Marie Bracquemond, born on December 1, 1840, in Argenton-en-Landunvez, Brittany, France, was a talented French Impressionist painter whose artistic contributions were significant but often overshadowed by the prevailing gender norms of the 19th century. Bracquemond navigated the challenges of being a female artist in a male-dominated art world, and her works, marked by a unique blend of Impressionist and traditional techniques, have gained recognition for their beauty and innovation.

Marie Quivoron, as she was known before her marriage, demonstrated an early aptitude for art. She began her formal training at the age of 16 under the tutelage of landscape painter M. Aubry-Lecomte. Her passion for painting led her to further studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a groundbreaking choice for a woman in the mid-19th century. At the school, she encountered fellow artists who would later become key figures in the Impressionist movement.

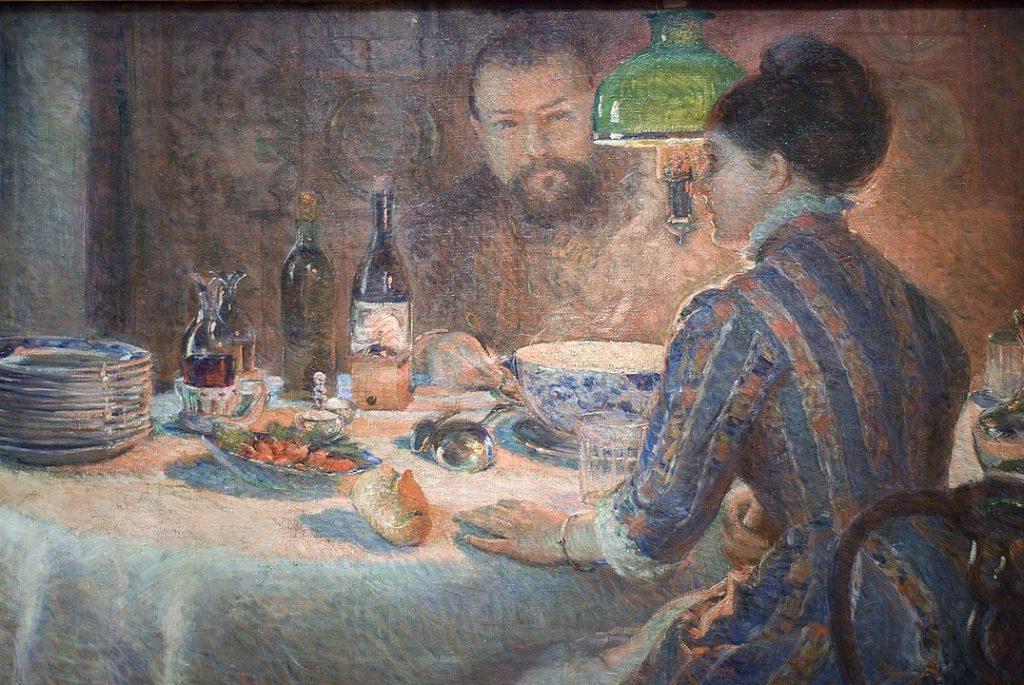

In 1869, Marie married Félix Bracquemond, a successful engraver and painter. Félix was acquainted with prominent artists of the time, including Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, and his connections provided Marie with entry into the Parisian art scene. The couple’s home became a meeting place for artists and intellectuals, exposing Marie to the revolutionary ideas and techniques emerging in the art world.

Despite her connections and artistic aspirations, Marie faced the challenges imposed by societal expectations of women during the 19th century. The prevailing notion was that a woman’s primary role was as a homemaker, and pursuing a professional career was often frowned upon. However, Marie’s determination and talent allowed her to navigate these constraints.

In the early 1870s, Bracquemond began exhibiting her works at the Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Her paintings, which often depicted scenes of everyday life, received positive attention, establishing her as a notable artist. However, the rigid and conservative nature of the Salon limited artistic innovation, and Bracquemond, along with other like-minded artists, sought alternatives.

The turning point in Bracquemond’s career came with her introduction to the Impressionist circle. She became close friends with Berthe Morisot and exhibited with the Impressionists in 1874, participating in the groundbreaking independent exhibition that marked the birth of the Impressionist movement. This move aligned her with artists like Monet, Degas, and Pissarro, who were challenging traditional artistic conventions.

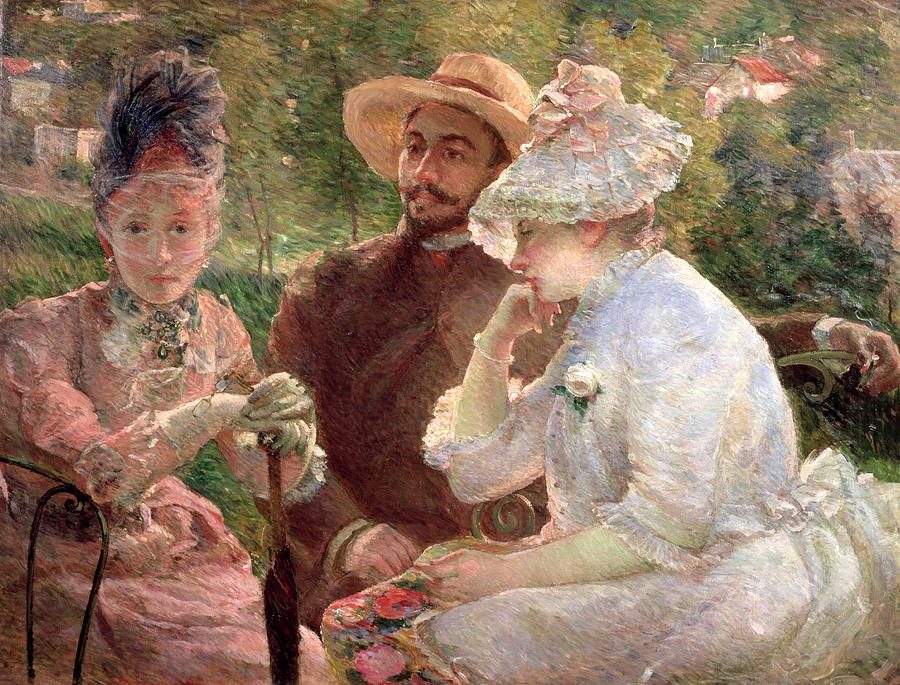

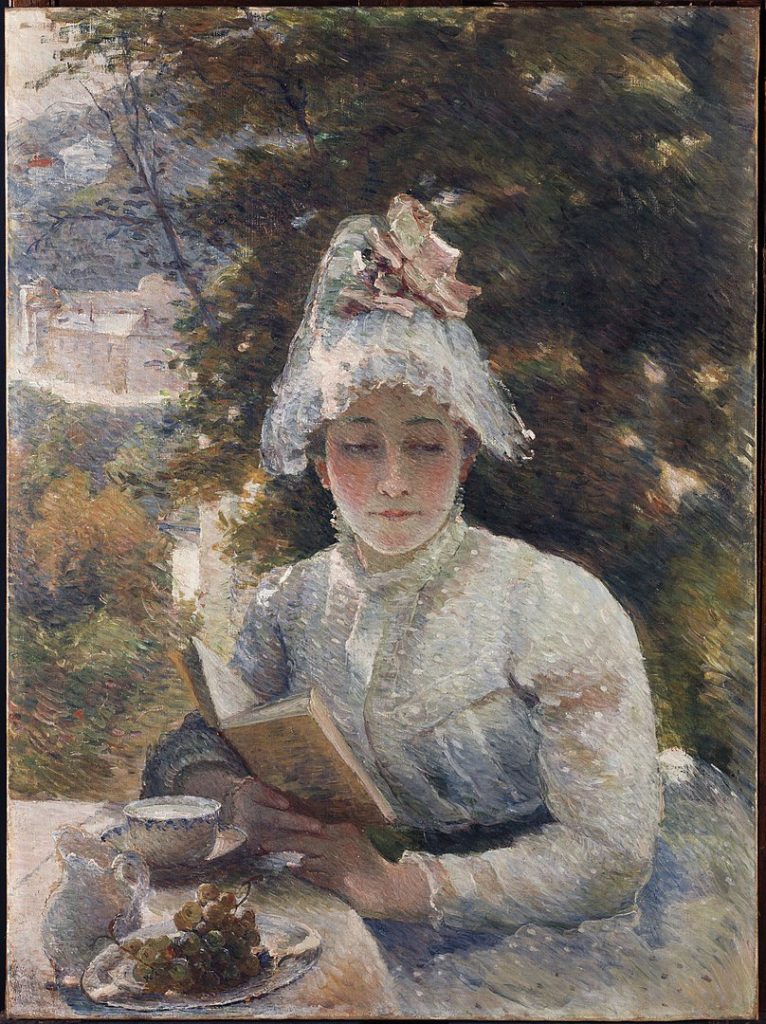

Bracquemond’s association with the Impressionists influenced her artistic style. The movement, characterized by its emphasis on capturing the fleeting effects of light and color, resonated with her. She adopted a looser brushstroke and a brighter palette, moving away from the more traditional academic approach. Her painting “On the Terrace at Sèvres” (1880) is a notable example of her Impressionist-influenced style, portraying a leisurely scene with vibrant colors and dappled sunlight.

While Bracquemond embraced Impressionist techniques, she retained elements of her academic training, creating a unique fusion that set her apart. Her ability to blend traditional and innovative approaches resulted in paintings that captured the spirit of the time while maintaining a sense of individuality. This balance is evident in works like “Self-Portrait with Three Fingers” (c. 1885), a striking and introspective piece that showcases her technical skill and introspective gaze.

Despite her involvement with the Impressionist movement, Bracquemond faced challenges unique to her gender. The art world of the time was reluctant to fully embrace female artists, and her contributions were sometimes overshadowed by the male figures dominating the narrative. Bracquemond herself struggled with the conflicts between her roles as an artist, wife, and mother.

Her marriage to Félix Bracquemond brought both support and challenges. Félix was supportive of Marie’s artistic endeavors, but societal expectations weighed heavily on her. The birth of their son, Pierre, added further responsibilities, and Bracquemond’s ability to balance her roles became a source of internal conflict. She stepped back from the public art scene and focused more on family life during the 1880s.

In 1886, Bracquemond participated in the final Impressionist exhibition. Her relationship with the movement had become strained due to personal and artistic differences, and she chose to distance herself from the group. She continued to exhibit at the Salon and other venues but remained somewhat detached from the evolving art scene.

The latter part of Bracquemond’s life saw a shift in her artistic focus. She turned to ceramics, exploring the decorative arts. Collaborating with the prestigious Sèvres porcelain factory, she produced a series of exquisite designs. Her venture into applied arts showcased her versatility and skill in different mediums.

Marie Bracquemond’s legacy extends beyond her paintings. Her contributions to the Impressionist movement, though sometimes overlooked, are increasingly recognized. Her ability to navigate the challenges imposed by societal norms and to maintain her artistic identity is commendable. The delicate balance she achieved between traditional and innovative approaches to art remains a testament to her enduring influence.

Marie Bracquemond passed away on January 17, 1916, in Paris. While her artistic career faced complexities due to societal constraints, her legacy has gained renewed appreciation in contemporary art discourse. The recognition of her role as a pioneering female artist within the Impressionist movement underscores the significance of her contributions to the rich tapestry of art history.