Hector Guimard, born on March 10, 1867, in Lyon, France, was an architect and designer who became one of the most prominent representatives of the Art Nouveau movement in France. His work is celebrated for its organic forms, flowing lines, and integration of architecture with decorative arts, making him a pivotal figure in the transition towards modern architecture and design in the early 20th century. Guimard’s legacy is most visibly preserved in the iconic entrances of the Paris Métro, which epitomize the Art Nouveau ethos by blending functionality with aesthetic elegance.

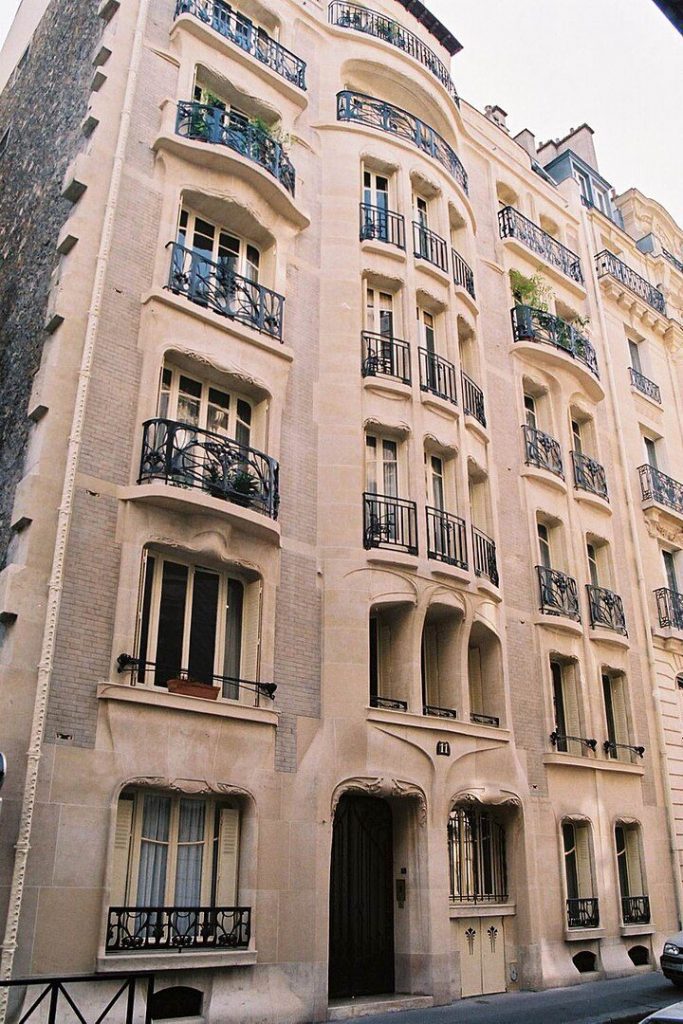

Educated at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Guimard was initially influenced by neoclassicism before embracing the Art Nouveau style, which sought to harmonize architectural structures with their natural surroundings through the use of organic shapes and motifs. His breakthrough came with the design of the Castel Béranger (1895-1898), a residential building in Paris that garnered public acclaim and marked Guimard’s emergence as a leader in the new architectural movement.

Total Work of Art

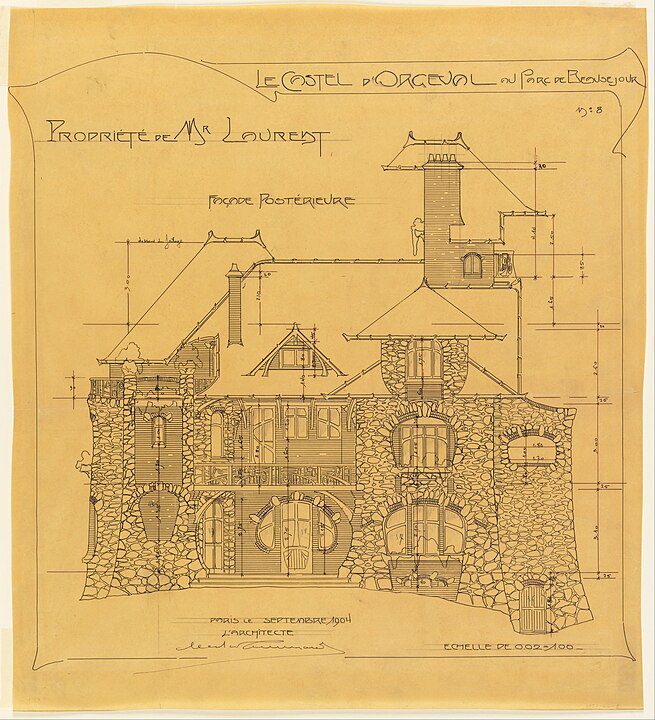

Guimard’s philosophy extended beyond mere architectural form; he advocated for a Gesamtkunstwerk or “total work of art,” wherein every element of a building, from the structure to the interior decorations and furnishings, was designed as an integral part of the whole. This approach led him to design not only buildings but also furniture, fixtures, and even graphic elements such as typography, thus creating a cohesive visual and functional experience.

The Paris Métro entrances designed by Guimard for the 1900 Exposition Universelle are perhaps his most enduring contribution to public art and architecture. These entrances, characterized by their whimsical, organic forms and use of cast iron and glass, were intended to harmonize with the city’s streetscape while inviting passengers into the modern underground world of urban transit. Though some were dismantled in the mid-20th century, many have been preserved or reconstructed, serving as enduring symbols of Paris and the Art Nouveau movement.

Despite his success, Guimard’s career faced challenges in the changing tastes of the early 20th century, as the Art Nouveau style gave way to Art Deco and Modernism. His later works, such as the Guimard Synagogue (1913), reflected a simplification of form and a move towards functionalism, albeit without abandoning his signature organic aesthetic.

Guimard’s personal life, particularly his marriage to American painter Adeline Oppenheim, played a significant role in his career, influencing his connections and opportunities, including his work in the United States. However, with the advent of World War II and the rise of anti-Semitic sentiment, Guimard, whose wife was Jewish, faced increasing persecution. The couple eventually fled to New York, where Guimard lived until his death on May 20, 1942.

Overshadowed No More

In the decades following his death, Guimard’s contributions to architecture and design were somewhat overlooked, overshadowed by the dominance of Modernism. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a resurgence of interest in his work, with a greater appreciation for his role in shaping the visual landscape of Paris and his influence on the development of modern design principles.

Today, Hector Guimard is celebrated as a visionary who infused the urban fabric with a sense of dynamism and organic beauty, forever changing the way we think about architectural space and its relationship to natural forms. His work stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of Art Nouveau and its capacity to enchant, innovate, and inspire.