In the decades before Kentucky achieved statehood in 1792, the region’s art was neither formal nor ornamental. It was practical, intimate, and deeply tied to the necessities of settlement. Visual expression, in these early years, emerged not from studios but from barns, cabins, forts, and churches. What we call “art” from this period did not separate itself from daily life. It was carved into tools, painted onto wagon panels, stitched into coverlets, and built into chimneys and gates.

Pioneer Iconography and Settlement Landscapes

The earliest visual culture in Kentucky was rooted in survival. It came from men and women who crossed the Cumberland Gap carrying rifles, axes, and perhaps a single family heirloom—rarely a painting or sculpture. Unlike cities on the Eastern Seaboard, which quickly developed academies, newspapers, and salon-style collections, frontier Kentucky had to invent its own visual language.

This was a land where symbolism was direct and legible. A star etched on a powder horn, a whittled bear atop a fence post, or a house painted with red clay and buttermilk—the meanings were not coded, they were embedded in the thing itself. The decorative motifs of early Kentucky cabins often had European antecedents (especially German, Scots-Irish, and English), but they were radically simplified. Geometric panels, chamfered beams, and starburst carvings served both structure and statement.

One of the few surviving examples of early pictorial work from pre-statehood Kentucky is a small group of hand-drawn maps and cabin plans—some sketched with charcoal, others inked with walnut dye. They show not only property lines and defensive positions, but rivers, tree stands, and the symbolic outlines of cornfields. Here, land itself became the canvas, and mapping was as much an act of faith as a legal document.

Surveyors, Masons, and Mapmakers as Early Visual Craftsmen

The earliest trained hands on the frontier were not painters or sculptors, but surveyors and masons. Figures like Daniel Boone, while legendary for their wilderness exploits, also engaged in the meticulous craft of topographical drawing. Boone’s maps, as well as those of his contemporaries, reveal a visual intelligence that has largely been forgotten: the ability to translate space, elevation, and danger into symbolic form with minimal tools.

Masons, meanwhile, brought with them the techniques of stonelaying and timber framing that had shaped rural England and Germany. They inscribed their own initials, dates, and motifs into hearthstones, lintels, and foundations. These marks, often mistaken for mere decoration or builder’s graffiti, were in fact part of a language of continuity—linking structures to their makers and their lineage. Every keystone was a kind of signature.

One revealing document from the 1780s is a ledger kept by a stonecutter near Harrodsburg, which includes drawings of gravestone designs alongside names, dates, and costs. The motifs—wheat sheaves, eyes, clasped hands—were drawn from a shared visual lexicon carried westward. These markers stood alone on hilltop burial plots, stone sentinels in otherwise unwritten country.

Decorative Objects from Cabin to Courthouse

What survives from this period is scattered, private, and mostly functional. Painted chests, hand-carved banisters, and needlework samplers carry traces of a regional aesthetic—one defined not by formal schools or manifestos, but by hand, repetition, and usefulness.

Three forms in particular reflect the nascent art culture of pre-statehood Kentucky:

- Painted dower chests: Often made from local walnut or poplar, these boxes were sometimes decorated with stylized flowers, birds, or geometric patterns. Their decoration was a form of courtship and legacy, passed from mother to daughter. Many bear initials and dates in hand-cut block letters.

- Hornbooks and Bible pages: Education, where it existed, took visual form through rudimentary hornbooks—wooden paddles covered with paper and thin cow horn, often decorated with border drawings or marginalia. Pages from Bibles and prayer books were hand-illuminated with red and blue inks, especially when passed down between generations.

- Tombstones and milestones: These were among the few fixed visual markers in a shifting world. Unlike the ornamental funerary sculpture of later decades, frontier grave markers were often slabs with deeply incised lines, thick with wear and moss, yet unmistakably human in their proportions.

Though the settlers of Kentucky were not interested in “art” in the way Boston or Philadelphia might have understood it, they understood the power of visual form. They cut it into their tools, stitched it into their cloth, laid it into their foundations. Every axe handle shaped just so, every cornice line rising against the woods, was part of an emerging artistic tradition built from necessity, skill, and memory.

Toward the end of the 18th century, as towns like Lexington and Louisville began to take shape, this rough-hewn visual culture began to evolve. Roads were laid, inns built, schools opened. People began to stay in one place longer, to own more, to decorate more. But the foundations of Kentucky’s artistic history—its honesty, its preference for material over theory, its fusion of skill and symbolism—were set firmly in this earliest period.

It would be years before the region produced painters of national reputation or housed proper galleries. But the Kentucky eye, trained on land and utility, was already forming—quietly, rigorously, and without pretension.

The Agrarian Eye: Portraiture and Land in the Early 19th Century

Kentucky entered the 19th century with land on its mind and labor in its bones. The frontier had begun to settle, and with settlement came pride—pride in acreage, livestock, fences, lineage, and survival. It was in this context that painting began to separate itself from pure craft. While still deeply tied to use and memory, art in early 19th-century Kentucky turned increasingly toward representation: of faces, of farms, of possession itself. Portraiture and landscape painting rose in tandem, not in the salons of the coasts, but over hearths and parlor mantels.

Farmsteads, Fences, and Painted Pride

Unlike the theatrical portraits found in the urban East—where wealth might be suggested by velvet drapery or classical columns—Kentucky portraiture was tied to the soil. A man’s boots, a woman’s apron, the hills behind a split-rail fence: these were the badges of identity. Pride was expressed not in borrowed European tropes, but in painted cows, bluegrass meadows, and the glint of a well-ploughed furrow.

Itinerant artists traveled from county to county, offering portraits at modest rates. Few of these painters received formal training, though many were adept technicians. They developed distinctive, often charmingly rigid styles, shaped by local preference rather than academic standards. Limbs were stiff, hands oversized, backgrounds flat. But the effect was not naive—it was deliberate. A Kentuckian’s painted face in 1825 was not meant to flatter or impress; it was meant to endure.

One such painter, Patrick Henry Davenport, worked across central Kentucky in the 1830s, producing small oil portraits of farmers, storekeepers, and ministers. His style was spare but precise: subjects often appear seated stiffly against dark, neutral backgrounds, eyes slightly wide, clothing rendered in coarse but accurate folds. What makes his work compelling is its lack of affectation—his subjects appear not as they might wish to be, but as they were. His records, preserved in a Mercer County ledger, show that many portraits were paid for in chickens, fence posts, or sacks of cornmeal.

This barter system was part of the economy of representation in early Kentucky. People did not commission portraits to display sophistication, but to secure memory. It was a form of permanence—like a grave marker or a barn beam. You left a likeness so your children, and theirs, would know your face. And often, your land would be painted with you.

Folk Portraitists and Itinerant Painters

The most distinctive visual tradition of this period came from the hands of the unnamed or little-known “folk” painters whose work, only generations later, would be rediscovered and admired for its clarity, stillness, and tactile presence. These artists filled the homes of Kentucky’s growing agrarian class with images that were plainspoken, symmetrical, and often oddly beautiful.

A vivid example is the so-called “Bluegrass School”—not an institution, but a loosely grouped series of painters working in the central counties during the 1820s–1850s. While often dismissed by coastal critics of the time as provincial, their work had a staying power grounded in realism and restraint. Faces were sometimes idealized, but more often showed the marks of work and age. Backgrounds featured tobacco barns, livestock pens, or the family springhouse. Even within the confines of oil on board or canvas, these painters recorded a visual culture in transition—from survival to stewardship.

Women were sometimes painted holding hymnals or needlework, men with tools, books, or crops. Horses appear often, especially in portraits commissioned near Lexington—already the emerging capital of equine breeding and the elite pasture economy. These paintings were not indulgences; they were records, rewards, and proof of standing.

It was during this period that certain visual tropes became standard in Kentucky portraiture:

- The three-quarter seated pose, usually against a dark or brown backdrop, sometimes with a small side table showing a single letter or object of personal significance.

- The landscape-through-window motif, in which a farming scene or property view is subtly inserted into the upper corner or background, showing the sitter’s land as part of their identity.

- The single-room interior, emphasizing sparse furnishings and suggesting domestic order and restraint rather than wealth or comfort.

Land Ownership and the Visual Grammar of Permanence

As Kentucky’s counties expanded and towns developed, ownership began to define both status and aesthetics. A man’s name on a deed became as important as the number of acres he held. That sense of rootedness—of owning a specific plot of soil and cultivating it with intention—was mirrored in the art of the time.

Landscape painting took on a dual role: it served as both document and declaration. A painted farm was not just scenery—it was a signature. These paintings were usually small, intended for home display rather than exhibition. They emphasized borders, fences, livestock, and topography. A line of sugar maples along a fence, a hayrick beside a field of sorghum, a dog asleep under the shade of a corncrib—these details were deliberate, placed to establish continuity between subject and soil.

One surviving example from 1842, painted by an anonymous artist in Garrard County, shows a broad, shallow valley with an L-shaped log home, a smokehouse, and five penned sheep in the foreground. In the distance, the outlines of a tobacco barn and a ridge of hickory trees. The family is shown in the center, clustered but not idealized. The painting is quiet, even austere—but full of assertion. “This is ours,” it seems to say. “And we are still.”

This period also saw the rise of courthouse art—murals, maps, and printed illustrations designed to hang in public buildings and land offices. These images, while less personal, reinforced the same aesthetic values: order, settlement, ownership, and legacy. They depicted not wild woods or mythical scenes, but gridded fields, orderly roads, and the slow conquest of brush and bramble by plow and surveyor’s chain.

The early 19th century was not a golden age in the sense of excess or recognition. But it was a time when the artistic eye of Kentucky began to clarify itself. It looked close rather than far, plain rather than ornate. It valued likeness, property, and stewardship. And it built the visual foundation for the next chapter—when towns would grow, tastes would expand, and materials themselves would become an expression of identity.

Wood, Clay, and Iron: Kentucky’s Material Imagination

Before oil paint dried on canvas or bronze cooled in molds, Kentucky shaped its artistic identity with raw materials—carved, fired, hammered, and joined by hand. Wood, clay, and iron were the native triad of expression. They built the state’s physical reality and shaped its aesthetic instincts. These were not auxiliary trades, nor mere ornamentation. They were the backbone of a regional visual language—functional, durable, and deeply expressive.

The Saltbox Chest and the Kentucky Long Rifle

Early Kentucky furniture was neither fashionable nor mass-produced. It was regional, born of necessity, made from local hardwoods—walnut, cherry, maple, and poplar. The forms were modest but intelligent. Clean lines, dovetail joints, hand-planed panels. Decoration, where it appeared, was restrained and geometric: a carved sunburst here, a scalloped apron there. These details were not indulgent—they were statements of care.

Among the most distinctive forms was the saltbox chest, so named for its sloped lid and simple, boxy construction. These chests stored everything from linens to meal to firearms. Some were painted with milk-based pigments—ochre, slate blue, dark green—and adorned with incised designs. A few show evidence of regional motifs: tulips, pinwheels, stylized birds. They sat flush against log walls, unmoved for generations.

Then there was the Kentucky long rifle—a functional weapon that, by the early 1800s, had become one of the most aesthetically sophisticated objects on the frontier. With its slender stock, extended barrel, and graceful lines, it was not only a hunting tool but an expression of precision and balance. Gunsmiths in Harrodsburg, Bardstown, and Boonesborough competed to outdo each other not just in firepower, but in design.

The stocks were typically made from curly maple and finished with linseed oil. Brass patch boxes were engraved with scrollwork, initials, or animal figures. Flintlock mechanisms were often imported from Pennsylvania or Virginia, but the final assembly and embellishment were local. Each rifle had its own weight, curvature, and personality. For many Kentuckians, it was their most prized possession—handed down like a grandfather’s name.

Three defining traits of the long rifle as an art object:

- Individuality: No two were exactly alike. Each bore the touch of its maker, often stamped or incised into the barrel.

- Ornament through function: Swirls and flourishes appeared only where structurally possible—on the patch box, the trigger guard, the comb.

- Endurance: These rifles outlasted their owners, often remaining in families for a century or more, both tool and heirloom.

Salt-Glazed Stoneware and Functional Ornament

Kentucky’s clay deposits, especially those in the Ohio River Valley, gave rise to a tradition of stoneware unmatched in its durability and visual economy. Potters in towns like Maysville, Russellville, and Louisville produced crocks, jugs, pitchers, and churns that met the daily needs of a growing population. But even these utilitarian forms became objects of beauty in skilled hands.

The process was elemental: coarse clay shaped by wheel or coil, dried in air, then fired in kilns lined with brick and fueled by wood. The salt-glazing process—where salt was thrown into the hot kiln to fuse with the silica in the clay—produced a glassy, slightly pitted surface. The color ranged from grey to blue to brown, depending on clay content and firing temperature.

Many of these vessels featured cobalt blue decoration—brushed on before firing in floral or abstract motifs. Some bore the potter’s stamp, others the owner’s initials or a simple numerical mark indicating volume. While unremarkable to modern eyes, these markings were vital in a time before mass labeling. A crock with “J.D. / Paris” scratched into its neck told you who made it and where.

In certain cases, the visual detail went further. Potters began adding small handles shaped like animal heads, or rims with feathered edges. Lids became domed and banded. A churn might have a row of incised circles just above the base—more gesture than necessity. These quiet flourishes speak to an enduring truth: when a man makes an object well, he finds a way to sign it, whether or not he writes his name.

Blacksmithing, Quilting, and the Art of Use

Ironwork in early Kentucky was not decorative in the European sense. No wrought-iron garden gates or ornamental scrolls graced the lanes. Instead, blacksmiths concentrated on the intersection of form and necessity: hinges, door latches, plowshares, nails, bits, stirrups. These objects, though humble, often carry a sharp elegance—lines smoothed by heat and struck by practiced hand.

Hinges forged in central Kentucky during the 1830s often had leaf-like terminals, a small curving detail that lifted them from mere utility. Fireplace tools were carefully weighted, their handles wrapped in iron ribbon. Branding irons, especially those used for horses or barrels, took on calligraphic qualities—each one a signature in fire.

The blacksmith was more than a tradesman. He was often the town’s most crucial artisan, its maker of keys and locks, its judge of weight and balance. His forge was a kind of studio, lit not by window but by flame.

And then there were quilts—arguably Kentucky’s most widespread and enduring form of visual art. Though made mostly by women (whose names were not always recorded), quilts were works of astonishing complexity and intention. They used locally available fabrics: wool, flax, cotton, and homespun linen. Patterns were passed from family to family—Log Cabin, Bear’s Paw, Double Wedding Ring—but each quilter adapted them. They stitched memory into pattern, using scraps from worn dresses, shirts, and aprons.

Kentucky quilts were rarely ostentatious. They favored muted colors, strong contrasts, and bold geometry. The artistry lay in rhythm and placement, in the tension between repetition and variation. Some were purely utilitarian. Others were made for dowries, births, or departures. A few were buried with the dead.

There are three clear reasons why these material forms endured as the backbone of Kentucky’s artistic tradition:

- They were made to be used, not displayed. The object had to work before it could please.

- They were rooted in place. Local materials shaped what could be made and how.

- They embodied memory. Objects were often handed down, signed, or dated—part of family identity.

In the decades to come, Kentucky would develop painters, sculptors, photographers. It would open galleries and university programs. But it never lost this foundational instinct: to make with the hands, to shape from what the land provided, and to find beauty in function. Art was not a separate pursuit—it was part of living well, working wisely, and leaving behind something that lasted.

Religious Imagery and the Rural Sublime

In Kentucky’s early visual tradition, religious art was neither grand nor overtly symbolic. It did not mimic European altarpieces or Gothic cathedrals. It emerged instead from plain buildings, hand-lettered signs, painted boards, and carved pulpits. The Protestant character of the region—especially Baptist and Methodist, with a smattering of Presbyterians and Shakers—meant that religious expression was more likely to be found in text than in image, in silence rather than spectacle. But when religious imagery did appear, it carried weight. It was sparse, direct, and often surprising in its force.

Baptist Meeting Houses and Symbolic Restraint

By the 1820s, Kentucky was dotted with rural churches—simple, often whitewashed structures built of timber or limestone. Most were unadorned. Their architecture reflected theological restraint: no stained glass, no painted ceilings, no gilded icons. Yet within these limits, a distinct visual language took root—one that found expression in proportion, placement, and material contrast.

The typical Baptist meeting house was a rectangular box with evenly spaced windows, a single central aisle, and an elevated pulpit. But the craftsmanship of these spaces often exceeded their austerity. Joinery was precise. Pulpits were hand-carved from local woods—cherry, walnut, or maple—and sometimes bore subtle moldings or symbolic motifs. A raised cross, a rosette, or a fluted column might appear, not to impress, but to suggest order and devotion.

In many churches, Scripture verses were painted directly onto interior walls or wooden tablets. These boards—usually painted black or dark blue—featured large block lettering in white or yellow. Common phrases included “FEAR GOD AND KEEP HIS COMMANDMENTS” or “BE YE DOERS OF THE WORD.” Their placement, usually behind the pulpit or above the entrance, established a clear relationship between word and space. The text became architecture.

While visual representation of sacred subjects was rare in Baptist and Methodist circles, it was not absent. Some meeting houses featured hand-painted symbols—open Bibles, anchors, doves—rendered with simplicity but care. These were not doctrinal arguments but visual reinforcements. The rural eye, trained on plows and fences, responded to clarity and purpose.

An especially poignant example survives in a Madison County chapel, where a hand-carved baptismal font bears the faint outline of a vine encircling the basin. The vine, unpainted and shallow, seems almost accidental—but it reflects a memory of scriptural metaphor: “I am the vine, ye are the branches.” Quietly, the object teaches.

Hand-painted Sermon Boards and Wall Texts

One of the most distinctive visual traditions in Kentucky’s early religious life was the painted sermon board. Used in both churches and revivals, these boards displayed the preacher’s chosen Scripture or hymn number. Most were made of pine or poplar, painted in dark colors with hand-lettered text. The brushwork varied—some were crude, others elegant—but the format remained consistent: centered text, capital letters, no flourish.

These boards were not considered art at the time, yet they reveal much about the region’s visual values. Their design prioritized legibility and permanence. The lettering was often modeled on printed Bibles, especially the King James Version. Serifs, spacing, and capital emphasis mimicked the look of sacred text in print. In an era before widespread literacy, the act of painting these words was itself a devotional labor.

Some families preserved old sermon boards as heirlooms. In Pulaski County, an 1831 board survives bearing the text: “WHAT DOTH THE LORD REQUIRE OF THEE?” Below it, in smaller letters: “Micah 6:8.” The paint has faded, but the composition remains: symmetrical, disciplined, unwavering. Such boards were often reused over years, the text repainted again and again, sometimes over the same surface—leaving a ghostly palimpsest of sermons past.

Wall texts served a similar function. In homes as well as churches, verses were sometimes stenciled directly onto plaster or wood-paneled walls. These verses, often framed in vines or decorative borders, created a kind of visual liturgy in domestic space. A dining room might bear “Give us this day our daily bread.” A bedroom, “Come unto me, all ye that labor.” These were not pious decorations; they were reminders, meant to be seen daily and lived into.

The Sacred Geography of Revival Grounds

Kentucky’s camp meeting tradition—especially during the Second Great Awakening—produced a form of religious imagery not tied to object or text, but to place. Revival grounds, often set in clearings or on hillsides, became temporary sites of intense religious emotion. Though ephemeral, they left a strong imprint on Kentucky’s visual consciousness.

These gatherings, sometimes numbering in the thousands, involved open-air preaching, hymn singing, and spontaneous expressions of belief. And though the structures were makeshift—wooden platforms, canvas tents, benches made from split logs—they were often arranged with symbolic intent. The pulpit was elevated. The singing area was central. The trees themselves became part of the architecture, framing the experience with light and shadow.

One Methodist account from 1802 describes a preacher mounting a stump, surrounded by a ring of torches, the night air filled with “wailing and trembling.” The scene reads like something out of Scripture, yet it occurred near Cane Ridge. It was not staged for beauty, but its power was undeniable. Firelight, trees, human voice—together, they formed a kind of sacred theater that no painting could match.

Some revival grounds developed into permanent camp meeting sites. These places, often marked by a simple arbor or brush arbor tabernacle, came to serve as visual memory. Even when unoccupied, they bore traces of their former use: rows of logs facing an empty platform, hymnbooks left in small wooden boxes, a hand-lettered sign nailed to a tree. In these spaces, religion was spatialized—made visible not in icons or gold, but in arrangement and memory.

Three recurring features of Kentucky’s religious imagery across these environments:

- Text as image: Sacred language became the dominant visual form, replacing figural or narrative representation.

- Restraint as meaning: Simplicity was not a lack of art but a statement of value—truth above decoration.

- Space as sacred: Whether in church, home, or clearing, arrangement carried theological weight.

Kentucky’s religious art did not seek to dazzle. It sought to endure. It gave form to belief not through painted saints or stained glass, but through carved pulpits, painted verses, and the layout of clearings in the woods. And in doing so, it shaped a visual tradition that still lingers—quiet, stern, and insistent.

Lexington and Louisville: Rival Hubs of Taste and Display

By the middle of the 19th century, Kentucky’s artistic life began to coalesce around two cities—Lexington and Louisville—each vying, in its own way, to become the state’s cultural capital. Lexington, with its landed gentry and thoroughbred aristocracy, cultivated a tradition rooted in refinement, private collections, and classical taste. Louisville, wealthier and more cosmopolitan, leaned toward public spectacle, urban display, and commercial innovation. The art scenes that emerged from these rival hubs were shaped not only by money, but by character: Lexington was discreet, patrician, and regional; Louisville was brash, modernizing, and open to national influence.

Classical Revivalism in Horse Country Estates

In the decades before the Civil War, Lexington was often called the “Athens of the West”—not merely for its academic institutions, but for its taste in art and architecture. Wealthy landowners, enriched by tobacco and horse breeding, imported styles from Philadelphia, Baltimore, and occasionally Europe. They built columned mansions in the Greek Revival style and filled them with portraiture, sculpture, and fine furniture—not in excess, but with studied intention.

The art favored in Lexington was emblematic of order and lineage. Oil portraits of family patriarchs, many painted by itinerant or visiting artists, hung in formal parlors. Landscapes depicting one’s estate, stable, or bloodstock pasture were commissioned not for aesthetic reflection, but as visual proof of standing. Classical motifs—urns, laurel wreaths, mythological scenes—crept into decorative work, especially in mantels, mirrors, and neoclassical busts. Marble was rare, but plaster casts of Roman figures circulated among the elite.

One of the most influential figures in this scene was Matthew Harris Jouett (1788–1827), a Lexington-born portrait painter who studied briefly under Gilbert Stuart and brought a polished Federal style to Kentucky society. Jouett painted governors, generals, and lawyers, capturing their likenesses with sharp, sober precision. His works, many still held in private collections and local museums, represent a rare blend of technical skill and regional identity—neither provincial nor overly ornate.

Jouett’s subjects often appear seated or standing against neutral backgrounds, framed by heavy drapery or modest classical columns. There is a stillness to his work, a measured dignity that matched the temperament of his clientele. Through Jouett and others like him, Lexington’s art scene defined itself not through innovation, but through refinement.

Three characteristic elements of Lexington’s mid-century visual culture:

- Formal symmetry: Both in architecture and painting, balance was prized. Portraits, houses, and even furniture designs favored centrality and proportion.

- Genealogical display: Art was not just for pleasure; it was evidence of family continuity and regional rootedness.

- Imported taste, local execution: While forms were often borrowed from the East Coast or Europe, the work itself was done by Kentuckians or those who came to Kentucky for commissions.

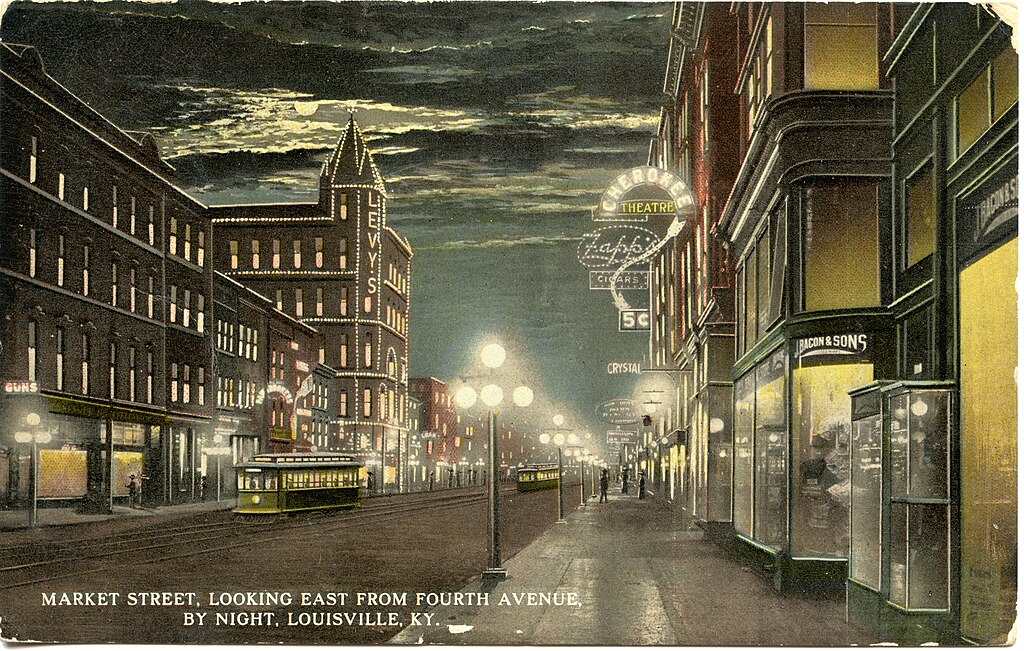

The Rise of Urban Galleries and Art Societies

Louisville, in contrast, was a city of commerce, river traffic, and constant influx. By the 1850s, it had become Kentucky’s largest city and a cultural melting pot. Its art scene developed along more public lines, shaped by exhibitions, print shops, photography studios, and eventually, commercial galleries.

Where Lexington cultivated private refinement, Louisville developed public display. Art societies—some loosely organized, others affiliated with schools or benevolent clubs—sponsored exhibitions of regional and visiting artists. These shows were often held in borrowed halls or reading rooms, and included a mix of oil paintings, engravings, watercolors, and decorative objects.

The Louisville Art Association, founded in the 1870s, was one of the earliest efforts to professionalize the city’s artistic class. It sponsored lectures, held juried exhibitions, and encouraged local artists to study abroad. Its membership included businessmen, educators, and a handful of trained painters, some of whom had studied in New York or Cincinnati before returning home. While its influence was modest by national standards, it marked a shift in Kentucky art—from domestic artifact to civic pursuit.

A key figure in Louisville’s early art community was Carl Christian Brenner (1838–1888), a German-born painter who immigrated to Louisville in the 1860s and became known for his romanticized landscapes of the surrounding countryside. Brenner’s work, while technically proficient, reflected a more sentimental, picturesque vision—one suited to urban tastes. His paintings of Cherokee Park, the Ohio River, and the Highlands neighborhood offered city dwellers a pastoral ideal, filtered through European eyes.

Louisville also played a pivotal role in the development of photography as art and documentation, particularly through the work of daguerreotypists and early portrait studios. These studios, often clustered near Main Street, catered to middle-class clients and emphasized clarity, accuracy, and poise. The image-as-proof—already a key feature in painting—translated seamlessly into the photographic medium.

Imported Prints and the Southern Grand Tour

Both Lexington and Louisville participated in the broader 19th-century trend of print collecting, though their preferences diverged. In Lexington, British mezzotints, American engravings of Revolutionary figures, and classical reproductions adorned the walls of homes and libraries. Louisville residents, by contrast, purchased prints of current events, city views, and theatrical scenes—images that reflected an urban orientation and a taste for novelty.

One curious Kentucky-specific variant of this collecting habit was the **“Southern Grand Tour”—**a kind of cultural pilgrimage undertaken by wealthier Kentuckians, especially before the war, to cities like Charleston, New Orleans, and occasionally Havana. Along the way, they acquired art: not always originals, but lithographs, miniatures, and ornamental objects from southern ateliers. These items made their way back into Kentucky parlors and halls, further expanding the visual vocabulary of the region.

Some merchants even began to import art directly from New York and Europe. By the late 1850s, at least two Louisville businesses were advertising framed prints, chromolithographs, and sculpture in shop windows—an early precursor to the modern gallery model. These businesses catered to a growing urban middle class that wanted more than furniture and mirrors: they wanted images that conferred sophistication.

In this period, Kentucky art began to look outward. Even as it retained its regional loyalties—its love of land, bloodlines, and restraint—it absorbed outside influence. Lexington reached for classical order. Louisville leaned into urban display. And between them, a complex, layered artistic culture took shape—one rooted in rivalry, but bound by shared geography and sensibility.

The Horse as Muse: Equine Painting and the Sporting Tradition

No other subject has captured Kentucky’s imagination—nor its image abroad—as completely as the horse. The thoroughbred, above all, became more than livestock or sport: it became a visual emblem of heritage, precision, and identity. In Kentucky, horses were not painted as background detail or rustic charm. They were central subjects, treated with the dignity and anatomical attention once reserved for kings and generals. This tradition of equine portraiture, born of pedigree and pride, gave rise to a uniquely regional form of art: exacting, noble, and saturated with meaning.

Lexington’s Stud Farms and the Visual Culture of Bloodlines

By the 1830s, Kentucky had already emerged as a national center for horse breeding, particularly around Lexington and the Bluegrass region, where limestone-rich soil made for strong-boned animals and ideal grazing. As breeding became both science and industry, so too did its visual representation. Owners wanted their most prized stallions and mares documented—not merely as animals, but as individuals with lineage and legacy.

Equine portraits were often commissioned at significant moments: a record-setting win, a first successful stud season, the sale of a champion colt. These paintings were typically done life-sized or nearly so, with the horse shown in profile, reins hanging, eyes alert, muscles taut. The goal was not to idealize but to commemorate, and to establish a visual record that could be passed down with the studbook.

The backgrounds varied. Some were painted with no setting at all, the horse suspended against a neutral field. Others included racetrack fences, rolling pasture, or the distinctive black plank fencing of Kentucky farms. A few incorporated grooms or handlers, though rarely as central figures. The focus remained firmly on the horse—its form, its markings, its stance.

These portraits were not mere trophies. They functioned as visual pedigrees—signaling breeding value, farm prestige, and market strength. When a Kentucky stallion was painted, the work often circulated as an engraving or lithograph, appearing in sporting journals, auction catalogues, and breeding pamphlets. The image became as valuable as the horse itself, extending its reputation beyond the fence line.

Three characteristics define this tradition:

- Accuracy over abstraction: Kentucky equine art emphasized conformation and color with near-scientific precision.

- Status embedded in form: Every detail—the tack, the sheen, the gate—was a signal of breeding discipline and stable wealth.

- Integration with commerce: Unlike most portraiture, these works moved beyond the private sphere into the marketplace.

Edward Troye and the Anatomy of Motion

No artist did more to establish the visual grammar of Kentucky horse painting than Edward Troye (1808–1874), a Swiss-born painter who spent the latter part of his life in Kentucky and whose work continues to define the genre. Troye was trained in Europe but came to the United States in the 1830s and quickly gained a reputation among Southern breeders and sportsmen for his ability to depict horses not just accurately, but meaningfully.

Troye’s paintings are marked by their calm intensity. His horses are usually shown in side profile, standing still, yet full of potential motion. Every tendon is visible. The hooves are precise. The flank is shaded to suggest depth, not sentiment. Troye resisted the temptation to dramatize or anthropomorphize. Instead, he offered a cool clarity—rooted in observation and respect.

One of his most famous paintings, Lexington (1857), depicts the famed stallion after his retirement from racing. The animal stands beside a groom in a lush paddock, the sky low and still. There is no embellishment. The power of the image lies in its restraint. Lexington’s muscles are rendered with clinical attention, his gaze distant but alert. The painting does not try to make the horse “heroic” in the classical sense—it simply shows him as he was, and that is enough.

Troye’s work was so trusted that breeders often used his portraits in lieu of photographs (which were still too crude for detailed animal documentation). His ability to capture not just a horse’s look but its bearing made him indispensable to the Kentucky bloodstock elite. He painted for the Alexanders of Woodburn Farm, the Shelbys, and other key players in the development of the American thoroughbred.

Troye’s legacy is more than artistic. He helped fix the image of the Kentucky horse in the national imagination—elegant, exact, and distinctly local. His portraits were circulated widely, engraved and reprinted, establishing a template that others would follow for decades.

Racing, Breeding, and the Composed Animal

As the racing industry matured in the second half of the 19th century, so too did its visual infrastructure. Kentucky tracks like Lexington Association Course and later Churchill Downs in Louisville became centers not just of sport, but of spectacle. Artists, photographers, and printmakers flocked to the races, documenting everything from crowd scenes to winning horses to painted banners and betting stubs.

But the horse remained the star—and remained, in art, largely composed and still. Action paintings were rare. The preferred image was one of poised readiness. Even after Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic motion studies revealed that horses in full gallop lifted all four legs off the ground, most equine painters in Kentucky stuck to tradition. They wanted a horse at rest, dignified, almost monumental.

This choice speaks to a broader cultural instinct: control over chaos. In Kentucky’s horse paintings, the animal is never wild. It is refined, trained, perfected through generations. Its power is latent, not explosive. Even racing scenes, when they appear, are tightly framed and symmetrical—suggesting order rather than frenzy.

Yet within that restraint, there is variation. Some portraits include subtle details that reveal the horse’s temperament—a cocked ear, a raised tail, a twist of the head. These small choices were deeply considered. Breeders often dictated such elements to the artist, ensuring that the image captured not just the look but the character of the animal.

By the early 20th century, photography began to replace painting as the primary medium of horse documentation. But the painted tradition did not disappear. It persisted in private commissions, in Kentucky clubs and farms, and in the iconography of the Kentucky Derby, which soon adopted equine imagery as its own form of civic branding. Even today, Derby posters and promotional art draw on the formal language established by Troye and his successors: clear lines, noble profiles, horses as emblems of control and beauty.

In Kentucky, the horse is not a metaphor. It is not an abstract ideal. It is a real, breathing, muscular presence—documented with care, rendered with discipline, and revered not just in barns and paddocks, but in oil, print, and pigment.

War and Aftermath: Visual Silence and the Postbellum Pause

The Civil War left a deep scar on Kentucky, not only in its fields and towns, but in its visual imagination. Though the state never officially seceded, it was riven by divided loyalties, neighbor against neighbor, family against family. The war brought with it not just death and destruction, but a prolonged quiet in the artistic life of the region—a suspension, a silence. The flourishing of portraiture, the energy of equine painting, the architectural embellishments of antebellum homes—all slowed or stopped. In their place came simpler forms, darker tones, and a more cautious relationship to memory.

Artistic Retrenchment in a Divided Landscape

Unlike other states where Union or Confederate identity was clearly defined, Kentucky’s ambiguous position—formally Union, informally split—created a kind of artistic paralysis. Artists no longer knew whom they were painting for, what subjects were safe, or how their work would be received. The result was a period of retreat, not just from politics, but from the ambitions of art itself.

Portrait commissions, once a staple of middle- and upper-class life, declined sharply. Many families either lacked the means or the desire to commission new works. Others had lost loved ones or homes and saw no reason to commemorate what had been fractured. Even artists who had made their name in the 1850s found themselves idle. Some moved north or west; others turned to illustration, carpentry, or teaching.

In this atmosphere, the very act of painting—especially anything that smacked of refinement or leisure—took on a precarious quality. It could seem vain, or politically fraught. The war had taught restraint in every field, and the visual arts were no exception. Subjects narrowed. Color palettes darkened. Expression turned inward.

One telling example is a series of anonymous mourning portraits from the 1870s found in a family archive near Danville. Rendered in graphite and ink on paper, these small, nearly monochrome images depict deceased sons, fathers, or husbands—uniformed, still, and often encased in oval frames or black drapery. These were not works of artistic ambition; they were acts of grief documentation, intensely private and devoid of flourish.

This period did not produce a grand artistic movement. Instead, it produced absence—a kind of visual stillness marked by hesitation, loss, and the practical necessity of rebuilding.

The Aesthetic of Survival: Minimalism by Necessity

Out of this silence, a new kind of visual culture emerged—pragmatic, reduced, but still meaningful. Artistic expression did not disappear; it relocated. It moved into gravestones, patchwork, carving, and domestic decoration—places where meaning could be communicated without risk, where expression could be folded into use.

Furniture from the postbellum period in Kentucky reflects this shift. Pieces became plainer, sturdier, with less interest in scrollwork or inlay. Shaker communities, especially those near Pleasant Hill, influenced this aesthetic of pared-down functionality. Clean lines, exposed joinery, and matte finishes replaced the gloss and decoration of earlier styles.

Painted signage—once vibrant and ornamental—also grew more austere. Farm signs, blacksmith advertisements, and general store placards employed block lettering, limited color schemes, and simple framing. In a culture where resources were scarce and ostentation discouraged, clarity replaced charm.

Even domestic arts such as quilting adapted. Quilts made in the decades after the war were often darker in tone, composed of repurposed cloth, and focused more on durability than display. Where earlier quilts might have celebrated marriage or family continuity, many now functioned as quiet tributes to loss—or as gifts marking the return of a surviving soldier. One 1873 quilt from Logan County, stitched in faded indigo and tobacco brown, carries initials embroidered into each square: brothers, cousins, and neighbors. Half bear a small cross beside the name.

This visual culture was not bleak, but it was stripped down. It favored:

- Monochrome over color, reflecting both material constraints and emotional restraint.

- Symmetry and repetition, offering order in a world that had seen chaos.

- Durability above all, in keeping with a society focused on rebuilding what could last.

The aesthetic was not invented. It was imposed by history—and accepted, even embraced, as a form of survival.

Memorial Art and Graveyard Carvings

One of the few artistic forms to truly flourish during this period was memorial carving. Cemeteries across Kentucky—especially those near Civil War battle routes—saw a proliferation of carved headstones, cenotaphs, and monuments. These were often the only sanctioned forms of public expression in a climate where politics were dangerous and taste was uncertain.

Local stonecutters created works of remarkable intensity. Limestone and sandstone markers bore deeply incised lettering, classical urns, weeping willows, lambs, and biblical references. Occasionally, an angel or clasped hands appeared—though most remained symbolic without becoming sentimental. Carving became a craft of deep quiet: the names of the dead chiseled into permanence, even as the country remained divided over how they had died.

In larger cemeteries, especially in Lexington and Louisville, grander memorials appeared: obelisk tombs, marble columns, and statues of soldiers—some Union, some Confederate. These monuments walked a careful line. They were tributes to sacrifice, not political declarations. Their inscriptions focused on “duty,” “honor,” “rest,” or “peace”—language designed to soothe, not to provoke.

One striking example stands in Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville: a life-sized stone soldier, head bowed, hands resting on a rifle’s barrel. The face is unmarked by expression, the uniform generic. It is not a portrait, but a symbol—meant to speak for thousands, without saying too much.

These visual choices were intentional. Kentucky, wary of reigniting tensions, crafted its memorial art to be universal in tone, even as it was local in origin. This form of public sculpture laid the groundwork for future civic art in the state: cautious, respectful, and bound by shared space.

The decades following the Civil War did not see an artistic boom in Kentucky. Instead, they saw a holding pattern—an art of humility, of labor, of staying intact. Where there was beauty, it was restrained. Where there was pride, it was quiet. And where there was grief, it was carved into stone, stitched into quilts, and painted in grays and browns.

Mountain Handcrafts and the Revival of American Artisanry

As industrialization swept through American cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, parts of eastern Kentucky stood still—geographically isolated, economically limited, and, in artistic terms, unusually intact. While urban centers turned toward factory-made goods, the Appalachian communities of Kentucky preserved a world of handmade objects, vernacular forms, and inherited skills. What was once merely survival craft—woodwork, weaving, pottery—began to be seen, increasingly, as art. And in the early 20th century, this Appalachian material culture, long ignored or patronized, became the object of national fascination and institutional support.

Berea College and the Ideals of Manual Labor

No institution played a more decisive role in shaping the trajectory of Kentucky mountain crafts than Berea College, founded in 1855 in Madison County. While Berea’s primary mission was educational and moral, it quickly became a center for craft revival, linking artistic tradition with social uplift and regional pride. Its emphasis on hand labor wasn’t ornamental; it was philosophical. Work with one’s hands was seen as dignified, necessary, and—if properly trained—beautiful.

By the 1890s, Berea had established workshops in furniture-making, weaving, and broomcraft. The design ethos was spare and honest: no scrollwork, no affectation, no copying of urban fashion. Instead, students and artisans produced sturdy ladder-back chairs, hand-loomed textiles, and plain chests with carefully joined edges. These items were sold throughout the region and, increasingly, to out-of-state buyers who saw in them something increasingly rare—authenticity in a mechanized world.

The Berea approach was neither nostalgic nor naive. Its founders saw in the Appalachian craft tradition a way to create self-sustaining communities—not museums of the past, but viable alternatives to factory dependency. Students learned not only to make but to teach, becoming emissaries of this handcraft culture to surrounding counties.

A few principles governed the college’s artistic philosophy:

- Function is beauty: No form was justified unless it served a use.

- Materials must be local: Cherry, hickory, oak, and wool from nearby farms—nothing imported.

- The hand is visible: Machine perfection was not the goal; small irregularities revealed the maker’s presence.

In a time when the decorative arts were increasingly commercialized, Berea kept a slower pace. It made no claim to innovation, but quietly built a canon of mountain artistry that still endures.

Weaving, Woodworking, and the Honest Object

Outside Berea, in homesteads across eastern Kentucky, the craft tradition had never stopped. Quilts, split-oak baskets, corn shuck brooms, and hand-carved bowls were made not as art objects, but as daily necessities. But as the 20th century dawned, attention turned toward these objects as examples of cultural value, even national identity.

Traveling reformers, writers, and collectors—some sincere, others condescending—descended upon the region, publishing articles and organizing exhibitions that celebrated the “pure American style” of Appalachian artisanship. While many of these narratives were romanticized, they nonetheless helped elevate Kentucky craft into the national conversation.

Particularly prized were:

- Textiles: Woven coverlets, rag rugs, and linsey-woolsey cloths dyed with walnut husks, goldenrod, or madder root.

- Woodenware: Trencher bowls, butter paddles, and handled mugs, shaped by drawknife and gouge, often finished with beeswax or tallow.

- Furniture: Especially the so-called “Appalachian armless rocker”—a low, sloped chair suited for weaving and kitchen work.

These objects were defined by proportion, restraint, and integrity of joinery. Ornament, when it appeared, took the form of a scalloped apron or a whittled finial—subtle flourishes rather than declarations.

It’s important to understand that the visual logic of mountain craft was not about minimalism, as it would later be interpreted, but about use and familiarity. An object looked the way it did because generations of use had taught what worked. A chair wasn’t “designed” in the modern sense—it was shaped over time by habit and correction. It was evolution by hand.

Many of these craftspeople—often anonymous, sometimes entire families—saw their work enter museums and galleries, often without names attached. But in the early 20th century, that began to change. A few makers, like James Still in Knott County, known for his finely turned bowls and chairs, began to gain recognition. Their work was sought not just as rustic curiosity, but as exemplary American form.

The Kentucky Guild of Artists and Craftsmen

In 1961, decades after Berea had laid the groundwork, a new institution emerged to formalize and expand Kentucky’s artisan tradition: The Kentucky Guild of Artists and Craftsmen, founded in Berea with the aim of uniting artists and craftspeople across the state. Unlike earlier efforts, which had focused narrowly on mountain traditions, the Guild welcomed a broader range of makers—ceramicists, textile artists, metalworkers, and more.

The Guild organized exhibitions, ran a permanent gallery space, and held the Kentucky Guild Fair, a twice-yearly outdoor event that remains one of the most respected craft festivals in the region. Importantly, the Guild insisted that traditional craft and contemporary art were not separate categories. A hand-woven shawl, a wheel-thrown mug, or a carved bench could hold artistic weight equal to painting or sculpture.

What distinguished the Guild’s approach was its refusal to treat craft as nostalgia. Many of its members were classically trained, even formally educated, but had chosen to work in materials and methods linked to earlier regional forms. They saw in Kentucky’s artistic inheritance a discipline worth continuing—not as imitation, but as vocabulary.

Among the notable Guild artists of the mid-20th century:

- Kenneth Thompson, a woodturner whose bowls and vessels emphasized grain, balance, and structural elegance.

- Marie Stewart, a weaver whose dye work and patterning drew on Shaker geometry and natural hues.

- Bill and Sally Mack, potters who built salt-fired kilns in the Appalachian foothills and revived older slip-glazing techniques.

The Guild’s greatest success may have been normalizing the idea of the working artist in rural Kentucky. No longer a marginal figure or a cultural outsider, the artist-craftsman became part of the region’s fabric—selling at fairs, teaching in schools, exhibiting in libraries and community centers.

By the 1970s, a full circle had been drawn: the same mountain forms once born of isolation and necessity were now, through persistence and adaptation, recognized as national art.

Midcentury Regionalists and the Kentucky Scene

The 1930s through the 1960s saw a quiet but lasting flowering of painting and illustration in Kentucky. While New York exploded with abstraction, and California flirted with surrealism, a number of Kentucky artists chose a different path. They remained tethered to place—not in resistance to modernism, but in confidence that regional observation could produce serious, enduring work. These artists were not hobbyists or nostalgic amateurs. They were trained, deliberate, and often deeply ambitious. Their subject was Kentucky: its rivers, porches, towns, hills, and human rituals.

Midcentury Kentucky regionalism fused painterly craft with documentary instinct. It gave attention to the ordinary and the overlooked. Its best practitioners turned familiar terrain into something luminous, not by dramatizing it, but by seeing it precisely. This period, though undercelebrated in national narratives, marks one of the richest chapters in the state’s visual history.

Paul Sawyier and the Licking River Vision

Though technically born in the 19th century, Paul Sawyier (1865–1917) came to define much of the aesthetic that Kentucky regionalists would carry forward. Trained in New York under William Merritt Chase, Sawyier returned to Kentucky and spent most of his life painting the banks, bridges, and streets of Frankfort, often by canoe. His watercolors and oils—at once soft and architecturally precise—created a visual language for small-town Kentucky that later artists would inherit.

Sawyier painted quiet things: the curve of a river at dusk, the shadow of a sycamore on water, a steamboat moored at rest. His palette was restrained, his brushwork loose but controlled. What gave his work gravity was not its technical flair, but its sense of being there—of understanding a place not through impression but through return. He painted the same docks, creeks, and buildings again and again, never tiring of their changing light.

Though he died in relative obscurity, Sawyier’s work was rediscovered in the 1930s and ’40s, thanks in part to exhibitions at the Kentucky State Capitol and the growth of interest in American regional art. His images—particularly of the Licking River, Elkhorn Creek, and the surrounding countryside—became touchstones for artists who rejected the anonymity of abstraction and the agitprop of social realism.

Three elements define Sawyier’s enduring influence:

- Geographic fidelity: He painted where he lived, never mythologizing or relocating his subject.

- Formal modesty: His compositions were spare but balanced—sympathetic to the quietness of the region.

- Emotional reserve: Sawyier’s paintings do not announce emotion; they invite stillness, waiting to be entered.

Realism, Patriotism, and the American Vernacular

In the 1930s, federal initiatives such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Federal Art Project (FAP) brought an influx of funding and direction to local artists, especially those willing to depict American life in accessible, representational forms. Kentucky, with its strong narrative tradition and social conservatism, proved fertile ground for this style.

Painters like Victor O. Schreckengost, Clifford Amyx, and Eleanor Dickinson produced murals, etchings, and illustrations that emphasized work, place, and continuity. Subjects included tobacco fields, courthouse squares, coal towns, train yards, and schoolrooms. These images were not polemical or utopian. They documented what was there—and did so with seriousness.

One striking WPA mural still visible in a Kentucky post office shows a man harvesting burley tobacco beneath a late-season sky, his shirt damp, the leaves broad and curled. There is no irony in the image, no critique of labor. It presents rural life as worthy of monumental scale, not in sentiment, but in dignity.

This regional realism was not nostalgic. It did not pretend the past was simpler, nor the land unspoiled. Rather, it assumed that American life could be looked at directly, without pretense or disfigurement. Kentucky artists working in this mode used their own families, neighbors, and barns as reference—believing that observation could be a moral act.

WPA Projects and Rural Documentation

The WPA and related federal programs had a particularly significant visual legacy in Kentucky: they funded thousands of documentary photographs, dozens of murals, and hundreds of works on paper. While many of these have been lost, others remain in county buildings, libraries, and regional archives.

In addition to visual artists, the WPA employed craft documentarians, who photographed and catalogued handwoven coverlets, baskets, musical instruments, and domestic interiors across Appalachia. These images, while intended for anthropological record, possess a quiet formal beauty—compositionally careful, light-sensitive, and often more revealing than the artists realized.

Among the most notable WPA-affiliated figures was Harlan Hubbard, though he worked somewhat outside official programs. Hubbard (1900–1988) was a painter, writer, and craftsman who, with his wife Anna, built a life of deliberate isolation along the Ohio River, near Payne Hollow. His paintings and woodcuts—often depicting river scenes, homestead labor, or solitary barns—carried a Thoreauvian calm. Unlike the forced optimism of some WPA art, Hubbard’s work was austere and exacting.

Kentucky’s WPA-era visual culture can be summarized not as a style but as a gesture of regard. It gave visual form to local life without caricature, and it elevated common rhythms—plowing, quilting, walking to church—into public memory.

Some defining traits of this rural documentation include:

- Unsentimental framing: Subjects were rarely romanticized. A mine entrance, a hillside shack, a group of schoolchildren—they were shown without decoration.

- Narrative impulse: These images often told implied stories—not symbolic, but sequential.

- Evidence of continuity: The past was not contrasted with the present but shown flowing into it.

By midcentury, Kentucky had developed a mature, regionally anchored artistic voice. It did not chase trends, nor did it apologize for its restraint. Whether in watercolor, woodcut, or mural, the best of this period expressed confidence in place—quietly asserting that the local, when seen clearly and rendered with care, could reach beyond itself.

Craft, Clay, and the Studio Movement

By the 1960s and ’70s, Kentucky entered a new phase in its visual history—neither purely regionalist nor wholly modernist. Across the state, artists began turning toward craft as fine art, embracing materials long considered “utilitarian” and placing them in the realm of sculpture, installation, and gallery exhibition. This shift did not abandon Kentucky’s long-standing respect for handwork. Instead, it amplified it—bringing clay, wood, fiber, and metal into the studio with renewed seriousness, technical refinement, and, increasingly, conceptual depth.

Kentucky’s longstanding tradition of craftsmanship, shaped by its agrarian past and mountain isolation, proved fertile ground for the rise of the American Studio Craft Movement. But what distinguished Kentucky’s interpretation was its continued insistence on discipline over theory, form over gesture, and material intelligence over manifesto. The studio movement here did not seek novelty for its own sake. It sought to elevate what had already been there—kilns, looms, benches, and wheels—into fully articulated artistic language.

The Rise of Ceramics and Furniture as Fine Art

Of all the disciplines reshaped during this period, ceramics took the most visible leap. Clay had long been present in Kentucky’s artistic vocabulary—first as stoneware, then as Appalachian pottery—but in the 20th century it evolved into a studio-based practice, tied to form, experimentation, and aesthetic ambition.

Much of this development can be traced to university-based programs, especially at the University of Kentucky, Western Kentucky University, and Berea College, where artist-educators began to build serious curricula in ceramics, sculpture, and woodworking. These programs brought kilns, glazes, throwing wheels, and kilning techniques into structured dialogue with the broader art world.

Prominent among these educators was Walter Hyleck, who helped establish the ceramics program at Berea College and taught generations of students to think of pottery not just as craft, but as expressive form. Hyleck’s own work balanced function and abstraction—often vessel-based, but subtly distorted, carved, or surface-treated to challenge the eye. His ceramics felt ancient and modern at once.

Another pivotal figure was Wayne Ferguson, a sculptor and potter based in Paducah, whose large-scale stoneware pieces combined thrown and hand-built elements. Ferguson’s work, rooted in traditional forms, often featured ash glazes, incised motifs, and surfaces that seemed almost geological in character—earth responding to fire.

Meanwhile, the woodworking tradition, always strong in Kentucky, gained new attention through artists like Charles Counts and David Dike, who took the techniques of Appalachian furniture-making and began abstracting their forms. Rockers became sculpture. Joinery became pattern. Traditional pieces were stripped down to their skeletal logic—inviting the viewer to see construction as composition.

Three shifts characterized the studio craft movement in Kentucky:

- Function was retained, then reimagined: Many artists began with usable forms—cups, bowls, chairs—but pushed them into new aesthetic territory.

- Surface became expressive: Glazes, textures, burns, and tool marks were no longer mistakes to hide, but effects to celebrate.

- Scale expanded: What was once domestic became architectural—ceramic walls, furniture installations, monumental vessels.

John Tuska and the Figure Reimagined

Perhaps the most widely recognized figure in Kentucky’s late 20th-century art scene was John Regis Tuska (1931–1998), a sculptor and draftsman who taught at the University of Kentucky and left behind one of the state’s most provocative and technically virtuosic bodies of work.

Tuska worked across media—ceramics, bronze, fiber, and drawing—but remained fixated on a single subject: the human figure, often contorted, fragmented, or bound. His work combined anatomical realism with psychological tension. Figures emerged from clay as if dug from ruins—scarred, blindfolded, straining toward form. He used molds, plaster casts, and built-up slabs, often leaving seams and handprints visible, as if refusing to let the object forget its making.

In his later work, Tuska created a series of installations that included clay-pressed books, chairs, and garments, each piece bearing the imprint of a living body. These were not symbolic gestures; they were literal acts of preservation—art as archaeology of the present.

Though Tuska was deeply involved in the national sculpture scene, he remained committed to Kentucky, mentoring students, exhibiting locally, and eventually establishing the Tuska Center for Contemporary Art in Lexington. His influence continues to ripple outward, especially among younger artists working in mixed media and narrative form.

What makes Tuska’s role distinctive is that he brought intensity to materials without pretension. He believed in the weight of things: in clay, in effort, in physical trace. His work could be harrowing, but it never lost its grounding in craft. He treated the figure as a site of truth—mortal, vulnerable, but unavoidably real.

Kilns, Studios, and Clay Communities

Throughout the late 20th century, ceramicists across Kentucky began organizing workshops, cooperatives, and studio collectives. These were not avant-garde salons, but working communities, where kilns were shared, wood was chopped, and glaze recipes were passed from hand to hand. The resulting network formed a kind of silent infrastructure beneath the state’s more visible art institutions.

One such hub was the Kentucky Mudworks community, founded in the early 2000s but built on decades of collaborative tradition. Others included studio enclaves near Berea, Lexington, and Paducah, where potters gathered for weekend firings and exhibitions, often drawing collectors from across the Midwest.

Many of these communities operated around wood-fired or salt-glazed kilns, preserving the elemental character of early stoneware. Artists reveled in the unpredictability of flame: color shifts, ash deposits, warping, and glaze drips that no electric kiln could replicate. This return to elemental technique did not reflect anti-modernism, but rather a conscious choice to embrace process and risk.

At annual sales and fairs, buyers learned to see the differences between slip and shino, between pulled handles and coiled lips. The public, long accustomed to slick imported ware, began to recognize the value of weight, texture, and imperfection. The result was a culture that valued the tactile over the theoretical—art meant to be used, held, even worn down with time.

By the turn of the millennium, Kentucky’s studio movement had accomplished what few regions had: it had sustained a craft tradition that was neither nostalgic nor diluted, producing work of national caliber while remaining rooted in place.

Academic Institutions and the Anchoring of Art Education

As Kentucky’s studio and regional art traditions matured in the 20th century, their durability increasingly relied on institutions—colleges, universities, art centers, and local schools—that provided both formal training and infrastructural support. What had once been taught informally, from master to apprentice or from parent to child, now entered syllabi, exhibitions, and accreditation systems. This was not a bureaucratization of creativity, but a reinforcement: a deepening of skill through continuity, rather than rupture.

Academic institutions across Kentucky did not impose coastal or European styles on local students. Instead, many became platforms for sustaining and refining regional forms. They offered tools, theory, and critical frameworks—but without breaking the connection to material, land, and place. This balance between academic rigor and regional loyalty became a defining feature of Kentucky’s mid-to-late-century visual culture.

University of Kentucky’s Art Department and Its Influence

Among all institutions in the state, the University of Kentucky (UK) in Lexington played the most significant role in shaping professional art practice. By the mid-20th century, UK had assembled a serious and eclectic art faculty, including painters, sculptors, printmakers, and ceramicists whose work bridged tradition and experimentation. These were not academic ideologues; they were practicing artists who saw teaching as both vocation and obligation.

As mentioned earlier, John Tuska became one of the program’s most celebrated figures. But he was not alone. Faculty such as James Robert Foose (printmaking and drawing) and Robert May (painting) built strong disciplines around observational rigor and technical development. These instructors emphasized craftsmanship, anatomy, and composition, but allowed space for personal expression—provided it was grounded in skill.

UK’s art department also pioneered a number of community outreach initiatives, bringing exhibitions to rural schools, offering public lectures, and creating programs for veterans and working adults. The aim was not merely to train professionals, but to establish art as a civic good, available and visible to all.

Equally important was UK’s role in curating and preserving Kentucky art history. Through the University of Kentucky Art Museum, founded in 1976, the institution developed a permanent collection that included not only national works but a substantial and serious representation of regional artists—from 19th-century portraitists to contemporary craft practitioners. This museum, while modest in scale, helped cement the legitimacy of Kentucky’s own traditions within a broader art historical context.

By the late 20th century, UK had become a magnet for young artists across Appalachia and the Bluegrass who wanted training without cultural severance—a place where one could learn bronze casting or mixed-media installation without abandoning drawing, wheel-thrown pottery, or oil portraiture.

Art Centers, Workshops, and the Shape of Local Training

While universities laid the groundwork for formal instruction, a network of community art centers, workshops, and summer programs extended artistic access far beyond academic campuses. These institutions rarely made headlines, but their cumulative effect was profound: they nurtured young talent, offered continuing education to adults, and built a cultural infrastructure that reached from county seat to coal camp.

The Kentucky Arts Council, established in 1966, became a coordinating force in this movement—offering grants, curating exhibitions, and sponsoring artist residencies across the state. But the real energy came from smaller venues:

- The Living Arts and Science Center in Lexington, founded in 1968, blended art education with hands-on experimentation, especially for children and underserved youth.

- The Louisville Visual Art Association, with roots in the 1909-founded Art Center Association, developed one of the state’s longest-running art outreach programs, including the Children’s Fine Art Classes that identified and supported talented students regardless of background.

- The Paducah School of Art and Design, part of West Kentucky Community and Technical College, offered intensive instruction in ceramics, drawing, and metalwork—again reflecting the state’s commitment to material literacy over conceptual posturing.

Workshops also flourished during this period, especially in connection with craft fairs, guild meetings, and regional festivals. It was not unusual for a child to study watercolor in a courthouse basement, or for a retired coal miner to take up woodcarving through a community program funded by the state. Art had ceased to be remote. It had become participatory—woven into the social life of the region.

The pedagogical emphasis across these centers was consistent: mastery of material first, ideas second. Even in abstract or experimental modes, Kentucky artists were expected to understand form, weight, and structure. There was little tolerance for theory unmoored from skill.

Patronage, Prizes, and Professionalization

No artistic culture can sustain itself without recognition, and throughout the late 20th century, Kentucky developed a system—imperfect but growing—that supported artists with prizes, commissions, and patronage.

Early on, much of this support came from civic organizations, church groups, and local banks, which sponsored annual art shows, often tied to county fairs or seasonal festivals. These events, while modest, offered artists cash prizes, public exposure, and community support. In time, larger institutions joined in: the Governor’s Awards in the Arts, the Al Smith Individual Artist Fellowships, and juried exhibitions hosted by state museums and arts councils.

One of the more quietly influential mechanisms was corporate collecting, especially by regional banks and law firms. Beginning in the 1980s, firms such as Central Bank in Lexington and Brown-Forman in Louisville began acquiring works by Kentucky painters, printmakers, and ceramicists—not as speculative investments, but as serious cultural assets. These collections often emphasized landscape, still life, and figurative work—styles that reflected the state’s ongoing visual values of clarity, legibility, and rootedness.

Additionally, artists benefited from public commissions for courthouses, hospitals, and universities. These were not grand or flashy works. They were quiet, site-specific, and often material-intensive: bronze plaques, ceramic murals, woven panels—pieces that engaged their surroundings without dominating them.

As a result, by the early 2000s, Kentucky had achieved something rare: a network of working artists—not celebrities or bohemians, but makers who lived from their work, taught locally, and remained within the region. They had students. They had collectors. They had studios. And they had the means to pass it on.

Collectors, Auctions, and the Quiet Value of Place

The value of Kentucky art has never been measured entirely in dollars; it has always included the price of memory, place, and a private judgment about what ought to be kept. Yet alongside quilts, chairs, and horse portraits there developed, slowly and then with more confidence, a regional market: private collectors, town auction houses, estate sales, and a small but persistent group of institutional buyers who decided that local work deserved to be conserved, catalogued, and sometimes, traded. This economy never became frenzied; its rhythms are those of county courthouses, framed parlor walls, and deliberate purchases made with both taste and thrift.

The Quiet Collector: Motives and Habits

Collectors in Kentucky are often not what one pictures in metropolitan narratives—rarely celebrities, more commonly lawyers, physicians, business owners, and retired farmers. Their motives tend to be practical and clear: a painting to hang over a mantel, a set of chairs to fill a dining room, a chest to hold linens and family papers. Many collect out of affection for a maker whose name they know—an apprenticeship remembered, a beloved teacher, a local potter whose wares they used daily. Others buy because a piece “fits” the house, the light, the porch—the way the object completes a life already arranged.

There are three patterns that repeat among these steady buyers:

- Preference for objects that show use and repair, not perfection.

- A tendency to favor makers with a clear regional tie—a pot stamped with town initials, a chair with a familiar joinery.

- Reluctance to follow national fashion; tastes are formed by family rooms, not magazines.

Micro-narrative: at an estate sale in a small central-Kentucky town, an elderly man outbid three out-of-state dealers for a cedar chest only slightly fingered at the corners. He paid more than he intended and walked it home through dusk, the chest balanced on the back of his truck like a small plinth. For him, the purchase was less about investment than about restoration: a housemate’s grandmother had once owned a similar chest, and the new object would return an old sightline to the family home.

Collectors who become visible—those who donate to a university museum or underwrite a local gallery—do so for reasons of legacy as much as philanthropy. The impulse is to create anchors: a named acquisition fund, a donated portrait of a community leader, a sponsored exhibition of ceramics. These acts of patronage bind private taste to public memory and ensure that regional work is preserved where it can be studied.

Auction Rooms, Estate Sales, and the Mechanics of Local Markets

Kentucky’s market for art and antiques operates on multiple scales. At the grassroots end are estate sales and county auction rooms—places where furniture, folk paintings, quilts, and stoneware change hands among neighbors. These are intimate encounters: buyers inspect dovetailing, judges of joinery nod to one another, and prices are set as much by local knowledge as by supply and demand.

A rung up, regional auction houses handle larger lots—collections from long-standing families, entire contents of a country house, or the estate of a retired collector. Here the pace quickens; catalogs are printed, short biographies included, provenance is described (often conservatively), and objects travel beyond the county lines. Yet even these auctions rarely become national spectacles. Most lots sell to regional buyers, museums in neighboring states, or dealers who trade in Americana.

At the top end, a small number of metropolitan dealers and collectors come to Kentucky for specific searches: a Paul Sawyier watercolor, a Matthew Harris Jouett portrait, an Edward Troye equine study. When such works appear—often through inheritance or discovery—they attract attention beyond the state. But these are exceptions, not the rule. More commonly, value is made locally: a quilt bought for a hundred dollars at a church fair will, decades later, be appraised and acquired by a university collection for preservation.

Three practical facts that sustain the market:

- Documentation matters: signed works, maker’s stamps, and family provenance increase a piece’s stability of value.

- Condition is a moral and economic measure; honest repairs are acceptable; concealment is not.

- Local exhibitions and repeat sales create a feedback loop that educates buyers and stabilizes prices.