Dresden is a city suspended between grandeur and tragedy, opulence and resilience. Nestled along the banks of the Elbe River in eastern Germany, Dresden has often been referred to as the “Florence on the Elbe”—a nickname that hints not only at its aesthetic splendor but also at its centuries-old stature as a European cultural capital. It is a city where art has not only adorned the walls of palaces and museums, but has also been interwoven into the identity of its people, their institutions, and even their traumas.

The story of Dresden’s art history is layered like a palimpsest—each era writing over the last, yet never entirely erasing it. From its days as the glittering seat of the Electors of Saxony, to its central role in Baroque architecture and the flourishing of Romantic painting, Dresden has long served as a canvas for artistic ambition. The city’s trajectory has been shaped by kings and collectors, architects and avant-gardists, all of whom left indelible marks that persist through the ravages of war and the shifting tides of political ideology.

In the 18th century, Dresden rivaled the courts of Paris and Vienna, its royal collections swelling with old master paintings, porcelain, and classical antiquities. The foundation of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, home to Raphael’s Sistine Madonna, became a declaration of artistic prestige. Yet Dresden was never merely a museum city; it also produced some of Germany’s most innovative painters and thinkers. Caspar David Friedrich, with his introspective landscapes, helped pioneer Romanticism, while in the early 20th century, the bold Expressionists of the Die Brücke group brought raw emotion and social critique into the heart of modernism.

But Dresden’s artistic legacy is not only one of creation—it is also a story of destruction. In February 1945, a firestorm unleashed by Allied bombing razed much of the historic city, reducing baroque landmarks to rubble and imperiling priceless cultural treasures. The images of a smoldering Dresden became icons of wartime devastation, their symbolism far outlasting the war itself. In the years that followed, during the GDR era and beyond, Dresden became a test case for cultural recovery, its institutions tasked with not only restoring stone and pigment, but also reclaiming a sense of artistic identity.

Today, Dresden stands as both a resurrected wonder and a living city of art. Its skyline—dominated once again by the Frauenkirche, painstakingly rebuilt from wartime ash—tells a story of renewal. The museums of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden house one of the world’s most impressive ensembles of art, from Renaissance paintings to contemporary installations. Galleries and artist-run spaces continue to emerge in the city’s Neustadt district, and cultural festivals draw global audiences. Dresden is no longer merely a symbol of the past, but an active participant in the art world’s evolving conversation.

This deep-dive will trace the arc of Dresden’s art history across centuries, exploring the figures, institutions, and events that have defined its creative legacy. From porcelain to painting, Romanticism to Expressionism, we will navigate the city’s role in shaping—and surviving—the turbulent history of art in Europe.

The Rise of the Saxon Court: Patronage and Prestige

To understand the grandeur of Dresden’s artistic legacy, one must begin with the rise of the Saxon Electors—a line of rulers whose ambitions turned a relatively modest medieval town into one of the most refined cultural centers in Europe. Their vision, wealth, and strategic patronage laid the foundations for the city’s golden age, transforming Dresden into a magnet for artists, architects, and intellectuals from across the continent.

The pivotal moment came in the late 15th century, when the Wettin dynasty consolidated its rule over Saxony. But it was in the 16th century that Dresden began to assert itself as a court of consequence. The Elector Maurice of Saxony (1521–1553) moved the ducal residence from the fortress town of Meissen to Dresden, establishing it as the political heart of Saxony. While still far from a cultural powerhouse, this shift marked the beginning of Dresden’s transformation.

It was under Augustus the Strong (1670–1733), Elector of Saxony and later King of Poland, that Dresden ascended to artistic prominence. A towering figure in both stature and ambition, Augustus had a taste for splendor that bordered on the obsessive. His passion for the arts was not merely decorative—it was ideological. Art, in his court, was a projection of power, a tool of diplomacy, and a declaration of Saxony’s rightful place among Europe’s great powers.

Augustus and his court cultivated a dazzling array of artistic endeavors. They invested in architecture, commissioning palaces and civic buildings in the lavish Baroque style that would become Dresden’s signature. The expansion of the royal palace, the construction of the Taschenbergpalais, and the early designs of the Zwinger were all initiated during his reign. More than mere monuments, these buildings were immersive environments for courtly life, encrusted with sculpture, frescoes, and gilded ornamentation.

Beyond architecture, Augustus was a voracious collector. He amassed a staggering array of treasures—paintings, coins, armor, scientific instruments, and most famously, porcelain. The creation of the Green Vault (Grünes Gewölbe), a treasure chamber unlike any other in Europe, showcased the Elector’s taste for the extravagant and the rare. Lavishly displayed in specially designed rooms, the Green Vault’s contents blended Renaissance and Baroque artistry with princely spectacle, turning art collecting into a performative act of sovereignty.

One of the most transformative acts of Augustus’s reign was his patronage of Johann Friedrich Böttger, the alchemist-turned-ceramist whose experiments led to the invention of Europe’s first true hard-paste porcelain. In 1710, the Meissen Porcelain Manufactory was founded under royal protection, and soon Dresden was the epicenter of a porcelain revolution. The white gold of Meissen not only flooded European courts with exquisitely crafted figurines and tableware but also became a symbol of Saxon ingenuity and artistic leadership.

Augustus’s court attracted artists and craftsmen from across Europe, drawn by the promise of commissions and prestige. Venetian painters, Flemish tapestry weavers, French architects, and German sculptors all converged in Dresden, creating a cosmopolitan visual culture steeped in theatricality and precision. Court painters like Louis de Silvestre helped create a visual language that fused French elegance with German grandeur, while engravers and printmakers disseminated images of Dresden’s opulence throughout Europe.

The legacy of Augustus the Strong extended well beyond his lifetime. His son, Augustus III, inherited not only the throne but also his father’s passion for collecting. It was under Augustus III that the famed Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister began to take form. The acquisition of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna in 1754 marked a high point, affirming Dresden’s status as a center of connoisseurship and taste.

Yet the court’s patronage wasn’t solely about flaunting wealth—it had profound institutional consequences. The royal collections formed the nucleus of Dresden’s future museums, and the aesthetic values cultivated under the Wettins would shape generations of German artists. By the mid-18th century, Dresden was no longer just a residence for princes—it was an image of princely power rendered in stone, paint, and porcelain.

The Saxon court’s cultural investments were both a product and a projection of their political ambitions. As Protestant rulers with Catholic aspirations, as regional leaders with imperial pretensions, the Wettins used art to craft a visual rhetoric of legitimacy, transcendence, and belonging. And in doing so, they gave Dresden an identity that would endure long after their dynastic power waned.

Baroque Brilliance: Architecture and Ornament in the 17th–18th Centuries

If the Saxon court provided the political will and financial muscle for Dresden’s artistic rise, it was the Baroque era that gave the city its unforgettable visual identity. Nowhere in Germany—and perhaps nowhere in northern Europe—was the language of Baroque architecture spoken with such fluency and flamboyance as it was in Dresden during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The city became a stage set for absolutist spectacle, its buildings choreographed to dazzle, impress, and proclaim power through aesthetic excess.

At the center of this architectural transformation stood Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann, a self-taught genius whose vision would define Dresden’s skyline. Born in 1662 in Herford, Pöppelmann rose through the ranks from humble beginnings, eventually becoming court architect under Augustus the Strong. His work fused the dynamism of Italian Baroque with the rigor of French Classicism and a distinct Saxon theatricality. His crowning achievement—and the crown jewel of Dresden’s Baroque heritage—is the Zwinger.

Constructed between 1710 and 1728, the Zwinger was initially conceived as an orangery and a venue for court festivities, but it evolved into a complex that combined pleasure, prestige, and encyclopedic ambition. With its sweeping arcades, sculpted balustrades, and exuberant ornamentation by sculptor Balthasar Permoser, the Zwinger was both garden and gallery—a place where architecture, sculpture, and courtly ceremony merged into a single aesthetic experience. It embodied what the Baroque did best: turn art into a form of lived theater.

Permoser’s role cannot be overstated. His work for the Zwinger, particularly the dramatic Nymphenbad and the ornate crowning figures above the portals, infused the site with expressive power. His sculptures of mythological figures writhe with energy and sensuality, capturing the Baroque fascination with movement and emotional intensity. Permoser was also responsible for the opulent pulpit in the Hofkirche and contributed to numerous tomb monuments and allegorical works throughout the city.

Outside the Zwinger, the Baroque made its mark in nearly every corner of Dresden. The Catholic Court Church (Hofkirche), built in the 1730s by Italian architect Gaetano Chiaveri, introduced Roman ecclesiastical grandeur to Protestant Saxony—a paradox that reflected the political complexities of Augustus the Strong’s conversion to Catholicism to become King of Poland. Its towering silhouette and richly sculpted balustrades form a key part of Dresden’s riverfront panorama, a composition that rivals the Thames at Westminster or the Seine at Paris.

Equally significant is the Japanisches Palais, originally designed as a repository for Augustus’s expanding porcelain collection. Though the king’s porcelain dreams outgrew even this capacious building, the Palais remains a testament to the cosmopolitan curiosity of the age—a European building with Asian aspirations, embodying the fascination with exoticism that permeated Baroque collecting and display.

Baroque Dresden wasn’t just monumental—it was immersive. Urban planning played a key role in choreographing movement and sightlines. The processional route from the royal palace to the Zwinger, from the Hofkirche to the Augustus Bridge, was carefully composed to guide the eye and glorify the ruler. Streets, squares, and façades became part of a grand scenography. This performative urbanism, inherited from the absolutist courts of Italy and France, found a uniquely German articulation in Dresden, blending ornamental density with spatial drama.

Inside these buildings, the interiors continued the spectacle. Gilded stucco ceilings, painted allegories, marble columns, and richly inlaid floors transformed every surface into a bearer of symbolic meaning. The use of trompe l’œil—illusionistic painting techniques that extended architecture through paint—added layers of theatricality and wonder. Even furnishings and textiles were part of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art that Baroque Dresden aspired to become.

Despite its seeming opulence, Dresden’s Baroque art was not frivolous. It was deeply political. The scale, symbolism, and iconography of its buildings were calibrated to convey messages of divine favor, dynastic legitimacy, and cultural supremacy. Augustus the Strong used the Baroque to write Saxony into the narrative of European greatness, countering the dominance of French and Habsburg models with a distinctly German magnificence.

By the mid-18th century, Dresden stood as a peer to Vienna, Paris, and Rome in architectural prestige. Foreign visitors were astounded by its skyline, its collections, and the integrated beauty of its urban core. The court’s commitment to beauty had become institutionalized, with academies and workshops dedicated to sustaining and disseminating the Baroque style.

Yet this golden age was not to last forever. By the 1760s, tastes began to shift. The Enlightenment ushered in a new aesthetic sensibility—one that favored clarity, reason, and classical restraint over Baroque drama. Neoclassicism would eventually replace the florid stylings of the Baroque, but its monuments remained. And in Dresden, they remained not as relics, but as vital, living parts of the city’s visual identity.

The brilliance of Baroque Dresden survives not just in stone and stucco, but in the city’s self-image—a place where art and life are inseparable, where public space becomes a stage, and where architecture remembers its royal past even in modern times.

The Zwinger and the Dresden Porcelain Legacy

Among Dresden’s many artistic treasures, the Zwinger stands out not only for its architectural splendor but for its role as a vessel of cultural innovation and imperial aspiration. It is a building where beauty meets obsession—a locus of artistic achievement that encapsulates Dresden’s unique fusion of Enlightenment science, Baroque spectacle, and the glittering ambitions of the Saxon court. And entwined with the Zwinger’s story is the rise of Meissen porcelain, a technological and artistic marvel that forever altered the trajectory of European decorative arts.

The Zwinger, conceived under the patronage of Augustus the Strong, was never intended as a palace in the traditional sense. Rather, it was a festival ground, a place for courtly rituals, tournaments, and exhibitions—a kind of architectural theater designed to astonish. Its very name, “Zwinger,” refers to the space between the outer and inner defensive walls of a fortress, though by the 18th century, its martial origins had given way to theatrical grandeur. Designed by court architect Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann and adorned by sculptor Balthasar Permoser, the Zwinger’s curving galleries, elaborate gates, and sculpted fountains create a rhythm of movement and delight.

Yet the Zwinger was more than stagecraft. It was also a repository of knowledge and aesthetic refinement. As part of Augustus the Strong’s vision to make Dresden a cultural beacon, the Zwinger housed several of the royal scientific and artistic collections. Among them was the collection of mathematical and physical instruments (now the Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon), which reflected the Enlightenment’s fascination with measurement and mechanics, and—perhaps most famously—Augustus’s unparalleled collection of porcelain.

The king’s obsession with porcelain bordered on the fanatical. Known as “white gold” due to its rarity and value, porcelain had been imported from China for centuries and was a prized luxury among European elites. But in the early 18th century, Augustus took the unprecedented step of trying to produce it at home. He imprisoned the young alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger in Dresden, originally in hopes of discovering the secret of transmuting base metals into gold. Instead, Böttger—working alongside chemist Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus—discovered something arguably more valuable: the formula for hard-paste porcelain.

In 1710, the Meissen Porcelain Manufactory was founded just outside Dresden. It was Europe’s first successful producer of true porcelain, breaking China’s centuries-long monopoly. The royal workshop soon attracted artists, modelers, and painters who developed a visual vocabulary uniquely suited to the medium: delicate glazes, rich floral motifs, exotic chinoiserie scenes, and finely sculpted figurines of mythological and pastoral subjects.

Meissen porcelain was both technological triumph and aesthetic revolution. The ability to mold and fire such intricate objects enabled a new kind of decorative art—one that combined painterly finesse with sculptural detail. The manufactory’s pieces graced banquet tables, altars, and cabinets throughout Europe, and the Meissen mark (crossed swords) became a symbol of Saxon prestige.

In the Zwinger, porcelain took pride of place. Augustus the Strong amassed over 20,000 pieces—an extraordinary collection that rivaled any in the world. His desire to display this collection in an appropriately magnificent setting led to early plans to convert the Japanisches Palais into a porcelain palace, though that project remained unfinished. Still, the ambition was clear: porcelain was not just a craft—it was a marker of Enlightenment refinement and monarchical supremacy.

The Zwinger and Meissen porcelain were part of the same grand narrative: an attempt to position Dresden as a capital of culture and sophistication, capable of matching and even surpassing the courts of Paris, Vienna, and Versailles. The building’s ornate sculptural program, filled with allegories of science, art, and nature, reflected the encyclopedic worldview of the age. Like a Baroque encyclopedia made real, the Zwinger embodied the idea that knowledge and beauty could coexist in perfect harmony.

After Augustus’s death, the production of Meissen porcelain continued to flourish under state sponsorship, evolving stylistically to meet the changing tastes of the Rococo and Neoclassical periods. The manufactory’s technical achievements and visual inventiveness influenced countless imitators, from Sèvres in France to Chelsea in England, but the Meissen factory retained its symbolic role as the cradle of European porcelain.

Today, the Zwinger remains at the heart of Dresden’s cultural life. Its reconstructed galleries now house several of the city’s major art collections, including the Porzellansammlung (Porcelain Collection), the Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon, and the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Visitors can still see Meissen masterpieces on display—gilt teapots, ornate vases, and whimsical figurines that once adorned the tables of kings. In this sense, the Zwinger continues to function as it was intended: a place where power, pleasure, and knowledge converge.

The legacy of Dresden’s porcelain is also alive in contemporary ceramic practice. Artists and collectors around the world still look to Meissen for its technical mastery and historical prestige. And in a city so marked by destruction and restoration, porcelain’s paradoxical nature—fragile yet enduring—seems a perfect metaphor for Dresden itself.

The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister: A European Treasure

In the heart of Dresden, nestled within the Zwinger complex, lies one of the most revered painting collections in Europe: the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Picture Gallery). This museum is more than a repository of fine art—it is a monument to the centuries-old tradition of collecting, connoisseurship, and cultural diplomacy. With over 700 works spanning the 15th to the 18th centuries, it encapsulates Dresden’s historical aspiration to sit among Europe’s great centers of culture, alongside the Louvre in Paris and the Uffizi in Florence.

The origins of the Gemäldegalerie trace back to the 18th century, under the reign of Augustus III, the son of Augustus the Strong. Whereas his father had focused on architecture and the decorative arts, Augustus III was drawn to painting. An enthusiastic collector with a sharp eye and deep pockets, he sought to build a world-class collection of European masterpieces, focusing on Italian Renaissance, Flemish, Dutch, and German works. He wasn’t just acquiring paintings; he was assembling a canon—a visual library of human achievement.

The king’s acquisitions were facilitated by trusted agents and advisors, chief among them the erudite court painter Franz Lépicié and the Saxon ambassador in Venice, Franz Joseph von Hoffmann. These intermediaries scoured the continent, purchasing entire private collections and negotiating with monastic institutions and cash-strapped nobility. One of the most significant moments came in 1745, when Augustus III purchased around 100 paintings from the prestigious Duke of Modena’s collection—an acquisition that instantly elevated Dresden’s status in the art world.

Among the gallery’s crown jewels is Raphael’s “Sistine Madonna”, acquired in 1754 for the then-staggering sum of 25,000 thalers. This painting alone would make any museum proud: the ethereal Virgin and Child flanked by St. Sixtus and St. Barbara, and anchored below by the famously wistful cherubs. The painting’s arrival in Dresden caused a sensation, and over time it became an icon not only of the museum but of German Romanticism, inspiring poets, philosophers, and fellow painters. Heinrich Heine and Goethe wrote about it; Caspar David Friedrich drew spiritual sustenance from it.

The gallery soon amassed a formidable collection of Flemish Baroque masterpieces, particularly the work of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Jacob Jordaens, all admired for their dynamic compositions and sumptuous textures. From the Dutch Golden Age came the meticulous still lifes of Jan Davidsz de Heem, the genre scenes of Jan Steen, and luminous landscapes by Jacob van Ruisdael. The Italian holdings included Titian, Veronese, Correggio, and Guido Reni—artists whose works brought sensuality, drama, and idealized beauty to the Saxon court.

But the Gemäldegalerie also had a distinct German voice. Lucas Cranach the Elder, court painter to the Electors of Saxony and friend to Martin Luther, is represented by numerous works that reveal the moral and religious tensions of the Reformation. His figures, often elongated and enigmatic, convey a world of theological debate and princely power. The gallery’s inclusion of such works reflected not only artistic taste but also a regional pride in Saxony’s role in shaping European religious and cultural history.

As the collection grew, the need for a suitable exhibition space became pressing. Initially housed in various palace rooms, the paintings were moved into the Zwinger in the mid-19th century, after a new gallery wing was built to properly showcase the artworks. The resulting museum was one of the first in Europe to embody the modern principles of display: natural light, chronological arrangement, and educational accessibility. The curators aimed not only to impress but to instruct, reflecting Enlightenment ideals of public learning and civic pride.

Throughout the 19th century, the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister was a point of pilgrimage for artists, scholars, and tourists. Dresden became synonymous with refined artistic taste, a city where one could commune with the Old Masters in relative quiet, away from the crowds of Paris or Rome. Even during the tumultuous decades of the early 20th century, the gallery maintained its stature as a bastion of classicism and connoisseurship.

But the 20th century brought immense challenges. During the Nazi regime, Dresden’s museums were caught in the ideological crosshairs. While modernist works were labeled “degenerate” and removed, the Old Masters were exalted as symbols of Aryan heritage. Then, in February 1945, disaster struck. The Allied bombing of Dresden caused catastrophic damage to the city. Miraculously, many of the Gemäldegalerie’s treasures had been evacuated to secure locations in the countryside—but the building itself suffered damage, and several works were lost or looted.

In the postwar years, Dresden fell within the Soviet-occupied zone, and the paintings that had been hidden were taken to Moscow as “war trophies.” For ten years, they remained in the USSR, until a thaw in diplomatic relations led to their return in 1955. Their repatriation was hailed as a cultural triumph, though the museum continued to operate under the ideological constraints of East German socialism. During the GDR era, the gallery remained a symbol of cultural continuity, quietly resisting the utilitarian aesthetic of the socialist state.

Since reunification, the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister has undergone major renovations and curatorial reevaluations. Today, the museum is presented not as a shrine to European aristocracy but as a living dialogue between past and present. New interpretive materials, multilingual labels, and thematic exhibitions engage contemporary audiences while preserving the solemnity of the original collection. Visitors encounter the Old Masters not as distant icons but as deeply human observers—painters of joy, grief, beauty, and belief.

The gallery now stands not only as a treasure of Dresden, but of the world—a monument to the enduring power of art to cross borders, bridge centuries, and weather the fires of history. In its hushed halls, beneath the gaze of Madonnas, martyrs, and mythic gods, one can still sense the lofty aspirations of the Electors who built it, and the countless hands that preserved it.

Romanticism and the Dresden School of Painting

As the Enlightenment gave way to revolution and reaction in Europe, a new emotional current surged through the arts. It rejected rationalism in favor of introspection, individual experience, and a profound communion with nature and the sublime. In this moment of cultural upheaval, Dresden emerged as a crucible of Romanticism—a city where landscape painting, philosophical inquiry, and spiritual yearning converged into a movement that would reshape not only German art, but European sensibilities at large.

At the heart of this transformation stood Caspar David Friedrich, one of Romanticism’s most enigmatic and influential figures. Although born in Greifswald in 1774, Friedrich spent most of his mature career in Dresden, which became both his artistic home and emotional refuge. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts Dresden, where the teachings of Neoclassicism still held sway, but it was his reaction against these principles that marked him as a revolutionary.

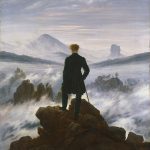

Friedrich’s landscapes are not mere representations of the natural world—they are meditations on time, solitude, mortality, and the divine. In paintings like Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), Monk by the Sea (1808–10), and Chalk Cliffs on Rügen (1818), human figures are often dwarfed by vast, mysterious environments. These are not topographical studies but internal states rendered in mountains, mist, and decaying abbeys. For Friedrich, nature was not a subject—it was a vessel for metaphysical truth.

Dresden in the early 19th century was fertile ground for such a vision. It had weathered the Napoleonic Wars, seen political and social instability, and yet maintained a strong cultural identity. The city’s academy fostered a generation of artists who, while influenced by Friedrich, developed their own voices within what became known as the Dresden School of Painting. This loosely associated group shared an interest in Romantic themes, meticulous technique, and the spiritual resonance of nature.

Among Friedrich’s contemporaries and followers were painters like Carl Gustav Carus, a physician and polymath who combined medical science with poetic landscape painting. His works often echo Friedrich’s in their contemplative tone but introduce a more empirical sensitivity. Carus, who corresponded with Goethe and painted extensively in Saxony and the Alps, viewed nature as a harmonious system—an idea that aligned with the burgeoning field of natural philosophy.

Adrian Ludwig Richter, another major figure of the Dresden School, brought a more narrative and folkloric approach to Romanticism. His works, such as On the Elbe near Dresden or his richly illustrated travel journals, reflect a deep affection for the Saxon countryside and its inhabitants. Richter’s images are less brooding than Friedrich’s, often filled with gentle light, human warmth, and patriotic sentiment. In the post-Napoleonic period, such pastoral idealism offered solace and cultural cohesion.

Philosophy, too, played a crucial role in shaping Romantic art in Dresden. The proximity of Friedrich and his circle to thinkers like Friedrich Schlegel, Novalis, and Johann Gottlieb Fichte created an atmosphere where painting was not only visual but intellectual. The Romantic fascination with the unendliche (the infinite), the ruins of history, and the longing for transcendence found expression across disciplines. Dresden was not just a city of painters—it was a city of ideas.

This cultural ferment extended to music as well. Carl Maria von Weber, composer of the opera Der Freischütz (1821), was based in Dresden and shared the Romantics’ fascination with folklore and the supernatural. The city became a site of Gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork, long before Wagner codified the concept—where music, painting, and poetry worked in concert to evoke a new, emotional world.

The Romantic period in Dresden wasn’t without tensions. Friedrich himself became marginalized later in life, his work seen as too melancholic or out of step with rising Realist trends. The 1848 revolutions brought political upheaval, and with them a new appetite for art that engaged more directly with contemporary life. Yet the spirit of Romanticism lingered in Dresden’s identity, embedded in the city’s landscapes, its museums, and its philosophical traditions.

Friedrich died in relative obscurity in 1840, but his influence only grew with time. The Symbolists and early Expressionists would later look to him as a forerunner, and in the 20th century, German nationalists and modernists alike would claim his imagery for their own purposes—sometimes in contradictory ways. During the Nazi era, his spiritual nationalism was co-opted for ideological ends, while in postwar East Germany, he was reinterpreted as a proto-socialist painter of the German soul.

Today, the Albertinum in Dresden holds many of Friedrich’s surviving works, and he has been restored to his rightful place in the pantheon of Romantic art. His paintings, like the city that nurtured them, have survived wars, reinterpretations, and neglect. They continue to speak to modern viewers with their haunting beauty and existential depth.

The Dresden School, broadly defined, was never a rigid movement. It was a constellation of artists, ideas, and influences that coalesced around a shared sensibility—a belief that art should not only represent the world, but probe its mysteries. In this way, Romanticism in Dresden was not an escape from reality, but an attempt to penetrate its deepest truths.

Music, Opera, and Gesamtkunstwerk: Artistic Fusion in the 19th Century

By the mid-19th century, Dresden had already secured its place in the visual arts through the splendor of its Baroque architecture and the intensity of its Romantic landscapes. But it was in music and theater that Dresden achieved a new kind of artistic fusion—one where performance, sound, staging, and visual spectacle coalesced into a singular cultural force. This idea, famously coined as Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” would find some of its earliest and most influential expressions on Dresden’s stages and in its orchestral halls.

At the center of this movement stood Richard Wagner, whose artistic and political tumult left an indelible mark on Dresden. Appointed Kapellmeister of the Saxon Court in 1843 at just 30 years old, Wagner arrived in a city already rich with musical heritage. Dresden was home to the Staatskapelle Dresden, one of the oldest orchestras in the world, founded in 1548. Its players were esteemed across Europe, and the court’s dedication to music stretched back through centuries of royal patronage. In this fertile environment, Wagner began to develop both his musical innovations and his vision of a totalizing art that would unite drama, poetry, music, and design.

Wagner’s years in Dresden (1843–1849) were creatively fecund. He composed and premiered “Rienzi”, “The Flying Dutchman”, and “Tannhäuser” here—operas that began his long journey toward the mythic grandeur of The Ring Cycle. These works experimented with leitmotifs, mythic narrative, and a dramatic sensibility that drew on Romantic traditions while pushing toward something entirely new. He was not content with music alone; Wagner supervised set designs, costumes, and staging, believing that opera should be an immersive aesthetic experience—an all-encompassing emotional and intellectual world.

His conception of Gesamtkunstwerk was in part a response to the fragmentation of the arts in industrial society. He wanted to recapture a unity of expression he saw in ancient Greek drama and in medieval pageantry. Dresden’s theaters, particularly the Semperoper, became laboratories for these ideas. Though the original Semperoper (designed by Gottfried Semper in 1841) was destroyed by fire in 1869 and later by WWII bombing, its reputation as a stage of innovation and excellence was firmly established in Wagner’s time.

Semper himself was a pivotal figure in this fusion of arts. An architect, theorist, and close friend of Wagner, Semper’s designs combined classical principles with modern theatrical requirements. His interest in polychromy, spatial dynamics, and public engagement paralleled Wagner’s own concerns about the relationship between art and audience. Together, these two men redefined the aesthetic potential of the opera house—not just as a venue, but as a ceremonial space for civic and cultural expression.

The idea of a total work of art didn’t belong to Wagner alone. Dresden’s cultural climate nurtured interdisciplinary ambition. The city was home to visual artists like Ludwig Richter and Carl Gustav Carus, whose work was steeped in literary and musical references. Philosophers and writers gathered in salons and cafés, discussing Schlegel, Goethe, and Novalis alongside Mozart and Beethoven. Artistic boundaries were porous, and the city thrived on this dialogue between forms.

Dresden’s operatic tradition also extended far beyond Wagner. Carl Maria von Weber, who preceded Wagner as Dresden’s Kapellmeister, was instrumental in shaping German Romantic opera. His Der Freischütz (1821) was a seminal work that combined folklore, supernatural elements, and nationalism. Its success laid the groundwork for Wagner’s later innovations and established Dresden as a cradle of the German musical imagination.

Choral music and sacred works also flourished in this period. The Kreuzchor, Dresden’s famed boys’ choir with roots in the 13th century, remained a pillar of the city’s musical identity, performing works from the Renaissance to contemporary compositions. The performance of Bach, once overlooked in many parts of Europe, was revived with new vigor in Dresden’s churches and concert halls, contributing to the broader Romantic rediscovery of the Baroque past.

The notion of artistic fusion was not limited to elite institutions. Civic culture in 19th-century Dresden supported amateur music societies, public lectures, and art education. The Kunstakademie, Dresden’s art academy, integrated studies in drawing, architecture, and art theory, aligning with the broader Romantic vision of unity and synthesis. The city became a model of cultural infrastructure—where different artistic disciplines reinforced and elevated one another.

Politically, this artistic ferment often accompanied revolutionary fervor. Wagner himself was swept up in the 1849 May Uprising in Dresden, a failed attempt to establish a constitutional democracy. Alongside Semper and other radical intellectuals, he fled into exile when the rebellion was crushed. His departure marked the end of an era, but the seeds of his aesthetic and political vision had been sown deeply into Dresden’s cultural fabric.

In the decades that followed, Dresden’s role as a center for Gesamtkunstwerk only expanded. The rebuilding of the Semperoper, completed in 1878, further cemented its reputation. New generations of artists, composers, and designers looked to the Wagner-Semper legacy as a model for interdisciplinary creativity. The city’s opera, orchestra, and theaters remained among the most prestigious in Europe.

By the early 20th century, this heritage would take new forms in modernist experimentation and expressionist theater, but the core idea—of unifying the arts into a transformative experience—remained a defining feature of Dresden’s cultural identity.

Even today, the Semperoper stands as a living monument to this legacy. It is not just a place for performance, but a site of memory and imagination. In its elegant curves and gilded balconies, in the echo of arias and the hush before the overture, one hears the ambition of a city that once sought to dissolve the boundaries between art forms—and, in doing so, to elevate the human spirit.

Modernism in the Shadow of Empire: Expressionism and Die Brücke

At the turn of the 20th century, Dresden stood on the edge of a cultural transformation. The once-princely city, steeped in Baroque splendor and Romantic nostalgia, was about to give rise to one of the most radical movements in European modern art. As the old imperial world staggered toward collapse, a new generation of artists emerged in Dresden, seeking not to refine tradition but to rupture it. These artists would become the vanguard of German Expressionism, and at their heart stood the rebellious collective known as Die Brücke—“The Bridge.”

Founded in Dresden in 1905 by four architecture students—Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff—Die Brücke was more than a stylistic alliance. It was a manifesto. Inspired by Nietzschean philosophy and the raw primitivism of Edvard Munch and Van Gogh, the group sought to bridge the old and the new, the inner and the outer, the individual and society. They rejected academic conventions and bourgeois aesthetics, embracing instead bold color, jagged line, and emotional intensity.

Dresden may seem an unlikely cradle for such revolution. By the early 1900s, it was a well-mannered city of courtly legacy and stately museums, not a seething artistic avant-garde like Berlin or Munich. But precisely because of its cultural conservatism, Dresden proved fertile ground for dissent. The city’s art academy—still steeped in the 19th-century values of realism and historicism—offered little room for experimentation, pushing ambitious students like Kirchner to seek alternative paths.

Die Brücke’s early exhibitions were raw and provocative, often held in makeshift galleries or private apartments. They painted the city’s workers, circus performers, bathers, and street scenes with brash, unblended pigments and distorted forms. Their canvases were not meant to please the eye, but to awaken the soul. As Kirchner wrote in a group manifesto: “We want to express the spiritual in art. We are free.”

Woodcuts became a signature medium. In their rough, graphic clarity, the Brücke artists found an echo of both medieval German art and non-Western traditions, which they admired (problematically, at times) for their supposed authenticity and immediacy. Their use of African masks, Oceanic sculpture, and Japanese prints reflected both an interest in the primal and a critique of European materialism.

Though they often painted from life, the Brücke artists were not Impressionists. They weren’t capturing fleeting light; they were exposing psychic realities. Their works pulsed with anxiety, eroticism, and alienation—feelings that mirrored the tensions of a modernizing empire. Dresden at this time was grappling with rapid industrialization, growing urban poverty, and a rigid imperial bureaucracy. The Brücke artists responded with works that were both celebratory and despairing: erotic nudes alongside haunted cityscapes, joyous dance scenes beside portraits of spiritual dislocation.

Their shared studio in Dresden became a kind of bohemian sanctuary. Nude modeling sessions, communal life drawing, and raucous discussions about art, philosophy, and politics blurred the lines between creation and lifestyle. This merging of life and art was a radical act in itself, anticipating the performance and conceptual movements of the 20th century.

Yet their rebellion was not without costs. Dresden’s cultural establishment remained skeptical, if not hostile. Critics derided their work as crude or degenerate. Public institutions were slow to collect their art. Even within the group, tensions arose. By 1911, Die Brücke had largely relocated to Berlin, drawn by its larger art scene and greater opportunities for recognition. In 1913, the group formally disbanded, though its members continued to shape the course of modernism individually.

The influence of Die Brücke, however, far outlived its brief lifespan. Their work helped define German Expressionism, a movement that would extend through visual art, theater, film, and literature. In the years following World War I, the emotional rawness and social critique pioneered in Dresden would resonate throughout a fractured Germany.

In the 1930s, their legacy came under siege. The Nazi regime labeled modernist art as “Entartete Kunst”—“degenerate art”—and purged Expressionist works from museums. Kirchner, driven to despair by persecution and exile, committed suicide in 1938. Many Brücke works were confiscated, sold abroad, or destroyed. It would take decades for the movement to be reappraised.

After the war, Dresden found itself in the German Democratic Republic, where state-supported realism became the official style. But underground interest in Expressionism persisted. In a bitter irony, the very movement once shunned by the court and later banned by fascism was quietly studied and admired by artists working under socialism. Today, the Brücke Museum in Berlin holds many of the group’s surviving works, but Dresden—where it all began—has also reclaimed its role in the movement’s genesis.

The city’s museums, particularly the Albertinum, now house major Expressionist holdings, and scholars continue to explore how Dresden’s urban environment, social climate, and academic rigidity helped birth one of Europe’s most disruptive and visionary art movements.

In the arc of Dresden’s art history, Die Brücke stands as a rupture and a revelation. These artists did not build palaces or decorate churches. They wielded paint and print like torches, lighting a path through a world on the brink. And in doing so, they extended Dresden’s legacy—not as a city frozen in beauty, but as one capable of radical reinvention.

Degenerate Art and the Nazi Era

Few chapters in Dresden’s art history are as fraught—or as consequential—as the years under National Socialist rule. Between 1933 and 1945, the city’s long-standing status as a cultural beacon collided with a regime that sought to reshape art into a weapon of ideology. The Nazis’ campaign against modernism—epitomized by the term “Entartete Kunst” (“degenerate art”)—cut through the core of Dresden’s artistic identity, targeting Expressionism, abstraction, and internationalism in favor of propaganda-laden classicism. The effects of this campaign were devastating: works were confiscated, artists were silenced, and entire aesthetic legacies were nearly extinguished.

By the time Hitler rose to power, Dresden’s museums held one of the finest collections of modern German art in the country. The Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, which oversaw institutions like the Albertinum and the Kupferstich-Kabinett, had been acquiring works by Caspar David Friedrich, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix, Paul Klee, Emil Nolde, and many others. While the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister showcased the grandeur of the past, the modern departments engaged with the ferment of contemporary aesthetics—often with strong local ties, especially through the legacy of Die Brücke.

But under the Nazi regime, modernism became synonymous with cultural decay. Hitler’s personal taste skewed toward academic realism and idealized neoclassicism—art that projected racial purity, strength, and national pride. Any deviation from these ideals was labeled degenerate, perverse, or “un-German.” In 1937, the Nazis launched a nationwide purge of museums and galleries, removing thousands of modernist works from public view.

In Dresden, the impact was swift and brutal. Over 700 modern works were confiscated from the state collections alone. The Kunstgewerbemuseum, Kupferstich-Kabinett, and Albertinum all lost substantial parts of their holdings. Masterpieces by Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Kokoschka, and Dix were seized and, in many cases, never returned. Some were burned in secret; others were sold abroad to finance the Nazi war machine.

One of the most chilling symbols of this cultural assault was the 1937 exhibition “Entartete Kunst”, first mounted in Munich and later shown in several cities. Though Dresden was not an official stop on the tour, the exhibit’s ideology pervaded the city’s cultural climate. Posters and public lectures warned against the dangers of abstraction and “Bolshevik aesthetics.” School curricula were rewritten to emphasize Aryan ideals. Art became a battlefield, and modernism was on the losing side.

Individual artists suffered alongside the institutions. Otto Dix, a Dresden professor and one of Germany’s most trenchant chroniclers of war and social collapse, was dismissed from his teaching post in 1933. His harrowing portraits of wounded veterans and decadent elites were deemed degenerate, and many of his works were destroyed or hidden. Ironically, Dix would survive the war and return to East Germany after 1945, but his artistic voice had been silenced during the regime’s peak.

Even more tragically, Jewish artists and collectors were subject to persecution, exile, or extermination. Their collections were plundered, their names erased from catalogues. Dresden’s Jewish community, which had played a vital role in the city’s intellectual and artistic life, was nearly annihilated in the Holocaust. The cultural losses went beyond buildings and paintings—they were human and irreparable.

Architecture, too, was marshaled into ideological service. While Dresden’s Baroque and Neoclassical heritage was co-opted by Nazi visual culture—idealized as a pure German past—the city itself was not a major site of the regime’s monumental building projects. Nevertheless, the emphasis on aesthetic order, hierarchy, and racial symbolism infiltrated public design, educational institutions, and art criticism. Artists who conformed to the new orthodoxy were promoted, while others were exiled to inner or outer oblivion.

The paradox of this era is that even as Dresden’s modernist collections were gutted, the city continued to serve as a symbol of German cultural superiority. The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, for example, was held up as a beacon of classical taste. The Nazis used it to promote their narrative of cultural lineage—linking the supposed racial purity of Renaissance masters to their own mythologized Aryan ancestry. Art was no longer about individual expression or public enrichment—it was propaganda, pure and simple.

The cultural consequences of this ideological cleansing were long-lasting. Many confiscated artworks never returned to Dresden’s walls. Others, now scattered in private collections or international museums, bear provenance gaps and restitution claims that remain unresolved. The trauma of the Nazi years severed Dresden’s continuity as a center of innovation, leaving a generation of artists and curators to rebuild in the wake of immense loss.

Yet even in this darkness, there were acts of quiet resistance. Some curators hid works in basements and storage rooms, protecting them from destruction. Art lovers and intellectuals, even under surveillance, continued to study banned books and paintings. The very survival of key figures like Otto Dix ensured that the story of resistance—artistic, moral, and spiritual—would not be completely erased.

In the postwar era, Dresden would become a city of ruins and remembrance, and its experience under the Nazis would inform how its museums, artists, and historians engaged with art. The reconstruction of Dresden’s artistic legacy involved not only bricks and mortar, but also a reckoning with complicity, censorship, and loss.

The chapter of “degenerate art” is not simply about repression—it’s about the fragility and resilience of artistic freedom. Dresden’s story during this time is a reminder of how easily culture can be bent to serve tyranny, and how powerfully it can endure when nurtured by conscience and memory.

Destruction and Devastation: The 1945 Bombing of Dresden

On the night of February 13, 1945, the skies above Dresden were torn open. In a series of bombing raids carried out by British and American forces, one of Europe’s most storied cultural capitals was reduced to ash. Over the next two days, wave after wave of high-explosive and incendiary bombs rained down upon the city, triggering a firestorm that incinerated vast swathes of Dresden’s historic core. Estimates of the death toll vary, ranging from 25,000 to over 35,000, but the symbolic loss was incalculable. Dresden—the “Florence on the Elbe,” the city of churches, palaces, and paintings—became a byword for the cultural cost of total war.

The destruction of Dresden was not an isolated tragedy, but it stands out in the annals of wartime history because of what was lost. For centuries, the city had been a center of artistic excellence. Its Baroque and Rococo architecture had survived Napoleonic invasions, its collections had weathered political change, and its museums were among the finest in Europe. What vanished in those fiery days of February was not only a physical city but also a centuries-old cultural ecosystem—buildings, artworks, libraries, archives, and human talent.

The Zwinger, the Royal Palace, the Semperoper, the Frauenkirche, and numerous churches, theaters, and historic neighborhoods were either obliterated or left as skeletal ruins. The Frauenkirche, in particular, became a potent symbol. This great Protestant dome, designed by George Bähr and completed in 1743, collapsed into rubble under the heat and pressure of the firebombing. Its blackened stones would lie in place for decades, a scar and a silent witness to catastrophe.

And yet, amidst the devastation, a quiet triumph of foresight and preservation emerged. Dresden’s curators and museum staff, acutely aware of the approaching Allied forces and the growing intensity of bombing across Germany, had already begun to evacuate many of the city’s priceless artworks. Paintings from the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, porcelain from the Zwinger, manuscripts, scientific instruments, and sculptures were transported to secure storage sites in Saxon castles and countryside bunkers. This effort, though imperfect, saved much of Dresden’s artistic legacy.

Nevertheless, what could not be moved—architectural heritage, frescoes, monumental sculptures, and site-specific works—was left vulnerable. The firestorm that engulfed the city did more than burn buildings; it incinerated context. Even if a painting survived, the room it once adorned, the gallery that contextualized it, the neighborhood that gave it meaning—these were erased.

The rationale for the bombing of Dresden remains one of the most debated actions of the Second World War. Strategically, the city had military value: it was a transportation hub, a communication center, and, despite its cultural renown, deeply embedded in the Nazi war machine. But critics have long argued that the scale and timing of the attack—just months before Germany’s surrender—rendered it less a tactical necessity and more a punitive demonstration of power. Churchill himself later expressed reservations about the extent of the destruction.

In the years immediately following the war, Dresden’s ruins became both a literal and symbolic battleground. Under Soviet occupation and later within the German Democratic Republic, the city was tasked with a monumental question: how should it rebuild? Should it restore what was lost, modernize entirely, or preserve the rubble as a warning? The answers varied by project. Some buildings, like the Semperoper and Zwinger, were painstakingly reconstructed using original plans and surviving fragments. Others, like the Frauenkirche, were left in ruins for decades as anti-war memorials before being finally rebuilt after reunification.

For the GDR, Dresden’s wartime suffering became a tool of ideological storytelling. The bombing was held up as a symbol of Western barbarity, proof of fascism’s destructive legacy and capitalist cruelty. In this framing, the ruins were politically charged—less about mourning lost art than indicting imperialism. And yet, under the ideological surface, many East German artists and intellectuals maintained a private, often spiritual connection to Dresden’s cultural past.

Artistic responses to the bombing were shaped by this tension. Some, like the sculptor Fritz Cremer, created allegorical works that addressed war and resilience. Others, including painters and poets, struggled with how to render such annihilation in visual terms. Otto Dix, who had survived both World Wars, returned to themes of destruction and moral desolation in his later work. His postwar paintings, though not always overtly about Dresden, carried the weight of a world shattered and disillusioned.

Internationally, Dresden’s bombing provoked a complex response. In Britain and America, initial triumphalism gave way to remorse and artistic reckoning. Writers like Kurt Vonnegut, who was a prisoner of war in Dresden during the bombing, memorialized the event in works like Slaughterhouse-Five, casting the city as a stage for absurdity and horror. In art and literature, Dresden became a symbol of civilization’s fragility—of how quickly beauty can be undone.

Today, Dresden’s rebuilt skyline tells a story of endurance, but it also asks us to remember. The Frauenkirche, painstakingly reconstructed with a mixture of original stones and modern materials, reopened in 2005 as both church and peace monument. The Dresden Memorial by Käthe Kollwitz, located in the crypt of the rebuilt structure, honors all victims of war and violence, transcending national boundaries. Meanwhile, museums like the Military History Museum, redesigned by architect Daniel Libeskind, confront the ethics of warfare through contemporary design and critical exhibition.

In this way, the bombing of Dresden is no longer just a wartime event—it is a permanent layer in the city’s cultural memory. The scars remain visible not only in stone but in the way Dresden presents, protects, and interprets its art. Every reconstructed building is a dialogue with absence. Every painting returned to the wall is a victory over erasure.

Dresden’s destruction was nearly total. Its recovery has been incremental, fragile, and fiercely debated. But its commitment to remembering—not just the splendor, but the loss—has become part of what makes its cultural life so powerful. In the ashes of 1945, a new identity was forged: not simply as a city of beauty, but as a city that refuses to forget.

Postwar Reconstruction and the GDR Era

The end of World War II left Dresden a shattered city—physically devastated, psychologically wounded, and culturally disoriented. Its skyline, once a silhouette of domes and spires, had been reduced to jagged outlines of ruins and smoke. Yet from this devastation arose not just a city reborn, but a stage on which one of the 20th century’s most paradoxical cultural projects would unfold: the reconstruction of Dresden under the auspices of the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

From 1945 onward, Dresden became part of East Germany, and its fate was entwined with the ideologies of socialism. The GDR saw itself as the heir to antifascism, a state rooted in the working class, built in opposition to the West, and deeply invested in the power of art and architecture to shape collective identity. In Dresden, that project was both practical and symbolic. The city would not only be rebuilt—it would be reinvented.

The Politics of Rebuilding

In the immediate postwar years, emergency housing and infrastructure took priority. Rubble was cleared by the so-called Trümmerfrauen, or “rubble women,” who sifted through debris to salvage bricks and stones for future construction. But even amid basic recovery, debates about the city’s future began. Should Dresden’s artistic heritage be restored? Or should a new socialist city rise from the ashes?

The answer, predictably, was both—and the contradiction between them would define Dresden’s GDR-era art and architecture. The government recognized Dresden’s cultural prestige, especially its international reputation for classical and Baroque art. Restoring institutions like the Zwinger, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, and Semperoper would serve both propaganda and diplomacy. But at the same time, East German planners and politicians were determined to imprint socialist ideals on the rebuilt city.

The result was a unique aesthetic hybrid: Socialist Classicism fused with meticulous historical reconstruction. The Zwinger Palace, destroyed in the 1945 bombing, was reconstructed with incredible care, reopening in stages between the 1950s and 1960s. So too was the Semperoper, which rose from rubble to reopen in 1985—an astonishing act of cultural continuity, with its interior faithfully restored from original plans.

Meanwhile, entirely new urban ensembles were being built just beyond the historic core. The Prager Straße development, for example, introduced a modernist pedestrian boulevard flanked by prefabricated high-rises, department stores, and monumental sculptures. This was the socialist city in its most utopian form: clean, rational, forward-looking. It was also, artistically, often at odds with Dresden’s historical self-image.

Art under Socialism: State, Control, and Resistance

In East Germany, all art was political. The Association of Visual Artists (VBK) and the Ministry of Culture maintained strict oversight of exhibitions, commissions, and teaching posts. Socialist Realism became the official style, modeled on Soviet precedents and meant to portray heroic workers, peaceful landscapes, and the march of progress. Abstract art, religious iconography, and Western-style experimentation were discouraged or outright banned.

And yet, Dresden’s artists found ways to work within—and around—these constraints. Some, like Lea Grundig, embraced the ideals of socialist art and used them to explore themes of antifascism and humanism. Others, including survivors of the war like Willi Sitte or Werner Tübke, created large-scale murals and paintings that combined socialist iconography with baroque visual language and technical virtuosity.

The Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden (HfBK), the city’s renowned art academy, became both a site of ideological training and quiet resistance. Professors taught students traditional techniques—drawing, etching, anatomy—while subtly encouraging formal innovation. A generation of East German artists was raised on the tension between official dogma and personal vision.

Some artists managed to explore expressionism or abstraction by cloaking their work in allegory or historical subject matter. Gerhard Richter, who was born in Dresden and trained at the HfBK, defected to West Germany in 1961 and would become one of the most influential contemporary painters of his time. But even those who remained in the East, like Strawalde (Jürgen Böttcher) or Max Uhlig, developed unique, modernist vocabularies—layered, gestural, and emotionally charged—within the tight boundaries of the state.

Dresden’s museums, meanwhile, navigated their own ideological balancing acts. While modernist and “formalist” works remained largely hidden, historical collections were promoted as symbols of national culture. The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister reopened in 1960, its Raphael, Rembrandt, and Rubens galleries positioned as embodiments of German greatness—acceptable because they predated capitalism and modernist decadence. Behind the scenes, curators continued to preserve and study banned or marginalized works, quietly maintaining the continuity of Dresden’s broader artistic identity.

Public Art and Propaganda

In the GDR, art moved beyond galleries and into the streets. Dresden’s reconstruction was marked by a proliferation of monumental public art, designed to inspire socialist consciousness. Mosaics, reliefs, and sculptures adorned housing blocks, factories, and public squares. These works often depicted muscular workers, wheat sheaves, hammers, and scenes of joyful collectivism. Many were the products of state-sponsored competitions and reflected the iconographic rigidity of the era.

Yet even within this prescribed language, some artists smuggled in nuance. The enormous mural “Der Weg der roten Fahne” (The Path of the Red Flag) by Heinz Drache and Gerhard Bondzin, once installed along the Kulturpalast, is a case in point. Ostensibly a heroic chronicle of proletarian struggle, it also hinted at deeper historical continuity and unspoken tensions.

As the 1980s drew to a close, economic stagnation and growing dissent across East Germany began to erode the ideological foundations of the GDR. In Dresden, unofficial art scenes began to emerge in student studios, private apartments, and underground exhibitions. Performance art, video, and conceptual installations—long suppressed—found quiet footing. Art once again became a language of protest.

Contemporary Dresden: Memory, Innovation, and Global Recognition

Emerging from the long shadows of war, dictatorship, and division, contemporary Dresden stands today as a city in dynamic conversation with its past. Its art scene, once dictated by monarchs and ministries, is now shaped by curators, collectives, and communities. While the city remains famous for its Baroque architecture and Old Masters, it is increasingly recognized for its bold contemporary culture, its architectural synthesis of old and new, and its commitment to remembrance and reinvention.

The Legacy of Reconstruction

The most visible symbol of Dresden’s cultural rebirth is the Frauenkirche. Reduced to rubble in the 1945 firebombing and left as a ruin during the GDR era, it was painstakingly rebuilt between 1994 and 2005, using both original stones and advanced digital modeling. The project was more than a restoration—it was a global effort, funded by donations from across the world and supported by craftspeople from both East and West Germany. The reconstructed church is not only a place of worship but also a monument to reconciliation, peace, and cultural memory.

The Neumarkt area surrounding the Frauenkirche has also been restored to echo its prewar urban layout, though not without controversy. Critics have questioned the aesthetics and historical fidelity of certain reconstructions, debating whether the city is reconstructing history or constructing nostalgia. But for many residents and visitors, these efforts represent a healing of the urban fabric—an attempt to bridge the rupture between past and present.

A Renaissance in the Arts

Dresden’s art institutions have not only recovered—they have flourished. The Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (SKD), the umbrella organization overseeing the city’s major museums, is one of the most ambitious in Europe. It manages twelve museums, including the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Albertinum, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Porzellansammlung, and Green Vault. Since reunification, the SKD has pursued a dual mission: to preserve its classical treasures while expanding its contemporary holdings and critical engagement.

The Albertinum, extensively renovated and reopened in 2010, now houses both 19th-century art and the Galerie Neue Meister, which presents modern and contemporary works. It brings together Caspar David Friedrich, Gerhard Richter, Otto Dix, and Georg Baselitz under one roof, allowing visitors to trace the evolution of German painting through centuries of upheaval. Special exhibitions frequently foreground underrepresented artists, global perspectives, and difficult historical dialogues.

Meanwhile, Dresden has cultivated a lively scene for contemporary and experimental art. The Ostpol and GEH8 art spaces, artist-run initiatives like Kunsthaus Raskolnikow, and the Motorenhalle project space offer platforms for performance, video, installation, and conceptual work. The Hellerau European Centre for the Arts, located in a former garden city outside Dresden’s center, has become one of Germany’s most important venues for contemporary dance, theater, and interdisciplinary arts.

These spaces are not isolated enclaves—they are deeply embedded in the city’s social and political debates. Artists in Dresden often engage with themes of memory, identity, ecology, and migration, reflecting Germany’s broader reckoning with its history and future.

Art, Memory, and Public Space

Dresden remains a city profoundly marked by its past, and public art has become a key medium through which that past is processed. The rebuilt Frauenkirche hosts peace concerts and exhibitions; the Military History Museum, redesigned by Daniel Libeskind, confronts Germany’s militarism with a jarring architectural intervention—his angular steel wedge slicing through the museum’s classical façade as a symbolic rupture.

Contemporary memorials, such as the Dresden Synagogue—a minimalist, abstract structure completed in 2001—mark absence as presence. Built on the site of the synagogue destroyed during Kristallnacht in 1938, it makes no attempt to reproduce the lost original, instead asserting a new spiritual and architectural identity.

Even ephemeral or controversial works have left their mark. In 2017, Syrian-German artist Manaf Halbouni erected three upended buses in front of the Frauenkirche, modeled after makeshift barricades used in Aleppo. The installation, titled Monument, sparked fierce debate—some saw it as a powerful gesture of solidarity and anti-war protest, while others criticized its placement or political implications. Yet the dialogue it generated underscored Dresden’s evolving identity: a city no longer content to be only a museum of the past, but an active site of critical reflection.

Challenges and Contradictions

Contemporary Dresden is not without its challenges. In recent years, the city has drawn international attention not only for its art but for political polarization. The rise of the far-right PEGIDA movement and populist sentiment in Saxony has raised uncomfortable questions about cultural identity, memory politics, and who “owns” the public narrative. Artists, curators, and cultural institutions have responded with exhibitions, talks, and performances that push back against xenophobia and historical revisionism.

Museums like the SKD have taken public stands, issuing statements affirming diversity, human rights, and openness. Cultural events like the Dresden Contemporary Music Days, Ostrale Biennale, and Trans-Media-Akademie Hellerau attract international talent and spotlight new forms of digital and participatory art. These platforms provide crucial spaces for dialogue and experimentation in a city often caught between heritage and renewal.

Dresden in the Global Eye

Today, Dresden is once again a destination for artists, scholars, and tourists from around the world. Its museums host traveling exhibitions in partnership with institutions like the Louvre, the Met, and the Hermitage. Its universities and academies welcome international students and researchers. Its art scene, while still finding balance between state support and independent vitality, contributes to the global conversation.

Perhaps what sets Dresden apart is the intensity of its relationship to time. Few cities wear their history so visibly—and few have been forced to confront it so honestly. In Dresden, art is never just decoration. It is architecture and archive, commemoration and confrontation, beauty and burden.

As the city continues to evolve, its art—old and new—will remain both mirror and guide. The tension between the Baroque and the brutalist, the Romantic and the radical, is not a flaw but a feature. It is what gives Dresden its depth, its resonance, and its lasting importance in the story of art history.

Conclusion: Dresden’s Cultural Palimpsest

Dresden is a city layered in time—its cultural identity not fixed, but rewritten again and again like a palimpsest, where no inscription is ever fully erased. Its art history reads not as a steady progression, but as a sequence of dramatic ruptures and resurrections. In this, Dresden does not merely reflect European art history—it embodies its contradictions.

At one level, Dresden is the city of Augustus the Strong, of porcelain palaces and Baroque opulence. Its Zwinger and Green Vault dazzle with the glitter of absolutism, expressions of an age when art was power. At another, it is the city of Caspar David Friedrich and the Romantic longing for the infinite—where the landscape became a reflection of the soul, and art turned inward.

Dresden is also the birthplace of Die Brücke, a cradle of German Expressionism, where color and form exploded under the pressure of modernity. It is the city where Kirchner, Heckel, and Schmidt-Rottluff revolted against the genteel past, forging an art of raw emotion and psychological depth. And it is the city where that art would be later denounced, confiscated, and nearly destroyed under fascism.

Then came fire. The bombing of Dresden in 1945 stands as one of the most potent symbols of cultural devastation in modern history. But it is in the ashes that Dresden’s most remarkable story begins: not merely of rebuilding walls, but of rebuilding identity. Under the constraints of the GDR, the city reasserted its artistic importance—restoring its museums, reimagining its institutions, and nurturing new voices under the watchful eye of ideology.

Since reunification, Dresden has become a space of reckoning. It has wrestled with memory, with guilt, with triumph, and with transformation. Its museums do not hide their scars. Its churches do not erase their ruin. Instead, Dresden’s art institutions present history as lived experience, asking visitors to see not only beauty but resilience, not only glory but the cost.

To walk through Dresden’s galleries is to move through centuries of ambition, trauma, and reinvention. It is to see the dazzling treasures of Augustus the Strong alongside the solitary monks of Friedrich, the broken faces of Otto Dix, and the reconstructed stones of the Frauenkirche. It is to feel the city’s pulse through its canvases, corridors, and cultural spaces.

Art in Dresden has never been neutral. It has always been bound to power, to ideology, to resistance. It has served emperors and challenged them, adorned propaganda and dismantled it, preserved tradition and exploded it. That tension is not an accident—it is the source of the city’s cultural vitality.

As Dresden looks to the future, its art history offers both caution and inspiration. It warns of what can be lost when culture is controlled, and it celebrates what can be reclaimed when people choose to remember, to rebuild, and to imagine again. Whether through the delicate touch of Meissen porcelain, the stark lines of a Kirchner woodcut, or the multimedia provocations of contemporary installations, Dresden continues to ask the oldest—and most urgent—questions of art: Who are we? What have we done? And what can we become?

Dresden is not a monument to art history. It is art history in motion.