Frederic Edwin Church holds a distinguished place in the history of American art as one of the most important figures in 19th-century landscape painting. Best known for his grand, panoramic depictions of nature, he captured the awe-inspiring beauty of the American wilderness during a time when the young nation was defining its identity. As a leading member of the Hudson River School, Church helped establish a distinctly American approach to painting that blended realism with idealism. His works are marked by their intricate detail, dramatic lighting, and a reverent portrayal of the natural world.

Born on May 4, 1826, in Hartford, Connecticut, Church would go on to become one of the most celebrated painters of his time. His career spanned five decades, during which he traveled the world in search of sublime landscapes to paint. Through his art, he communicated themes of exploration, faith, and national pride. Even long after his death on April 7, 1900, his legacy endures in major American art institutions.

Church’s paintings were not merely decorative; they carried deep meaning and national significance. At a time when America was expanding westward and defining its cultural identity, his works offered a powerful vision of the land’s beauty and potential. He painted places Americans had never seen but longed to imagine—towering mountains, mighty rivers, and glowing tropical valleys.

Today, Church is recognized as one of the finest landscape painters of the 19th century. His contributions to American art have been revived and re-examined by scholars and art lovers alike. From Niagara to The Heart of the Andes, his paintings continue to captivate with their scale and emotion. In every brushstroke, Church offered not just a view of the world, but a vision of the divine in nature.

Early Life and Education

Frederic Edwin Church was born into a prosperous family on May 4, 1826, in Hartford, Connecticut. His father, Joseph Church, was a successful businessman and financier, which allowed young Frederic the freedom to pursue his interests without the financial constraints many artists faced. From a young age, Church showed exceptional talent in drawing and painting, often sketching from nature in the fields and woods near his home. His early exposure to the New England landscape would later inform the spiritual and majestic elements of his mature works.

At just 18 years old in 1844, Church began formal training under Thomas Cole, widely regarded as the founder of the Hudson River School of painting. Cole’s studio in Catskill, New York, offered a rigorous environment focused on classical composition and romantic naturalism. Church became his only pupil to live and study with him full-time, and the experience deeply shaped his artistic direction. Under Cole’s guidance, Church learned how to express moral and philosophical ideas through landscape, a theme that would remain central to his work.

Hartford Roots and Early Talent

Church’s education did not follow the traditional academic path of European study, as many American artists did at the time. Instead, he focused intensely on the American landscape, believing it was worthy of the same reverence given to the Alps or the Mediterranean. He also began studying scientific principles related to geology and botany, which contributed to the accuracy of his depictions of nature. This combination of scientific curiosity and artistic skill gave his paintings a unique and authentic quality.

By the late 1840s, Church was already exhibiting his work and receiving praise for his compositions. His first major public showing came in 1847 at the National Academy of Design in New York City, a respected institution that would later elect him as a full academician. These early successes confirmed that he was on the right path and positioned him for a long, influential career. With a solid foundation in both art and nature, Church was ready to expand his vision far beyond the Hudson Valley.

Mentorship and Artistic Formation

The mentorship of Thomas Cole played a vital role in shaping Frederic Edwin Church’s artistic voice. Cole’s approach emphasized the spiritual power of nature and the moral messages landscapes could convey. Church absorbed these teachings but developed his own style that was more grounded in empirical observation and scientific detail. While Cole painted allegorical scenes with symbolic meanings, Church aimed for visual accuracy and emotional intensity. Together, they represent two sides of the Hudson River School’s ideals.

After two years under Cole’s tutelage, Church struck out on his own in 1846. His early independent works still bore the imprint of his teacher but showed growing technical prowess and originality. That same year, he completed Hooker and Company Journeying through the Wilderness, an ambitious painting that combined historical subject matter with majestic scenery. The work was praised for its storytelling and use of light, signaling Church’s readiness to emerge as a major figure in American painting.

Thomas Cole and the Hudson River School Legacy

In 1848, Church was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design and, by 1849, became the youngest full member at just 23 years old. This recognition placed him in the center of the New York art world and connected him with wealthy patrons, galleries, and critics. He began to distinguish himself from his peers by painting not only American scenes but also far-flung landscapes from his global travels. These early years laid the groundwork for the signature works that would follow in the 1850s and 1860s.

During this period, Church refined his technique to include increasingly intricate details and subtle gradations of light. His works featured dramatic contrasts between shadow and sunlight, rolling clouds, and vast skies. Yet, they never lost sight of compositional harmony. His growing commitment to accuracy and realism was balanced with poetic grandeur, a blend that captivated the American public. As the 1850s dawned, Church was poised to become the country’s most celebrated landscape artist.

Rise to Fame: Signature Works and Style

The year 1857 marked a turning point in Church’s career with the debut of Niagara, a monumental painting of the famous waterfall that stunned viewers with its realism and scale. Measuring over seven feet wide, it captured the raw power and endless motion of the falls with photographic precision. Exhibited in New York and later in London, Niagara attracted thousands and solidified Church’s status as a painter of international stature. Critics hailed it as a masterpiece, and the public was awed by its lifelike energy.

In 1859, Church unveiled The Heart of the Andes, a painting more than five feet tall and ten feet wide, inspired by his travels in South America. Displayed in a darkened room and lit like a stage set, the painting was treated almost like a religious relic. Viewers paid admission to stand before it, often moved to tears by its beauty. It was a cultural phenomenon and helped redefine how Americans experienced art. Church’s genius lay in blending theatrical presentation with meticulous attention to topographical detail.

Masterpieces That Captivated a Nation

Church’s style during this peak period can be described as panoramic realism infused with spiritual reverence. He used vivid, almost glowing colors and complex compositions to evoke awe. Works like The Icebergs (1861) and Cotopaxi (1862) expanded his subject matter to include arctic and volcanic landscapes. These paintings conveyed both the majesty and danger of nature, often interpreted as metaphors for political and spiritual turmoil during the Civil War era. Church’s art spoke to the cultural moment while remaining deeply rooted in natural observation.

A key element of his success was his marketing savvy. Church managed his exhibitions like theatrical events, using lighting, curtains, and descriptive pamphlets to guide the viewer’s experience. This approach transformed art from a passive encounter into an emotional journey. He sold engravings of his paintings to reach a broader audience, helping to democratize art consumption in America. By the early 1860s, Church was not just a painter—he was a national icon of American artistic achievement.

Travels and Influence Abroad

Frederic Edwin Church’s passion for geography and natural science led him far beyond the American landscape. In 1853, he traveled to South America, retracing the path of Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. Church explored Colombia and Ecuador, sketching volcanoes, jungles, and valleys along the Andes Mountains. These journeys provided him with firsthand studies of equatorial light and exotic flora, which he incorporated into his masterworks. His return trip in 1857 provided further inspiration for The Heart of the Andes.

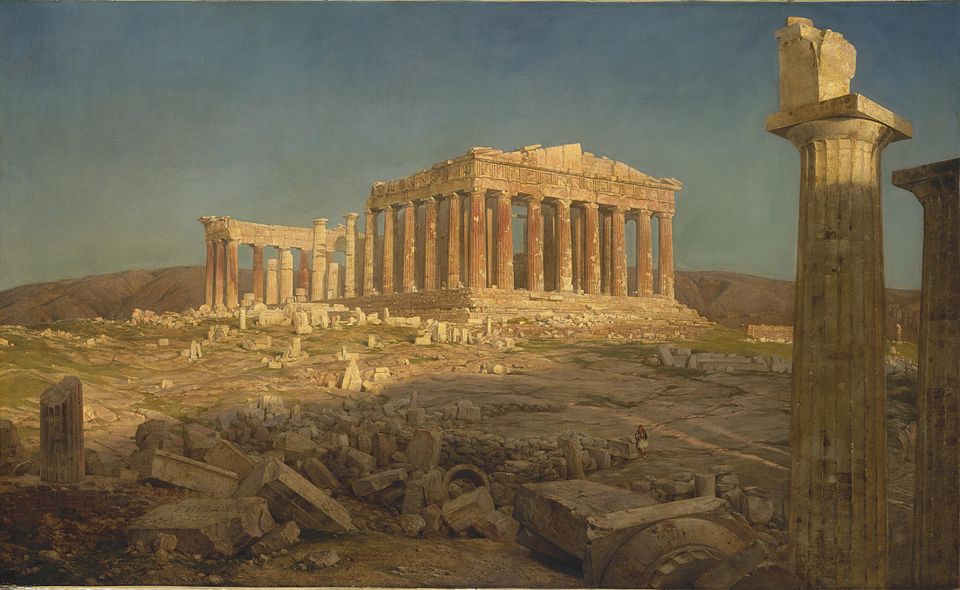

Church’s travels were not just adventurous; they were deliberate acts of artistic research. He carried sketchbooks, scientific instruments, and guidebooks, carefully documenting everything from weather patterns to plant species. His 1867 trip to the Middle East included visits to Jerusalem, Petra, and Baalbek. These expeditions fueled a shift in his later works toward spiritual and historical themes, particularly focusing on biblical landscapes and ancient ruins. His paintings from this era combine exoticism with a reverence for sacred geography.

Painting the World – Church’s Global Voyages

Among his most memorable foreign-inspired works is El Khasné, Petra (1874), based on a site visit to the famed Jordanian ruins. The painting captures the rose-colored rock face bathed in shadow and light, evoking both archaeological curiosity and spiritual reflection. Through such images, Church invited viewers to contemplate the divine hand behind even the most distant corners of the Earth. His engagement with global scenery expanded the American artistic vocabulary beyond national borders.

Church’s global pursuits reinforced his belief that nature was a manifestation of divine order. He painted not for sensationalism but to elevate the viewer’s understanding of God’s creation. These works also aligned with 19th-century American Protestant values, which saw exploration and science as compatible with faith. His landscapes became visual sermons—grand, illuminating, and morally uplifting. In this way, Church’s international travels not only expanded his visual repertoire but deepened his spiritual and national vision.

Personal Life and Legacy

In June 1860, Frederic Church married Isabel Carnes, beginning a new chapter marked by both joy and sorrow. They had four children together, though tragedy struck in 1865 when their two youngest died of diphtheria within a week of each other. This loss profoundly affected Church and led to a period of reduced artistic output. Despite personal grief, he continued to create, often focusing on themes of renewal, light, and spiritual endurance in his later works.

As a retreat and creative refuge, Church began building his home, Olana, in the mid-1860s. Located near Hudson, New York, the Persian-style mansion reflected his love for exotic architecture and panoramic views. He designed it in collaboration with architect Calvert Vaux, co-designer of Central Park. Completed in 1872, Olana was a culmination of Church’s artistic ideals—a place where art, architecture, and nature converged. Its interiors were filled with Church’s paintings, artifacts from his travels, and custom furnishings.

Family, Tragedy, and Olana

Olana’s design included a series of planned vistas and carriage roads, each offering framed views of the surrounding Hudson Valley. The estate was intended not just as a residence but as a “total work of art,” where the landscape itself became a canvas. Visitors were—and still are—struck by the harmony between the home and its environment. Today, Olana is preserved as a National Historic Landmark and serves as a museum celebrating Church’s legacy.

Church’s commitment to preserving and glorifying nature left a profound legacy on American landscape art. He inspired generations of artists to explore realism, light, and national identity through their work. Though his popularity waned with the rise of modernism, his contributions were later reappraised as foundational to American cultural history. Through both his canvases and Olana, Frederic Edwin Church left a legacy of enduring beauty and national pride.

Final Years and Enduring Impact

As Frederic Church aged, he began to suffer from rheumatoid arthritis, a painful condition that limited the use of his right hand. Despite this, he continued to paint into the 1890s, though at a slower pace and often on a smaller scale. He spent most of his later years at Olana, overseeing its grounds, hosting guests, and occasionally painting when his health allowed. These years were quieter but still filled with reflection and artistic vision.

Church passed away on April 7, 1900, at the age of 73, at his beloved home in Olana. At the time of his death, artistic tastes in America had shifted toward Impressionism and modernist abstraction, leaving Church and the Hudson River School out of fashion. His achievements were largely forgotten for much of the early 20th century. However, his work continued to be preserved in museum collections, awaiting rediscovery.

Death and Rediscovery of a Master

In the 1960s and 70s, a wave of scholarly interest brought Church back into public and academic attention. Exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other major institutions reintroduced audiences to his extraordinary skill and vision. Historians began to see Church not just as a painter of pretty scenes, but as a national storyteller and spiritual chronicler. His reputation steadily rose, and today he is celebrated as one of America’s greatest landscape artists.

Frederic Edwin Church’s work remains on display in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Wadsworth Atheneum, and many others. His influence continues through the revival of realism and the appreciation of landscape art that communicates both beauty and meaning. More than a century after his death, Church’s vision still resonates—reminding us of the power of nature, faith, and artistic mastery.

Key Takeaways

- Frederic Edwin Church was born on May 4, 1826, in Hartford, Connecticut.

- He trained under Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson River School.

- His major works include Niagara, Heart of the Andes, and Cotopaxi.

- Church built Olana, a Persian-style estate overlooking the Hudson River.

- He died on April 7, 1900, and is now recognized as a key figure in American art.

FAQs

- What style of painting is Frederic Church known for?

He is best known for panoramic landscapes in the Hudson River School style. - Where did Frederic Church travel for inspiration?

He traveled to South America, Europe, the Middle East, and the Arctic. - What is Olana?

Olana is Church’s home and estate, now a historic site and museum in New York. - Did Frederic Church have children?

Yes, he had four children, but two died in infancy from diphtheria. - Why did Church fall out of favor after his death?

Changing art trends moved toward modernism, temporarily eclipsing his work.