Italy’s art history is nothing short of extraordinary. As the birthplace of the Roman Empire, the cradle of the Renaissance, and a hub for avant-garde experimentation, Italy has profoundly shaped Western art and culture. For centuries, artists, architects, and thinkers from across Europe and beyond have looked to Italy for inspiration, drawn by its masterworks, its deep connections to antiquity, and its enduring emphasis on beauty, harmony, and human creativity.

From the grandeur of ancient Roman monuments to the bold innovations of Futurism, Italian art has been both a mirror of its time and a beacon for future generations. Its legacy encompasses a breathtaking array of achievements, from Michelangelo’s David to the stunning mosaics of Ravenna, from the frescoes of Giotto to the modern abstractions of Lucio Fontana. Whether shaped by religion, politics, or individual genius, Italian art reflects the richness of its cultural heritage and the dynamism of its people.

Why Italy? A Legacy Rooted in History

Italy’s unique geography and historical significance made it a cultural crossroads for millennia. As the center of the Roman Empire, Italy was home to artistic and architectural achievements that laid the foundation for Western art. The legacy of ancient Rome—its emphasis on realism, its mastery of perspective, and its monumental public works—continued to influence Italian art long after the empire’s fall.

During the Middle Ages, Italy became a hub of innovation in religious art, as the Christian church fostered artistic development to glorify God and inspire devotion. The Renaissance, born in Florence and spreading throughout Europe, marked a pinnacle of Italian creativity, blending classical ideals with groundbreaking techniques in painting, sculpture, and architecture. Even in the 20th century, Italy remained a cultural leader, with movements like Futurism challenging conventions and shaping modern art.

Themes That Define Italian Art

Across the centuries, certain themes and values have consistently shaped Italian art:

- Humanism and the Celebration of the Individual: From the Renaissance onwards, Italian artists have explored the beauty and complexity of the human form, often celebrating individual achievement and expression.

- Nature and the Divine: Whether through the harmonious landscapes of Renaissance frescoes or the celestial mosaics of early Christian churches, Italian art often reflects a profound connection to nature and spirituality.

- Innovation and Experimentation: Italian artists have consistently pushed boundaries, introducing techniques like linear perspective during the Renaissance or kinetic movement in the Futurist era.

- National and Regional Identity: Italy’s art reflects its diverse regions, from the classical grandeur of Rome to the Venetian mastery of color, the Tuscan embrace of harmony, and the Neapolitan flair for drama.

A Journey Through Italy’s Artistic Legacy

This series will take you through the major chapters of Italian art history, highlighting the masterpieces, movements, and figures that have defined each era. We will explore:

- The monumental achievements of ancient Roman art and architecture.

- The rise of Christian and Byzantine art in medieval Italy.

- The architectural and artistic marvels of the Romanesque and Gothic periods.

- The revolutionary spirit of the Italian Renaissance.

- The grandeur of Baroque and the elegance of Rococo.

- The political and cultural shifts of Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

- Italy’s contributions to modern and contemporary art, from Futurism to Arte Povera.

Each chapter will uncover how Italian art has evolved alongside the nation’s rich and complex history, offering insights into its enduring power to inspire and transform.

Italy: The Eternal Source of Inspiration

Italy’s artistic heritage is not just a reflection of its past; it is a living tradition that continues to shape the world of art and culture. Whether visiting the frescoes of Assisi, marveling at the works of Caravaggio, or encountering contemporary installations in a Roman gallery, one cannot help but feel the vibrancy of Italy’s artistic spirit.

In the chapters ahead, we will delve into the wonders of Italian art, exploring how this remarkable nation has shaped our understanding of beauty, creativity, and human potential. From ancient to modern, the story of Italian art is a testament to the power of imagination and the enduring legacy of a people who have truly made art their own.

Chapter 1: Ancient Roman Art (509 BCE–476 CE)

The art of ancient Rome stands as a cornerstone of Western culture, blending Greek ideals with Roman ingenuity to create a legacy that continues to inspire. As the Roman Republic transitioned to the Roman Empire, art became a powerful tool for celebrating military triumphs, asserting political authority, and glorifying the achievements of Rome. Through sculpture, architecture, mosaics, and frescoes, Roman artists developed a distinct style that balanced realism with grandeur, setting the stage for centuries of artistic innovation.

The Influence of Greek Art

Roman art was heavily influenced by the Greeks, whose colonies in southern Italy introduced classical forms and techniques to Roman artists. The Romans admired Greek art for its beauty and craftsmanship, and as they expanded their empire, they brought home countless Greek statues, vases, and architectural ideas. However, Roman art was not merely imitative—it adapted and evolved, emphasizing realism, practicality, and narrative.

- Adaptation of Greek Sculpture: While Greek sculpture idealized the human form, Roman artists sought greater realism, capturing individuality and personality in their portraits. Roman busts and statues, such as the Augustus of Prima Porta (c. 20 BCE), exemplify this blend of idealism and realism, portraying subjects with both physical perfection and unique characteristics.

- Mythology and Public Imagery: Like the Greeks, Romans frequently depicted gods and mythological scenes in their art, but they also celebrated historical events and public figures, emphasizing the grandeur and power of the Roman state.

Architecture: Engineering and Grandeur

Roman architecture is one of the most enduring aspects of their artistic legacy, characterized by monumental structures that combined beauty with practicality. Roman architects innovated with materials like concrete, allowing for the creation of large-scale buildings and complex designs that were previously impossible.

- The Colosseum: Completed in 80 CE, the Colosseum remains one of the most iconic Roman structures. This massive amphitheater, capable of seating up to 50,000 spectators, hosted gladiatorial games and public spectacles, reflecting the Romans’ love for entertainment and their engineering prowess.

- The Pantheon: Constructed during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (118–128 CE), the Pantheon is a masterpiece of Roman engineering and design. Its massive dome, with an oculus at the center, demonstrates the Romans’ mastery of concrete and their ability to create harmonious, awe-inspiring spaces.

- Aqueducts and Infrastructure: Roman art extended into public works, such as aqueducts, roads, and bridges, which were both functional and aesthetically pleasing. The Pont du Gard in France exemplifies how Roman engineering combined utility with beauty, using elegant arches to transport water over great distances.

Mosaics and Frescoes: Everyday Life and Mythology

Roman homes and public buildings were often adorned with intricate mosaics and frescoes, showcasing both mythological themes and scenes from everyday life. These works were not only decorative but also served to communicate social status and cultural values.

- Pompeii and Herculaneum: The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE preserved the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, offering a remarkable glimpse into Roman art and daily life. Frescoes from Pompeii, such as those in the Villa of the Mysteries, depict detailed scenes of religious rituals, mythology, and domestic life, using vibrant colors and dynamic compositions.

- Mosaic Art: Roman mosaics often adorned floors and walls, featuring intricate patterns, mythological figures, and natural scenes. The Alexander Mosaic (c. 100 BCE), discovered in Pompeii, depicts the Battle of Issus with extraordinary detail and dramatic intensity, showcasing the skill of Roman mosaicists.

Portraiture and Realism

Roman portraiture stands out for its focus on realism, capturing the individuality and character of its subjects. Unlike Greek idealism, Roman portraits often emphasized age, wisdom, and experience, reflecting societal values that honored maturity and public service.

- Veristic Portraiture: During the Republican period, Roman portraiture favored a style known as verism, which emphasized realistic, even exaggerated, depictions of age and imperfection. Busts of Roman senators, for example, highlight wrinkles and other features that signified wisdom and virtue.

- Imperial Portraits: With the rise of the empire, portraiture became a tool for political propaganda. Emperors like Augustus and Trajan commissioned statues and coins that depicted them as strong, youthful, and divine, reinforcing their authority and legacy.

Historical Reliefs and Narratives

Roman artists excelled at using relief sculpture to depict historical events and achievements, often decorating public monuments with detailed scenes of military victories and civic accomplishments.

- The Ara Pacis: The Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), completed in 9 BCE, celebrates the reign of Emperor Augustus and the establishment of peace throughout the empire. Its intricate reliefs depict allegorical and historical scenes, blending realism with symbolic imagery.

- Trajan’s Column: Built in 113 CE, Trajan’s Column commemorates Emperor Trajan’s victory in the Dacian Wars. The column’s spiral reliefs tell a continuous story of the campaign, illustrating battles, engineering feats, and the emperor’s leadership. This innovative narrative approach influenced the development of Western art for centuries.

Themes of Power, Legacy, and the Divine

Roman art consistently emphasized themes of power, legacy, and the divine, reflecting the empire’s ambition and its rulers’ desire to be remembered. Whether through monumental architecture, realistic portraiture, or mythological scenes, Roman art conveyed the grandeur of the state and the permanence of its achievements.

- Propaganda and Authority: Art was a tool of propaganda, used to legitimize the rule of emperors and reinforce the ideals of Roman civilization.

- Eternal Rome: The concept of Rome as an eternal city was central to its art, with works designed to endure and inspire future generations.

The Legacy of Roman Art

The artistic achievements of ancient Rome laid the foundation for Western art and architecture. Roman innovations in engineering, realism, and narrative continue to influence modern art, from Renaissance revivals of classical ideals to contemporary architectural designs inspired by Roman forms. The survival of Roman monuments and artworks serves as a testament to the enduring power of their creativity, reminding us of their pivotal role in shaping the visual culture of the Western world.

Chapter 2: Early Christian and Byzantine Art in Italy (300–900 CE)

The early Christian and Byzantine periods in Italy marked a profound transformation in art and culture, as the Roman Empire adopted Christianity and shifted its capital to Constantinople. This era saw the emergence of new artistic styles and symbols that reflected the spiritual and theological focus of the Christian faith. Churches replaced temples as centers of artistic expression, and mosaics, frescoes, and sculptures took on sacred significance, emphasizing divine transcendence and the promise of salvation. Italy, as the bridge between the Western Roman Empire and the Byzantine East, played a pivotal role in shaping this artistic evolution.

The Rise of Early Christian Art

The legalization of Christianity under Emperor Constantine in 313 CE (with the Edict of Milan) ushered in a new era of art, as Christians could openly express their faith. Early Christian art, which had previously developed in secret, began to flourish, with a focus on symbolic imagery and biblical narratives.

- Catacomb Art: Before Christianity was legalized, early Christian art often appeared in the catacombs of Rome, where Christians buried their dead and gathered for worship. These frescoes and carvings featured symbolic motifs such as the fish (Ichthys), the Good Shepherd, and the anchor, representing hope and salvation.

- Constantinian Basilicas: With Constantine’s patronage, monumental basilicas were constructed as places of worship, such as the Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (completed in the 4th century). These structures featured large interiors to accommodate congregations, a stark contrast to the smaller, private worship spaces of earlier periods.

The Flourishing of Mosaics

Mosaics became the dominant art form of the Byzantine and early Christian periods, adorning church walls, apses, and ceilings with shimmering, colorful tesserae that depicted biblical scenes and theological concepts. Italy’s churches and basilicas became showcases for this stunning art form, blending Eastern and Western influences.

- Ravenna: A Mosaic Masterpiece: The city of Ravenna, a major center of Byzantine influence in Italy, is home to some of the most exquisite mosaics of the era. Key sites include:

- The Basilica of San Vitale (6th century): Famous for its intricate mosaics of Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora, surrounded by attendants, these works symbolize the union of church and state under Byzantine rule.

- The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (5th century): Its mosaics, such as the Good Shepherd and starry sky ceilings, blend naturalistic details with symbolic imagery, reflecting the transition from classical art to a more spiritual focus.

- Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome: Built in the 5th century, this basilica features mosaics depicting Old Testament scenes, blending Roman stylistic traditions with early Christian iconography.

Mosaics became a visual language of faith, their glittering surfaces symbolizing the divine light of heaven and the eternal presence of God.

Byzantine Influence and Iconography

The Byzantine Empire’s influence on Italian art was profound, particularly in regions like Ravenna and Venice, which maintained close ties to Constantinople. Byzantine art introduced a more abstract and spiritual aesthetic, emphasizing otherworldly beauty and divine majesty.

- Gold and Symbolism: Byzantine mosaics often used gold backgrounds to create a sense of divine space, separating the sacred from the earthly. Figures were depicted in frontal, formal poses, with elongated proportions and solemn expressions, emphasizing their spiritual rather than physical presence.

- Icons and Devotional Art: Iconography became central to Byzantine-inspired Christian art, with images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints serving as objects of veneration and tools for prayer.

This stylistic shift from naturalism to abstraction reflected a theological emphasis on the divine and eternal, moving away from the human-centered focus of classical art.

Architecture and Sacred Space

Early Christian and Byzantine architecture in Italy transformed the Roman basilica into a Christian place of worship, combining functionality with spiritual symbolism. Churches were designed to inspire awe and reverence, guiding the faithful toward contemplation of the divine.

- Basilica of Santa Sabina, Rome: Built in the 5th century, Santa Sabina is a prime example of early Christian basilica architecture. Its simple yet elegant design features a long nave with columns and clerestory windows, creating a sense of openness and light.

- San Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna: This 6th-century basilica features a striking mosaic in its apse depicting Saint Apollinaris amid a symbolic landscape, with a cross at its center representing Christ’s sacrifice.

The architectural innovations of this period laid the groundwork for later developments in Romanesque and Gothic styles.

Theological Themes and Symbolism

Early Christian and Byzantine art emphasized theological themes, using symbolism and abstraction to convey complex spiritual ideas. Key themes included:

- Salvation and Redemption: Depictions of Christ as the Good Shepherd or the victorious lamb underscored the promise of salvation for the faithful.

- Heavenly Glory: Gold mosaics, starry ceilings, and angelic figures conveyed the majesty of heaven and the divine order.

- Martyrdom and Saints: Scenes of saints and martyrs highlighted their role as intercessors and examples of faith, inspiring devotion among worshippers.

These themes reflected the central role of faith and spirituality in early Christian and Byzantine culture, with art serving as a visual expression of theological truths.

The Legacy of Early Christian and Byzantine Art in Italy

The art and architecture of this period profoundly influenced the development of Western art. Early Christian basilicas became prototypes for medieval churches, while Byzantine mosaics and iconography inspired generations of artists in Italy and beyond. Ravenna’s mosaics, in particular, remain celebrated for their beauty and spiritual power, drawing visitors from around the world.

By blending classical traditions with Christian spirituality and Byzantine abstraction, Italy’s early Christian and Byzantine art bridged the ancient and medieval worlds, creating a foundation for the artistic achievements of the Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance periods.

Chapter 3: Romanesque and Gothic Art in Italy (1000–1400)

The Romanesque and Gothic periods in Italy represent a pivotal era in art and architecture, marked by the evolution of church design, the rise of monumental sculpture, and the early stirrings of the Renaissance. Romanesque art emphasized strength, simplicity, and spirituality, while Gothic art introduced a sense of verticality, light, and intricate detail. These movements reflected the growing power of the Catholic Church and the development of urban centers, which became hubs for artistic innovation. In Italy, the Romanesque and Gothic styles took on unique characteristics, blending classical influences with northern European elements to create some of the most iconic art and architecture of the Middle Ages.

The Romanesque Style: Strength and Spirituality

The Romanesque period (roughly 1000–1200) is characterized by massive stone architecture, rounded arches, and an emphasis on religious themes. This style reflected the growing influence of monastic communities, which commissioned churches and abbeys to glorify God and accommodate pilgrims.

- Architecture and the Pilgrimage Church: Romanesque churches were designed to inspire awe and accommodate large numbers of worshippers. They often featured thick walls, barrel vaults, and semi-circular arches. Notable examples in Italy include:

- Pisa Cathedral Complex: The Cathedral of Pisa, along with its famous Leaning Tower (a campanile), is a masterpiece of Romanesque architecture. Built between the 11th and 12th centuries, the complex features ornate marble facades and Roman-inspired details, blending northern and classical elements.

- San Miniato al Monte, Florence: This 11th-century basilica is known for its harmonious design and decorative marble facade, which foreshadows the Renaissance interest in geometric patterns.

- Sculptural Innovations: Romanesque sculpture emphasized biblical narratives and moral lessons, often adorning church portals and capitals. Artists like Wiligelmo, who created the detailed reliefs on the Cathedral of Modena, conveyed dramatic, didactic scenes from the Bible with a focus on storytelling and symbolism.

Romanesque art and architecture provided a solid foundation for the more elaborate and expressive Gothic style that followed.

The Gothic Style: Light and Height

The Gothic period (1200–1400) introduced innovations that transformed medieval art and architecture, including pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses. These elements allowed for taller, more graceful structures with large stained-glass windows that filled interiors with light. While Gothic architecture originated in France, Italian artists adapted it to suit their own traditions, resulting in a distinctive style known as Italian Gothic.

- Italian Gothic Architecture:

- Siena Cathedral: One of the most striking examples of Italian Gothic architecture, the Siena Cathedral (Duomo di Siena) features a richly decorated facade by Giovanni Pisano and an elaborate interior adorned with frescoes and mosaic floors. Its striped marble design reflects the Tuscan preference for bold, geometric patterns.

- Orvieto Cathedral: Renowned for its stunning facade by Lorenzo Maitani, the Orvieto Cathedral combines Gothic spires with Romanesque solidity. Its intricate reliefs and vibrant mosaics illustrate biblical scenes with remarkable detail.

- Santa Maria Novella, Florence: This Dominican church blends Gothic architecture with Renaissance elements, featuring a facade by Leon Battista Alberti and a striking use of polychrome marble.

Italian Gothic architecture retained a sense of balance and classical harmony, even as it embraced the verticality and lightness of the Gothic style.

The Rise of Monumental Painting

The Gothic period in Italy also saw significant advancements in painting, as artists began to move away from Byzantine conventions toward greater naturalism and emotional expression. This transition, often called the Proto-Renaissance, laid the groundwork for the artistic revolution of the 15th century.

- Cimabue and Early Innovations: Cimabue (c. 1240–1302) was one of the first Italian painters to break from Byzantine rigidity, incorporating more naturalistic details and spatial depth. His works, such as the Santa Trinita Madonna, hint at the emotional expressiveness that would define later Renaissance art.

- Giotto di Bondone: A student of Cimabue, Giotto (c. 1267–1337) is often considered the father of Western painting. His frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel (Arena Chapel) in Padua revolutionized art with their use of perspective, dynamic compositions, and lifelike figures. Works like The Lamentation capture profound emotion, setting a new standard for narrative art.

- Duccio di Buoninsegna: Active in Siena, Duccio (c. 1255–1319) brought elegance and detail to Gothic painting. His masterpiece, the Maestà Altarpiece for Siena Cathedral, combines Byzantine traditions with a greater emphasis on individual expression and storytelling.

These artists set the stage for the naturalism and humanism of the Renaissance, bridging the medieval and early modern worlds.

Sculptural Achievements

The Gothic period also saw remarkable advancements in sculpture, as Italian artists brought a new sense of dynamism and realism to their work.

- Nicola and Giovanni Pisano: Father and son sculptors Nicola and Giovanni Pisano played a pivotal role in advancing Italian Gothic sculpture. Nicola’s pulpit for the Baptistery of Pisa demonstrates a mastery of classical forms, while Giovanni’s work, such as the facade of Siena Cathedral, blends Gothic intricacy with classical elegance.

- Andrea Pisano: Known for his bronze doors for the Baptistery of Florence, Andrea Pisano’s work exemplifies the transition from Gothic to Renaissance ideals, with clear, balanced compositions and a focus on narrative clarity.

These sculptors helped redefine the role of sculpture in religious and public spaces, paving the way for Renaissance masters like Donatello and Michelangelo.

The Spiritual and Civic Role of Art

Romanesque and Gothic art in Italy was deeply intertwined with both religious devotion and civic pride. Churches and cathedrals were not only places of worship but also symbols of a city’s wealth, power, and piety. Art became a means of expressing communal identity, with cities competing to create the most beautiful and innovative structures.

- Civic Patronage: Wealthy patrons and city governments funded the construction of cathedrals and the commissioning of artworks, fostering a competitive spirit that drove artistic innovation.

- Religious Narratives: Art served as a tool for teaching and inspiring faith, with frescoes, mosaics, and sculptures illustrating biblical stories and moral lessons for the largely illiterate population.

This dual role of art as both spiritual and civic expression reflects the deep integration of religion and society during the Romanesque and Gothic periods.

The Legacy of Romanesque and Gothic Art in Italy

The Romanesque and Gothic periods in Italy laid the groundwork for the Renaissance, fostering a culture of artistic excellence and experimentation. The architectural innovations of Gothic cathedrals, the emotional depth of Giotto’s frescoes, and the narrative clarity of Pisano’s sculptures all contributed to a tradition of creativity that would flourish in the centuries to come.

Italian Romanesque and Gothic art stand as a testament to the enduring power of faith, community, and artistic ambition, shaping the visual and cultural identity of Italy and leaving a legacy that continues to inspire.

Chapter 4: The Italian Renaissance (1400–1600)

The Italian Renaissance represents a golden age of artistic, intellectual, and cultural achievement that transformed Western civilization. Emerging in Florence in the 15th century, the Renaissance was fueled by the rediscovery of classical antiquity, advancements in science and technology, and a renewed focus on humanism. Italian artists and architects broke new ground in their pursuit of naturalism, perspective, and individual expression, creating masterpieces that continue to inspire awe today. This period gave rise to some of history’s greatest artistic geniuses, including Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, as well as profound innovations that redefined art and its purpose.

The Roots of the Renaissance

The Renaissance, meaning “rebirth,” was inspired by a revival of Greco-Roman ideals and fueled by the wealth and patronage of powerful families, such as the Medici of Florence. Humanism, an intellectual movement emphasizing the potential and achievements of humanity, was central to Renaissance thought and profoundly influenced the arts.

- Florence: The Cradle of the Renaissance: Florence’s prosperous economy, thriving banking industry, and influential patrons created a fertile environment for artistic innovation. Figures like Cosimo de’ Medici and Lorenzo de’ Medici supported artists, architects, and scholars, fostering a cultural explosion that would spread throughout Italy and beyond.

- The Rediscovery of Classical Texts: Scholars such as Petrarch and Poggio Bracciolini rediscovered and translated ancient Greek and Roman texts, inspiring artists and thinkers to emulate classical ideals of beauty, proportion, and harmony.

The Early Renaissance: Pioneers of Perspective

The Early Renaissance (1400–1490) marked a transition from Gothic to more naturalistic and classical styles, with artists developing techniques like linear perspective and chiaroscuro to achieve greater realism and depth.

- Filippo Brunelleschi and Linear Perspective: Brunelleschi, an architect and engineer, revolutionized art with his development of linear perspective, a technique that allowed artists to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. His design for the dome of Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore) remains an architectural marvel.

- Masaccio’s Innovations: Masaccio (1401–1428) brought a new level of realism and emotion to painting, as seen in his fresco The Holy Trinity (1427), which demonstrates a masterful use of perspective and human anatomy.

- Donatello’s Sculptural Mastery: Donatello (1386–1466) redefined sculpture with works like David (1440s), the first freestanding nude statue since antiquity, which combines classical ideals with expressive individuality.

These pioneers established the foundations of Renaissance art, combining technical innovation with a renewed focus on humanity and nature.

The High Renaissance: The Age of Genius

The High Renaissance (1490–1520) represents the peak of Renaissance art, characterized by the works of extraordinary individuals who achieved a synthesis of technical mastery, beauty, and intellectual depth.

- Leonardo da Vinci: Often described as the quintessential “Renaissance Man,” Leonardo (1452–1519) excelled as a painter, scientist, and inventor. His masterpiece Mona Lisa (1503–1506) captures enigmatic beauty and psychological depth, while The Last Supper (1495–1498) exemplifies his use of perspective and narrative composition.

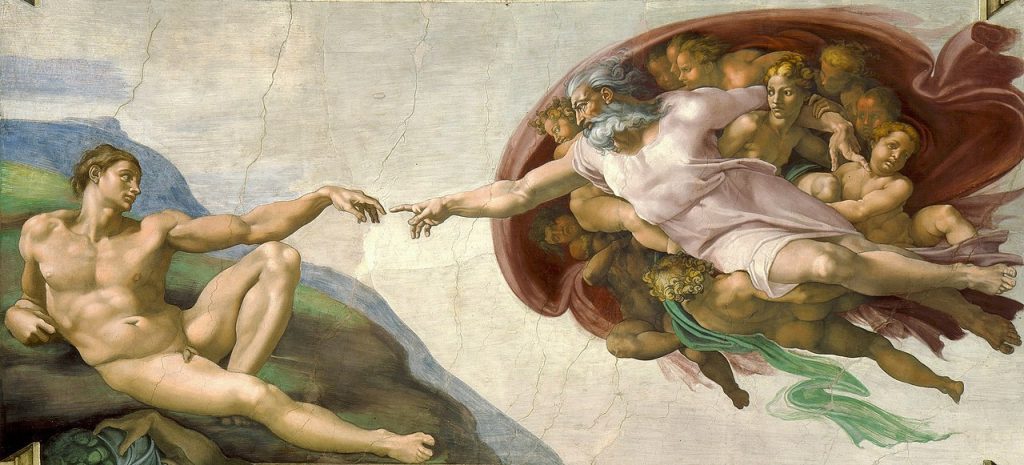

- Michelangelo Buonarroti: Michelangelo (1475–1564) is renowned for his monumental sculptures, such as the David (1501–1504), and his awe-inspiring frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508–1512). His art reflects a profound understanding of anatomy, emotion, and the divine.

- Raphael Sanzio: Raphael (1483–1520) is celebrated for his harmonious compositions and graceful figures, epitomized by The School of Athens (1510–1511), a fresco that symbolizes the union of classical philosophy and Renaissance ideals.

These artists elevated Renaissance art to new heights, blending technical perfection with profound intellectual and spiritual themes.

Renaissance Architecture: Harmony and Innovation

Renaissance architects drew inspiration from ancient Roman designs, emphasizing symmetry, proportion, and geometry. They transformed Italy’s cities with monumental buildings that balanced practicality with beauty.

- Brunelleschi’s Dome: The dome of Florence Cathedral, designed by Brunelleschi, is a masterpiece of engineering and aesthetic innovation, demonstrating the Renaissance commitment to solving practical challenges with artistic vision.

- Leon Battista Alberti: Alberti’s treatise De re aedificatoria (On the Art of Building) codified Renaissance architectural principles, influencing designs such as the Church of Sant’Andrea in Mantua, which combined classical elements with modern functionality.

- Andrea Palladio: Palladio’s villas, such as the Villa Rotonda, reflect a harmonious integration of classical forms and Renaissance ideals, inspiring generations of architects across Europe and beyond.

Renaissance architecture reshaped urban spaces, reflecting the humanist belief in the power of design to improve society.

Renaissance Painting: Naturalism and Emotion

Renaissance painters developed techniques that brought unprecedented realism and emotional depth to their works, capturing the beauty of the natural world and the complexity of human experience.

- Chiaroscuro and Sfumato: Techniques like chiaroscuro (light and shadow) and sfumato (subtle blending of colors) allowed artists to create lifelike textures and atmospheric effects. Leonardo’s Mona Lisa is a prime example of sfumato’s delicate transitions.

- Fresco and Tempera: The Renaissance saw a revival of fresco painting, with artists like Michelangelo and Raphael mastering the medium in grand church commissions. Tempera, a fast-drying medium, was also widely used before the introduction of oil painting.

Patronage and the Role of Art in Society

Renaissance art flourished under the patronage of powerful families, religious institutions, and civic leaders. Art was not only a means of personal expression but also a symbol of status, power, and piety.

- The Medici Family: The Medici of Florence were among the most influential patrons of the Renaissance, commissioning works from artists like Botticelli, Michelangelo, and Leonardo. Their support helped transform Florence into a cultural capital.

- The Papacy: Popes like Julius II and Leo X commissioned monumental works to glorify the Church, including the Sistine Chapel frescoes and St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Patronage played a central role in shaping the Renaissance, providing artists with the resources and opportunities to create their masterpieces.

The Legacy of the Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance profoundly influenced the course of Western art, science, and thought, establishing a foundation for the modern world. Its emphasis on humanism, innovation, and classical ideals continues to resonate, inspiring artists, architects, and thinkers to this day.

From the scientific precision of Leonardo’s sketches to the divine beauty of Michelangelo’s sculptures, the Renaissance represents the pinnacle of artistic achievement and a celebration of human potential. Its legacy is a testament to the enduring power of creativity and the transformative impact of art on society.

Chapter 5: Mannerism and Baroque Art in Italy (1520–1750)

The period following the Italian Renaissance saw a dramatic shift in artistic expression, as Mannerism and Baroque art introduced new ways of engaging audiences. Mannerism, emerging in the early 16th century, rejected the balance and harmony of the High Renaissance in favor of complexity, distortion, and artificial elegance. By the late 16th century, Baroque art took hold, marked by dynamic compositions, intense emotion, and theatrical grandeur. Both movements reflect the turbulent social and religious changes of their time, with Baroque art in particular serving as a tool for the Catholic Church during the Counter-Reformation.

The Mannerist Movement: Elegance and Experimentation

Mannerism developed in the wake of the High Renaissance, as artists sought to push beyond the perfection achieved by figures like Michelangelo and Raphael. This movement emphasized sophistication, tension, and intellectual play, often creating works that appeared deliberately complex and artificial.

- Characteristics of Mannerism:

- Elongated proportions and exaggerated poses.

- Unnatural color palettes, often using pastel tones.

- Ambiguous space and dramatic compositions.

- Pontormo and Parmigianino:

- Jacopo Pontormo: His painting The Deposition (1528) exemplifies Mannerism’s ethereal quality, with elongated figures and an unsettling sense of weightlessness.

- Parmigianino: Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck (1534–1540) is a hallmark of Mannerism, with its distorted figures and luxurious, otherworldly atmosphere.

- Bronzino and Courtly Refinement:

- Agnolo Bronzino: Known for his portraits of the Medici family, Bronzino exemplified the elegance and intellectual complexity of Mannerism. His works, such as Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo (1545), feature meticulous detail and a sense of aristocratic detachment.

Mannerism reflected the intellectual and cultural sophistication of the Italian courts, creating art that was meant to challenge and intrigue rather than simply please.

The Baroque: Drama and Emotion

By the late 16th century, the Baroque style emerged as a reaction against Mannerism’s artificiality, seeking to engage audiences with dramatic, emotional, and immersive experiences. The Catholic Church played a significant role in fostering Baroque art, using it to inspire devotion and counter the Protestant Reformation.

- Characteristics of Baroque Art:

- Dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro and tenebrism).

- Dynamic, swirling compositions that create a sense of movement.

- Emotional intensity and theatricality.

- Caravaggio and the Power of Light:

- Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) revolutionized painting with his use of tenebrism, a technique that emphasized stark contrasts between light and dark. Works like The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600) and Judith Beheading Holofernes (1598–1599) combine dramatic storytelling with intense realism, making religious themes accessible and immediate.

- Bernini and the Theatricality of Sculpture:

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) defined Baroque sculpture with works that seem to burst into motion. His Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–1652) in the Cornaro Chapel blends architecture, sculpture, and light to create a spiritual and emotional experience.

- Bernini also transformed Rome with his architectural projects, including the colonnade of St. Peter’s Square, designed to embrace and welcome visitors to the Vatican.

Baroque art sought to captivate and inspire, creating a multisensory experience that drew viewers into the heart of its narratives.

Baroque Architecture: Monumental and Ornate

Baroque architecture embraced grandeur, complexity, and ornamentation, transforming Italy’s cities and religious spaces into showcases of splendor.

- Key Features:

- Use of curves, domes, and dramatic spatial effects.

- Integration of sculpture, painting, and architecture into cohesive designs.

- Lavish decoration, often with gilded details and marble inlays.

- Borromini’s Vision:

- Francesco Borromini (1599–1667) created some of the most innovative Baroque architecture, including San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome. His designs used undulating facades and dynamic interior spaces to create a sense of movement and energy.

- Churches as Theatrical Spaces:

- Baroque churches, such as the Jesuit Church of Il Gesù in Rome, were designed to evoke awe and wonder, with frescoed ceilings and dramatic altarpieces drawing the viewer’s gaze upward.

Baroque architecture reflected the power and glory of the Catholic Church, using space and ornamentation to convey spiritual transcendence.

Frescoes and Ceiling Paintings

Baroque artists extended their dramatic vision to ceilings and walls, using illusionistic techniques to dissolve the boundaries between real and painted space.

- Pietro da Cortona: His ceiling fresco The Triumph of Divine Providence (1633–1639) in the Palazzo Barberini creates an illusion of infinite space, with figures soaring into the heavens in a celebration of divine power.

- Andrea Pozzo: Pozzo’s Apotheosis of Saint Ignatius (1691–1694) in the Church of Sant’Ignazio in Rome is a masterpiece of trompe-l’œil, blending architecture and painting to create an awe-inspiring vision of heaven.

These monumental frescoes represent the Baroque’s ability to overwhelm and inspire through sheer scale and technical brilliance.

Themes of Mannerism and Baroque Art

The themes of Mannerism and Baroque art reflect the social, religious, and political forces of their time:

- Mannerism:

- Elegance, refinement, and intellectual complexity.

- A fascination with ambiguity, distortion, and the limits of artistic conventions.

- Baroque:

- The triumph of the Catholic Church and the drama of divine intervention.

- Emotional intensity and the human experience of faith and redemption.

- Power, authority, and the grandeur of the state.

These themes reflect the profound changes in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries, as art became a means of engaging with and influencing society.

The Legacy of Mannerism and Baroque Art in Italy

Mannerism and Baroque art left an indelible mark on Western art, setting new standards for creativity, technical mastery, and emotional engagement. The Mannerists challenged conventions and expanded the possibilities of artistic expression, while Baroque artists revolutionized the way art could communicate with its audience.

These movements continue to inspire artists and architects, their works serving as enduring examples of art’s ability to reflect and shape human experience. From the refined elegance of Pontormo to the dramatic power of Bernini, Mannerism and Baroque art remain vital chapters in Italy’s extraordinary artistic legacy.

Chapter 6: Neoclassicism and the Age of Revolution in Italy (1750–1850)

The Neoclassical period marked a return to the clarity, order, and ideals of Greco-Roman antiquity, driven by archaeological discoveries, Enlightenment thought, and a reaction against the excesses of Baroque and Rococo styles. For Italy, this era also coincided with revolutionary fervor and the rise of nationalism, as the country began its struggle for unification. Italian artists and architects found inspiration in ancient Rome, blending classical themes with the aspirations of their age. Neoclassicism became the dominant style for public monuments, civic architecture, and history painting, reflecting both intellectual ideals and political ambitions.

The Roots of Neoclassicism

The Neoclassical movement arose in the mid-18th century, influenced by archaeological discoveries at ancient sites like Pompeii and Herculaneum. These excavations sparked a fascination with classical art and architecture, inspiring artists to emulate the simplicity, symmetry, and moral seriousness of antiquity.

- Pompeii and Herculaneum: The rediscovery of these ancient Roman cities in the 1740s provided a wealth of artifacts and frescoes, offering a glimpse into classical life. The vivid colors and meticulous details of Pompeian art influenced Neoclassical painting, interior design, and decorative arts.

- The Grand Tour: Wealthy Europeans traveled to Italy to study its ancient ruins and Renaissance treasures, spreading Neoclassical ideals across the continent. Italian cities like Rome and Naples became key stops on this cultural pilgrimage.

Neoclassicism appealed to Enlightenment thinkers for its association with reason, civic virtue, and universal ideals, contrasting with the ornate decadence of the Rococo.

Antonio Canova: The Master of Neoclassical Sculpture

Antonio Canova (1757–1822) is widely regarded as the greatest Neoclassical sculptor, known for his idealized depictions of mythological and historical subjects. His works reflect a mastery of form, grace, and emotional restraint, embodying the Neoclassical pursuit of timeless beauty.

- Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1787–1793): This sculpture captures a moment of tender emotion, blending classical proportions with a sense of romantic intimacy.

- Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker (1806): Commissioned by Napoleon, this colossal statue depicts the emperor as a classical hero, reinforcing his image as a ruler of destiny and power.

- The Tomb of Maria Christina of Austria (1798–1805): Canova’s funerary monument in Vienna combines allegorical figures with a sense of serene solemnity, showcasing his ability to merge classical ideals with personal expression.

Canova’s work epitomizes Neoclassical sculpture, achieving a balance between technical perfection and emotional depth.

Neoclassical Painting in Italy

Neoclassical painters in Italy sought to convey moral lessons and civic ideals through depictions of historical and mythological subjects. Their works emphasized clarity, narrative, and dramatic composition, often serving political and educational purposes.

- Vincenzo Camuccini: Known as the “Italian David” for his stylistic similarities to French Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David, Camuccini created monumental history paintings that celebrated heroism and virtue. His work The Death of Julius Caesar (1806) exemplifies Neoclassical themes of sacrifice and patriotism.

- Andrea Appiani: Appiani became the official painter of Napoleon’s Italian court, producing portraits and allegorical works that celebrated the emperor’s achievements. His frescoes in the Royal Palace of Milan reflect his refined technique and classical inspiration.

Neoclassical painting in Italy served as a vehicle for political propaganda and cultural pride, reflecting the aspirations of a nation on the verge of transformation.

Architecture and Urban Renewal

Neoclassical architecture reshaped Italy’s cities, drawing from ancient Roman models to create buildings that symbolized civic virtue and national identity. Architects employed columns, pediments, and symmetrical layouts to evoke the grandeur of antiquity.

- The Church of San Francesco di Paola, Naples: Modeled after the Pantheon, this Neoclassical church reflects the influence of ancient Roman architecture, with its massive dome and colonnaded portico.

- The Cimitero Monumentale, Milan: This monumental cemetery, designed in the Neoclassical style, combines solemnity with architectural elegance, embodying the ideals of memory and civic responsibility.

- Urban Planning: Italian cities like Turin and Milan underwent significant Neoclassical redesigns, with new public squares, avenues, and monuments emphasizing order and grandeur.

Neoclassical architecture in Italy reflected both the intellectual ideals of the Enlightenment and the growing sense of national identity.

Art and the Age of Revolution

The Neoclassical era in Italy coincided with significant political upheaval, including Napoleon’s campaigns, the fall of the Papal States, and the early stages of the Italian unification movement. Art played a crucial role in shaping and expressing the ideals of this revolutionary age.

- Napoleonic Influence: Napoleon’s conquest of Italy brought French Neoclassical ideals to the forefront, as Italian artists and architects contributed to his vision of empire. Monuments and public works celebrated his military victories and emphasized the connection between modern rulers and ancient Rome.

- Nationalism and Patriotism: Italian artists used Neoclassical imagery to evoke the glory of ancient Rome and inspire a sense of national pride. This association with Italy’s classical past became a powerful tool in the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification.

Art during this period reflected the tensions and aspirations of a nation navigating the transition from fragmented states to a unified identity.

The Legacy of Neoclassicism in Italy

Neoclassicism left an enduring impact on Italian art and architecture, revitalizing the nation’s connection to its classical heritage and laying the groundwork for the Romantic and modern movements that followed. Its emphasis on clarity, order, and moral purpose continues to resonate, influencing public monuments, civic spaces, and artistic traditions.

From the sculptures of Antonio Canova to the grand urban designs of Neoclassical architects, this period represents a fusion of ancient ideals and modern ambitions. Neoclassicism not only celebrated Italy’s past but also looked toward its future, reflecting the intellectual and political dynamism of a nation on the cusp of transformation.

Chapter 7: Italian Romanticism and Realism (1800–1900)

The 19th century was a time of profound change for Italy, as the country experienced political revolutions, social upheavals, and the eventual unification of its fragmented states into a single nation. These events deeply influenced Italian art, which shifted from the Neoclassical ideals of reason and order to the emotional intensity of Romanticism and the unvarnished depictions of Realism. Italian artists of this period grappled with themes of identity, freedom, and modernity, using their work to reflect and shape the aspirations of their society.

Romanticism: Passion and National Identity

Romanticism emerged in Italy in the early 19th century, emphasizing emotion, individuality, and the sublime. The movement was shaped by the struggles for independence and unification, known as the Risorgimento, and it often drew on history, literature, and nature to inspire a sense of national pride and unity.

- Francesco Hayez: The Face of Italian Romanticism

- Francesco Hayez (1791–1882) is considered Italy’s leading Romantic painter. His works often combined historical themes with emotional intensity, capturing the spirit of the Risorgimento.

- The Kiss (1859): Hayez’s most famous painting, The Kiss, became a symbol of Italian unification. The intimate yet patriotic scene of a couple’s embrace suggests both personal and political passion, resonating with Italy’s fight for independence.

- Hayez’s historical works, such as The Refugees of Parga (1826), often depicted moments of human suffering and resilience, blending Romantic drama with moral commentary.

- The Romantic Landscape

- Romanticism in Italy also found expression in landscapes that celebrated the natural beauty of the Italian countryside. Artists like Giuseppe Bezzuoli and Carlo Canella painted sweeping vistas imbued with a sense of the sublime, reflecting both the power of nature and the longing for national unity.

The Transition to Realism

By the mid-19th century, Italian art began to shift toward Realism, a movement that sought to depict life as it truly was, without idealization. Inspired by the social and political changes of the time, Realist artists turned their attention to everyday subjects, focusing on rural life, urban poverty, and the working class.

- The Macchiaioli Movement

- The Macchiaioli, a group of Tuscan painters active in the 1850s and 1860s, were Italy’s most significant contributors to Realism. Their name, derived from the Italian word macchia (spot), reflects their technique of using patches of color to capture light and shadow, prefiguring Impressionism.

- Key Figures:

- Giovanni Fattori: Known for his depictions of rural life and military scenes, such as The Rotunda of Palmieri (1866), Fattori captured the dignity and hardship of everyday existence.

- Silvestro Lega: Lega’s works, such as The Pergola (1868), often portrayed domestic and pastoral scenes with sensitivity and attention to detail.

- Telemaco Signorini: Signorini’s paintings, including The Ghetto of Venice (1885), explored urban settings and social inequalities, highlighting the struggles of marginalized communities.

- Realism and the Risorgimento

- Realist artists were deeply engaged with the political struggles of the Risorgimento, depicting soldiers, revolutionaries, and ordinary citizens involved in the fight for independence. Their work celebrated the heroism of everyday life while documenting the realities of war and poverty.

Themes of Romanticism and Realism

The art of this period reflected the tensions and aspirations of 19th-century Italy, blending Romantic idealism with Realist observation.

- Romanticism:

- Themes of love, heroism, and sacrifice were central to Romantic art, often expressed through historical and literary subjects.

- The natural world was depicted as a source of inspiration and reflection, symbolizing the grandeur and challenges of the human condition.

- Realism:

- Realist art focused on the struggles and dignity of ordinary people, capturing the realities of labor, poverty, and rural life.

- The movement also addressed social and political issues, reflecting the changing dynamics of a rapidly modernizing society.

These themes resonated with Italian audiences, reflecting both their aspirations for freedom and the complexities of their lived experiences.

The Impact of Photography and Modernity

The advent of photography in the mid-19th century influenced both Romantic and Realist art, providing new tools for observation and documentation. While some artists saw photography as a threat to traditional painting, others embraced its potential to capture fleeting moments and enhance their study of light, composition, and detail.

- Realist Techniques: The Macchiaioli’s use of patches of color to capture light and shadow was partly inspired by the immediacy of photographic images, bridging the gap between traditional painting and modern approaches to representation.

Sculpture in the Romantic and Realist Era

Italian sculptors of the 19th century also contributed to Romantic and Realist movements, creating works that balanced dramatic emotion with meticulous craftsmanship.

- Lorenzo Bartolini: A Neoclassical sculptor influenced by Romantic ideals, Bartolini created works like Charity (1839), which combined classical forms with tender, emotional expressions.

- Vincenzo Vela: A leading Realist sculptor, Vela’s The Victims of Labor (1882) captured the plight of industrial workers with striking detail and empathy, reflecting the social concerns of the era.

Sculpture during this period became a means of exploring both personal emotion and collective struggle, mirroring the broader themes of Romanticism and Realism.

The Legacy of 19th-Century Italian Art

The Romantic and Realist movements in Italy left a lasting impact on the nation’s artistic identity, bridging the gap between the idealism of the Renaissance and the modernism of the 20th century. Romanticism inspired Italians to imagine a unified and independent nation, while Realism documented the challenges and triumphs of the everyday people who made that dream a reality.

Through their focus on emotion, narrative, and social engagement, Italian artists of the 19th century created works that continue to resonate, offering a vivid window into a pivotal moment in the nation’s history.

Chapter 8: The Futurist Movement and Early Modernism in Italy (1900–1945)

The early 20th century was a time of dramatic change for Italy, as industrialization, technological advancements, and political shifts transformed society. Italian artists responded with revolutionary new approaches to art, embracing modernism and rejecting traditional forms. The Futurist Movement, one of the most significant avant-garde movements of the time, sought to capture the dynamism, energy, and speed of the modern world. Alongside Futurism, Italian artists explored other modernist styles, including abstraction, metaphysical painting, and surrealism, creating a rich and diverse artistic landscape.

The Rise of Futurism: A Manifesto for Modernity

Futurism was founded in 1909 by poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, whose Futurist Manifesto, published in Paris, celebrated modern technology, industry, and the energy of contemporary life. The movement sought to break completely with the past, embracing innovation and revolution in all forms of art.

- Key Ideas of Futurism:

- Glorification of speed, machinery, and progress.

- Rejection of traditional art forms, museums, and historical institutions.

- Focus on themes of movement, energy, and the industrial age.

- Emphasis on urban life, war, and the triumph of the machine.

- The First Futurist Painters:

- Umberto Boccioni: Boccioni was a leading figure in Futurist painting and sculpture. His works, such as Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), captured the dynamism and fluidity of motion, using abstract forms to represent energy and movement.

- Giacomo Balla: Balla’s painting Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912) exemplifies Futurism’s obsession with capturing the mechanics of motion, using repeated forms to create the sensation of movement.

- Gino Severini: Severini’s works, such as Armored Train in Action (1915), celebrated modern technology and warfare, reflecting the Futurists’ fascination with the power and destruction of machines.

Futurism sought to revolutionize not only painting and sculpture but also poetry, music, theater, and design, creating a totalizing vision of modern art.

Futurist Sculpture and Architecture

Futurist ideas extended into three-dimensional art and urban planning, as artists and architects sought to reshape Italy’s physical and cultural landscape.

- Boccioni’s Sculptural Innovations: Works like Unique Forms of Continuity in Space pushed the boundaries of traditional sculpture, using abstract forms to evoke speed and motion. This approach influenced generations of modern sculptors.

- Antonio Sant’Elia and Futurist Architecture: Sant’Elia’s visionary designs for a “Futurist City” imagined towering skyscrapers, mechanized transportation systems, and dynamic urban environments. Though unrealized, his ideas inspired modernist architecture and urban planning.

Futurist sculpture and architecture emphasized bold, experimental forms that reflected the spirit of modernity.

Metaphysical Painting: The World of De Chirico

As Futurism dominated the early 20th century, another Italian movement emerged with a more introspective and surreal approach. Metaphysical painting, founded by Giorgio de Chirico, explored themes of mystery, dreamlike spaces, and the uncanny.

- Giorgio de Chirico: De Chirico’s works, such as The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon (1910) and The Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (1914), feature empty urban landscapes, classical architecture, and enigmatic figures. These paintings evoke a sense of stillness and foreboding, contrasting sharply with the dynamism of Futurism.

- Carlo Carrà: Initially a Futurist, Carrà later embraced metaphysical painting, creating works like The Engineer’s Lover (1921), which combine everyday objects with surreal arrangements.

Metaphysical painting influenced the development of Surrealism, offering a new way of exploring the subconscious and the psychological depths of modern life.

The Impact of Fascism on Italian Art

The rise of Fascism under Benito Mussolini in the 1920s had a profound impact on Italian art. While some artists aligned themselves with the regime’s emphasis on nationalism and modernity, others resisted or adapted their work to avoid political conflict.

- Fascist Aesthetic: Mussolini’s regime promoted a combination of modernism and classical revival, using art and architecture to convey power, order, and grandeur. Public projects, such as the EUR district in Rome, reflected this synthesis of ancient Roman forms and modernist styles.

- Futurism and Fascism: Many Futurists, including Marinetti, supported Fascism, believing that its emphasis on strength and progress aligned with their ideals. However, the regime’s preference for traditional imagery led to tensions with the more experimental aspects of Futurism.

- State Control and Propaganda: Artists who resisted Fascist ideology faced censorship and persecution. Some turned to abstraction or metaphysical themes to distance themselves from political messages.

The intersection of modernist art and Fascist politics created a complex and often contradictory artistic landscape during this period.

Surrealism and Abstraction in Italian Art

In the 1930s and 1940s, Italian artists began to explore surrealism and abstraction, influenced by international movements and their own cultural traditions.

- Lucio Fontana: Fontana, who would later become a leading figure in post-war art, began experimenting with abstraction in the 1930s, blending modernist forms with traditional Italian craftsmanship.

- Arturo Martini: A sculptor known for his exploration of abstraction and mythology, Martini created works that bridged the gap between modernist innovation and classical themes.

Surrealism and abstraction allowed Italian artists to address universal themes while navigating the constraints of political and social change.

The Legacy of Futurism and Early Modernism in Italy

The Futurist movement and early modernist art in Italy left a profound legacy, influencing international avant-garde movements and shaping the course of modern art. Futurism’s embrace of technology, motion, and innovation resonated far beyond Italy, inspiring artists in fields as diverse as design, performance, and cinema. Meanwhile, metaphysical painting opened new doors for exploring the subconscious, paving the way for surrealism and conceptual art.

This period of experimentation and transformation set the stage for Italy’s post-war art movements, as Italian artists continued to push boundaries and redefine their national identity in a rapidly changing world.

Chapter 9: Post-War and Contemporary Italian Art (1945–Present)

The aftermath of World War II brought profound change to Italy, as the nation rebuilt itself both physically and culturally. Italian artists, shaped by the trauma of war and the challenges of modernization, began to explore new directions in art that reflected the complexities of the contemporary world. From the radical experimentation of Arte Povera to the conceptual provocations of modern artists like Maurizio Cattelan, post-war Italian art has been characterized by innovation, social critique, and a deep engagement with global trends.

The Reconstruction Era and Abstract Expressionism

In the immediate post-war years, Italian artists sought to move beyond the representational art of the past, embracing abstraction and experimental techniques.

- Lucio Fontana: Spatialism and Innovation

- Fontana (1899–1968) became one of the leading figures of post-war Italian art with his creation of Spatialism, an art movement that sought to merge painting, sculpture, and architecture into a new spatial dimension.

- His iconic Concetto Spaziale (Spatial Concepts) series features canvases slashed with precise cuts, challenging traditional notions of surface and medium while inviting viewers to consider the space beyond the artwork.

- Alberto Burri: The Material Revolution

- Burri (1915–1995) pioneered the use of unconventional materials like burlap, plastic, and tar in his works, creating abstract compositions that reflected the scars of war. His Sacchi (Sacks) series (1940s–1950s), made from stitched and burned materials, evoke themes of destruction and reconstruction.

These artists helped establish Italy’s reputation as a hub of post-war modernism, introducing new forms of abstraction and material exploration.

Arte Povera: Radical Experimentation

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Arte Povera movement emerged as a reaction against consumerism and traditional art forms. Literally meaning “poor art,” Arte Povera emphasized the use of everyday materials and a rejection of commercialism.

- Key Figures of Arte Povera:

- Michelangelo Pistoletto: Pistoletto’s iconic Mirror Paintings incorporate reflective surfaces that engage viewers as participants in the artwork, blurring the line between art and life.

- Mario Merz: Known for his use of organic materials and neon lighting, Merz explored themes of nature, energy, and the passage of time, as seen in his igloo-like installations.

- Giuseppe Penone: Penone’s works often highlight the relationship between humanity and nature, using materials like wood, stone, and leaves to create poetic installations.

- Themes and Techniques:

- Arte Povera artists used humble materials like earth, cloth, and found objects to critique industrialization and consumer culture.

- Their works often explored themes of transformation, decay, and the interconnectedness of human and natural systems.

Arte Povera challenged the conventions of the art world, offering a uniquely Italian perspective on the global avant-garde.

Conceptual and Political Art

The post-war period also saw the rise of conceptual art in Italy, as artists used their work to question societal norms, politics, and the role of art itself.

- Piero Manzoni: Manzoni (1933–1963) is best known for his provocative conceptual works, such as Artist’s Shit (1961), in which he canned and sold his own excrement as a critique of the commodification of art. His ironic and subversive works pushed the boundaries of artistic expression.

- Alighiero Boetti: Boetti’s works, such as his embroidered world maps (Mappa series), combine conceptual rigor with a playful exploration of systems, language, and global identity.

Italian conceptual artists used humor, irony, and intellectual engagement to challenge traditional ideas about art and its role in society.

Contemporary Italian Art

In recent decades, Italian art has continued to evolve, reflecting global trends while maintaining a distinct cultural identity. Contemporary Italian artists have explored themes ranging from identity and memory to the impact of technology and globalization.

- Maurizio Cattelan: Provocative Humor

- Cattelan (b. 1960) is known for his provocative and satirical works, such as America (2016), a fully functional solid gold toilet, and La Nona Ora (The Ninth Hour) (1999), a sculpture of Pope John Paul II struck by a meteorite. His art often challenges authority, institutions, and societal norms.

- Vanessa Beecroft: Performance and Identity

- Beecroft (b. 1969) creates performance art and installations that examine themes of gender, beauty, and the human body. Her works often feature live models in carefully orchestrated tableaux, creating a tension between intimacy and spectacle.

- Adelita Husni-Bey: Social Engagement

- Husni-Bey (b. 1985) explores themes of collective action, education, and social justice through video, performance, and participatory workshops. Her work reflects a commitment to addressing contemporary issues and fostering community dialogue.

Themes in Post-War and Contemporary Italian Art

Italian art from 1945 to the present has been marked by its engagement with critical themes:

- Reconstruction and Renewal: Reflecting the challenges of rebuilding after World War II, artists explored themes of destruction, recovery, and resilience.

- Critique of Consumerism: Movements like Arte Povera and conceptual art challenged the materialism and commodification of modern society.

- Global Identity: Contemporary artists have addressed issues of migration, globalization, and cultural hybridity, reflecting Italy’s evolving role in the world.

These themes highlight the adaptability and relevance of Italian art in a rapidly changing global context.

The Legacy of Post-War and Contemporary Italian Art

Italy’s post-war and contemporary art scene has left a lasting mark on the global art world, fostering bold experimentation and pushing the boundaries of creativity. From the radical innovations of Lucio Fontana and Arte Povera to the provocative humor of Maurizio Cattelan, Italian artists have consistently challenged conventions while engaging deeply with their cultural and historical roots.

This period reflects the resilience and dynamism of Italian art, offering a testament to its ability to evolve and remain at the forefront of global artistic innovation.

You’re correct—based on the earlier outline, there should be 11 chapters for Italian art history. It seems I’ve condensed the final themes into a single concluding chapter. Let me clarify and expand to align with the structure. The missing chapter would focus on Italian Design and Global Influence (20th Century to Present), emphasizing Italy’s contributions to industrial design, fashion, and architecture.

Let me craft Chapter 10: Italian Design and Global Influence and revise the final conclusion to be Chapter 11.

Chapter 10: Italian Design and Global Influence (20th Century to Present)

Italy’s artistic genius is not limited to painting and sculpture; its influence extends deeply into design, fashion, and architecture. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Italy emerged as a global leader in these fields, blending creativity, craftsmanship, and functionality to shape modern aesthetics. From iconic furniture and industrial design to cutting-edge fashion and architectural innovation, Italian design reflects the nation’s enduring commitment to beauty and innovation.

Industrial Design: Art Meets Functionality

Italian industrial design rose to prominence in the mid-20th century, combining sleek modernist principles with an appreciation for aesthetics and craftsmanship.

- Olivetti and the Marriage of Form and Function:

- The Olivetti company, known for its typewriters and office equipment, exemplified Italian industrial design’s commitment to beauty and utility. Products like the Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter (1950) became icons of modern design, celebrated for their sleek lines and ergonomic functionality.

- Design for the Home:

- Italian designers like Achille Castiglioni and Gae Aulenti revolutionized furniture and lighting design with innovative creations that balanced artistry and practicality. Castiglioni’s Arco Lamp (1962) remains a staple of modern interiors.

Italian industrial design shaped global trends, influencing fields as diverse as automotive design, consumer electronics, and urban planning.

Fashion: Italy’s Global Style Revolution

Italian fashion became synonymous with luxury and sophistication in the mid-20th century, establishing the nation as a global hub for haute couture and ready-to-wear design.

- The Birth of Modern Italian Fashion:

- The post-war boom saw the rise of Italian fashion houses like Gucci, Prada, and Armani, which combined traditional craftsmanship with contemporary style. The “Made in Italy” label became a mark of quality and innovation.

- Milan as a Fashion Capital:

- By the 1980s, Milan had established itself as one of the world’s leading fashion capitals, rivaling Paris and New York. Designers like Giorgio Armani redefined modern elegance, while brands like Versace pushed the boundaries of bold, avant-garde fashion.

Italian fashion continues to set trends, blending timeless elegance with modern innovation.

Architecture: Bridging Tradition and Modernity

Italian architects have played a pivotal role in shaping both historical preservation and contemporary design, blending tradition with cutting-edge innovation.

- Post-War Reconstruction and Modernism:

- Architects like Gio Ponti and Renzo Piano redefined modern Italian architecture, creating structures that married functionality with aesthetic brilliance.

- Renzo Piano’s Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Shard in London are celebrated for their innovative designs and global impact.

- Sustainability and Innovation:

- Contemporary Italian architecture emphasizes sustainable practices, with projects like Stefano Boeri’s Bosco Verticale (Vertical Forest) in Milan integrating greenery and urban living.

Italian architecture remains a testament to the nation’s ability to balance heritage with forward-thinking design.

Cinema, Cars, and Cultural Icons

Italy’s design ethos extends to its cinema, automotive industry, and cultural production, reinforcing its global influence.

- Italian Cinema and Style:

- Directors like Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni integrated Italian design into their films, using sets, costumes, and cinematography to reflect the elegance and drama of Italian culture.

- Automotive Design:

- Brands like Ferrari, Lamborghini, and Fiat exemplify Italian design’s ability to combine luxury, performance, and style, making Italian cars symbols of excellence worldwide.

Legacy and Global Impact

Italian design, whether in fashion, architecture, or industrial production, reflects a deep connection to artistry and innovation. Its global influence is evident in everything from iconic furniture pieces to luxury cars, cementing Italy’s status as a leader in creative industries.

Chapter 11: Conclusion: The Legacy of Italian Art

Italy’s contribution to the history of art is unparalleled, encompassing every major epoch from ancient Rome to the contemporary period. The nation has been the birthplace of transformative movements, revolutionary ideas, and visionary artists who have defined and redefined the course of Western art. Italian art is not merely a testament to technical brilliance but also a reflection of the values, struggles, and aspirations that have shaped its culture.

Italy’s Artistic Journey

Across centuries, Italian art has consistently pushed boundaries while honoring its rich traditions:

- Ancient Rome: Laid the foundation for Western architecture and realism with its monumental buildings and lifelike sculptures.

- The Renaissance: Elevated art to its intellectual and spiritual heights, blending humanism with technical mastery.

- Modern Movements: Pioneered avant-garde styles like Futurism and Arte Povera, challenging conventions and embracing the modern world.

- Design and Beyond: Redefined aesthetics in industrial design, fashion, and architecture, influencing global trends.

Each era has left an indelible mark, contributing to a narrative of constant evolution and innovation.

Themes That Resonate Across Centuries

Italian art is characterized by recurring themes that transcend time:

- Humanism: From Renaissance portraits to contemporary installations, Italian art celebrates the complexity and potential of the human experience.

- Nature and the Divine: Religious and secular works alike explore humanity’s relationship with the natural world and the cosmos.

- Tradition and Innovation: Italian art seamlessly balances reverence for the past with an openness to experimentation, ensuring its enduring relevance.

These themes ensure that Italian art remains both timeless and adaptable, resonating with audiences worldwide.

Italy’s Global Legacy

The influence of Italian art and design is woven into the fabric of global culture. From Michelangelo’s frescoes to the sleek lines of a Ferrari, Italy’s creativity has shaped the way we see and experience the world. Its museums, fashion houses, and cultural landmarks continue to attract millions of visitors, fostering a universal appreciation for beauty, craftsmanship, and innovation.

A Future Rooted in Creativity

Italian art is not merely a relic of the past—it is a living tradition that continues to evolve. Contemporary artists, architects, and designers engage with pressing global issues, from sustainability to social justice, while drawing inspiration from the nation’s deep cultural roots. Italy’s cities, from Florence to Milan, remain vibrant centers of creativity, attracting new generations of talent.

The Eternal Spirit of Italian Art

The story of Italian art is a celebration of human ingenuity, resilience, and the power of creativity to transform the world. From the grandeur of ancient Rome to the conceptual provocations of today, Italian art invites us to reflect, imagine, and connect with the universal truths that define our shared humanity.

As Italy continues to inspire and innovate, its legacy endures as a cornerstone of Western culture, a testament to the timeless power of art to shape and elevate our lives.