The earliest art made in Hobart was never meant for galleries. It arrived bundled in the toolkits of military engineers, naturalists, cartographers, and administrators—practical men trained to observe with precision, record with accuracy, and embellish when required. Long before oil paintings graced public walls or landscapes were celebrated for their compositional balance, the island’s artistic output was tethered to utility. Hobart’s first artworks weren’t aesthetic luxuries—they were assertions of order.

Drawing Territory: The Sketchbook as Instrument of Control

In 1804, when Lieutenant-Governor David Collins led the first British settlers to the banks of the River Derwent, he was accompanied not only by soldiers and convicts, but also by artists in disguise—surveyors and draughtsmen whose job was to document, not to create. Among them was George William Evans, a deputy surveyor whose sketchbooks, spanning from 1809 to 1812, contain watercolours and ink studies of Hobart’s hinterland. Stored now in the National Library of Australia, these compact drawings mix fidelity with quiet beauty. Trees, hills, rivers—rendered in deliberate lines and soft washes—carried the dual purpose of charting terrain and conveying its promise.

There is a quiet irony to these images. They present a seemingly unpeopled landscape, calm and ready for cultivation, despite the presence of an Indigenous population whose absence in the visual record speaks volumes about the colonial mindset. But that absence was visual, not ideological. The point of these sketches was not to witness complexity, but to reduce it—to translate the unruly into something surveyable, ownable.

Major Thomas Scott’s 1824 Chart of Van Diemen’s Land, a delicately hand-coloured engraved map, takes this logic even further. More than a geographic tool, it serves as a form of proto-art, where colour and line are deployed to domesticate and aestheticize. The sea is painted a uniform blue; forests are stylised as textured green swaths. The map doesn’t just locate Hobart—it frames it, preparing it for the civilising project.

Watercolour and Weather: Hobart Town from the New Wharf

As the colony stabilized, the art shifted. By the 1850s, Hobart had grown from outpost to town, and artists began to treat it as a subject rather than an obstacle. In 1857, Henry Gritten painted Hobart Town from the New Wharf, a panoramic watercolour that shows the harbour as both working port and picturesque subject. The image is calm, richly detailed, and notably polished. It belongs to a genre of colonial painting designed to reassure viewers—whether locals or audiences back in England—that civilisation had taken root.

Gritten, who arrived in Australia in the early 1850s after exhibiting at the Royal Academy in London, brought with him a European eye. In Hobart Town from the New Wharf, buildings are neat, ships glide effortlessly across the bay, and the mountains loom softly in the background. Gone are the jagged lines and hasty marks of the early surveyors. In their place is a language of settled beauty.

But beneath the surface, the image also speaks of aspiration. The town, carefully rendered with civic pride, looks north toward the future—toward commerce, expansion, and self-definition. The painting, housed today in the State Library of Tasmania, is more than a record; it is a proposition.

Civilising with Canvas: Taste, Virtue, and the Early Collectors

In the early decades of the 19th century, Hobart was a rough-edged town where culture had to be imported. Convict artists, skilled in signwriting or decorative carving, sometimes found themselves drafted into more ambitious commissions—church murals, architectural embellishments, even early portraiture. But formal art collecting remained in the hands of administrators, clergy, and retired officers. These were men who had brought watercolours in their trunks or ordered prints from London catalogues.

Colonial governors like Sir John Franklin—himself a cultivated figure with a deep interest in science and the arts—saw the promotion of visual culture as a tool of moral uplift. In 1843, Franklin and his wife Jane established the Lady Franklin Museum (also known as Ancanthe), a small Greek-revival structure just outside Hobart designed to house art, books, and ethnographic materials. Though short-lived in its initial phase, the building remains a symbol of the colony’s early ambition to foster civic refinement through art.

The institution that would eventually become the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) began as a similarly mixed project—part science, part curiosity cabinet, part gallery. Its early acquisitions were eclectic: specimens, artefacts, oil portraits, and geological samples. Yet the very presence of a permanent building devoted to visual and material culture marked a key step in Hobart’s transformation from penal settlement to cultural settlement.

Convict Artisans and Quiet Builders of Culture

Among the least acknowledged figures in this phase of Hobart’s art history are the convict artisans—skilled tradesmen sentenced for forgery, theft, or other crimes of survival. Many had prior training as engravers, illustrators, or decorators. Their anonymous contributions live on in church fittings, carved sandstone façades, and hand-painted signs. One can still find examples of their work embedded in Hobart’s built fabric—mute but enduring.

Their art, if it can be called that, was usually functional, and rarely signed. Yet it helped seed an aesthetic consciousness rooted not in theory but in practice. Here was a city being built with hands accustomed to ornament, proportion, and pattern. In their own way, these makers laid down an invisible but lasting foundation for Hobart’s visual future.

- A stonemason’s flourish on a church lintel.

- A painted panel above a shopfront, surviving more than a century.

- The layout of a garden, symmetrical and quiet.

These traces whisper beneath the grander stories of Glover or Gritten, but they remain—weathered, partial, and instructive.

A City Looking Outward and Inward

By the mid-19th century, Hobart was no longer just a receptacle for orders from London—it had begun to generate its own aesthetic language. Artists, both amateur and professional, found in the Tasmanian light a clarity that invited slow looking. Hills, bays, and weather became more than topography; they became mood, atmosphere, even metaphor.

But for now, the art remained framed by European conventions. The sublime and picturesque guided composition. English tastes shaped public reception. And yet something else had begun to stir. A certain spatial quietness. A concern with distance. An attention to weather that went beyond description. The foundations were laid—not just in stone and sketch, but in vision.

The river, always central, reflected not just the sky but the colonial project itself: a shimmering surface over deep and shifting currents. Hobart’s early art, like its city plan, looked both out to sea and back to the mountains. It carried ambition, uncertainty, and a surprising delicacy—waiting for the first great painter to arrive.

Chapter 2: The Watercolour Age – Romanticism in a Remote Colony

John Glover stepped ashore in Van Diemen’s Land in February 1831 with a suitcase full of brushes and a reputation already secured. He was 64, a veteran of the Royal Academy exhibitions in London, and one of the finest landscape painters of his generation. He had painted the English countryside into careful, luminous order; now he arrived at the far end of the world, armed with a Romantic eye and a gentleman’s self-possession, to paint something utterly unfamiliar. Hobart—then a remote town on the edge of empire—was about to see landscape painting redefined by an artist unburdened by ambition, yet still guided by a lifelong pursuit of beauty.

The Mills Plains Vision: Pastoral Order in an Unruly Land

Glover did not settle in Hobart but moved northward to Mills Plains near Deddington, where he acquired a tract of land that offered sweeping views, quiet pastures, and just enough wilderness to keep the eye engaged. There, from the veranda of his homestead, he began the most original phase of his career. What he painted was not wilderness in the raw, but wilderness domesticated. View of Mills Plains, Van Diemen’s Land (c.1833), held by the National Gallery of Victoria, is a gently ordered composition: open meadows, eucalypts spaced with improbable regularity, distant hills softened into blue. The foreground is studiously Arcadian. Grazing cattle provide scale; trees are shaped more like elms than gums. The light is golden, but never harsh.

At first glance, it seems as though Glover brought England with him. But something in the image resists. The trees, despite their placement, retain their local identity: thin-trunked, twisted, silver-grey in a way no English oak could mimic. The sky is clearer than Turner ever imagined. And the mountains in the background, though quietly resting, are Tasmanian in bulk and presence.

What Glover did was not transplant Europe onto Australia but fuse the two into a hybrid that served both memory and observation. He painted what he saw, certainly—but he also painted what he wanted to believe: that Van Diemen’s Land could become a pastoral Eden.

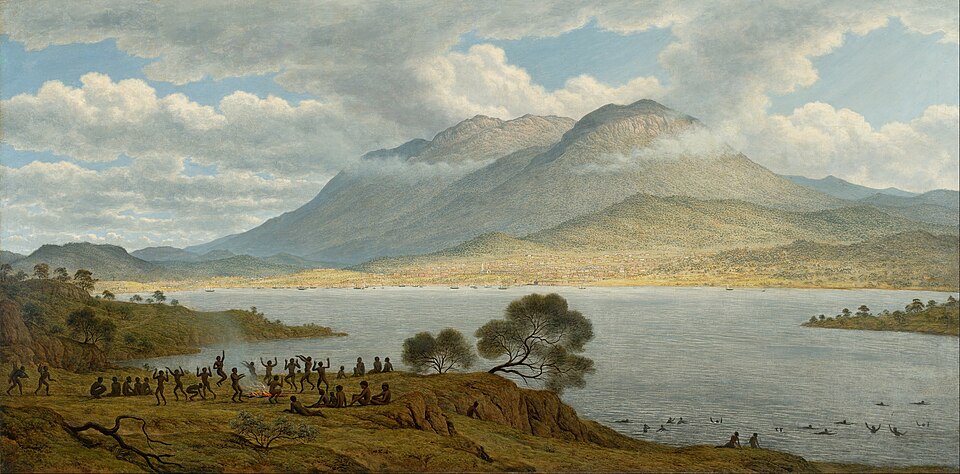

From Sublime to Familiar: Mount Wellington Recast

In Mount Wellington and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point (1834), housed in the Art Gallery of South Australia, Glover turned his eye toward the capital. Here, Hobart appears nestled beneath the looming silhouette of Mount Wellington, the city’s geometry softened by distance and bathed in gentle light. The river, calm and almost glassy, stretches between the foreground’s tree-fringed bank and the receding sprawl of buildings and wharves. This is not the Romantic sublime of alpine terror or brooding weather—it is sublimity reined in, domesticated, and made picturesque.

What makes this image extraordinary is its refusal to dramatize. Glover’s Mount Wellington is not a wild frontier but a steady anchor. His treatment of the light is more Mediterranean than Antarctic; the sky speaks of mildness, not menace. By this point, Glover was no longer painting Australia as an outsider. He was interpreting it with the confidence of a settler who had begun to understand not only the physical terrain but its visual logic.

Glover’s Trees: The Problem of the Gum

One of Glover’s greatest challenges—and ultimately his most significant innovation—was the eucalyptus tree. European landscape traditions were grounded in oak, elm, beech—trees with spreading canopies and symmetrical mass. The Tasmanian gum defied these ideals. It grew tall and angular, its bark peeling, its foliage sparse and tattered. It cast strange shadows and lacked the volume that European painters relied on for compositional weight.

Early colonial artists often fudged the problem, rendering eucalypts as generic trees or avoiding them altogether. Glover, by contrast, confronted them directly. His 1830s Tasmanian works are the first to truly depict gum trees as they are: with silvery trunks, fragmentary crowns, and a kind of spatial openness that challenged European depth perception.

This was not just a technical achievement—it was a cultural turning point. Glover’s trees marked the beginning of a visual vocabulary appropriate to place. They signalled that Tasmania could be painted on its own terms.

The Romantic Mind in Exile

Despite his clear-sighted observation, Glover remained a Romantic at heart. His Tasmania was never just descriptive—it was aspirational. In choosing to settle and paint in Van Diemen’s Land, he found the perfect synthesis of distance and dream. Here, far from the salons of London, he could paint without competition, publish without critics, and depict a world that had not yet been fully claimed.

Yet his isolation was not complete. Glover continued to exhibit via correspondence and sent works to England for sale. He maintained correspondence with his sons, both of whom were active in colonial affairs, and he carefully curated his public image as the elder statesman of Tasmanian art. He was not forgotten—he was, in many ways, more visible than ever.

And yet, there was something in his Tasmanian canvases that went beyond calculation. In their stillness and light, one senses a kind of peace. Glover, unlike the convicts or the administrators, had chosen exile. His art reflects that voluntary distance—a clarity of view made possible only by leaving the familiar behind.

The End of the Beginning

By the time of Glover’s death in 1849, Hobart’s art world remained modest but indelibly changed. No longer merely a town of surveyors and sketchbooks, it had hosted—if only for a decade—a painter of European stature who treated its landscapes with dignity and style. Glover did not found a school or build an institution. But he left behind a new standard, a new way of seeing, and a body of work that reframed Tasmania not as a place to be endured, but as a place to be painted.

It was the beginning of a local Romanticism: gentler than its European counterpart, less haunted by history, and deeply tied to the rhythms of light, weather, and space. Glover, in the end, didn’t transplant Europe. He translated it—and in doing so, gave Hobart its first mature artistic voice.

Chapter 3: Gentlemen Amateurs and Drawing Rooms

In the parlor corners and club rooms of early Hobart, long before the rise of professional galleries or trained critics, art found its way by quieter routes—through portfolios unwrapped after supper, lithographs pinned inside drawing rooms, and amateur sketches exchanged over port. This was an age of cultural cultivation without an art market, where connoisseurship and creativity were exercised in private spaces and social rituals. It was also, paradoxically, a time when the seeds of Tasmania’s public visual culture were first planted—not by professionals, but by well-read enthusiasts, society women with taste, and Anglican clerics with collections.

Drawing as Pastime and Politeness

In the absence of formal art schools or exhibition circuits, the Hobart of the mid-19th century relied on self-made artists and informal instruction. Drawing, watercolouring, and even rudimentary etching were considered suitable pursuits for the educated classes—particularly for gentlemen of leisure and women of social standing. A good sketch was a mark of cultivation; a portfolio of travel views, a sign of refinement.

The drawing room was not just where pictures were shown—it was where they were made. Many early settlers brought with them the tools of genteel sketching: graphite sets, ivory palettes, fine brushes imported from England. Instruction manuals such as The Young Ladies’ Drawing Book or Sketches from Nature circulated among Hobart households. The results—fragile landscapes, precise botanical studies, copied engravings—were often stored away, but sometimes framed and displayed.

This was a culture of amateurs in the purest sense: those who made art for love, not livelihood. And within these modest beginnings, a civic appetite for visual pleasure began to stir.

The Mechanics’ Institute and the Public Eye

By 1827, Hobart’s growing middle class had begun to formalize its cultural ambitions. That year saw the founding of the Hobart Town Mechanics’ Institute—one of the earliest in Australia—dedicated to education, lectures, and the improvement of public taste. Although its initial focus was scientific and literary, it quickly expanded to include exhibitions and displays of visual material: maps, drawings, scientific illustrations, and, increasingly, landscape views.

The Institute offered evening lectures on art, natural history, and architecture. These talks, often illustrated with diagrams or prints, were attended by clerks, shopkeepers, teachers, and tradesmen—many of whom could never afford original paintings but could now encounter perspective, proportion, and style in the form of education.

In an 1830s lecture series, one speaker reportedly traced the lineage of landscape painting from Claude Lorrain to John Glover, connecting the old masters of Europe with the new interpretations appearing on Tasmanian soil. This intellectual framework, though modest in scale, gave Hobartians a vocabulary with which to discuss and appreciate visual art—a crucial development for a society still defining its identity.

Lady Franklin’s Temple: Ancanthe and Its Ideals

If the Mechanics’ Institute spoke to the city’s aspiring bourgeoisie, the Lady Franklin Museum—built in 1842–43 on a hill outside Hobart—embodied a more aristocratic vision of cultural uplift. Commissioned by Lady Jane Franklin, wife of the colonial governor, and designed by surveyor John Sprent, the small Greek-revival structure was meant to house paintings, natural history specimens, and curiosities from across the empire. Lady Franklin, a formidable figure with literary and scientific interests, called it “Ancanthe”—from the Greek, meaning “blooming valley.”

The museum, though short-lived in its original purpose, became one of Hobart’s earliest public spaces devoted to the visual arts. Visitors might encounter shell collections next to oil portraits, or lithographs from India displayed beside Tasmanian geological samples. It was eclectic, certainly—but also sincere in its ambitions.

Ancanthe’s significance lay not in its size or contents but in its symbolism. Here was an institution, however small, built explicitly for art in a town better known for its penal system and merchant shipping. It suggested that taste, virtue, and visual contemplation could find a home even on the colonial periphery.

John Skinner Prout and the Colonial City Scene

Between 1844 and 1848, the English artist John Skinner Prout toured the Australian colonies, including a productive period in Hobart. Unlike Glover, who painted bucolic visions of rural Tasmania, Prout turned his attention to urban life. His sketches and lithographs—some of which survive in the National Library of Australia—depict Hobart’s narrow streets, its convict-built stone buildings, and the bustle of markets and docks.

One image, Elizabeth Street, Hobart Town, shows townspeople mingling near wooden carts, while sandstone façades rise behind them. It is not idealised. The gutters are muddy, the figures loosely drawn, the perspective slightly skewed. Yet there is vitality in the scene—a sense of immediacy that would have resonated with Hobartians seeing their own city on paper.

Prout also held public exhibitions during his stay, including demonstrations of lithographic printing. These events, advertised in local newspapers, helped demystify the artist’s process and encouraged local amateurs to take their own work more seriously. His presence offered a model: the itinerant artist as both craftsman and showman.

The First Art Union: Subscription, Chance, and Public Taste

By 1858, Hobart hosted its first Art Union exhibition—a curious hybrid of exhibition, lottery, and public taste-making. Subscribers paid a small fee, which contributed to the purchase of artworks. At the end of the exhibition, winners were drawn by lot and allowed to choose a painting from among those displayed.

The model, imported from Britain, served several purposes. It rewarded artists financially, encouraged collecting among the middle classes, and gave the public a reason to engage directly with visual art. In Hobart, the Art Union offered modest landscapes, still lifes, and portraits—many produced by self-taught painters. Reviews from The Mercury praised the quality of the entries while calling for more ambitious subjects and stronger technique.

Though the works were uneven, the event marked a turning point. Art was no longer confined to the drawing room or the museum-in-miniature. It had entered the realm of public entertainment and civic pride.

Taste Before Institutions

Before there was a gallery in Hobart, there was taste. It expressed itself in conversation, in scrapbooks, in sketching clubs and informal critiques. The city’s early art history is not defined by masterpieces or manifestos, but by the slow accumulation of habits: the way people looked, the things they framed, the images they discussed.

This period laid the groundwork for later professionalism. It introduced the idea that art could belong to the city, not just the individual. And it proved that even in a penal colony, amid hardship and improvisation, there was room for drawing—not just as pastime, but as a means of making sense of place.

Chapter 4: From Illustration to Institution – Founding the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

When Hobart began to consider itself more than a penal outpost—when it sought to gather, display, and preserve the things it had inherited and made—it did so not through a single stroke of civic ambition, but through the gradual stitching together of rooms, societies, collections, and public trust. The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) stands today as one of the oldest combined museums and galleries in Australia, but its origins lie in an age before the very idea of public culture was secure.

Cabinets and Cases: The Age of Collecting

The earliest collectors in Hobart were not curators. They were botanists, geologists, naval officers, and amateur naturalists who kept private rooms full of pinned insects, labelled minerals, shell specimens, and drawings made in the field. Some of these men belonged to informal scientific circles. Others simply saw it as a gentlemanly obligation to study and catalogue the strange environment around them. Their collections were personal but rarely selfish; they were meant to instruct, to civilise, to uplift.

By the 1830s, there were calls for a shared institution that might house these objects. It was not art that prompted the demand, but science. The collections of shells, rocks, taxidermied birds, and botanical samples were increasing. There was no permanent structure, and only intermittent access to public viewing. Those who donated specimens wanted them to be seen and preserved. A city with a customs house, gaol, and Supreme Court ought to have a museum as well.

The Royal Society and a Formal Beginning

The turning point came in 1843 with the founding of the Royal Society of Tasmania, the oldest such society outside Britain. Modeled on the Royal Society of London, its aim was to promote scientific and intellectual inquiry in the colony. Under its stewardship, the effort to create a permanent museum gathered pace. The Society inherited a number of private collections and began to assemble them into a coherent whole.

By 1848, the Society had formally established the Tasmanian Museum as a public institution. At first, it was limited in scope and space. The collections were housed in temporary quarters and displayed with little sense of hierarchy. Skulls sat beside ship models. Portraits shared space with fossilised wood. But it was a beginning—a signal that Hobart was ready to take itself seriously as a cultural city.

Lady Franklin’s Vision Recast

Five years earlier, in 1843, Lady Jane Franklin had commissioned a small neo-classical building on the slopes of Mount Nelson. Known as Ancanthe, it was intended as a “temple of the arts,” a place where Tasmanian culture could be preserved and nurtured. Paintings, books, scientific objects, and local crafts were housed there, albeit sporadically and without a full-time curator. Although her vision was never fully realised, Ancanthe became part of Hobart’s broader cultural scaffolding.

By the mid-1850s, many of the items from Ancanthe were transferred to the museum in town, adding to its growing identity as both repository and exhibition space. The ideal of combining art with science, image with object, was no longer confined to eccentric patrons or private libraries—it had moved into the centre of Hobart’s civic life.

A Permanent Building and an Expanding Mission

In 1861, the Tasmanian government allocated land for a dedicated museum building on the corner of Argyle and Macquarie Streets. Designed by architect Henry Hunter and completed in 1862, the structure was modest but dignified, providing a permanent home for the collections that had until then wandered between venues. An inaugural exhibition was held that same year to raise funds for furnishings, attracting wide public attention and critical praise.

The building was located beside one of the oldest surviving structures in Hobart—the Commissariat Store, built between 1808 and 1810—which would later be incorporated into the museum complex. Over time, new wings were added, expanding both the footprint and the ambition of the institution. By the end of the 19th century, the museum was not just a place of storage but of interpretation. It offered exhibitions, lectures, and educational displays that made it central to the city’s intellectual life.

Art Enters the Frame

Although natural history dominated the museum’s early decades, visual art began to claim a larger role. Colonial landscape paintings, portraits of governors, and early sketches of Hobart found their way into the collection. These were not always treated as high art; often, they were valued for their documentary quality. A painting of Mount Wellington was appreciated not for its brushwork but for its accuracy. Yet over time, aesthetic judgment deepened.

By the 1880s, the art holdings had grown enough to warrant independent attention. In 1885, the governance of the museum passed from the Royal Society to a board of trustees established under state authority, and with this came the formal incorporation of an “art gallery” function. Paintings were no longer side exhibits. They were central.

Donations from private collectors, acquisitions funded by public subscription, and state-sponsored purchases expanded the gallery’s offerings. Early Tasmanian works by John Glover and William Charles Piguenit, alongside portraiture and European prints, were exhibited not as decoration but as cultural heritage.

The Institution as Inheritance

The significance of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery lies not in the size of its collection but in its role as Hobart’s first true cultural institution. It brought together science, history, and visual art in a single civic project. It trained the public eye. It created a home for Tasmanian stories in physical form.

Its architecture—part colonial warehouse, part neoclassical museum—mirrors the hybrid nature of its mission. It is both archive and gallery, both historical witness and living space. Generations of schoolchildren, amateur artists, and curious visitors have walked through its doors, encountering paintings beside skulls, colonial tools beside oil portraits.

And through that long accretion of displays, donations, and quiet scholarship, Hobart slowly became a city that not only produced art, but knew how to keep it.

Chapter 5: Quiet Realists – 19th Century Tasmanian Painting

In the second half of the 19th century, Hobart’s art scene turned inward. Gone were the grand romantic gestures of John Glover or the picturesque sentimentality of early colonial views. What emerged instead was a quieter school of painting: artists who observed closely, who rendered their subjects with restraint, and who worked more often in solitude than in salons. Their realism was not doctrinaire—it had no manifestos—but it was deliberate. These painters sought accuracy not only of appearance but of mood, and in doing so, they laid the groundwork for a distinctly Tasmanian sensibility.

William Charles Piguenit and the Art of Atmosphere

No figure better exemplifies this shift than William Charles Piguenit. Born in Hobart in 1836 to a convict-turned-public-servant father and a schoolmistress mother, Piguenit was the first professional painter born in Tasmania, and among the first Australian-born artists to achieve national recognition. His work departed from both the scientific topography of early surveyor-artists and the European nostalgia of immigrant painters. Piguenit’s landscapes were realist in approach but poetic in intent—carefully constructed compositions that aimed to capture not just place, but presence.

His 1875 painting Mount Olympus, Lake St Clair, Tasmania, source of the Derwent marked a breakthrough. Purchased by public subscription for the Art Gallery of New South Wales, it was one of the earliest works by a locally born artist to enter a major public collection. The painting is brooding and vast: a still lake under a heavy sky, distant peaks emerging from a soft mist, the water’s surface catching dim light. The scene avoids melodrama. Its power lies in its balance—between clarity and obscurity, form and dissolution.

Piguenit was a walker. He travelled deep into Tasmania’s interior with sketchbooks, staying for days in alpine regions that were, at the time, largely unmapped and inaccessible. These journeys resulted in a series of oils throughout the 1870s and 1880s that portray the Tasmanian highlands with increasing confidence: Lake St Clair with Mount Ida, View on the Derwent, and others that show not only painterly skill but a growing sense of artistic identity. His light was always local. His clouds had weight. And his silence—his refusal of embellishment—marked a new kind of visual authority.

Bock and the Human Image

While Piguenit turned to the wilderness, Thomas Bock turned his attention to faces. Born in England and transported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1824 for forgery, Bock became one of the colony’s first professional portraitists. By the 1840s, he had established a thriving studio in Hobart, painting likenesses of colonial officials, merchants, and their families. His portraits are restrained and often formal, but they possess a quiet psychological charge. The eyes in a Bock portrait never drift. They hold the viewer with an intensity that belies their polite setting.

Though Bock died in 1855, his influence extended into the decades that followed. His combination of technical finesse and observational seriousness helped shape the expectations of portraiture in Tasmania, where ostentation was frowned upon and likeness was everything. In his work, one finds none of the exoticism or fantasy that characterised some colonial artists’ depictions. His subjects are grounded, dignified, and unembellished.

Portraiture in Hobart remained a largely private affair throughout the 19th century—commissioned for families, officers, or institutional settings. But Bock’s approach set a tone: accuracy over allegory, restraint over flourish.

Realism by Necessity

Hobart’s painters in the latter 19th century often worked in conditions that discouraged excess. There were few buyers, no professional art dealers, and limited exhibition opportunities. Paintings had to justify their presence. For many artists, realism was not a philosophical stance—it was a necessity. They painted what was around them because it was what they knew, and because invention cost more than observation.

This austerity had its own rewards. The small paintings that survive from this period—modest oils of streetscapes, coastal scenes, or interior rooms—are often quietly luminous. Their scale encourages intimacy. Their detail rewards patience. One senses that many were painted in the hours after work, or on Sundays, when time permitted but materials were scarce.

Among the less celebrated but no less significant figures of this era were local painters whose works rarely left Tasmania: minor portraitists, botanical illustrators, skilled copyists, and women who painted within domestic settings and informal circles. Much of their work survives in private collections or regional archives—unsigned, undated, but unmistakably local in palette and subject.

- A small oil of the Huon River, brush marks tight and still.

- A pastel of a child’s face, slightly smudged but attentive.

- A view of Battery Point rendered in dusk tones, the buildings quiet and unsentimental.

These works do not proclaim themselves. They wait to be seen.

Lily Allport and the Edge of Modernity

One painter who emerged near the end of this realist phase was Lily Allport, born in Hobart in 1860. Trained in London and later exhibiting at the Royal Academy, Allport combined technical refinement with a sensitive eye for detail. Her early works, including watercolours and pastels made in Tasmania before her extended stays in Europe, demonstrate the lingering influence of 19th-century realism even as they hint at the looser, more expressive styles that would come in the 20th.

Allport was especially skilled in depicting faces and hands—her portraits retain the psychological stillness characteristic of the Tasmanian tradition, but with a lighter touch. In her drawings, one can sense the boundary between the realist school and the modern. She marks a transition point—not away from realism, but toward a realism more concerned with impression than with exactitude.

Her later work in printmaking would take her further into stylistic experimentation, but her early Tasmanian output belongs to the same quiet lineage as Piguenit and Bock: restrained, skilled, and alert to the subtleties of mood.

The Legacy of Restraint

By the end of the 19th century, Hobart had developed a visual culture that was modest but coherent. The dominant voices were not those of revolution or innovation, but of careful attention. These artists had no manifesto. They made no schools. But they left behind an archive of observation—a record of how Tasmania looked, and felt, before the arrival of spectacle.

Their realism was not merely stylistic. It was ethical. It emerged from patience, from attentiveness, and from the belief that the world, rendered truly, was enough.

Chapter 6: Arts and Crafts to Modernism – Twentieth Century Shifts

The twentieth century arrived slowly in Hobart. Its passage into the arts was not marked by manifestos or movements but by education—deliberate, structured, and steady. While cities like Melbourne and Sydney wrestled with European modernism in public forums and polemical journals, Hobart’s transformation came through classrooms, workshops, and the quiet persistence of teachers. The transition from Victorian aesthetics to modernist possibility did not happen in a moment; it happened across decades, in schools and studios where tradition was not discarded, but gradually reinterpreted.

The School That Shaped a Century

In the early 1900s, the most important engine of Hobart’s artistic development was not a gallery, but an institution: the Hobart Technical College. Founded in the late nineteenth century and expanding in scope after Federation, it became Tasmania’s premier centre for applied arts education. Here, students learned drawing, design, painting, woodcarving, and metalwork—not as abstract ideals, but as practical skills. The curriculum was grounded in the British Arts and Crafts ethos, which stressed craftsmanship, integrity of materials, and technical discipline.

The College’s transformation into a serious art institution was largely the work of Lucien Dechaineux, a Belgian-born artist who arrived in Tasmania in 1907. Educated in Europe, Dechaineux brought with him not only technical excellence but a belief in the dignity of applied art. For over three decades, he taught and served as principal of the College’s art department, shaping generations of Tasmanian artists and designers. He did not lecture from a distance; he demonstrated. His influence was not ideological—it was visual, material, and deeply methodical.

Dechaineux’s presence marked a shift in Hobart’s cultural identity. Under his guidance, students were trained in life drawing, printmaking, watercolour, and composition, as well as design for ceramics, textiles, and furniture. In this environment, the division between “fine” and “decorative” art was blurred, if not irrelevant. This was not an art world in thrall to avant-garde posturing. It was rooted in patience, skill, and making things well.

Violet Vimpany and the Rise of the Independent Studio

Among Dechaineux’s notable students was Violet Vimpany, a painter and printmaker born in Hobart in 1886. Trained at the Technical College, Vimpany emerged as one of the city’s most visible working artists during the interwar period. She maintained an independent studio, exhibited regularly, and taught privately. Her etchings and paintings reveal a balance between traditional draftsmanship and a modern sensitivity to composition and negative space.

Vimpany’s work was neither provincial nor programmatic. Her subjects—Tasmanian hillsides, fig trees, domestic interiors—are treated with a firmness of line and a subtle tonal range that reflect both Arts and Crafts discipline and the creeping influence of modern European print aesthetics. While her name never reached national prominence, she was central to Hobart’s art circles. She taught, exhibited, and quietly extended the vocabulary of Tasmanian realism into something leaner and more composed.

Like many artists of her generation, Vimpany worked without fanfare. She had no movement behind her, no gallery representation in Sydney, and little critical attention beyond Tasmania. Yet her career reflects the quiet infrastructure of Hobart’s art scene in the early 20th century: solitary dedication, community respect, and a body of work rooted in a deep familiarity with place.

Teaching Modernism Gently

By the 1930s, the influence of European modernism—filtered through magazines, touring exhibitions, and returning travellers—began to register more clearly in Hobart’s art schools. But it did so without rupture. The transition from Arts and Crafts to modernist abstraction came not through rebellion, but through adaptation.

Dorothy Stoner, born in 1904, trained at the Hobart Technical College under Dechaineux and later Mildred Lovett. Stoner would go on to become one of Tasmania’s most distinctive modernist painters, but her early work shows the same disciplined roots as her mentors. Her pastels, in particular, combine delicacy with structural rigour—figures and still lifes that float between realism and stylisation, always grounded in sound draftsmanship.

Stoner’s teaching career was as important as her painting. From the 1940s onward, she became a central figure at the very institution where she had trained. She instructed students not in slogans or manifestos, but in colour theory, observational accuracy, and careful composition. Her version of modernism was incremental, textural, and interior—a modernism born not from rupture, but from careful refinement of what had come before.

The Art Society as Platform

While the Technical College trained artists, the Art Society of Tasmania provided the platform for them to be seen. Founded in the late 19th century, the Society remained active well into the 20th, organising exhibitions and offering artists a venue to display and sell their work. In the decades before a full public gallery system took hold, the Society’s annual shows were the primary venue for public artistic engagement in Hobart.

These exhibitions featured a mixture of academic landscape painting, Arts and Crafts–inspired decorative work, and, gradually, more experimental forms. The Society was conservative in its curation, but it allowed for stylistic evolution. Artists like Stoner, Vimpany, and their students could test new ideas within a familiar framework. There was no modernist schism—only a slow reorientation of taste, shaped by the work itself.

The exhibitions were also social events, attended by teachers, clergy, businesspeople, and amateur collectors. Hobart’s art world, small as it was, existed in layers: studio, classroom, exhibition, home. Sales were modest, reviews limited, but reputations were made, and a local art economy—fragile but real—emerged.

- Paintings bought for school prizes or wedding gifts.

- Etchings sold at fundraising auctions for churches or hospitals.

- Watercolours commissioned to record homes, gardens, or familiar landscapes.

This was art made to be lived with, not theorised.

Between Styles, Between Worlds

The Tasmanian art of this period defies easy categorisation. It is not provincial in the pejorative sense, nor is it cosmopolitan in ambition. Rather, it reflects a culture that valued skill over fashion, substance over noise. The shift from 19th-century realism to 20th-century modernism did not come through rejection, but continuity. The drawing skills taught in the 1910s shaped the abstract explorations of the 1950s. The decorative sensibility of the Arts and Crafts movement influenced the structure of mid-century Tasmanian abstraction. The past was not cleared away—it was absorbed.

That Hobart moved more slowly than other Australian centres was not a weakness. It allowed a continuity of purpose and technique that would, in time, support a new generation of artists less concerned with external validation and more interested in their own vision. The city’s relative isolation forced its painters and printmakers to refine their craft, not their careers.

They were not part of a school. They belonged to a place.

Chapter 7: Tasmanian Moderns – Between Isolation and Innovation

In mid-20th-century Hobart, modernism arrived quietly. There were no manifestos, no raucous break with the past, no sudden wave of imported style. What developed instead was a modernism of temperament—rooted in observation, shaped by strong local teaching, and moderated by the realities of working in a small, geographically isolated city. Artists experimented not because they wanted to reject tradition, but because they had absorbed it so completely that they could move beyond it. This was not revolution; it was refinement.

A Local Modernism, Slowly Cultivated

The artists who defined Hobart’s modernist turn had been trained in drawing, tonal control, and careful composition. Their early work often bore the marks of Arts and Crafts discipline or academic realism. But over time, they allowed looseness to enter. Colour became more expressive. Forms softened or dissolved. The subject was no longer always central; sometimes it was the arrangement of shapes, the play of planes, or the energy of the brushwork itself that held attention.

Edith Holmes was one of the first to push against the boundaries of older styles. Born in Tasmania in 1893 and trained first in Hobart and later in Sydney, Holmes returned to the island with a broader visual vocabulary and an eye attuned to modernist structure. Her paintings are rich in colour but never garish, and her forms—especially in portraiture and still life—show an intuitive balance between clarity and abstraction. She painted persistently, exhibited regularly, and became a quiet cornerstone of the local art world through the 1930s to the 1960s.

Dorothy Stoner, a slightly younger contemporary, brought a sharper, more graphic sensibility. Her use of pastel, especially in figurative work, introduced a stylised economy that hinted at European influences but remained distinctly local in its palette and tone. Stoner had been a student at Hobart Technical College before teaching there herself, and her influence stretched far beyond her own practice. She helped shape the expectations of modern art in Hobart: that it could be disciplined without being stiff, expressive without being chaotic.

Jack Carington Smith and the Studio as Institution

If Holmes and Stoner embodied the studio artist, Jack Carington Smith brought institutional momentum to modernism. Born in Launceston in 1908, he studied art both in Australia and in London, returning to Tasmania with strong academic credentials and a deep commitment to teaching. In the 1940s he became head of the art department at Hobart Technical College and later, as the school evolved into the Tasmanian School of Art under the University of Tasmania, he remained its guiding figure.

Carington Smith was a technical master with a modern eye. His own paintings moved between mural-scaled compositions, sensitive portraits, and stylised studies of form. He was not radical in subject or technique, but he introduced students to ideas of abstraction, compositional dynamism, and the emotional potential of colour and design. Perhaps his greatest achievement was not his own work, but the environment he created: a rigorous, supportive, intellectually serious art school where students were trained in fundamentals and encouraged to develop independent voices.

It was under his leadership that Hobart’s art community matured. The School of Art became a gravitational centre. Students came from around the state, and occasionally from the mainland, to study in a setting that was both technically demanding and creatively open. The divide between modern and traditional began to blur—not in a muddle, but in a synthesis.

Hobart’s Geography as Influence

Tasmania’s physical isolation, so often seen as a limitation, became part of what shaped its modernism. Artists worked without the distractions of fashion. They had to dig into the material world around them—the angled roofs of Hobart’s older houses, the long shadows of winter light, the folding hills outside the city, the river’s changing moods. These elements crept into the structure of their work, not always explicitly, but in atmosphere, tone, and visual rhythm.

This quiet modernism was not parochial. It was introspective. It did not mimic Sydney or Melbourne. Nor did it need to. The painters and teachers working in Hobart through the middle decades of the 20th century understood that art did not need to shout to be new. It could observe. It could study. It could evolve without ceremony.

Carington Smith’s own students would go on to form the backbone of the next generation. They learned to paint light with economy, to draw with accuracy, and to compose with intelligence. Some would remain in Tasmania. Others would travel. But the discipline remained.

The Institutional Turn

The 1950s and 60s also saw important shifts in how art was shown and supported in Hobart. The Art Society of Tasmania continued to mount regular exhibitions, offering a public platform for emerging and established artists alike. But institutional support was growing. The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery began to acquire modern work. Art entered not only private homes but public memory. Critics began to write—if sparingly—and exhibitions travelled.

For the first time, Hobart artists began to feel connected to a larger conversation, even if loosely. Catalogues were read. Paintings were discussed. Debates about abstraction, expression, and technique took place not in cafés or manifestos, but in classrooms, studios, and after exhibition openings. It was a small scene, but it was dense with knowledge.

- A student reworking a drawing after a critique with Stoner.

- A visitor standing silently in front of a new painting by Holmes.

- A Carington Smith mural observed by schoolchildren learning to look, not just to see.

These moments mattered. They formed the bones of a local culture that respected the modern not as fashion, but as a way of paying attention.

Not a Movement, But a Milestone

The artists of this generation did not form a group or give themselves a name. There were no declarations or public schisms. Their modernism was personal and procedural—something grown from years of teaching, looking, and painting. They marked a passage, not a rupture. A moment when Hobart no longer needed to import its vision, because it had grown its own.

In their restraint, they found authority. In their discipline, they found freedom. And in the space between realism and abstraction, they carved out a visual language that was neither derivative nor defensive. It was Tasmanian. It was modern. And it still speaks.

Chapter 8: The Landscape Reimagined – Wilderness, Light, and Scale

In Tasmania, the land always resists simplification. Its sharp ridges, tangled forests, and heavy skies have defied both scientific survey and aesthetic sentimentality. Where early colonial artists tried to tame it with symmetry, and realist painters rendered it with accuracy, the late 20th century brought a different response: a recognition that this land was not a backdrop but a subject—dense, vast, and ambiguous. Painters now approached the Tasmanian wilderness not as scenery to be recorded, but as a force to be reckoned with. What emerged was a landscape art that was muscular, expressive, and deeply local.

Max Angus and the Watercolour Wilderness

No artist did more to reinvigorate Tasmanian landscape painting in the 20th century than Max Rupert Angus. Born in Hobart in 1914 and trained at Hobart Technical College, Angus spent decades painting the state’s coastlines, highlands, and forests with a clarity and intimacy that owed little to European models. He worked primarily in watercolour—a medium associated with delicacy and control—but applied it with a boldness that captured not just the shapes of the land, but its weather and mood.

Angus’s palette was reserved but never dull. He favoured cool greys, olive greens, deep blues, and stony browns—colours pulled directly from Tasmania’s environment. In his views of places like Mount Wellington, Lake Pedder, and Marion Bay, clouds hang low and rock faces hold their weight. There is no theatrical light, no romantic haze. These are not landscapes reimagined as symbols. They are real places, seen by someone who knew them intimately.

In the mid-century years, Angus helped organise painting trips with a loose group of artists and enthusiasts sometimes referred to as the “Sunday painters.” These excursions took him across the state—from coastal inlets to mountain plateaus—and were as much about presence as production. The act of being in the landscape, of watching it change over hours or days, informed his work. His paintings are quiet, steady, and unsentimental, and yet they are suffused with feeling. They belong to the land as much as they depict it.

Angus remained a central figure in Tasmanian art for over six decades. He exhibited regularly from the 1940s onward, won the Hobart City Art Prize, and was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia in recognition of his contribution to Australian art. Yet he stayed in Hobart, working from his studio and continuing to paint into his nineties. His long life allowed him to see the Tasmanian wilderness change—environmentally, politically, and visually—and his work stands as a record of both its continuity and its fragility.

Scale, Gesture, and the Tasmanian Sublime

Where Angus offered steadiness, Geoff Dyer brought force. Born in Hobart in 1947, Dyer was a different kind of landscape painter—less interested in fidelity, more concerned with energy. Trained at the Tasmanian School of Art, he rose to prominence in the 1970s and 80s with paintings that combined thick gesture, broken light, and emotional charge. His landscapes are not vistas; they are experiences. The viewer does not look into them—they are already inside.

Dyer often worked in oils, and his brushwork is vigorous, even aggressive. Rocks fracture across the canvas; sky is laid on in turbulent sweeps. In his later work, the imagery became increasingly abstract, though never fully divorced from place. You can still feel the ridgelines, the river bends, the storm forming over the Southern Ocean. His palette—smoky whites, ochres, flashes of orange or blood red—evokes a Tasmania that is more elemental than picturesque.

If Angus painted what he saw, Dyer painted what he felt. His landscapes are less about depiction than encounter. There is a sense of physical struggle in them—the artist grappling with space, matter, and light as though they might resist being pinned down. And indeed, that resistance is the point. Dyer did not try to explain Tasmania’s wilderness. He allowed it to remain difficult.

His expressive mode extended beyond landscape. Dyer was a successful portraitist, winning the Archibald Prize in 2003 for his portrait of writer Richard Flanagan. But his deepest engagement remained with place. Even his most abstract compositions carry the gravitational pull of Tasmanian earth and sky.

Wilderness as Modern Subject

By the late 20th century, the wilderness had become central not only to Tasmania’s visual culture, but to its identity. The environmental battles of the 1970s and 80s—the flooding of Lake Pedder, the Franklin River protests—infused the landscape with political resonance. Painters responded not with slogans but with attention. They looked harder, stayed longer, painted with a sense of urgency not because they were activists, but because they understood what might be lost.

In this context, the landscape became more than a subject. It was a ground of memory, conflict, and meaning. Artists like Angus and Dyer did not need to make that message explicit. Their work already contained it—in the choice of location, in the persistence of return, in the act of painting itself. The land was not inert. It was something lived in, walked through, and fought over.

- A watercolour of Lake Pedder, painted before its submergence, becomes a record of the vanished.

- A storm-lashed canvas, abstract but recognisable, suggests not place but pressure.

- A sketch from a high ridge, done in half an hour before the weather turned, holds more truth than any grand narrative.

These are not romantic images of escape. They are hard-won views.

Landscape Without Sentiment

The power of Tasmanian landscape painting in the late 20th century lies in its refusal of cliché. There are no shepherds, no sun-drenched hills, no compositional tricks borrowed from European masters. There is solitude, but not loneliness. There is wildness, but not wild fantasy. What artists like Angus and Dyer understood—each in their own way—was that the Tasmanian landscape did not need to be dramatised. It was already dramatic.

They brought to it different tools: one with watercolour’s transparency and patience, the other with oil’s force and density. But both sought to express something more than surface. Their works ask the viewer not simply to look, but to enter—to stand in the wind, to feel the cloud pass, to witness light as it flickers and fades across stone.

This is not a landscape that explains itself. It remains, even now, elusive. Which is why it continues to be painted.

Chapter 9: Printmakers, Potters, Builders – Mid-century to Late-century Craftspeople

From the 1950s to the late 20th century, Hobart’s art world expanded its boundaries—not just stylistically, but materially. This was a period when serious creative practice began to extend beyond oil painting and drawing into forms often marginalised by traditional art hierarchies: printmaking, ceramics, woodcraft, metalwork, and textile design. What set Hobart apart during this shift was not only its commitment to these practices as art forms, but the way in which the city’s institutions and artists sustained a close, collaborative culture of making.

The Studio as Workshop, Not Shrine

While painters continued to anchor much of Hobart’s visual output, the mid-century period saw a growing number of artists working in workshops, print rooms, kilns, and foundries. These were spaces of shared tools and shared knowledge. They were often modest—repurposed garages, school rooms, or co-op studios—but they became sites of experimentation and professional focus.

Many of these makers had trained at Hobart Technical College or the Tasmanian School of Art. Their grounding in drawing and design was traditional, but the materials they turned to were tactile and unforgiving. These artists printed by hand, turned timber on lathes, fired glazes in kilns built from scratch, and hammered metal until it revealed form. There was no romanticism in the work—just skill, repetition, and a deep engagement with process.

Printmaking in Hobart: Violet Vimpany and Bea Maddock

Printmaking had a long presence in Hobart, but it was Violet Vimpany who helped sustain it as a serious practice through the middle decades of the 20th century. A graduate of Hobart Technical College, Vimpany worked in both etching and painting, exhibiting regularly with the Art Society of Tasmania from the 1920s through the 1960s. Her prints, often of buildings, landscapes, and portraits, revealed a crisp line and strong structural sensibility. Working from a studio in the city, she printed small editions by hand, teaching privately and encouraging younger artists to take the medium seriously.

The arrival of Bea Maddock marked a new phase. Born in Hobart in 1934 and educated at the University of Tasmania, Maddock became one of Australia’s most significant printmakers. Though she would go on to study and work in Melbourne and abroad, her foundational training and early exhibitions were tied to Hobart. Maddock’s later work—particularly her large-scale intaglio and mixed-media pieces—revealed a conceptual ambition that elevated printmaking from the realm of craft into high art. Yet her methods remained rigorous: hand-inked plates, burnished lines, careful registration.

What Vimpany and Maddock shared—beyond geography—was a respect for process and an ability to use traditional methods to convey personal vision. In Hobart, their legacy helped establish printmaking as not merely a reproducible form, but as a vehicle for intimate and serious work.

The Cut Block and the Press: Kit Hiller and the Tasmanian Linocut

Kit Hiller, born in Hobart in 1948, trained at the Tasmanian School of Art during a time when modernist painting dominated. Yet her strongest contributions came in linocut printmaking, where she developed a highly personal, technically demanding approach. Working with reduction blocks—where each colour is carved from the same plate in successive layers—Hiller built vivid, stylised compositions that often featured native flora and fauna, interiors, and self-portraits.

Hiller’s prints, though widely exhibited throughout Tasmania and beyond, retained a homegrown quality. They were printed in modest studios, sold through regional galleries, and collected by both institutions and ordinary Tasmanians. Her Hobart training, and her participation in city-based exhibitions and artist networks, kept her practice rooted in the city even as her subject matter ranged more broadly.

What’s striking in Hiller’s work is its self-containment. These are not preparatory studies or secondary media—they are primary works. Her technique—demanding in precision and unforgiving in error—reflects the disciplined ethos that defined much of Hobart’s printmaking scene. Linocut, once considered a student’s tool, was transformed into a medium of refinement and control.

Clay, Timber, and Metal: Craft as Discipline

As printmaking flourished, other disciplines—ceramics, furniture making, and metalwork—found parallel growth in Hobart’s creative circles. The Art Society of Tasmania, along with smaller cooperative studios, hosted exhibitions that gave equal space to hand-thrown bowls and hand-tinted prints. For many artists, the separation between “fine” and “applied” arts had ceased to matter. The studio potter and the painter shared exhibition space, professional goals, and critical esteem.

The craft ethos in Hobart drew on the old Arts and Crafts foundations laid by Lucien Dechaineux and carried through the technical college system. It demanded honesty in materials, clarity in form, and fluency in technique.

In the late 20th century, Pete Mattila, an American-born blacksmith who settled in Hobart, carried this ethos forward in a new direction. Though working in steel and forging contemporary sculptural forms, Mattila continued the city’s tradition of material-centred practice. His forge, located in Hobart, became a locus for experimentation in metal as both utility and art. Working alone or collaboratively, he helped reassert the idea that objects—tables, knives, structural forms—could be artworks without ceasing to be functional.

In a city like Hobart, where industrial fabrication was limited and commercial demand for bespoke work was small, this kind of craftsmanship required not only skill, but resilience. Makers had to create their own audiences, their own sales networks, and often their own tools. But they also had freedom.

- A potter firing a kiln in a backyard studio near South Hobart.

- A printmaker hand-carving a lino block for an edition of 10.

- A blacksmith forging hinges for a commissioned sculpture, sparks lighting the walls.

These were not side projects or hobbies. They were central to Hobart’s visual culture.

An Architecture of Patience

What united Hobart’s craft traditions in this period—printmaking, pottery, metalwork, woodcraft—was a shared architecture of patience. These artists did not seek rapid innovation. They made their work in sequence, with hands and tools, in rooms where silence often prevailed. Their disciplines required time, repetition, and a tolerance for imperfection. In this way, they mirrored the rhythm of the city itself.

Hobart in the mid-to-late 20th century was not chasing trends. Its artists were not flooding biennales or joining conceptual movements abroad. But they were building something slower and, in many ways, more lasting: a community of makers who treated form with seriousness, and whose studios became the backbone of the city’s cultural infrastructure.

They didn’t need permission. They needed only space, tools, and time. And Hobart, for a long while, gave them all three.

Chapter 10: Art School Gravity – The University of Tasmania and its Centripetal Pull

Every city that becomes a centre for art must eventually become a centre for art education. In Hobart, this did not happen all at once, or under one name, or in one building. But over the course of the twentieth century, the city developed a gravitational core—a school that trained artists not just in how to draw or paint, but in how to see, how to think, and how to build a life in art. That core was the Tasmanian School of Art, and later, the University of Tasmania’s School of Creative Arts and Media. Its influence on Hobart’s cultural development was not peripheral. It was magnetic.

From Technical College to University

The roots of formal art education in Hobart began in the nineteenth century, but it was in the early twentieth that the structure began to harden into something lasting. Hobart Technical College offered drawing and design courses from the late 1800s, initially for tradesmen and applied artists. Over time, its art department grew more ambitious, adding painting, printmaking, and art history to its offerings.

By the mid-20th century, the College’s art school—under the leadership of figures like Lucien Dechaineux, and later Jack Carington Smith—had become Hobart’s de facto academy. It trained painters, printmakers, and sculptors, but also equipped them to teach, to exhibit, and to remain in Tasmania rather than leaving for the mainland. It gave Hobart a future in art, not just a past.

In 1962, this foundation deepened when the School of Art was formally incorporated into the University of Tasmania. What had once been a vocational training ground now had academic standing. It could offer degrees, attract research funding, and recruit staff from across Australia and beyond. It also began to develop a critical culture around art—connecting practice with theory, and making Hobart not just a place where artists were trained, but a place where they could contribute to national conversations.

The Studio as Compass

The shift from technical to university status changed how art was taught in Hobart, but it did not sever the link to studio practice. Unlike some universities, which treated fine art as an abstracted academic pursuit, the University of Tasmania retained a strong focus on making. The School of Art remained grounded in drawing studios, print workshops, and sculpture bays. Students were expected to work hard, to build technical skills, and to develop a language of form.

That focus on making had consequences. It attracted a certain kind of student—serious, materially engaged, unpretentious. And it produced a certain kind of graduate: one who could hold their own in a gallery, in a classroom, or in a solo studio.

Many of Hobart’s most significant artists from the postwar decades onward—figures such as George Davis, Kit Hiller, Geoff Dyer, and others—emerged from this environment. They were shaped not just by the teaching but by the ethos: the belief that good work comes from repetition, rigour, and long looking.

- A student spending six hours on a single still life.

- A drawing class dissecting anatomy before touching charcoal.

- A printmaker wiping down a copper plate for the seventh time, chasing a cleaner line.

These were not distractions from creativity. They were its precondition.

A Critical Mass

By the 1970s, the School had become the anchor of Hobart’s artistic scene. It employed practising artists as lecturers, hosted exhibitions of student and staff work, and cultivated a local audience interested in what was being made behind its doors. The energy around the school created a kind of feedback loop: artists stayed in Hobart to teach, students stayed to exhibit, and galleries emerged to show the work.

Art societies, which had once dominated Hobart’s exhibition calendar, now shared the stage with independent galleries and artist-run spaces formed by graduates. New print studios, photography labs, and interdisciplinary workshops formed in the shadow of the university, fed by its graduates and staff. Hobart’s small size, once considered a disadvantage, became a strength: everyone crossed paths, saw each other’s work, argued, collaborated.

It was around this time that the university began to draw interstate attention—not as a provincial school, but as a serious player in Australian art education. Visiting lecturers from the mainland were surprised by the depth of work coming out of Hobart’s studios. Critics noticed that some of the most grounded, technically proficient, and self-contained painters in the country were emerging from Tasmania. And many of them stayed.

Carington Smith’s Legacy and the Shape of the Curriculum

Jack Carington Smith, who led the art school for over two decades, was central to its ethos. Though trained in classical methods, he encouraged experimentation. He demanded rigour from his students but respected personal vision. His own painting—a blend of precise observation and modernist composition—set the tone for a school that embraced neither academic conservatism nor stylistic fashion.

Under his leadership, and that of his successors, the curriculum expanded to include not only painting and sculpture, but also design, photography, installation, and later digital media. Yet the foundation remained rooted in drawing, colour, and form. Even into the 1990s, students emerging from Hobart’s art school could often be identified by their technical clarity and their preference for understatement over spectacle.

This balance—between freedom and discipline, between innovation and control—became the hallmark of Hobart’s school. It shaped a city where artists talked more about light than ideology, where material knowledge mattered more than cleverness, and where serious work was expected to be slow.

The University as Cultural Anchor

The School of Art’s presence in Hobart had consequences beyond its walls. It trained not just artists, but teachers, curators, conservators, and critics who went on to populate every part of Tasmania’s cultural infrastructure. Its graduates led galleries, taught in schools, curated at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, and launched festivals. Even those who left the island often retained the habits formed in Hobart: clarity of form, distrust of trend, and respect for quiet craftsmanship.

The university also anchored the city in wider networks. Through exchanges, exhibitions, and research, it connected Hobart to Melbourne, Sydney, and London—not by chasing fashion, but by showing the quality of its work. It demonstrated that a city of modest size could support an art school of serious ambition.

And crucially, it made art a normal part of Hobart’s life. Exhibitions weren’t rare events—they were rhythms. Studios weren’t tucked away—they were downtown. The presence of the university meant that art was not imported. It was made, discussed, taught, and remembered—locally.

Education as Ecosystem

Today, Hobart’s creative life still draws strength from the university. The renamed School of Creative Arts and Media continues to train new artists, who in turn shape the city’s exhibitions, festivals, and visual language. The gravitational pull established decades ago remains in place.

The university doesn’t dominate Hobart’s art scene. But it holds it together. Like a workshop at the centre of town, its doors are always opening—sending artists out, bringing them back, building a place where art is not an ornament but a structure.

Chapter 11: Shock, Scale, and Spectacle – The MONA Effect

Few cultural institutions have reshaped a city with the force and finality of the Museum of Old and New Art. When MONA opened in Hobart in 2011, it did more than add a new gallery to the city’s art scene—it rewired how Hobart imagined itself. Funded by Hobart-born collector and professional gambler David Walsh, MONA did not build on the city’s existing traditions. It detonated them. The result was not a break with the past, but a provocation to see what might survive, evolve, or collapse under pressure.

MONA’s Arrival and Unorthodox Intentions

Built into the sandstone cliffs at Berriedale, a northern suburb of Hobart, MONA was a private museum disguised as a cultural earthquake. Visitors descend underground into vast galleries carved out beneath the ground, where ancient artefacts sit beside contemporary video art, and provocative installations crowd the senses. From the beginning, MONA’s curatorial stance was clear: discomfort, confrontation, and scale would replace didacticism, reverence, and polite engagement.

David Walsh’s stated aim was to create a museum of sex and death. He succeeded in creating something even more destabilising—a museum of uncertainty. Nothing was arranged chronologically or thematically in a conventional way. There were no wall labels. Instead, visitors received a device called “the O,” which provided audio commentary and alternative interpretations. This was not designed to educate but to provoke choice, friction, and doubt.

The architectural experience reinforced this ethos. MONA was not a building that welcomed you; it swallowed you. Concrete corridors, low light, and moments of visual overwhelm turned the act of seeing art into a kind of sensory trial. It was both spectacle and ordeal.

A Museum That Redefined the City

MONA was not created in isolation. It was built in Hobart, and that decision mattered. Walsh could have placed his collection in Melbourne or Sydney, where media reach and foot traffic would be guaranteed. Instead, he rooted it in his hometown, on the site of his own winery, and in doing so made Hobart the axis of a new kind of cultural narrative.

Hobart, once seen as remote or conservative, became a destination for international art tourism. Visitors began to arrive not to pass through, but to stay—flying in for the express purpose of encountering MONA. The ferry ride from Brooke Street Pier became part of the ritual, setting the tone for a city in which water, art, and anticipation intertwined.

But MONA’s influence did not stop at its gates. It radiated outward. Local galleries adjusted their programming. Restaurants, design studios, hotels, and music venues began to position themselves within the same orbit. The language of scale and spectacle became familiar. And critically, the city’s own artists began to think differently—not by copying MONA’s style, but by recognising the altered context in which their work would now be seen.

Festivals and the Expansion of Cultural Space

MONA’s institutional footprint extended with the creation of two major festivals: MONA FOMA (summer) and Dark Mofo (winter). Both were headquartered in Hobart and quickly took over not just venues, but the atmosphere of the city itself.

Dark Mofo, in particular, became a defining feature of Hobart’s cultural calendar. Each June, the city surrendered itself to a mixture of light installations, sound art, performance, and ritualistic celebration. The winter solstice—once an ordinary marker of seasonal decline—became a moment of collective spectacle. The waterfront, Salamanca, the industrial north—each played host to installations that ranged from ambitious to disorienting.

What was most striking about these festivals was not simply their scale, but the way they repurposed the city. Warehouses became performance halls. Docks became stages. Streets became processional routes. Hobart itself became the medium.

Local Artists and MONA’s Long Shadow

For Hobart-based artists, MONA was both gift and challenge. On one hand, it expanded the audience for contemporary art dramatically. It brought critics, curators, collectors, and curious travellers into a city previously peripheral to Australia’s art world. It demonstrated that serious, difficult, and ambitious work could be made and seen in Hobart.

On the other hand, MONA set a new benchmark for attention. Its exhibitions were loud, unpredictable, and well-funded. For smaller galleries and individual artists, this posed a dilemma: how to remain visible without competing in terms set by an institution that specialised in provocation?

Some artists leaned into this tension, exploring darker or more immersive work. Others went in the opposite direction—doubling down on intimacy, local materials, or subtle forms. In either case, the city’s artistic rhythm changed. No longer was Hobart simply a place of quiet realism or craft discipline. It had become a place of contradiction, energy, and creative recalibration.

MONA’s Place in Hobart’s Continuum

Despite its dramatic entrance, MONA did not erase Hobart’s artistic past. Rather, it brought that history into sharper relief. Against MONA’s scale and spectacle, the traditions of printmaking, realist painting, and studio craftsmanship appeared even more grounded. The enduring role of the University of Tasmania’s School of Creative Arts and Media, the continuing operation of the Art Society of Tasmania, and the persistence of long-established studios all suggested that MONA was not a replacement but an accelerant.

If anything, MONA has helped make Hobart’s full cultural ecology more legible. It brought international attention to a city that had long supported serious work in quiet ways. And it showed that new institutions could coexist with older rhythms—if the city had the confidence to let them.

A City Transformed, Not Rewritten

Today, Hobart carries both the excitement and the burden of the MONA effect. It is a city known for art in a way it never was before. But it is also a city negotiating what that means, and for whom. MONA does not define Hobart. It sits within it—strange, subterranean, luminous—and reflects back a version of the city that is neither false nor complete.

The true transformation may not be in the museum itself, but in the way Hobart now moves around it. The galleries, the festivals, the waterfront spaces, the university studios—all continue, altered not by imitation, but by relation. MONA changed Hobart not by making it something else, but by making its contradictions visible.

Chapter 12: Hobart Now – Painters, Installers, Builders, and Scene-Makers

The present moment in Hobart’s art history is not defined by any single movement, genre, or institution. It is defined by multiplicity. What makes Hobart’s current visual culture distinct is not merely its variety of styles, but the sheer density of creative lives concentrated within a small, navigable city. Walk from the waterfront to North Hobart and you will pass dozens of working studios, independent galleries, and performance venues. A linocut printer might be installing a show in a café; a sculptor might be preparing a commission for an underground bar; a video artist might be reconfiguring a space for a three-day intervention. The city breathes art not in spectacle alone, but in proximity.

After the Earthquake

The shock of MONA’s arrival in 2011 reshaped how Hobart was seen—but it did not erase or diminish the work of the artists already there. In the years since, Hobart has supported not just large institutions and festivals, but a wide base of independent practitioners. Some exhibit in national museums; others work quietly in sheds, repurposed shopfronts, or shared studios, rarely leaving the city. This is not an art scene driven by ideology or trend. It is marked instead by durability, friction, and the slow accumulation of mastery.

One such presence is Heather B. Swann, born in Hobart in 1961. Though she now works between Tasmania and the mainland, Swann’s practice remains connected to the visual intelligence that marked Hobart’s earlier modernists: sculptural form drawn through shadow, distortion, and tactile surfaces. Her objects—often anthropomorphic, ambiguous, and finely made—speak to a surrealism grounded not in theory, but in sensation. She belongs to no movement, yet her work exemplifies the seriousness of Hobart’s contemporary sculpture.

A very different kind of energy pulses through the work of Jamin, a painter and muralist who lives and works in Hobart. His practice includes public installations, design commissions, and gallery exhibitions. Jamin’s visual language is bold, graphic, and often chaotic—filled with overlapping figures, glyph-like symbols, and saturated colour fields. Yet it is always crafted with a sense of place. His murals, many painted on buildings across Hobart, turn the city itself into a visual text. They are loud, but not empty. They look outward, but are built from within.

The Studio City

What binds these artists—and many others working now in Hobart—is a shared relation to the studio. This is not a city where art is outsourced. It is made in situ: conceived, built, and finished within walking distance of where it is shown.