Thomas Moran was born on February 12, 1837, in Bolton, Lancashire, England. His family, facing economic hardships due to the Industrial Revolution, emigrated to the United States in 1844. They settled in Philadelphia, where the art scene offered opportunities for young, aspiring artists. Surrounded by craftspeople and painters, Moran found early inspiration in this culturally rich environment.

Moran’s older brother, Edward Moran, was already establishing himself as a marine painter and served as a mentor to Thomas. At age sixteen, Thomas began an apprenticeship with the Philadelphia engraving firm Scattergood & Telfer. There, he honed his skills in engraving and drawing, which gave him the technical foundation for his later work. Although trained as an engraver, Moran was more passionate about painting landscapes.

During these years, he began to study the works of J.M.W. Turner, the English Romantic master known for his dramatic use of light and color. Moran pored over reproductions of Turner’s art, absorbing his use of atmosphere and expressive color. This influence would remain with him throughout his life, though he adapted it to the unique American terrain he would come to portray.

Moran did not attend any formal art academy, but his self-guided studies, apprenticeships, and field experience shaped his development. Philadelphia’s thriving artistic community offered exposure to a wide range of styles and disciplines. By the end of the 1850s, Moran had begun to exhibit his work and was making a name for himself as a skilled landscape artist. His journey westward was still to come, but his foundation was already firmly laid.

Finding His Artistic Identity

During the 1860s, Moran refined his approach and developed a style that would set him apart from his contemporaries. His landscapes of the Eastern United States, particularly scenes from Pennsylvania and New Jersey, showed an eye for detail and an emotional interpretation of nature. These early works hinted at the grandeur he would later bring to the American West. Even then, critics noted the atmospheric quality of his painting, influenced by the Romantic movement.

Moran also worked extensively as an illustrator, contributing to magazines and books. His illustrations helped sharpen his sense of composition and storytelling. He became known for his ability to turn field sketches into compelling visual narratives. This period was crucial in merging his technical background with his emerging artistic vision.

Turner’s Shadow and Moran’s Emerging Style

In 1863, Thomas Moran married Mary Nimmo, a Scottish-born artist and skilled etcher. Their marriage was both a romantic and professional partnership. Mary supported her husband’s career and produced impressive works of her own, often focused on landscapes and rural scenes. Together, they created a home life rooted in creativity and collaboration.

Moran’s growing body of work drew comparisons to J.M.W. Turner, earning him the nickname “the American Turner.” However, Moran insisted on developing his own voice, using Turner’s influence as a foundation rather than a formula. His use of vibrant color, glowing light, and sweeping vistas evolved into something uniquely suited to the American landscape. By the late 1860s, he had begun contemplating a journey into the uncharted territories of the West.

The Yellowstone Expedition and National Fame

In 1871, Moran seized the opportunity that would define his career: an invitation to join the U.S. Geological Survey expedition to Yellowstone. Led by Ferdinand V. Hayden, this journey aimed to document the region’s geography and assess its potential for preservation. Moran, along with photographer William Henry Jackson, played a key role in visually capturing the landscapes. It was Moran’s first time in the West, and the scenery stunned him.

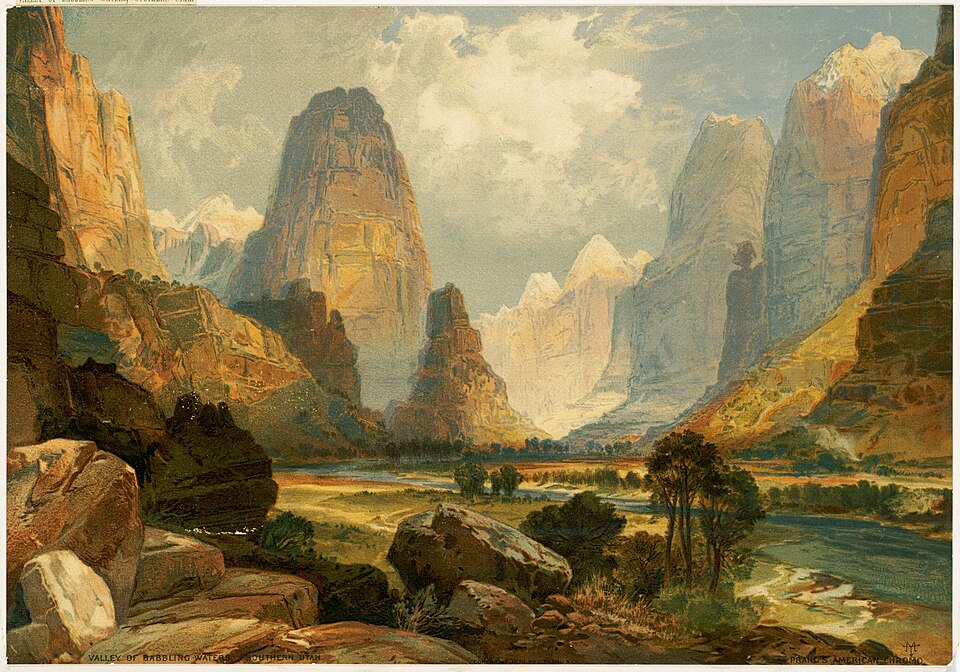

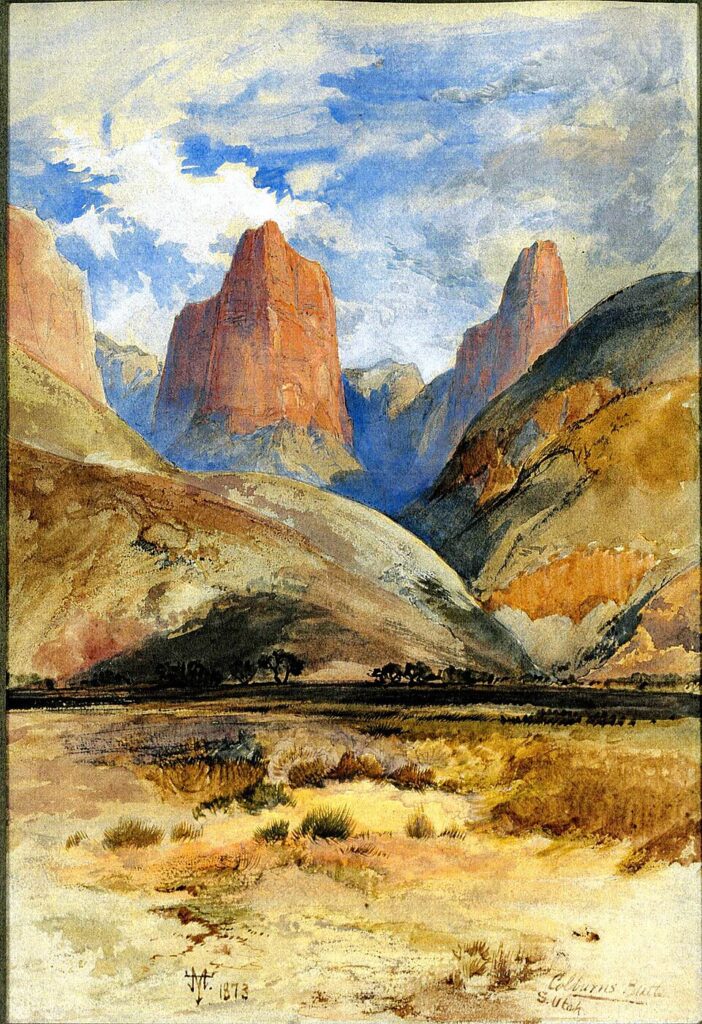

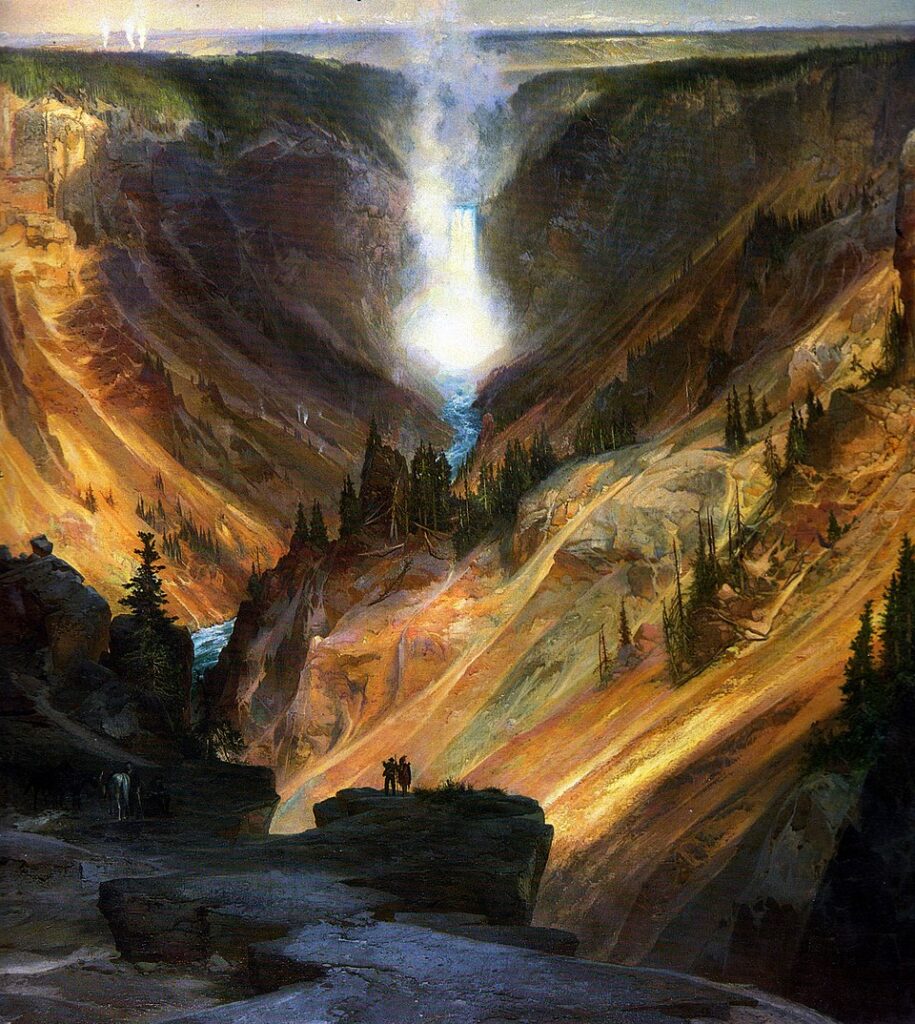

The expedition took place between July and August 1871. During that time, Moran created dozens of field sketches, watercolors, and journal notes. His observations later served as the basis for finished paintings that captured the grandeur of Yellowstone. The most famous of these was “The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone,” completed in 1872.

Moran and the Hayden Survey of 1871

That painting was purchased by the U.S. Congress for $10,000—a substantial sum at the time. It became part of the Capitol’s art collection, solidifying Moran’s national reputation. More importantly, the painting was used to help persuade Congress to establish Yellowstone as the first national park in 1872. Moran’s work, paired with Jackson’s photographs, offered compelling visual proof of the area’s unique beauty.

Moran’s images were not just works of art—they were instruments of persuasion. His portrayal of the West was grand, almost biblical in scope, and appealed to both scientific and emotional arguments for preservation. After Yellowstone, Moran would continue to travel and paint the great natural wonders of the American frontier. His work helped shape a public image of the West that persists to this day.

Exploration of the American West

After Yellowstone, Moran continued exploring the West, drawn by its vast, untouched beauty. In 1873, he joined the expedition led by John Wesley Powell to the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River. This journey added another iconic landscape to Moran’s portfolio. His painting “The Chasm of the Colorado” became another masterpiece tied to America’s growing appreciation for its western lands.

These trips were grueling and required considerable physical endurance. Moran, however, was undeterred. He saw these expeditions as both artistic missions and patriotic endeavors. His sketches often combined on-site accuracy with imaginative reconstruction in the studio.

From Yellowstone to the Grand Canyon

Moran’s paintings from these journeys included depictions of Zion Canyon, Yosemite, the Tetons, and more. Each canvas amplified the majesty of the American wilderness. His representations were not just records of place—they were expressions of awe, designed to inspire and uplift. Through his paintings, he conveyed a vision of nature as a national treasure.

As his fame grew, reproductions of Moran’s work were widely distributed through engravings and lithographs. His images appeared in publications, public exhibitions, and even government buildings. He became a visual ambassador for the American landscape, shaping public perception of the West for generations. His blend of romanticism and realism made him a favorite among collectors and institutions alike.

Style, Technique, and Artistic Legacy

Moran’s work stood out for its luminous color palettes, dramatic lighting, and sweeping compositions. His style combined the grandeur of European Romanticism with the rugged specificity of American scenery. This made his landscapes emotionally powerful and topographically convincing. He knew how to use scale to overwhelm the viewer—in the best sense.

He frequently began with field sketches and watercolor studies, later transforming them into large oil paintings in his studio. This approach gave his finished works both immediacy and polish. He paid attention to geological detail while emphasizing light and atmosphere. This method set him apart from artists who either leaned too heavily on science or on sentimentality.

The “American Turner” and Master of the Sublime

The nickname “TYM”—Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran—emerged as a tribute to his role in American conservation and culture. His Yellowstone paintings were more than artistic milestones; they were national symbols. The initials “TYM” became a kind of personal brand, stamped on his later works. He saw himself as both an artist and a chronicler of divine creation.

Moran’s legacy lives on in how Americans view their natural heritage. He inspired later landscape painters, park advocates, and photographers. His fusion of the sublime with national pride helped forge an artistic identity that was distinctly American. Few artists have shaped public imagination with such enduring power.

Later Years and Continued Recognition

In his later years, Moran settled in East Hampton, New York, where he continued to paint until his death. His studio, built in 1884, remains preserved today as a historical site. Moran lived a long and productive life, dying on August 25, 1926, at the age of 89. His career had spanned more than six decades.

Even in old age, Moran remained active, producing new works and exhibiting frequently. He adapted to changing tastes while maintaining the grandeur of his earlier pieces. Collectors and institutions continued to seek out his art. His images remained timeless, grounded in a vision of natural beauty.

A Long Career and National Honors

Moran’s work entered the collections of major museums, including the Smithsonian and the National Gallery of Art. His legacy grew even stronger in the 20th century as interest in the American West surged. Scholars and critics rediscovered his impact on both art and conservation. Exhibitions and retrospectives honored his contributions.

Today, Moran is recognized not only as a great painter but as a foundational figure in American visual culture. His commitment to depicting nature’s grandeur helped shape national identity. Through his brush, he communicated values of wonder, respect, and stewardship. Those values still resonate with viewers nearly a century after his death.

Moran’s Place in American Art History

Thomas Moran occupies a unique place in American art history. He was not simply a landscape painter but a cultural figure who helped define how Americans see their land. His work played a critical role in connecting visual art with national pride and environmental awareness. He captured the scale, power, and mystery of a still-emerging country.

His paintings contributed to the burgeoning conservation movement of the late 19th century. Along with writers and scientists, Moran gave Americans a reason to care about preserving wild spaces. His art wasn’t political—it was patriotic, grounded in love of country and reverence for God’s creation. Moran helped people see nature as part of the national character.

More Than a Landscape Painter

Moran worked closely with government agencies, producing art that was used in promotional and scientific materials. His collaborations with surveyors, explorers, and politicians made him a trusted figure in national projects. This fusion of public service and personal vision made his role unique. He was both a documentarian and a dreamer.

Today, his work continues to be studied, displayed, and admired. His influence extends beyond art galleries into textbooks, documentaries, and national park signage. His vision of America—vast, wild, and awe-inspiring—remains deeply embedded in the national psyche. Thomas Moran gave America a face, and that face was carved in canyon walls and mountain peaks.

Key Takeaways

- Thomas Moran was born in England in 1837 and emigrated to the U.S. in 1844.

- His 1872 painting of Yellowstone helped establish the first national park.

- Moran married fellow artist Mary Nimmo Moran in 1863.

- He became known as “the American Turner” for his dramatic landscapes.

- His work remains a foundation of American landscape painting and heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions

- When was Thomas Moran born?

February 12, 1837, in Bolton, England. - What was Moran’s most famous painting?

“The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone,” completed in 1872. - How did Moran influence American conservation?

His paintings helped convince Congress to protect Yellowstone. - Who did Thomas Moran marry?

He married artist Mary Nimmo Moran in 1863. - Where can his work be seen today?

His paintings are held in the Smithsonian, National Gallery, and others.