Frida Kahlo was born on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico, a quiet neighborhood just outside of Mexico City. Her full name was Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón. Though born into relative comfort—her father Guillermo was a German-Mexican photographer—her life would be anything but easy. Even from an early age, suffering seemed to follow her, shaping her personality and, later, her unique artistic voice.

At the age of six, Frida contracted polio, which left her right leg thinner and weaker than the left. This illness caused her to limp, and children often bullied her, leading to a sense of isolation. Her father, noticing her distress, encouraged her to engage in physical activities like swimming, bicycling, and wrestling—unusual pastimes for girls at the time. These efforts helped her regain some strength, but the damage to her body was permanent and set the stage for more severe health issues later in life.

Frida’s destiny took a brutal turn on September 17, 1925, when the bus she was riding in collided with a streetcar in downtown Mexico City. She suffered horrific injuries, including a shattered pelvis, a fractured spine, broken ribs, a dislocated shoulder, and a metal handrail that impaled her abdomen and exited through her vagina. Doctors doubted she would survive, but after multiple surgeries and months of immobility, she endured. This trauma would leave her in chronic pain for the rest of her life and deeply influence her art, making her own suffering a central subject of her work.

While recovering in bed, Kahlo began painting, using a special easel that allowed her to work while lying down. She painted her first self-portrait in 1926 and discovered that art offered a means to express the pain and solitude she lived with daily. In 1929, she married famed muralist Diego Rivera. Their tumultuous relationship, marked by infidelity and emotional volatility, would bring both inspiration and additional heartache. Despite all odds, Frida built a legacy rooted in resilience, creativity, and an unflinching gaze into the rawest corners of the human experience.

Anatomy as Allegory: Kahlo’s Body on Canvas

Frida Kahlo’s paintings were not just portraits; they were deeply layered visual allegories of her internal world. Her medical history became a symbolic language, etched into every canvas with vivid, often grotesque detail. Rather than shy away from the discomfort of her body, she placed it at the center of her work. Her anatomical accuracy served not only as a record of her injuries but also as a metaphor for the burdens women carry, both physically and emotionally.

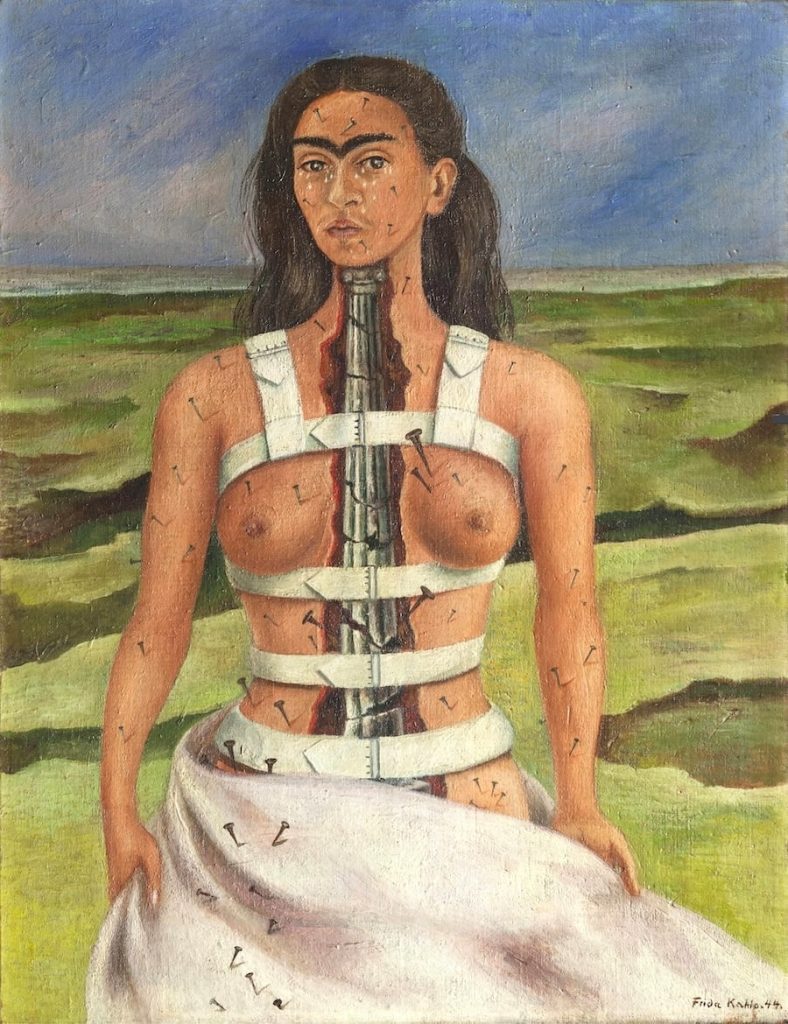

One of the most iconic examples of this is The Broken Column (1944), where she depicts herself with a split torso, revealing a shattered ionic column in place of her spine. Tears run down her face, nails pierce her body, and a steel corset holds her broken form together. It’s not just a depiction of physical agony—it’s a spiritual and psychological dissection. In Henry Ford Hospital (1932), she paints herself lying in a pool of blood, connected by red veins to a fetus, pelvis, snail, and mechanical tools, symbolizing her miscarriage and helplessness.

Kahlo’s paintings blend anatomical realism with surrealism, creating a style that is both intimate and disturbing. Her self-portraits often show her open, wounded, or bound in medical devices. Unlike the traditional beauty-focused portraits of her time, Frida made visible what others concealed. The blood, bandages, surgical scars, and steel corsets became her visual vocabulary, challenging notions of femininity and idealized bodies.

This allegorical use of anatomy allowed Kahlo to reframe suffering as endurance, and trauma as testimony. Her body, broken and repaired countless times, became a battlefield where identity, culture, and womanhood clashed. She wasn’t just recording medical history—she was rewriting what it meant to be a woman in pain, in love, and in art. Her work doesn’t whisper; it screams truths many would rather not hear.

The Bus Accident: A Catalyst for Medical Obsession

On that fateful day in September 1925, Frida Kahlo’s life changed forever. She was just 18 years old when the wooden bus she and her boyfriend Alejandro Gómez Arias were riding collided with an electric streetcar. The crash was horrific—metal handrails impaled several passengers, and Frida was among the worst injured. Her spinal column broke in three places, her collarbone was fractured, and her foot was crushed and dislocated.

She also suffered eleven fractures in her right leg, a broken pelvis, and her uterus was punctured, making future pregnancies extremely difficult. The doctors initially believed she wouldn’t survive. Over the next several months, Frida underwent numerous surgeries to stabilize her condition. As she lay immobile in a plaster cast, her parents installed a mirror above her bed so she could paint self-portraits—a therapeutic act that sparked her lifelong relationship with art.

Her first self-portraits emerged during this recovery period, blending personal introspection with visual symbolism. These early works reveal a young woman grappling with her own mortality and body betrayal. She turned to the canvas to make sense of the violence her body had endured. Over time, her paintings would evolve into a deeply personal form of medical storytelling, chronicling the ongoing consequences of the accident.

This trauma set the stage for a lifetime of operations, including spinal fusions, amputations, and grueling therapy. But it also gave her work a sense of urgency and honesty that few artists possess. She wasn’t painting to please critics—she was painting to survive. The bus accident may have mangled her bones, but it also ignited her creative fire, which would burn until her death in 1954.

Miscarriages and Motherhood in Medical Metaphor

One of the most heartbreaking themes in Kahlo’s work is her inability to have children. As a young woman, she longed for motherhood, a desire that was consistently thwarted by her damaged reproductive organs and chronic illness. Her accident had left her uterus severely injured, and despite several attempts, she suffered at least three miscarriages. Each loss was devastating, and she translated that grief into some of her most haunting paintings.

In Henry Ford Hospital (1932), she depicts herself on a blood-soaked hospital bed after a miscarriage, surrounded by floating symbols: a fetus, pelvic bones, a snail, a flower, and medical instruments. The red veins connecting them to her body represent both physical and emotional ties. Her exposed anatomy and blank stare reflect both pain and helplessness. This piece doesn’t just show loss; it shows how deeply that loss embeds itself in the body.

Another painting, My Birth (1932), shows a surreal and disturbing image of a baby being born from a shrouded figure, with Kahlo’s own adult face emerging from the mother’s body. It suggests a cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, blurring the boundaries between mother and daughter, life and loss. The painting’s frank treatment of female anatomy and birth was shocking for the time—and still is. Frida redefined motherhood not by bearing children, but by giving life to emotional truth through art.

Kahlo also infused these images with Mexican cultural symbols, mixing Catholic martyrdom with Aztec fertility icons. She painted herself as both creator and sufferer, mirroring ancient traditions while speaking to her own modern sorrow. Her inability to bear children didn’t make her less of a woman—it made her more of an artist. By transforming miscarriage into metaphor, she turned silence into expression and pain into permanence.

Surgery, Scars, and the Ritual of Recovery

Over her lifetime, Frida Kahlo endured more than 30 surgeries—many of them brutal, invasive, and ultimately unsuccessful. From spinal fusions to bone grafts and even a leg amputation, her body became a surgical battlefield. Her medical journey was not linear but cyclical: one operation leading to another, each promising relief that never quite came. This endless return to the operating table became a ritual of both destruction and hope, and she captured that in her visual language.

In The Broken Column, she paints herself with her torso cracked open, exposing a crumbling classical column in place of her spine. Steel corsets bind her body, while nails pierce her skin—each one representing a specific pain. Her gaze is steady, unflinching, as tears stream down her cheeks. The piece is less a cry for help than a solemn record of endurance, a sacred icon of survival through suffering.

Her paintings also feature hospital beds, IV drips, and medical tools—turning what most see as sterile objects into symbols of emotional violation. In Tree of Hope, Remain Strong (1946), she paints two versions of herself: one lying bloodied on a surgical gurney, the other sitting upright in traditional Tehuana dress, holding a corset and a flag that reads “Tree of Hope, Remain Strong.” This duality reflects her internal conflict: the physical decay of her body versus the resilience of her spirit.

Kahlo’s work reveals how surgery wasn’t just physical—it was spiritual. Raised Catholic, she often depicted herself in poses reminiscent of saints or martyrs. Her suffering became ritualistic, echoing religious iconography. The operating room replaced the chapel; surgical scars became sacred stigmata. In this way, Frida Kahlo redefined the very act of recovery—not as a return to normalcy, but as a transformation of self through suffering.

Diego Rivera’s Role: Love, Betrayal, and Medical Witness

Frida Kahlo married Diego Rivera on August 21, 1929. He was twenty years older, already a celebrated muralist, and famously difficult. Their marriage was a tempest—rich in passion but marred by repeated infidelities, including one particularly painful affair with Frida’s own sister, Cristina. Yet despite all this, their relationship remained one of the most influential and complex unions in art history.

Diego was more than a husband—he was a collaborator and, during her medical crises, a caregiver. He helped pay for her many surgeries and often stayed by her bedside during long recoveries. However, his emotional instability and serial unfaithfulness inflicted deep psychological wounds on Frida. These betrayals became recurring motifs in her artwork, often interwoven with images of physical pain.

In Diego and I (1949), Frida paints herself with tears streaming down her face, Rivera’s face embedded in her forehead—a symbol of how he haunted her thoughts. The emotional turmoil in their relationship spilled over into her paintings, blurring the line between love and torment. Another example, A Few Small Nips (1935), inspired by a newspaper story of a murdered woman, channels her rage and heartbreak into a violent metaphor for betrayal. She equated Rivera’s unfaithfulness to emotional mutilation.

Despite all of this, Frida and Diego remarried in 1940 after a brief divorce. Their second union was calmer but still complex. Diego never stopped being a source of inspiration—and of sorrow. He admired her fiercely, calling her art “the most authentic expression of the Mexican soul.” Yet his presence remained both a balm and a wound, another contradiction in a life full of them.

Legacy of Pain: Frida’s Influence on Modern Art and Identity

Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, at the age of 47. Her death marked the end of a life filled with suffering, but the beginning of a legacy that would only grow with time. Though she was not widely recognized internationally during her lifetime, her work surged in popularity in the decades following her death. Today, her face is instantly recognizable, and her influence on modern art, identity politics, and cultural resilience is immeasurable.

Kahlo’s raw portrayal of disability, chronic pain, and womanhood has inspired countless artists, particularly those grappling with their own physical or emotional struggles. Her work is studied not just in art schools but also in medical humanities courses for its ability to humanize suffering. The disabled community has embraced her as a pioneer who portrayed medical experiences with dignity and force. Feminists, too, have found in her a symbol of strength amid fragility.

Her Blue House in Coyoacán was turned into a museum in 1958, and her work now hangs in prestigious institutions like the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Tate Modern in London. Exhibitions of her art often break attendance records. Her likeness and themes have been adapted by fashion designers, filmmakers, and even toy companies—sometimes to the dismay of those who see such commodification as contrary to her spirit.

Yet even amid this modern embrace, her core message endures: the truth of the human body, in all its beauty and agony, is worth telling. Kahlo did not paint for fame or fortune—she painted to survive, to remember, and to be remembered. In that way, every scar she bore has become part of a shared human story. Her art continues to speak because it was always honest, always brave, and always painfully real.

Key Takeaways

- Frida Kahlo used her traumatic medical history as the foundation for her artistic voice.

- Her paintings depict anatomical detail, chronic pain, and emotional suffering with brutal honesty.

- The 1925 bus accident left her with lifelong injuries that became central themes in her work.

- Her relationship with Diego Rivera was both creatively fruitful and personally devastating.

- Kahlo’s legacy influences modern artists, especially in themes of disability, womanhood, and endurance.

FAQs

- When was Frida Kahlo born and when did she die?

Frida was born on July 6, 1907, and died on July 13, 1954. - How many surgeries did Frida Kahlo undergo in her lifetime?

She endured more than 30 surgeries, including spinal fusions and a leg amputation. - What caused Frida Kahlo’s major injuries?

A 1925 bus accident left her with multiple fractures and internal injuries. - Did Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera stay married?

They married in 1929, divorced in 1939, and remarried in 1940. - Why is Kahlo considered a symbol of resilience?

Her art turned chronic suffering into a legacy of strength, identity, and truth.