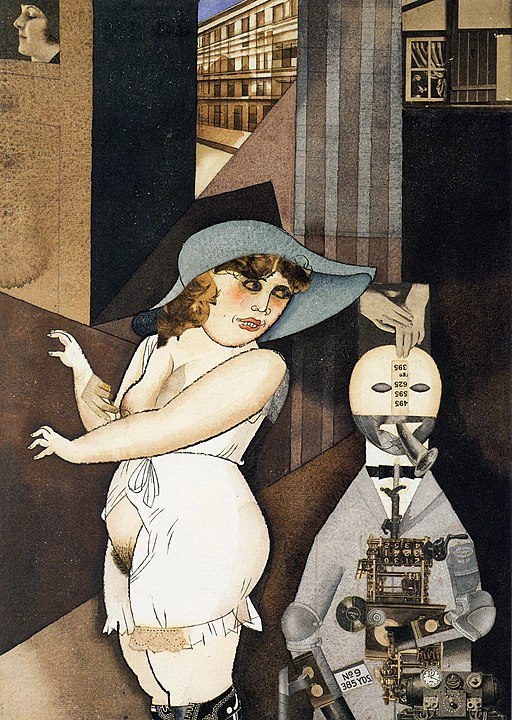

George Grosz, born Georg Ehrenfried Groß on July 26, 1893, in Berlin, Germany, was a pivotal figure in the Dada and New Objectivity movements, renowned for his caustic portrayals of Weimar society, corruption, and the horrors of war. His work, characterized by sharp social critique delivered through biting satire and grotesque caricatures, cemented his legacy as one of the most influential artists of the early 20th century. Grosz’s art was a mirror to the tumultuous times he lived through, reflecting the artist’s deep disillusionment with society and his fervent desire for political change.

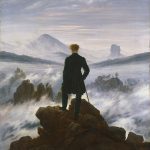

The early years of Grosz’s life were marked by hardship and a burgeoning talent for drawing. His father’s death when Grosz was young and the family’s subsequent financial difficulties did not deter him from pursuing his passion for art. He attended the Dresden Academy of Art and later the Berlin College of Arts and Crafts, where he was exposed to the works of the Old Masters, which would influence his technical skills. However, Grosz’s artistic direction took a radical turn with his exposure to contemporary movements like Expressionism and his involvement with the Dadaists, whose anti-art sensibilities resonated with his growing discontent with society and the art establishment.

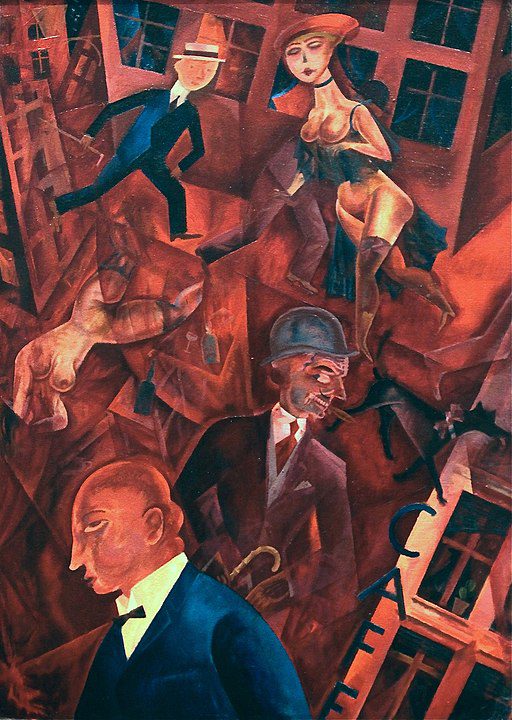

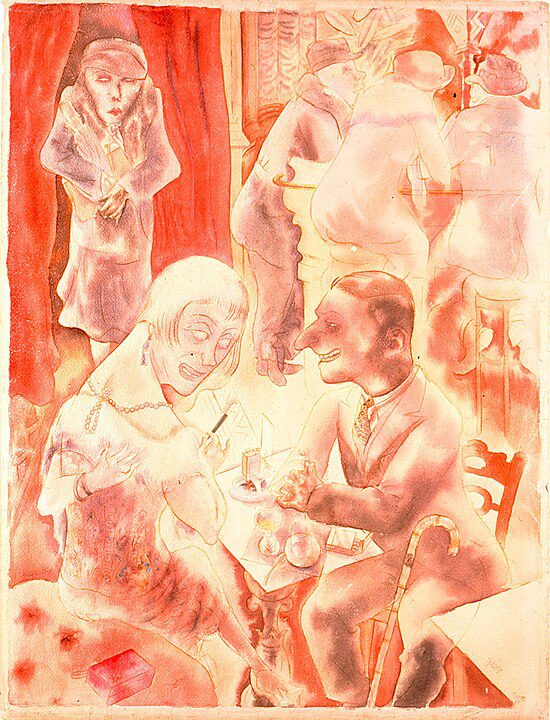

Grosz’s experiences during World War I, where he served briefly before being discharged due to health issues, deeply affected him and became a central theme in his work. His drawings and paintings from this period are filled with images of mutilated soldiers, corrupt officials, and the dehumanizing effects of modern urban life, serving as a powerful indictment of the war and the societal structures that supported it. Works such as “Fit for Active Service” (1918) and “The Pillars of Society” (1926) showcase Grosz’s skill in using art as a weapon against the hypocrisy and moral bankruptcy he saw in German society.

Social Realities

In the 1920s, Grosz became associated with the New Objectivity movement, which sought to depict the social realities of the Weimar Republic with blunt realism and sharp social commentary. His work from this period is characterized by its detailed, realistic style and its focus on the themes of urban life, political corruption, and social alienation. Grosz’s art was not merely observational; it was a direct challenge to the viewer, demanding engagement and eliciting discomfort with its stark portrayal of societal ills.

Grosz’s outspoken political views and his condemnation of the National Socialist Party made him a target for persecution. In 1933, shortly after Hitler’s rise to power, Grosz emigrated to the United States, where he continued his career as an artist and teacher. While his work in the United States shifted towards a less overtly political focus, exploring more abstract and existential themes, it retained its critical edge and satirical sharpness.

Displacement & Nostalgia

Despite achieving success and recognition in his adopted country, including becoming a naturalized citizen in 1938, Grosz grappled with feelings of displacement and nostalgia for his homeland. This period of his life was marked by a continued exploration of new artistic styles and techniques, but he often expressed dissatisfaction with the commercialization of art in America and the loss of the urgent, political purpose that had defined his earlier work.

Grosz returned to Berlin in 1959, where he died on July 6, 1959, shortly after his arrival. His legacy, however, endures in the power of his art to provoke, critique, and unsettle. George Grosz’s body of work remains a searing commentary on the failings of society, the folly of war, and the enduring human capacity for cruelty and indifference. Through his incisive illustrations, paintings, and writings, Grosz left an indelible mark on the art world, standing as a testament to the role of the artist as a social critic and a relentless seeker of truth.