Georgia, a country nestled at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, boasts a rich and multifaceted artistic heritage shaped by its unique geographic position and millennia of cultural interactions. For centuries, it has served as a bridge between civilizations, absorbing influences from Byzantium, Persia, the Islamic world, and later Russia, while maintaining an unmistakably distinct identity. Georgian art reflects this dynamic interplay, blending external inspirations with local traditions to create a legacy that is both diverse and deeply rooted in its national character.

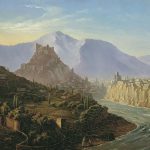

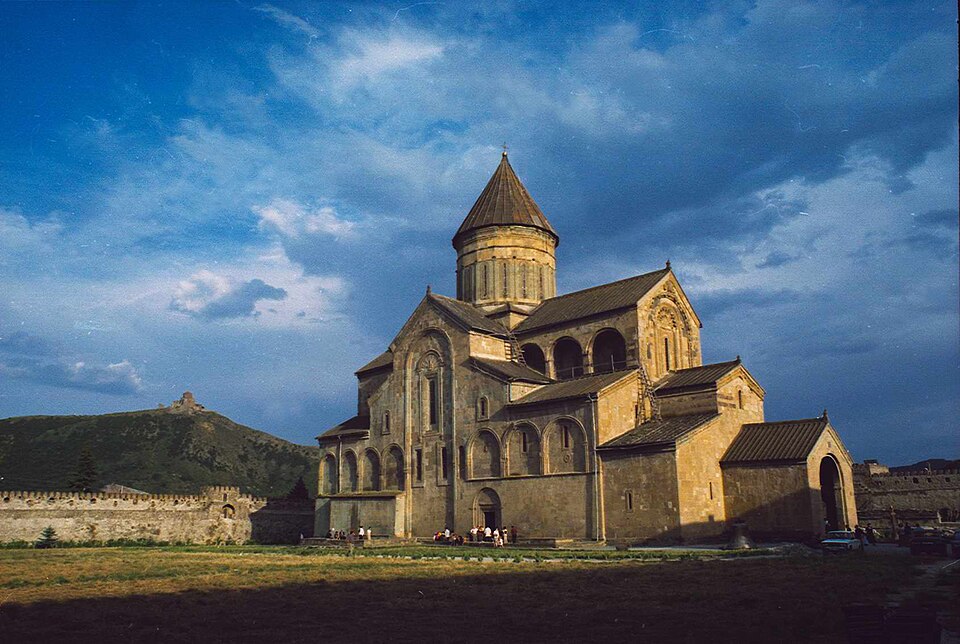

One of the most defining features of Georgian culture is its early adoption of Christianity in the 4th century, making it one of the first Christian nations in the world. This monumental shift profoundly influenced the development of Georgian art, particularly its architecture and religious iconography. Grand churches, adorned with vibrant frescoes and intricate stone carvings, became symbols of faith and resilience, embodying the spiritual and cultural heart of the nation. These sacred spaces, such as the iconic Svetitskhoveli Cathedral and Jvari Monastery, continue to stand as testaments to Georgia’s deep devotion and artistic ingenuity.

The Georgian Golden Age, spanning the 12th and 13th centuries, marked a high point in the nation’s artistic and cultural achievements. During this period, under the reign of King David IV and Queen Tamar, Georgia flourished as a hub of creativity, producing masterpieces in painting, architecture, and decorative arts. Monumental works like the Gelati Monastery and the frescoes of Vardzia exemplify the era’s fusion of Byzantine sophistication with uniquely Georgian elements, showcasing a refined aesthetic that resonates with spiritual and national pride.

Despite centuries of foreign domination—by the Mongols, Persians, Ottomans, and Russians—Georgian art has remained remarkably resilient. Artists and craftsmen found ways to incorporate outside influences while preserving their own traditions, resulting in an enduring legacy of adaptability and innovation. From medieval illuminated manuscripts to the vibrant canvases of modernists like Niko Pirosmani, Georgian art has always been a reflection of the nation’s history, struggles, and aspirations.

Today, Georgian art continues to thrive, with contemporary artists exploring themes of identity, heritage, and global connection. Institutions such as the Georgian National Museum and events like the Tbilisi Art Fair showcase the country’s vibrant creative scene, ensuring that Georgia’s rich artistic traditions remain relevant in the modern world.

Themes in Georgian Art

The recurring themes in Georgian art underscore its unique cultural identity and the resilience of its people:

- Faith and Spirituality: As one of the earliest Christian nations, Georgia has long used art to express its spiritual devotion. This is evident in its iconic Orthodox churches, adorned with frescoes and intricate carvings that combine theological depth with artistic beauty. Georgian iconography, influenced by Byzantium, often incorporates local elements, creating a distinct style that celebrates both faith and national identity.

- Cultural Resilience: Georgian art has often served as a tool for preserving identity in times of foreign domination. Despite invasions and political upheavals, Georgian artists maintained their unique traditions while adapting outside influences. This blend of persistence and innovation can be seen in the vibrant frescoes, intricate metalwork, and illuminated manuscripts that document the nation’s long history of endurance.

- Nature and Symbolism: Georgia’s dramatic landscapes have always been a source of inspiration for its artists. From the rolling vineyards of Kakheti to the soaring peaks of the Caucasus, nature features prominently in Georgian art. Symbols such as vines, animals, and celestial motifs appear in religious and decorative works, reflecting the spiritual and cultural significance of the natural world in Georgian life.

Chapter 1: Prehistoric and Ancient Georgian Art (4000 BCE–4th Century CE)

Georgia’s artistic heritage stretches back thousands of years, beginning with its prehistoric cultures and the ancient kingdoms of the region. As one of the oldest continuously inhabited areas in the world, Georgia boasts a rich archaeological record, offering glimpses into the artistic achievements of its earliest peoples. From intricately crafted metalwork to enigmatic rock carvings, the art of prehistoric and ancient Georgia reflects a society deeply connected to its environment and engaged in trade and cultural exchange.

Prehistoric Georgia: Petroglyphs and Early Craftsmanship

The earliest evidence of art in Georgia comes from petroglyphs and artifacts dating back to the Stone and Bronze Ages.

- Petroglyphs of Trialeti and Dzudzuana:

- Carved into stone surfaces, these ancient drawings depict human figures, animals, hunting scenes, and symbolic patterns. The Trialeti petroglyphs (dating to approximately 3000 BCE) are among the most significant examples, showcasing early attempts at narrative art.

- These carvings likely held ritual or spiritual significance, connecting early Georgians to their environment and the cycles of nature.

- Bronze Age Metallurgy (c. 3000–2000 BCE):

- Georgia became a center for metallurgy during the Bronze Age, with artisans producing sophisticated tools, weapons, and decorative objects. Items such as axes, daggers, and jewelry feature intricate designs that reflect both practical and ceremonial uses.

- The Trialeti culture, known for its distinctive burial mounds or kurgans, produced lavish artifacts, including gold and silver jewelry, richly adorned ceremonial vessels, and ornate weapons. These objects reveal the technical skill and artistic imagination of early Georgian metalworkers.

The Kingdom of Colchis: Myths and Golden Artifacts

The ancient kingdom of Colchis, located in western Georgia, is famously associated with the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts and their quest for the Golden Fleece. This myth highlights the region’s reputation for wealth and craftsmanship.

- Colchian Goldsmithing:

- Archaeological finds from Colchis include finely crafted gold ornaments, such as necklaces, earrings, and brooches, often adorned with intricate geometric patterns and naturalistic motifs like animals and plants.

- The use of gold in these artifacts suggests that Colchis was a center of wealth and a hub for trade, exporting metalwork to neighboring regions.

- The Golden Fleece and Metallurgy:

- Some historians believe the Golden Fleece myth may have originated from Colchis’s ancient practice of using sheepskins to sift gold from rivers. This unique method underscores the region’s advanced understanding of metallurgy.

Rock-Cut Monuments and Early Settlements

Early settlements in Georgia demonstrate a keen understanding of architectural and artistic principles.

- Uplistsikhe (c. 1000 BCE):

- This ancient rock-cut city in eastern Georgia, carved directly into cliffs, features an array of dwellings, temples, and storage facilities. While primarily functional, Uplistsikhe includes decorative elements, such as carved columns and reliefs, that highlight the artistic sensibilities of its builders.

- Sioni Petroglyphs:

- These rock carvings, found near Kazbegi, depict scenes of daily life and mythological figures, offering insights into the beliefs and practices of early Georgians.

The Iberian Kingdom and Hellenistic Influence

By the 4th century BCE, Georgia was home to two major kingdoms: Colchis in the west and Iberia (Kartli) in the east. The Kingdom of Iberia played a significant role in fostering cultural exchange with the Hellenistic world.

- Hellenistic Artifacts:

- Items such as pottery, sculptures, and coins from the Iberian Kingdom reveal a blend of Greek styles with local traditions. Vessels often feature classical shapes adorned with distinctly Georgian patterns.

- Architectural Innovations:

- Early fortifications and temples from the Iberian period showcase advanced construction techniques, incorporating elements of Greek and Persian design.

Themes of Prehistoric and Ancient Georgian Art

Art from this period reflects the ingenuity, spirituality, and cultural exchange that defined early Georgian society:

- Connection to Nature: From petroglyphs to metalwork, early Georgian art often drew inspiration from the surrounding landscape, with motifs featuring animals, plants, and celestial patterns.

- Trade and Influence: The wealth of Colchis and the strategic position of Iberia fostered interactions with Greek, Persian, and Mesopotamian cultures, enriching Georgian art with diverse influences.

- Spiritual Expression: Many artifacts and monuments suggest a focus on ritual and belief, from burial mounds to rock carvings depicting mythological themes.

The Transition to Christianity

The adoption of Christianity in the 4th century would mark a transformative shift in Georgian art, as spiritual expression took center stage. Early churches and Christian iconography would come to define Georgia’s visual culture, building on the artistic foundations of its prehistoric and ancient past.

Chapter 2: The Christianization of Georgia and Early Medieval Art (4th–9th Century)

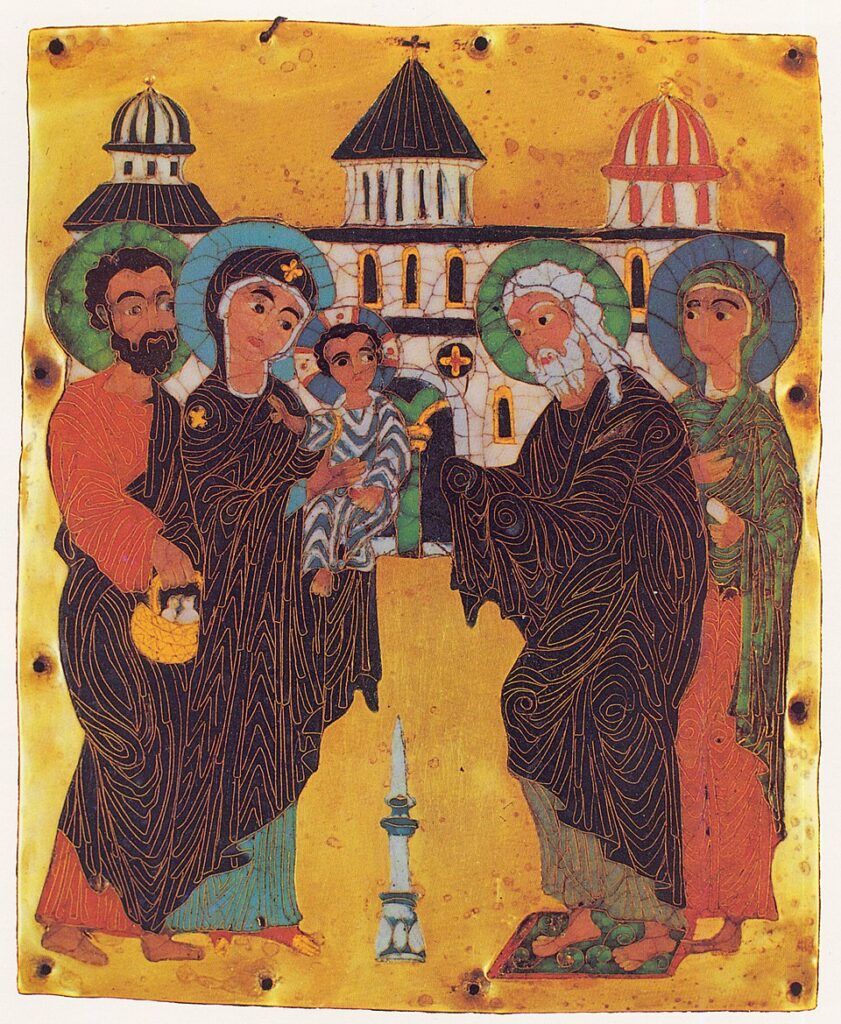

The Christianization of Georgia in the 4th century was a pivotal moment in the nation’s history, shaping its cultural and artistic identity for centuries to come. As one of the earliest Christian nations, Georgia quickly developed a rich tradition of religious art and architecture that blended local craftsmanship with influences from Byzantium and the Eastern Orthodox Church. During this period, monumental churches, illuminated manuscripts, and sacred icons became central to Georgian art, serving as expressions of faith and markers of a flourishing spiritual culture.

The Introduction of Christianity and its Impact

Georgia’s conversion to Christianity is traditionally attributed to Saint Nino, a Cappadocian woman who introduced the faith to the Kingdom of Iberia in the early 4th century. This shift brought profound changes to Georgian society and its artistic traditions.

- Adoption of the Cross Symbol:

- The cross became a defining motif in Georgian art, appearing in stone carvings, frescoes, and jewelry. The Grapevine Cross, associated with Saint Nino, symbolizes the fusion of Christian theology with Georgia’s agrarian culture.

- Byzantine Influence:

- As an ally of the Byzantine Empire, Georgia adopted many elements of Byzantine religious art, including iconography, architectural forms, and mosaic techniques, while infusing them with local character.

Early Christian Architecture

The introduction of Christianity led to a surge in church construction, establishing architectural forms that would define Georgian sacred spaces for centuries.

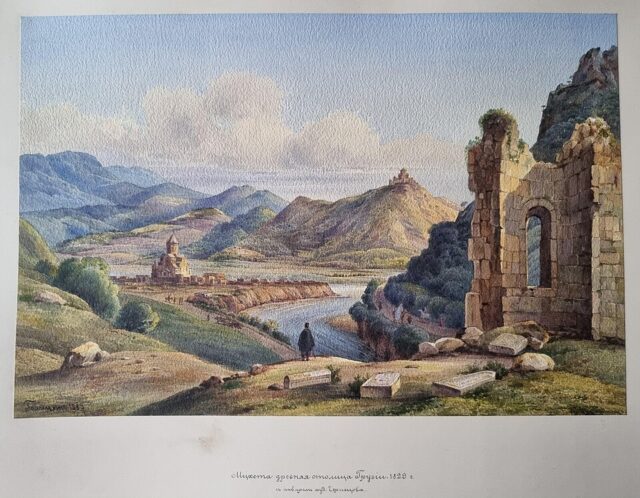

- Jvari Monastery (6th Century):

- Located near Mtskheta, this UNESCO World Heritage Site is one of the earliest and most iconic examples of Georgian Christian architecture. Its tetra-conch design (a cross-shaped layout with apses) influenced countless subsequent churches in Georgia.

- The simplicity and harmony of Jvari’s structure reflect the merging of local architectural traditions with Byzantine styles.

- Svetitskhoveli Cathedral (4th–5th Century):

- Built in Mtskheta, Georgia’s spiritual heart, this cathedral is said to enshrine the burial site of Christ’s robe. Its early basilica form was later transformed into a grander architectural masterpiece during the 11th century.

- Rock-Cut Monasteries:

- Early monastic complexes like those in David Gareja showcase the ingenuity of Georgian builders, who carved chapels and cells into rocky cliffs, blending art with the natural environment.

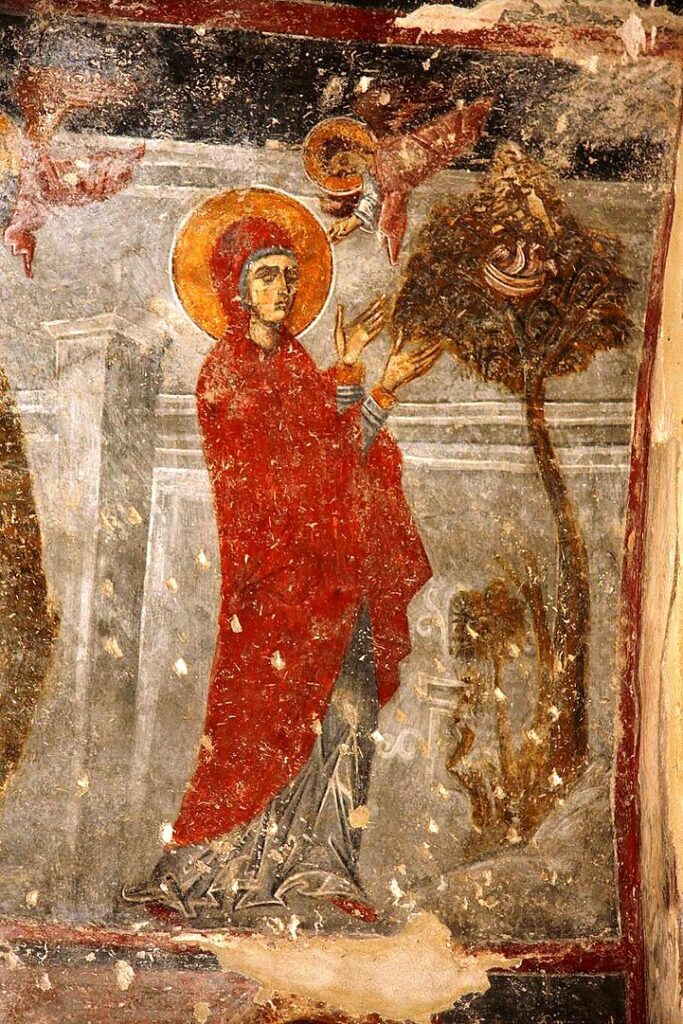

Frescoes and Iconography

The interior decoration of churches became a primary medium for Georgian artists to convey Christian narratives and theological concepts.

- Early Frescoes:

- Churches like those in Martvili and Bolnisi feature frescoes depicting biblical scenes, saints, and symbolic imagery. These paintings often incorporate vivid colors and expressive figures, emphasizing spiritual themes over naturalistic representation.

- Unique Georgian Iconography:

- Georgian icons, while influenced by Byzantine traditions, developed distinct characteristics. Local saints and cultural motifs, such as grapevines and mountain landscapes, were often integrated into religious imagery.

Stone Carvings and Reliefs

Stone carving emerged as a prominent art form during this period, with intricate reliefs adorning church facades, altars, and khachkars (cross-stones).

- Decorative Motifs:

- Georgian stone carvers combined Christian symbols like the cross with local patterns, including intertwining vines, animals, and celestial designs.

- Bolnisi Sioni Church (5th Century) is notable for its carved inscriptions and symbolic reliefs, considered among the oldest examples of Georgian Christian art.

Illuminated Manuscripts

The Christianization of Georgia also sparked a flourishing tradition of manuscript illumination, with monasteries becoming centers of artistic and scholarly activity.

- The Adysh Gospels (9th Century):

- One of the oldest surviving Georgian manuscripts, this text features intricately decorated pages with vibrant colors and geometric patterns, reflecting the synthesis of Byzantine and local styles.

- Monastic Scriptoria:

- Georgian monasteries, such as those at Gelati and Shio-Mgvime, played a crucial role in producing illuminated manuscripts, preserving both religious texts and artistic heritage.

Themes of Early Christian Georgian Art

This period of Georgian art is defined by its integration of spirituality, local tradition, and cross-cultural influence:

- Faith as Central: Art became a means of expressing and reinforcing Christian faith, evident in monumental churches, frescoes, and icons.

- Adaptation and Innovation: While heavily influenced by Byzantine traditions, Georgian artists developed unique styles that reflected their cultural identity.

- Connection to Nature: The blending of architecture with the natural landscape, as seen in rock-cut monasteries, highlights Georgia’s enduring relationship with its environment.

The Transition to the Golden Age

By the 9th century, Georgia’s political stability and growing cultural confidence set the stage for a flourishing of art and architecture during the Golden Age. The next chapter will explore how this period elevated Georgian creativity to new heights, producing some of the most iconic works in the nation’s history.

Chapter 3: The Golden Age of Georgian Art (9th–13th Century)

The Golden Age of Georgian art, spanning from the 9th to the 13th century, represents a period of unparalleled cultural and artistic achievement. This era coincided with Georgia’s political and economic ascent under the reigns of visionary leaders like King David IV (David the Builder) and Queen Tamar the Great. With newfound stability and prosperity, Georgian artists and architects created masterpieces in frescoes, manuscript illumination, metalwork, and monumental architecture that continue to define the nation’s cultural identity.

Architectural Marvels of the Golden Age

Architecture reached its zenith during the Golden Age, with the construction of grand monasteries, cathedrals, and fortified complexes that showcased a distinct Georgian style.

- Gelati Monastery (1106):

- Founded by King David IV, this UNESCO World Heritage Site is a masterpiece of medieval Georgian architecture. The monastery served as both a spiritual and educational center, featuring exquisite frescoes, mosaics, and relief carvings.

- The Church of the Virgin within Gelati is particularly notable for its vibrant frescoes depicting biblical narratives and saints, rendered in a style that blends Byzantine precision with Georgian creativity.

- Vardzia Cave Monastery (12th Century):

- Commissioned by Queen Tamar, this monumental rock-hewn monastery exemplifies Georgia’s ingenuity and devotion. Carved into a cliffside, Vardzia includes over 600 rooms, chapels, and storage spaces, all interconnected through tunnels.

- The Church of the Dormition, located within the complex, features frescoes of Queen Tamar and her father, King George III, marking it as a unique fusion of royal and religious art.

- Svetitskhoveli Cathedral (Rebuilt in the 11th Century):

- Located in Mtskheta, the spiritual heart of Georgia, this cathedral was reconstructed during the Golden Age to become a grand example of Georgian Orthodox architecture. Its soaring arches, decorative stone carvings, and symbolic imagery represent the culmination of centuries of architectural evolution.

Frescoes: A Visual Narrative of Faith

Fresco painting flourished during the Golden Age, adorning the interiors of churches and monasteries with vivid depictions of biblical stories and saints.

- Themes and Style:

- Frescoes often emphasized spiritual themes, using vibrant colors, dynamic compositions, and expressive figures to convey theological narratives.

- The frescoes at Gelati Monastery and Betania Monastery are notable for their emotional depth and sophisticated use of perspective.

- Royal Imagery in Frescoes:

- Kings and queens, such as Queen Tamar, were frequently depicted in church frescoes, symbolizing their divine right to rule and their role as protectors of the faith.

- The image of Queen Tamar at Vardzia Monastery remains one of the most iconic depictions of Georgia’s revered monarch.

Illuminated Manuscripts: A Fusion of Art and Scholarship

Golden Age monasteries became centers of learning and creativity, producing illuminated manuscripts that rank among Georgia’s greatest artistic achievements.

- The Four Gospels of Jruchi (10th–11th Century):

- These manuscripts feature ornate initials, intricate borders, and miniature illustrations that combine Byzantine influences with uniquely Georgian elements.

- The use of gold leaf and vibrant pigments reflects the high level of skill and resources devoted to manuscript production during this period.

- The Shatberdi Codex (9th Century):

- One of the oldest surviving Georgian manuscripts, this codex includes detailed illustrations of saints and theological symbols, showcasing the precision and creativity of Georgian scribes.

Metalwork and Decorative Arts

Georgian metalwork reached new heights during the Golden Age, with artisans creating intricately designed religious and ceremonial objects.

- Icons and Reliquaries:

- Precious metals such as gold and silver were used to craft icons and reliquaries, often encrusted with gems and adorned with intricate engravings.

- The Khakhuli Triptych, a gilded altar piece, is one of the most famous examples of Georgian metalwork, blending elements of Byzantine, Georgian, and regional styles.

- Crosses and Jewelry:

- Georgian crosses, including processional and altar crosses, featured elaborate carvings and symbolic motifs. Many incorporated local patterns, such as grapevines and floral designs, symbolizing life and faith.

Themes of the Golden Age

Art from this period reflects Georgia’s cultural confidence and spiritual devotion, characterized by:

- Harmony and Grandeur: Architecture and frescoes from the Golden Age emphasize symmetry, scale, and balance, reflecting the prosperity and stability of the era.

- Faith and Identity: Religious art and literature reinforced Georgia’s Orthodox Christian identity, with churches serving as both spiritual centers and symbols of national pride.

- Royal Patronage: The active involvement of rulers like King David IV and Queen Tamar in commissioning art ensured that this era’s works reflected both spiritual and political ideals.

The Decline of the Golden Age

The Mongol invasions of the 13th century marked the end of Georgia’s Golden Age, bringing political turmoil and economic hardship that disrupted its artistic flourishing. However, the works created during this period continue to inspire, standing as enduring symbols of Georgia’s creativity and resilience.

Chapter 4: Medieval Metalwork and Manuscripts (9th–15th Century)

From the 9th to the 15th century, Georgian art flourished in the realms of metalwork and manuscript illumination, two mediums that showcased the nation’s technical skill, aesthetic sensibilities, and deep spiritual devotion. During this period, Georgian artisans created intricate objects of religious and ceremonial significance, while scribes and illuminators produced manuscripts that remain cultural treasures. These works not only reflect Georgia’s Orthodox Christian identity but also demonstrate the blending of local traditions with Byzantine and regional influences.

Metalwork: Icons, Crosses, and Ceremonial Objects

Georgian metalwork during this period epitomized the union of faith and craftsmanship, with artisans producing exquisite works for the Orthodox Church and the royal courts.

- Icons and Enamel Art:

- Georgian artisans were renowned for their cloisonné enamel work, a technique used to create vibrantly colored designs on religious icons.

- The Khakhuli Triptych (12th Century) is one of the most famous examples, a gilded altar piece encrusted with gemstones and adorned with intricate enamel panels depicting saints and biblical scenes.

- Processional and Altar Crosses:

- Metal crosses were a central feature of Georgian Orthodox worship, often made of gold or silver and decorated with engravings, filigree, and jewels.

- The Anchiskhati Cross, crafted in the 6th or 7th century and preserved through the medieval era, features intricate geometric patterns and symbolic motifs, emphasizing the spiritual significance of the cross.

- Liturgical Vessels and Reliquaries:

- Chalices, censers, and reliquaries from this period were adorned with intricate patterns and Christian imagery.

- Reliquaries, such as the Martvili Reliquary, were crafted to house sacred relics and became focal points of devotion.

Manuscript Illumination: A Marriage of Art and Theology

The creation of illuminated manuscripts was a significant artistic achievement of medieval Georgia, combining theological scholarship with visual storytelling.

- Centers of Manuscript Production:

- Monasteries such as Gelati, Iqalto, and Shatberdi served as centers of manuscript creation, where scribes and illuminators worked meticulously to produce texts that were both sacred and visually stunning.

- Georgian monasteries abroad, such as those on Mount Athos in Greece and in Jerusalem, also contributed to the development of Georgian manuscript traditions.

- The Adysh Gospels (9th Century):

- Among the oldest surviving Georgian manuscripts, the Adysh Gospels are notable for their vibrant illuminations, including geometric borders and symbolic decorations.

- The manuscript exemplifies the synthesis of Byzantine stylistic elements with uniquely Georgian motifs, such as grapevines and local flora.

- The Jruchi Gospels (10th–11th Century):

- These manuscripts are celebrated for their ornate initials, miniature illustrations, and use of gold leaf. Their pages combine delicate line work with bold colors to highlight key biblical passages.

Decorative Techniques and Styles

The manuscripts and metalwork of medieval Georgia shared several stylistic and decorative elements, reflecting a unified artistic vision.

- Geometric and Floral Patterns:

- Both manuscripts and metalwork feature intricate patterns inspired by nature, including vines, flowers, and stars. These motifs symbolize growth, faith, and the divine order.

- Symbolism and Iconography:

- Artisans and illuminators incorporated Christian symbols such as crosses, halos, and celestial imagery, imbuing their works with layers of spiritual meaning.

- Color and Material:

- Vibrant pigments, gold leaf, and precious stones were used to create a sense of grandeur and sanctity, emphasizing the divine nature of these objects.

Themes of Medieval Metalwork and Manuscripts

The art of this period reflects Georgia’s devotion to its faith and its cultural connections to the broader Christian world:

- Faith and Worship: Metal objects and manuscripts were created to glorify God and serve as tools of worship, emphasizing the centrality of religion in Georgian life.

- Technical Mastery: The complexity of Georgian metalwork and the detailed precision of illuminated manuscripts demonstrate the high level of skill among artisans and scribes.

- Cultural Exchange: While grounded in Georgian traditions, these works show influences from Byzantium, the Islamic world, and neighboring regions, highlighting Georgia’s role as a crossroads of cultures.

The Transition to the Early Modern Period

The late medieval period saw Georgia face increased challenges, including invasions by the Mongols, Persians, and Ottomans. Despite these hardships, the nation’s artistic traditions endured, setting the stage for new forms of cultural expression during the early modern era.

Chapter 5: Persian and Ottoman Influences (15th–18th Century)

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, Georgia faced repeated invasions and periods of domination by powerful neighboring empires, particularly the Persian Safavids and the Ottoman Turks. These geopolitical shifts introduced new artistic influences into Georgian culture, resulting in a fusion of local traditions with Persian and Ottoman aesthetics. During this era, Georgian art evolved to reflect both the resilience of its people and the complex cultural exchanges that defined this tumultuous period.

Persian Influence on Georgian Art

Persian cultural dominance, particularly during the Safavid period, left a lasting impact on Georgian art and architecture.

- Miniature Painting:

- Persian miniature painting became a popular form of artistic expression in Georgian courts, blending Georgian themes with the intricate styles of Safavid Persia.

- Manuscripts from this era often depict courtly life, religious stories, and mythological themes in fine detail, using rich colors and delicate brushwork.

- The Rustaveli Manuscript Illustrations of The Knight in the Panther’s Skin reflect Persian artistic techniques while celebrating Georgia’s literary heritage.

- Metalwork and Decorative Arts:

- Georgian craftsmen adopted Persian techniques in metalworking, producing ornate daggers, swords, and jewelry adorned with floral motifs and calligraphy.

- The influence of Persian design is particularly evident in ceremonial objects, such as gilded sword hilts and enameled vessels.

- Carpets and Textiles:

- Persian carpet-making traditions influenced Georgian textiles, leading to the production of intricately woven rugs and wall hangings.

- Georgian carpets from this period often incorporated Persian-inspired geometric patterns, floral designs, and vibrant color palettes, while retaining elements unique to the region.

Ottoman Influence on Georgian Art

Ottoman domination, particularly in western Georgia, introduced Islamic artistic motifs and architectural styles into Georgian culture.

- Islamic Architecture:

- The construction of mosques in regions under Ottoman control, such as Adjara, introduced domes, minarets, and decorative tilework to Georgian architecture.

- While Christian churches remained dominant in much of Georgia, Ottoman architectural features were sometimes integrated into Georgian buildings, creating a hybrid style.

- Ceramics and Pottery:

- Ottoman techniques in ceramic glazing and decoration influenced Georgian pottery, leading to the creation of richly patterned plates, bowls, and tiles.

- Georgian potters blended traditional forms with Ottoman floral and geometric motifs, producing works that appealed to both local and foreign patrons.

- Weaponry and Armor:

- Georgian blacksmiths, influenced by Ottoman designs, produced finely crafted weapons and armor that were both functional and decorative. These items often featured Arabic inscriptions and Islamic patterns alongside Georgian motifs.

Fusion of Styles in Religious Art

Despite the dominance of Persian and Ottoman powers, Georgian religious art maintained its distinct identity while incorporating foreign influences.

- Church Architecture:

- In regions under Persian and Ottoman rule, Christian churches adapted their designs to reflect local constraints, often blending Islamic patterns and forms with traditional Georgian styles.

- Frescoes from this period, such as those in the Ikalto Monastery, show a mixture of Persian-influenced floral designs and traditional Christian iconography.

- Icons and Crosses:

- Christian icons and crosses continued to be produced, often using Persian techniques like cloisonné enamel and filigree work. These objects symbolized Georgia’s spiritual resistance to foreign domination.

Literature and Calligraphy

Literary and artistic traditions also flourished during this period, reflecting the blending of Persian and Georgian influences.

- Rustaveli’s Legacy:

- Illustrations of Shota Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther’s Skin during this era incorporated Persian miniature painting styles, enriching the visual interpretation of this iconic Georgian epic.

- Islamic Calligraphy:

- Persian and Ottoman styles of calligraphy influenced Georgian script, particularly in decorative manuscripts and inscriptions on metalwork and textiles.

Themes of Persian and Ottoman Influence

Art from this period reflects the resilience and adaptability of Georgian culture:

- Cultural Fusion: Georgian artists absorbed Persian and Ottoman influences, integrating them with local traditions to create unique works.

- Spiritual Resistance: Religious art and architecture remained central to Georgian identity, symbolizing the nation’s determination to preserve its Christian heritage.

- Artistic Innovation: Exposure to Persian and Ottoman techniques enriched Georgian craftsmanship, leading to new forms of expression in painting, metalwork, and textiles.

The Transition to Russian Influence

By the late 18th century, Georgia sought protection from the growing Russian Empire, leading to new political realities and artistic trends. The next chapter will explore how Georgian art evolved under Russian rule in the 19th century, incorporating European academic styles while maintaining its national character.

Chapter 6: Georgian Art in the Russian Empire (19th Century)

The annexation of Georgia by the Russian Empire in the early 19th century marked a significant turning point in Georgian art and culture. While Russian rule brought challenges to Georgia’s autonomy, it also introduced new artistic movements and styles, particularly those emerging from European academic traditions. Georgian artists began to navigate the dual influences of Russian imperial culture and their own national heritage, producing works that reflected both adaptation and resistance.

The Influence of European Academic Traditions

Russian control opened the doors for Georgian artists to study at prestigious institutions in St. Petersburg and Moscow, exposing them to European art movements such as Romanticism, Realism, and Impressionism.

- Romanticism and Georgian Nationalism:

- Inspired by the Romantic movement, Georgian artists often used their work to celebrate the nation’s landscapes, traditions, and people. This was both a reflection of pride in their heritage and a subtle form of cultural resistance against Russian domination.

- Grigol Maisuradze painted emotive scenes of Georgian landscapes, showcasing the dramatic mountains and valleys that symbolized the country’s resilience.

- Realism and Social Commentary:

- The rise of Realism in Russia influenced Georgian artists to depict the lives of ordinary people with honesty and empathy.

- Gigo Gabashvili (1862–1936) became one of Georgia’s most prominent painters during this period, capturing vivid scenes of rural life, Georgian festivals, and everyday moments.

Niko Pirosmani: A Folk Art Pioneer

One of the most iconic figures of 19th-century Georgian art is Niko Pirosmani (1862–1918), whose self-taught, naive style captured the essence of Georgian culture.

- Themes in Pirosmani’s Work:

- Pirosmani’s paintings often depicted Georgian folk traditions, including feasts, musicians, and rural life. His works, such as Feast of a Nobleman and Roe Deer Drinking from a Stream, celebrate the simplicity and vibrancy of Georgian life.

- He also painted animals and portraits, using bold, expressive lines and flat, vibrant colors.

- Legacy:

- Though unrecognized in his lifetime, Pirosmani’s work gained widespread appreciation in the 20th century, becoming a symbol of Georgian national identity.

Architecture: The Blend of Russian and Georgian Styles

The 19th century saw the construction of new public buildings and urban infrastructure influenced by Russian imperial styles, while traditional Georgian elements persisted.

- Tbilisi’s Urban Development:

- Under Russian rule, Tbilisi underwent significant modernization, with new boulevards, theaters, and public squares built in neoclassical and eclectic styles.

- The Rustaveli Theatre (1851) combines European architectural trends with subtle Georgian flourishes, reflecting the cultural synthesis of the time.

- Preservation of Religious Architecture:

- Despite the imposition of Russian imperial rule, Georgian Orthodox churches continued to be built and restored, preserving traditional designs and symbols.

Georgian Romanticism in Literature and Art

The Romantic spirit of the 19th century extended beyond visual art, influencing Georgian literature and its interplay with painting.

- Shota Rustaveli’s Legacy:

- Romantic illustrations of Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther’s Skin became popular, reflecting a renewed interest in Georgia’s medieval heritage.

- Alexander Orbeliani and the Literary Revival:

- The 19th century saw a surge in nationalistic literature, with writers like Alexander Orbeliani championing Georgian identity. This literary movement inspired visual artists to focus on Georgian themes in their work.

Thematic Exploration in Georgian Art under Russian Rule

Art from this period reflects the tension between Russian imperial influence and Georgian national identity:

- Cultural Pride and Resistance: Many works celebrated Georgian traditions, landscapes, and people, subtly asserting national identity in the face of foreign rule.

- Adaptation of European Styles: Exposure to European academic traditions enriched Georgian art, introducing techniques and styles that blended seamlessly with local aesthetics.

- Urban and Rural Duality: The contrast between urban modernization and rural traditions became a recurring theme, reflecting the social changes brought by Russian rule.

The Transition to Modernism

By the late 19th century, Georgian artists began to embrace modernist movements, experimenting with new forms and techniques. The next chapter will explore how Georgian art evolved in the early 20th century, navigating the challenges of Soviet influence and the rise of avant-garde movements.

Chapter 7: Modernism and Soviet Influence (1900–1991)

The 20th century marked a period of dramatic transformation for Georgian art. The collapse of the Russian Empire, the brief independence of the Georgian Democratic Republic (1918–1921), and the subsequent Soviet annexation (1921) profoundly impacted the cultural landscape. Georgian artists navigated the complexities of modernism and the ideological constraints of Socialist Realism, producing works that both adhered to and subtly subverted Soviet artistic policies. Despite these challenges, this period saw remarkable innovation, with Georgian modernist painters, filmmakers, and designers gaining recognition on the international stage.

The Early Modernist Movement (1900–1921)

The early 20th century witnessed the rise of Georgian modernism, as artists experimented with new styles and techniques influenced by European avant-garde movements.

- David Kakabadze (1889–1952):

- A pioneering modernist, Kakabadze blended elements of Cubism and Futurism with themes rooted in Georgian culture. His works, such as Imeretian Landscape (1918), juxtapose abstract forms with depictions of Georgia’s lush countryside.

- Kakabadze was also an innovator in multimedia art, experimenting with film, photography, and three-dimensional art.

- Lado Gudiashvili (1896–1980):

- Gudiashvili’s paintings from this era, such as Oriental Dancers and The Feast, reflect his fascination with Georgian folklore and Persian-influenced ornamentation. His style combined Symbolism and Expressionism, capturing the vibrancy of Georgian culture.

- Elene Akhvlediani (1898–1975):

- Akhvlediani is best known for her atmospheric cityscapes and depictions of Georgian architecture. Her works celebrate the unique character of Georgian urban life, blending modernist techniques with traditional themes.

The Soviet Era and Socialist Realism (1921–1950s)

Following Georgia’s annexation by the Soviet Union, the government imposed strict artistic guidelines under the doctrine of Socialist Realism, which emphasized depictions of workers, collective farms, and industrial progress.

- Soviet Restrictions:

- Georgian artists were required to produce works that glorified the Soviet state and avoided abstract or experimental styles. This led to a decline in overt modernist experimentation during the 1930s and 1940s.

- Themes of Socialist Realism:

- Paintings, sculptures, and murals often depicted scenes of collective labor, industrial progress, and idealized depictions of Soviet life. Works like Ucha Japaridze’s Building a Hydroelectric Plant (1934) exemplify this trend.

- Subtle Resistance:

- Despite restrictions, many Georgian artists embedded elements of national identity into their work. They used traditional motifs, local landscapes, and folklore to preserve Georgian culture within the framework of Soviet-approved art.

The Thaw and Artistic Freedom (1950s–1980s)

The death of Stalin in 1953 and the subsequent political “Thaw” under Khrushchev allowed for greater artistic experimentation and the revival of modernist trends.

- Abstract and Experimental Art:

- Artists like Zurab Tsereteli and Giorgi (Gia) Edzgveradze began to explore abstraction, conceptual art, and surrealism, breaking away from the constraints of Socialist Realism.

- Tsereteli’s monumental sculptures, such as The Friendship Monument in Gudauri (1983), blend Soviet monumentalism with distinctly Georgian motifs.

- The Revival of Traditional Motifs:

- Artists revisited themes from Georgian folklore, history, and religion, often as a subtle assertion of cultural identity. For instance, Lado Gudiashvili’s later works incorporated mythological themes that celebrated Georgia’s spiritual heritage.

Georgian Cinema and Avant-Garde Film

Georgian cinema flourished during the Soviet era, gaining international acclaim for its poetic storytelling and innovative visual style.

- Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990):

- A filmmaker of Armenian-Georgian descent, Parajanov’s masterpiece The Color of Pomegranates (1969) is a visually stunning work that draws on Georgian and Armenian cultural traditions. Though censored by Soviet authorities, his films became iconic for their avant-garde aesthetic.

- Tengiz Abuladze (1924–1994):

- Abuladze’s films, including Repentance (1984), critique totalitarianism and explore moral and philosophical themes, reflecting the tensions of Soviet life.

Themes of Modernism and Soviet Influence

Georgian art during this period reflects the complex interplay of innovation, oppression, and cultural resilience:

- Modernist Experimentation: Early 20th-century artists like Kakabadze and Gudiashvili pushed the boundaries of form and technique, incorporating European avant-garde influences into distinctly Georgian themes.

- Adaptation Under Soviet Rule: During the era of Socialist Realism, Georgian artists found ways to preserve their cultural identity through subtle references to local traditions and landscapes.

- Global Recognition: Despite ideological constraints, Georgian art and cinema gained international acclaim, demonstrating the creativity and resilience of its artists.

The Transition to Independence

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 ushered in a new era of Georgian art, marked by the rediscovery of creative freedom and a renewed engagement with themes of national identity. The next chapter will explore how Georgian artists navigated the post-Soviet landscape, embracing contemporary movements while drawing on their rich cultural heritage.

Chapter 8: Contemporary Georgian Art (1991–Present)

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the beginning of a new era for Georgian art. The country’s independence ushered in an age of creative freedom, allowing artists to explore themes of identity, history, and globalization. Contemporary Georgian art reflects a dynamic interplay of tradition and innovation, as artists engage with their cultural heritage while embracing global artistic trends. From painting and sculpture to multimedia and performance art, the Georgian art scene today is a vibrant and evolving expression of the nation’s identity.

Themes of Post-Soviet Georgian Art

Contemporary Georgian art explores a wide range of themes that reflect the nation’s past, present, and future.

- National Identity and Heritage:

- Many artists revisit Georgian history, folklore, and Orthodox Christian traditions in their work, using them as a lens to explore contemporary issues.

- This theme often manifests in reimagined icons, reinterpretations of folk motifs, and depictions of historic events.

- Social and Political Commentary:

- Georgian artists frequently address the challenges of post-Soviet life, including political instability, economic hardship, and the search for identity in a globalized world.

- Works often critique corruption, inequality, and the lingering effects of Soviet rule.

- Globalization and Cultural Exchange:

- While rooted in Georgian traditions, contemporary art often engages with global issues, such as climate change, migration, and technology.

- Artists incorporate diverse influences and media, reflecting Georgia’s integration into the global art community.

Key Figures in Contemporary Georgian Art

Several prominent Georgian artists have gained international recognition for their innovative and thought-provoking work.

- Zurab Tsereteli (b. 1934):

- Tsereteli continues to be a towering figure in Georgian art, known for his monumental sculptures. His works, such as The Friendship Monument in Gudauri, often blend traditional Georgian motifs with bold, modernist designs.

- Tamara Kvesitadze (b. 1968):

- A multidisciplinary artist, Kvesitadze is best known for her kinetic sculpture “Man and Woman” (2007) in Batumi, which symbolizes the meeting and separation of two lovers. Her work combines engineering precision with emotional depth.

- Giorgi (Gia) Edzgveradze (b. 1953):

- A conceptual artist, Edzgveradze uses painting, installation, and performance to explore themes of identity, freedom, and the human condition. His works often challenge social norms and provoke critical reflection.

- The Bouillon Group:

- This contemporary art collective creates multimedia works that address social and political issues in Georgia, blending performance, video, and installation art.

Georgian Cinema in the Contemporary Era

Georgia’s film industry continues to thrive, building on its Soviet-era legacy of poetic and avant-garde storytelling.

- Nana Ekvtimishvili and Simon Groß:

- This filmmaker duo gained international acclaim with films like In Bloom (2013) and My Happy Family (2017), which explore the complexities of Georgian society and family life.

- Dea Kulumbegashvili:

- Kulumbegashvili’s Beginning (2020) is a meditative and visually stunning exploration of faith, trauma, and societal power dynamics, earning accolades at major international film festivals.

Art Institutions and Biennials

The development of contemporary Georgian art has been supported by a growing network of institutions and events that promote local artists and connect them to the global art world.

- The Georgian National Museum:

- This institution oversees several key art museums and galleries, including the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, which showcases Georgian art from ancient to modern times.

- Tbilisi Art Fair:

- Established in 2018, this annual event brings together Georgian and international artists, galleries, and collectors, fostering cultural exchange and promoting Georgia’s contemporary art scene.

- Contemporary Art Spaces:

- Independent galleries and art spaces, such as Project ArtBeat and The Why Not Gallery, play a vital role in supporting emerging artists and experimental practices.

Multimedia and Experimental Art

Georgian artists have embraced a wide range of media and experimental approaches, reflecting the diversity of contemporary art.

- Photography and Video Art:

- Artists like Vato Tsereteli use photography and video to document and critique modern Georgian life, exploring themes of identity, memory, and social change.

- Performance and Installation:

- Performance art has become a prominent medium for addressing societal issues, often blending traditional Georgian elements with avant-garde techniques.

- Digital and Interactive Art:

- The rise of digital art has enabled Georgian artists to explore new forms of expression, engaging audiences in interactive and immersive experiences.

- Visual Arts, Music, and Digital Platforms:

- Trio Mandili (Tatuli Mgeladze, Mariam Kurasbediani and Tako Tsiklauri) blends traditional Georgian polyphonic singing with scenic visuals of Georgia’s landscapes, creating a unique harmony of music and art. Through YouTube, they bring Georgia’s cultural heritage to a global audience with innovative storytelling.

Themes of Contemporary Georgian Art

Contemporary Georgian art reflects the complexities of a nation navigating its post-Soviet identity while engaging with the global art scene:

- Tradition and Innovation: Artists balance respect for Georgian heritage with the desire to experiment and innovate.

- Social and Political Engagement: Many works address the realities of modern Georgian society, offering critical insights and fostering dialogue.

- Global Reach: Georgian artists are increasingly recognized on the international stage, contributing to global conversations on art and culture.

The Future of Georgian Art

As Georgia continues to evolve politically, socially, and culturally, its art remains a vital expression of the nation’s identity and aspirations. With a thriving community of artists, institutions, and events, Georgian art is poised to make an even greater impact on the global stage, ensuring that its rich cultural heritage is both preserved and reimagined for future generations.

Chapter 9: The Role of Folk Art and Craftsmanship Throughout Georgian History

Folk art and craftsmanship have been integral to Georgian culture for centuries, serving as a reflection of the nation’s traditions, values, and connection to its environment. From intricately woven textiles and hand-carved woodwork to stunning enamelwork and traditional jewelry, Georgian folk art is both functional and deeply expressive. Passed down through generations, these artisanal traditions have helped preserve Georgia’s unique cultural identity, even in the face of foreign invasions and political upheaval.

Textiles: A Legacy of Weaving and Embroidery

Georgian textile arts are among the oldest and most treasured forms of folk art, with techniques that date back to antiquity.

- Traditional Weaving:

- Georgian weavers have long been renowned for creating kilims (flat-woven rugs) and pile rugs, often featuring geometric patterns, floral motifs, and bold colors. These textiles were not only used for practical purposes, such as flooring and wall coverings, but also as symbols of status and tradition.

- The Tushetian rugs of eastern Georgia are particularly famous, known for their intricate designs and vibrant colors, often inspired by local flora and fauna.

- Embroidery:

- Georgian embroidery is characterized by its fine craftsmanship and symbolic designs, often used to adorn clothing, religious vestments, and household items. Common motifs include grapevines, animals, and crosses, symbolizing faith and fertility.

Woodworking and Architectural Ornamentation

Georgia’s abundant forests have made wood an essential material for both practical and decorative purposes.

- Wooden Furniture and Tools:

- Georgian artisans produced beautifully carved wooden furniture, such as chests, tables, and chairs, often featuring intricate geometric and floral patterns.

- Everyday items like spoons, bowls, and tools were also intricately carved, demonstrating the Georgian emphasis on blending functionality with artistry.

- Decorative Elements in Architecture:

- Wooden balconies, particularly in Old Tbilisi, are iconic examples of Georgian craftsmanship. These ornate structures, featuring latticework and intricate carvings, add charm and character to the city’s traditional homes.

- The interiors of Georgian churches often include elaborately carved wooden altars, iconostases, and pulpits, reflecting the skill and devotion of local craftsmen.

Metalwork and Enamel Art

Georgia’s metalworking traditions are deeply rooted in history, with artisans creating exceptional works in gold, silver, and bronze.

- Cloisonné Enamel:

- Georgian cloisonné enamel art, known as minankari, is a signature craft dating back to the early medieval period. This technique involves filling patterns outlined in metal with colored enamel, resulting in vibrant and durable designs.

- Minankari is often used to create religious icons, crosses, and jewelry, such as necklaces and brooches.

- Traditional Jewelry:

- Georgian jewelry, particularly from regions like Kakheti and Svaneti, features intricate designs that blend Byzantine, Persian, and local influences. Gold and silver pieces often include gemstone inlays and filigree work.

Ceramics and Pottery

Ceramic art has long been a cornerstone of Georgian craftsmanship, with potters creating both practical and decorative items.

- Wine Vessels:

- Georgia, often called the “cradle of wine,” has a rich tradition of pottery related to viticulture. The kvevri, a large clay vessel used for fermenting and storing wine, is an essential element of Georgian winemaking and a symbol of the country’s cultural heritage.

- Decorative Pottery:

- Georgian ceramics include plates, bowls, and tiles adorned with colorful glazes and patterns. These items often feature motifs inspired by nature and religious themes.

Themes and Motifs in Georgian Folk Art

Folk art in Georgia is characterized by recurring themes that reflect the nation’s identity and values:

- Connection to Nature: Designs often incorporate plants, animals, and celestial patterns, symbolizing the harmony between humanity and the natural world.

- Spirituality: Religious motifs, such as crosses and grapevines, appear frequently in textiles, metalwork, and wood carvings, reflecting Georgia’s deep Orthodox Christian faith.

- Regional Diversity: Each region of Georgia has its own distinct artistic traditions, from the bold rugs of Tusheti to the intricate jewelry of Svaneti.

Folk Art in Modern Times

While industrialization and modernization have changed the way many traditional crafts are practiced, Georgian folk art remains a vital part of the nation’s cultural identity.

- Revival and Preservation:

- Organizations and cultural institutions have worked to preserve Georgian folk art, offering workshops and exhibitions to keep traditional techniques alive.

- Artisans in rural areas continue to produce handmade items, often combining ancient techniques with modern designs.

- Integration into Contemporary Art:

- Many contemporary Georgian artists draw inspiration from folk traditions, incorporating motifs and techniques into their work. For example, the minankari enamel technique has been adapted to create modern jewelry pieces that appeal to global markets.

Themes of Folk Art and Craftsmanship

The enduring appeal of Georgian folk art lies in its ability to connect the past with the present:

- Resilience Through Art: Folk traditions have preserved Georgia’s cultural identity through centuries of upheaval.

- A Celebration of Everyday Life: Many folk art forms, from pottery to textiles, reflect the beauty and meaning of daily life in Georgia.

- Innovation Rooted in Tradition: Georgian artisans continue to evolve their craft, ensuring that these traditions remain vibrant and relevant in the modern world.

As we’ve seen throughout this exploration of Georgian art, the nation’s creative legacy is a testament to its resilience, adaptability, and cultural pride. In the final chapter, we’ll reflect on the enduring legacy of Georgian art and its place in the broader context of global artistic traditions.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Georgian Art

The history of Georgian art is a rich tapestry woven with threads of resilience, spirituality, and creativity. From the ancient petroglyphs of Trialeti to the contemporary installations of today’s avant-garde artists, Georgian art reflects a nation that has embraced change while fiercely preserving its identity. Positioned at the crossroads of civilizations, Georgia has absorbed influences from Byzantium, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, and Russia, yet its art remains unmistakably its own.

A Journey Through Georgian Art

Georgian art has evolved over millennia, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire:

- Prehistoric Foundations: The earliest artistic expressions, including rock carvings and bronze artifacts, reveal the ingenuity and spirituality of Georgia’s ancient peoples.

- Christianization and Medieval Splendor: The adoption of Christianity in the 4th century catalyzed a golden age of religious art and architecture, producing masterpieces such as the frescoes of Vardzia and the cloisonné enamel of the Khakhuli Triptych.

- Cultural Adaptation Under Empires: During centuries of Persian and Ottoman influence, Georgian artists blended foreign styles with local traditions, ensuring their culture’s survival.

- Modernism and Soviet Challenges: Georgian artists like David Kakabadze and Lado Gudiashvili pushed boundaries, navigating the constraints of Socialist Realism while finding ways to celebrate their heritage.

- Contemporary Innovation: Today’s artists, from Tamara Kvesitadze to the Bouillon Group, continue to redefine Georgian art, exploring themes of identity, globalization, and the human condition.

Recurring Themes in Georgian Art

Throughout its history, Georgian art has been unified by key themes:

- Faith and Spirituality: Art has long been a medium for expressing Georgia’s deep Orthodox Christian faith, from frescoes to wooden church carvings.

- Connection to Nature: Whether through patterns in textiles, motifs in metalwork, or landscapes in painting, Georgian art celebrates the beauty and symbolism of its environment.

- Cultural Resilience: Georgian art has served as a means of preserving identity, with artists often using their work to reflect national pride and resist foreign domination.

A Global Perspective

Today, Georgian art stands as a bridge between past and present, local and global. Institutions like the Georgian National Museum and events like the Tbilisi Art Fair connect Georgia’s artistic heritage to the wider world, showcasing its unique voice in the global art community. Meanwhile, contemporary artists draw inspiration from their cultural roots to address universal themes, ensuring that Georgian art continues to resonate beyond its borders.

Looking Forward

As Georgia continues to navigate its place in the modern world, its art remains a vital expression of its identity and aspirations. The legacy of Georgian art is not merely a reflection of its past but a dynamic force shaping its future. Whether through the intricate patterns of a Tushetian rug, the bold lines of a modern painting, or the striking form of a kinetic sculpture, Georgian art tells a story of creativity, endurance, and hope.