Frederick Law Olmsted, a visionary landscape architect and urban planner, was born on April 26, 1822, in Hartford, Connecticut. Raised in a prosperous family, Olmsted’s early life was marked by a variety of experiences, from sailing to farming, which contributed to his keen observational skills and understanding of the natural world. Despite facing financial setbacks and the untimely death of his father, Olmsted’s upbringing fostered a deep appreciation for nature and an inclination towards social reform.

In 1850, Olmsted embarked on a transformative journey through the Southern United States. Commissioned by the New York Daily Times to report on the region’s slave-based agricultural economy, Olmsted’s observations became the foundation for his influential work, “A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States.” His writings highlighted the stark contrast between the Southern plantation system and the pastoral landscapes of the English countryside, foreshadowing his future endeavors in landscape design.

The pivotal moment in Olmsted’s career came in 1857 when he, along with architect Calvert Vaux, won the design competition for New York City’s Central Park. This marked the beginning of a prolific partnership between the two, leading to the establishment of the first full-fledged landscape architecture firm in the United States. The duo’s design for Central Park, with its meandering paths, scenic vistas, and carefully curated natural elements, set a new standard for urban parks and cemented Olmsted’s reputation as a pioneering landscape architect.

Beyond parks

Olmsted’s vision extended beyond individual parks; he sought to create comprehensive park systems that would enhance the quality of urban life. His influential writings, such as “Public Parks and the Enlargement of Towns” (1870), advocated for the social and environmental benefits of parks in rapidly industrializing cities. His ideas emphasized the importance of green spaces in promoting physical and mental well-being, fostering a sense of community, and mitigating the social and environmental challenges of urbanization.

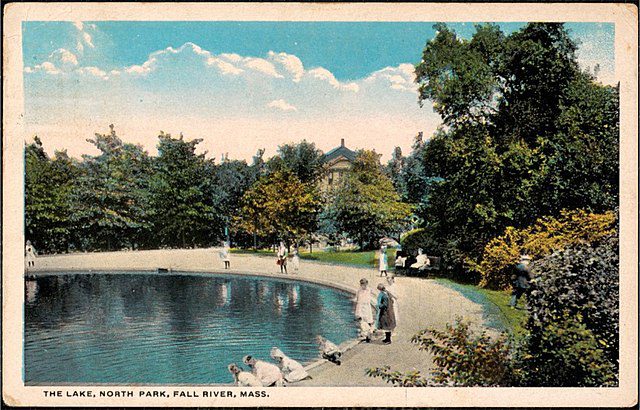

The success of Central Park paved the way for Olmsted to contribute to a myriad of projects that shaped the American landscape. From the design of Prospect Park in Brooklyn to the Emerald Necklace in Boston, Olmsted’s portfolio showcased his commitment to creating harmonious spaces that seamlessly integrated nature into the urban fabric. The Emerald Necklace, a chain of interconnected parks and parkways, exemplified Olmsted’s holistic approach, providing a continuous green corridor that offered respite from the urban hustle.

Olmsted’s influence extended beyond the realm of parks. He played a pivotal role in the planning and design of university campuses, including Stanford University and the University of Chicago. His vision for these institutions emphasized the importance of open spaces, careful site planning, and an environment conducive to intellectual and social engagement.

In the latter part of the 19th century, Olmsted expanded his focus to landscape conservation. Appointed as the head of the newly established Yosemite Commission in 1864, he played a key role in the protection of Yosemite Valley. His advocacy for the preservation of natural landscapes laid the groundwork for the establishment of the National Park system, a testament to his foresight in recognizing the intrinsic value of America’s natural treasures.

Harmonizing with surroundings

Olmsted’s commitment to social reform was evident in his work on projects such as the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. Commissioned by George Washington Vanderbilt II, Olmsted designed the estate’s grounds to harmonize with the surrounding natural environment while addressing practical considerations such as forestry and sustainable land management. This approach reflected Olmsted’s belief that thoughtful design could enhance both the aesthetic and functional aspects of a landscape.

The latter part of Olmsted’s career saw his involvement in urban planning projects. He contributed to the development of the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893, where his “White City” design showcased neoclassical architecture set within a carefully landscaped environment. His efforts in Chicago reinforced his belief in the transformative power of well-designed public spaces to uplift and inspire communities.

Olmsted’s legacy extended to his family, as his sons, John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., continued his work after his retirement. The Olmsted Brothers firm played a significant role in shaping American landscapes throughout the early 20th century, further solidifying the family’s imprint on the field of landscape architecture.

Despite facing personal challenges, including battles with mental health issues and financial setbacks, Frederick Law Olmsted’s contributions to American landscape architecture were immense. His legacy is etched into the fabric of countless parks, campuses, and urban spaces that continue to enrich the lives of generations. Frederick Law Olmsted passed away on August 28, 1903, leaving behind a legacy that transcends his time, a testament to the enduring impact of his vision for harmonious and functional landscapes that resonate with the human spirit.