William Morris, born on March 24, 1834, in Walthamstow, England, emerged as a multifaceted force in the 19th-century arts and crafts movement. A visionary designer, poet, and social activist, Morris played a pivotal role in reviving traditional craftsmanship and promoting a holistic approach to art. His life’s journey unfolded during a period of industrialization and social change, shaping his commitment to the ideals of beauty, craftsmanship, and social justice.

Early Artistic Ambitions

From an early age, Morris displayed a keen interest in the arts. His family’s wealth provided him the opportunity to explore his creative inclinations, and he attended Marlborough College and later Exeter College, Oxford. At Oxford, Morris formed lasting friendships with fellow artists and thinkers, including Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who shared his passion for a return to medieval craftsmanship and aesthetic principles.

Following university, Morris joined the architectural firm of George Edmund Street. However, his desire to engage with the artistic process more directly led him to pursue a career as a painter. Morris’ early artistic ambitions were influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group that sought to revive the aesthetic principles of medieval art, emphasizing detailed craftsmanship and vibrant color.

The Red House and the Birth of Morris & Co.

In 1859, Morris embarked on a significant chapter of his life by commissioning the construction of the Red House in Bexleyheath. Designed by architect Philip Webb, the Red House became a manifestation of Morris’ vision for a total work of art, where architecture, decoration, and furnishings harmonized seamlessly. This endeavor marked the beginning of Morris’ exploration into the integration of art and daily life.

Inspired by the collaborative spirit of the Red House project, Morris co-founded the design firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. in 1861. The firm, later known as Morris & Co., brought together a group of talented artists and craftsmen, including Burne-Jones and Rossetti. Their collective aim was to produce exquisite decorative arts that adhered to the principles of medieval craftsmanship while embracing the opportunities afforded by contemporary technologies.

Textiles and Wallpaper Revolution

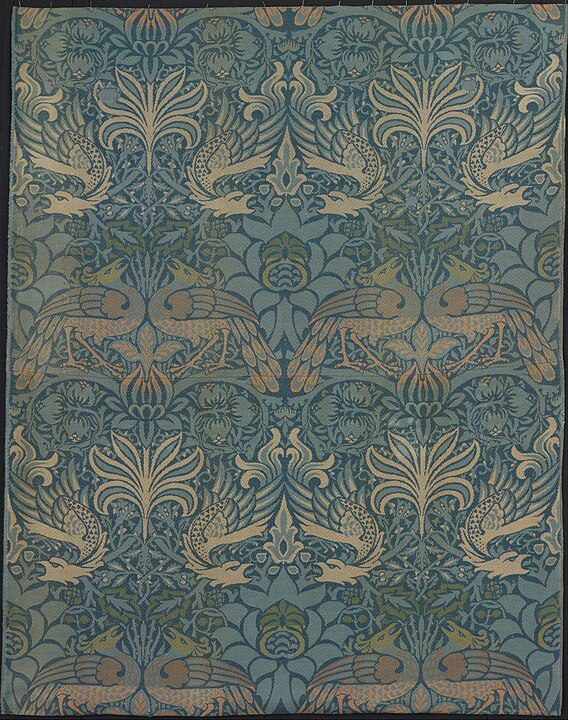

One of Morris’ enduring contributions to the arts and crafts movement was his revolutionary approach to textiles and wallpaper design. Disheartened by the poor quality and tasteless designs of mass-produced goods, Morris sought to redefine the textile industry. He envisioned a return to handcrafted excellence, emphasizing intricate patterns and natural dyes inspired by medieval tapestries and illuminated manuscripts.

Morris & Co. quickly gained renown for its exquisite textiles, wallpapers, and carpets. Morris’ designs, characterized by intricate floral patterns and rich colors, became synonymous with the Arts and Crafts aesthetic. His commitment to high-quality craftsmanship and the use of traditional techniques set a standard that inspired generations of designers and artisans.

Socialist Ideals and Political Engagement

While Morris achieved success as a designer and entrepreneur, his commitment to social justice led him to engage actively in political activism. Influenced by socialist ideals, Morris joined the Social Democratic Federation and later the Socialist League. He advocated for workers’ rights, fair wages, and the abolishment of the capitalist system. Morris believed that the alienation caused by industrialization could be remedied through a return to handcraftsmanship and a more equitable distribution of wealth.

As a prolific writer and speaker, Morris used his platform to disseminate his socialist beliefs. His influential essays, such as “Art and Socialism” and “Useful Work versus Useless Toil,” articulated his vision for a society where art, work, and daily life were integrated harmoniously. Morris’ dual role as an artist and socialist made him a unique figure, bridging the realms of aesthetics and social reform.

Kelmscott Press and the Revival of Printing

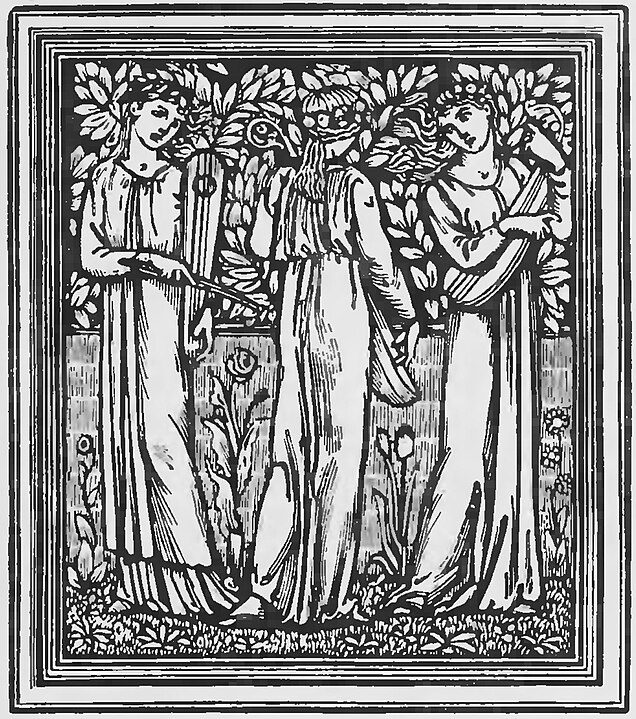

In the final chapter of his career, Morris turned his attention to the art of printing and book design. In 1891, he established the Kelmscott Press, named after his country home in Oxfordshire. The press aimed to revive the art of printing, emphasizing traditional craftsmanship and rejecting the mechanized processes of contemporary publishing.

Under Morris’ meticulous guidance, the Kelmscott Press produced a series of masterfully crafted books, including the iconic “Kelmscott Chaucer.” Morris designed typefaces, borders, and illustrations, ensuring each book was a work of art in its own right. The Kelmscott Press became a symbol of the Arts and Crafts movement’s commitment to the revival of medieval craftsmanship and the creation of beautiful, functional objects.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

William Morris’ legacy endures through the lasting impact of his ideas on design, craftsmanship, and social reform. His vision for the integration of art and daily life influenced subsequent design movements, including the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements. Morris’ call for a return to handcraftsmanship and the rejection of mass production echoed in the ethos of the Arts and Crafts movement, leaving an indelible mark on design philosophy.

Beyond the realm of design, Morris’ socialist ideals and activism also left a profound legacy. His writings continue to be studied and referenced in discussions about the relationship between art, society, and labor. Morris’ influence extended far beyond his lifetime, shaping the trajectory of design, printing, and social thought in the 20th century and beyond.

Later Years and Reflection

In the later years of his life, Morris continued to balance his creative pursuits with his political convictions. Despite facing health challenges, he remained active in both the Kelmscott Press and political activism. Morris’ commitment to his ideals persisted until his death on October 3, 1896.

William Morris’ remarkable journey—from the early Pre-Raphaelite inspirations to the establishment of Morris & Co., the Kelmscott Press, and his tireless advocacy for social change—left an indelible imprint on the arts and crafts movement. His legacy extends beyond the tangible beauty of his designs to the enduring principles that emphasize the intrinsic value of craftsmanship, the marriage of art and life, and the pursuit of a more just and equitable society.