European Luminism is an artistic movement that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, primarily in Belgium and the Netherlands. It is characterized by its fascination with light, atmosphere, and color, creating compositions that appear almost ethereal. While often linked to Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism, Luminism has its own distinct approach, focusing on the effects of natural illumination rather than the fleeting moments favored by the Impressionists. Unlike American Luminism, which developed earlier and emphasized detailed landscapes with a serene atmosphere, European Luminism leaned toward vibrant hues and a more expressive interpretation of light.

The movement developed in a period of rapid industrialization, scientific discovery, and artistic transformation in Europe. Many Luminist painters were inspired by advancements in color theory and optical science, which revealed new ways to depict the interplay between light and the environment. The influence of Impressionism, particularly the work of Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, played a significant role in shaping Luminist ideals. However, rather than breaking forms down into loose, fleeting strokes, Luminist painters maintained a sense of structure while still capturing the radiance of sunlight on landscapes and cityscapes.

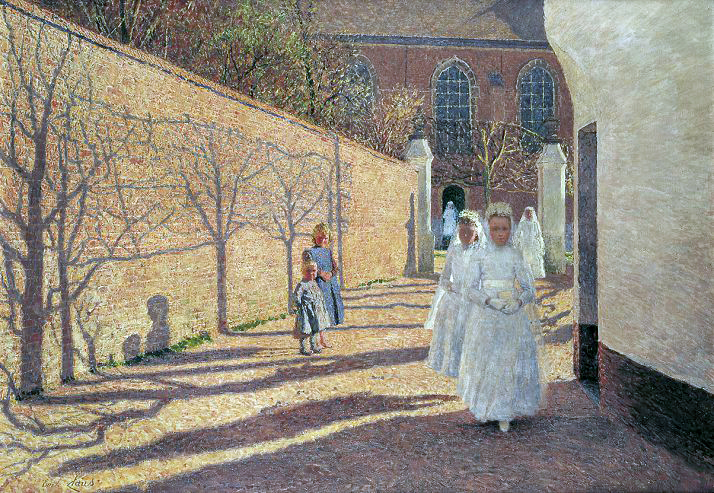

European Luminists often chose tranquil subjects such as countryside scenes, seaside vistas, and sunlit urban settings. Their paintings aimed to convey an emotional experience of nature rather than simply document a visual moment. Artists such as Emile Claus, Théo van Rysselberghe, and Jan Toorop sought to elevate landscape and genre painting by infusing their works with a luminous, dreamlike quality. Their use of soft transitions, vibrant colors, and atmospheric effects set them apart from their contemporaries.

Although European Luminism did not form a centralized, organized school, it was deeply influential in Belgium and the Netherlands. Many of its leading painters were associated with artistic circles such as Les XX (The Twenty) and La Libre Esthétique, which promoted avant-garde movements in Belgium. The movement remained relevant well into the 20th century, influencing later artistic developments in modernism. Today, it is recognized as a vital part of European art history, bridging the gap between Impressionism and the more abstract tendencies of the early modernist era.

The Origins and Historical Context of Luminism

The late 19th century was a time of significant change in Europe, with industrialization, urban expansion, and technological advancements reshaping everyday life. In response to these rapid transformations, many artists turned to nature, seeking to capture its beauty through innovative approaches to color and light. In Belgium and the Netherlands, this artistic shift led to the emergence of Luminism, a movement that emphasized radiant, atmospheric landscapes and a heightened awareness of light’s impact on the natural world. The movement’s rise coincided with the increasing popularity of Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism, which had already revolutionized artistic methods across Europe.

One of the key influences on Luminism was the scientific study of color and light, particularly the work of Michel Eugène Chevreul, a French chemist who explored the way colors interact with one another. His theories on simultaneous contrast and optical blending fascinated artists, leading them to experiment with how light could be depicted on canvas. Additionally, the discoveries of British scientist James Clerk Maxwell on the nature of color perception further encouraged Luminists to push the boundaries of traditional painting techniques. This scientific approach distinguished Luminism from Impressionism, making it a more calculated yet equally vibrant style.

Belgium was a particularly fertile ground for the development of Luminism, as artists there sought to break away from the constraints of academic painting while maintaining a focus on clarity and structure. The Belgian avant-garde movement, led by groups such as Les XX, provided a platform for experimentation, allowing artists to refine their approach to light and color. The Netherlands, with its long history of landscape painting dating back to the Dutch Golden Age, also proved to be an ideal setting for Luminist ideas to flourish. The Dutch preference for atmospheric depictions of nature found a new, modern expression in Luminism.

Despite its innovative approach, Luminism was often overshadowed by the more radical developments of Cubism and Fauvism in the early 20th century. However, it remained a beloved style among artists who sought to preserve the poetic, immersive qualities of nature in their work. The movement gradually faded from the forefront of the European avant-garde but left an indelible mark on future generations of landscape and colorist painters. Its emphasis on luminosity and natural beauty continues to resonate with contemporary audiences and artists alike.

Key Characteristics of Luminist Painting

Luminism is defined by its exceptional focus on the depiction of light, often capturing the glow of the sun at various times of the day. Unlike Impressionism, which sought to depict fleeting moments through quick, broken brushstrokes, Luminism embraced a more controlled, refined application of paint. This allowed for smoother transitions between colors and a more gradual modulation of light and shadow, creating a heightened sense of atmosphere. The resulting effect gives many Luminist paintings an almost otherworldly glow, making them stand out from other landscape works of the time.

One of the most striking features of Luminist paintings is their color palette, which tends to be bright yet harmonious. Many Luminists were deeply influenced by scientific theories on color relationships, particularly the principles of Divisionism pioneered by Georges Seurat. However, unlike Divisionists, who applied distinct dots of pure color, Luminists used softer, more blended transitions to maintain a sense of realism. This meticulous handling of color allowed them to create vivid, sunlit effects without losing the overall clarity of form.

The subject matter of Luminist paintings often revolved around landscapes, rivers, seascapes, and pastoral settings, reflecting a romanticized vision of nature. Some artists also painted urban scenes, though these were typically infused with a sense of tranquility rather than bustling activity. The emphasis on open spaces and vast skies contributed to the dreamlike quality of Luminist works. Many compositions feature reflective surfaces, such as water or dew-covered grass, which enhance the impression of shimmering light.

Despite its similarities to Impressionism, Luminism can be distinguished by its greater emphasis on composition and structure. Impressionist works often have a spontaneous, sketch-like quality, whereas Luminist paintings are carefully arranged and balanced. This reflects the movement’s roots in traditional European landscape painting, particularly the Dutch landscape tradition of the 17th century. However, Luminists introduced a modern sensibility by infusing their works with an almost scientific understanding of light.

Major Luminist Artists and Their Masterpieces

Several artists played a crucial role in shaping European Luminism, particularly in Belgium and the Netherlands. These painters shared a common fascination with light and its effects, but each had a unique approach to capturing luminosity on canvas. Emile Claus (1849–1924) is often considered the most important Belgian Luminist, blending Impressionist influences with his distinctive use of golden sunlight and vibrant color contrasts. His masterpiece, The Beet Harvest (1890), exemplifies his ability to depict rural life bathed in warm, glowing light. Claus’ work is deeply connected to the Flemish countryside, which he painted with an almost poetic reverence.

Another key figure in Luminism was Théo van Rysselberghe (1862–1926), who initially worked within the Neo-Impressionist tradition before embracing Luminism. His paintings often feature seaside scenes, sunlit interiors, and portraits, with an emphasis on optical blending and vibrant color dynamics. Works like The Reading (1903) showcase his precise yet expressive handling of light, particularly in the way he renders sunlight filtering through trees. Van Rysselberghe’s art straddles the boundary between scientific Divisionism and the more fluid Luminist aesthetic, making him a bridge between the two styles.

Albert Baertsoen (1866–1922) brought an urban perspective to Luminism, focusing on industrial landscapes, misty rivers, and cityscapes bathed in atmospheric light. Unlike Claus and van Rysselberghe, who often depicted idyllic rural scenes, Baertsoen captured the quiet beauty of modern European cities, particularly those of Belgium. His muted, reflective works, such as The Ghent Quays in the Morning Mist, convey a sense of serenity while still showcasing his mastery of luminosity and atmosphere. His paintings emphasize the poetic interplay between artificial and natural light, particularly in harbors and riverside views.

Dutch artist Jan Toorop (1858–1928) took Luminism in a more Symbolist direction, blending mystical themes with glowing, radiant color palettes. While he is often associated with Art Nouveau and Symbolism, his later works, such as The Sunlight on the Dunes, demonstrate his fascination with light’s emotional and spiritual qualities. Toorop’s unique style combined elements of Luminism, Neo-Impressionism, and decorative line work, making his contributions to the movement particularly distinctive. His experimental approach helped bridge Luminism with early 20th-century modernist trends.

The Influence of Luminism on Later Art Movements

While Luminism never became a formally organized movement like Impressionism, its influence extended into the 20th century, shaping various modernist approaches to color and light. One of the most direct successors of Luminism was Fauvism, a movement led by artists such as Henri Matisse and André Derain in the early 1900s. The Fauvists took the Luminists’ vibrant use of color and pushed it further, using intensely saturated hues and expressive brushwork to convey emotion. Although the Fauves abandoned the delicate transitions and optical blending seen in Luminist works, they built upon its scientific understanding of color relationships.

Luminism also had a profound impact on Expressionism, particularly in the Low Countries, where artists sought to capture emotional depth through color and atmosphere. Painters such as Gustave De Smet and Constant Permeke, who became key figures in Belgian Expressionism, absorbed Luminist principles before developing their own more abstracted, emotional landscapes. The emphasis on light’s transformative power carried over into their work, even as they moved toward bolder, more exaggerated forms.

Another area where Luminism left its mark was modern photography, particularly in the way photographers learned to manipulate natural light. The delicate interplay between shadows, highlights, and reflections, which Luminists mastered on canvas, found a parallel in early 20th-century pictorialist photography. Photographers like Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz explored similar ideas, treating light as a subject in itself. The Luminist approach to composition—favoring wide horizons, open spaces, and atmospheric effects—became a lasting influence in both painting and photographic art.

Even in contemporary digital art, the Luminist aesthetic remains relevant, as artists use color gradients, lens flares, and ambient lighting to create immersive environments. Video game design and cinematic visuals frequently incorporate Luminist-inspired lighting techniques, proving that the movement’s exploration of light is far from obsolete. Although Luminism as a historical movement may not have achieved the fame of Impressionism or Cubism, its legacy continues to shape visual culture in ways both subtle and profound.

Rediscovery and Revival of Luminism in the 20th and 21st Centuries

For much of the early 20th century, Luminism was overshadowed by avant-garde movements such as Cubism, Futurism, and Surrealism, which dominated the European art scene. However, in the mid-20th century, interest in realist and atmospheric painting began to resurface, leading to a renewed appreciation for Luminist works. Art historians and museum curators began re-evaluating the contributions of Belgian and Dutch Luminists, recognizing their role in bridging Impressionism and early modernist approaches to color. This revival was fueled by exhibitions in major European galleries, which showcased Luminist paintings alongside their better-known Impressionist counterparts.

One of the most significant exhibitions that helped restore Luminism’s reputation was the 1979 retrospective on Emile Claus, held at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. The exhibition brought renewed attention to Claus and his contemporaries, leading to further studies on the movement’s impact. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, scholars published new research on the connections between Luminism, Neo-Impressionism, and Fauvism, solidifying its place in the history of European modern art. Many museums in Belgium and the Netherlands began acquiring and restoring Luminist masterpieces, ensuring their preservation for future generations.

Today, major institutions such as the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam house impressive collections of Luminist works. These paintings are now recognized as vital representations of European landscape and colorist traditions, offering a unique perspective on the evolution of modern art. The renewed focus on Luminism has also encouraged contemporary artists to explore its emphasis on light and atmospheric effects, leading to neo-Luminist interpretations in painting and digital media.

With growing public interest in natural beauty and environmental themes, Luminism’s emphasis on harmony between light and landscape has found new relevance. Many art collectors now seek out Luminist works, recognizing their calming, meditative qualities in contrast to the often chaotic nature of modern visual culture. As appreciation for historical color theories and traditional techniques continues to grow, Luminism remains an important touchstone for artists and art lovers alike.

Why Luminism Still Matters Today

Luminism remains relevant in today’s art world because of its timeless focus on light, atmosphere, and emotional depth. In an era dominated by digital screens and artificial lighting, the movement’s dedication to natural illumination and color harmony offers a refreshing contrast. Many contemporary artists, including painters, photographers, and digital creators, continue to draw inspiration from Luminist techniques. The movement’s ability to evoke a sense of peace, nostalgia, and serenity resonates deeply with modern audiences who seek a connection to nature amid the distractions of modern life.

The rise of environmental consciousness and ecological awareness has also renewed interest in Luminism. As climate change and urbanization threaten many of the landscapes that inspired Luminist painters, their works serve as a reminder of nature’s fragile beauty. The movement’s emphasis on rural and coastal settings bathed in soft light aligns with contemporary concerns about preserving natural environments. Many modern landscape painters and conservation photographers use similar techniques to highlight the beauty of threatened ecosystems, making Luminism more relevant than ever.

Another reason Luminism continues to captivate art enthusiasts is its unique blend of realism and emotion. Unlike purely abstract art, Luminist paintings maintain a strong sense of place and form, making them accessible to viewers who may not be drawn to more experimental styles. At the same time, their use of light and color creates an almost dreamlike quality, allowing for emotional engagement beyond simple representation. This balance between scientific precision and poetic atmosphere ensures that Luminist works remain powerful and evocative.

For collectors and museum visitors, Luminist paintings offer a gateway into a lesser-known but profoundly beautiful movement. With major exhibitions and museum acquisitions bringing renewed attention to Luminist masters, more people are discovering the movement’s significance. Whether viewed in a gallery, studied in an art history class, or referenced in contemporary visual media, Luminism continues to inspire both artists and audiences alike. Its legacy, rooted in the power of light and color, ensures that it will never fade from the artistic landscape.

Key Takeaways

- Luminism emerged in Belgium and the Netherlands in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, influenced by Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism.

- Artists like Emile Claus, Théo van Rysselberghe, and Jan Toorop developed unique approaches to depicting light, atmosphere, and color.

- Scientific color theory and optical blending techniques played a significant role in shaping Luminist aesthetics.

- The movement influenced later styles, including Fauvism, Expressionism, and modern photography.

- Luminism remains relevant today, inspiring artists and reflecting contemporary concerns about nature and environmental preservation.

FAQs

What is the main difference between Luminism and Impressionism?

Luminism focuses on soft, blended light effects and structured compositions, while Impressionism emphasizes fleeting moments, rapid brushstrokes, and spontaneous color application.

Which countries were most associated with European Luminism?

Luminism was particularly prominent in Belgium and the Netherlands, where artists experimented with light and color in landscape and urban scenes.

How did scientific discoveries influence Luminism?

The work of scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul and James Clerk Maxwell influenced Luminists, leading them to explore optical blending, color contrast, and light perception in their paintings.

Why did Luminism fade in popularity in the early 20th century?

Luminism was overshadowed by Cubism, Futurism, and Surrealism, which embraced abstraction and experimental forms, moving away from the naturalistic light effects that defined Luminism.

Where can I see Luminist paintings today?

Luminist works can be found in major museums such as the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, as well as private collections.