The Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, known in Swedish as Kungliga Akademien för de fria konsterna, traces its roots back to 1735 when it was first founded as the Royal Drawing Academy. The initiative came during the reign of King Frederick I of Sweden, who aimed to bolster national culture and elevate the standing of Swedish art on the European stage. At the time, artistic training in Sweden was largely informal, often passed from master to apprentice with no structured education. The Academy was seen as a solution to bring formal academic instruction to talented Swedes, while also keeping pace with leading art centers like Paris and Rome.

Official royal status was granted in 1773 by King Gustav III, a monarch known for his deep appreciation of the arts and culture. Gustav III was influenced by the French Enlightenment and sought to modernize Sweden through intellectual and artistic progress. By giving the Academy its royal designation, he affirmed its national importance and ensured state support for generations to come. This royal patronage also elevated the Academy to a symbol of prestige, placing it alongside Europe’s most respected institutions.

Among the key figures behind the Academy’s foundation was Carl Gustaf Tessin (1695–1770), a noted art collector, diplomat, and politician. Tessin’s enthusiasm for art and his influential role in Swedish politics made him instrumental in shaping the Academy’s early direction. He believed that Sweden needed a centralized institution to cultivate domestic talent and reduce dependence on foreign artists. Tessin’s vast art collection, which included works from Rembrandt and other European masters, later contributed to the development of Sweden’s national art collections.

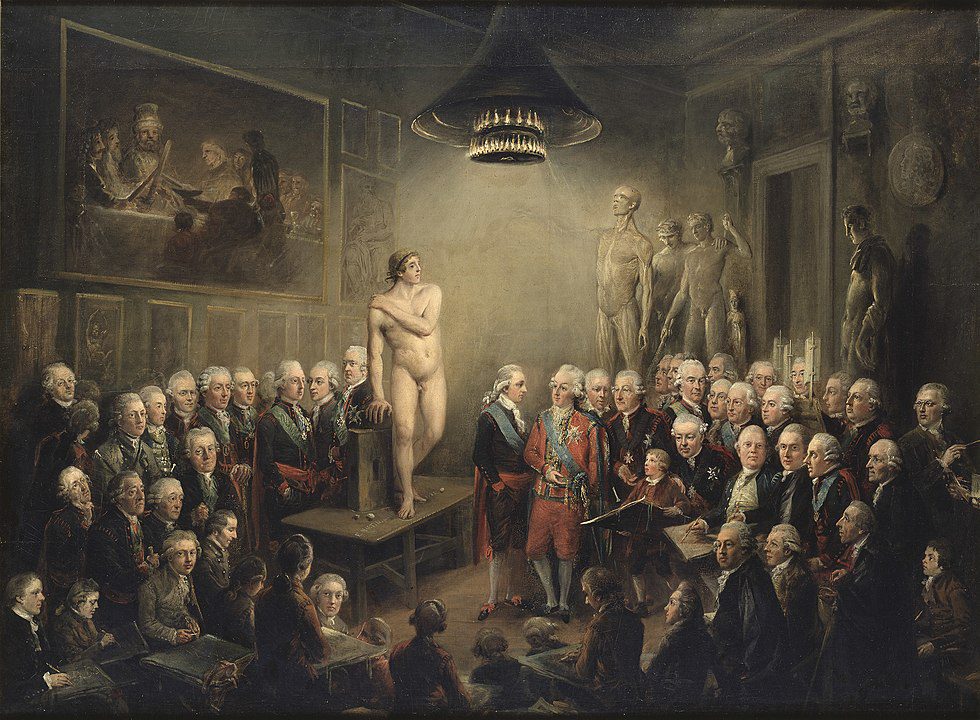

The Academy also benefited from early professors who helped set academic standards and curriculum. One of the earliest was Johan Pasch (1706–1769), a court painter who became the first director of the Academy. Pasch was known for his Rococo-style works and had studied in Paris, bringing continental technique and style back to Sweden. He helped establish a foundation of classical art training that emphasized drawing from live models, anatomical studies, and copying from Old Masters. These values remained embedded in the Academy’s ethos for centuries.

Evolution Through the Centuries

As the 19th century unfolded, the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts underwent significant transformations that mirrored the broader cultural shifts across Europe. In the early 1800s, the Academy began adjusting its teaching to incorporate Romantic ideals, which emphasized individual expression and emotional depth. This period saw an increased focus on history painting, portraiture, and grand narratives, responding to both national pride and artistic trends. The Swedish state also began to use the Academy to support public art projects, encouraging patriotism through grand murals and sculptures.

During the late 1800s and into the early 1900s, the Academy had to reckon with the rise of modernism and a growing movement against academic conservatism. Many younger artists began to challenge the classical methods taught at the Academy, seeking instead freedom of expression and experimentation. The Academy found itself caught between preserving tradition and adapting to change. Debates over realism, impressionism, and symbolism began to reshape how students and faculty approached the creative process.

One major educational reform came during the 1930s and 1940s, when the Academy responded to global political upheaval and a new wave of artistic innovation. Influential architect and professor Gunnar Asplund (1885–1940), known for designing the Woodland Cemetery (Skogskyrkogården), played a critical role in modernizing architectural instruction at the Academy. Asplund’s modernist principles encouraged students to embrace simplicity, functionality, and new materials—moving beyond neoclassical design. His impact bridged traditional craftsmanship with a fresh, progressive vision for the built environment.

The post-World War II era brought further modernization, with a strong focus on abstraction, conceptual art, and interdisciplinary approaches. By the 1960s and 1970s, the Academy opened its doors to avant-garde practices and began collaborating with international artists. Curriculum reforms expanded to include photography, performance art, and installation. These changes allowed the Academy to remain relevant in a globalized art world while still honoring its historical legacy.

The Academy Building and Its Cultural Significance

Nestled in the heart of central Stockholm, the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts is housed in a historic building located at Fredsgatan 12. Originally constructed as a private palace in the 17th century, the structure was later adapted to serve the Academy’s needs in the late 18th century. With its neoclassical façade and grand interior halls, the building exudes timeless elegance and intellectual gravity. The architecture itself is a visual statement of the Academy’s stature in Swedish society.

One of the most significant contributors to the design and evolution of the building was Fredrik Blom (1781–1853), a military officer and renowned architect. Blom’s involvement in the early 1800s helped transform the building into a fully functional space for both education and exhibition. His structural innovations and clean design principles added functionality without compromising aesthetic appeal. He prioritized natural light, spacious studios, and efficient circulation, making the space ideal for aspiring artists.

Throughout the centuries, the building has undergone several renovations to accommodate changing needs and technologies. In the 1990s, a major restoration project modernized the building’s infrastructure while preserving its historical character. The goal was to retain the building’s original features—such as vaulted ceilings, marble staircases, and frescoes—while upgrading heating, lighting, and accessibility. Today, the building blends historical grandeur with contemporary usability, providing a hub for education, exhibitions, and administration.

The Academy’s building is not just a functional space; it’s a national treasure and a beacon of Sweden’s artistic tradition. It regularly hosts major exhibitions, lectures, and award ceremonies, bringing together students, scholars, and the general public. Tourists and locals alike are drawn to its architectural charm and cultural offerings. As a result, Fredsgatan 12 is more than a school—it is a landmark that embodies the intersection of history, art, and civic pride.

Artistic Education and Training at the Academy

From the beginning, the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts has prioritized rigorous artistic training grounded in classical principles. In the 18th and 19th centuries, students studied disciplines like painting, sculpture, and architecture, focusing heavily on drawing from life and understanding human anatomy. The curriculum emphasized discipline, skill, and theory, mirroring French and Italian academic models. Artistic training was not just technical but also philosophical, encouraging students to explore beauty, balance, and moral themes.

Over time, the Academy diversified its approach to include new artistic movements and materials. By the early 20th century, modern art began influencing instruction, prompting the inclusion of color theory, abstraction, and expressionism. Students could still study classical portraiture and landscape painting, but they were also exposed to the bold visual language of cubism, fauvism, and surrealism. These expansions allowed students to develop a personal style while maintaining a solid technical foundation.

Among the Academy’s most celebrated alumni is Anders Zorn (1860–1920), whose remarkable portraits and mastery of watercolor earned him international acclaim. Zorn studied at the Academy starting in 1875 and went on to paint U.S. Presidents and Swedish royalty. Another influential graduate, Bruno Liljefors (1860–1939), became famous for his dynamic wildlife paintings, combining scientific observation with artistic flair. And in more recent years, Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), a trailblazing abstract artist, has received global recognition—though her spiritual, visionary works went largely unrecognized during her lifetime.

Mentorship and public exhibitions have long been cornerstones of the Academy’s educational model. Senior artists, professors, and alumni guide students not only in technique but also in navigating the art world. The Academy regularly holds student exhibitions, giving young artists a platform to showcase their work to critics, collectors, and the general public. This approach fosters confidence, professionalism, and a sense of continuity with Sweden’s long artistic tradition.

Famous Members and Partnerships Through the Years

Membership in the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts is considered one of the highest honors for artists in Sweden. Only the most accomplished painters, sculptors, architects, and art historians are elected, with selections made through peer nomination and rigorous review. These members not only serve as mentors and jurors but also help shape public policy on arts funding and education. Their influence extends beyond the Academy’s walls and into the cultural fabric of the nation.

Several prominent artists have left their mark as members. Carl Larsson (1853–1919), known for his idyllic depictions of Swedish domestic life, was a beloved figure whose membership helped elevate the Academy’s profile in the early 20th century. Eugène Jansson (1862–1915), famous for his deep blue nocturnes of Stockholm, was also a member whose work bridged realism and symbolism. In the 1920s and 1930s, Isaac Grünewald (1889–1946) became a key figure, known for his colorful, expressionistic paintings and leadership in modern art education.

The Academy has long maintained fruitful partnerships with other European institutions, fostering cross-cultural exchange and innovation. Its historical ties to the French Royal Academy and later interactions with schools in Germany and Italy enriched its curriculum and broadened student exposure. Exchange programs and residencies enabled Swedish artists to study abroad, while welcoming international figures to Stockholm. This ongoing collaboration kept the Academy attuned to global trends while remaining grounded in national identity.

Public commissions have also been a significant aspect of the Academy’s legacy. Members have often been chosen to design and execute national monuments, murals in state buildings, and works celebrating Swedish heritage. From the sculptures in Stockholm’s city center to frescos in government halls, Academy-trained artists have shaped the aesthetic of public space. These projects not only showcase artistic excellence but also reflect the Academy’s central role in Sweden’s cultural development.

Exhibitions, Events, and Public Engagement

Beyond education and membership, the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts plays an active role in the broader public sphere through its exhibitions and events. Its galleries on Fredsgatan are open to the public year-round, showcasing everything from student showcases to retrospectives of major Swedish artists. These exhibitions often include paintings, sculptures, installations, and multimedia works that reflect the depth and diversity of the Academy’s talent. Visitors gain a firsthand look at both emerging voices and celebrated masters.

One of the Academy’s most anticipated annual events is the Konstnärlig vårsalong, or Spring Art Salon. This juried exhibition invites artists of all ages and styles to submit work, promoting inclusivity and artistic dialogue. The Spring Salon draws large crowds and serves as a launching pad for young artists hoping to gain recognition. It’s also a chance for seasoned collectors and critics to scout new talent, reinforcing the Academy’s role as a tastemaker.

Public lectures and award ceremonies form another critical pillar of the Academy’s outreach. The Duke Eugen Medal, established in 1945 in memory of Prince Eugen, honors exceptional contributions to the arts. Past recipients have included architects, painters, designers, and sculptors whose work embodies both innovation and tradition. These ceremonies highlight the Academy’s commitment to celebrating excellence and preserving Sweden’s cultural heritage.

The Academy actively collaborates with schools, community organizations, and art institutions to bring art to the wider population. Programs for children, workshops for educators, and community-based exhibitions ensure that art is not reserved for the elite. Through these initiatives, the Academy strengthens civic pride, encourages creativity, and reinforces the idea that art is essential to a healthy society. It is a living institution—deeply rooted in history yet vibrantly connected to the present.

Legacy and the Academy in the Modern Era

Today, the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts remains a cornerstone of Swedish cultural life, balancing its rich traditions with a modern mission. Its headquarters still host artist studios, offices, and public galleries, while its members participate in debates about the role of art in a changing society. With an eye on both preservation and progress, the Academy continues to nurture talent and serve as a guardian of national artistic standards. Despite the ever-evolving landscape of contemporary art, its core values of excellence, discipline, and cultural stewardship endure.

Leadership at the Academy has embraced modern technologies and digital platforms to expand its reach. Online exhibitions, artist talks, and interactive educational content now complement its in-person programming. This shift has allowed the Academy to connect with younger audiences, rural communities, and international viewers who may not visit Stockholm in person. By leveraging digital tools, the institution remains relevant without compromising its integrity.

Contemporary members of the Academy reflect a wide spectrum of artistic practices—from traditional oil painters to digital media innovators. Their diversity demonstrates the Academy’s openness to evolution while maintaining high standards. Active participation in policy discussions, cultural funding, and urban planning ensures that art remains central to Sweden’s development. The Academy is not a relic; it is a dynamic institution shaping both artists and society.

Looking ahead, the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts is poised to continue its mission of inspiring excellence, preserving heritage, and advancing culture. Its legacy is visible not only in museums and public monuments but also in the creative spirit of generations of Swedish artists. As society faces new challenges, from digital disruption to cultural polarization, the Academy offers a grounded, principled voice. Through its programs and people, it embodies the belief that art can elevate the soul and strengthen a nation.

Key Takeaways

- The Academy was founded in 1735 and gained royal status in 1773 under King Gustav III.

- Key members include Anders Zorn, Carl Larsson, Hilma af Klint, and Isaac Grünewald.

- The Academy building at Fredsgatan 12 is a historical and cultural landmark in Stockholm.

- Events like the Spring Art Salon and Duke Eugen Medal keep the Academy publicly engaged.

- The institution remains influential in shaping Sweden’s art and cultural policy.

Frequently Asked Questions

- When was the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts founded?

It was originally founded in 1735 as the Royal Drawing Academy. - Where is the Academy located?

It is housed in a historic building at Fredsgatan 12 in central Stockholm. - Who are some notable alumni?

Notable alumni include Anders Zorn, Hilma af Klint, Bruno Liljefors, and Carl Larsson. - Does the Academy host public exhibitions?

Yes, it regularly hosts exhibitions, lectures, and events open to the public. - What is the Duke Eugen Medal?

It’s an annual award established in 1945 honoring outstanding contributions to the arts.