The 1920s marked an era of bold experimentation and growing financial opportunity for American artists. Following World War I, the U.S. economy boomed, and an expanding class of wealthy patrons fueled the commercial art market. Wealthy industrialists and business magnates invested in art collections to signal sophistication and civic status. Private galleries flourished in cities like New York, and art auctions reached unprecedented prices. In 1929 alone—just before the crash—art sales were valued at around $6 million nationwide.

This environment encouraged artists to take creative risks, often drawing inspiration from European movements like Cubism, Dadaism, and Futurism. The influence of these styles was particularly evident in works by Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and Georgia O’Keeffe, who used abstraction and surrealism to express modern life. Meanwhile, American art institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art (founded in 1929), began forming collections with an international scope. Modernism became fashionable among elite collectors, who viewed art as both a cultural investment and a speculative asset.

Avant-Garde Movements and Urban Centers

New York and Chicago emerged as the country’s dominant art hubs during the 1920s. New York in particular, with its concentration of museums, galleries, and art schools, was the epicenter of the avant-garde. Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery played a critical role in promoting artists like John Marin, Charles Demuth, and O’Keeffe. The city’s cosmopolitan energy offered a receptive environment for innovations in both painting and photography.

At the same time, Chicago cultivated its own vibrant art scene, with the Art Institute of Chicago promoting American modernists alongside European names. Artists working in these cities were often responding to themes of industrial growth, urban life, and psychological fragmentation—subjects aligned with modernist sensibilities. These urban movements, however, were largely disconnected from the lives of ordinary Americans, particularly those in rural and working-class communities. This disconnect would become glaringly apparent after 1929, when audiences demanded more relatable and socially grounded art.

Vulnerabilities Beneath the Surface

Despite its vibrancy, the American art world of the 1920s rested on an unstable foundation. The market was propped up by a narrow slice of society—the wealthy elite—whose patronage was tied closely to stock market gains and inherited fortunes. When the stock market crashed in October 1929, much of the support structure for fine art disappeared almost overnight. Galleries closed or downsized, and museum acquisitions were slashed due to evaporating endowments.

In addition, many artists found themselves isolated from broader audiences. Modernist abstraction, though popular among certain urban elites, was often viewed as obscure or even alienating by rural Americans. The dominance of this style in pre-Depression circles meant that few artists had established reputations beyond elite buyers and critics. This lack of mainstream resonance contributed to the rapid downfall of avant-garde movements as economic hardship spread. When survival—not theory—became the nation’s focus, art had to change its message and its messengers.

Artists of the 1920s and their dominant styles:

- Georgia O’Keeffe – Modernist abstraction, Southwest landscapes

- Charles Demuth – Precisionism, industrial scenes

- Edward Hopper – Urban realism, loneliness, alienation

- Arthur Dove – Organic abstraction

- John Marin – Expressionist cityscapes

- Charles Sheeler – Photography-influenced realism

The Lost Generation Artists in America

Though the term “Lost Generation” is often associated with writers like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, many visual artists shared in the cultural disillusionment that defined the post–World War I period. American artists such as Stuart Davis, Gerald Murphy, and Man Ray spent significant time in Europe during the 1920s, drawn to Paris’s experimental energy and modernist movements. However, by the late 1920s, several returned to the United States, looking for new inspiration closer to home.

These artists brought back ideas but struggled to find a place in a rapidly commercializing American art scene. Their works, often intellectual and symbolic, were ill-suited to the tastes of American buyers outside of major cities. This sense of alienation foreshadowed the deeper fracture between avant-garde and popular art that would become glaringly obvious after 1929. The Depression forced many to reevaluate whether art should serve personal expression, public purpose, or both.

Crisis and Response — The Artist’s World After 1929

Economic Collapse and Vanishing Patrons

The Wall Street Crash of October 24, 1929, known as Black Thursday, signaled the beginning of a massive economic contraction. By 1932, U.S. unemployment had reached nearly 25%, and poverty spread across urban and rural areas alike. For artists, the collapse meant the evaporation of private commissions, reduced gallery space, and lost teaching jobs. Artists who had once enjoyed generous patronage were suddenly competing for scraps, and many were forced to abandon their craft or seek manual labor.

Museums and cultural institutions also suffered, canceling exhibitions and suspending purchases due to endowment losses. A 1931 survey from the American Federation of Arts found that half of the country’s smaller galleries had shut down. The Depression not only crushed the financial underpinnings of the art market—it also shifted the nation’s aesthetic priorities. Abstract art, seen as elitist and detached, gave way to more narrative-driven, emotionally direct, and socially conscious styles that addressed the struggles of ordinary people.

A Shift in Subject Matter and Tone

By the early 1930s, artists began to shift away from cosmopolitan modernism toward themes rooted in the American experience. Social realism emerged as a powerful genre, with painters and photographers portraying breadlines, eviction scenes, tenant farmers, and factory workers. These images were not only visually compelling but also politically resonant, revealing the human toll of economic failure. Their accessibility helped re-establish the importance of art in public life.

This new tone emphasized honesty over style. Colors grew more muted, compositions more grounded. Regionalist painters like Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry portrayed American rural life with dignity and restraint. Meanwhile, urban artists like Isabel Bishop and Reginald Marsh focused on the working poor of New York. Their canvases conveyed the chaos and grit of Depression-era streets, offering a stark contrast to the clean geometry of 1920s abstraction.

Artists Facing Hardship

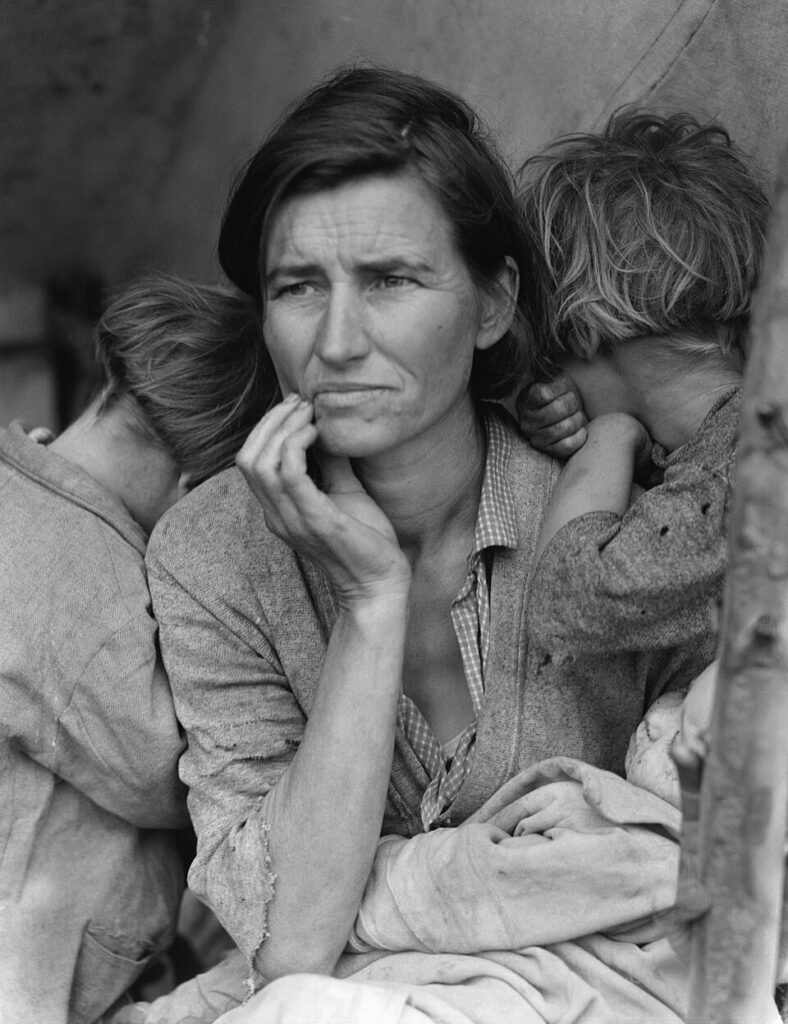

For many artists, the Depression years were marked not only by inspiration but also by deep personal struggle. Dorothea Lange, initially a portrait photographer, began documenting the plight of migrant laborers and displaced families. Her photograph Migrant Mother (1936), taken in Nipomo, California, remains one of the most iconic images of the era. Lange was hired by the Farm Security Administration (FSA), which employed artists and photographers to visually record the impact of government programs and rural hardship.

Walker Evans, another FSA photographer, captured austere images of Southern sharecroppers and abandoned homes. His collaboration with writer James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), became a landmark work blending image and text. Painter Ben Shahn also worked with the FSA, using his background in lithography to create politically charged visual narratives about unemployment and exploitation. These figures helped redefine the role of the artist as both witness and commentator.

Themes in Depression-era art included:

- Family resilience under economic strain

- Industrial labor and mechanization

- Dust Bowl migrations

- Urban poverty and homelessness

- American rural life and tradition

- Faith, community, and moral endurance

The Rise of Art as Protest

The Great Depression spurred a surge of political art, particularly among left-leaning intellectual circles and labor groups. Though most mainstream artworks of the period maintained a patriotic tone, some artists directly critiqued economic systems, class divisions, and government failures. The John Reed Clubs (named after the American journalist who covered the Russian Revolution) supported artists and writers who sought to expose the struggles of the working class through visual media.

Printmaking, in particular, became a vehicle for mass communication and dissent. Artists like Hugo Gellert and William Gropper produced stark lithographs and woodcuts illustrating breadlines, police violence, and slum life. These works often circulated in progressive journals and pamphlets. Though controversial, they were part of a broader trend that saw art used as a tool for advocacy rather than decoration. The Depression blurred the line between political speech and creative expression.

The Federal Government as Patron of the Arts

Origins and Impact of the WPA Federal Art Project

In 1935, as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) launched the Federal Art Project (FAP) to employ artists and make art accessible to all Americans. Holger Cahill, a museum curator and art historian, directed the initiative, overseeing the hiring of more than 10,000 artists during its run. The project extended to nearly every state, with over 100 community art centers established across the country.

Artists were paid an average of $23.86 per week—enough to survive in hard times. Over the life of the project (1935–1943), the FAP supported the creation of over 200,000 works of art, including murals, sculptures, prints, and craftworks. The federal government had never before taken such an active role in promoting the arts. This cultural investment laid the groundwork for how the United States would approach arts funding well into the 20th century.

Murals, Posters, and Community Engagement

Murals were among the most visible and enduring contributions of the FAP. Post offices, schools, hospitals, and other public buildings became canvases for images of American history, agriculture, industry, and community life. These murals were often painted in a realist style, depicting ordinary citizens and regional stories that viewers could relate to. Prominent muralists included Edward Millman, Mitchell Siporin, and Victor Arnautoff.

The WPA’s Poster Division also produced thousands of vibrant, functional designs promoting public health, safety, education, and cultural events. These were not throwaway graphics; many of them were highly stylized, blending Art Deco and folk influences. Community art centers, meanwhile, provided free classes in painting, sculpture, photography, and crafts. For many Americans—especially those in rural areas—this was their first exposure to making or even seeing original art.

Critics, Controversies, and Lasting Legacy

Though popular with the public, the FAP was not without controversy. Some lawmakers and commentators criticized the project as a waste of taxpayer money, while others accused certain artworks of promoting communist ideals. Murals that included workers or industrial themes were especially scrutinized. In some cases, paintings were removed or covered due to political pressure or changes in local opinion. Yet despite these challenges, the FAP earned a broad base of support from civic leaders and educators.

The long-term effects of the program were significant. Many artists who worked under the WPA went on to become leaders in the postwar art world, including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Lee Krasner. Although these artists later embraced abstraction, the Federal Art Project gave them their start and introduced them to the power of art as a public tool. The program also helped shift the narrative of art from being a luxury of the elite to a shared national asset.

Women and Minorities in Federal Art Programs

While the most publicized New Deal artists were often white men, women and minority artists played important roles in WPA projects. Augusta Savage, an African-American sculptor, was appointed director of the Harlem Community Art Center in 1937 and trained an entire generation of Black artists, including Jacob Lawrence and Norman Lewis. Her work, such as Lift Every Voice and Sing (1939), became a touchstone of Black cultural expression.

Latino artists, particularly in the Southwest, also contributed significantly. Xavier Gonzalez, José Cisneros, and others integrated Hispanic history and iconography into public works. Native American artists such as Gerald Nailor and Allan Houser participated in special Indian Division projects, often blending traditional themes with modern styles. Female artists like Lucienne Bloch, Marion Greenwood, and Elizabeth Olds created murals, lithographs, and educational illustrations. While women and minorities faced discrimination and limited access to high-profile commissions, the New Deal offered a rare moment of official inclusion.

Legacy of Depression-Era Art in American Identity

How the 1930s Defined “American Art”

The 1930s reshaped not only what American art looked like but also what it meant. Gone were the days of imitating European trends or chasing elite approval. In their place came a new visual vocabulary rooted in shared national experience—rural life, industrial labor, family hardship, and civic pride. Regionalism and social realism became the visual backbone of American identity, presenting images that Americans recognized and valued.

Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930), John Steuart Curry’s Tornado Over Kansas (1929), and Thomas Hart Benton’s murals for the Missouri State Capitol offered mythic yet grounded visions of the American spirit. These images celebrated strength, order, tradition, and work ethic in a time of disarray. Even as abstract art would later dominate major galleries, the 1930s forged a visual identity that connected Americans across class and geography.

Influence on Postwar Movements

After World War II, many WPA artists transitioned into new movements. Some, like Pollock and Rothko, rejected figurative realism and helped launch Abstract Expressionism. However, their early exposure to public art and civic themes through the WPA remained foundational. This era also seeded the development of postwar social movements in art, including the civil rights mural movements of the 1960s and 1970s, which echoed WPA aesthetics and goals.

The Depression era also influenced later government arts initiatives. When the National Endowment for the Arts was founded in 1965, it drew directly on lessons from the New Deal: federal support could nurture talent, widen access, and make art a national good rather than a coastal luxury. Documentarians, community muralists, and public sculptors in the late 20th century would continue building on this template.

Preservation, Collections, and Modern Recognition

Over time, the artistic legacy of the 1930s has gained renewed attention. Museums such as the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Library of Congress, and the Crystal Bridges Museum have developed extensive collections of Depression-era paintings, prints, and photographs. Academic interest has grown as well, especially in understanding how this era shaped public taste and artistic labor.

Many original murals have been preserved, restored, or rediscovered in post offices, schools, and town halls. Projects in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York have brought hidden or damaged WPA works back to life. Traveling exhibitions, digital archives, and public interest have ensured that the art of the Great Depression remains not just a relic, but a living influence in the American cultural imagination.

Popular Memory and Reassessment in the 21st Century

During the 2008 recession and the economic uncertainty that followed, public interest in the art of the 1930s surged again. Americans turned to this period not just for inspiration, but for proof that hardship can produce cultural richness. Exhibitions such as 1934: A New Deal for Artists (2009) reminded audiences that beauty and meaning can thrive even amid collapse.

The emotional clarity and moral seriousness of Depression-era art continue to resonate today. In a fragmented and digital world, the grounded, hand-made realism of the 1930s feels more relevant than ever. It is a reminder that American identity is not a marketing slogan—it is the face of a mother in a field, a worker in a forge, or a community watching a mural take shape on the side of a post office.

Key Takeaways

- The stock market crash of 1929 destroyed elite patronage systems and forced artists to find new audiences and themes.

- Depression-era art focused on rural life, labor, resilience, and American values, moving away from urban abstraction.

- The Federal Art Project of the WPA employed over 10,000 artists and created more than 200,000 works of public art.

- Artists like Dorothea Lange and Grant Wood became icons by portraying the dignity and hardship of ordinary Americans.

- Depression-era public art continues to shape American cultural memory and inform public art initiatives today.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the WPA Federal Art Project?

A New Deal initiative (1935–1943) that hired thousands of artists to produce murals, prints, sculptures, and teaching programs across the U.S. - Who were key artists during the Great Depression?

Grant Wood, Dorothea Lange, Thomas Hart Benton, Walker Evans, and Ben Shahn were among the most influential. - What artistic movements grew during the Depression?

Social realism and regionalism were dominant, replacing abstract and elite modernist trends. - Where can I see New Deal art today?

Many WPA murals are still visible in public buildings, and major museums like the Smithsonian preserve extensive collections. - How did this era influence American identity?

Depression-era art promoted shared values like hard work, resilience, and national unity—shaping the visual language of American patriotism.