Brisbane, the capital of Queensland, occupies a distinct position in Australia’s artistic ecosystem. Often overshadowed by the larger and more internationally recognized cultural centres of Sydney and Melbourne, Brisbane has nonetheless developed an art history that is entirely its own — a story of adaptation, resilience, and regional pride. It is a city that has historically punched above its weight, cultivating a vibrant artistic scene shaped not just by its subtropical climate and geographic isolation, but also by its deep historical roots, from pre-colonial traditions to contemporary expression.

While Brisbane may have long been viewed as a provincial outpost in the broader Australian imagination, that perception has changed steadily, especially since the late 20th century. Today, the city is home to internationally respected institutions such as the Queensland Art Gallery and the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), as well as a thriving network of artist-run spaces, festivals, public commissions, and university art schools. But to understand how Brisbane arrived at this point, it’s necessary to trace a complex narrative that spans Aboriginal artistic traditions, colonial ambitions, and a series of cultural turning points that shaped the city’s creative identity.

One of the most striking features of Brisbane’s artistic development is the influence of its landscape. Located along the winding Brisbane River and surrounded by rugged ranges, lush bushland, and open skies, the environment has long inspired visual artists. From early colonial surveyors sketching topographies to contemporary painters capturing the play of light across the hinterlands, the natural world has remained a central muse. This deep connection to place has helped foster a uniquely Brisbane aesthetic, one that leans into texture, colour, and light rather than the urbane abstraction more typical of southern metropolises.

Geographic distance also played an important role in defining Brisbane’s art world. For much of its early history, the city was isolated not only from international centres of culture but also from its own national counterparts. This distance, though initially a disadvantage, would eventually become a creative advantage. Artists were not beholden to the rigid expectations of the southern states and could explore styles, mediums, and themes with a freedom that sometimes led to innovative departures. This autonomy is particularly evident in Brisbane’s contributions to public sculpture, expressionist painting, and community-based art practices that reflect the city’s social dynamics without becoming dogmatic or overly academic.

Institutional support — or the lack thereof — has also helped shape the city’s art history. The founding of the Queensland Art Gallery in 1895 was a landmark moment, but for many decades it operated with limited resources and modest ambitions. It wasn’t until the late 20th century, with the establishment of GOMA and the rise of state-backed cultural programming, that Brisbane began to assert itself as a national cultural player. Yet even before these flagship institutions took root, the city’s art scene was bolstered by grassroots activity: artist collectives, workshops, studio spaces in repurposed buildings, and university art departments that served as incubators for new talent.

Moreover, Brisbane’s cultural identity cannot be separated from its particular demographic and historical context. Unlike the mercantile wealth of Sydney or the European-tinged sophistication of Melbourne, Brisbane developed as a working city with strong ties to agriculture, mining, and the military. These practical foundations influenced the kinds of stories Brisbane artists told, and the ways they told them. There’s often a directness in Brisbane’s visual culture — an embrace of materiality, a sense of place, and a grounded perspective that doesn’t strive for cosmopolitan approval. This character can be traced through the earthy palette of mid-century painters, the large-scale murals that began appearing in the 1980s, and the rise of site-specific installations that take Brisbane’s built environment as their canvas.

At the same time, Brisbane’s artists have never been parochial. As international travel became more accessible in the post-war era, many artists trained abroad and returned with new influences, blending global movements with local concerns. This cross-pollination created a fertile environment in which Brisbane art could mature — not by mimicking Sydney or London, but by developing its own visual language. The result is a city that has long operated on a different wavelength, carving out a space for itself within the broader story of Australian art.

Brisbane’s art history is not a linear progression, but rather a series of overlapping layers. Aboriginal creativity, colonial ambition, post-war migration, educational expansion, and global engagement have all played their parts. These influences are visible not only in gallery collections but also in the very fabric of the city: in the public sculptures along the riverwalk, the murals on alleyway walls, and the temporary installations that turn Brisbane’s festivals into open-air exhibitions.

In short, Brisbane’s art scene reflects the city’s identity: adaptive, expressive, and quietly confident. It is a story of artistic practice rooted in place, informed by history, and guided by the independent spirit of its people.

Pre-Colonial Visual Culture of the Turrbal and Jagera Peoples

Long before the arrival of Europeans in the Brisbane River basin, the land was home to the Turrbal and Jagera peoples. These Aboriginal groups possessed a rich visual culture deeply tied to the landscape, the Dreaming (spiritual narratives about creation and law), and the rhythms of daily life. Though their artistic legacy was largely overlooked or dismissed in the early years of colonization, archaeological and ethnographic evidence reveals a vibrant and complex system of expression that formed an integral part of community identity, knowledge transmission, and spiritual life.

Unlike the Western tradition of art for art’s sake, the visual culture of the Turrbal and Jagera peoples was practical, symbolic, and inseparable from cultural practice. Art was not confined to canvas or gallery — it existed in ceremonial objects, carved trees, ground engravings, ochre paintings, and ephemeral sand drawings. Each form had a function, often tied to initiation rites, totemic law, or the mapping of country. The materials were naturally sourced: red and yellow ochres, white pipe clay, charcoal, and plant resins, applied to bark, rock surfaces, bodies, and tools.

One of the most significant aspects of this visual culture was its rootedness in oral tradition. A carved boomerang, a painted message stick, or a body marked with ochre conveyed meaning that was intelligible only within the context of shared stories and ancestral lore. These visual forms were mnemonic devices as much as they were aesthetic expressions — tools for remembering lineage, teaching young people, and maintaining social cohesion across generations.

In the region now known as Brisbane, rock art sites and scarred trees bear silent witness to these traditions. Though many were destroyed or displaced during urban expansion, some still survive along the banks of the Brisbane River and in nearby ranges. These remnants are not simply historical artifacts; they are active sites of cultural continuity for descendants of the Turrbal and Jagera. Through contemporary initiatives in cultural heritage preservation, these sites are being mapped, studied, and in some cases, revitalized through intergenerational teaching.

Notably, the absence of permanent structures or monumental sculptures in traditional Aboriginal art has often led outsiders to underestimate its sophistication. But the symbolic systems employed by the Turrbal and Jagera are intricate. A single pattern — a concentric circle, for instance — could simultaneously refer to a waterhole, a place of ceremony, and the presence of ancestral spirits. This multilayered semiotics is comparable to medieval European iconography, except it is far older and tied to a living cosmology that continues to shape the worldview of Aboriginal people today.

Seasonal rhythms also influenced artistic output. Ceremonial gatherings, or corroborees, often involved elaborate body painting, dance, and song — all interwoven into a visual spectacle meant to connect participants with the Dreaming and with each other. Designs used in these events were not random or decorative but held strict lineage rights; only certain individuals could reproduce particular patterns or motifs. This coded aspect of design made the visual culture both a form of spiritual law and a safeguard of community integrity.

With colonization came enormous disruption to these practices. Displacement, disease, and government policies eroded the traditional transmission of knowledge. However, the visual culture of the Turrbal and Jagera peoples was never fully extinguished. Instead, it adapted. In the 20th and 21st centuries, many Aboriginal artists from the Brisbane area have drawn on traditional symbols and methods while also adopting contemporary materials and formats. These include canvas paintings, digital media, and public murals — mediums that allow the continuation of cultural knowledge in a changing world.

Artists such as Laurie Nilsen (a Manandangi man with strong connections to the southeast) and Gordon Hookey (Waanyi) have worked to foreground Aboriginal perspectives in the visual arts, blending traditional motifs with political commentary and humor. While not always directly descended from the Turrbal or Jagera, such artists have helped re-establish Brisbane as a site where Aboriginal visual culture is not only remembered but actively reinterpreted.

Meanwhile, institutions in Brisbane have begun to recognize and support these cultural traditions more visibly. The Queensland Museum and GOMA have expanded their collections and exhibitions to include both traditional artifacts and contemporary Aboriginal art. Collaborative projects with elders, language keepers, and community leaders have also played a role in ensuring that cultural authority remains with Aboriginal people themselves, rather than being interpreted solely through a Western academic lens.

It’s important to understand that Aboriginal art is not static. What is sometimes misclassified as “traditional” is, in reality, part of a living and adaptive system. The visual culture of the Turrbal and Jagera peoples continues to evolve — not in opposition to modernity, but as a dialogue with it. In this sense, the art of Brisbane begins not with colonial painting or Federation architecture, but with tens of thousands of years of Aboriginal visual knowledge embedded in the land, the stories, and the people who still call it home.

Early Colonial Art and Visual Documentation (1820s–1860s)

The visual story of colonial Brisbane begins not in grand studios or academies, but in the sketchbooks of explorers, military officers, and surveyors. In the decades following the establishment of the Moreton Bay penal colony in 1824, visual documentation was a tool of control, mapping, and communication as much as it was an artistic pursuit. The early colonial art of the Brisbane region is defined by observation — of the land, its resources, and the people who lived there. Though rarely celebrated in modern art history texts, these early works form a critical foundation in understanding how European settlers perceived, and attempted to claim, the territory.

Initially founded as a penal outpost for the most recalcitrant convicts from New South Wales, the Moreton Bay settlement was isolated and austere. Yet, even within these stark circumstances, there were those tasked with producing visual records. Officers such as Edmund Lockyer and surveyors like Henry Wade sketched rivers, flora, topography, and native camps as part of their official duties. These were not works of artistic invention; they were cartographic and ethnographic in nature — practical images meant to inform colonial administrators in Sydney and London of what this distant outpost contained.

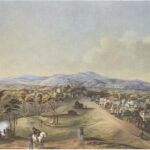

These early drawings, often executed in graphite, watercolour, or ink, tend to favour clarity over style. The composition is typically straightforward: a river bend with a few boats, a mission hut framed by gum trees, or Aboriginal figures depicted in postures of curiosity or exchange. While this work lacks the romanticism found in the colonial landscapes of the Blue Mountains or Tasmania, it holds value for its documentary realism. Through them, we see the Brisbane River as it was in its pre-urban state — winding past dense bushland, punctuated by the rough geometry of tents and storehouses.

One figure who stands out from this period is Conrad Martens, the English painter who visited the Brisbane River area in the 1850s. Though better known for his work in Sydney and for having served as the ship’s artist on HMS Beagle (alongside Charles Darwin), Martens produced a small body of work in Moreton Bay that demonstrates a refined artistic sensibility. His watercolours capture both the vastness and quietude of the Queensland environment, hinting at a more poetic, albeit European, vision of the land.

It’s worth noting that the colonial era’s visual record is not neutral. While many images aimed to document, they also contributed to a narrative of settlement and progress — a vision in which the land was gradually “tamed” and Aboriginal presence either romanticized or erased. For instance, early paintings and lithographs often include Aboriginal figures as decorative elements, placed at the margins of otherwise European-centred compositions. In this way, art became part of a broader cultural effort to legitimize colonial expansion.

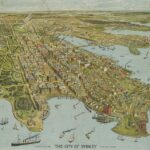

By the 1840s and 1850s, as Moreton Bay transitioned from a penal colony to a free settlement, a new class of amateur and semi-professional artists began to emerge. These included educated settlers, missionaries, and visitors who documented Brisbane’s growing townscape. The images from this period begin to show houses with pitched roofs, river steamers, and small churches — the signs of a fledgling society taking root. Many of these images were reproduced as engravings in colonial newspapers or sent back to Britain to assure investors and families of the colony’s promise.

A fascinating example of this documentary impulse is the illustrated travelogue. In the mid-19th century, visitors and colonial officials often kept journals that combined writing with sketches of local scenes. These were not meant for public exhibition but as personal accounts — yet today, they serve as valuable artifacts of Brisbane’s visual evolution. Works like these often blend empirical observation with the aesthetic instincts of the traveler, resulting in drawings that capture both the unfamiliarity and allure of the Queensland bush.

The dominant aesthetic influence on these early colonial images was not academic art but British naturalism and the picturesque. The artists — many of them military men or amateur draughtsmen — had been trained to value clarity, proportion, and detail, reflecting the Enlightenment-era ideals that still shaped European thought. This meant that even in their representations of rugged terrain or Aboriginal camps, the compositions were orderly and composed. The Brisbane River, in particular, was frequently rendered as a gentle, navigable waterway — a visual metaphor for the civilising mission of colonial rule.

However, there is also a subtle shift detectable in the later part of this period, as the population of free settlers increased and Brisbane began to take shape as a town rather than a camp. Artists started to view the land not merely as a subject of documentation but as something to be appreciated. The tone of watercolours softens; the compositions become more lyrical. In this, we can see the earliest seeds of a Queensland landscape tradition — one that would fully bloom in the coming century.

In short, the early colonial art of Brisbane was not about personal expression or innovation. It was about observing, recording, and explaining a new world to distant audiences. While these works lack the polish of later artistic movements, they offer invaluable insights into how settlers saw the land and their place within it. They are fragments of a visual culture in formation — tentative, functional, and deeply entangled with the colonial project.

The Rise of Local Art Societies and Schools (1870s–1900s)

By the 1870s, Brisbane had emerged from its penal origins and established itself as a free-settler township with growing civic ambitions. As rail links extended inland and the population swelled, the city began cultivating the institutions that signified a mature society — libraries, museums, theatres, and, crucially, art societies. It was during this period that Brisbane took its first decisive steps toward creating a sustained artistic culture, one that reached beyond documentation and toward education, exhibition, and the professionalisation of art practice.

The development of local art societies was a significant milestone in this process. These organisations served as both community hubs and platforms for aspiring artists. The earliest such body in Brisbane was the Queensland Art Society (QAS), founded in 1887. Its establishment marked a turning point in Brisbane’s cultural history — no longer would art be the isolated hobby of a few well-educated settlers or visiting Europeans. Instead, the QAS provided structure, advocacy, and a formal outlet for local talent to exhibit and engage with their peers.

The QAS was founded by a group of artists and patrons who recognized the need for an official organisation to support visual art in Queensland. Among the society’s early members were R. Godfrey Rivers, L.J. Harvey, and Oscar Friström — figures who would leave a lasting imprint on the city’s cultural identity. While modest in its early operations, the society held regular exhibitions, often in borrowed or shared spaces, and played an essential role in nurturing Brisbane’s nascent art scene.

The society also functioned as an informal art school. Before the creation of dedicated institutions, artists in Brisbane often trained through apprenticeships, evening classes, or private tuition arranged through societies like the QAS. This grassroots model was not without its limitations, but it helped to democratise art education. Men and women from a range of backgrounds — not just the wealthy elite — were given access to drawing and painting instruction. Such classes emphasised technical skill, still-life composition, figure drawing, and the plein air tradition, reflecting British academic norms of the time.

As Brisbane grew, so too did its appetite for cultural infrastructure. In 1895, the Queensland National Art Gallery (now the Queensland Art Gallery) was formally established, initially housed in the Brisbane Town Hall before moving to the Exhibition Building. While still underfunded and small compared to its southern counterparts, the gallery’s founding was a symbolic victory — it signaled that art was no longer an afterthought in the colony’s development but part of its civic and intellectual fabric.

Another key institution in this period was the Brisbane Technical College, which began offering formal art instruction in the 1880s. This was one of the first government-backed efforts to train artists in Queensland. The college’s curriculum was heavily influenced by British and European models, with a strong emphasis on draughtsmanship, perspective, and anatomical studies. Teachers were often recruited from overseas, bringing with them academic techniques and standards that helped elevate the quality of local art education.

One of the college’s most influential figures was Godfrey Rivers, an English-born artist who arrived in Brisbane in 1889. Rivers taught at the college and served as the honorary curator of the Queensland National Art Gallery. His dual role as educator and administrator allowed him to shape both the next generation of artists and the institutional direction of Queensland’s primary art collection. His own work, such as the well-known Under the Jacaranda (1903), painted in Brisbane’s Botanic Gardens, reflects a growing confidence in local subject matter and a stylistic shift toward impressionism.

The art produced in Brisbane during this time was varied but generally conservative by international standards. Portraiture, landscapes, and still-life remained the dominant genres, with artists often looking to the British Royal Academy for stylistic cues. Yet even within this framework, a distinctive local character began to emerge. Queensland’s subtropical light, open spaces, and unique flora provided a rich palette for artists willing to move beyond European models. The jacaranda tree, for example, became a visual emblem of Brisbane well before it was widely planted elsewhere in the country.

It was also during this period that the city’s first women artists began to gain recognition. While still working within the constraints of Victorian society, many women found in art a form of professional expression. Artists like Vida Lahey, though more prominent in the early 20th century, had their roots in the educational and social structures established during this era. Women were active in both the Queensland Art Society and the Technical College, often excelling in watercolour and illustration.

Importantly, the rise of art societies and schools also reflected broader shifts in Brisbane’s identity. No longer a penal colony or a rough outpost, the city was becoming a modern urban centre, keen to assert its cultural legitimacy. Art became one of the means through which it could project refinement, progress, and regional pride. Exhibitions were covered in local newspapers; artworks were purchased by public subscription; and artists were celebrated in civic events — all signs of a maturing cultural ecosystem.

By 1900, Brisbane had laid the groundwork for a sustained art tradition. It had established institutions, trained artists, formed networks of patronage, and begun to build a public collection. These developments were modest by international comparison, but they were deeply significant for Queensland. They signaled that Brisbane was no longer a passive recipient of cultural trends from Sydney or London, but a city ready to cultivate its own artistic identity.

The Federation Era and National Identity in Brisbane’s Art

The turn of the 20th century was a defining moment for Australia, politically and culturally. The six separate British colonies federated into a single nation in 1901, forming the Commonwealth of Australia. This political unification stirred a broader sense of national identity — a movement that resonated strongly in the visual arts. In Brisbane, as in other parts of the country, artists began to grapple with what it meant to depict not just a place, but a nation. The Federation era marked a shift in tone and ambition for Queensland artists, who now sought to define their work in relation to an emerging Australian identity, rather than simply echoing European traditions.

Brisbane’s artistic community, though still relatively small compared to Melbourne and Sydney, participated in this cultural redefinition with a distinctly local flavour. The Queensland Art Society continued to play a central role, holding regular exhibitions that emphasized scenes from everyday Australian life. There was a move away from romanticized European landscapes toward a focus on the unique character of the Australian bush, rural labor, and the subtropical environment of southeast Queensland.

A prominent figure of this era was Vida Lahey (1882–1968), whose artistic and educational work would come to define much of Queensland’s early 20th-century cultural output. Lahey studied at the Brisbane Technical College and later in Melbourne and Paris. Her works reflect a sensitive attention to domestic life and local scenery, often in watercolour — a medium suited to the bright, clean light of the region. She is perhaps best known for Monday Morning (1912), a painting that, while created later, exemplifies the Federation-era spirit in its dignified portrayal of working women. Lahey’s career also illustrates the increasing visibility and professionalism of women artists in Queensland, a shift that paralleled broader social changes following Federation.

Another significant artist was R. Godfrey Rivers, whose painting Under the Jacaranda (1903) became an icon of Brisbane’s visual identity. Though born in England, Rivers had by this time immersed himself in the Australian landscape, teaching and painting in Queensland for over a decade. His jacaranda scene, set in the Brisbane Botanic Gardens, exemplifies a quiet nationalism — not through grand historical subjects or political symbolism, but through a subtle embrace of local colour, climate, and setting. It captured a new civic pride, suggesting that Brisbane was not just a colonial settlement but a city with its own character, worthy of celebration in art.

The early 20th century also saw the expansion of the Queensland Art Gallery’s collection and public programming. Still housed in borrowed spaces, the gallery began acquiring more works by Australian artists, including those from Queensland. Though acquisition funds were limited, there was a growing awareness that a state art collection should reflect the region’s own landscapes, people, and aspirations. This period saw the purchase of works depicting rural life, Queensland flora, and coastal scenes — all reinforcing a sense of place within the national fabric.

Stylistically, the Federation era was transitional. Academic realism still dominated in Brisbane’s galleries and art schools, but newer influences — such as Impressionism and Symbolism — began to filter in through returning students and imported exhibitions. Artists began experimenting with looser brushwork, bolder colour palettes, and more personal responses to their surroundings. While Melbourne artists like Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts are often credited with pioneering the so-called “Australian Impressionism,” their impact was felt in Queensland too, where artists responded with interpretations shaped by their own environment.

Brisbane’s landscapes presented a challenge to those trying to emulate the golden hues of the southern bush. The subtropical light was sharper, the foliage denser, and the skies more humid and cloud-streaked. These differences forced Queensland painters to adjust their palettes and compositions, often producing works that stood apart from the national mainstream. Rather than eucalyptus blue and ochre, Brisbane’s artists turned toward greens, mauves, and the soft purples of flowering jacarandas.

Moreover, the Federation period encouraged a reconsideration of Aboriginal presence in the visual landscape. While mainstream depictions of Aboriginal people in art remained sentimental or ethnographic, there was a nascent interest in Aboriginal motifs and stories as symbols of a deeper, ancient connection to the land. This often occurred in problematic ways, as Aboriginal culture was appropriated without real understanding. However, the inclusion of Aboriginal figures or artefacts in Federation-era art also reflected a growing recognition — however superficial — that any true national identity would have to reckon with the continent’s original inhabitants.

In Brisbane, this reckoning was still largely symbolic. Few Aboriginal artists were visible in mainstream art circles at the time, and traditional Aboriginal art was rarely treated as “fine art” in gallery contexts. Nonetheless, Federation-era Brisbane set the stage for later generations to revisit and revise this history. The seeds of a more inclusive visual culture were being sown, even if they would not flower until much later.

Finally, the Federation era in Brisbane coincided with a broader cultural movement that valued civic beautification and national pride. Art was commissioned for public buildings, schools, and commemorative events. Sculptures and murals began to appear in parks and town halls, and artists were increasingly seen as part of public life — not just private creators. This civic role of art would become especially important in the interwar and post-war periods, as Brisbane’s population grew and its cultural ambitions expanded.

In summary, the Federation era marked Brisbane’s entry into the national artistic conversation. Its artists responded to the call for a uniquely Australian art with works grounded in local scenes, everyday life, and the character of Queensland’s environment. Though still navigating the tension between European training and local inspiration, they helped establish the visual vocabulary of Brisbane’s identity — one rooted in observation, climate, and a growing confidence in the region’s cultural value.

Interwar Artistic Developments and Modernist Experimentation

The period between the First and Second World Wars was a time of social transition and cultural testing in Brisbane, as it was across much of Australia. The trauma of the Great War, the shifting gender roles of the 1920s, and the economic hardship of the Depression years all left their mark on the city’s artistic scene. In this climate, Brisbane’s artists grappled with modernity — not only as a cultural force arriving from Europe and Sydney but also as a changing local reality. During the interwar years, Brisbane began to open itself, cautiously but deliberately, to modernist influences, even as traditional forms retained a strong foothold in its galleries and art schools.

At the core of this transitional period was a generation of artists trained in the classical techniques of realism and composition, but increasingly drawn to experimentation. Their exposure to modernist ideas came from several sources: returning expatriates who had studied abroad, national exhibitions of modern art, and a slowly expanding stream of international influence through books, journals, and visiting artists.

One key figure who bridged tradition and innovation was Daphne Mayo (1895–1982), Brisbane-born and internationally trained. Mayo was primarily a sculptor, and her work demonstrates both classical rigor and modernist boldness. After studying in London at the Royal Academy and working in France, she returned to Brisbane in the 1920s with a refined understanding of form and monumentality. Her 1930 commission — the tympanum above the entrance to Brisbane City Hall — is among the most significant public sculptures of the era. Though it draws on classical motifs, the scale, stylization, and civic prominence of the work placed modern Queensland art squarely in the public eye.

Mayo was also instrumental in promoting the arts more broadly. In 1929, she co-founded the Queensland Art Fund, an organisation dedicated to the purchase of artworks for the Queensland Art Gallery. This was a bold step in an era when arts funding was scarce and cultural institutions often lacked clear direction. Her efforts ensured that local collections began to reflect contemporary art trends, not just safe or traditional choices.

Brisbane’s painting scene during the interwar period remained dominated by the landscape and portraiture traditions, but there were undercurrents of change. Artists like Vida Lahey continued to produce technically accomplished works that reflected the quiet dignity of Australian domestic life. Yet younger painters began to turn their gaze outward — not just in terms of geography, but of form and intent.

One such artist was Lloyd Rees, who spent a formative part of his early career in Brisbane, having moved from Lismore. Although later more closely associated with Sydney, Rees’s early work was influenced by the Queensland landscape and light. His interest in architectural form and the spiritual qualities of landscape aligned him with certain aspects of European post-impressionism and romantic modernism.

Similarly, artists like William Bustard and Melville Haysom brought fresh energy to the local scene. Bustard, originally from England, settled in Brisbane in the 1920s and became known for his vibrant use of colour and bold compositions, particularly in stained glass and illustration. Haysom, on the other hand, was notable for his attempts to modernise the local art education system when he became head of the art department at Brisbane’s Central Technical College. He pushed for broader exposure to continental trends and encouraged students to engage with emerging styles.

Despite these sparks of modernism, Brisbane’s artistic institutions remained conservative. The Queensland Art Gallery, while slowly expanding its holdings, was not a driver of avant-garde taste. Its exhibitions during this period favoured traditional portraiture, academic landscapes, and safe thematic work. Brisbane’s relative geographic isolation and the tight social networks of its art scene made it difficult for radical new ideas to take root quickly.

Yet there were signs of a maturing cultural consciousness. The interwar period saw an increase in group exhibitions, public lectures on art, and critical reviews in the press. Newspapers like The Courier-Mail occasionally featured commentary on local exhibitions, reflecting a growing interest in the arts among Brisbane’s middle class. Art societies continued to play an important role, with the Royal Queensland Art Society (granted the “Royal” prefix in 1926) serving as both a platform for exhibiting artists and a conservative gatekeeper of taste.

Modernist experimentation often had to take place on the fringes. Small groups of artists formed informal collectives, hosted shows in alternative venues, and challenged the dominant aesthetic order in quiet ways. These pockets of creative resistance laid the groundwork for more visible modernist movements in the post-war era. Their legacy is not one of headline-grabbing manifestos or revolutionary breakthroughs, but of persistence — a slow and steady widening of what Brisbane art could be.

One cannot underestimate the importance of education in this transformation. Institutions like the Brisbane Central Technical College and The University of Queensland began offering more structured art programs, introducing students to art history and theory alongside practical instruction. Exposure to European and American modernist movements — Cubism, Expressionism, and Futurism — may have been filtered and academic, but it planted seeds for future development.

As the 1930s drew to a close and war loomed once again, Brisbane’s art scene was on the cusp of major change. A new generation, shaped by Depression-era austerity and global cultural upheaval, was beginning to question not only how art should look, but what role it should play in society. While still respectful of tradition, they sought to reflect modern life more directly — its speed, its dislocations, its fractured truths.

The interwar years in Brisbane were not defined by dramatic revolutions in style or ideology. Instead, they were marked by incremental shifts — the gradual infiltration of modernist thinking into a predominantly realist world. Artists began to push the boundaries of representation, experiment with form, and engage more consciously with international currents. The groundwork was being laid for the post-war boom in Queensland’s cultural life — a period when Brisbane would begin to assert itself not only as a regional centre, but as a contributor to the national and global art conversation.

The Role of the Queensland Art Gallery (Founded 1895)

The Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) stands as one of Brisbane’s cornerstone cultural institutions. Since its founding in 1895, the gallery has mirrored the city’s cultural evolution — from colonial outpost to a confident regional capital with a distinctive artistic voice. Though it began modestly and often struggled for funding and prominence in its early decades, QAG has gradually emerged as both a custodian of Queensland’s visual heritage and a leading national gallery. Its development is not only a chronicle of Brisbane’s art infrastructure but also a barometer of shifting tastes, public priorities, and institutional ambition.

The idea of a state art gallery in Queensland emerged out of the broader Federation-era movement to establish cultural institutions as markers of civic maturity. While cities like Melbourne and Sydney had already founded their public galleries by the 1860s and 1870s, Brisbane lagged behind, hindered by population size, budget constraints, and a less developed collecting culture. Nonetheless, in 1895, the Queensland National Art Gallery was officially founded, with its first home in the Brisbane Town Hall. Its creation was driven not by visionary curatorship, but by the practical desire to house a growing collection of works acquired through donations, state purchases, and prize exhibitions.

For its first half-century, the gallery’s role was modest. It operated in makeshift spaces — first at the Town Hall, then in the Exhibition Building in Bowen Hills, and later in the Queensland Museum. These locations were ill-suited to housing artworks properly, and the lack of a dedicated, purpose-built gallery reflected the ambivalence of successive governments toward cultural spending. Nonetheless, the gallery’s curators and supporters pressed on, slowly building a collection and lobbying for better facilities and recognition.

The collection during these early decades focused heavily on British and European academic art, reflecting both colonial tastes and the training of most local artists. Landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes dominated the walls, many purchased through the State Art Collection fund or acquired via the Royal Queensland Art Society. Notably, the gallery also acquired early works by local artists such as Godfrey Rivers and Vida Lahey, beginning the important (if slow) process of validating Queensland’s own artistic contributions within the state’s official narrative.

As the 20th century progressed, QAG’s role began to shift. A series of energetic curators, starting in the mid-century, expanded its focus to include more modernist and Australian works. The appointment of Bernard Smith and other progressive curators nationally helped set the tone for what galleries could be: not just repositories of inherited taste, but living institutions engaged in education, debate, and the promotion of new art. While Brisbane followed behind Melbourne and Sydney in this regard, its gallery nonetheless began to make bolder acquisitions and host more varied exhibitions.

A turning point came in 1975 with the opening of a new dedicated building for QAG in the Queensland Cultural Centre at South Bank, designed by Robin Gibson. This move — after decades of interim accommodations — was transformative. For the first time, Brisbane had a professional-grade space capable of housing major exhibitions, storing works in climate-controlled environments, and attracting international attention. The architecture of the new gallery, modernist in its design and strongly horizontal in orientation, reflected a confident, future-facing cultural outlook. It marked Brisbane’s arrival as a city that could not only produce art but also house and display it with authority.

This shift also marked the beginning of QAG’s expansion into the contemporary space. While the Queensland Art Gallery had long been a place to encounter art of the past — colonial portraiture, Federation landscapes, and the works of late 19th-century European painters — it now began collecting more experimental and modern works. Artists like William Robinson, Jon Molvig, and Ian Fairweather — all with Queensland connections — were given a place within the collection, alongside national and international figures.

By the 1980s and 1990s, QAG had grown into a major institutional player. The development of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT), launched in 1993, was among its most forward-thinking moves. Although the APT would ultimately become more closely associated with the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), it originated under QAG’s direction and signaled a new kind of curatorial ambition. The decision to focus on contemporary art from the Asia-Pacific region was both regionally strategic and intellectually prescient — acknowledging Brisbane’s proximity to and engagement with the broader Pacific world.

Throughout its history, QAG has also played a critical educational role. School programs, lecture series, and outreach initiatives have made the gallery a place of learning, not just looking. The gallery’s partnership with the Queensland Government and state schools has introduced generations of students to the visual arts, helping to seed a broader public interest in Brisbane’s artistic culture.

In terms of collecting, QAG has balanced its role as a national gallery with its responsibility to preserve and promote Queensland artists. This dual mission has shaped its acquisitions policy, which has consistently supported both well-known Australian names and artists with strong ties to the region. The gallery’s Queensland collection now spans from early colonial painters to contemporary Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal artists, reflecting the state’s complex and evolving identity.

QAG’s influence also extends beyond its walls. As the flagship gallery for Queensland, it has served as a mentor institution for regional galleries across the state — in Toowoomba, Cairns, Rockhampton, and elsewhere — providing loans, curatorial guidance, and touring exhibitions. This outreach has helped develop a cohesive, statewide visual arts culture, with Brisbane at its centre.

In sum, the Queensland Art Gallery has been more than just a museum of paintings. It has functioned as a civic mirror, reflecting Brisbane’s growth, tastes, and ambitions across more than a century. From its humble beginnings in borrowed rooms to its status today as a respected cultural institution, QAG has shaped — and been shaped by — the city around it. It is a testament to what long-term institutional commitment can achieve, even in a place once dismissed as peripheral to the national scene.

Brisbane in the Post-War Boom: Institutions, Infrastructure, and Individual Artists

The aftermath of World War II brought sweeping social and economic changes across Australia, and Brisbane was no exception. The post-war boom of the 1950s and 1960s, characterised by rapid urbanisation, rising living standards, and increased government investment in public infrastructure, created fertile ground for a cultural renaissance. While Sydney and Melbourne remained dominant in terms of population and art market influence, Brisbane — long viewed as conservative and slow-moving — began to assert a more confident and visible artistic identity. This momentum was powered by a mix of institutional development, rising public support, and the emergence of several highly influential individual artists who helped redefine what art in Queensland could be.

In terms of infrastructure, one of the most important legacies of the post-war period was the growing professionalisation of Brisbane’s cultural institutions. The Queensland Art Gallery, which had languished in borrowed and unsuitable spaces for decades, began to receive more sustained public funding. As plans were laid in the 1960s and 1970s for a permanent home in the Queensland Cultural Centre at South Bank, it became increasingly clear that the arts were being integrated into the vision of a modern Brisbane. The new gallery, which opened in 1982, would later become home to both QAG and, eventually, the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA). But its foundations were laid during the post-war period — in committee meetings, public campaigns, and government reports — all driven by a sense that the city deserved cultural infrastructure equal to its growing importance.

Beyond the gallery, other institutions also matured. The University of Queensland expanded its fine arts and art history programs, training a new generation of artists, curators, and scholars. The Queensland University of Technology (then the Queensland Institute of Technology) and the Brisbane Central Technical College also continued to play important roles in practical art education. These institutions, while differing in emphasis, all contributed to a deeper intellectual and technical base for visual culture in the city.

Artistically, Brisbane’s post-war scene saw a number of painters and sculptors gain national prominence. One of the most significant was Ian Fairweather (1891–1974), a reclusive and deeply original painter who settled on Bribie Island, just north of Brisbane, in the 1950s. Fairweather’s work fused Western modernism with Asian calligraphic and philosophical influences, creating a style that was entirely his own. Though he lived in relative isolation, his work was exhibited nationally and acquired by major galleries, helping to position Queensland — and Brisbane by proximity — as a site of serious artistic production. Fairweather’s legacy endures not only through his paintings but also through the mythos he created: the artist as a solitary thinker, in communion with nature, beyond the reach of metropolitan conformity.

Another major figure of the period was Jon Molvig (1923–1970), a painter whose expressive and psychologically charged works brought a raw energy to Brisbane’s art scene. Molvig moved to Brisbane in the 1950s and became a central figure in its creative community, teaching and mentoring younger artists while continuing to produce emotionally intense, often confronting paintings. His palette and brushwork were bold, and his subjects ranged from mythic allegories to introspective portraits. Molvig’s influence is difficult to overstate — he brought a seriousness and urgency to Queensland painting that reverberated through the next generation.

Among Molvig’s students was another seminal Brisbane artist: Ray Crooke. Although Crooke is best known for his tranquil depictions of life in northern Australia and the Torres Strait, he spent formative years in Brisbane and was part of the broader Queensland art world. His atmospheric, stylised canvases stood in contrast to the expressive force of Molvig’s work, offering a more contemplative approach rooted in place and people.

The period also saw the rise of William Robinson, a painter whose work — while more fully recognised in the 1980s and 1990s — had its origins in post-war Queensland. Robinson’s landscapes, with their multidimensional perspectives and deeply felt renderings of the southeast Queensland bush, reflect not only technical virtuosity but also a sustained engagement with environment and memory. His career would eventually cement him as one of Queensland’s most important contemporary artists.

What tied many of these artists together — despite stylistic differences — was a deep sense of regional connection. Unlike some of their southern contemporaries, who often pursued international recognition or relocated overseas, Brisbane’s post-war artists typically remained rooted in their state. This was not simply a matter of parochialism; it reflected a genuine belief that Queensland’s landscapes, people, and cultural conditions were worthy of serious artistic inquiry.

Meanwhile, artist-run initiatives and private galleries began to proliferate. Spaces such as the Johnstone Gallery (1950s–1970s), founded by Brian and Marjorie Johnstone, played a key role in exhibiting modern Australian artists and providing a venue for critical dialogue. The Johnstone Gallery’s exhibitions, held in a domestic setting in Bowen Hills, introduced Brisbane audiences to works by Russell Drysdale, Charles Blackman, and Sidney Nolan, among others. The gallery’s archives now reside with the State Library of Queensland, a testament to its lasting impact.

In addition to commercial galleries, Brisbane’s post-war decades saw an increase in government-sponsored public art. Sculpture and murals began to appear in civic spaces, schools, and government buildings, often created by artists trained in local institutions. These public commissions were part of a broader attempt to civilise the city’s image — to move it beyond its reputation as a hot, sprawling, provincial centre into something more cosmopolitan and cultured.

However, Brisbane’s post-war art scene was not without tensions. The city’s political climate remained relatively conservative throughout much of the 20th century, and censorship or institutional hesitation occasionally limited artistic freedom. Some artists found Brisbane’s cultural bureaucracy frustrating, especially compared to the more dynamic (and better-funded) environments of Sydney and Melbourne. Yet this adversity also fostered a sense of independence and camaraderie within Brisbane’s creative community. Artists, writers, musicians, and architects often worked together in small groups, sharing ideas and resources in a way that was both practical and creatively fertile.

In the final analysis, the post-war boom gave Brisbane the cultural scaffolding it had long lacked. Institutions were strengthened, artists emerged with distinct voices, and the infrastructure for exhibitions, education, and collecting improved dramatically. While still seen by some as peripheral, Brisbane had clearly entered a new phase — no longer content to imitate the art of other places, but beginning to speak with its own voice.

The 1980s Cultural Renaissance and Expo 88

The 1980s marked a defining cultural pivot for Brisbane. After decades of being perceived as a sleepy, conservative city — more associated with suburban sprawl and sweltering summers than with artistic experimentation — Brisbane began to shake off its provincial image. This transformation was driven by a unique convergence of political, economic, and civic forces that culminated in Expo 88, an international exposition that reshaped not just the South Bank precinct, but Brisbane’s cultural identity at large. During this period, the city underwent what can rightly be called a cultural renaissance, with long-term consequences for its artistic institutions, creative economy, and national reputation.

In the early part of the decade, Queensland was still under the long shadow of Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s administration (1968–1987), a government characterised by its pro-development stance and occasionally heavy-handed approach to civil liberties. Yet paradoxically, this same era saw increasing momentum in Brisbane’s cultural life. Artists, musicians, writers, and architects began to push back against conservative constraints with a newfound urgency. Alternative spaces emerged; university campuses and private homes became venues for avant-garde exhibitions, poetry readings, and political theatre. The underground scenes of Fortitude Valley and West End fostered a generation of creative thinkers who brought fresh energy to the city’s cultural bloodstream.

One of the most significant developments in institutional terms was the acceleration of arts infrastructure. The Queensland Art Gallery, which had moved into its purpose-built home at the Queensland Cultural Centre in 1982, began hosting larger, more ambitious exhibitions. No longer an under-resourced provincial gallery, QAG expanded its collection, hired more specialised staff, and pursued international partnerships. The establishment of the Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) in the early 1990s had its roots in this energetic period, reflecting an increasing awareness of Brisbane’s strategic position as a Pacific Rim city — a gateway to Asia rather than a satellite of Sydney.

But nothing transformed Brisbane more symbolically or physically than World Expo 88. Held between April and October 1988 to coincide with Australia’s bicentenary, Expo was ostensibly a celebration of international trade and technology. However, its impact on Brisbane’s visual and civic culture was profound. For six months, the city played host to 15 million visitors, who encountered not only global innovations but also a vastly reimagined urban landscape. The derelict industrial zone along the Brisbane River was reborn as South Bank — a vibrant cultural and recreational precinct that remains a defining feature of the city.

Art and design were central to Expo’s vision. Public sculptures, kinetic installations, and large-scale architectural statements filled the grounds. Australian artists were commissioned to produce site-specific works, and international contributors brought cutting-edge multimedia and conceptual art to Brisbane audiences. This exposure — often for the first time — to large-scale contemporary installations helped shift public expectations about what art could be, and where it could live. Art was no longer confined to galleries or institutions; it was integrated into the very fabric of the city.

Expo also influenced a generation of Queensland artists, some of whom participated directly, while others responded critically to its spectacle. While it brought international attention, some saw it as overly commercial, even kitsch — a polished facade that glossed over deeper social issues. Yet regardless of one’s perspective, Expo 88 forced a cultural reckoning. It raised questions about who Brisbane was, what kind of city it wanted to be, and what role culture should play in shaping that identity.

Meanwhile, a host of smaller but vital developments deepened the city’s artistic ecosystem. The Institute of Modern Art (IMA), established in 1975 but particularly active in the 1980s, offered an independent platform for experimental and contemporary work. Located in the Valley, and later in Fortitude Valley’s Judith Wright Centre, the IMA became a critical space for artists working outside traditional modes — from performance art to video installations. Unlike more conservative institutions, the IMA encouraged risk-taking and dialogue, often exhibiting artists before they gained mainstream recognition.

At the same time, tertiary institutions strengthened their creative programs. The Queensland College of Art, part of Griffith University by the 1990s, expanded its facilities and course offerings, nurturing students in both fine arts and design. University-affiliated galleries such as UQ Art Museum also began to assert curatorial independence, offering academic rigor alongside public programming. These institutions, though less visible than Expo, played an essential role in forming the city’s intellectual and aesthetic foundations.

Artist-run initiatives also flourished during the 1980s. Collectives like THAT Contemporary Art Space, the Brisbane Artist Run Initiative (BARI), and Doggett Street Studios emerged to fill gaps in exhibition opportunities and to foster community among emerging artists. These spaces offered not only physical venues for exhibitions, but also a spirit of DIY autonomy that countered institutional hierarchies. The cross-pollination of painters, sculptors, musicians, and writers during this period laid the groundwork for Brisbane’s now-celebrated creative precincts.

The 1980s also saw a generational shift in aesthetic sensibility. While many artists still engaged with traditional media, there was a growing embrace of installation, conceptualism, photography, and new media. Some began to incorporate Queensland’s unique environment — its light, humidity, and flora — into their work in more abstract ways. Others tackled political and social themes, including urban sprawl, Aboriginal rights, and gender dynamics, although often through oblique or allegorical means rather than overt activism.

Brisbane’s identity during this decade was thus marked by contradiction: conservative governance alongside radical art; suburban monotony countered by bursts of creative energy; and civic boosterism tempered by underground critique. This friction proved fertile. It pushed artists to innovate, to define themselves against a dominant narrative, and ultimately, to help reimagine what Brisbane could be.

By the end of the 1980s, the transformation was undeniable. Brisbane was no longer simply the administrative centre of Queensland. It had become a city of ideas — a place where culture was not just consumed, but created. The seeds planted during this decade would flower in the 1990s and beyond, especially with the founding of GOMA and the international expansion of the Asia Pacific Triennial.

The Founding and Impact of the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA)

When the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) opened its doors in December 2006, it marked a major cultural milestone not just for Brisbane, but for Australia as a whole. Located on the banks of the Brisbane River within the Queensland Cultural Centre precinct at South Bank, GOMA was envisioned as a bold architectural and curatorial statement — a world-class venue for contemporary art in a city still shaking off its old reputation as culturally conservative. Its founding was the culmination of decades of incremental growth, but it also signalled a radical new phase in Brisbane’s art history: a period defined by confidence, global reach, and institutional ambition.

Designed by Architectus Brisbane under the leadership of Kerry Clare, Lindsay Clare, and James Jones, the building itself made a striking impression. Unlike traditional museum architecture — often formal, symmetrical, and classically inspired — GOMA embraced an open, light-filled, and modernist sensibility that mirrored the art it intended to showcase. Its vast galleries, adaptable spaces, and integration with the river and surrounding parklands created a venue as inviting as it was innovative. It was a deliberate signal that Brisbane was ready to take its place on the world stage of contemporary visual culture.

While the Queensland Art Gallery had long collected and exhibited contemporary art, the creation of a dedicated modern art museum gave curators far greater freedom to experiment. GOMA’s opening exhibition featured an ambitious selection of new media, installation art, large-scale painting, and international commissions. Its program was unapologetically global in scope — but also locally attuned, reflecting Queensland’s distinct environment and cultural mix.

What immediately distinguished GOMA from other state galleries was its strong focus on the Asia Pacific region. Building on the success of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT), which had begun under QAG in 1993, GOMA positioned itself as a centre for art from countries often overlooked in Western museum narratives: Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, India, the Pacific Islands, Korea, Thailand, and beyond. This curatorial direction was not just a matter of geography, but of philosophy. It reflected Brisbane’s role as a Pacific city — not just a regional Australian capital — and one that could offer alternative perspectives on global contemporary art.

The Asia Pacific Triennial became GOMA’s signature exhibition series, growing in scale, sophistication, and international visibility with each iteration. Unlike many large-scale art biennials and festivals, the APT did not parachute in foreign artists for short-term shows. Instead, it cultivated long-term relationships with artists, curators, and communities across the region. This made the exhibitions feel more organic and respectful, offering audiences insight into complex cultural contexts rather than surface-level spectacle.

In addition to its regional focus, GOMA has also embraced emerging media. From its inception, the gallery has made serious commitments to video art, digital installations, film, and interactive experiences — recognising that contemporary art is not limited to traditional formats. Its purpose-built cinema, which screens international film festivals and artist retrospectives, has expanded the definition of what a visual art institution can be. GOMA was one of the first major Australian galleries to treat moving image and new media as core parts of its curatorial program, not side attractions.

Local artists, too, have benefited from GOMA’s presence. The gallery has consistently supported Queensland-based practitioners through acquisitions, commissions, and solo exhibitions. Artists such as Judy Watson, Vernon Ah Kee, and Richard Bell — each with deep Queensland connections — have received international exposure in part due to their inclusion in GOMA’s exhibitions and collections. This support has been particularly important for Aboriginal artists, whose work is now presented not as ethnographic curiosity, but as vital contemporary commentary.

GOMA’s impact extends beyond exhibitions and acquisitions. It has become a central node in Brisbane’s creative economy — a magnet for tourism, a stimulus for public art, and a partner for education at all levels. School tours, artist talks, residencies, and festivals have turned the gallery into a living, breathing civic space, not just a repository of objects. Unlike earlier periods when art in Brisbane felt somewhat detached from everyday life, GOMA has helped embed culture into the urban fabric.

Perhaps most significantly, GOMA has helped change how Brisbane sees itself. Once considered culturally marginal, the city now hosts one of the most visited and respected contemporary art museums in the southern hemisphere. The gallery has proven that Brisbane audiences are not only receptive to complex, challenging, or global art — they welcome it. Attendance figures consistently exceed expectations, and GOMA’s reputation among international curators and artists continues to grow.

The ripple effects of GOMA’s success can be felt across the city. Fortitude Valley, West End, and South Brisbane have seen an increase in artist-run spaces, pop-up exhibitions, and design studios. Public art is more visible than ever, and city planners now include cultural precincts in their urban strategies. Events like Brisbane Festival, the Queensland Poetry Festival, and the World Science Festival have found visual art to be a natural collaborator. In short, GOMA has not only elevated the city’s global standing — it has reshaped the role of visual culture within Brisbane itself.

While the long-term sustainability of any institution depends on leadership, funding, and public engagement, GOMA has so far succeeded where many others have faltered: it has remained bold without becoming alienating, accessible without sacrificing ambition, and rooted in place while reaching far beyond it.

Brisbane’s Place in Contemporary Australian Art

Brisbane’s trajectory within the broader landscape of Australian art has often been one of quiet ascendance. Long overshadowed by the dominance of Sydney’s commercial art scene and Melbourne’s intellectual weight, Brisbane carved a different path — one grounded in regional distinctiveness, institutional evolution, and the cultivation of artistic voices that resonate both nationally and internationally. In the contemporary moment, Brisbane can no longer be seen as peripheral. It is a city with its own artistic gravity, contributing meaningfully to the diversity and dynamism of Australian art.

One of the most defining features of Brisbane’s contemporary art scene is its strong regional identity. This is not expressed through provincialism or aesthetic uniformity, but through a persistent connection to place — to climate, light, land, and community. Artists in Brisbane have often drawn inspiration from the subtropical environment, from the socio-political history of Queensland, and from the cultural dialogues that arise in a city located more closely to Asia and the Pacific than to the centres of southern Australia. This has produced work that is visually distinct and often more globally attuned than might be expected from a city of its size.

Contemporary Aboriginal art is a particularly important component of Brisbane’s contribution. The city is home to a number of significant Aboriginal artists whose work challenges and expands the national narrative. Vernon Ah Kee, a member of the Kuku Yalanji, Waanji, Yidinji, and Gugu Yimithirr peoples, creates sharp, confrontational works that explore race, history, and the legacy of colonialism. His text-based pieces, drawings, and video installations have been exhibited internationally and collected widely, yet they remain grounded in the lived reality of Aboriginal experience in contemporary Australia.

Similarly, Judy Watson — a Waanyi artist born in Mundubbera, Queensland, and long associated with Brisbane — has created a body of work that merges political memory with lyrical abstraction. Her installations and mixed-media works address institutional histories, land, and loss, often using materials such as ochre, rust, and natural dyes to evoke the physical and spiritual traces of the past. Watson’s art balances delicacy and gravity, placing her among the country’s most important voices in both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal contexts.

Beyond the sphere of Aboriginal art, Brisbane has produced painters like William Robinson, whose lush, multidimensional landscapes continue to influence younger generations, and Gordon Bennett (1955–2014), whose work explored the complexities of postcolonial identity through a mix of figuration, abstraction, and historical symbolism. Bennett, though born in Monto and based in Brisbane, developed a national reputation, exhibiting widely and influencing discourse around race, history, and representation in Australian art.

In terms of infrastructure, Brisbane now boasts an enviable network of institutions. GOMA and QAG provide flagship platforms for major exhibitions and collections. The Institute of Modern Art (IMA) continues to be one of Australia’s most important venues for experimental and international contemporary art, often debuting ambitious projects by artists from Australia and abroad. University galleries such as Griffith University Art Museum and the UQ Art Museum support rigorous curatorial work and foster dialogue between academic research and visual practice.

Commercial galleries have also matured, with spaces like Jan Manton Art, Milani Gallery, and Edwina Corlette Gallery representing high-calibre artists and maintaining an active presence in the national art market. While Brisbane may not yet rival Sydney in terms of commercial sales volume, its gallery ecosystem is increasingly professional and respected.

Equally important are the grassroots initiatives and artist-run spaces that continue to underpin Brisbane’s creative community. Outer Space, Boxcopy, and Wreckers Artspace are just a few examples of the many venues that provide vital support for emerging artists, experimental work, and community engagement. These spaces serve as laboratories — places where new ideas are tested and where risk is not only tolerated but encouraged.

Education remains a key driver of the city’s contemporary art landscape. Griffith University’s Queensland College of Art (QCA), Queensland University of Technology (QUT), and the University of Queensland all offer robust programs in visual arts, art history, and curatorship. These institutions feed into the professional world, providing artists, educators, and arts workers with the training and networks needed to sustain creative careers. The presence of multiple university galleries also supports critical discourse and curatorial development.

Culturally, Brisbane occupies a unique space within the Australian imagination. It is viewed as youthful, climate-conscious, and culturally hybrid — a city with a strong local identity but an increasingly international outlook. Its population growth, driven by migration from both interstate and overseas, has brought with it new perspectives and demands for cultural engagement. Brisbane artists today are just as likely to reference Pacific diasporas, climate change, and border politics as they are to reflect on suburban life or landscape traditions.

Festivals and biennials have also played a role in projecting Brisbane’s artistic voice beyond its borders. The Asia Pacific Triennial remains the flagship event, but Brisbane Festival, Metro Arts’ programming, and events like the Brisbane Portrait Prize have expanded the city’s cultural calendar. These events provide not just spectacle, but platforms for serious dialogue, experimentation, and collaboration.

The city’s geographic and climatic conditions have even influenced new media and design practices. Brisbane’s architecture and design sectors are increasingly interested in sustainability, local materials, and place-responsive aesthetics — concerns that are reflected in visual art through installations that use found objects, biodegradable materials, and participatory structures. Artists are creating works that speak directly to Queensland’s environmental challenges, from drought and flooding to biodiversity loss.

In terms of national recognition, Brisbane artists are now regularly shortlisted for and win prestigious prizes such as the Archibald, Wynne, and Sulman, as well as the Ramsay Art Prize and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards. Brisbane is no longer a feeder city for Sydney or Melbourne; it is a destination in its own right — a place where artists can live, work, and exhibit without having to relocate to make their mark.

If the 20th century saw Brisbane striving for cultural legitimacy, the 21st has seen it claiming it. What defines the city now is not a need to emulate other centres, but a commitment to its own character — a combination of regional rootedness, institutional confidence, and global engagement.

Art Festivals, Public Art, and the City’s Urban Aesthetic

As Brisbane entered the 21st century, its visual culture began to extend beyond gallery walls, spilling into the streets, laneways, and public squares. The city’s aesthetic identity became increasingly defined not only by its institutions and artists, but also by the ways art intersected with public life — through festivals, permanent installations, and urban design. This evolving relationship between art and city space has played a major role in reshaping Brisbane’s civic image, making it a more vibrant, expressive, and culturally integrated urban environment.

Brisbane’s festival culture has been instrumental in expanding access to and engagement with visual art. The Brisbane Festival, relaunched in its current form in 2009, is a flagship example. While it incorporates music, theatre, and performance, the visual arts remain central — through public installations, large-scale projections, and artist collaborations that transform the cityscape. The festival’s integration of art into public space helps bring contemporary visual language to audiences who might never step into a gallery. Whether through light installations along the river or interactive sculptures in city parks, the Brisbane Festival makes art a civic experience.

A key component of this public-facing approach is the Brisbane Street Art Festival (BSAF), which has grown rapidly since its inception in 2016. Unlike traditional graffiti events or ephemeral art jams, BSAF has helped legitimize and elevate street art in Brisbane. It has also redefined expectations for what “public art” can look like. International and local artists alike have participated in large mural commissions that now grace buildings across Fortitude Valley, South Brisbane, and Woolloongabba. These works, often vibrant and ambitious in scale, reflect a broad mix of cultural influences and techniques, ranging from photorealism to abstract expressionism.

One particularly influential site is the Howard Smith Wharves, a riverside redevelopment that incorporates not just dining and event spaces, but also a curated public art program. Alongside architectural preservation and landscaping, the area includes contemporary sculptures and installations that reflect Brisbane’s mix of heritage and modernity. Other precincts, such as the Fish Lane Arts Precinct in South Brisbane, have also embraced visual culture as a driver of urban renewal, using art to anchor hospitality, retail, and tourism in a deeper sense of place.

Permanent public art has likewise become part of the city’s identity. Queensland’s Art in Public Places program, administered through Arts Queensland, has supported the commissioning of sculptures and installations across the state. In Brisbane, this has resulted in a wide variety of works — from large bronze commemorative statues to experimental pieces in unexpected locations. Notable installations include Clement Meadmore’s “Open Form” at the Queensland Art Gallery, Donna Marcus’s “Steam” in the South Bank Parklands, and Sebastian Di Mauro’s “Green Room” in Brisbane Square. These works help anchor contemporary art in everyday environments, encouraging chance encounters and informal reflection.

Another important facet of Brisbane’s public art evolution is its commitment to Aboriginal cultural visibility. Projects like The Edge (a digital culture centre adjacent to the State Library) and GOMA’s “Maiwar” program, which commissions temporary artworks by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists, ensure that First Nations voices remain part of the city’s visual narrative. These installations often incorporate Aboriginal languages, materials, and stories into their forms, embedding cultural memory into the urban grid.

Meanwhile, ephemeral works — those designed to last days or weeks — have become common features in Brisbane’s cultural calendar. From light installations during the Brisbane Festival, to sculptural performances at Metro Arts, to temporary installations on the lawns of QAGOMA, these works play a critical role in testing public engagement with experimental formats. Ephemerality also encourages risk-taking: artists can push boundaries without the burden of permanence, and audiences can experience the city anew with each iteration.

Civic commissions and urban planning strategies have increasingly embraced art as place-making. City-led design frameworks now integrate public art into infrastructure projects, from pedestrian bridges to transit hubs. The Kurilpa Bridge, for instance, while a piece of engineering, is also a sculptural element within the city’s skyline — its elegant, spoked design intentionally drawing visual parallels to Brisbane’s maritime and Aboriginal heritage. Similarly, the Victoria Bridge renewal project has included commissioned artworks as part of its broader urban design goals, reinforcing Brisbane’s commitment to art as a public good.

Art festivals, meanwhile, continue to push the boundaries of audience experience. Events like Anywhere Festival, which stages performances and installations in non-traditional venues (from car parks to lounge rooms), and the World Science Festival Brisbane, which often incorporates visual artists into its programming, challenge the definition of what constitutes an art space. This decentralisation of culture has helped democratise Brisbane’s art scene, making it more accessible and less dependent on formal institutions.

The economic benefits of this visual turn are also noteworthy. Public art and festivals have contributed to the revitalisation of inner-city precincts, the growth of creative industries, and the expansion of cultural tourism. Importantly, Brisbane has embraced this development without over-commercialising it. While there is sponsorship and branding, the art remains central — a sign that Brisbane’s leadership has begun to understand cultural capital not merely as ornament, but as infrastructure.

Finally, it’s worth noting that Brisbane’s climate has shaped its urban aesthetic. Outdoor artworks must contend with heat, rain, and humidity, which has pushed many artists and designers toward robust materials like stainless steel, ceramic, and UV-resistant paints. It has also led to a preference for open-air experiences: sculpture trails, mural walks, and festival routes that encourage movement and interaction. This physicality — this tactile, weather-conscious engagement — is part of what makes Brisbane’s public art distinct.

In the end, Brisbane’s urban aesthetic today is inseparable from its visual culture. Art is not just something to be consumed indoors, but something that defines and enlivens the city itself. From laneway murals and festival installations to commemorative sculptures and digital projections, the city has become a living gallery — dynamic, diverse, and unmistakably Brisbane.

Conclusion: Continuity, Identity, and the Future of Brisbane’s Art Scene

Brisbane’s art history is not a simple tale of linear progress or sudden transformation. It is a layered narrative — built across centuries, shaped by geography, institution, community, and conviction. From the enduring visual culture of the Turrbal and Jagera peoples, to the sketchbooks of colonial surveyors, to the expressive turbulence of post-war painters and the institutional ambition of GOMA, Brisbane’s identity as an art city has been forged through persistence and reinvention.

What emerges most clearly from this history is a sense of continuity grounded in place. Artists in Brisbane — regardless of style, era, or medium — have consistently responded to their environment. The city’s subtropical light, its riverine geography, its cycles of flood and bloom, and its relative distance from the artistic centres of the south have all contributed to a distinct visual sensibility. Brisbane has always looked outward — toward Asia, the Pacific, and the wider world — but it has done so with its feet firmly planted in the red earth and winding banks of Queensland.

Institutionally, Brisbane’s art ecosystem is now among the most robust in the country. The dual engines of QAG and GOMA provide a foundation of curatorial depth and international engagement, while artist-run spaces and educational institutions ensure that risk, experimentation, and renewal remain part of the equation. The Asia Pacific Triennial has placed Brisbane on the global contemporary art map, while public art programs and festivals have made visual culture a civic priority.

Brisbane’s success lies in its refusal to merely copy other models. It did not become Melbourne. It did not try to outpace Sydney. Instead, it became itself — a city where art is intimate as well as expansive, public as well as personal, and shaped by both the past and the pressure of the present.