Long before Copenhagen became the cultural and political center of Denmark, it was a modest fishing village known as Havn, whose fortunes began to change in the 12th century. With the strategic blessing of Bishop Absalon—who is credited as the city’s founder—Copenhagen became not only a military outpost but also a site of ecclesiastical importance. This clerical influence shaped its earliest artistic traditions, which were deeply rooted in Christian iconography and devotional practices. The art of medieval Copenhagen was thus inseparable from the institutions of the Church, whose needs and aesthetics guided much of what was created.

Art as Devotion: Churches and Monasteries as Cultural Hubs

Copenhagen’s earliest art was produced for religious settings: altar pieces, frescoes, sculptures, illuminated manuscripts, and stained glass. In an era when literacy was limited and scripture was Latin-bound, visual art served as the primary means of religious instruction and spiritual reflection. The city’s churches, most notably the Church of Our Lady (Vor Frue Kirke), became repositories for such art.

These churches were often constructed in the Romanesque style, later transitioning to Gothic influences, with high vaulted ceilings and pointed arches designed to evoke heavenward transcendence. Wall paintings—many of which have been lost or uncovered only in fragments—depicted biblical scenes, saints, and moral allegories. These were not just decorative; they were pedagogical tools, designed to bring the holy narratives to life.

One significant example of early ecclesiastical art in Copenhagen can be seen in the remnants of the Franciscan and Dominican monasteries, where monks created and preserved religious texts. The Copenhagen Psalter, an illuminated manuscript from the 12th century (likely produced outside the city but preserved in the region), reflects the high craftsmanship and the theological symbolism of the time, with its richly colored initial letters and miniature scenes.

Materiality and Meaning

Stone, wood, and pigment were the materials of sacred storytelling. Copenhagen’s art of the medieval period emphasized symbolic meaning over naturalistic representation. Figures were stylized, proportions altered to convey hierarchy and divinity—Christ or the Virgin Mary would often be rendered larger than surrounding figures, signaling their importance. Gold leaf, where used, was not simply decorative but imbued with spiritual significance, representing divine light.

Sculptures were particularly prominent—often carved in wood or stone for use in altar pieces or exterior decoration. A notable surviving example is the Christus Rex (Christ the King) type, a recurring figure in Danish ecclesiastical art showing Christ as both crucified and reigning, a theological image resonant in both Catholic and later Lutheran traditions.

Copenhagen and the Hanseatic World

Though Copenhagen was not as commercially dominant as Lübeck or Hamburg during the medieval period, it was still part of the Hanseatic League’s maritime network. This connection meant that artistic ideas and materials—such as pigments, altar panels, and even itinerant artists—flowed through the city. Thus, while much of early Copenhagen art was local in production and purpose, it bore the influences of German, Dutch, and even English styles.

This cultural exchange enriched the visual vocabulary of local artisans. In particular, North German brick Gothic architecture left a lasting imprint on ecclesiastical buildings in Copenhagen and Zealand at large. The use of red brick became characteristic of Danish sacred architecture—practical due to local materials, but also aligned with aesthetic trends seen across the Baltic.

The Black Death and Artistic Shifts

Like much of Europe, Copenhagen was devastated by the Black Death in the mid-14th century. Artistic production slowed, and themes of mortality, repentance, and eschatology took on new urgency. Danse Macabre imagery and apocalyptic iconography became more common in church frescoes and manuscript margins. Art was still created, but it was increasingly preoccupied with death and divine judgment—reflecting a society in the grip of plague and religious anxiety.

Legacy and Preservation

Unfortunately, very little medieval art in Copenhagen survived the Reformation intact. During Denmark’s Lutheran Reformation in the early 16th century, iconoclasm led to the destruction or removal of many religious images, particularly those deemed “idolatrous.” Altars were stripped, statues smashed, and murals whitewashed. Ironically, it is often through the scars of this destruction that historians have uncovered fragments of the past—relics of paint behind plaster, carvings hidden behind later additions.

Today, the National Museum of Denmark and the SMK (Statens Museum for Kunst) house some of the surviving examples of this early period, including sculpture fragments and manuscript pages. Meanwhile, archaeological efforts continue to reveal the artistic bones of medieval Copenhagen buried beneath centuries of development.

The Renaissance in Denmark: Christian IV and the Rise of Royal Patronage

If medieval Copenhagen’s artistic energy pulsed from the cloisters and cathedral walls, the Renaissance shifted the spotlight toward royal courts and secular splendor. No figure embodies this transformation more than King Christian IV, who reigned from 1588 to 1648 and reshaped Copenhagen into a city of learning, architecture, and visual opulence. Under his rule, art in Denmark experienced a profound evolution—from the austerity of late medieval religious imagery to a courtly culture of portraiture, allegory, and monumental design.

Christian IV: A King with an Eye for Grandeur

Christian IV was one of Denmark’s most ambitious monarchs—visionary, energetic, and deeply invested in elevating the kingdom’s status through the arts. His reign coincided with the broader spread of Renaissance humanism across Northern Europe, and he seized upon these ideals to craft a new identity for Copenhagen. While Italian Renaissance aesthetics arrived somewhat later in Denmark than in southern Europe, their impact under Christian’s rule was no less transformative.

The king envisioned Copenhagen not just as an administrative center, but as a cultural capital worthy of the Danish crown. This vision materialized in grand building projects, the recruitment of foreign artists and architects, and the cultivation of a court that prized elegance and erudition.

Architecture as Power: The King’s Urban Legacy

Christian IV’s most enduring artistic legacy lies in architecture. He was a patron in the truest Renaissance sense: commissioning buildings that projected royal authority, intellectual sophistication, and cosmopolitan taste. Among the most famous of his projects are:

- Rosenborg Castle (1606–1624): A jewel of Dutch Renaissance design, this castle was both royal residence and a statement of refinement. It blended red brick façades with ornate sandstone details and gabled towers—features emblematic of the Dutch influence on Danish architecture during this period. Inside, it housed tapestries, portraits, and fine furniture that reflected Christian’s eclectic taste.

- The Round Tower (Rundetårn): Completed in 1642, this astronomical observatory was part of Christian’s broader project to promote science and learning. The tower, with its unique spiral ramp and Renaissance design, still stands as a symbol of intellectual ambition married to architectural ingenuity.

- Børsen (the old Stock Exchange): With its iconic dragon-spire rooftop, this building combined economic function with stylistic flourish. It was a physical manifestation of Denmark’s trading ambitions, mirroring Christian IV’s desire for Copenhagen to rival cities like Amsterdam and Hamburg.

Dutch Influence and Imported Talent

Denmark in the early 17th century was not isolated. The king actively invited Dutch, German, and Flemish artists, engineers, and craftsmen to Denmark, ensuring that Copenhagen’s transformation aligned with European tastes. The Dutch, in particular, had a significant impact, introducing a refined architectural vocabulary and painting styles centered on realism and the careful study of light.

Artists such as Abraham Wuchters and Karel van Mander the Younger were brought to court to paint portraits of the royal family and Danish nobility. These portraits, often staged with regal symbolism and richly rendered attire, were not only exercises in flattery—they functioned as tools of propaganda, affirming Christian IV’s status as a cultured and capable monarch.

The Rise of Court Portraiture and Secular Themes

Before Christian IV, Danish art was still primarily ecclesiastical. But under his patronage, a new genre flourished: portraiture. These works celebrated individual identity, lineage, and worldly power rather than spiritual virtue.

Christian’s own likeness was captured countless times, often in armor or elaborate garments. One surviving painting by Pieter Isaacsz shows the king as both soldier and sovereign—a nod to his military ambitions and his desire to be seen as a Northern Renaissance prince in the mold of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden or the Holy Roman Emperor.

Alongside portraits, allegorical art gained popularity at court. These paintings, often dense with symbols and mythological references, projected ideals of virtue, wisdom, and divine right. Artists were expected not only to depict but to flatter and idealize, using the languages of classical mythology and biblical allusion to elevate their patrons.

Art in Service of Empire and Expansion

Christian IV’s aspirations weren’t confined to aesthetics—he saw art and architecture as vehicles for geopolitical ambition. As Denmark sought to expand its influence in the Baltic and North Atlantic, its capital needed to reflect imperial stature. The visual culture of Copenhagen became a form of soft power, crafted to impress foreign dignitaries, promote trade, and secure alliances.

Moreover, the king invested in civic beautification: fountains, public squares, and statues were erected to glorify the monarchy and promote civic pride. While many of these structures have not survived, their influence endures in the city’s spatial layout and stylistic DNA.

Legacy and Later Reassessment

Christian IV died in 1648, having ruled for 60 years—longer than any other Danish monarch. Though his later years were marred by military defeats and economic strain, his artistic legacy is undisputed. He turned Copenhagen into a stage for Renaissance culture, blending Northern European styles with a uniquely Danish sensibility.

Today, many of his buildings still define Copenhagen’s architectural landscape. Rosenborg Castle is now home to the Danish Crown Jewels, and the Round Tower continues to attract visitors from around the world. More importantly, Christian IV set a precedent for state-sponsored art and architecture—a model that later monarchs, and even modern Danish governments, would follow.

Baroque Splendor and the Age of Absolutism

As the Renaissance ideals nurtured by Christian IV matured into the 17th and early 18th centuries, Copenhagen entered an era defined not just by aesthetics, but by power—absolute power. The Baroque period in Denmark, as in much of Europe, was an artistic expression of royal authority, religious orthodoxy, and dynastic ambition. In Copenhagen, the visual language of the Baroque became the architecture of control: dramatic, ornate, and unambiguously majestic.

From Renaissance Rationality to Baroque Spectacle

While Christian IV had introduced classical symmetry and intellectual refinement into the visual culture of Copenhagen, his successors embraced grandeur, theatricality, and emotional resonance. The Baroque in Denmark was less flamboyant than in Italy or France, but it adapted the style’s essentials: dynamic architecture, expressive sculpture, and symbolic ornamentation.

This period coincided with the consolidation of absolute monarchy in Denmark, which was formalized in 1660 under Frederick III. Henceforth, kings ruled not by consensus but by divine right. Art became a direct servant of the state, visualizing authority not only in palaces and portraits but in the very layout of the city.

Frederiksstaden and the Geometry of Control

One of the clearest examples of Baroque planning in Copenhagen is the later Frederiksstaden district, initiated in 1749 under Frederick V (though stylistically more Rococo, its layout remains deeply rooted in Baroque principles). This carefully planned neighborhood—centered on the grand, octagonal Amalienborg Palace complex—was designed to project royal power and cosmopolitan elegance.

It’s a masterclass in Baroque urban planning: axial symmetry, open sightlines, and monumental scale. Four palatial mansions surround a central square, anchored by a statue of King Frederick V. The district aligned royal power with divine order—every vista reinforcing hierarchy and grandeur.

Church of Our Saviour: Baroque Drama in Brick and Gold

One of Copenhagen’s architectural gems of the Baroque era is the Church of Our Saviour (Vor Frelsers Kirke), completed in 1695. Its dramatic spiral spire, wrapped in a golden staircase, embodies the aspirational spirit of Baroque design: a literal ascent toward the heavens. Climbing it is not only a physical journey but a metaphorical pilgrimage, characteristic of Baroque spirituality.

Inside, the church houses gilded altarpieces, carved pulpits, and complex organ façades—each element part of a coordinated visual theology meant to overwhelm the senses and draw the viewer into ecstatic contemplation.

Court Painters and the Embodiment of Monarchy

Portraiture continued to flourish, now layered with deeper symbolism and theatrical flourish. One prominent figure was Justus van Effen, who painted numerous court portraits during the reign of Frederick IV. These paintings present the king as both worldly and sacred, wrapped in velvet robes, framed by columns and drapery, and surrounded by insignia of state—orb, scepter, crown.

Baroque portraiture was no longer just about likeness; it was about projection. Each detail in these compositions—whether the presence of a globe (imperial aspiration) or a battlefield (military strength)—was carefully chosen to assert dynastic legitimacy.

Decorative Arts and the Gesamtkunstwerk

The Baroque period in Copenhagen saw a flowering of decorative arts, particularly in palace interiors. Stucco ceilings, gilded paneling, painted murals, and elaborate tapestries worked together to create a Gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art that fused architecture, painting, sculpture, and design into a unified visual experience.

Rosenborg Castle, though begun under Christian IV, was lavishly updated during this period, especially in its interiors. Its Great Hall was adorned with elaborate ceiling frescoes and throned lions—symbols of Denmark’s martial pride and divine kingship. Each room became a kind of theater, designed not only for function but for spectacle.

The Role of the Church: Baroque Piety in Lutheran Denmark

Though Denmark was a staunchly Lutheran nation after the Reformation, Baroque religious art did not vanish—instead, it adapted. Danish churches began to embrace a sober yet majestic interpretation of Baroque decor, emphasizing clarity, order, and divine grandeur over the emotional intensity seen in Catholic regions.

Altarpieces became central visual features—often large-scale paintings framed by carved wood or gilded panels, with Christ as the triumphant centerpiece. Organ cases became particularly ornate, symbolizing both musical praise and visual magnificence.

Opera, Theater, and Court Entertainment

Beyond architecture and painting, the Danish Baroque was rich in performance culture. The royal court sponsored ballets, operas, and court masques, where visual splendor met musical and theatrical innovation. Costumes, stage sets, and performance design were part of the artistic ecosystem.

The founding of the Royal Danish Theatre in 1748 marked a significant moment: the state’s embrace of the performing arts as an extension of court culture. Its productions, though accessible to the public, were laden with the aesthetics of aristocratic taste.

Copenhagen’s Artistic Identity in the Northern Baroque

While Denmark’s Baroque was never as ostentatious as that of Versailles or Vienna, Copenhagen’s adaptation of the style was no less potent. It synthesized the Protestant values of restraint and intellectualism with the Baroque’s love of order and magnificence.

This subtle version of the Baroque came to define Copenhagen’s identity: elegant rather than overpowering, rational rather than wild, but always deeply imbued with symbolism and spectacle. It was a visual language that conveyed Denmark’s unique place in Europe—a kingdom seeking prestige, stability, and divine favor through art.

The Danish Golden Age: Romanticism and National Identity (1800–1850)

If the Baroque expressed the splendor of monarchy and state, the Danish Golden Age marked a turn inward—toward nature, the self, and the soul of a nation. Between 1800 and 1850, Copenhagen became the crucible for a unique artistic flowering that would come to define Danish identity for generations. It was a moment when painters, poets, philosophers, and architects worked in parallel, deeply engaged with the ideals of Romanticism yet rooted in local landscapes and histories. This wasn’t just a flourishing of aesthetics—it was a cultural awakening.

Context: War, Loss, and National Reflection

The Golden Age arose from turbulent beginnings. The early 19th century was a time of crisis for Denmark. The Napoleonic Wars had devastated the country—Copenhagen was bombarded by the British navy in 1807, and Denmark lost Norway to Sweden in 1814. These traumas shook national confidence, yet they also catalyzed a search for meaning and stability.

Artists and intellectuals responded not with despair but with introspection. Where Baroque art glorified rulers and empire, the Golden Age turned toward the ordinary and the eternal: the Danish countryside, the quiet dignity of rural life, the domestic interior, and the moral strength of individuals.

Eckersberg and the Birth of a New Vision

The father of the Danish Golden Age was Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783–1853), a painter and professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Trained in Paris under Jacques-Louis David, Eckersberg returned to Denmark imbued with a Neoclassical rigor that he blended with a poetic sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

He is perhaps best known for his View from the Artist’s Window (c. 1830), a quiet yet luminous work that distills the era’s sensibility: clarity, serenity, and a reverence for the everyday. Eckersberg encouraged his students to observe the world directly—to sketch outdoors, study anatomy, and master perspective. His influence created a generation of painters who formed the core of the Golden Age.

The Artists: A School Rooted in Observation and Feeling

Eckersberg’s students included some of the most beloved names in Danish art:

- Johan Thomas Lundbye and P.C. Skovgaard elevated the Danish landscape to a national icon. Their pastoral scenes of rolling hills, beech forests, and still lakes weren’t just pretty—they were expressions of national pride and spiritual solace.

- Wilhelm Bendz and Wilhelm Marstrand brought psychological depth to portraiture and genre scenes. Their works often explored the inner lives of artists and intellectuals, reflecting Copenhagen’s growing cultural sophistication.

- Christen Købke, one of the most celebrated painters of the era, created deeply intimate and atmospheric works. His View of Lake Sortedam (1838) and Portrait of the Artist’s Mother embody the quiet, meditative beauty that defined the period.

These artists were not iconoclasts or revolutionaries. Instead, they sought harmony—between man and nature, the past and the present, the personal and the national. Their art offered a sense of rootedness in a time of uncertainty.

Philosophy, Poetry, and the Intellectual Climate

The Golden Age was not confined to the visual arts. Copenhagen was teeming with intellectual energy, fueled by figures like:

- Søren Kierkegaard, whose existential philosophy mirrored the introspective mood of Golden Age painting. His writings, though often abstract, resonated with the same search for truth and meaning.

- Hans Christian Andersen, whose fairy tales, though written for children, explored themes of loneliness, transformation, and beauty with Romantic sensibility.

- N.F.S. Grundtvig, theologian and educator, whose ideas about national culture and folk heritage deeply influenced both public life and artistic themes.

Painters and writers often moved in the same circles, frequenting salons and cafés, reading each other’s work, and shaping a shared cultural narrative rooted in Danishness—not in the nationalist fervor of empire, but in the poetry of place and memory.

Interiors and Intimacy: Domestic Space as Art

One of the striking features of Danish Golden Age painting is its attention to the interior. Artists like Vilhelm Hammershøi (though he would rise later in the 19th century) inherited this tradition of capturing domestic tranquility. Earlier painters created carefully balanced compositions of sunlit rooms, window views, and quiet activities—spaces where time seemed suspended.

These works were often infused with a Protestant ethic of humility, order, and reflection. They celebrated the everyday—not through grandiosity, but through attentive looking.

Architecture and the Classical Revival

The period also saw a classical revival in architecture, influenced by German and French Neoclassicism but adapted to Danish scale and sensibilities. Architect C.F. Hansen was a key figure, responsible for the reconstruction of The Church of Our Lady (Vor Frue Kirke) after the British bombardment. His restrained, temple-like design symbolized both resilience and order.

Public buildings, like the Copenhagen City Hall and parts of the University of Copenhagen, echoed ancient forms while reinforcing the Enlightenment ideals of reason, learning, and civic pride.

Nationalism Without Bombast

What makes the Danish Golden Age unique—especially in contrast to more turbulent nationalist movements elsewhere in Europe—is its gentle patriotism. Rather than depicting epic battles or heroic martyrs, Danish artists found national identity in subtlety: a farmhouse at dusk, a boy reading by the window, a forest path in late spring.

These images cultivated a shared emotional vocabulary, allowing Danes to see themselves reflected in a common landscape and moral tradition.

Legacy and Influence

The influence of the Danish Golden Age cannot be overstated. Its values—clarity, humility, intimacy, and observation—have permeated Danish art and design ever since. Modern icons like Hammershøi, Carl Nielsen, and even the minimalist aesthetic of Danish Modern furniture design carry forward its spirit.

Today, Golden Age works form the backbone of collections at the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) and Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, offering visitors a window into the serene yet profound soul of 19th-century Copenhagen.

Art Academies and Institutions: The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts

In the heart of Copenhagen’s historic district, nestled among neoclassical facades and cobblestone courtyards, stands one of the most influential cultural institutions in Denmark: The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi). Founded in 1754, the Academy has played a pivotal role in shaping not just the trajectory of Danish art, but the very idea of what it means to be an artist in Denmark. From the Neoclassical order of its Enlightenment roots to the pluralism of contemporary practices, the Academy has been both a bastion of tradition and a crucible for innovation.

Origins in Enlightenment Ideals

The Academy was established under King Frederick V during a time when Denmark was aligning itself with Enlightenment values—reason, education, and the cultivation of national excellence. It was part of a broader effort to institutionalize culture and knowledge, along with the founding of the Royal Theatre and the University of Copenhagen’s modern reforms.

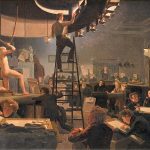

Modeled on the French Académie royale and similar institutions in Rome and Berlin, the Danish Academy was founded to professionalize art, provide systematic training, and elevate the status of artists beyond that of craftsmen. Prior to this, artistic instruction was largely conducted through guilds or workshops. The Academy introduced a new path: rigorous study in anatomy, perspective, classical sculpture, and history painting.

From the beginning, the Academy was designed not only as a school but as a symbol of cultural prestige—a place where art met ideology, and the cultivation of beauty served the greater civic good.

Nicolai Abildgaard and the First Generation of Danish Academic Painters

One of the Academy’s earliest and most influential professors was Nicolai Abildgaard (1743–1809), a painter deeply inspired by Neoclassicism and the ideals of the Enlightenment. Abildgaard brought a moral and intellectual gravity to the curriculum, urging students to see themselves as educators and philosophers, not just image-makers.

His paintings, often large-scale allegories or mythological scenes, drew from classical antiquity but were infused with contemporary political concerns. He admired the radicalism of the French Revolution and believed in the transformative power of art. Abildgaard’s pedagogy emphasized both technical skill and conceptual ambition—a duality that still characterizes the Academy today.

Eckersberg’s Reforms: Observation, Perspective, and Nature

If Abildgaard established the philosophical tone, C.W. Eckersberg, as professor and later director, cemented the Academy’s pedagogical methods. Taking his cues from both Neoclassicism and early Romanticism, Eckersberg restructured the curriculum to include live drawing from nude models, studies of perspective, and—most innovatively—plein air painting, or painting outdoors from direct observation.

This marked a radical departure from the reliance on idealized classical forms. Under Eckersberg, students were encouraged to look at the world around them: the Danish landscape, the human figure in motion, the subtle play of light and shadow. This approach laid the foundation for the Golden Age of Danish Painting and became a model for art education across Scandinavia.

The Academy as Cultural Authority

Throughout the 19th century, the Royal Danish Academy functioned not just as a school but as a gatekeeper of cultural legitimacy. The works it sanctioned and the artists it endorsed often dictated national tastes. Its annual juried exhibitions at Charlottenborg Palace, where the Academy is still housed, became prestigious events that defined success or failure for emerging artists.

Graduating from the Academy conferred social respectability. Many of the era’s top painters—Jens Juel, Christen Købke, Wilhelm Bendz, and P.C. Skovgaard—were Academy-trained, and their careers were inextricably linked to the institution’s patronage system. The Academy also operated an influential travel grant program, sending promising students to Italy, France, or Germany to study the Old Masters and bring back fresh ideas.

Challenges to Academic Orthodoxy: Modernism and the Avant-Garde

By the late 19th century, however, the Academy’s authority began to be questioned. New generations of artists found its classical constraints too limiting. The rise of Impressionism, Symbolism, and later Expressionism in Europe created rifts between academic conservatism and artistic experimentation.

Some of the most innovative Danish modernists—such as Vilhelm Hammershøi, Harald Giersing, and Theodor Philipsen—trained at the Academy but ultimately broke with its doctrines. Others, like Olaf Rude and Edvard Weie, joined or founded alternative schools and exhibitions, including the Den Frie Udstilling (The Free Exhibition), as a protest against academic gatekeeping.

Yet even as the Academy became a foil for rebellion, it remained central to the discourse. It was the institution artists reacted against—shaping their opposition just as surely as it had once shaped their instruction.

The Modern Academy: Transformation and Tension

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the Academy has continued to evolve, absorbing the shocks of abstraction, conceptual art, performance, and digital media. Its programs now encompass not only painting and sculpture but architecture, video, installation, and theory. Professors include practicing artists with diverse global backgrounds, and the pedagogy often leans toward critical inquiry rather than technique alone.

Yet this evolution hasn’t been without tension. Debates continue within the Danish art world about whether the Academy has lost its rigor or betrayed its roots. Others argue it is more relevant than ever, offering a space where tradition and innovation coexist in productive dialogue.

Global Reach and Continued Relevance

Today, the Royal Danish Academy remains a vital part of Copenhagen’s cultural ecosystem. It serves as an incubator for young talent, a research center, and a partner in international exchange. Its graduates continue to influence the broader art world, and its exhibitions draw scholars, critics, and collectors from around the globe.

Importantly, it remains a place where Danish identity is negotiated through art—just as it was in the 18th century. Whether through radical performance, minimalist design, or socially engaged installations, the Academy still holds a mirror to the nation.

Women Artists in 19th-Century Copenhagen

In the shadows of Copenhagen’s grand academies, salons, and studios, women were making art—often without the recognition or institutional support granted to their male counterparts. Yet their contributions were significant, and their perseverance reshaped the contours of Danish art history. The 19th century was a period of shifting roles and expanding possibilities for women in the arts, and while obstacles remained formidable, Copenhagen was home to a growing number of female artists who left their mark in ways both subtle and revolutionary.

Barriers to Entry: Exclusion from the Academy

For much of the 19th century, the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts did not admit women as full students. This exclusion meant that aspiring female artists had to pursue alternative paths to education—private instruction, informal mentorships, or training abroad. Even when women were permitted limited access (as auditors or in special “ladies’ classes”), they were typically barred from essential elements of the curriculum, such as life drawing from nude models—a cornerstone of academic training.

This institutional gatekeeping shaped the kinds of art women were able (or allowed) to make. Grand historical compositions, large-scale allegories, and figure studies were difficult to produce without access to models and commissions. Instead, women were often encouraged—or confined—to “feminine” genres: flower painting, miniature portraits, domestic interiors, and still lifes.

Yet within these genres, women artists carved out space for innovation and self-expression, transforming limitation into language.

Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann: The Outsider Within

One of the most fascinating figures of the era is Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (1819–1881), a German-born painter who became one of Denmark’s most prominent and controversial female artists. Trained in Düsseldorf, she arrived in Copenhagen with a distinctly cosmopolitan sensibility, eventually marrying the celebrated sculptor Jens Adolf Jerichau.

Her work defied the gendered expectations of Danish society. Jerichau-Baumann painted Orientalist scenes, mythological allegories, and eroticized female nudes—subjects typically reserved for male artists. Her An Egyptian Fellah Woman with Her Child (1872), for instance, blends anthropological curiosity with sensual idealization, reflecting both her travels and her negotiation with Orientalist tropes.

She was admired abroad—by Queen Victoria, no less—but often met with suspicion in Copenhagen, where her assertive careerism and subject matter clashed with bourgeois norms. In many ways, she was too bold for Denmark, too Danish for Europe, a woman whose art challenged not only aesthetic boundaries but the very gendered structure of the art world.

Domestic Interiors and the Quiet Radicalism of Everyday Life

Other women embraced the genres open to them, yet infused their work with emotional and psychological depth. Artists like Emilie Mundt, Marie Luplau, and Bertha Wegmann focused on intimate interiors, children, and female companionship, often depicting scenes of quiet introspection.

Bertha Wegmann (1847–1926), in particular, excelled in portraiture, becoming the first woman to hold a professorship at the Royal Academy—a remarkable achievement. Her portraits of women are notably unadorned, direct, and emotionally nuanced. She rejected the sentimental clichés often expected in depictions of women, offering instead a complex and unsentimental vision of female identity.

In her Portrait of a Young Girl (1895), for example, the sitter’s gaze is steady, her expression ambiguous—inviting the viewer not to consume her as a decorative object but to meet her as a subject with agency.

Women and the Studio Movement

Outside institutional structures, women created their own networks. The Studio Movement, which emerged in the late 19th century, offered communal workshops and exhibition spaces for female artists. These collectives allowed women to share resources, critique each other’s work, and gain visibility in a male-dominated art world.

Mundt and Luplau not only worked closely together but also advocated for women’s suffrage and education, linking artistic practice to broader feminist politics. Their paintings, often depicting working-class women or mother-child relationships, reflected a commitment to social realism and equality.

These women were not simply making art—they were making space for themselves and others, asserting a right to be seen, to create, and to define Danish culture on their own terms.

The Intersection of Class and Gender

It’s important to note that not all women had equal access to artistic careers. Many of the women who succeeded in 19th-century Copenhagen came from middle- or upper-class families who could afford private lessons or travel abroad. Working-class women, by contrast, were often relegated to artisanal crafts, textile work, or uncredited contributions to family studios.

However, even within these limits, women engaged in a rich culture of visual production—illustration, embroidery, ceramics, and photography—forms that are only recently being recognized as central to the history of Danish visual culture.

Recognition and Rediscovery

For much of the 20th century, the contributions of these women were neglected in mainstream art history. Museums rarely acquired their work, textbooks omitted their names, and their influence was underappreciated. But recent decades have seen a major reevaluation, led by curators, scholars, and feminist art historians.

Exhibitions such as “Women Artists in Denmark, 1800–1900” at the SMK have brought renewed attention to figures like Wegmann, Jerichau-Baumann, and Mundt. Their works are now seen not as peripheral but as integral to the story of Danish art—expanding our understanding of what it meant to be modern, to be Danish, and to be an artist.

Legacy in Contemporary Practice

Today, Copenhagen’s vibrant contemporary art scene includes many women who draw inspiration—consciously or not—from their 19th-century predecessors. Artists like Kirstine Roepstorff, Ursula Reuter Christiansen, and Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen continue to explore themes of gender, identity, and power, building on the foundations laid by the pioneering women of the past.

Their work, often interdisciplinary and politically engaged, underscores the enduring relevance of the questions 19th-century women artists posed: Who has the right to make art? Whose vision gets to shape the nation’s story?

Symbolism, Modernism, and the Turn of the Century (1880–1914)

As the 19th century drew to a close, Copenhagen found itself caught between worlds—between the lyrical naturalism of the Golden Age and the aesthetic turbulence that would define the 20th century. This transitional period, spanning roughly from the 1880s to the onset of World War I, was marked by artistic soul-searching. Danish artists, once content with quiet interiors and sun-dappled landscapes, began to explore mysticism, psychology, and abstraction. The result was a flowering of Symbolism, early Modernism, and new avant-garde movements that questioned not only style but the very purpose of art.

From Realism to the Inner World

The seeds of this shift were already visible in late Golden Age painting. Artists such as Vilhelm Hammershøi began to strip away narrative and detail, focusing instead on mood and silence. His spare, almost ghostly interiors—with their muted grays and faceless figures—hinted at the Symbolist impulse: to evoke not what is seen, but what is felt.

This emotional interiority marked a clear break from the sunlit clarity of Eckersberg and Købke. It was no longer enough to represent the external world faithfully; artists now sought to render dreams, memories, and subconscious desires. The turn-of-the-century art world was increasingly concerned with what lay beneath the surface—a trend that would reach a fever pitch with Expressionism and Surrealism.

Symbolism in Denmark: Nordic Mysticism and the Eternal

Danish Symbolism drew from international currents—particularly from France and Belgium—but it also carried a distinct Nordic sensibility. Artists like J.F. Willumsen, Ejnar Nielsen, and L.A. Ring developed a language rich with allegory, myth, and metaphysical longing.

- L.A. Ring (1854–1933) exemplifies this period’s complexity. Though rooted in realism, his paintings of rural life are often infused with eerie stillness or existential unease. Works like In the Garden Doorway (1897) seem simple, but their strange quietness and muted tones invite endless psychological interpretation.

- Ejnar Nielsen (1872–1956) painted scenes of illness, death, and spiritual struggle. His palette was often dark, his figures emaciated, their expressions haunted. These were images of the soul in crisis, reflective of a society grappling with modernity, industrialization, and spiritual doubt.

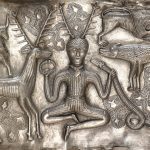

Symbolist artists often returned to pre-Christian mythology, folklore, and classical archetypes—not as escapism, but as a way to navigate a world that felt increasingly fragmented. Nature remained a central motif, but now it was charged with symbolic energy: a tree could suggest resurrection, a winding path the journey of the soul.

J.F. Willumsen: The Visionary Outsider

Perhaps the most radical and idiosyncratic figure of this period was Jens Ferdinand Willumsen (1863–1958), a painter, sculptor, and architect whose work defies easy categorization. Willumsen embraced color, distortion, and subjectivity in ways that scandalized traditionalists but foreshadowed Expressionism and even Modernist abstraction.

His painting A Mountain Climber (1904) is often seen as a manifesto of the modern self: heroic, solitary, striving. It eschews realism in favor of personal myth-making, positioning the artist not as a recorder of reality, but as a creator of new realities. Willumsen’s style was flamboyant and often polarizing, yet his influence can be seen in the freedom with which later Danish artists approached the canvas.

The Rise of Independent Exhibitions and Artistic Societies

As academic institutions struggled to accommodate these new sensibilities, many artists formed their own networks and exhibitions. The Den Frie Udstilling (The Free Exhibition), founded in 1891 by Willumsen, Nielsen, and others, was a response to the conservatism of the Royal Academy’s juried shows.

Modeled in part on the French Salon des Refusés, Den Frie gave space to experimental, controversial, and formally innovative works. Its existence signaled a democratization of artistic taste—a shift from state-sanctioned authority to a pluralistic, artist-led culture.

These alternative spaces also facilitated dialogue with international movements. Danish artists traveled to Paris, Berlin, and Rome, absorbing Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and early Cubism. While few fully embraced abstraction during this period, the door had been opened.

The Role of Literature and Theater

Visual art did not undergo this transformation alone. Copenhagen’s literary scene was likewise turning inward, grappling with themes of alienation, eroticism, and spiritual dread.

- Johannes Jørgensen, a leading Symbolist poet and writer, was closely aligned with the visual Symbolists. His mystical Catholicism and philosophical introspection echoed the themes explored in painting.

- In the theater, Henrik Ibsen’s psychological dramas, though Norwegian in origin, were staged frequently in Copenhagen, reflecting a pan-Scandinavian turn toward realism and psychological depth.

This intermingling of disciplines created a rich cross-pollination of ideas. Artists, writers, and composers gathered in cafés and salons, debating Nietzsche, Freud, and the role of the artist in a rapidly changing world.

Architecture and the Total Work of Art

Architecture also evolved during this period. The concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk—a “total work of art” combining architecture, design, and visual arts—gained traction. Architects like Martin Nyrop, designer of Copenhagen’s City Hall (1905), combined National Romantic styles with practical modernity.

The Arts and Crafts movement, though more muted in Denmark than in England, influenced furniture design, decorative arts, and typography. This fusion of aesthetics and utility would culminate in the mid-century Danish Modern movement—but its roots can be found here, in the eclectic, experimental energies of the fin-de-siècle.

A Culture on the Edge of Cataclysm

By 1914, Copenhagen was at a cultural crossroads. The energy of the preceding decades had produced a dazzling array of styles, movements, and manifestos—but the outbreak of World War I would alter the artistic landscape forever. While Denmark remained neutral, the war’s psychological and economic effects were deeply felt. The Symbolist yearning gave way to Modernist critique, and artists increasingly turned to abstraction, political engagement, and social commentary.

Yet the legacy of this era—the restless experimentation, the rejection of academic orthodoxy, the embrace of subjectivity—would shape Danish art for the next century.

Copenhagen Between the Wars: Avant-Garde and Experimentation

The interwar years in Copenhagen—spanning the aftermath of World War I through the outbreak of World War II—were marked by a sense of artistic restlessness and redefinition. This was a time when Danish artists actively questioned not only the traditions they had inherited but the very nature of what art should do. Influenced by the European avant-garde, many broke away from naturalism, symbolism, and romantic introspection in favor of formal innovation, political engagement, and radical play. It was an age of experimentation, where art splintered into new vocabularies: abstraction, Dada, Constructivism, Surrealism, and early social realism.

In Copenhagen, this meant both a continuation of cultural independence—Denmark had remained neutral in WWI—and a growing alignment with the modernist ferment of Berlin, Paris, and Moscow.

The Aftermath of War: Shifting Consciousness and Aesthetic Crisis

Although Denmark was not a combatant in World War I, the war cast a long cultural shadow. It shattered illusions about progress and rationality—ideals that had underpinned the Enlightenment and even aspects of the Symbolist era. The horrors of mechanized conflict, political upheaval, and the Spanish flu pandemic left a generation of European artists disillusioned, angry, and searching for new means of expression.

In Denmark, this crisis translated into a growing distrust of traditional aesthetics. Realism and sentimentality were seen by many younger artists as inadequate responses to a fragmented and rapidly changing world. The emerging generation wanted to deconstruct the past, not preserve it.

Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling and the Rise of Independent Platforms

While Den Frie Udstilling had broken academic ground in the late 19th century, the interwar period saw the emergence of new artist-led platforms, most notably Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling (The Artists’ Autumn Exhibition), founded in 1900 but taking on radical new life in the 1920s.

This open-call, juried exhibition became a breeding ground for avant-garde ideas, where new forms and provocations could be tested in front of both peers and the public. Artists who struggled to fit within the museum circuit or academic juries found space here for experimentation.

The tension between institution and independence, so characteristic of Danish art history, played out in dynamic ways during this period. These independent exhibitions didn’t just show new work—they challenged the entire structure of artistic validation.

Abstract Pioneers: Vilhelm Bjerke-Petersen and Constructivist Thinking

A key figure in interwar Danish modernism was Vilhelm Bjerke-Petersen (1909–1957), an artist, writer, and theorist who studied at the Bauhaus under Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. He brought back to Copenhagen the radical ideas of Constructivism, Surrealism, and automatism, injecting a dose of continental modernism into Denmark’s relatively restrained scene.

His works often combined geometric abstraction with mystical symbolism, and he became a crucial bridge between theory and practice. In 1934, Bjerke-Petersen published the influential treatise Surrealismen, which introduced Danish readers to the dreamlike, irrational worlds of André Breton, Max Ernst, and Salvador Dalí.

He also co-founded the Linien group in 1934—a collective of abstract and surrealist artists who challenged both conservative art and political complacency. Their exhibitions introduced Danish audiences to truly radical work and marked a significant turn toward art as psychological and political inquiry.

Linien and the Surrealist Turn

The Linien collective included artists like Ejler Bille, Richard Mortensen, and Sonja Ferlov Mancoba, all of whom explored abstraction, symbolism, and biomorphic form. Their art often merged the unconscious mind with political engagement—reflecting a world drifting toward another catastrophic conflict.

- Sonja Ferlov Mancoba (1911–1984), in particular, stands out as one of Denmark’s most original sculptors. Deeply influenced by non-Western art, her work combined modernist abstraction with organic forms, often suggesting a search for universal spiritual truths in a fractured world.

- Ejler Bille experimented with collage, texture, and chance, often producing work that felt improvisational, almost jazz-like in rhythm and repetition.

While Surrealism in Denmark was never as overtly political or sexually charged as in France or Spain, its core tenets—automatism, irrationality, dream logic, and archetype—took on uniquely Scandinavian resonances. It became a way of navigating the instability of the age.

Cultural Crosscurrents: Danish Artists Abroad

During this period, Copenhagen-based artists were increasingly mobile. They traveled to Paris, Berlin, Munich, and Prague, where they encountered Cubism, Dada, and emerging abstraction. These international dialogues influenced their techniques and expanded their conceptual horizons.

But these trips were not simply pilgrimages to artistic meccas. Many Danish artists viewed the larger European scene with a blend of admiration and skepticism, seeking to absorb without abandoning their own cultural context. As a result, interwar Danish modernism often maintained a certain modesty—a commitment to clarity, balance, and humanism even within experimental forms.

Social Engagement and Critical Realism

While abstraction and Surrealism captivated the avant-garde, other artists in Copenhagen turned to social realism and critical figuration to document the struggles of the working class, the unemployed, and the alienated. Inspired by leftist politics and the rise of labor movements, these artists believed art should serve the public—not just the elite.

Figures like Poul Henningsen, though more known for design and criticism, championed this politically charged approach to culture. He believed that art should speak to real people and real problems, not just adorn galleries.

This tension—between formal innovation and social commitment—defined much of the era’s visual output.

The Shadow of War

As the 1930s progressed and fascism rose across Europe, many Danish artists grew increasingly politicized. Art became a mode of resistance, both stylistically and ideologically. While Denmark remained democratic, the threat of war and authoritarianism was palpable.

By the time Germany invaded in 1940, many of the seeds of resistance—visual, intellectual, and emotional—had already been planted during this restless interwar period.

Art and Resistance During the Nazi Occupation (1940–1945)

When Nazi Germany occupied Denmark on April 9, 1940, the city of Copenhagen—its art, its culture, its soul—was thrust into an uneasy dance between survival and resistance. Unlike many other occupied nations, Denmark was allowed to retain nominal autonomy under the German “model protectorate” system. But this superficial normalcy masked deep political tensions and a culture of quiet defiance. In this climate, art became both a coded language and a weapon, a way to preserve dignity, affirm identity, and resist erasure without overt provocation.

The occupation years produced a body of work that was neither propagandistic nor escapist. Instead, artists used metaphor, abstraction, irony, and symbolism to communicate dissent—and to envision a freer future.

The Cultural Strategy of Subtle Defiance

From the outset, Danish artists were confronted with a dilemma: how to create in a time of oppression without becoming complicit. Censorship was real but relatively soft—there were no state-run propaganda ministries forcing artists to comply, yet overt political statements could trigger bans or worse.

The solution was often indirection. Artists turned to allegory, myth, and abstraction—not as formal choices, but as survival strategies. A painting of a weather-beaten oak might represent the resilience of the Danish people. A distorted figure might hint at psychological trauma or loss. The very act of continuing to create was itself a gesture of endurance.

The Høst Group and Symbolic Resistance

One of the key collectives active during this time was the Høst Group, founded in 1934 but gaining urgency and visibility during the war. Artists like Ejler Bille, Richard Mortensen, and Asger Jorn explored abstract and surrealist forms to critique a world unraveling.

- Asger Jorn, who would later co-found the CoBrA movement, used aggressive brushwork, distorted figures, and primal color to express the chaos and absurdity of the era. His early works during the occupation hinted at suppressed violence, existential dread, and the fragility of civilization.

The Høst Group refused the clarity and control favored by authoritarian regimes. Their art was often raw, fragmentary, and open-ended—a direct challenge to fascist ideals of order, purity, and conformity.

Asger Jorn and the Seeds of Postwar Radicalism

Jorn in particular stands out as a bridge between wartime resistance and postwar artistic revolution. During the occupation, he was influenced by Marxist theory, existential philosophy, and the work of Kafka. Though not overtly political in iconography, his art during this time seethes with the tension of suppressed resistance.

One can read his gestural style—abrupt, violent, unresolved—as a kind of visual scream. After the war, Jorn would become one of Denmark’s most internationally influential artists, but his roots lay in the psychological and political urgency of these dark years.

Underground Press and the Role of Graphic Art

While fine art turned to metaphor, graphic artists and illustrators played a more direct role in resistance. Underground newspapers—vital to the Danish resistance movement—used political cartoons, clandestine posters, and satirical illustrations to mock Nazi authorities, rally support, and spread coded messages.

Artists such as Poul Henningsen and Herluf Bidstrup produced biting visual commentary that was often smuggled across the country. These works were designed not for galleries, but for streets, cafés, and secret gatherings—art as samizdat, created for immediacy and impact.

Theater and Music as Clandestine Culture

Resistance wasn’t limited to visual artists. The Danish theater scene also adapted to the constraints of occupation. Playwrights turned to historical drama and allegory, staging stories of ancient tyranny, moral courage, and collective memory that subtly echoed contemporary anxieties.

Musicians, too, resisted through coded performances—playing banned works by Jewish composers like Mendelssohn or Shostakovich’s “subversive” symphonies. Public concerts often took on an atmosphere of solemn protest, especially when paired with poetry or readings that hinted at national perseverance.

Public Murals and Hidden Messages

In public space, resistance was often encoded in subtle acts of visual protest. Artists painted murals or displayed works in galleries that, on the surface, appeared apolitical but contained veiled references to occupation and suffering.

A horse with blinders might suggest a populace refusing to see. A crumbling wall might symbolize a collapsing regime. In some cases, even color schemes—reds, whites, and blues—were used to evoke Danish patriotism under the radar of censors.

This tactic of visual ambiguity became a hallmark of wartime expression: artworks designed to be read in multiple ways, offering safety to the creator while speaking volumes to the viewer.

Jewish Artists and the Art of Survival

Denmark is rightly remembered for its collective effort to save its Jewish citizens in 1943, when over 7,000 were ferried to safety in Sweden. Many Jewish artists and intellectuals were part of this exodus.

Some, like painter and writer Victor Haïm, resumed their work in exile, using art to process trauma and displacement. Others never returned. The absence of these voices became another layer in Denmark’s cultural loss—a silence that lingered even after liberation.

Post-Liberation Reflection

When Denmark was liberated in May 1945, there was no sudden artistic renaissance. The trauma of the occupation took years to process, and many artists remained emotionally and politically scarred. But in retrospect, the work produced during the occupation has been recognized not only for its courage, but for its depth—a kind of internalized heroism that privileged resilience over rhetoric, nuance over noise.

The war years reminded Danish artists—and their audiences—that art does not need to shout to resist. Sometimes, it is the quietest images that endure the longest.

Postwar Rebuilding and the Rise of Danish Modern Design

In the wake of Nazi occupation and the traumas of World War II, Copenhagen—like much of Europe—stood at a cultural and material crossroads. The city was physically intact compared to the bombed-out ruins of Berlin or London, but its identity needed rebuilding. Into this space of renewal came a vision both forward-looking and deeply rooted in Danish values: Danish Modern Design.

While not confined to Copenhagen alone, the movement found a fertile home in the capital’s studios, showrooms, workshops, and schools. In the decades following the war, Copenhagen emerged as a global center for design and functionalist aesthetics, bridging fine art, craft, architecture, and industrial production. And crucially, this was not a turn away from art—it was an expansion of it. In postwar Denmark, to design a chair was to express an ideal. To craft a teapot was to participate in a cultural philosophy.

From Scarcity to Simplicity: The Social Roots of Danish Design

The postwar years were shaped by austerity, social democracy, and the practical demands of reconstruction. Danish artists and designers responded not with grand gestures or monumental architecture, but with human-scale innovation.

This ethos was captured in the Danish term “hygge”, often mistranslated as coziness but more accurately reflecting a desire for comfort, order, and harmony in daily life. It was also deeply democratic: good design should be available to everyone, not just the elite.

Copenhagen became the epicenter of this vision, as architects, furniture designers, and craftspeople sought to balance beauty with utility. The idea was simple: if we build better surroundings, we build a better society.

Arne Jacobsen and the Total Design Aesthetic

The towering figure of this movement was Arne Jacobsen (1902–1971), an architect and designer whose work epitomized Danish Modern principles. A Copenhagen native, Jacobsen believed in the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. He didn’t just design buildings—he designed the chairs, lighting, cutlery, and textiles to go inside them.

His most famous works—the Egg Chair (1958), Swan Chair, and the Series 7 Chair—are icons of 20th-century design: minimal, elegant, and ergonomically refined. These objects became international exports of Danish taste, found in airports, boardrooms, and homes around the world.

Yet Jacobsen’s vision wasn’t merely aesthetic. His 1956 SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen was a manifesto of modern living, where form and function were inseparable. The hotel’s interiors, from the spiral staircase to the silverware, embodied a belief in design as a social ideal—streamlined, accessible, and quietly luxurious.

The Furniture Revolution: Craft Meets Machine

Copenhagen’s design culture thrived in part because it retained strong ties to traditional craftsmanship. Designers like Hans J. Wegner, Finn Juhl, and Børge Mogensen collaborated closely with cabinetmakers and artisans to produce work that combined modernist form with natural materials—especially wood.

Wegner’s iconic Wishbone Chair (1949) is a case in point. Its minimalist silhouette and handwoven seat are both sculptural and functional, embodying the very spirit of Danish design: to elevate the ordinary object into something timeless.

These designers were not operating in isolation. Copenhagen was home to exhibitions, showrooms, and institutions—such as the Danish Design Museum (Designmuseum Danmark)—that promoted, curated, and preserved this aesthetic legacy. Their output blurred the line between fine art and utility, emphasizing beauty in even the most mundane tools of life.

Modern Architecture in Postwar Copenhagen

Alongside the furniture revolution, architecture in postwar Copenhagen embraced modernist simplicity. Influenced by Le Corbusier and Bauhaus rationalism, Danish architects favored clean lines, functional layouts, and open spaces.

Key projects included:

- Bellahøjhusene: Denmark’s first high-rise housing estate, built in the 1950s, combining modern planning with a Scandinavian emphasis on light and green space.

- The Gladsaxe Town Hall by Arne Jacobsen: an example of civic architecture that merges public functionality with modern aesthetics.

These buildings weren’t flashy—they were meant to be lived in, to make modern life more humane, efficient, and beautiful.

Women in the Workshop: A Quiet Revolution

Though mid-century design history often centers on male figures, Copenhagen was also home to a number of influential women designers. Grete Jalk, for instance, designed modular furniture and minimalist forms that challenged gendered assumptions about domesticity and labor.

Women were also active in textile design, ceramics, and silverwork, with figures like Karen Clemmensen, Nanna Ditzel, and Gertrud Vasegaard shaping everything from wallpaper patterns to tableware. Their work, though sometimes relegated to “applied arts,” was no less critical to the visual and material culture of postwar Denmark.

Design as Diplomacy: Copenhagen on the World Stage

In the 1950s and ’60s, Danish design became an export commodity and a soft power strategy. Embassies, international fairs, and luxury retailers all showcased Copenhagen’s design ethos as a symbol of Nordic modernity—rational, ethical, and stylish.

The design boom became part of Denmark’s global identity, setting it apart from the chaos and excess of other postwar cultures. Copenhagen was portrayed as a laboratory of livable modernism, where good taste was not a privilege but a civic duty.

Legacy and Reassessment

Today, the principles of Danish Modern still shape everything from IKEA’s mass-market minimalism to Silicon Valley’s sleek tech aesthetics. But in Copenhagen, there is also a renewed interest in the social mission of postwar design—not just its forms, but its values.

Younger artists and architects are reexamining the mid-century legacy through the lens of sustainability, affordability, and inclusivity. New design hubs—like BLOX and the Danish Architecture Center—build on the tradition, asking how design can respond to climate change, urbanization, and inequality.

Contemporary Art in Copenhagen: Superflex, Elmgreen & Dragset, and Beyond

Copenhagen today is a city buzzing with creativity, where art spills beyond gallery walls into the streets, harbor fronts, and even power plants. Its contemporary art scene—experimental, socially engaged, and globally connected—carries forward the country’s legacy of aesthetic precision while pushing boundaries in bold, provocative ways.

The city’s artists are no longer concerned merely with form or national identity. They grapple with climate change, capitalism, migration, gentrification, and surveillance—topics that define the global present. In doing so, they have turned Copenhagen into one of Northern Europe’s most innovative centers for contemporary art, rooted in Scandinavian values of collectivism, ecology, and critical reflection.

Superflex: Art as Social Infrastructure

No discussion of contemporary Copenhagen art is complete without Superflex—the artist collective founded in 1993 by Jakob Fenger, Rasmus Nielsen, and Bjørnstjerne Christiansen. Based in Copenhagen but active worldwide, Superflex redefines what art can be: not an object or spectacle, but a tool for social engagement.

Their projects are often large-scale, interdisciplinary, and conceptual. A few notable examples:

- “Superkilen” (2012): A public park in Nørrebro designed in collaboration with BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) and Topotek1. This urban space incorporates objects and cultural symbols from over 60 nationalities, reflecting the area’s diversity while challenging ideas of public identity and ownership.

- “Power Toilets / VIP” (2010): A replica of the exclusive restroom at the UN Security Council, installed in a public park. The piece questions institutional privilege, access, and the absurdity of bureaucratic power.

- “Flooded McDonald’s” (2009): A video work in which a life-size McDonald’s restaurant is slowly submerged in water—a haunting allegory for climate change, globalization, and consumerism’s collapse.

Superflex’s work is anti-elitist and often deeply playful, yet always underpinned by serious social commentary. Their studio is less a gallery space than a think tank, where art, activism, architecture, and economics intersect.

Elmgreen & Dragset: Queer Space, Institutional Critique, and Performance

Another international power duo based in Copenhagen (and Berlin) is Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, whose sculptural installations and performances explore themes of identity, public space, and the contradictions of contemporary life.

Their practice thrives on displacement—placing the intimate in public, or the public in intimate contexts:

- “Prada Marfa” (2005): A permanent installation resembling a luxury boutique in the middle of a Texas desert, commenting on consumerism, luxury culture, and urban alienation.

- “Powerless Structures” series: Bronze sculptures of children in ordinary moments, installed in monumental settings—challenging heroic traditions in public sculpture and reframing vulnerability as strength.

- At Copenhagen’s Statens Museum for Kunst, their work has often played with institutional space, turning gallery halls into domestic scenes or unsettling viewers with subtle disruptions in museum logic.

Their work, like Superflex’s, is theatrical, critical, and sharply ironic, inviting viewers not just to look, but to inhabit a conceptual space where norms are upended and meaning is fluid.

Art Beyond the White Cube: Public, Participatory, and Political

Contemporary art in Copenhagen has increasingly spilled into public space, shaped by government support for creative placemaking and the city’s tradition of accessible culture. Projects commissioned by Københavns Kommune, Copenhagen Contemporary (CC), and Overgaden Institute of Contemporary Art have transformed old industrial spaces into living galleries.

One striking example is Refshaleøen, a former shipyard turned cultural zone, now home to Copenhagen Contemporary—an exhibition hall dedicated to large-scale, immersive installations. Artists like Tomas Saraceno, Lea Porsager, and Ragnar Kjartansson have all shown there, creating works that blend science, philosophy, and spectacle.

Another important venue is Kunsthal Charlottenborg, which serves as a barometer of experimental trends, regularly hosting works that blur media boundaries—video, VR, performance, AI-generated art. It’s also the exhibition space for graduates of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, giving voice to emerging talents.

Ecology and Climate: Art in the Anthropocene

Copenhagen’s contemporary art scene is acutely aware of its environmental context. Situated in a low-lying coastal zone, Denmark is on the frontlines of climate change—and artists are responding with urgency and innovation.

- Tue Greenfort integrates ecology, biology, and technology, creating installations that function as living systems—biotopes, algae farms, compost machines—asking us to rethink the boundaries between nature and culture.

- Marianne Jørgensen’s “Pink M.24 Chaffee Tank” (2006)—a real tank knit in pink wool—protested Denmark’s involvement in the Iraq War, fusing craft and critique in a feminist, pacifist gesture.

- Artists like Eva Koch and Kirstine Roepstorff continue to address climate anxiety and collective trauma through video, sculpture, and ritual-based performance.

Digital Frontiers and New Media

Younger artists in Copenhagen are increasingly working with technology, code, and data, exploring how digital life reshapes identity, perception, and memory. There’s a fluidity now between visual art, sound, and design—drawing from Denmark’s deep design heritage but pushing it into post-internet territories.

VR installations, generative art, and interactive pieces have found homes at institutions like ARKEN Museum of Modern Art and The National Gallery (SMK), both of which have expanded their collections to reflect these new practices.

Global Voices in a Local Scene

Contemporary Copenhagen is pluralistic and multilingual. Artists of immigrant background, queer identity, and diasporic experience are reshaping the narrative of Danish art. The city’s contemporary scene is no longer defined by a unified aesthetic but by friction, hybridity, and dialogue.

Artists like Jeannette Ehlers, whose Afro-Caribbean-Danish identity informs her work on colonial history and memory, or Mohamed Bourouissa, whose collaborations touch on urban marginality and surveillance, exemplify a city that is as global as it is grounded.

Museums and Public Art: Copenhagen as a Living Gallery

Copenhagen is more than the sum of its art institutions—it is, in many ways, a city-wide exhibition. Here, centuries of artistic achievement are not locked away but dispersed across streets, parks, waterfronts, and public squares. The Danish capital is a city that takes cultural access seriously, guided by the belief that art should be part of everyday life, not just a weekend destination. This ethos has shaped the city’s extraordinary network of museums, galleries, and public installations, making Copenhagen one of the most vibrant and democratic art capitals in Europe.

Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK): The National Gallery

The beating heart of Denmark’s public art collection is the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), located in central Copenhagen beside the King’s Garden. Founded in 1896, the museum bridges the classical and the contemporary, housing over 260,000 works that span from the Renaissance to the 21st century.

The SMK’s greatest strength is its Danish Golden Age collection, with works by Eckersberg, Købke, and Hammershøi forming the core of its narrative. But it also boasts impressive holdings in European Old Masters, including Rembrandt and Rubens, and a growing reputation for modern and contemporary art, with an emphasis on socially engaged and digital practices.

The museum actively collaborates with living artists, hosts residencies, and produces installations that respond to current social and political issues. It’s not a mausoleum of masterpieces—it’s a living platform for artistic dialogue.

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek: Art in a Temple of Beauty

Founded in 1897 by beer magnate and philanthropist Carl Jacobsen, the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek is a stunning blend of private passion and public mission. The museum houses Jacobsen’s vast collection of classical sculpture, French Impressionism, and 19th-century Danish art, displayed in a building that feels like a cross between a winter garden and a Mediterranean villa.

The Glyptotek is particularly known for:

- Its Rodin collection, one of the largest outside France

- Works by Degas, Monet, Cézanne, and Gauguin

- Architectural harmony, with mosaic floors, palm courts, and glass domes

It’s a museum of sensual immersion, where the lines between architecture, sculpture, and atmosphere dissolve.

ARKEN Museum of Modern Art: By the Sea, Beyond the Frame

South of Copenhagen, in Ishøj, lies the ARKEN Museum, a bold, ship-shaped structure emerging from the dunes. Opened in 1996, ARKEN specializes in contemporary art—often large-scale, immersive, and experimental.

The museum has hosted international stars like Damien Hirst and Olafur Eliasson, while maintaining a strong focus on Nordic artists. Its exhibitions frequently tackle climate change, identity, and media culture, and its seaside location reinforces the connection between nature and culture.

ARKEN also engages deeply with community art, accessibility, and multicultural programming, reflecting the demographic shifts of the broader Copenhagen area.

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art: A Day Trip into the Sublime

Though technically outside Copenhagen (an easy train ride away in Humlebæk), the Louisiana Museum is so essential to Denmark’s cultural landscape that it belongs in any Copenhagen-centered discussion.

Perched above the Øresund Strait, Louisiana seamlessly integrates landscape, architecture, and art, with its sculpture garden and panoramic views creating an atmosphere of contemplative wonder. The collection includes:

- International postwar masters (Giacometti, Rauschenberg, Warhol)

- A robust program of global contemporary exhibitions

- The Louisiana Channel and Literature festival, expanding its reach into media and critical discourse

Louisiana is not just a museum—it’s an art experience, one that typifies the Danish talent for blending intellectual rigor with aesthetic pleasure.

Copenhagen Contemporary: Art at the Industrial Edge

In a repurposed welding hall on Refshaleøen, Copenhagen Contemporary (CC) has become a new hub for large-scale installations, light art, and interdisciplinary experimentation. Opened in 2016, CC represents the city’s latest move toward making art massive, immersive, and socially resonant.

With its industrial backdrop and cutting-edge exhibitions, CC positions Copenhagen at the forefront of experiential art—welcoming works that demand to be walked through, touched, or listened to rather than simply viewed.

Public Art: Sculptures, Murals, and Urban Interventions

Beyond the museum walls, Copenhagen is filled with public art that redefines civic space. From the iconic Little Mermaid statue on the Langelinie promenade to the politically charged graffiti of Christiania, the city invites a constant visual dialogue.

Key examples include:

- Elmgreen & Dragset’s “Han” in Helsingør: a polished, male version of the Little Mermaid, questioning gender and national symbols.

- Superkilen Park in Nørrebro: a vibrant social sculpture that incorporates everyday objects from over 60 countries.

- Temporary installations in Kongens Nytorv and along the harborfront that engage with climate change, protest, and historical memory.

In Copenhagen, art is not an add-on. It is embedded into how the city sees itself—as a living gallery, where the past informs the present, and the present keeps rewriting the story.