Before a single stone was laid, Canberra was a concept—an idea drawn in ink, layered with lakes, axes, and green corridors. Unlike most national capitals, it was not shaped by centuries of organic growth but by a deliberate act of imagination. The founding of Canberra in the early 20th century offered an unusual opportunity: to design a city not only for governance, but for symbolic clarity—a purpose-built centre for national meaning. And with that ambition came the question of what visual language should define the art, architecture, and public space of a new Australia.

Griffin’s vision: geometry, landscape, and aspiration

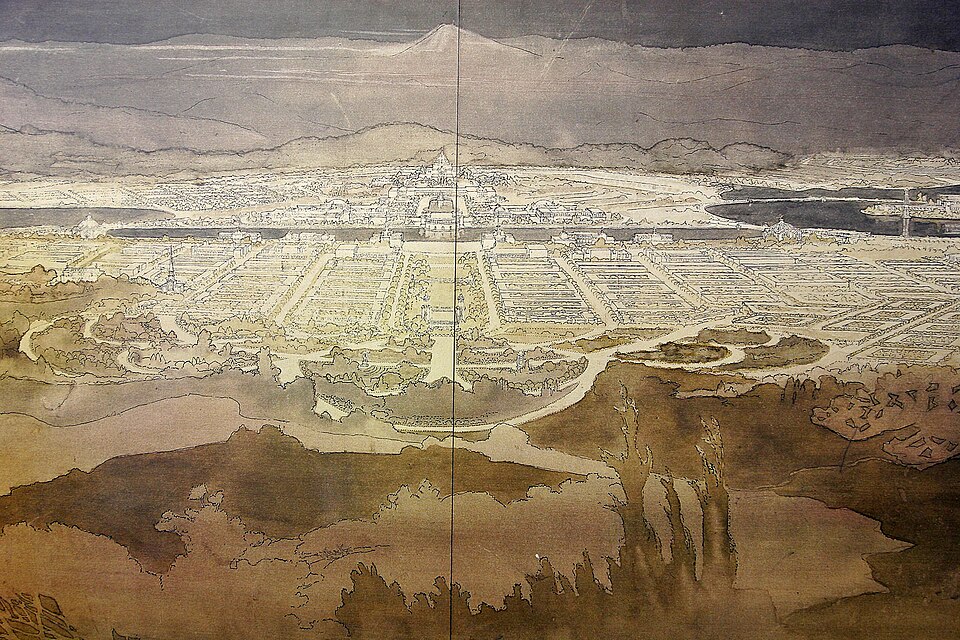

In 1911, the Australian government launched an international design competition to create a new capital city. The following year, the American architect Walter Burley Griffin, with substantial input from his wife and collaborator Marion Mahony Griffin, submitted a plan unlike any other. It was an elegantly interlocked geometry of radiating avenues, formal axes, and natural landforms. The Griffins conceived of the city not merely as a functional space but as a symbolic artefact—almost a kind of landscape artwork—where the built environment would harmonise with its setting and project a sense of national identity.

Marion Mahony Griffin’s watercolor renderings of the design were instrumental in swaying the judges. They presented Canberra not as a sterile diagram but as a sweeping utopian vision. Her drawings, now housed in the National Archives of Australia, depict the city as a living organism nested into the undulating terrain, punctuated by monumental focal points and softened by carefully planned vegetation. The plan included a “land axis” aligning with Mount Ainslie and a “water axis” anchored by an artificial lake—later to become Lake Burley Griffin.

The plan triumphed in 1912, but implementation stalled for years amid political shifts, financial constraints, and World War I. The Griffins’ authority over the project was eroded by bureaucratic infighting, and Walter Burley Griffin eventually resigned in frustration in 1920. Yet the conceptual framework he laid down continued to exert a long gravitational pull over the city’s development. In 1924, the Griffin Plan was officially gazetted, giving legal protection to its underlying structure. Even today, that plan undergirds Canberra’s layout—its concentric rings, axial alignments, and wide ceremonial avenues.

Canberra as a stage for national art

What kind of art emerges in a city where the entire urban plan is already an artwork? From the outset, Canberra was envisioned as a symbolic stage—where every building, sculpture, and sightline might contribute to the performance of national identity. Unlike Sydney or Melbourne, which evolved through mercantile and colonial competition, Canberra was an abstraction: a city of ideals before it became a city of people. That fact shaped the character of its cultural development.

Early discussions about the capital’s visual identity tended to revolve around formality and order. Public art was not seen as spontaneous expression but as monumental declaration. Government buildings were designed with hierarchy in mind—architecture as authority. This did not leave much room for bohemian ferment or outsider voices. Art in Canberra, at least in the early decades, was primarily institutional: part of the machinery of national symbolism.

Yet this formality had its advantages. It created a fertile space for commissions, curated collections, and architectural ambitions. While other cities saw culture emerge from artist-run spaces or avant-garde salons, Canberra embedded culture into its infrastructure. When Lake Burley Griffin was finally completed in 1964—realising the Griffins’ long-delayed water axis—it became not just a recreational site but a sculptural and spatial anchor. Around it would rise the major cultural institutions: the National Library (1968), the High Court (1980), and the National Gallery of Australia (1982), among others.

Aesthetic bureaucracy: the art of government taste

In Canberra, taste was often legislated. The city’s cultural tone was shaped by public service committees, acquisition boards, and interdepartmental negotiations. Even the placement of a sculpture required approval by bodies such as the National Capital Development Commission or the more recent National Capital Authority. As a result, Canberra became a case study in how bureaucracy can sculpt the visual world—not necessarily as an enemy of creativity, but as its peculiar patron.

Three phenomena emerged from this bureaucratised aesthetic:

- A cautious modernism, where international trends like Brutalism or Minimalism were adopted but tempered by civic restraint.

- A reliance on “safe innovation,” where art was encouraged to be contemporary but not disruptive—resulting in works that often prized formal ingenuity over raw provocation.

- A preference for monumental scale, especially in public commissions—art that could be seen from afar and read in alignment with the city’s axial geometries.

This environment shaped the careers of artists whose work navigated institutional approval. While Canberra did eventually produce more experimental and grassroots scenes, its foundational aesthetic was one of order, clarity, and civic symbolism.

An unresolved ideal

The paradox of Canberra lies in its perfection. Designed for harmony, it sometimes feels antiseptic. Its axial alignments and rational grids, while elegant, can lack the generative friction of denser urban environments. For many artists, this has posed a challenge: how to make meaningful, urgent work in a place conceived as a diagram of national order.

Yet that very tension—the pull between abstraction and reality, symbol and sensation—has seeded some of the city’s most interesting artistic responses. Artists have engaged the city not just as backdrop but as question: What does it mean to create art in a place designed for government? Can aesthetic expression emerge from a civic blueprint? Is national culture a performance or a practice?

These questions would reverberate across the decades, shaping the character of Canberra’s institutions, the work they exhibited, and the artists they supported. The city that began as a drawing has never stopped being a site of aesthetic negotiation.

Chapter 2: Custodians of Country — Aboriginal Art and Ngunnawal Presence

A land already known, already marked

Long before Canberra was selected, surveyed, or sketched into a capital, it was country: a lived, known, and culturally inscribed landscape. The plains, ridges, and waterways of what is now the Australian Capital Territory were not empty, not neutral, and not awaiting design. They belonged to the Ngunnawal people—custodians of a region rich with stories, pathways, ceremony, and aesthetic traditions. In the layered ground beneath Lake Burley Griffin, and in the ochres of Gubur Dhaura, lie traces of a continuous culture that predates the capital by thousands of years. The art history of Canberra cannot begin with Federation; it begins with Country.

Gubur Dhaura: ochre, trade, and deep time

In the suburb of Franklin, a low hill rises modestly above the surrounding development. This is Gubur Dhaura—literally “red ochre ground”—a significant site of Aboriginal ochre extraction. For generations, Ngunnawal people and other local nations such as the Ngambri, Ngarigo, and Wiradjuri came here to quarry and use the vibrant red, yellow, and white pigments from the exposed ridges. These were not only artistic materials but ceremonial ones: ochre for body painting, for mortuary rites, for trade, and for maintaining relationships across language groups.

Today, Gubur Dhaura is a heritage park, bordered by modern streets and housing estates. But the ground is still visibly stained with red earth, and interpretive signage offers glimpses into the artistic and ritual significance of the site. It is a reminder that long before “art” was institutionalised into galleries and curricula, it was embedded into the terrain—extracted, carried, and applied in acts of identity, connection, and meaning.

That ochre travelled. It moved in skin bags and memory lines across hundreds of kilometres, as part of a network of exchange that was at once economic and cultural. To speak of Ngunnawal art is to speak not only of this country but of the relationships it maintained beyond itself.

Ngunnawal presence in a bureaucratic capital

The creation of Canberra as a national capital in the early 20th century was predicated on a myth of emptiness. The Griffins designed for beauty and symbolism, but their canvas was imagined as blank. Aboriginal presence was not erased so much as rendered invisible—filtered out by the language of planning and progress. For decades, Ngunnawal people were politically and artistically marginal to the institutions that rose on their land.

Yet presence persisted. Families stayed. Cultural practices endured, often out of public view. And over time, Ngunnawal artists, educators, and activists began to assert both visibility and belonging in the increasingly formal cultural life of the city. What had been sidelined began to re-enter—not as decoration, but as correction.

This shift is now visible in public and institutional spaces. At the University of Canberra, the Ngunnawal Centre recently unveiled a series of painted poles by student and artist Ken Williams. The work draws on motifs of community, learning, and connection to land. Its installation at the entrance to a campus building is both literal and symbolic—a visual assertion that Aboriginal knowledge systems stand at the threshold of contemporary knowledge production.

Visual Yarns: contemporary practice rooted in Country

Leah Brideson is a Canberra-based artist whose work offers a vivid synthesis of tradition and innovation. A descendant of the Kamilaroi people, she lives and works on Ngunnawal country, and her practice is deeply shaped by that local terrain. Brideson refers to her works as “Visual Yarns”—a phrase that evokes storytelling, texture, and continuity. Her pieces often use dot work, circular forms, and aerial perspectives to reflect land memory, seasonal change, and lived connection.

Brideson’s paintings are not literal depictions of places. Rather, they act as maps of experience—emotional, spiritual, and environmental. They are works made for 21st-century audiences but rooted in a worldview where art and land are inseparable. Her palette—often soft earth tones interspersed with bursts of colour—draws directly from the ACT’s geology, flora, and atmospheric shifts. In this way, she reclaims landscape painting from colonial optics and repositions it as an Indigenous practice of care, record, and reassertion.

What distinguishes artists like Brideson is not only their personal idiom but their deliberate grounding in place. In a city whose visual identity has been largely sculpted by bureaucracy, abstraction, and monumental modernism, their work offers a counter-narrative: one of quiet, patterned intimacy with land.

Inside the national institutions

One of the great paradoxes of Canberra is that the most significant collection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art is held in a federal institution built on Indigenous land. The National Gallery of Australia, opened in 1982, houses over 7,500 Indigenous works—arguably the most comprehensive such collection in the world. Its holdings include bark paintings from Arnhem Land, dot paintings from the Central Desert, fibre works, carvings, and major contemporary commissions.

Yet until the 1990s, Indigenous art was often displayed in the NGA’s ethnographic or decorative arts contexts—segregated from the Australian “mainstream.” It took sustained curatorial advocacy, most notably from figures like Margo Neale and Wally Caruana, to reposition Indigenous work as contemporary, conceptual, and sovereign.

The gallery’s 2010 expansion of its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander galleries marked a turning point. With architectural elements that evoke earth, shelter, and country, the wing was designed to accommodate large-scale works as well as intimate ceremonial pieces. It placed Indigenous art at the literal and symbolic centre of the national visual narrative.

Still, tensions remain. Questions of provenance, ownership, and interpretive framing continue to shape how such works are acquired and exhibited. And while the presence of these works in the NGA is a form of recognition, it does not resolve the deeper structural imbalances in cultural authority or representation.

Endurance, not inclusion

Too often, Aboriginal art in Canberra has been treated as something to be “included”—an additive gesture within an already-formed narrative. But this framing misunderstands both the depth and the priority of Indigenous cultural life in the region. The Ngunnawal story is not a subplot. It is the ground on which all else stands.

What emerges from the art of Gubur Dhaura, from the patterns of Leah Brideson, from the poles at the Ngunnawal Centre and the holdings of the NGA, is not a tokenistic presence but an enduring one. One that predates planning, outlasts policy, and reshapes the narrative of national art from its margins inward.

The capital has begun, belatedly, to reckon with this. But for Ngunnawal artists and their peers, the work is not to be included—it is to be recognised as originary. Their art does not ask to be seen. It insists that we understand where we are standing.

Chapter 3: The Federal Dream — Nation-Building Through Cultural Institutions

An art made for a nation, not a city

In most cities, cultural institutions grow out of civic ambition or private patronage. But in Canberra, they were written into the very function of the city—federal by nature, symbolic by design. The task of creating a national capital was never just about housing politicians. It was about projecting a cultural narrative through buildings, collections, and artworks that would articulate the identity of a federated Australia. From the 1960s onward, a series of grand institutional projects transformed Canberra from a government outpost into the aesthetic nerve centre of the country.

The National Gallery of Australia: origins of a monument

The most potent example of this cultural ambition was the creation of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA). Though it officially opened its doors in October 1982, the process of building the institution began nearly two decades earlier. Planning commenced under the Holt government, accelerated during the Whitlam era, and culminated in a Brutalist concrete complex designed by architect Colin Madigan, sitting dramatically near Lake Burley Griffin.

The NGA was always more than a museum. It was an assertion: that Australia, though young in federal terms, possessed both the authority and the vision to assemble a “national” collection worthy of international standing. In doing so, it entered a complex arena of cultural politics—what kinds of art would be included, which histories privileged, whose voice the gallery would speak with.

Nothing captured this tension more publicly than the acquisition of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles in 1973. Purchased for $1.3 million by then-director James Mollison, with the backing of the Whitlam government, the abstract expressionist canvas sparked outrage and fascination in equal measure. Critics decried the expense, the foreignness, and the seemingly chaotic style of the work. Yet the purchase marked a pivotal moment: a declaration that Australia’s national gallery would not be parochial. It would engage with global modernism, make bold decisions, and provoke debate.

Building symbolism in concrete and stone

The NGA did not rise in isolation. Its establishment coincided with a broader reimagining of Canberra’s cultural landscape, largely orchestrated by the National Capital Development Commission (NCDC), the agency tasked with translating Griffin’s abstract geometry into civic infrastructure. The NCDC, especially active from the 1950s to the 1980s, viewed art institutions as essential components of Canberra’s identity—not as amenities, but as symbols of nationhood.

This vision led to the development of what is now known as the Parliamentary Triangle—a zone bordered by Kings Avenue, Commonwealth Avenue, and the southern bank of Lake Burley Griffin. Within this area, the NGA was joined by the High Court of Australia, the National Library, and the National Portrait Gallery, creating a tight cluster of monumental architecture and curated culture.

Each building in this precinct was not only a vessel for art or knowledge but a sculptural statement in itself. The NGA’s angular forms and fortress-like presence, the High Court’s soaring glass atrium, the Library’s colonnaded rationalism—all were conceived in the visual language of authority. These were not spaces for quiet contemplation alone. They were designed to project gravitas, stability, and intellectual sovereignty.

Art outdoors: the sculptural nation

The ambition to embed art into the very identity of the capital extended beyond the interiors of buildings. Public sculpture became a core feature of Canberra’s symbolic environment. The NGA Sculpture Garden, opened in stages from the 1980s onward, placed major international and Australian works along the lakeside, including pieces by Henry Moore, Fujiko Nakaya, and Bert Flugelman. The placement of sculpture here was not incidental. It was an effort to extend the gallery’s reach into the civic body of the city, reinforcing the idea that Canberra itself was a curated space.

Elsewhere in the city, public monuments began to fill out the symbolic framework: memorials to explorers, wars, political figures, and moments in federation. These sculptures, often classical or representational in style, offered a counterpoint to the modernist abstraction of the gallery’s holdings. They functioned as punctuation marks in Canberra’s larger visual sentence—a grammar of nationhood inscribed in bronze and stone.

- The NGA Sculpture Garden curated a dialogue between landscape and object, with works partially submerged, hidden in groves, or interacting with fog and water.

- The Reconciliation Place installations, developed in the early 2000s, introduced contemporary Indigenous voices into the national symbolic centre.

- The Captain Cook Memorial Jet (1968), a kinetic spectacle on the lake, fused spectacle with commemoration—another example of how the city performs memory.

The National Portrait Gallery: images of power and presence

By the late 1990s, the federal cultural agenda expanded to include not just high modernist abstraction or Indigenous traditions, but the very image of leadership itself. The foundation of the National Portrait Gallery of Australia in 1998 formalised a collection devoted to “those who have shaped the nation.” Initially housed within Old Parliament House, the NPG gained its own purpose-built structure on King Edward Terrace in 2008—a sleek, light-filled space designed by Johnson Pilton Walker.

Portraiture, by its nature, is entangled with power. In the context of Canberra, that entanglement becomes literal. Many of the figures depicted—Prime Ministers, High Court justices, cultural icons—work or worked mere streets away from the gallery. The NPG is both a mirror and a theatre of state. But its collection has gradually expanded to include more varied faces: artists, activists, scientists, and cultural workers, including previously overlooked women and First Nations leaders. In doing so, the gallery has participated in an evolving debate over who counts as nationally significant.

Unlike the NGA, which asserts its authority through global ambition and monumental architecture, the NPG’s power lies in intimacy. Its rooms are filled with eyes—meeting the gaze of the viewer, inviting recognition, or demanding reconsideration. In this way, it quietly complicates the idea of national culture as a singular, unified project.

Federal aesthetics and the problem of pluralism

For all their cultural heft, Canberra’s major institutions have often been accused of a certain remoteness—not just geographical, but curatorial. Their federal mandate demands that they represent “Australia,” but the definition of that term is contested, elastic, and historically narrow. The NGA’s early focus on Euro-American modernism; the NPG’s emphasis on political elites; the absence, until relatively recently, of community-led narratives: all these reflect the constraints of top-down cultural formation.

Yet the very permanence of these institutions has also made them responsive. Scandals, debates, and protests have shaped their acquisitions and exhibitions. As Canberra’s demographics have shifted and its cultural expectations evolved, so too have its galleries. They now host performance art, video installations, community consultations, and temporary interventions that would have seemed inconceivable in the 1980s.

The federal dream—the idea that a nation could express itself through a curated cluster of buildings—remains potent. But it no longer rests on stability alone. It now depends on the willingness of those institutions to reinterpret, to rehouse uncomfortable histories, and to listen.

What began as an architectural project is now a question of authority: who has the right to define what national culture looks like, and what new forms it might take in the decades ahead.

Chapter 4: Paint and Protest — 1970s Activism and the Aboriginal Tent Embassy

When an umbrella became an artwork

On 26 January 1972—Australia Day—that singular act of planting a beach umbrella on the lawn of Old Parliament House in Canberra marked the beginning of something extraordinary. Four Aboriginal men—Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Tony Coorey and Bert Williams—intentionally cast themselves as diplomats of dispossession and sovereignty. Their simple act of occupation became a visual provocation. They framed the occupation as an “embassy,” thereby converting Australia’s national seat of power into an improvised gallery of protest.

The visual language of dissent

What makes the Tent Embassy not just a political milestone, but also an artistic moment, is how it turned protest into a staged tableau. In a city designed with aesthetics in mind—Walter Burley Griffin’s plan, federal architecture, ceremonial axes—the Embassy quietly undercut the official grammar by translating displacement into performance. The beach umbrella became a symbol of non‑sovereignty, the lawn a gallery of grievance, and the tents themselves a kind of sculptural intervention.

The Australian‑based Indigenous artist Richard Bell later described the Embassy as “Australia’s greatest work of performance art.” Here is a key insight: what began as a protest camp also functioned as an aesthetic gesture—an artwork enacted in public space, unavoidable, improbable, deeply visual.

From umbrella to tent: escalation and visibility

The initial umbrella soon gave way to multiple tents, placards, flags. Media images of the police moving in—on 20 July and again later that month—transformed the fringed protest into a national spectacle. The Lawn in front of Parliament became one of the most photographed sites in Australia that year. The imagery of confrontation, the lines of police, protesters raising fists, the Aboriginal flag fluttering—these became the audio‑visual vocabulary of the Indigenous land rights struggle.

Interestingly, several distinct strands of aesthetic‑political crossover emerge here:

- The occupation used signage, banners, and spatial arrangement to claim presence.

- It intentionally staged itself against the backdrop of federal architecture—the seat of Australian power.

- It translated land‑rights—an abstract question—into a readable, lived, visual condition: tents on the capital’s lawns.

The embodied artwork of sovereignty

The choice of “embassy” carries weight. No treaty was ever signed with Australia’s First Peoples; this was the claim. The protesters, in choosing that word, claimed diplomatic identity within the national frame—asserting they had not ceded sovereignty, and that Australia had no right to treat them as guests. The site of the embassy thus became a contested zone of meaning: civic space converted into symbolic terrain.

In terms of art history, this moment also intersects with the wider global activism of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The assertiveness of the Black Power movement, the visual resonance of protest camps worldwide, the bridging of performance, installation, and occupation—all find echo in the Embassy. One might say that the Embassy emphasised that for Indigenous artists and activists, land is medium; country is canvas. Yet it also exposed how national institutions historically ignored that artistic dimension.

Mid‑section surprise: the art‑institution response

Despite its powerful visual presence and political urgency, mainstream art institutions in Canberra were slow to integrate the legacy of the Tent Embassy. It took decades for the protest to be referenced in curatorial frameworks, for the symbol of the tent to be included in design archives, for the banner‑images to enter gallery spaces. In a city structured around federal patronage and formal museum culture, a grassroots camp on the lawns of Parliament disrupted more than one expectation.

For example, the documentary film Ningla A‑Na (1972) captured the protests and has since been recognised as a seminal record of Indigenous activism. But the mainstream art‑historical recognition of the Embassy came much later—revealing how the art system lagged behind the political system it claimed to represent.

Public art, memory and the longer arc

As the decades passed, the Embassy site itself became part of Canberra’s cultural geography. It was registered on the Australian Register of the National Estate in 1995 as a significant political site. Its visual imprint—flags, signs, the site of protest—has been reintegrated into the visual culture of the capital. But even so, the visual legacy is still contested: images of the site continue to stir debate around recognition, erasure, and representation.

Meanwhile, artists and collectives began referencing the Embassy in their work, treating it as an origin point. For instance, Richard Bell’s installation project “Embassy” uses the tent‑form as a platform to interrogate ongoing Indigenous sovereignty. The logic of the Embassy, in other words, shifted from protest to historical reference to artistic structure.

Closing reflection: the legacy of the tent in the frames of the capital

The Tent Embassy thus functions as a hinge between activism and art, between landscape and institution, between sovereignty and spectacle. In Canberra—a city designed as a place of authority—the visual act of protest asserted something different: a claim to place, visibility, voice. The tents did not simply disrupt the plan; they whetted its edges, reminding us that the capital is also contested ground.

In the broader history of art in the ACT, the Embassy reminds us that not all art happens inside galleries. Some of the most potent aesthetic acts are those that occupy ground, that plant flags, that turn official terrain into insurgent terrain. The question the Embassy leaves us with echoes: what kinds of art and memory can the national capital sustain—and what kinds refuse to be framed?

Chapter 5: The Fog and the Frame — International Modernism in a Bush Capital

When the bush turned abstract

In the early decades of the 20th century, Australia’s visual culture was still dominated by pastoral and impressionist manners: sun‑bleached gum‑trees, Sydney Harbour light, “unspoiled” landscapes. But in the mid‑century, a shift happened — one that found especially curious footing in the capital, Canberra, where the planned city‑scape and the bush‑surrounding terrain created an unusual interface between international modernism and Australian place. Artists such as Fred Williams turned the Australian outback into form and colour refracted, spatial composition reinvented — an approach that the national institutions of Canberra, emerging in that era, were eager to engage.

The modernist field meets the bush

When Fred Williams returned to Australia in 1957 after studying in London, his ambition was not simply to paint pretty bush‑scenes. He wrote about attempting to depict the “underlying form” of the continent — its earth, rock, tree‑groupings, grid‑lines — rather than a narrative of woodland or light. In his series Upwey Landscape (1965) he sketched out what would become a signature approach: flattened ground plane, minimal horizon, expressive tonal clusters of trees. The picture wasn’t about describing bush; it was about re‑framing it.

In the context of Canberra, this kind of painting made sense. The city itself was conceived as geometry imposed on nature, with ceremonial axes, artificial lake, spatial order. The tension between built form and natural terrain, between planned ideal and seasonal reality, provided a distinct aesthetic soil. When Williams or other modernists looked at the Australian landscape they were not simply painting nature—they were grappling with form, abstraction, modern clarity.

The “regional” becomes international

One of the surprising moves of modernism in Australia was how local specificity became a pathway to international resonance. Williams’ work was shown in New York in 1977 and featured in the Museum of Modern Art, establishing his credentials beyond Australian shores. In Canberra, national institutions that were being developed during this period (see Chapter 3) began acquiring works of modernist ambition rather than simply local romantic realism.

This shift mattered: it repositioned the landscape not as a cultural idyll, but as a site of formal invention. The bush didn’t just need to be painted; it needed to be reconsidered. Artists adopted aerial or flattened perspectives, chopped horizons, introduced strip‑formats, and used abstraction to disclose another dimension of the terrain. Williams’ West Gate Bridge series (around 1970) and later the Pilbara series (1979–81) are examples of moving beyond the immediate into formised land. Wikipedia

Canberra’s canvas: institutions, acquisitions and modernist ambition

The major galleries in Canberra had a distinct rôle in this moment. The burgeoning national institutions in the capital were not simply local museums—they were charged with representing national culture and linking Australia to global art histories. That ambition meant acquiring artists who engaged modernism, abstraction, and the specific Australian condition. In this sense, the modernist turn in landscape painting aligned with the symbolic project of the capital.

For example:

- The idea that a painter could reinterpret the Australian bush in abstracted form fitted the capital’s aura of symbolic order‑making.

- The placement of modernist works in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia (opened 1982) meant that Australia was signaling it expected to engage in global visual culture just as much as regionally.

- The spatial qualities of Canberra — its wide promenades, dramatic viewpoints over the lake, its architectural clarity — created a context in which the art of abstraction and formal intervention could “play” in public but with seriousness.

Mid‑section surprise: modernism’s local friction

Even as modernism took hold, it did not simply displace older traditions without contest. Many Australians initially found the abstraction of Williams and his peers difficult. The bush had long been a cultural trope of ruggedness, identity, legend. To flatten it, tilt it, schematic‑ize it, felt almost disloyal. Yet the very city‑of‑government that hosted these institutions was built upon a plan of abstraction: axes, vistas, artificial water. So Canberra in that sense was a fertile ground for modernist landscape to evolve.

Moreover, regionalism here took an unusual shape. While many modernists in Europe turned to urban or industrial subject matter, in Australia the painted subject became the land, but the method became abstraction. It inverted expectations: the vastness of the bush required a different pictorial logic, not the sweeping sky of tradition, but tilted planes, fractured horizontals, erratic trees. Williams elaborated this approach, re‑thinking perspective. Wikipedia

Landscape, abstraction, and Australian identity in dialogue

Importantly, modernism in the bush‑capital context wasn’t just mimicry of European abstraction. It was a dialogue between place and form, where the specificity of the land compelled a new aesthetic vocabulary. Williams once noted that European traditions couldn’t simply be overlaid onto the Australian land‑mass without negotiation. This is a meaningful point for Canberra: the national capital was not simply adopting a global visual language; it was engaging a territory, asking how to represent Australia in the late‑20th‑century world.

We might summarise three tendencies in this moment:

- A shift from painterly representation to structural formulation of landscape.

- A turn from narrative storytelling to formal interrogation of place.

- The embedding of Australian visual culture into international modernist discourse.

The institutionalisation of modernist aesthetics in Canberra

By the 1980s and onwards, the acquisitions and exhibition histories of Canberra’s galleries began reflecting this modernist legacy. High‑profile landscapes by Williams and his successors entered national collections, theory and criticism turned to the question of how Australian art could be both regional and international. The capital’s cultural identity thus partly hinged on this modernist alignment.

But there were tensions too: as modernism matured, the question shifted from “can Australia produce modern art?” to “how does Australian art respond to global modernism while remaining rooted in country and context?” Australia’s modernist landscape painters laid the groundwork, and Canberra’s institutional world provided the stage.

Closing reflection: beyond the frame, the fog lifts

In retrospect, the story of modernism in Canberra is not just about a painter or a painting. It is about a cultural moment when a planned capital, still young, caught up with the promise of global art but anchored it in place. The “fog” of modernism cleared to reveal a new “frame” for the Australian landscape—structured, abstract, rigorous. And in that reveal, the bush‑capital found a visual language of its own.

When we walk around the precincts of Canberra today, when we view the lake from the axial promenade, we might sense this convergence: a city of order, a land of texture, a painting of place. And in that convergence we glimpse one layer of the art‑history of the capital.

Chapter 6: Concrete, Glass, and Stone — The Architecture of Canberra as Visual Art

When the city itself became sculpture

In the mid‑ to late‑20th century, Canberra did more than house government: it began to display architecture as if it were artwork—monuments in concrete, glass, and stone that speak as loudly as any painting. The capital’s built form emerged as a visual regime, a self‑conscious realm of civic aesthetics, where lines of sight, materials, and monumental scale were meant to articulate national identity. This chapter explores how architecture in Canberra moved beyond utility, becoming itself a medium of art.

The rise of monumental public architecture

After the federal government committed to building a purpose‑designed capital, the urban geometry laid by Walter Burley Griffin and others became the stage for expressive architecture. As institutions formed (see Chapter 3), their buildings could no longer simply serve administration—they needed to embody gravitas. The construction of major structures like the National Gallery of Australia (opened 1982) and the High Court of Australia (opened 1980) reflect this logic. The National Gallery’s building, designed by architect Colin Madigan, is described by its own sources as “a beacon of experimental design and exemplary Brutalist architecture.” The High Court similarly is described as “an outstanding example of late modern Brutalist architecture… raw massed concrete, dynamic internal movement, and strong links with neighbouring buildings and landscape.”

These buildings sit within the Parliamentary Triangle, along the shore of Lake Burley Griffin, aligning with the broad axes of the city. Their siting, form, and finish are part of the visual schema of the capital—not separate from it. Canberra’s architecture reveals the principle that the city’s infrastructure is itself a kind of curated experience.

Materials, scale, and symbolism

One striking feature in the architectural vocabulary of Canberra is the use of exposed concrete, glass panes, and geometric clarity. This aesthetic shifts buildings from mere function to statements. Consider the National Gallery: according to a recent architectural review, its building “is bold and striking, with high ceilings and beautifully exposed concrete waffle slabs. Ramps and stairs act as architectural features, as well as a reminder of the gallery yet to be explored.” The building’s outward appearance simultaneously invokes fortress‑like solidity and institutional transparency—concrete walls punctured by large glazing.

Likewise, the High Court’s atrium, ramps, and exposed structure serve as architectural theatre. The way light enters, how volumes shift, how one moves through space—all these are part of the experience. For example, its main public hall measures 24 metres high and is built from bush‑hammered reinforced concrete; the large windows frame views of Lake Burley Griffin, linking interior and exterior.

Some of the architectural gestures can be summarised as:

- Monumentality of form: large volumes, high ceilings, ramps, atria, heavy materials.

- Material honesty: exposed concrete, visible structural elements, minimal ornamentation.

- Spatial choreography: alignments, long vistas, connection to the landscape.

These elements combine to make buildings that are at once functional and symbolic—architectural works meant to be read, to be seen, to carry meaning beyond their immediate program.

Landscape, city‑plan and architectural interplay

What distinguishes Canberra’s architecture is its relationship to the city plan. The city was devised with broad axes, vistas, lakeside promenades, and green corridors. Architecture here does not sit randomly—it is embedded, framed, and sometimes suspended within that plan. The National Gallery and the High Court, for example, occupy sites that align with the water axis of the Griffins’ plan and the ceremonial avenues of the Parliamentary Triangle.

This integration means that architecture does double duty: the building is both a structure and part of the city’s visual composition. The viewer’s experience is not just entering the building—it is seeing it within its site: across the lake, from the bridge, from an elevated ridge. Architecture in Canberra participates as part of the greater “canvas” of the capital. Buildings are simultaneously objects of view and parts of a larger view.

A mid‑section surprise: aesthetic bureaucracy and risk

It may seem that such bold architecture would emerge from avant‑garde impulses, but in Canberra it emerged within highly regulated, often bureaucratic conditions. The capital’s administrators, such as the National Capital Development Commission (NCDC), guided not only planning but also the approval of major buildings. The result is that these buildings, while ambitious, also bear the marks of deliberation and risk‑aversion. The heavy use of concrete, the monumental scale, and the formal clarity can be read as safe expressions of authority rather than purely experimental.

Yet that very constraint created an interesting paradox: architecture that pushes form, but within a framework of national symbolism. The buildings are daring, but not chaotic; expressive, but official. They reflect a tension between innovation and institution. For example: the National Gallery’s brutalist credentials are well noted—but its form serves an institutional mission of national cultural representation. The architecture does not reject the establishment; rather it subverts it through form.

Public architecture, democracy, and visual politics

In many ways, architecture in Canberra is political art. The buildings of national power—the parliament, the high court, national museums—are also the largest artworks in the city. They convey messages about authority, national identity, and the public sphere. The architectural choices—materials, alignments, openness—participate in those messages.

Consider how one approaches the High Court: the rising ramp through the atrium frames your progression, the concrete walls speak of permanence, the glazing offers views outwards. The building asserts the judiciary’s place within the nation. The National Gallery, situated on the lake, frames the cultural mission of the nation, its transparent and opaque spaces reflecting accessibility and prestige.

Public architecture in Canberra can thus be read visually as:

- A demonstration of national power and cultural ambition.

- An attempt to embed democratic values (light, transparency, access) within formal structures.

- A negotiation between openness and authority, between monumentality and user‑experience.

Looking ahead: legacy and critique

While many of Canberra’s architectural landmarks are now celebrated, they also carry critical weight. The very precision and monumental scale that were once futures‑oriented now raise questions about human scale, diversity of usage, and flexibility. Some critics argue that the architecture is too formal, too monumental, too brief in accommodating evolving cultural practices. Others point to the fact that the city’s early architectural ambitions still struggle to engage with grassroots culture, informal or ephemeral art‑forms, or the everyday life of the suburbs.

Yet the legacy remains significant. Canberra’s architecture offers a rare case where the built environment is consciously treated as visual culture. For contemporary practitioners and visitors alike, the capital stands as a major site for understanding how architecture, art, planning and national identity can intertwine.

In the interplay of concrete slabs, glass facades, structural ramps and ceremonial axes, we see a city that proposes: the building is art, the city is composition, and the viewer is part of the tableau. And in that proposition lies one of the most sustained dialogues of Canberra’s art history.

Chapter 7: Regionalism and the Canberra School

A city of schools, a region of painters

In the long shadow of national institutions and federal symbolism, something quieter unfolded on the edges of Canberra’s art history: the formation of a regional visual culture—shaped not by embassies and acquisitions, but by schools, local landscapes, artist communities, and the slow development of place-based aesthetics. The so-called “Canberra School” was never a single movement, but it became shorthand for a sensibility: art grounded in the distinctive terrain of the ACT and surrounding Monaro region, informed by the changing light, dry hills, open paddocks, and conceptual rigor that came from teaching, making, and staying in the capital.

The Canberra School of Art and the idea of locality

The institutional seed of this movement was the Canberra School of Art, which gained independence in 1976 and later became part of the Australian National University. From the late 1970s onward, it cultivated a strong studio-based model of arts education. Its teaching departments—painting, sculpture, printmaking, textiles, and more—functioned as semi-autonomous artistic communities, often with nationally or internationally recognized staff who chose to base themselves in the capital.

This convergence of pedagogical intensity and regional isolation created a distinct atmosphere. Canberra was not a major market town; there was little commercial pressure, little media glare. What it offered instead was time, landscape, and intellectual infrastructure. Students and staff could pursue work in depth—responding not only to theory, but to place.

One of the enduring features of the Canberra School was its emphasis on craftsmanship and formal control. This wasn’t a coincidence. In a city dominated by architectural clarity and bureaucratic order, the arts curriculum took on a kind of counter-discipline: attentive to material, grounded in process, skeptical of fad. As a result, many of its graduates produced work that was quiet, rigorous, and visually spare—qualities often misunderstood as conservative, but better read as deliberate regionalism.

Robert Boynes and the painterly city

Among the major figures associated with the School was Robert Boynes, who began teaching there in 1978. Boynes had already established himself as a painter interested in the urban condition, drawing on Pop, photorealism, and social critique. Yet in Canberra, his work evolved—not toward sentimentality, but toward a fusion of city and place, abstraction and scene. His paintings from the late 20th and early 21st centuries, often depicting blurred crowds, glass reflections, and architectural spaces, speak indirectly to the experience of Canberra: its isolation, its bureaucratic rhythms, its distanced order.

Though not a “landscape painter” in the traditional sense, Boynes captured something essential about the Canberra condition: the interface between built structure and atmospheric dislocation. His role as educator also meant that his influence extended into the studio practices of a generation of younger artists trained at the School.

Three features often recur in the work of artists shaped by this context:

- A tendency toward reduction—a stripping away of embellishment in favor of formal economy.

- A tension between precision and atmosphere—the kind found in dry terrain and clear light.

- An interest in material honesty—responding to both landscape and the architectural textures of the city.

The regional terrain: Tidbinbilla, Namadgi, and the Monaro

While the Canberra School provided an intellectual anchor, the land around it became a recurring visual subject. The Monaro plains, with their vast skies and skeletal trees; the Namadgi ranges with their granite tors and burnt regrowth; the Tidbinbilla valley, dry and golden in late summer—these became sites of repeated return. Artists painted them not out of romantic nostalgia, but with a kind of patient, formal attentiveness.

Many regional artists adopted a stripped-down approach to landscape, often bordering on abstraction. In this, they echoed Fred Williams (see Chapter 5), but also diverged. Their paintings were less about the epic and more about quiet duration—the incremental seasons, the wind-patterns on ridgelines, the trace of watercourses across open paddocks.

It was not just painters who responded this way. Printmakers and textile artists at the School also developed vocabularies rooted in the regional palette: ochres, ash-greys, dry greens, dusk blues. Their works emerged from extended looking—repetitions of place, not as backdrop but as subject.

This mode of working helped define what came to be known informally as the “Canberra aesthetic”: not a formal movement, but a loose grouping of artists responding to similar conditions. Their shared reference was not urban grit or national myth, but the discipline of staying in one place long enough to really see it.

Marie Hagerty and the abstraction of landscape

One of the best-known graduates of the Canberra School, Marie Hagerty, took this regional attentiveness and pushed it toward abstraction. Born in 1964, Hagerty’s work is known for its sculptural forms, ambiguous volumes, and sensuous surfaces. Though her paintings do not depict literal landscapes, their curvature, earth-tones, and internal spatial dynamics feel profoundly shaped by place.

Her canvases hover between body and terrain, interior and exterior. While some critics have linked her style to Baroque painting or European modernism, the influence of Canberra’s physical environment is unmistakable—its measured light, its softened topographies, its underlying clarity. Hagerty’s work is less about depiction than about material intuition, shaped over years of working and teaching in the capital.

Like others trained or drawn to the city, she embodies a kind of visual intelligence that thrives in slow environments: work that evolves not from spectacle, but from sustained attentiveness.

The Canberra Art Workshop: localism before it was fashionable

Long before the School formalized regional practice, the Canberra Art Workshop—formerly the Canberra Art Club—provided space for painters and makers to develop their craft. Founded in the 1950s and still active today, it offered weekly life-drawing classes, studio sessions, and informal exhibitions. Many of the artists associated with the Workshop were amateur or semi-professional, but their dedication to painting the local environment gave early definition to the visual identity of the region.

This grassroots localism now looks prescient. As global art markets shifted toward hyper-conceptualism or international scale, the idea of staying put, painting paddocks, working in series, seemed outdated. Yet Canberra’s regional artists, by continuing these practices, preserved a mode of making that is now being reconsidered: slow art, local art, land-based art—not as retreat, but as resistance to cultural acceleration.

A school without a manifesto

In truth, the “Canberra School” is best understood not as a style or a group, but as a condition. It names an approach to art-making rooted in attentiveness to place, clarity of form, and pedagogical rigor. It emerged in part because of Canberra’s peculiar status: a capital city without a commercial art market, but with major institutions and high-level education. This created an unusual ecology—one where artists could develop strong, focused practices without immediate pressure to conform to metropolitan trends.

That ecology still persists, in studios and classrooms, in valley walks and ridge-line sketches, in the disciplined quiet of paintings that speak to where they were made. The legacy of the Canberra School is not about influence. It’s about attention. And in a time of cultural noise, that may be the most radical gesture of all.

Chapter 8: Paper, Earth, Light — Rosalie Gascoigne and Material Poetics

A landscape broken into language

Rosalie Gascoigne didn’t paint the land. She gathered it. She foraged, selected, tore, arranged. Her work emerged not from brushstrokes or grand compositions, but from scraps of the overlooked: weathered road signs, linoleum fragments, dried grasses, corrugated iron, wooden crates. Through this process of salvage and composition, she created a body of work that is among the most original and enduring in Australian art. And she did it from a place that rarely lends itself to artistic mythology: the dry, wind-bent hills outside Canberra.

Gascoigne arrived in Canberra in 1943, moving with her husband, astronomer Ben Gascoigne, to Mount Stromlo Observatory. At first, she found the place austere. “It seemed to me very flat, very dead,” she once said. But over time, the landscape began to speak. She came to see it not in terms of lushness or drama, but of rhythm, silence, and structure. “All air, all light, all space and all understatement” was how she came to describe it. That understated terrain—its dry fields, burnt trunks, and brittle grasses—would become the basis for her entire artistic vocabulary.

Becoming an artist after forty

Gascoigne’s trajectory was deeply unconventional. She did not attend art school or enter the art world young. Her first serious works emerged in the 1960s, after years of working in ikebana (Japanese flower arrangement), which shaped her sensitivity to form, negative space, and the resonance of materials. It wasn’t until 1974, in her late fifties, that she held her first solo exhibition at Gallery A in Sydney. Within a few years, she would be included in major state and national collections. In 1982, she represented Australia at the Venice Biennale alongside Peter Booth—a milestone for any artist, but particularly for one who had only recently begun exhibiting.

The late arrival was not a liability. It gave her work a maturity, a confidence, and a total indifference to fashion. She wasn’t chasing movements. She was chasing the land. More precisely: its textures, its disintegration, its unsaid language. Canberra, for all its bureaucratic abstraction and sculpted precincts, gave Gascoigne what she needed—access to overlooked materials and a region whose visual spareness mirrored her own formal restraint.

The Crop I and the art of residue

One of Gascoigne’s earliest breakthrough works, The Crop I (1976), consists of a grid of dried salsify seed heads arranged atop a rusted sheet of iron. At first glance, it seems fragile, even accidental. But the order is precise, the materials deliberate. Salsify—an introduced weed—grows widely across the Monaro plains, and Gascoigne collected it obsessively. In The Crop I, she takes what the land sheds and makes it art.

This is more than assemblage. It is a kind of fieldwork. Gascoigne treats the rural terrain not as subject but as source. The grasses are not rendered; they are presented. Their placement on rusted metal reads like a score, or a fragment of some old, broken sign—perhaps left beside a paddock, forgotten, and brought back into visual life. The result is both minimal and emotional: it hums with loss, dryness, order, and survival.

Gascoigne’s works often carry this doubleness. They are made of scraps, but they are never casual. She arranges each piece with an almost linguistic precision—as if she is editing a text written in weed stems, flaked paint, road signs, or splintered linoleum.

Flash Art and the road as sentence

In her later work, Gascoigne turned increasingly to painted and printed materials—particularly discarded retro-reflective road signs. In Flash Art (1987), now held by the National Gallery of Victoria, she arranges pieces of yellow reflective signage in a loose grid. The words are incomplete—fragments of directions, warnings, and bureaucratic messages. But seen together, they become something else: a visual rhythm of language, abstraction, and landscape.

The signs had once instructed or warned motorists across rural New South Wales. On highways and country roads, they were part of the visual and semantic landscape of state control. Gascoigne collects these fragments, not to critique them overtly, but to recompose them—shifting function into feeling. The hard-edged, directive language of the road is turned into a shimmering, flickering surface that reads more like poetry than signage.

Flash Art exemplifies one of Gascoigne’s great innovations: she makes language visual without illustration. She turns public material into private resonance. The work is political not through message, but through transformation. She does not denounce; she remakes. In doing so, she reframes the aesthetic of rural infrastructure as something elegiac, almost lyrical.

First Fruits and the tactile sublime

Perhaps her most quietly moving works are those that use found paper: worn linoleum, discarded tar paper, old fruit-box labels. In First Fruits (1991), held by The Met in New York, Gascoigne arranges painted tar paper into soft, warm tones—reds, browns, yellows—torn and mounted on plywood in a loose but deliberate rhythm. The title suggests offering, yield, perhaps even sacrifice. There’s no image, but the piece evokes orchard rows, fruit crates, peeling walls—material afterlife.

Again, the rural is not depicted but embedded. The paper comes from that world; its decay is part of its power. Gascoigne had no interest in permanence. Her work embraced weathering, damage, and patina. She often said she liked materials that had “been somewhere and done something.” Her eye was for residue—for what remains after function ends.

That sensibility found deep harmony with Canberra and its surroundings. The high-country dryness, the silence of paddocks, the textured erosion of man-made signs in the elements—all these were mirrored in her practice. Even the act of driving—scanning roadsides for materials, pulling over to collect a particular crate or sign—became part of her aesthetic method. She worked with the land’s refuse, not its vistas.

Venice and the matter of international recognition

When Gascoigne was chosen to represent Australia at the 1982 Venice Biennale, many in the art world were startled. Here was a woman in her mid-sixties, working from a home studio in Deakin, creating wall-based compositions from detritus. And yet the response was profound. Her works, presented without bombast, stood out for their clarity and their connection to place. They didn’t illustrate the Australian landscape; they embodied its logic.

In Venice, the international audience encountered something unfamiliar: a kind of abstraction that was neither doctrinaire nor decorative. It had rhythm, but not pattern. It had resonance, but not metaphor. It was neither conceptual nor expressionist. Instead, it felt like memory, distilled into material.

This reception cemented her position not only in Australia but globally. But Gascoigne never played to the international scene. She continued working from Canberra, often revisiting the same roads, signs, weeds, and scraps. Her attention never wavered.

A poetics of understatement

Rosalie Gascoigne’s art is not grand. It does not seek to dazzle or explain. It is, like the land that shaped it, quietly overwhelming. Her work insists that looking closely—at woodgrain, at weathered paint, at the way grass breaks from iron—is a political and poetic act. That the materials of the rural roadside can be made to speak, not only of place, but of care.

In a national capital defined by its architecture, its institutions, its carefully plotted avenues, Gascoigne’s work offers another vision: not the planned, but the found. Not the statement, but the arrangement. Her art is not a claim—it is a question. What does the land leave behind? And what can we make from its remnants?

That question continues to echo in the galleries and landscapes of Canberra. And Gascoigne’s answer, built from paper, earth, and light, remains among the most profound.

Chapter 9: Off the Wall — Street Art, Counterculture, and Suburban Interventions

A city of law meets a culture of the unsanctioned

Canberra is a city built on regulations. Every street corner, every stretch of verge, every public bench is accounted for in some bureaucratic document. But even in a city of codified order, a second visual life has emerged — one made not by architects or curators, but by stencil artists, spray-can painters, sticker bombers, and muralists. Across laneways in Braddon, underpasses in Civic, skateparks in Belconnen, and construction hoardings in Woden, street art has carved out a stubborn presence. If Canberra’s official institutions shape national culture, these walls speak a local language — fast, ironic, coded, and often fleeting.

This chapter tracks the rise of street art and countercultural expression in a city better known for public service uniforms and parliamentary procedure. It is a story of tension and accommodation, vandalism and curation, spontaneity and slow shifts in civic identity.

Legal walls and visual breathing room

Unlike many other Australian cities, Canberra has embraced the idea of “legal walls” — designated zones where street artists can paint without fear of prosecution. The ACT Government’s own website outlines the policy: “Commissioned and permitted street art is legal. Unsolicited graffiti is not.” It’s a tidy division, but in practice the boundary between sanctioned and unsanctioned is porous.

The suburb of Braddon has become one of the city’s most active hubs for street art. In particular, Tocumwal Lane — a rear laneway that snakes behind cafés and boutiques — serves as both open-air gallery and experimental zone. Here, the walls shift weekly. Layers accumulate. The city breathes colour and contradiction.

What’s distinctive about Canberra’s approach is how it reflects both control and concession. The legal walls offer permission, but also containment. They keep the wildness of graffiti within bounds. Yet this hasn’t stifled energy. Artists use these walls to test techniques, send coded messages, stage conversations with one another. The space becomes more than surface — it becomes scene.

Three effects of the legal-wall policy can be seen clearly:

- Ephemerality is accepted, even celebrated. Artists paint over each other without rancour. The wall lives.

- Community emerges from collision. Artists meet, argue, collaborate, form crews.

- The line between official and subversive blurs. Commissioned works coexist with spontaneous tags and burner pieces.

Canberra may be orderly, but its walls don’t always obey.

Chris “Walrus” Dalzell and the art of intervention

One of the more influential figures in Canberra’s street art scene is Chris “Walrus” Dalzell, known for his unusual public interventions. Rather than working solely with paint, Dalzell pioneered a form of “wrap art” — creating large spider web–like structures with industrial cling film, stretched across alleyways and urban gaps. These installations, often unannounced and brief, challenged viewers’ sense of public space.

Dalzell’s broader practice includes murals, typographic stencils, and performance-based works. But his contribution lies less in any one piece than in his approach. He treats the city as mutable — not a finished product, but a provisional surface. His works remind us that even in the heart of a planned capital, disruption is always possible. And perhaps necessary.

Like many street artists, Dalzell’s relationship with legality is ambivalent. Some of his works have been sanctioned; others not. But all of them gesture toward a different vision of urban life: one where temporary beauty, risk, and coded communication hold value alongside the enduring monuments of state.

Braddon, Belconnen, and the suburban surface

Street art in Canberra has followed the flows of youth culture, development, and transport. In Braddon — now a gentrified suburb with artisan bakeries and boutique clothing stores — murals bloom across building sides, some commissioned, others not. Artists riff on popular culture, local politics, and sheer aesthetic pleasure. The scale varies: one day, a small sticker; the next, a ten-metre wall.

In Belconnen, the skatepark near Lake Ginninderra has become a key node for aerosol art. Unlike the polished muralism of Braddon, Belconnen leans into the traditional graffiti lineage — throw-ups, wildstyle, tags. Its rougher edge reflects a different part of Canberra’s youth scene: less curated, more tribal. This is where graffiti maintains its link to subculture — to skate crews, hip-hop nights, and unpermitted expression.

Other suburbs — Tuggeranong, Woden, Dickson — have their own pockets. Underpasses, train stations, and abandoned infrastructure serve as informal canvases. A walk through any of these zones reveals the surprising reach of street art across the capital. It is not centralised, not institution-bound. It emerges where it can.

Mid-section surprise: from mural to monument

One of the most unexpected developments in Canberra’s street art history is its migration into institutional spaces. The National Gallery of Australia, once a bastion of modernist orthodoxy, now includes street-inspired works in its acquisitions and exhibitions. In 2021, the NGA exhibited works by Lister, Phibs, and other major Australian street artists as part of its push to reflect the full spectrum of contemporary visual culture.

What was once defined as vandalism now hangs beside canvases.

This shift reflects not only institutional change, but public appetite. As more residents and tourists encounter high-quality murals on city walls, the old dichotomies—graffiti vs. art, illegal vs. legitimate—begin to collapse. The city no longer needs to choose between monumentality and transience. It can have both.

And indeed, some street art in Canberra is now monumental. Large-scale murals—some stretching across multiple stories—have become permanent fixtures. Artists like Byrd, Giraffo, and Zukoe have produced works that blend stylised realism with abstract forms, offering visual landmarks for entire precincts.

Rebellion in a capital city

What makes street art in Canberra particularly striking is its context. This is not Melbourne or Berlin—a city where counterculture was always part of the civic brand. It is the capital of a highly administered nation, built on ideals of order, consensus, and visual coherence. That street art thrives here is a kind of defiance. Not loud, not violent, but persistent.

Even sanctioned murals carry a charge. They remind viewers that art doesn’t need to wait for funding rounds or gallery walls. It can appear overnight. It can fade, be painted over, re-emerge. It can speak to small publics—crews, neighborhoods, Instagram followers. It can live in layers, jokes, tags, motifs.

In a city of planned vistas and choreographed memory, street art writes its own unsanctioned histories. It tells us who is here now, who has something to say, who refuses to be ignored.

A closing gesture: colour in the cracks

Ultimately, street art in Canberra is a record of friction. Between regulation and improvisation. Between permanence and the ephemeral. Between the grand structures of state and the small claims of voice.

It turns loading docks into galleries. It turns teenagers with sketchbooks into curators. It turns a planned capital into something unpredictable. And that unpredictability—however brief, however coded—is a kind of freedom.

In the cracks of the bureaucratic city, colour finds its way.

Chapter 10: The Canberra Biennials and Curatorial Experiments

From lakefront to installation: staging art in the open city

In Canberra, the visual arts have long existed within controlled architectures—galleries, institutions, ministries, chambers. But in recent years, a parallel impulse has emerged: to place contemporary art into the landscape, to let it intervene directly in the structure of the city. This impulse found its fullest expression in the Canberra Art Biennial, formerly known as contour 556, a curatorial platform that uses the city’s designed environment as both stage and subject. Here, the lawn becomes a plinth, the shoreline a gallery, and the capital itself an active participant in the artwork.

Launched in 2016 and rebranded as the Canberra Art Biennial in 2022, the event represents a rare convergence: site-responsive contemporary art, curatorial experimentation, and civic landscape. In contrast to traditional biennials housed within industrial venues or white cubes, this one takes place across Canberra’s central spine—Lake Burley Griffin, the National Arboretum, Constitution Place, and other open-air settings designed for ceremony, movement, and monumental sightlines. The result is not a decorative overlay, but a kind of conversation: artists responding to a city that was itself designed as a symbolic object.

Contour as critique: a curatorial rethinking

The name “contour 556” referred to the contour line that defines the planned water level of Lake Burley Griffin—556 metres above sea level. It is a small detail with large resonance: a reminder that even the lake is artificial, designed as part of Griffin’s geometrical vision. The biennial, from its inception, sought to use this symbolic and literal level as a curatorial threshold. By placing artworks along the lake and surrounding precincts, the biennial explored the uneasy border between natural terrain and bureaucratic design, between planned city and lived space.

From early editions, artists engaged directly with this context. Some used sculpture, some sound, some ephemeral installation. Others brought in performance, narrative, or durational works. In all cases, the biennial created a temporary re-mapping of Canberra—where known spaces became temporarily strange, charged with new meaning.

- At the 2022 edition, works such as Katrina Tyler’s “Event Horizon”, with its polished reflective surface installed near the lake, turned the viewer’s gaze back onto the city’s layout.

- In earlier years, installations at Reconciliation Place and the National Arboretum brought Indigenous and ecological questions into the formal heart of the capital.

- Performative works unfolded along pedestrian routes, challenging the hierarchy between viewer, citizen, and participant.

The act of curating such an event is itself a disruption of institutional norms. Here, art was not selected to sit safely within frames and labels. It was commissioned to work in tension—with wind, scale, politics, and sightline.

2024: Archives, bodies, and shifting thresholds

The 2024 Canberra Art Biennial, held between 27 September and 26 October, expanded both scale and ambition. With over 60 artists from Australia and abroad, the event moved fluidly between established venues (the National Film and Sound Archive, Constitution Place, the Canberra Museum and Gallery) and open civic spaces. Installations spanned media: sculpture, sound, video, text, and performance. But it was not just the volume of work that marked the Biennial’s evolution—it was the curatorial coherence.

One of the most compelling projects was “Witness, Collector, Archivist, Narrator”, curated by the duo sydenham international (Consuelo Cavaniglia and Brendan Van Hek). This exhibition, housed across multiple sites, focused on the archival impulse in contemporary practice: artists as recorders, as re-makers of lost or fragmented histories. Works explored trauma, recovery, memory, and silence—resonant themes in a city defined by political amnesia and formal documentation.

Placed within Canberra’s official structures, these artworks interrogated the very idea of the archive—not as a sealed vault, but as a porous, living structure. For a city built on record-keeping, this curatorial gesture was radical. It posed a question: what gets remembered here, and who gets to narrate it?

Mid-section surprise: when institutions follow the streets

Historically, Canberra’s major art institutions—particularly the National Gallery of Australia and the National Portrait Gallery—have operated on traditional curatorial models: planned exhibitions, housed collections, formal publications. But as the Biennial model gained momentum, even these institutions began experimenting with more porous approaches.

For example, in recent years:

- The NGA commissioned site-specific works that respond to their exterior spaces, including pieces that extend the exhibition outdoors and into public view.

- The National Film and Sound Archive partnered with the 2024 Biennial to host contemporary performance and sound works, stepping away from archival safekeeping into artistic dialogue.

- The Canberra Museum and Gallery supported projects that bridged historical material with contemporary visual expression, echoing the Biennial’s ethos of overlap and tension.

This movement reflects a larger shift: the boundary between street-level art and institutional exhibition has become permeable. Curators now walk the lake as much as the galleries. Programming considers light, wind, weather, and accidental audiences. The citizen becomes a viewer not by entering a building, but by stepping out of one.

The planned city as open-air gallery

What makes the Canberra Art Biennial unique is its setting. The city itself is a work of design, and the Biennial treats it as such. Instead of seeing public space as a passive backdrop, the curators engage it actively—sometimes in tension, sometimes in harmony.

This yields curatorial strategies not easily replicated elsewhere:

- Artworks must contend with axial vistas, government buildings, and symbolic alignments.

- Artists work with (or against) the geometry of Griffin’s plan—interrupting long views, responding to landforms, engaging artificial lakes.

- The city’s deep quietness becomes a material in itself: silence as a frame, stillness as contrast.

In this way, the Biennial becomes more than a festival. It becomes an investigation of the capital’s form. Artworks are not simply placed—they are sited, embedded in questions of civic vision, colonial overlay, and national symbolism.

Curatorial ambition as civic critique

The Canberra Art Biennial reveals how curators in the capital are no longer content to follow inherited scripts. The city, long seen as overly planned or visually staid, becomes instead a site for questioning. Why was this built here? Who was excluded from this design? What kind of art can enter this space? The best curatorial gestures now aim not to answer, but to make the question felt—bodily, visually, spatially.

And perhaps this is where Canberra’s art scene, once synonymous with bureaucratic order, has found its most surprising vitality: in the act of gentle confrontation. By placing art into the symbolic machinery of the capital, curators ask us not to look past Canberra, but to look directly at it. And to see what art can do—not as decoration, but as intervention.

Chapter 11: Institutions in the Age of Scandal and Reappraisal

The pedestal shakes

For decades, the great cultural institutions of Canberra stood as monuments of trust. Built from concrete, marble, and consensus, they embodied the promise of a national cultural identity—one that would be measured, considered, and above politics. But in recent years, that promise has wavered. The very institutions designed to enshrine Australia’s artistic and historical legacy have become flashpoints: for questions of ethics, authority, ownership, and accountability. Scandals have emerged not from the margins but from the centre—within the National Gallery of Australia, the country’s most significant art museum.

These moments of institutional reckoning have revealed something essential: that no gallery is above scrutiny, and that the aesthetic, the ethical, and the political are not easily separable in the capital city of a democratic nation. Canberra’s institutions now find themselves forced to adapt—under pressure not just to present art, but to justify how it is made, who it is by, and how it got here.

The APY controversy: authorship under interrogation

In 2023, the NGA became the focus of a deeply divisive episode involving the APY Art Centre Collective, a network of Indigenous-owned art centres representing artists from the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) lands in remote South Australia. The controversy began when allegations surfaced that some of the Collective’s works—created ostensibly by senior Aboriginal artists—had been interfered with or “touched up” by non-Indigenous studio assistants. The allegations, first reported by The Australian, implied that artworks exhibited and sold as expressions of cultural authority may have been compromised in authorship.

The claims ignited fierce debate within the art world, the Indigenous community, and beyond. Critics raised concerns about authenticity, transparency, and the commodification of Aboriginal cultural production. The NGA, which had commissioned and exhibited works from the Collective, launched an internal review. Its eventual finding—publicly released in August 2023—cleared the Collective of wrongdoing, concluding that no improper interference had occurred. But the damage was done. Several senior figures resigned from the NGA’s Indigenous Advisory Group. Trust, once eroded, proved difficult to restore.

The episode did more than cast doubt on specific works. It raised systemic questions:

- Who has the right to speak for Indigenous authorship in institutional spaces?

- What constitutes a collaborative practice in a collective model?

- How does the museum frame Indigenous labour without reducing it to ethnography or spectacle?

For the NGA, the fallout was a reckoning. For Canberra’s art world, it was a lesson in how institutional frameworks can either support or fail the artists they purport to uplift.

Provenance, restitution, and the return of the looted object

The ethics of ownership extend beyond contemporary art. In the past decade, museums worldwide have faced increasing pressure to investigate and, where necessary, return artworks acquired through colonial extraction or illicit markets. The NGA has not been immune.

In 2018, the Gallery was forced to return a 900-year-old bronze statue of the goddess Shiva to India, after revelations that it had been looted and sold through disgraced art dealer Subhash Kapoor. That act of repatriation was followed by others—including, most notably, in 2023, when the NGA announced it would return three Cambodian bronze sculptures, suspected of having been stolen during the Khmer Rouge era.

These cases are not isolated incidents. They represent a larger institutional challenge: how to manage a collection built, in part, through opaque networks of international art dealing, at a time when transparency is not optional, but mandatory. The NGA’s own public statements have acknowledged this shift. Provenance research is no longer a curatorial luxury—it is a fundamental responsibility.

The implications are profound:

- Major gaps have opened in the national collection as high-profile works are returned.

- Acquisition policies are under stricter review, requiring clearer documentation and ethical due diligence.

- Public trust has become contingent not on what is displayed, but how it was acquired.

Canberra’s cultural prestige now rests on a paradox: the same institutions that once asserted the nation’s artistic legitimacy must now interrogate the legitimacy of their own foundations.

The tapestry and the covered flag: free expression under pressure