known as shoin-style tea, often took place in elaborately decorated drawing rooms within Kyoto’s temple complexes or warrior residences. They were displays of wealth as much as taste.

But by the 15th and 16th centuries, Kyoto witnessed a quiet revolution—a movement away from grandeur toward simplicity and spiritual depth, driven by Zen Buddhism and embodied most fully by the tea master Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591). Though born outside Kyoto, Rikyū lived and worked in the city for much of his career, and it was in Kyoto that he distilled the tea ceremony into an art form rooted in humility, silence, and impermanence.

Rikyū’s aesthetic ideal was wabi, a concept that embraced imperfection, modesty, and the subtle beauty of the incomplete. Rather than using ornate Chinese porcelain, he favored rough-hewn Korean tea bowls, hand-formed and asymmetrical. Instead of gilded screens, he chose flickering candlelight and undecorated walls. His tearooms, known as sōan-chashitsu, were tiny huts barely large enough to accommodate host and guest, with low ceilings, small doorways (which required bowing), and rustic materials like bamboo, clay, and thatch. These intimate spaces created a deliberate retreat from the outside world, a place where time could pause and the essence of the moment could be savored.

One of the most famous examples of this style is the Tai-an tearoom in Kyoto’s Myōki-an temple. Believed to have been designed by Rikyū himself, it is a 2-tatami-mat room that exemplifies wabi-cha—a stripped-down, deeply contemplative mode of tea. Everything about the room is intentional: the alcove (tokonoma) for a seasonal scroll or flower arrangement, the rhythm of movements, the choice of utensils—all are curated to heighten awareness and sensitivity.

Tea gatherings, or chaji, followed a precise yet fluid structure. Guests would begin in a roji, or “dewy path” garden, symbolizing the transition from the mundane world to the sacred space of tea. Entering the tea hut, they would participate in a sequence of rituals: purification, appreciation of the utensils, a light meal (kaiseki), and finally the serving of thick tea (koicha) followed by thin tea (usucha). Yet within this structure, spontaneity and attentiveness were everything. A skilled host would subtly adjust the scroll, the flowers, or the serving ware to reflect the season, the time of day, or the emotional tone of the meeting.

The tea ceremony in Kyoto also fostered the development of a wide range of traditional crafts. Potters like Chōjirō, founder of the Raku family, began producing hand-molded tea bowls that embodied the wabi aesthetic. Their kilns, still active in Kyoto today, turned out vessels prized for their irregular shapes, deep glazes, and tactile warmth. Likewise, lacquer artisans crafted trays and tea caddies with subdued luster; bamboo masters fashioned whisks (chasen); metalworkers forged iron kettles (kama) with elegant restraint. These crafts, refined and elevated by the demands of chanoyu, were preserved in Kyoto’s tightly-knit artisan districts.

Calligraphy also found a central place in the tea room. A single scroll—often a Zen phrase or seasonal poem written by a monk—could set the entire tone of the gathering. The careful selection and presentation of such a scroll was an artistic act in itself, and Kyoto, with its monasteries and literary tradition, remained a crucial source of these works.

What made the tea ceremony more than an aesthetic indulgence, however, was its philosophical underpinning. Rikyū’s approach, though informed by Zen, was also deeply ethical and democratic. In the tea room, all participants—lord or servant—entered as equals. The host served and the guest received, with each gesture conveying respect, humility, and awareness. This ethos of mutual presence, of ichi-go ichi-e (“one time, one meeting”), transformed the tea room into a site of spiritual encounter.

By the Edo period, Kyoto had become the epicenter of tea schools, with major lineages like Urasenke, Omotesenke, and Mushanokōjisenke continuing Rikyū’s legacy. These schools formalized the practice of chanoyu, and their headquarters remain in Kyoto today, offering lessons, public demonstrations, and ceremonial events that continue to shape how tea is experienced both in Japan and abroad.

Even in the 21st century, the Kyoto tea ceremony endures—not as a nostalgic reenactment, but as a living, breathing art. Contemporary tea masters adapt the practice to new materials and spaces, while maintaining its core values of mindfulness, hospitality, and seasonal sensitivity. Architects design minimalist tea rooms in concrete and glass; artists craft bowls that challenge tradition while honoring its spirit.

In Kyoto, the tea ceremony is not confined to temples or museums. It appears in alleyway tea houses, university clubs, hotel gardens, and private homes. It infuses the city’s rhythms with quiet elegance, reminding residents and visitors alike that the most profound experiences often lie in the smallest, simplest acts—a shared bowl, a fleeting flower, a brief moment of silence.

Momoyama Period (1573–1615): Opulence and Power

The Momoyama period was brief but explosive—a moment in Japanese history when the arts, long tempered by restraint and ritual, erupted into brilliance under the patronage of ambitious warlords. In the wake of centuries of civil war, Kyoto became both a battleground and a canvas for the assertion of new power, expressed not just through swords and fortresses, but through gold, pigments, lacquer, and towering screens. The city—though ravaged during earlier conflicts—reemerged in the late 16th century as a resplendent hub of artistic reinvention, where luxury and political legitimacy merged in dazzling form.

At the center of this transformation was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a commoner-turned-supreme-ruler who rose through military ranks during the Sengoku period to unify most of Japan. Hideyoshi was not only a formidable general but a deeply image-conscious figure who understood that power could be projected through beauty. And Kyoto—still the seat of imperial prestige—was the ideal stage for this projection. With the emperor effectively reduced to symbolic status, warlords like Hideyoshi sought to legitimize their rule by aligning themselves with imperial rituals and artistic patronage, thereby turning art into a form of political theater.

One of Hideyoshi’s most enduring artistic legacies is the Jurakudai, his opulent palace constructed in Kyoto in the 1580s (now lost, but extensively documented). Adorned with lavish gold-leaf screens, painted sliding doors (fusuma), and sprawling gardens, the palace announced a new visual culture—bold, decorative, and unashamedly grand. It was a declaration of arrival for a new kind of ruler, unbound by the subtle aesthetics of the aristocracy or the disciplined minimalism of the Zen monks.

This new aesthetic found its most iconic expression in the Kano school, which rose to prominence under Momoyama patronage. While the Kano style had roots in the Muromachi period, it reached full maturity during this time, producing monumental artworks for castles and palaces. Artists like Kano Eitoku and his successor Kano Sanraku created enormous wall and screen paintings filled with gold backgrounds, powerful brushwork, and symbolic motifs—tigers, cranes, plum trees, and Chinese sages—meant to awe, instruct, and assert.

Kano Eitoku’s Chinese Lions or Cypress Tree screens, for example, are not just decorative—they exude strength, control, and a dynamic energy that mirrored the ethos of the warrior elite. The scale of these works, designed for architectural integration, transformed interiors into immersive environments of authority and splendor. The use of gold leaf, beyond its aesthetic appeal, also served practical functions: amplifying candlelight, warming cold rooms, and reflecting the temporal power of their patrons.

Architecture itself adapted to these theatrical demands. The shoin-zukuri style evolved into more elaborate forms, incorporating decorative alcoves (tokonoma), staggered shelves, and meticulously painted panels. This architectural vocabulary was designed to showcase art and host elite gatherings, blending the refined taste of the Kyoto aristocracy with the commanding presence of the new military class.

Yet Hideyoshi was not merely interested in interiors. He sought to inscribe his legacy into the very geography of Kyoto. His reconstruction of the Imperial Palace, commissioning of Daigo-ji’s cherry blossom viewing pavilions, and his massive project to renovate Toyokuni Shrine, dedicated to himself after his death, were all part of a grand strategy to transform Kyoto into a ceremonial and cultural capital that would reflect his own grandeur.

The tea ceremony, too, was absorbed into this politics of spectacle. Hideyoshi famously hosted a Grand Tea Ceremony in 1587 at Kitano Tenmangū Shrine in Kyoto, inviting nobles, monks, and commoners alike. He constructed an enormous gilded tea room—a far cry from Sen no Rikyū’s rustic huts—and surrounded himself with imported Chinese objects and lavish utensils. Yet even in this extravagance, he retained Rikyū as his tea master, acknowledging the deeper philosophical and aesthetic roots of chanoyu. Their eventual falling-out, culminating in Rikyū’s forced suicide, is often interpreted as a tragic collision between aesthetic humility and authoritarian ambition.

Beyond the confines of Kyoto’s palaces and temples, the Momoyama period saw a flourishing of crafts and decorative arts. Lacquerware became more elaborate, featuring makie designs with gold and silver powder. Ceramics—particularly Oribe ware and Shino ware—embraced irregular forms, vivid glazes, and a striking blend of rusticity and color. Kyoto kilns adapted to the new tastes by producing tableware and decorative vessels that were equal parts art object and statement piece.

The period also witnessed an increased interest in Namban art—works influenced by contact with Portuguese and Spanish missionaries. Folding screens depicting Westerners in exotic dress, Christian iconography rendered in Japanese techniques, and hybrid architectural motifs began to appear, especially in port cities, but traces of this cultural contact found their way into Kyoto as well. These images underscored the expanding world of the late 16th century and Kyoto’s role as a crossroads of both tradition and novelty.

Though the Momoyama period ended with the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate and the shift of political power to Edo, its visual legacy endured. Kyoto remained a center for the Kano school, tea lineages, and the preservation of the opulent styles developed during this time. The bold colors, asymmetrical compositions, and synthesis of decorative and architectural art continued to influence everything from Nō stage design to kimono patterns.

In many ways, the Momoyama period was Kyoto’s Baroque moment—a time when political consolidation and personal ambition were expressed through grand, theatrical artistry. But beneath the surface glitter lay a deep engagement with legacy, place, and power. It was not just a show of wealth—it was a reimagining of Japanese aesthetics in the language of conquest and consolidation. And as ever, Kyoto stood at the center: the stage, the script, and the setting for this extraordinary chapter in the art history of Japan.

Edo Period: Art for the People

By the dawn of the Edo period (1603–1868), Kyoto was no longer Japan’s political capital, yet it remained its beating cultural heart. With the Tokugawa shogunate headquartered in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), Kyoto transitioned into a different kind of artistic role—not as the center of power, but as the cradle of refinement, craft, and cultural continuity. Unlike the spectacle-driven arts of the Momoyama period, Edo-era Kyoto witnessed a democratization of artistic expression. Art was no longer confined to aristocrats and warlords; it found its way into the lives of merchants, townspeople, and artisans. It was an era of expansion and accessibility—a golden age of “art for the people.”

Kyoto’s position as a former imperial city endowed it with a sense of authority and legitimacy, even as political clout shifted elsewhere. The emperor still resided there, and with him remained the court traditions, court poets, calligraphers, and a constellation of artisans bound to centuries-old practices. This preserved legacy helped define Kyoto’s distinct cultural identity within the larger Tokugawa system. While Edo was characterized by bustling innovation, Kyoto offered continuity—a tether to the elegant, spiritual, and aesthetic values of Japan’s classical past.

But continuity did not mean stagnation. Kyoto was a thriving urban center, and during the Edo period it became a flourishing city of craft guilds, printmakers, textile workshops, and performing arts. This cultural energy gave rise to a localized form of popular art that, while often overshadowed by the more commercially driven Edo scene, deserves recognition for its nuance and sophistication.

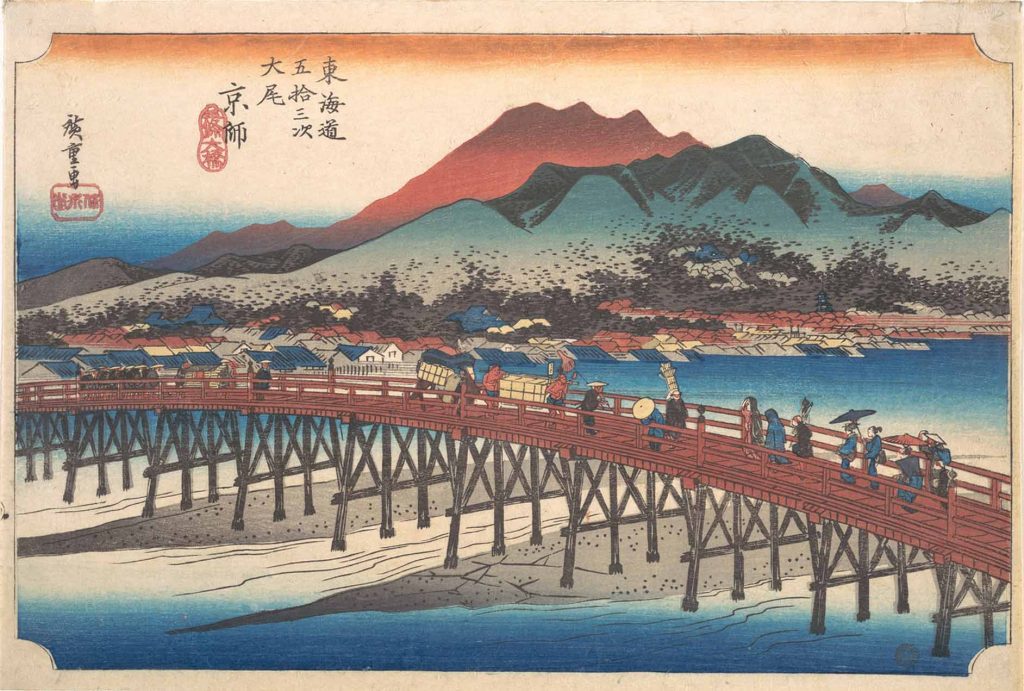

One of the most recognizable genres of Edo-period art is ukiyo-e—the “pictures of the floating world.” Though commonly associated with Edo and artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige, Kyoto developed its own distinct ukiyo-e tradition. The Kyoto School of printmaking, centered in areas like Nishijin and Shijō, often exhibited a more lyrical, subdued style compared to the flashier images of Edo’s pleasure quarters. Artists like Nishikawa Sukenobu, for example, were known for their elegant depictions of women engaged in everyday activities—reading, writing, arranging flowers—imbued with a quiet grace that echoed Heian sensibilities.

Unlike Edo’s mass-market prints, many Kyoto ukiyo-e works were published in smaller runs and sold to a more refined clientele. They often blurred the line between popular and high art, with careful attention to line quality, pattern, and composition. Some prints included poetry, calligraphy, or even literary references, creating a kind of hybrid art object that spoke to Kyoto’s scholarly and aesthetic traditions.

The textile arts in Kyoto also thrived during this time, driven by the demands of both the imperial court and the burgeoning merchant class. The Nishijin district, in particular, became world-renowned for its intricate silk weaving. Nishijin-ori, with its complex brocade patterns and luxurious materials, adorned everything from kimono to Nō costumes. Textile design itself became an art form, with weavers collaborating with painters and calligraphers to create bolts of fabric that were as much visual art as functional material.

Alongside weaving, Kyoto remained a major center for yuzen dyeing, a resist-dye technique used to create intricate, hand-drawn designs on silk. Developed in the 17th century by the artist Miyazaki Yūzen, the technique allowed for painterly motifs—flowers, birds, landscapes—to be rendered in vibrant detail on garments. These kimono were not simply fashion; they were wearable art, often telling stories or referencing poetry. The Kyoto style favored subtle, elegant compositions compared to the bold, colorful designs popular in Edo.

Another defining art form of the Kyoto Edo period was rimpa, a decorative painting school that combined classical themes with dramatic compositions and luxurious materials. Founded by Hon’ami Kōetsu and later developed by Ogata Kōrin, rimpa artists worked in Kyoto and often collaborated with lacquerware, ceramics, and textile artisans. Kōrin’s famous Red and White Plum Blossoms screen, with its gold-leaf background and stylized river, epitomizes the rimpa aesthetic: bold yet refined, rooted in classical poetry but modern in its visual rhythm.

Kōetsu’s legacy also extended into calligraphy, ceramics, and the tea ceremony. In Kyoto’s northern hills, he established an artist community in Takagamine, where painters, potters, and calligraphers lived and worked together. This fusion of art forms reflected the Kyoto ethos of holistic creativity, where the boundaries between “fine” and “applied” arts dissolved in the pursuit of beauty and harmony.

In terms of performing arts, Kyoto remained the stronghold of Nō theater and Kabuki, both of which were heavily intertwined with visual aesthetics. Costumes, masks, and stage sets were all designed by local artisans, whose work often reflected broader trends in painting and textile design. The city also saw the rise of bunraku puppet theater, whose miniature sets and finely crafted puppets were marvels of artistic precision.

Even as Edo and Osaka grew into commercial powerhouses, Kyoto retained its stature through the codification of taste. Manuals on tea ceremony, flower arrangement, incense appreciation, and etiquette were published and disseminated throughout the country, many originating in Kyoto. These guides helped to standardize aesthetic values, making Kyoto not only a producer of art but also an arbiter of style.

Crucially, the Edo period’s strict social order paradoxically enabled this artistic flourishing. With relative peace under Tokugawa rule, Kyoto’s artisans and merchants found stability, patronage, and a growing market for their work. Artisans formed guilds, trained apprentices, and passed down techniques that had been refined over generations. Many of these crafts survive to this day, with some families continuing unbroken lineages for over 400 years.

By the close of the Edo period, Kyoto had firmly established itself not just as a historical capital, but as a living repository of cultural memory. Its ukiyo-e, textiles, lacquerware, ceramics, and architecture collectively embodied the idea that beauty could—and should—permeate daily life. Art was no longer confined to palaces and temples; it appeared on folding fans, obi sashes, shop signs, and seasonal confections. Kyoto had made aesthetic experience an integral part of ordinary existence, ensuring that the floating world would not simply drift away, but anchor itself in the textures of daily life.

Meiji Restoration and the Struggle Between Tradition and Modernity

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 marked a seismic shift in Japanese history. With the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the restoration of imperial rule under Emperor Meiji, Japan entered a period of rapid modernization and Westernization. Railways replaced roads, gaslights displaced lanterns, and military uniforms supplanted samurai armor. Amid this national transformation, Kyoto—a city built on centuries of cultural tradition—faced an existential question: Could it preserve its artistic soul while adapting to a new world?

The answer, as history would show, was a complicated and often precarious balancing act. On the one hand, the Meiji government actively dismantled the feudal structures that had sustained Kyoto’s artistic and religious institutions. Temples and shrines lost land and income through the haibutsu kishaku (“abolish Buddhism, destroy Shakyamuni”) movement, which aimed to sever Buddhism’s ties to the old order. Many artworks were destroyed, hidden, or sold abroad. The artisan guilds, long supported by aristocratic and warrior patrons, found themselves economically vulnerable. As the imperial court moved to Tokyo, Kyoto lost its symbolic role as the heart of the nation, triggering a cultural and economic crisis.

Yet it was precisely in this moment of upheaval that Kyoto began to reassert itself—not as a political capital, but as the custodian of traditional Japanese art. Recognizing the risk of cultural erosion, a coalition of scholars, artists, and officials began to document, preserve, and promote the city’s vast artistic heritage. Their efforts gave birth to institutions that still shape Kyoto’s artistic landscape today.

One of the most significant developments was the founding of the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting in 1880, which would eventually evolve into the Kyoto City University of Arts, the oldest municipal art school in Japan. The school was intended not only to train artists but to preserve traditional techniques while allowing for innovation. It became a haven for Nihonga (Japanese-style painting), a genre that combined classical methods—like mineral pigments, gold leaf, and washi paper—with contemporary subjects and perspectives. Artists like Takeuchi Seihō and Tomita Keisen, based in Kyoto, helped define this new visual language, balancing reverence for the past with engagement in the present.

At the same time, Kyoto artisans faced the challenge of competing in a global market increasingly dominated by industrialized goods. Some responded by rebranding tradition as luxury. Kyoto’s textile weavers, ceramicists, lacquer artists, and metalworkers adapted their crafts for international expositions, exporting Nishijin silks, Kyō-yaki porcelain, and makie lacquerware to Europe and the Americas. These works, often made for foreign tastes, were more ornate and technical than their Edo-period predecessors, signaling a subtle shift from cultural ritual to commercial enterprise.

One of the figures who epitomized this adaptive spirit was Namikawa Yasuyuki, a Kyoto cloisonné master whose enamel works gained global acclaim for their refinement and innovation. Using transparent enamels and subtle shading techniques, Namikawa elevated cloisonné to fine art, winning medals at world’s fairs and setting a new standard for Japanese decorative arts. His workshop in Kyoto, now preserved as a museum, is a testament to how traditional techniques could be fused with modern aesthetics to create something globally resonant.

Preservation was also institutionalized. In 1889, the Kyoto National Museum (then the Imperial Museum of Kyoto) was established to collect and exhibit classical Japanese art. It became a vital site for both scholarship and public engagement, housing temple treasures, calligraphy, paintings, and ceramics that otherwise risked being lost to the pressures of modernization or the international art market.

Yet Kyoto’s cultural revival wasn’t limited to elite institutions. The Meiji period saw the emergence of a civic pride in craftsmanship, with neighborhoods like Gojōzaka and Nishijin actively cultivating their artisanal identities. These districts became living archives, where artisans passed down their knowledge through apprenticeships, adapting their output to new demands—decorative household goods, boutique accessories, and even tourist souvenirs.

In tandem with preservation came reinvention. Kyoto architects and designers began to explore how Western technologies and materials could be harmonized with Japanese spatial philosophy. The Kyoto Imperial Museum, built in a French Renaissance style, was juxtaposed against the surrounding temple architecture, a physical symbol of Kyoto’s new hybridity. Local carpenters began incorporating glass, steel, and imported hardware into traditional machiya (townhouses), creating a built environment that was neither wholly past nor wholly present.

The tensions of the period were not without pain. The loss of courtly patronage, the erosion of temple incomes, and the commodification of spiritual objects led to both cultural losses and identity crises. Kyoto artists and craftspeople were forced to wrestle with uncomfortable questions: Was tradition enough? Could beauty survive without ritual? What was the value of heritage in a society increasingly obsessed with progress?

Some resisted. Others adapted. And many did both—preserving the heart of their art while letting the form evolve. In this crucible of change, Kyoto emerged not as a relic of a vanished Japan, but as its cultural conscience: a city that reminded the nation of its aesthetic lineage even as it stepped into the modern world.

By the end of the Meiji period, Kyoto had redefined its role. No longer the center of power, it had become the guardian of artistic integrity, a place where tradition was not merely preserved but rearticulated for new generations. This legacy would carry into the 20th century and beyond, ensuring that even in an era of railways and factories, a hand-shaped tea bowl, a brush-drawn pine tree, or a lacquered comb could still carry the weight of centuries.

Modern and Contemporary Kyoto Artists

As the 20th century unfolded, Kyoto found itself at a crossroads once again. The Meiji era had been a time of urgent adaptation, but the modern era brought with it new complexities—two world wars, rapid urban development, and the globalization of culture. Yet through these upheavals, Kyoto remained not just a city of preservation, but one of quiet reinvention. In this chapter of its art history, Kyoto fostered a generation of painters, designers, and multimedia artists who honored tradition even as they challenged its boundaries. The result was a rich, often paradoxical modernism: rooted in the past, responsive to the present, and alert to the possibilities of the future.

At the center of this evolution was Nihonga—Japanese-style painting—a movement that had emerged in the Meiji period and found fertile ground in Kyoto. While Tokyo artists often pushed for dramatic Westernization, Kyoto’s Nihonga painters sought a fusion of innovation and continuity. One of the most prominent figures in this regard was Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942), a Kyoto native who studied both traditional yamato-e and Western realist techniques. His work, such as Elephant or Lion, exemplifies the hybrid style that came to define Kyoto Nihonga: naturalistic form rendered in mineral pigments and ink, with a compositional restraint that echoed Zen principles.

Takeuchi was not alone. Other Kyoto-based Nihonga masters like Uemura Shōen, one of the first prominent female painters in Japan, brought a new dignity and emotional depth to the portrayal of women—her Bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women) eschewed the decorative for the contemplative. Inshō Dōmoto, another major figure, blended abstract design with classical motifs, producing screen paintings and murals that radiated both spiritual energy and modernist elegance. His later work, particularly after World War II, incorporated bold color fields and non-figurative forms, positioning him as a bridge between classical Japanese aesthetics and international abstraction.

Dōmoto’s impact on Kyoto’s cultural landscape extended beyond the canvas. In 1966, he founded the Domoto Insho Museum of Fine Arts in Kyoto’s northern hills—a space designed by the artist himself, where architecture and exhibition coalesce in harmony. His example inspired other artists and curators to see Kyoto not just as a place of memory, but as a platform for contemporary expression within traditional frameworks.

Throughout the 20th century, Kyoto also developed a dynamic craft-based modernism. Ceramics, lacquer, textiles, and metalwork—long categorized as “applied arts”—were elevated to fine art through the vision of artists who defied the binary. Kondō Yūzō, for example, reimagined blue-and-white porcelain (traditionally associated with Chinese imports) through asymmetry and abstract glazing. Tomimoto Kenkichi, a Kyoto-based ceramicist and a leading advocate of the Mingei (folk art) movement, blended the rustic ethos of handmade objects with modern design principles. His influence extended into education: as the first head of the ceramics department at Kyoto City University of Arts, he shaped generations of potters to think beyond form and function.

By the postwar era, Kyoto had become a hub for artistic experimentation. The city’s art universities—Kyoto City University of Arts, Kyoto Seika University, and Kyoto University of the Arts (formerly Kyoto University of Art and Design)—nurtured both traditional apprenticeships and avant-garde explorations. The Sōdeisha ceramic collective, founded in Kyoto in 1948, rejected utilitarian pottery in favor of sculptural forms. Artists like Yagi Kazuo and Suzuki Osamu created non-functional, abstract ceramic pieces that blurred the line between vessel and sculpture, redefining what clay could express in the modern world.

Kyoto’s artists also responded to global trends in conceptual and installation art, often by reinterpreting local materials and rituals. The use of washi paper, bamboo, gold leaf, and natural pigments found new life in minimalist installations and spatial experiments. Contemporary artist Tanaka Kyokusho, for instance, infuses calligraphy with performance and abstraction, transforming brushwork into movement and meditation. Others, like Kyotaro, bridge manga illustration, mysticism, and street culture, creating a new visual language that resonates with younger audiences while still drawing on Kyoto’s traditional visual codes.

Institutions like the Kyoto Art Center, housed in a former Meiji-era school, have become incubators for experimental art, hosting residencies, exhibitions, and performances that connect Kyoto’s past with global contemporary discourse. Similarly, the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, recently renovated and rebranded as Kyocera Museum of Art, now houses both historical collections and cutting-edge exhibitions, signaling the city’s continued commitment to living tradition.

What distinguishes modern and contemporary Kyoto artists is not simply their mastery of materials, but their philosophical approach. Whether crafting a tea bowl, staging an installation, or composing a screen painting, they operate with an acute awareness of impermanence, tactility, and the dialogue between object and space. This approach is deeply rooted in Kyoto’s artistic DNA—a legacy of Zen, wabi-sabi, and seasonal sensitivity.

Today, Kyoto’s art scene thrives in unexpected places: in tiny galleries tucked behind noren curtains, in design studios balancing tradition with technology, in avant-garde theater troupes performing on tatami mats. The city’s dual identity—as a preserver of history and a maker of the new—offers a model for how culture can evolve without rupture. Kyoto does not reject modernity; it absorbs it, refracting it through centuries-old lenses to create something distinctly, defiantly its own.

In a world often driven by speed and novelty, Kyoto’s artists continue to insist on the power of slowness, intimacy, and material intelligence. Their work reminds us that the modern need not erase the traditional, and that the future can be shaped as much by memory as by momentum.

Craft Traditions and the Living National Treasures

In Kyoto, the boundary between art and craft dissolves into a philosophy of living beauty. Here, a tea bowl is not just a vessel but a tactile expression of wabi; a bolt of hand-dyed silk is not just fabric but a reflection of the seasons, skill, and spirit. For over a millennium, Kyoto has nurtured Japan’s most exquisite craft traditions, many of which survive not as museum relics but as living practices passed down through generations. These crafts are more than decorative—they are embodiments of technique, memory, and human presence. And central to their preservation and elevation in modern Japan is the concept of the Living National Treasure (Ningen Kokuhō), a title bestowed upon individuals who represent the pinnacle of traditional craftsmanship.

The postwar Japanese government, recognizing the vulnerability of its intangible cultural assets amid modernization, instituted the Cultural Properties Protection Law in 1950. Within this framework, certain craftspeople could be designated as Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Properties—colloquially known as Living National Treasures. Kyoto, with its deep artisanal heritage, has produced more of these individuals than almost any other city in Japan.

Among Kyoto’s most renowned crafts is Nishijin weaving, a complex textile tradition dating back over 1,000 years. Originating from the imperial demand for court garments, Nishijin-ori combines silk threads, gold leaf, and brocade techniques to produce fabrics of unparalleled intricacy and luster. The process requires multiple artisans—designers, dyers, weavers, and finishers—often working in neighborhood workshops that dot the Nishijin district. Katsura Yūzō, one of Kyoto’s most celebrated Nishijin weavers, was designated a Living National Treasure for his preservation of this labor-intensive tradition. His works, which often include motifs from nature and classical literature, are as intellectually rich as they are materially sumptuous.

Equally revered is Kyoto’s tradition of Kyo-yaki and Kiyomizu-yaki ceramics. Rooted in the hills of eastern Kyoto, near Kiyomizu-dera temple, these ceramics range from rustic tea bowls to elaborately painted porcelain. Artists such as Matsui Kōsei, honored as a Living National Treasure for his mastery of nerikomi (layered colored clay), elevated ceramics into realms of abstraction and precision. His works, though sculptural in their refinement, retain a quiet humility grounded in Kyoto’s tea and Zen culture.

Another indispensable thread in Kyoto’s craft heritage is Kyo-shikki, or Kyoto lacquerware. Known for its delicate brushwork, subtle use of gold and silver, and restrained elegance, Kyo-shikki adorns everything from tea utensils to writing boxes. Master lacquerer Ikeda Taishin, designated as a Living National Treasure in the early 20th century, was instrumental in preserving the ancient makie (sprinkled gold) technique while adapting it to modern forms. The shimmering surfaces of his works, layered through months of application and polishing, demonstrate a devotion to time and tactility rarely found in the contemporary world.

The city is also home to artisans of Kyo-komon (fine-dotted dyeing), Kyo-kanoko shibori (tie-dye), Kyo-yūzen (hand-painted kimono fabric), and Kyo-gashi (seasonal confectionery), each with its own network of masters and apprentices. In these crafts, innovation lies not in disruption but in deeper articulation. Patterns are subtly adjusted, colors slightly modulated, techniques quietly perfected. Change is gradual and organic—a spiral, not a rupture.

What makes Kyoto’s craft culture particularly resilient is its embeddedness in daily life and ritual. Unlike fine art, which often lives in galleries, Kyoto’s crafts are used and encountered—on tatami floors, in lacquered bento boxes, through hand-folded fans at summer festivals, or in the worn fabric of a kimono passed down across generations. This intimacy ensures that craft is not only preserved but loved, maintained through use rather than abstraction.

Festivals like the Gion Matsuri serve as living theaters for these crafts. Each yamaboko float is a mobile museum, adorned with ancient textiles, gilded carvings, and painted panels—many produced by Kyoto artisans past and present. The festival’s collaborative nature mirrors the structure of Kyoto’s craft world: interdependent, rooted in place, and deeply communal.

Today, Kyoto’s Living National Treasures continue to teach and exhibit, often working out of modest homes or workshops nestled between temples and machiya townhouses. They are not celebrities, but custodians—teachers in the truest sense, preserving not just skills, but values. Their designations often extend beyond personal acclaim to elevate entire crafts, ensuring institutional support, funding, and interest from younger generations.

Art schools in Kyoto, such as Kyoto City University of Arts and Kyoto University of the Arts, actively collaborate with these masters, creating programs where students can learn both traditional methods and contemporary applications. Meanwhile, galleries like Gallery Gallery, Kōgei Contemporary, and the Kyoto Museum of Traditional Crafts serve as bridges between artisan traditions and the contemporary art world.

In a global art climate often dominated by speed, scale, and spectacle, Kyoto’s crafts offer a counter-narrative: one of slowness, precision, humility, and intergenerational continuity. They challenge the modern assumption that art must always innovate to be relevant. Instead, they remind us that refinement—done patiently and with deep attention—can be as radical as any rupture.

Kyoto’s craft traditions, sustained by Living National Treasures and countless unnamed apprentices, tell a story not only of material beauty but of human fidelity: to process, to place, and to the unseen labor of hands. In every thread, glaze, or lacquered curve lies a quiet revolution—one that insists that meaning is made not by novelty, but by care.

Kyoto Today: Art in the Old Capital

In Kyoto, time folds. The past is never quite past; it lingers in every alleyway, temple gate, and handmade brushstroke. Yet Kyoto is not a city content to live as a relic. In the 21st century, it has become a dynamic stage where tradition and innovation coexist, often in tension, but more often in harmony. Today, Kyoto’s art scene is not a museum—it is a living ecosystem, where calligraphy shares space with contemporary installations, and a 400-year-old textile workshop might sit beside a digital art lab. In this final chapter, we explore how Kyoto continues to be Japan’s artistic conscience: deeply historical, defiantly contemporary, and quietly revolutionary.

One of Kyoto’s great strengths is its ability to integrate the new into the old without erasure. Walking through the city, one might stumble into a minimalist architecture studio housed in a restored machiya, or find a cutting-edge gallery beneath the eaves of a former sake brewery. Institutions like the Kyoto Art Center, based in a converted Meiji-era elementary school, offer residencies and workshops that support artists working across media, from ceramics and dance to coding and performance art. These spaces encourage experimentation, but always with a dialogue—explicit or implicit—with Kyoto’s artistic heritage.

This ethos is embodied in Kyoto’s contemporary gallery and museum culture. The Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, reopened in 2020 after a major renovation, now stands as a bold architectural and curatorial bridge between eras. Its exhibitions range from retrospectives on Kyoto School painters to immersive new media installations, often inviting cross-generational and interdisciplinary conversation. Similarly, smaller spaces like Gallery Morning, Kahitsukan Museum of Kyoto, and Hakuichi highlight emerging artists alongside established craftspeople, breaking down hierarchies between fine art and applied arts.

The Kyotographie International Photography Festival, launched in 2013, is another vivid example of Kyoto’s global engagement. Held each spring, the festival transforms temples, townhouses, and former kimono warehouses into unconventional galleries. International and Japanese photographers exhibit side-by-side in these atmospheric spaces, often tailoring their work to the architecture and cultural context. The festival is not only a showcase of global contemporary photography—it is an act of spatial storytelling, a citywide exhibition rooted in place.

Kyoto’s educational institutions continue to shape its artistic future. Kyoto City University of Arts, Kyoto Seika University, and Kyoto University of the Arts all nurture new generations of creators, many of whom are eager to collapse the artificial boundaries between “traditional” and “contemporary.” Courses in textile arts, ceramics, metalwork, and Nihonga sit alongside experimental media, manga, and conceptual practices. It is not uncommon to see a student developing AI-generated art while referencing Heian poetry or crafting a digital installation with handmade washi paper.

The city also fosters a robust independent maker movement. Kyoto’s deeply embedded craft traditions have found new expression through designers and artisans who blend heritage with modern design thinking. Studios like Kamisoe (handmade paper and stationery), Kaikado (handmade tea caddies), and Miyawaki Baisenan (traditional fans) collaborate with architects and fashion designers to reimagine everyday objects as contemporary artifacts. Many of these workshops open their doors to visitors, offering demonstrations and participatory experiences that transform commerce into cultural education.

Technology plays an increasingly central role. Kyoto’s creative tech sector—home to companies like Nintendo and a cluster of design startups—has begun to intersect with traditional arts. Artists explore augmented reality in temple gardens, reimagine Nō theater through projection mapping, or build interactive sound installations inside heritage spaces. Far from rejecting tradition, these projects often frame it as a canvas for new forms of sensory and conceptual exploration.

Kyoto is also a city of seasonal and site-specific art, a sensibility drawn from centuries of attention to nature and impermanence. Contemporary artists frequently respond to cherry blossom cycles, moon phases, or the shifting tone of light across temple roofs. This attunement to atmosphere—not just subject matter—is one of Kyoto’s most enduring aesthetic contributions. Whether in a temporary exhibition at Kyoto Saga Arashiyama Museum of Arts & Culture or a candlelit performance at Kodai-ji Temple, time and space are treated not as neutral backdrops, but as active participants in the artistic encounter.

One must also acknowledge Kyoto’s role as a global artistic pilgrimage site. Creators from around the world come to Kyoto to study, teach, or immerse themselves in its crafts, philosophy, and rhythm. The Villa Kujoyama, a French-Japanese residency program, hosts artists working across disciplines in a serene, mountaintop setting designed to encourage deep dialogue with Japanese culture. These artists, in turn, carry Kyoto’s influence into their own practices, extending the city’s reach far beyond Japan’s borders.

Yet even amid this openness, Kyoto retains a protective instinct toward its artistic heritage. This is not conservatism, but a kind of cultural ecology. The city understands that innovation must be metabolized slowly, with reverence. Artistic change is not a rupture, but a seasonal cycle—something to be observed, guided, and eventually absorbed. It is an attitude that values craft over spectacle, subtlety over provocation, and relationship over fame.

In Kyoto today, the past is not a weight—it is a wellspring. Whether etched into the stone steps of Gion, fired into the glaze of a Raku bowl, or coded into the pixels of a digital screen, it continues to nourish new creation. The city is not fixed in time but folded through it, offering each generation the chance to begin again—with brush, chisel, lens, or line.

Here, art is not just made. It is lived.