Eva Mudocci was born Evangeline Hope Muddock in 1872 in England, into a family with literary and artistic leanings. Her father, J. E. Preston Muddock, was a prolific journalist and author of popular detective fiction. Eva’s upbringing in a cultured, expressive household likely helped shape her artistic sensibility from a young age. By her teenage years, she had already shown remarkable talent as a violinist and began to build a reputation across the British musical world.

Her stage name, “Mudocci,” was adopted during her early career to lend a Continental flair — a common practice among performers seeking greater appeal on the European stage. She partnered with pianist Bella Edwards in the 1890s, forming a highly praised duo. The pair toured extensively across Europe in the early 20th century, performing in cities like Berlin, Paris, and Vienna. Reviews from the time frequently praised Mudocci’s elegant technique and emotional depth, describing her playing as both refined and passionate.

Mudocci’s beauty and fashion sense also caught public attention. She was known for her graceful stage presence, and newspapers often described her as “striking” or “modern,” both in her appearance and in the tone of her music. While she never reached the international superstardom of contemporaries like Fritz Kreisler or Eugène Ysaÿe, she was nonetheless a respected and sought-after performer in elite concert circuits. By the time she met Edvard Munch, she had already solidified her place within the cultural elite of Europe’s artistic capitals.

Her close companionship with Bella Edwards went beyond the stage. The two lived and traveled together for over two decades, and historical consensus now widely accepts theirs as a long-term lesbian partnership. Though such relationships were rarely spoken of openly in Edwardian society, theirs was an enduring bond that influenced every aspect of Mudocci’s life — including her fateful connection with Edvard Munch.

Meeting Munch: When Music and Painting Collide

Eva Mudocci and Edvard Munch met in 1903, most likely in Berlin, though some accounts suggest their paths may have crossed earlier in Paris. By this time, Munch had gained widespread attention in the art world for his emotionally raw paintings such as The Scream (1893), Madonna (1894–95), and Ashes (1894). He was already notorious for his intense personality and for his difficult, sometimes obsessive relationships with women. Mudocci, poised and disciplined, was in many ways his opposite — and perhaps that contrast is what drew him in.

Munch had spent the previous years immersed in the Symbolist and Secessionist movements, exhibiting widely in Berlin, where avant-garde circles embraced his work. Berlin was also where Mudocci and Edwards frequently performed, often to full houses and glowing reviews. The two worlds — visual and musical — overlapped in the salons and studios of the city’s intellectual elite. Munch had always been fascinated by musicians, especially women whose art involved performance and interpretation. Mudocci’s appearance in his life represented both a fresh subject and a psychological enigma.

What happened between them in 1903 left a deep impression on Munch. Though details are scarce, what is known is that he completed a powerful lithographic portrait of her that same year. This was no quick sketch or idle tribute — it was a considered work of high emotional tension, one that stood apart from many of his earlier portrayals of women. Mudocci had entered not just his life, but his creative imagination.

Their meetings seem to have been intense but limited to a relatively short period, spanning late 1903 into perhaps 1904. According to some biographers, they spent several weeks together in Copenhagen and Berlin, during which time Munch is said to have experienced bouts of jealousy, frustration, and creative inspiration. The presence of Bella Edwards — always nearby, always in control — may have contributed to the emotional complexity of their interactions. Munch, never emotionally stable in matters of intimacy, seemed captivated and destabilized by Mudocci’s serene presence.

The Brooch: Munch’s Portrait of a Mystery

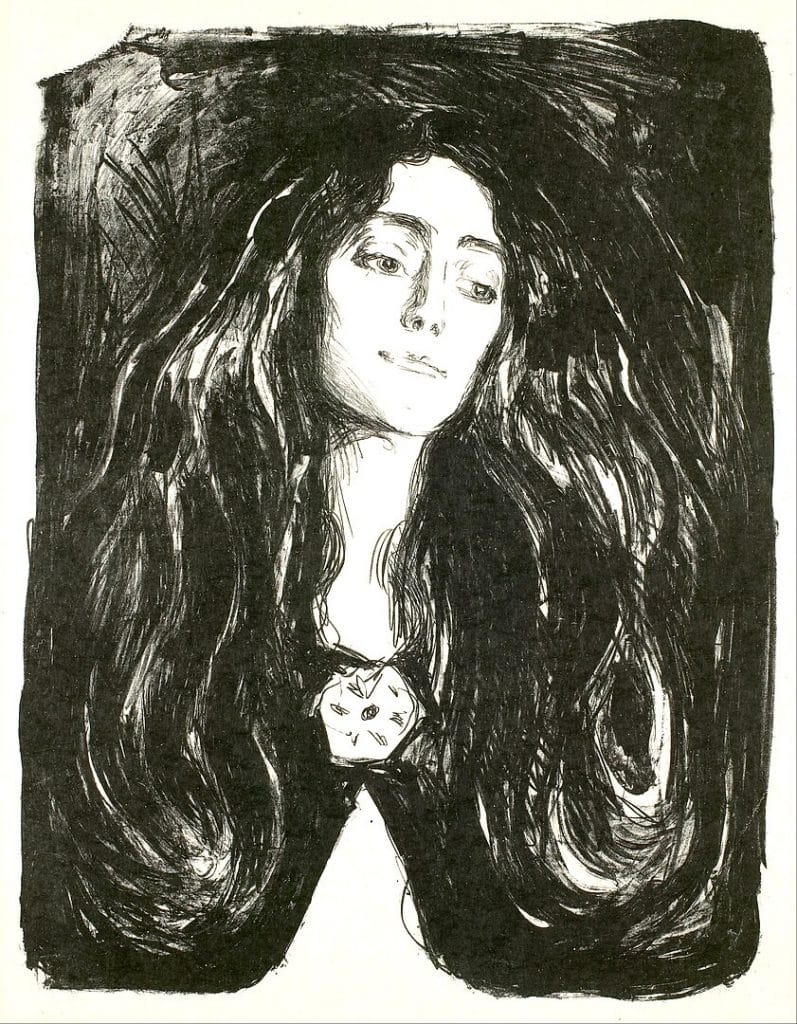

Among the many portraits created by Edvard Munch, The Brooch. Eva Mudocci remains one of the most enigmatic. Completed in 1903, the black-and-white lithograph shows Mudocci with her head slightly tilted, her dark hair flowing loosely over her shoulders. The most arresting feature is the stark white brooch at her throat — a glowing point of contrast in a composition otherwise drenched in shadow. Her expression is unreadable: calm, withdrawn, almost mournful.

The style of the portrait marks a shift in Munch’s approach. Where earlier female figures such as the Madonna or the women in Puberty (1895) are rendered with overt symbolism or overt emotional distress, Mudocci is presented with restraint. There is no background, no visual noise. She seems suspended in a void, a modern woman untouched by traditional tropes of virtue or vice. Munch’s decision to focus so intently on her face — and on the symbolic brooch — suggests an obsession with presence, rather than narrative.

Art historians have long noted the differences between The Brooch and other Munch works. Whereas many of his portraits of women are emotionally turbulent, often hinting at madness, sin, or erotic agony, Mudocci’s portrait is still. Some scholars interpret the image as a meditation on distance — a woman admired but never possessed. Others have called it Munch’s only true portrait of a woman he could not break or idealize. The brooch itself may symbolize her self-possession — a token of elegance, untouched by the chaos Munch so often infused into his art.

The work is held today at the Munch Museum in Oslo and remains one of the most analyzed female portraits in his entire body of work. In exhibitions, it is often displayed alongside his other depictions of women, where its quiet power and stark simplicity stand out. Mudocci, rendered in ink and shadow, has become an icon of early modernist portraiture — not through drama or symbolism, but through the haunting silence of her gaze.

- Key features of The Brooch:

- Composed in 1903, black-and-white lithograph

- Strong contrast between dark hair and luminous brooch

- Calm, introspective facial expression

- Absence of background details, emphasizing emotional isolation

Muse or More? Exploring Their Relationship

The emotional intensity of Munch’s art often reflected the turmoil of his personal life. With Eva Mudocci, that emotional landscape becomes harder to read. Unlike other women who were part of Munch’s life — such as Tulla Larsen, whose broken engagement left the artist devastated — Mudocci seemed to exist at a remove. Their relationship, if it included romance or physical intimacy, was brief and remains undocumented in any surviving personal letters or diaries. Yet the depth of her impact on Munch’s work suggests something more than a passing encounter.

Contemporaneous accounts from Munch’s friends describe his behavior during the period of his meetings with Mudocci as increasingly erratic. Some speculate that she triggered in him a sense of longing that he could not reconcile with his fear of commitment. Mudocci’s controlled and disciplined persona may have amplified Munch’s own instability. She did not fit easily into the roles he assigned to other women — there was no betrayal, no madness, no overt sexuality. Only stillness, restraint, and the unsettling presence of the unknowable.

The portrait he made of her — The Brooch — may have served as both tribute and closure. After 1904, there is no evidence that the two remained in close contact, though Mudocci would later speak of Munch with a kind of quiet pride. She did not deny the importance of their encounter, but she also did not dwell on it. Unlike many of Munch’s other romantic entanglements, which ended in dramatic public scenes or bitter correspondence, this one simply faded — a fire that left smoke but no ashes.

For Munch, the muse was often an emotional battleground. With Mudocci, he was denied that struggle. She remained distant, dignified, and perhaps that is what made her unforgettable. To Munch, who was drawn to extremes, Mudocci represented a woman who could not be bent to fit a narrative. She was not lost, not saved, and not his.

A Private Triangle: Bella Edwards and Hidden Affections

Bella Edwards was not merely Mudocci’s pianist — she was her partner in life as well as on stage. Born in 1876, Edwards began performing with Mudocci in the late 1890s. The two quickly became inseparable, both musically and personally. While their romantic relationship was never publicly confirmed in explicit terms, private correspondence, travel records, and interviews with contemporaries make it clear that they lived as a couple. In Edwardian Europe, such partnerships between women were not entirely unknown, though always spoken of in euphemisms or polite silence.

The strength of their bond complicates the story of Mudocci’s brief entanglement with Munch. It is quite possible that Munch was unaware of the full nature of their relationship, though he surely knew the women were always together. Alternatively, he may have understood it and hoped to override it — a notion not uncharacteristic of his personality. What is certain is that Bella Edwards remained Mudocci’s closest companion until her death in 1929.

Their tours across Europe were a showcase not only of musical talent but of emotional harmony. Edwards’ playing complemented Mudocci’s perfectly, and critics often remarked on the “almost telepathic” coordination between them. Behind the curtain, their life together was private, comfortable, and in many ways defiant of the expectations placed upon women in their time. In an age when same-sex relationships had to exist in code, theirs was both discreet and durable.

Mudocci’s relationship with Munch, while artistically significant, never displaced the central role that Edwards played in her life. Whether Munch knew it or not, he was part of a triangle in which he was the outsider. Mudocci’s ability to inspire great art did not mean she belonged to the artist — a fact that may have only deepened the portrait’s haunting intensity.

The Child Controversy: Was Mudocci the Mother of Munch’s Child?

In recent decades, a new dimension to Eva Mudocci’s connection with Edvard Munch has stirred controversy and curiosity alike. This centers around the theory that Mudocci gave birth to Munch’s child — a daughter — around 1908. The claim gained public attention in the 2010s when family descendants of a woman named Isobel came forward, asserting that she was the illegitimate child of Eva Mudocci and Edvard Munch. While the idea remains unproven, the timeline and circumstantial evidence have fueled continued speculation.

According to family accounts, Mudocci gave birth to twins in Denmark in 1908, one of whom was adopted. The other, Isobel, remained with Mudocci and was raised in a private, protective environment. The family narrative included whispers that the girl’s father was a “famous painter,” though no name was formally recorded. Isobel herself died in 1992, but her descendants later sought to validate the story through historical documentation and eventually, DNA testing. In 2012, they approached the Munch Museum in Oslo with a request to test biological material from the artist’s remains.

The museum declined the request, citing preservation concerns and the lack of conclusive historical documentation linking Mudocci to the pregnancy. Nevertheless, the theory gained traction in both the press and scholarly circles, especially after private letters and photographs emerged showing Mudocci with young children in the years following her public retreat from performance. These materials did not offer definitive proof, but they strengthened the possibility that she had become a mother — and that Munch may have been the father.

While no verifiable birth certificate naming Munch exists, the story has endured because it fits the emotional puzzle left behind. Munch was notoriously fearful of fatherhood and lifelong relationships. Mudocci, by contrast, withdrew into increasing privacy after 1908, suggesting a potential change in her life’s direction. Whether or not the story is true, the very existence of the claim has added a layer of human drama to a relationship already rich in artistic and emotional ambiguity.

Legacy in Silence: Mudocci’s Life After Munch

After her artistic and romantic peak in the early 1900s, Eva Mudocci gradually disappeared from public view. By 1911, her performance schedule had slowed dramatically, and by the end of World War I, she was no longer actively touring. Her decision to retire from the stage may have been influenced by personal changes, including the responsibilities of motherhood, if the child rumor is true, and the increasingly fragile health of Bella Edwards.

Bella passed away in 1929, after years of illness. Following her partner’s death, Mudocci lived in relative seclusion in England, where she kept few social ties and rarely gave interviews. It’s during these quiet decades that her name began to fade from cultural memory. Despite having been a muse to one of modern art’s most significant figures, and despite her earlier musical acclaim, her death in 1953 passed largely unnoticed by the press or artistic institutions.

She left behind very few personal records. No memoir, no extensive letters, and no public reflection on her life with Munch or Edwards. This silence has allowed more space for speculation, but also added to her mystique. For historians, Mudocci remains difficult to categorize — not quite a socialite, not entirely a recluse, and not easily claimed by any single movement or identity.

It wasn’t until the late 20th and early 21st century that scholars and curators began to reevaluate her importance. As interest in the women behind major male artists grew, Mudocci’s role as a muse — and possibly much more — earned renewed attention. Today, her portrait in The Brooch is often viewed as one of Munch’s most emotionally resonant works, a reminder of a woman whose power lay not in exposure, but in her enduring quiet.

Munch’s Muse Revisited: Art History’s Quiet Reclamation

In recent years, Eva Mudocci has been gradually reclaimed by art historians, curators, and biographers seeking to restore the stories of women who shaped the work of male artists without receiving due credit. While Mudocci was not a painter or sculptor herself, her influence on Munch is now widely acknowledged as both stylistic and personal. Her cool detachment, modern elegance, and resistance to being defined became thematic elements in Munch’s evolving portrayal of women.

Exhibitions at the Munch Museum and retrospectives in Oslo, Berlin, and London have included The Brooch as a central piece. In these contexts, the portrait is often framed not just as a romantic relic, but as a modernist turning point. Unlike the earlier Madonna or The Sick Child — which express deep anguish or erotic chaos — The Brooch introduces a woman who stands alone, untouched by Munch’s usual psychological projections. That shift is now seen by some scholars as the beginning of a more introspective and less overtly symbolic phase in his art.

Recent books and journal articles have also begun to take her seriously as a subject worthy of independent attention. Some explore her as a queer figure navigating a conservative world, while others focus on her aesthetic role in helping Munch craft a new visual language of restraint and ambiguity. Either way, the image of Eva Mudocci has moved from the margins of footnotes to the center of important discussions about gender, influence, and artistic agency.

- Modern reevaluations of Mudocci include:

- Scholarly essays in exhibition catalogues for major Munch retrospectives

- Feature displays of The Brooch in museums across Europe

- Renewed interest in Bella Edwards and their partnership

- Media investigations into the child paternity claim

- Inclusion in books on overlooked women in modernist art circles

Today, Mudocci stands as a reminder that not all muses are passive, nor are they always consumed by the artists they inspire. Her legacy lives in the silence she maintained and the art she helped bring into being — without asking for recognition, but receiving it nonetheless, decades later.

Key Takeaways

- Eva Mudocci was a celebrated English violinist and muse to Edvard Munch.

- Munch’s 1903 lithograph The Brooch immortalized her in modern art.

- Their relationship, though brief, had a lasting artistic impact.

- Mudocci shared her life with Bella Edwards in a long-term lesbian partnership.

- Her legacy was revived in the 21st century through scholarship and museum retrospectives.

FAQs

Who was Eva Mudocci?

Eva Mudocci was an English violinist and the subject of Edvard Munch’s iconic 1903 portrait The Brooch. She toured widely in Europe and was admired for her talent and style.

Did Eva Mudocci and Edvard Munch have a romantic relationship?

Their relationship was emotionally intense and possibly romantic, but the true nature remains unclear. Munch was clearly inspired by her, though she remained distant and self-contained.

What is The Brooch by Edvard Munch?

The Brooch. Eva Mudocci is a 1903 lithograph by Munch, portraying Mudocci in stark contrast and deep shadow. It’s considered one of his most restrained and enigmatic portraits.

Was Eva Mudocci in a lesbian relationship?

Yes, she shared her life and career with pianist Bella Edwards. They lived and traveled together for over two decades and are understood today to have been a couple.

Did Eva Mudocci have a child with Edvard Munch?

A theory emerged in the 2010s suggesting she bore Munch’s child around 1908. DNA evidence has not confirmed this, and the claim remains unproven but persistent.