The Die Brücke art movement was founded in 1905 in Dresden, Germany, by a group of young architecture students who sought to break away from traditional artistic norms. The founding members—Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff—were disillusioned with academic art and the rigid structures of the Wilhelmine era. These artists were deeply influenced by the rapid industrialization of Germany, which they felt alienated people from nature and true human expression. Their goal was to forge a new path in art, one that was unfiltered, raw, and deeply personal.

The name Die Brücke translates to “The Bridge”, symbolizing their mission to connect the old and the new in art. They saw themselves as pioneers, forging a bridge from traditional European styles to a more modern and emotionally charged form of expression. Their early influences included Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and the vivid colors of Vincent van Gogh. However, they also drew inspiration from African and Oceanic tribal art, which they admired for its simplicity, directness, and emotive power. By embracing these outside influences, Die Brücke artists sought to challenge the elitism of the European art world.

The group established their first studio in Dresden, where they lived and worked together, creating an almost utopian artistic community. They rejected the strict teachings of Dresden’s Academy of Fine Arts, preferring to experiment freely with form, color, and technique. Their work was often highly personal, reflecting their inner emotions rather than striving for realism. They believed in spontaneous, expressive art that could capture the intensity of modern life.

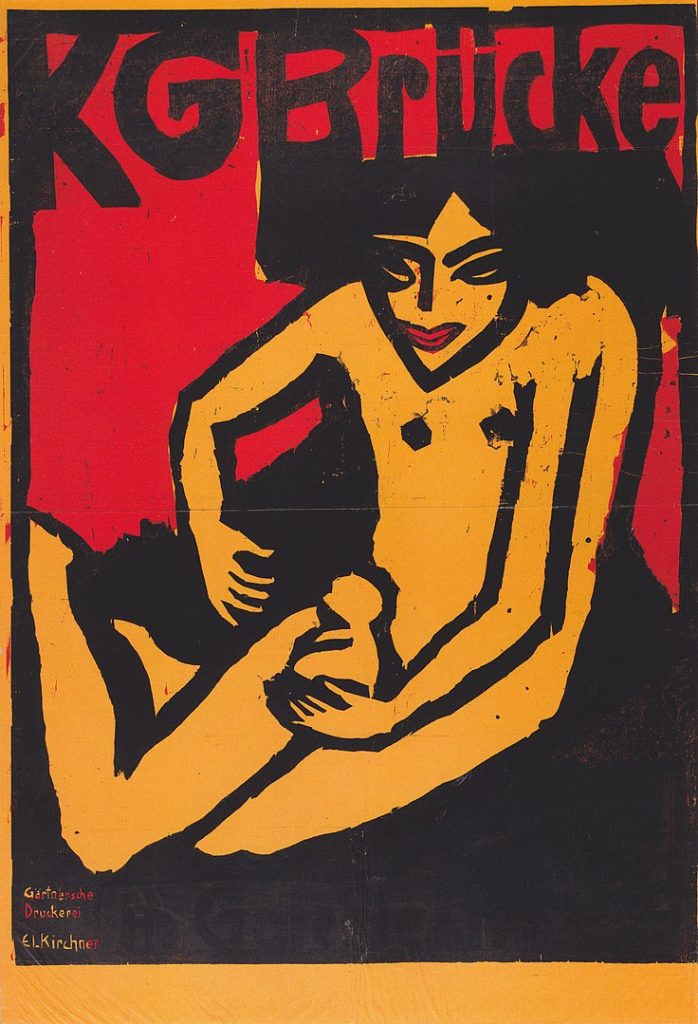

Despite their initial obscurity, Die Brücke’s bold and experimental approach quickly began attracting attention. They held their first exhibition in 1906, displaying works that were shocking to many viewers. Their use of harsh colors, distorted forms, and aggressive brushstrokes was a direct rejection of the polished, detailed academic painting style of the time. Though many critics dismissed them, the artists remained undeterred, determined to revolutionize German art.

The Vision and Philosophy of Die Brücke

At the heart of Die Brücke was a philosophy rooted in rebellion against tradition and an embrace of pure artistic expression. The artists were heavily influenced by the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, who championed the idea of breaking away from societal constraints to achieve true creative freedom. They saw themselves as revolutionaries in the art world, rejecting conventional techniques and subject matter in favor of bold, emotional, and unfiltered self-expression. Their movement was not just about painting—it was a lifestyle that encompassed radical social ideals, artistic experimentation, and a rejection of bourgeois norms.

The movement’s name, Die Brücke, reflected their desire to create a “bridge” between the past and the future, linking artistic traditions with a bold new vision. They sought to free art from the constraints of realism and instead embrace subjectivity, distortion, and psychological depth. In their eyes, traditional art had become stale and lifeless, catering to an upper-class audience that valued technical precision over emotional authenticity. Die Brücke aimed to shake up this system by producing art that was intense, immediate, and deeply felt.

Their lifestyle was just as radical as their artistic philosophy. The members of Die Brücke lived communally, embracing a bohemian way of life that rejected the formality and decorum of middle-class society. They often retreated to nature, particularly to the Moritzburg Lakes near Dresden, where they practiced nudism, believing that a return to nature was essential for true creative expression. This rejection of societal conventions was mirrored in their art, which frequently depicted nudes, dancers, and urban scenes filled with energy and movement.

Another defining element of their philosophy was their belief in the power of art to provoke emotional responses. They were not concerned with portraying things as they were but rather with capturing how they felt. By using exaggerated colors, distorted forms, and rough textures, they created works that were intentionally unsettling and deeply expressive. This belief in the emotional and psychological power of art would go on to influence later movements, including German Expressionism and Abstract Expressionism.

Key Artists of Die Brücke and Their Contributions

Among the founding members, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner emerged as the most influential figure, both as an artist and as a leader of the group. Kirchner’s work was characterized by bold, angular lines, exaggerated forms, and a vibrant but unsettling use of color. His paintings often depicted Berlin’s fast-paced urban life, reflecting the tension and alienation that came with modernization. Works like Street, Berlin (1913) showcased his mastery of expressionist techniques, with its jagged figures and electric hues capturing the anxiety of city life.

Erich Heckel was another key member whose work focused on emotionally charged woodcuts and moody figurative paintings. He experimented heavily with printmaking, particularly woodblock prints, which allowed for stark contrasts and expressive line work. His piece Young Girl (1910) demonstrated his ability to create deeply emotional portraits with minimal detail, using just a few sharp lines and a bold color palette to convey psychological depth. Heckel’s contributions helped establish printmaking as a significant part of Die Brücke’s artistic legacy.

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff was known for his use of intense color and simplified forms, often verging on abstraction. His paintings and prints explored geometric shapes, flattened perspectives, and dynamic compositions, elements that would later influence modern graphic design. His works, such as Houses at Night (1912), showcased a deep fascination with structure and rhythm, reducing cityscapes to pure shapes and colors. His ability to balance structure with emotional intensity made him a crucial figure in the movement.

Later, Emil Nolde became associated with Die Brücke, though he was never an official member. His deeply expressive use of color and themes of religious mysticism and raw human emotion aligned with the movement’s ideals. Works like The Last Supper (1909) pushed the boundaries of traditional religious painting, transforming a well-known biblical scene into an emotionally charged, almost nightmarish vision. Though Nolde later distanced himself from Die Brücke, his work remained a powerful extension of the movement’s ideals.

Die Brücke’s Unique Artistic Style and Techniques

Die Brücke’s art was defined by bold, unnatural color choices, sharp contrasts, and exaggerated, distorted forms. Their paintings often featured bright, clashing colors that heightened the emotional impact of their work. Unlike Impressionists, who sought to capture fleeting moments of light and atmosphere, Die Brücke artists focused on expressing raw emotion. This resulted in a harsh, almost aggressive aesthetic that set them apart from their contemporaries.

One of the most distinctive techniques used by Die Brücke was woodcut printing, which allowed for bold, graphic compositions with sharp, angular lines. This technique was inspired by traditional German medieval prints as well as African tribal art, which the artists admired for its directness and symbolic power. Their woodcuts often depicted stark, expressive faces and highly simplified figures, emphasizing the emotional core of their subjects.

The movement’s paintings often portrayed urban life, cabaret dancers, and street scenes, as well as more tranquil images of nature and nude figures. This contrast reflected their dual fascination with both modern civilization and the primitive, untamed world. They frequently painted in outdoor settings, using loose brushwork and thick, impasto layers of paint to create a dynamic, immediate feel.

Compositionally, Die Brücke artists rejected classical perspective and realism, instead using flattened spaces, jagged outlines, and fragmented forms. Their figures often appeared awkward or contorted, reflecting the psychological intensity of their themes. These stylistic choices made their work feel raw, emotional, and sometimes unsettling, a clear departure from the polished techniques of academic painting.

Major Works and Exhibitions of Die Brücke

Die Brücke artists produced some of the most iconic and influential works of early 20th-century German Expressionism. Their paintings, prints, and woodcuts were characterized by distorted forms, vivid colors, and emotionally charged subject matter. One of the most famous works from this period is “Street, Berlin” (1913) by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, which depicts the chaotic energy of urban life through jagged lines, elongated figures, and harsh, unnatural colors. This painting reflects Kirchner’s fascination with the fast-paced, alienating experience of modern city life, a recurring theme in Die Brücke’s art.

Another key piece is “Bathers at Moritzburg” (1909) by Kirchner, which showcases the movement’s connection to nature and the human body. The painting captures a group of nude figures in an outdoor setting, rendered in broad, expressive brushstrokes and exaggerated forms. It highlights Die Brücke’s rejection of social constraints and their belief in the liberating power of natural living. The emphasis on nudity and raw physicality was meant to symbolize a return to a more primal and authentic existence, free from the suffocating norms of urban society.

Erich Heckel’s “Young Girl” (1910) is another defining work that embodies the group’s experimental style. The portrait features a simplified, angular face with intense, staring eyes, reflecting the psychological depth that was central to Die Brücke’s artistic philosophy. The woodcut technique, with its harsh contrasts and bold outlines, gives the piece a stark, almost primitive quality. Heckel’s prints became highly influential, paving the way for later developments in graphic design and political poster art.

Die Brücke artists actively organized exhibitions to promote their revolutionary style, despite facing rejection from the mainstream art world. Their first major group exhibition took place in 1906 in Dresden, where they displayed paintings and prints that shocked traditional audiences. In 1910, they published the Brücke Almanach, a manifesto-like publication that outlined their artistic philosophy and included reproductions of their works. By 1911, the group had relocated to Berlin, where they continued to exhibit independently after being rejected by the Berlin Secession, a conservative artistic association. These exhibitions helped establish their reputation, though many critics viewed their work as crude and unpolished.

The Decline and Disbandment of Die Brücke

By 1913, tensions within the group led to Die Brücke’s dissolution. While they had shared a common vision in their early years, differences in artistic direction and personal conflicts began to emerge. Some members wanted to move towards a more individualized and introspective approach, while others still sought to maintain the collective spirit of the movement. The pressures of urban life in Berlin, where they had relocated, also contributed to their growing disillusionment. The intense competition in the art scene and their struggle for financial stability further strained their unity.

World War I also played a significant role in the group’s decline. Many of the artists, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, were drafted into military service, which profoundly affected their mental and physical well-being. Kirchner, in particular, suffered a nervous breakdown in 1915 and was later discharged due to psychological distress. His later works took on an even darker, more fragmented style, reflecting his trauma from the war. The war also disrupted the German art world, making it difficult for avant-garde artists to continue their work in the same capacity.

Another major blow came in the 1930s, when the Nazi regime labeled Expressionist art as “degenerate” and banned many of the movement’s works. Several Die Brücke artists, including Kirchner, saw their paintings removed from museums and destroyed by the Nazis. Kirchner, who had already been battling depression and declining health, took his own life in 1938, marking a tragic end to one of the movement’s most influential figures. Other members, like Schmidt-Rottluff and Heckel, continued to work in Germany but faced increasing oppression under the regime.

Despite its relatively short lifespan, Die Brücke’s influence did not disappear. Many of the surviving artists continued their work independently, and their stylistic innovations helped shape the later development of German Expressionism, Abstract Expressionism, and even modern graphic design. Their commitment to emotional intensity and artistic freedom laid the groundwork for generations of artists who sought to break free from academic traditions.

The Lasting Legacy of Die Brücke in Modern Art

Even though Die Brücke was disbanded in 1913, its impact on modern art remains profound. The movement was a crucial precursor to German Expressionism, inspiring later artists such as Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, and George Grosz, who continued to explore themes of psychological depth and social critique. The intense emotionalism and bold aesthetic choices pioneered by Die Brücke helped shape the later movements of Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism, particularly in the United States. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning drew upon the group’s unrestrained, expressive brushwork in their own abstract compositions.

Die Brücke also had a significant impact on film and graphic design. The visual language of the movement—characterized by high-contrast compositions, distorted figures, and emotionally charged imagery—influenced early German Expressionist cinema, including classic films like “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” (1920) and “Nosferatu” (1922). The group’s bold use of woodcut prints and simplified, angular forms also contributed to the development of modern graphic design, including political posters and advertisements that used strong contrasts and minimalistic design to create powerful visual messages.

In the post-war period, Die Brücke’s work was re-evaluated and given the recognition it had long been denied. In 1967, the Brücke Museum in Berlin was established to house and exhibit their works, ensuring that their artistic contributions would not be forgotten. Today, their paintings, prints, and drawings are displayed in major museums around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Albertina Museum in Vienna. Their art continues to inspire new generations of artists, curators, and historians, who see Die Brücke as a critical force in the evolution of modern art.

Despite the challenges they faced in their lifetime, the legacy of Die Brücke remains undeniable. Their commitment to breaking free from convention, embracing raw emotion, and challenging the status quo makes them one of the most influential artistic movements of the 20th century. Their work serves as a testament to the enduring power of art to provoke, inspire, and challenge societal norms, proving that true creativity is always a force to be reckoned with.

Key Takeaways

- Die Brücke was founded in 1905 in Dresden by Kirchner, Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff, and Bleyl as a radical break from academic art.

- Their art used bold colors, distorted forms, and strong contrasts to express intense emotion.

- Key artists included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and later Emil Nolde.

- The group disbanded in 1913, but their ideas heavily influenced German Expressionism and later movements.

- Their work was condemned by the Nazis in the 1930s but is now recognized as a major contribution to modern art.

FAQs

- What does “Die Brücke” mean?

“Die Brücke” means “The Bridge” in German, symbolizing a connection between traditional and modern art. - What are the characteristics of Die Brücke art?

Their art is known for vivid colors, distorted forms, expressive brushwork, and emotional intensity. - Why did Die Brücke dissolve?

Internal conflicts and diverging artistic paths led to their disbandment in 1913. - How did World War I impact Die Brücke artists?

Many members, including Kirchner, suffered mental and physical hardships due to the war. - Where can I see Die Brücke artworks today?

Major museums like MoMA, the Tate Modern, and the Brücke Museum in Berlin feature their works.