The first art of Alaska was not made to hang on walls or be admired in galleries, but to carry memory, mark the sacred, and bind people to an environment that demanded resilience and imagination in equal measure. Across the vast expanse of the region—ice-swept coastlines, boreal forests, and mountainous interiors—art emerged not as a separate pursuit but as an inseparable element of survival, ritual, and identity.

Carvings in Stone, Bone, and Ivory

Archaeological sites scattered from the Aleutian Islands to the Arctic Slope reveal a continuity of creative expression stretching back thousands of years. Small carvings made from walrus ivory, whalebone, and caribou antler served as tools, amulets, and vessels of spiritual power. Many depict sea mammals—seals, whales, walruses—rendered with remarkable economy of line. These were not mere naturalistic studies; they were acknowledgments of a relationship between hunter and hunted, human and animal spirit. A harpoon head carved with minute detail was simultaneously a functional object and a symbolic invocation of success.

Stone figures, often abstracted, have been found buried in village sites dating back more than two millennia. Some have hollow eyes where inlays of jet or ivory once glimmered, suggesting that even in deep antiquity Alaskan artists understood the expressive power of contrast and material interplay. These early works demonstrate how utility and art fused: a lamp carved from soapstone held fire, but its form might also include etched designs linking it to kinship or myth.

Three qualities stand out in these earliest objects:

- A reliance on local materials transformed with remarkable skill.

- The embedding of spiritual meaning within daily tools.

- A visual shorthand that balanced abstraction with representation.

Such traits would echo through centuries of Alaskan art, resurfacing in masks, textiles, and modern sculpture alike.

Petroglyphs and the Language of Marks

Along coastal rocks in southeastern Alaska, petroglyphs cut into stone reveal another layer of visual culture. Spirals, faces, and stylized animals were carved into bedrock at the waterline, where tides rise and fall, suggesting an intentional dialogue with natural rhythms. Some scholars propose they served as territorial markers or warnings; others interpret them as spiritual inscriptions linked to salmon runs or mythic narratives. The ambiguity itself testifies to their layered purpose: both public sign and private code.

Unlike the monumental totem poles that would later dominate the coastal landscape, these petroglyphs are subtle, requiring a certain light or angle to reveal their forms. That elusiveness may have been part of their meaning. A traveler passing at dawn might see a whale etched into stone, while at high noon it disappeared back into the surface. The land itself became a shifting canvas, refusing permanence.

An evocative anecdote survives from 19th-century travelers who described Native guides pausing before petroglyph sites, touching the carved spirals, and offering small tokens of respect. Even after centuries, the stones remained active participants in cultural memory, not abandoned relics. This interplay between permanence and ephemerality would remain central to Alaskan art, reflecting the delicate balance of life in a place where glaciers carve valleys and seasons erase traces overnight.

Cosmology in Form and Symbol

Beyond the visible record, Alaskan art carried the weight of cosmological explanation. Oral traditions describe a universe in which humans and animals crossed boundaries freely; a seal might shed its skin to become a woman, or a raven might fashion the sun from a box. These stories did not remain in words alone but took tangible form. Amulets depicting transformation—half animal, half human—are among the most haunting artifacts of early Alaska. Their compact size belies their expansive meaning: they encoded a worldview in which existence was fluid, constantly shifting between states.

This cosmological dimension also shaped artistic decisions about scale and detail. A carved ivory figure might appear simple, yet a slight turn of the mouth or elongated limb carried symbolic weight. Artists were less concerned with verisimilitude than with evoking the liminal state between the seen and unseen. In this sense, early Alaskan art anticipates modernist strategies of abstraction, not by accident but by necessity: the invisible demanded a visual language beyond literal depiction.

What surprises many outside observers is the degree of continuity. A mask carved in the 19th century echoes the same transformational motifs as an ivory amulet from a site dated a thousand years earlier. Even as tools, dwellings, and migrations shifted, the artistic impulse to record the porous boundary between human and spirit endured.

The art of Alaska before contact was thus not peripheral decoration but a core means of sustaining a relationship with land, sea, and cosmos. Its makers did not distinguish between aesthetics and survival, between a useful harpoon and a sacred image. Both carried beauty, both carried meaning. And though centuries of colonial encounter would reshape materials and motifs, the deep grammar of Alaskan art—its intimacy with environment, its fusion of function and spirit, its refusal of strict boundaries—remains visible in every subsequent chapter.

Masks, Spirits, and Performance

To enter a world of Alaskan masks is to step into a theater where wood, pigment, and feathers are not inert materials but agents of transformation. Among the Yup’ik, Inupiat, and other northern peoples, masks were not simply carved objects; they were thresholds through which the human and the spirit worlds communicated. To see a mask in use was not to watch art but to participate in a vital ritual of exchange, where survival, gratitude, and imagination converged.

The Winter Festivals and Their Stage

Each winter, when the harsh Arctic dark pressed longest, villages gathered for ceremonies known as the Bladder Festival and other midwinter celebrations. These were occasions of renewal, honoring the spirits of animals that had sustained the community. Hunters believed that seals and other creatures willingly gave themselves to humans if treated with respect, and masks played a central role in this reciprocal bond.

In a semi-subterranean ceremonial house, the qasgiq, dancers wearing elaborately carved wooden masks enacted stories of hunts, dreams, and ancestral encounters. The flicker of seal-oil lamps animated painted faces, while feathers quivered with every beat of the drum. To outsiders, these gatherings might appear theatrical, but to participants they were necessary negotiations with unseen powers. The performance was prayer, entertainment, and history lesson all at once.

A Yup’ik elder once explained that a mask was “not what it looked like, but what it did.” That distinction captures the essence of this art: function over permanence, transformation over stasis. Masks were rarely kept; many were burned or left to decay after the ceremony, releasing their spiritual energy rather than preserving it as artifact.

The Imagery of Transformation

The most striking feature of Alaskan masks is their embrace of metamorphosis. A face may emerge from the jaws of a fish; a seal’s body might contain a human profile; concentric hoops often encircle central figures, symbolizing the flow of worlds or the echo of breath. These visual strategies dramatize the belief that all beings are interconnected and that boundaries between species, realms, and states of existence are fluid.

Certain masks were inspired by dreams. A carver might wake from a vision of a bird with human hands or a fish with antlers and translate that dream into wood and pigment. The mask thus materialized the subconscious, giving form to experiences that otherwise lived in memory alone. In this sense, Alaskan artists were early explorers of surrealism, long before the term existed, creating objects that externalized dream logic.

Unexpectedly, some masks reveal humor. Grinning visages, exaggerated noses, or deliberately lopsided forms suggest that playfulness was integral to ritual, reminding participants that laughter and joy were part of the sacred dialogue. In a land where survival was arduous, the ability to laugh with spirits was itself a form of resilience.

Masks Beyond the Ceremony

Though conceived for ritual, masks traveled beyond their villages through trade and, later, through the eyes of collectors. Russian traders in the 18th and 19th centuries marveled at the ingenuity of these creations, often acquiring them as curiosities without grasping their spiritual import. By the late 19th century, as missionary influence discouraged traditional ceremonies, many masks ceased to be made for ritual use and instead entered museums, where they were stripped of their performative context.

Yet the spirit of masking never disappeared. Contemporary Yup’ik and Inupiat artists have revived the tradition, carving masks not only for galleries but also for renewed community rituals. They confront the paradox of creating works once intended for ephemerality in a world that now prizes their preservation. Some carve deliberately fragile masks, echoing the old practice of burning them after use; others embrace the permanence of museum display as a new kind of storytelling.

What endures is the sense that masks are not passive objects but living presences. Even behind glass, they radiate an energy that hints at the drumbeat, the dance, the laughter, and the whispered prayers that once surrounded them. For Alaska, masks remain one of the most vivid expressions of how art and performance fused into a single act of survival and wonder.

Totem Poles and Clan Histories

The forests of southeastern Alaska rise with monumental cedar trees, and from their trunks generations of Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian carvers coaxed a distinct art form: the totem pole. Towering above villages and shorelines, these vertical sculptures served as heraldic markers, clan records, and narratives in wood. To call them “decorative” is to miss their function entirely; they were archives, theaters, and declarations of identity, carved into the very body of the forest.

The Cedar as Ancestral Medium

Red cedar was not chosen by chance. Its straight grain and resistance to decay made it an ideal material for monumental carving, and it held spiritual significance as a living partner in creation. Felling a cedar for a pole was accompanied by ritual acknowledgment of the tree’s spirit. Carvers did not begin with blank neutrality but with reverence for a being whose life would continue in another form.

Once prepared, the cedar became a surface where ancestral stories were stacked one atop another. The vertical structure of the pole mirrored social hierarchies and genealogical descent, placing crest figures in an order that conveyed both pride and obligation. The result was less a single narrative than a layered constellation of symbols: a raven here, a bear below, a human ancestor above. To read a pole required knowledge of clan histories, rivalries, and allegories. Outsiders often misinterpreted them as “idols,” but within their communities they functioned as sophisticated visual texts.

Three broad categories emerged:

- Heraldic poles, displaying clan crests and genealogical lineage.

- Mortuary poles, commemorating the dead and sometimes containing remains.

- Shame poles, erected publicly to call out debt or dishonor.

The diversity of these uses underscores the dynamism of the form—it was not fixed tradition but an evolving medium of communication.

Narrative Power and Political Weight

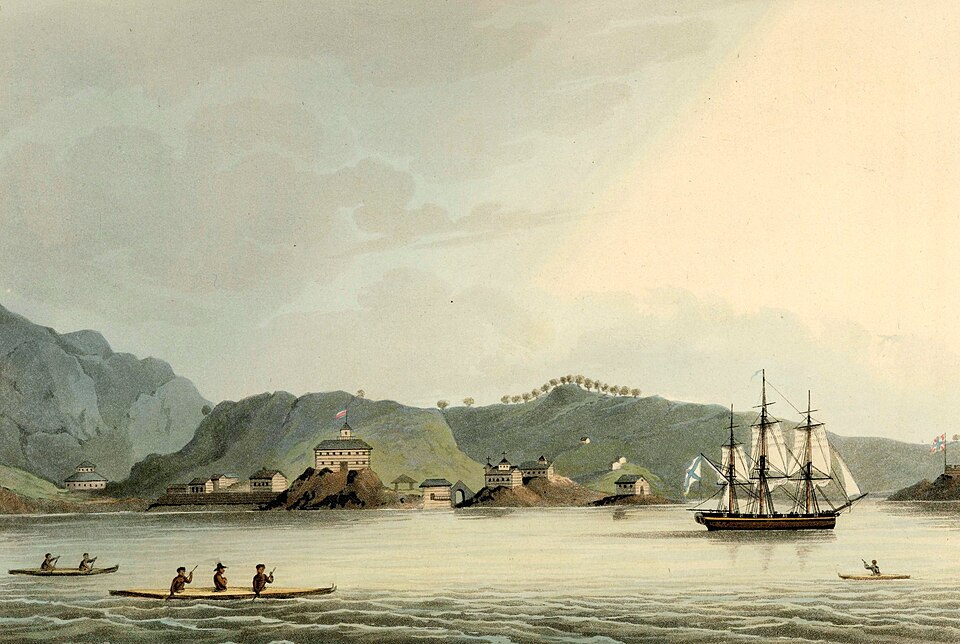

A totem pole was never neutral. Its imagery could assert dominance in disputes, declare alliances through marriage, or remind neighbors of an unpaid obligation. A prominent example often cited by oral historians is a pole erected in Sitka that displayed the figure of a Russian official, carved not in honor but in mockery, marking grievances between local clans and colonial authorities. Such poles demonstrate how the art form doubled as political theater, using scale and public visibility to enforce memory.

Equally important was the communal act of raising a pole. Entire villages participated, pulling ropes, singing songs, and feasting to celebrate its completion. The ceremony confirmed the pole’s significance as more than an object—it was a social event that bound participants together through collective effort and shared witnessing. The pole’s presence in the village thereafter carried the weight of that memory.

One unexpected dimension lies in the temporal rhythm of the poles. Cedar, though resilient, eventually decays. Unlike stone monuments, totem poles were not designed for eternity. Their slow return to the earth was accepted, even welcomed, as part of the cycle. The stories did not vanish with the wood; they persisted in oral tradition and could be re-carved anew. This impermanence aligned with a worldview in which history was continually renewed rather than frozen in a single form.

Survival, Suppression, and Renewal

The arrival of missionaries and American administrators in the 19th century brought sharp challenges. Carving poles was discouraged, sometimes outright banned, as authorities sought to suppress clan structures and spiritual traditions. Many poles were cut down or removed to distant museums. Villages emptied by epidemics left poles standing as ghostly sentinels, slowly leaning back into the forest.

Yet even during these periods of suppression, the memory of the poles endured. In the 20th century, revitalization efforts surged. Haida and Tlingit carvers trained younger generations, often collaborating with anthropologists or museum curators but insisting on cultural ownership of the practice. New poles were raised not only in Native communities but also in public spaces across Alaska, Canada, and beyond, asserting Indigenous presence and resilience.

Today, contemporary carvers such as Nathan Jackson and Robert Davidson have extended the tradition, blending ancestral forms with personal innovation. Some poles commemorate historical traumas; others celebrate renewal and continuity. In every case, the towering cedar columns remain visible evidence of how art in Alaska has never been a mere aesthetic pursuit but a social and political instrument of profound depth.

Totem poles embody the paradox of permanence and decay, memory and reinvention. They remind us that Alaska’s art history is not only recorded in museums but also written in wood that once breathed in the forest and now continues to breathe in public space.

Trade, Exchange, and Hybrid Styles

Art in Alaska has always been shaped by movement—of people, of goods, of ideas. Long before foreign ships appeared on its coasts, elaborate trade routes linked the interior to the ocean and the Arctic to the temperate zones of the Pacific Northwest. With trade came the circulation of motifs, techniques, and hybrid forms. Later, with the arrival of Russian, European, and American traders, this network expanded dramatically, producing both innovation and fracture in the artistic life of Alaska.

Inland Pathways and Coastal Currents

Archaeological finds show that obsidian from interior volcanic fields made its way to coastal communities, while shell ornaments from the Pacific drifted northward into Athabaskan settlements. These exchanges carried more than raw materials—they carried styles. The antler carvings of interior hunters sometimes echo the streamlined animal forms favored on the coast, suggesting shared symbolic vocabularies across distance.

For coastal groups like the Tlingit and Haida, trade voyages stretched south to present-day British Columbia and north toward the Arctic. Canoes loaded with eulachon oil, cedar bark, and carved goods became floating marketplaces. In return, copper, dentalium shells, and textiles from other regions entered Alaskan visual culture. Each item was more than a commodity: copper sheets, for instance, were cut into shield-like forms and imbued with ceremonial power, often depicted in totem pole reliefs and crest art.

A subtle but telling feature of this exchange lies in the rhythm of patterns. The woven designs of Chilkat blankets—complex, curvilinear forms—find distant echoes in Athabaskan quillwork, though adapted to different materials. Such parallels speak to a fluid artistic ecology where ideas traveled as readily as trade goods.

Russian Contact and New Iconographies

When Russian explorers and traders arrived in the 18th century, they introduced objects unfamiliar to local artisans: glass beads, iron tools, painted icons, and religious regalia. Beads in particular revolutionized decorative arts. Before their arrival, quills and natural pigments dominated. Suddenly, beadwork burst into clothing and ceremonial garments, producing dazzling surfaces that combined imported material with local design. Athabaskan women became masters of this new medium, creating floral patterns that spread widely in the 19th century.

The Russian Orthodox Church brought another profound layer. Icons, crosses, and church furnishings introduced a very different visual vocabulary—flat planes of color, gold leaf, and stylized sacred figures. Yet Alaskan carvers did not adopt them wholesale. In some villages, Orthodox iconography was adapted onto local materials: saints painted on sealskin, or church decorations carved with motifs that subtly echoed totemic imagery. This syncretism illustrates how external influence did not erase local tradition but instead encouraged complex hybrids.

One revealing story tells of a Tlingit carver who, when asked to decorate a Russian chapel, shaped the wood with the same tools he used for masks and clan crests. For him, the act of carving drew from ancestral skills, even if the subject was foreign. The resulting fusion was both Orthodox and unmistakably Alaskan.

Adaptation, Resistance, and Continuity

Not all exchanges were harmonious. The flood of foreign goods sometimes displaced local materials, and missionary efforts often sought to suppress traditional forms outright. Beadwork and embroidery, though adapted creatively, were sometimes promoted at the expense of older ceremonial practices. Meanwhile, the introduction of commercial trade in Native carvings turned sacred designs into market commodities, altering their meaning and use.

Yet adaptation often went hand in hand with resistance. When missionaries condemned masks, some artists carved miniature versions for discreet use, keeping alive the imagery of transformation. Others incorporated Christian symbols into traditional formats, asserting both survival and negotiation. In the gold rush era, carvers sometimes sold totem poles or masks to tourists, but in doing so they preserved carving techniques through generations that might otherwise have been silenced.

The story of Alaska’s hybrid art is therefore not one of simple assimilation but of layered negotiation. Imported beads sparkled on garments that still carried ancestral crests. Russian icons sat alongside carved amulets in homes. Commercial trinkets sold to outsiders supported carvers who continued to shape sacred poles for their communities.

In this tangled interplay, Alaskan art demonstrates a profound resilience: it absorbs, transforms, and redeploys the foreign without relinquishing its own core identity. Trade and exchange did not erase traditions but instead expanded the palette from which artists could draw, creating a hybrid visual language that still defines much of Alaska’s artistic character.

The Russian Orthodox Legacy

When Russian ships began to settle the Alaskan coast in the late 18th century, they carried not only traders and soldiers but priests, vestments, and icons. The Orthodox Church took root in Alaska earlier than in much of the continental United States, and its art—ornate, symbolic, steeped in centuries of Byzantine tradition—left an indelible mark on the region’s visual culture. Yet the story is not one of imposition alone; it is also about adaptation, negotiation, and unexpected fusion.

Icons and Sacred Space in a New Land

The arrival of Russian Orthodox missionaries coincided with the expansion of fur trade settlements, particularly in Kodiak and Sitka. Churches quickly became central architectural landmarks, their onion domes rising above Native villages. Inside, icons glowed in the dim northern light: saints painted with elongated faces, gold haloes, and an otherworldly stillness.

These images carried profound symbolic weight. For Orthodox believers, an icon was not a mere painting but a window into the divine—a physical channel through which the sacred entered the earthly world. When transplanted into Alaska, the icons maintained their power yet acquired new resonances. Local carvers sometimes crafted icon frames from driftwood or cedar, while the pigments used to restore older icons occasionally came from mineral deposits unique to the region. The divine thus entered not only through imported images but also through the very material substance of Alaska itself.

Churches, too, bore signs of local artistry. Wooden shingles, carved ornament, and the incorporation of animal motifs reflected the hands of Native carpenters who built them. In Sitka, where the Russian colonial presence was strongest, the cathedral became a focal point of cultural encounter: the icons were Russian, but the craftsmanship of the building was unmistakably Alaskan.

The Dialogue Between Orthodoxy and Native Tradition

Conversion to Orthodoxy was uneven and complex. Some communities embraced the faith, integrating it into existing systems of belief. Others resisted, holding ceremonies in secret while outwardly participating in church life. Artistic expression reflected this duality.

Beadwork, for instance, flourished under Orthodox influence. Imported glass beads became favored for decorating church vestments, altar cloths, and banners. Yet the designs often retained traditional floral or geometric motifs, so that the garments shimmered with a hybrid identity: part Orthodox liturgical attire, part continuation of Native aesthetic traditions.

There are accounts of saints painted with subtly localized features—slightly rounder faces, darker complexions—suggesting that artists were not simply replicating imported prototypes but reinterpreting them for local congregations. In some villages, crosses were carved with motifs recalling clan crests, blurring the line between Christian and ancestral symbolism. What might appear syncretic to outsiders was, for practitioners, a natural extension of their visual world.

Unexpectedly, Orthodoxy also preserved space for performance. Liturgical chanting, incense, and procession resonated with communities already familiar with ritual spectacle. Some anthropologists have suggested that the dramatic cadence of Orthodox worship appealed precisely because it mirrored aspects of Native ceremonial life. If so, the art of Orthodoxy in Alaska was not only visual but performative, reinforcing the theatrical dimensions already central to regional culture.

Enduring Symbols and Contemporary Reverberations

Even after the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867, the Orthodox Church remained deeply embedded in many communities, particularly among the Aleut, Alutiiq, and Yup’ik. Churches still stand in villages along the Kuskokwim River and on Kodiak Island, their modest wooden structures housing icons that may have traveled across Siberia centuries ago. These works continue to be venerated not as relics of colonial imposition but as living objects of faith, tied to family histories and communal identity.

At the same time, the Orthodox legacy has influenced contemporary Native artists in unexpected ways. Some draw on the visual language of icons—frontal figures, flattened planes, radiant color—to craft new works that speak both to ancestral traditions and modern concerns. Others engage critically, juxtaposing sacred imagery with motifs of colonization or ecological change. In every case, the Orthodox presence remains part of Alaska’s artistic DNA, an enduring reminder of cultural exchange at once fraught and fertile.

The Russian Orthodox legacy in Alaska is therefore not reducible to a story of domination. It is a narrative of resilience, accommodation, and layered meaning. The gold of the icons and the cedar of the forests now share the same sacred spaces, each transformed by the other. The result is an art history that does not separate faith from place but shows how belief itself becomes shaped by the land and the people who inhabit it.

The American Frontier and Territorial Visions

When the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867, it inherited not only a vast and little-known territory but also a region with complex artistic traditions already centuries old. Yet for many Americans at the time, Alaska was imagined less as a cultural landscape than as a frontier to be conquered, a wilderness of ice, gold, and opportunity. The art that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries reflected this vision—part documentary record, part mythmaking exercise, and part attempt to translate the immensity of the land into images intelligible to audiences thousands of miles away.

The Gold Rush Imagination

The discovery of gold in the Klondike in 1896 and in Nome a few years later triggered a flood of fortune-seekers and with them artists, illustrators, and photographers eager to capture the fever of the rush. Sketches published in illustrated newspapers showed miners trudging over snow-packed passes, dogs pulling sleds, and rough-hewn boomtowns sprouting from tundra. These images often exaggerated hardship or triumph, catering to readers hungry for tales of adventure.

Paintings, too, played their role. Artists such as Sydney Laurence, who settled in Anchorage in the early 20th century, turned Alaska’s mountains and glaciers into subjects of sublime grandeur. Laurence’s canvases of Mount McKinley (now Denali) glowed with dramatic light, their soaring peaks meant to rival the romantic landscapes of the Hudson River School. For many Americans who would never travel north, these paintings became the canonical images of Alaska—remote, heroic, and untouched.

But there was another layer. Gold rush towns attracted sign painters, engravers, and amateur sketch artists who documented everyday life: saloon interiors, makeshift theaters, dance halls. These works, less celebrated than Laurence’s vistas, provide invaluable glimpses into the improvisational culture of frontier settlements. The art of Alaska’s gold rush was thus not confined to romantic wilderness but extended into the gritty, chaotic fabric of human ambition.

Surveyors, Scientists, and the Aesthetics of Exploration

Beyond the gold fields, the U.S. government and scientific institutions dispatched surveyors, cartographers, and naturalists to chart the new possession. Many of these expeditions included artists tasked with rendering glaciers, coastlines, and wildlife. Their sketches and watercolors straddled the line between science and art, intended both as data and as illustrations for reports circulated to Washington and beyond.

One striking example is the work of William Healey Dall, an explorer and scientist whose field drawings of shells, birds, and landscapes combined meticulous observation with a quiet artistry. Such works rarely aimed for romantic flourish but instead sought accuracy. Yet in their very precision they conveyed a different kind of beauty: the elegance of detail, the drama of scale conveyed through careful line.

These expeditionary artists helped establish an aesthetic of Alaska as a place of scientific wonder. The glaciers were not only majestic; they were laboratories of geological time. The wildlife was not only picturesque; it was data to be catalogued and compared. The fusion of art and science in this period left a legacy still visible in the naturalist illustration traditions of Alaska today.

Wilderness as Symbol and Commodity

As Alaska’s image spread through paintings, photographs, and popular accounts, the idea of “the last frontier” took hold. Wilderness was framed not only as majestic but also as exploitable. Mining companies commissioned panoramic drawings of their claims, blending cartography with artistic flourish to attract investors. Tourist brochures later borrowed the romantic imagery of towering peaks and pristine rivers, selling Alaska as both a resource and a spectacle.

What emerges from this period is a striking paradox. On one hand, art celebrated the land as untouched, eternal, sublime. On the other, it served as propaganda for extraction and settlement, erasing the Native presence that had long animated the landscape with meaning. This selective vision of Alaska—wild yet empty, beautiful yet available—shaped American imagination for decades.

The territorial period left a mixed legacy: romantic paintings that still hang in Alaskan museums, photographs that remain staples of frontier lore, and visual stereotypes that continue to color perceptions of the region. Yet beneath these images, Native artists maintained their own practices, often unacknowledged in the mainstream narrative. The tension between frontier vision and Indigenous continuity remains one of the central dynamics of Alaska’s art history.

Photography and the New Image of Alaska

When cameras arrived in Alaska in the late 19th century, they transformed not only how the region was seen by outsiders but also how it was remembered by those who lived there. Photography became both a tool of exploration and a stage for performance, shaping Alaska’s image in ways that painting or carving never could. Unlike a totem pole or a mask, which carried meaning within a community, a photograph circulated across continents, projecting Alaska as wilderness, curiosity, or opportunity to audiences who might never set foot in the territory.

Ethnographic Lenses and Colonial Agendas

The earliest photographs of Alaska were often made by government expeditions or ethnographers. Their subjects were not mountains or glaciers but people—Native men and women posed in traditional clothing, often against neutral backdrops. These images were meant to serve as “types,” cataloguing human variation in much the same way as specimens of flora or fauna.

Such photographs reveal as much about the ambitions of their makers as about their subjects. Posed studio portraits of Inupiat families or Tlingit elders were frequently staged with props or costumes chosen by the photographer, not the sitter. The resulting images reinforced stereotypes of timelessness, suggesting cultures frozen outside of modernity. Yet behind the stillness of the photograph lies a more complicated story: many sitters understood the camera’s gaze and performed strategically, sometimes exaggerating or parodying the expectations of the photographer.

Traveling exhibitions of these photographs—shown in cities like Seattle, San Francisco, and New York—helped cement the image of Alaska as both exotic and primitive. The irony is that while Native art was flourishing in villages, the photographic record emphasized “vanishing” traditions, foreshadowing the paradox of preservation through misrepresentation.

Everyday Life and the Rise of Local Photographers

Alongside ethnographic images, photography also chronicled the boomtowns of the gold rush and the spread of American settlement. Streets lined with saloons, miners on frozen rivers, and sternwheelers navigating the Yukon became staples of frontier photography. Some images were clearly staged—miners pausing mid-swing with their picks—but others captured moments of unguarded vitality: a dogsled team lunging into snowdrift, children skating on an improvised rink.

Importantly, by the early 20th century, Alaskans themselves began to take control of the camera. Local studios in places like Nome and Fairbanks offered portraits to both settlers and Native families. These photographs disrupt the one-way gaze of ethnography, showing individuals dressed in the fashions of their choosing—sometimes traditional regalia, sometimes Western suits or hybrid combinations. They testify to the complexity of identity in a rapidly changing world.

One particularly telling series shows Athabaskan women wearing beaded parkas while holding parasols and books, objects associated with modern refinement. Such images upend the narrative of a people outside time, insisting instead on contemporaneity and adaptability.

The Camera as Landscape Painter

If painters like Sydney Laurence had established the romantic image of Alaska’s mountains, photographers soon amplified it with mechanical precision. Panoramic views of Denali, glacier calving scenes, and midnight sun vistas circulated widely in postcards and travel brochures. Railroads and steamship companies quickly recognized the marketing potential of these images, commissioning photographers to produce spectacles of scale and grandeur.

Yet the landscape photographs were not simply promotional; they also cultivated an aesthetic distinct to the region. The stark contrasts of snow and shadow, the way light refracted off ice, demanded new technical solutions. Exposure times had to be adjusted to prevent blank expanses of white, and negatives often required retouching to capture subtle tonal gradations. In solving these problems, photographers developed a visual language of Arctic and subarctic light that continues to influence Alaskan image-making today.

The unexpected twist is that many of these “untouched wilderness” photographs contain faint traces of human presence—canoes in the distance, fishing camps along riverbanks, trails cut through snow. While viewers in distant cities often overlooked these details, they testify to the lived reality that the land was never empty.

Photography remade Alaska into an image as much as a place. It documented, distorted, celebrated, and commodified. It provided scientific record while also serving as advertisement. And in the hands of local photographers, it became a tool for self-representation, a means of asserting agency against the tide of stereotypes. In the glassy surface of these early photographs lies the beginning of Alaska’s modern image—at once revealing and concealing, permanent yet selective.

Modernism on the Edge of the North

By the mid-20th century, Alaska had become both a state of mind and a laboratory for artists seeking new vocabularies of form. Modernism, with its hunger for distilled shape and radical experimentation, arrived not as a single movement but as a cluster of encounters—between visiting painters enthralled by northern light, regional artists carving out their own interpretations, and communities negotiating the pressures of modernization. The result was a body of work that stood at the edge of the continent and the edge of modern art, simultaneously peripheral and central.

Visiting Artists and the Seduction of Light

In the decades after World War II, Alaska attracted painters, photographers, and writers who sought in its landscapes a reprieve from metropolitan exhaustion. They found a visual environment that challenged the eye: light that lingered long past midnight, snowfields that dissolved shadows into pure geometry, and horizons so vast that perspective itself seemed unstable.

Some artists treated Alaska as an extension of the American tradition of wilderness painting, but others, steeped in abstraction, saw in its stark contrasts a chance to pursue form without narrative. Geometric blocks of ice, the blue-grey strata of mountain ranges, the flat glow of tundra at dusk—all became raw material for modernist experimentation. Works from this period reveal an oscillation: some hover close to realism, others verge on pure abstraction, as if the land itself were nudging artists toward reduction.

A telling anecdote survives from a visiting painter who confessed that he came north to “paint a mountain” but left with a canvas of only color fields—bands of grey, white, and faint blue. The mountain was gone, yet its immensity remained. In this way, Alaska’s landscape functioned less as subject than as catalyst, dissolving familiar forms into new modes of expression.

Regional Experiments and Emerging Centers

While visiting artists carried impressions back to Seattle, San Francisco, or New York, Alaskan cities like Anchorage and Fairbanks began to cultivate their own artistic communities. Galleries, universities, and community centers supported painters, printmakers, and sculptors who blended local imagery with modernist techniques.

Anchorage, in particular, became a hub after statehood in 1959. Exhibitions there often juxtaposed Native carving with abstract painting, inviting dialogue rather than segregation. For regional artists, modernism was not a rejection of place but a means of reinterpreting it. A printmaker might reduce a raven to angular lines, while a painter might translate the aurora borealis into swirls of color bordering on abstraction.

These experiments extended beyond the canvas. Ceramicists incorporated glacial forms into vessels, and architects tested modernist principles in buildings designed to withstand permafrost and earthquakes. The language of modernism thus spread across disciplines, adapted to the specific demands of Alaskan life.

The Push and Pull of Identity

The embrace of modernism in Alaska was never untroubled. On one side stood a desire for participation in the broader currents of 20th-century art, a refusal to be seen as provincial. On the other stood a growing awareness that art in Alaska carried different stakes—shaped by Native traditions, harsh environments, and the politics of statehood.

This tension produced some of the most intriguing work of the era. Artists experimented with hybrid forms: abstract canvases incorporating Tlingit design elements, sculptures that echoed both Inuit carving and minimalist reduction, photographs that blurred documentary and aesthetic intent. Critics outside the region often overlooked these experiments, but within Alaska they established a foundation for the contemporary scene that followed.

The paradox of the period is that modernism, often associated with urban centers, found fertile ground in a place still perceived as remote. The edges of the North became edges of artistic innovation. If earlier eras had cast Alaska as wilderness or frontier, modernist artists reimagined it as a space of formal exploration—a place where light, land, and tradition collided to produce images that felt both local and universal.

Contemporary Native Revivals

By the late 20th century, Alaska’s Native artists faced a dual challenge: reclaiming traditions that had been suppressed or commodified, and forging new expressions that spoke to contemporary realities. What emerged was not a simple return to the past but a revival movement marked by innovation, pride, and dialogue across generations. In carving workshops, weaving studios, and performance spaces, ancestral forms came alive again—sometimes replicated with fidelity, sometimes transformed in ways their makers a century earlier could scarcely have imagined.

Carving, Weaving, and the Power of Continuity

Carving was among the first traditions to surge back. In the 1970s and 1980s, master artists began training apprentices in totem pole construction, mask-making, and ivory carving. These revivals often took place in both village settings and urban centers, with community events accompanying the raising of new poles. The act of carving was not only about producing art but also about restoring communal memory.

Weaving, too, experienced a renaissance. The complex Chilkat blankets of the Tlingit, once nearly lost, were painstakingly studied and re-created by artists committed to reviving their intricate patterns of formlines and curvilinear design. Younger weavers adapted the technique to contemporary garments, creating robes and shawls that could appear in both ceremonial contexts and art galleries.

The persistence of these practices carried a message: Native art was not “historical” but living. A totem pole raised in 1980 did not replicate the 1880s; it reasserted presence in the face of erasure. Each new pole or robe carried not only aesthetic value but also an argument—that cultural continuity could be sustained despite centuries of disruption.

Innovation Within Tradition

Revival did not mean stasis. Many artists approached traditional forms as foundations for experimentation. A Yup’ik carver might create a mask echoing ancestral designs but intended for gallery display, incorporating new pigments or exaggerated proportions. A Tlingit printmaker could translate crest imagery into silkscreen, producing limited editions that circulated far beyond Southeast Alaska.

The innovations sometimes provoked debate within communities: Was a mask still sacred if sold to a collector? Did a screen-printed raven carry the same weight as a carved one? Yet these questions themselves testified to the vitality of the tradition, proving that it remained contested, relevant, and alive.

One particularly unexpected development came in jewelry. Gold and silver, mined and traded through colonial economies, were reworked into earrings and pendants bearing traditional motifs. The result was a paradox: colonial metals reshaped into emblems of cultural survival. Artists such as Denise and Donald Varnell became known for such work, collapsing boundaries between adornment, assertion, and fine art.

Preservation, Education, and the Next Generation

Institutional support also played a role. Museums and cultural centers began to partner with Native artists to provide workshops, exhibitions, and archives of design. The Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau, for instance, supported apprenticeships in weaving and carving, ensuring that techniques once transmitted in families could be learned by a broader community.

Schools incorporated art education that highlighted local traditions, allowing children to see their cultural forms not as relics in a museum but as part of their own lived environment. A new generation of artists grew up fluent in both Western and Native artistic vocabularies, able to navigate between carving knives and digital design programs.

This commitment to education underscored a central truth: revival was not nostalgia. It was forward-looking, an investment in continuity and adaptation. Each pole raised, each robe woven, each print edition produced was both a preservation of the past and a seed for the future.

The contemporary revival of Alaska Native art is not a sidebar in the state’s cultural history; it is one of its central stories. By reclaiming practices nearly silenced, artists reasserted not only aesthetic traditions but also sovereignty of memory and meaning. The art that emerged—rooted in ancestral form yet open to innovation—remains among the most compelling evidence that Alaska’s creative history is inseparable from the endurance of its Native peoples.

Alaska in the Global Contemporary Art Scene

By the turn of the 21st century, Alaska was no longer viewed solely as a frontier or a keeper of ancient traditions. Its artists were participating in conversations stretching from New York to Berlin, from Tokyo to Vancouver, while still grounding their work in the realities of northern life. The result was a body of contemporary art that defied easy categorization: simultaneously local and international, steeped in heritage yet restless for experimentation.

Crossing Borders and Biennials

Alaskan artists began to appear in biennials and major exhibitions across the globe. Their work carried with it the magnetism of a region often imagined in extremes—ice and fire, light and darkness, tradition and modernity. Yet these artists resisted being reduced to symbols. Instead, they used their participation in global circuits to complicate and expand narratives about the North.

Some showcased multimedia installations incorporating soundscapes of melting ice or recordings of traditional songs. Others presented video works juxtaposing village life with urban environments, creating a dialogue between the globalized art world and the intimate realities of Alaskan communities. The reception was often charged: audiences abroad were captivated by the imagery of glaciers and tundra, but the artists themselves emphasized human presence, memory, and resilience over exotic landscapes.

Unexpectedly, the biennial stage also became a space where Alaska’s Native artists could engage in dialogue with Indigenous creators from New Zealand, Scandinavia, or the Arctic Circle. Shared themes of land, sovereignty, and cultural survival produced conversations that transcended geography, situating Alaska within a wider global Indigenous avant-garde.

Negotiating Identity and Market

Global recognition brought opportunities, but also tensions. Collectors and curators often sought work that emphasized “Alaskan-ness,” pressuring artists to conform to preconceived ideas of Native tradition or Arctic spectacle. Some resisted by producing deliberately ambiguous work—abstract paintings with no reference to place, or conceptual pieces that dismantled clichés about the wilderness. Others embraced the market but subverted its expectations, embedding biting humor or critique within apparently traditional forms.

A telling example can be found in sculpture that echoes the form of a ceremonial mask but is made from industrial plastic, challenging the idea that authenticity must be tied to ancient materials. Similarly, photography series depicting snowmobiles abandoned in the tundra complicate romantic notions of timeless subsistence, revealing the entanglement of technology, waste, and survival.

For many artists, the challenge was not whether to be “traditional” or “contemporary” but how to navigate a space where both identities were demanded, sometimes in contradiction. The resulting art speaks precisely to this tension—works that feel grounded in Alaska yet also unsettle the expectations of what “Alaskan art” should look like.

Collaboration, Technology, and New Directions

The global contemporary moment also encouraged collaboration across media. Musicians worked with visual artists to stage immersive performances; dancers collaborated with projection designers to transform stories into digital landscapes. The Anchorage Museum and other institutions facilitated these cross-disciplinary experiments, creating platforms where the boundaries between art forms blurred.

Technology, too, became central. Video installations captured shifting light over glaciers, while digital design programs allowed young artists to rework traditional motifs into animation or virtual environments. The internet expanded Alaska’s reach, enabling artists to share work instantly with global audiences while also connecting with one another across vast distances within the state itself.

One surprising direction has been the embrace of environmental art. Installations using ice blocks, driftwood, or even permafrost soil have been staged in both local and international contexts, deliberately ephemeral works that mirror the fragility of Arctic ecosystems. These projects draw on both global concerns about climate change and local experience of environmental transformation, making Alaska’s art a potent voice in one of the central debates of our time.

Alaska’s presence in the global contemporary art scene is not a matter of exporting curiosities from the edge of the map. It is about artists who stand with one foot in their villages and another in international galleries, who draw equally from ancestral traditions and avant-garde experimentation. Their work insists that Alaska is not peripheral but central to the story of art today, a place where the local and the global, the ancient and the experimental, continually collide to generate new forms of expression.

The Aesthetics of Survival and Environment

In Alaska, survival has always been inseparable from art. The clothing that shields against subzero cold, the tools that carve a path through ice, the shelters that withstand storms—all carry aesthetic choices as well as practical necessity. In the contemporary period, this intertwining of environment and creativity has taken on new urgency, as artists respond not only to the challenges of living in the North but also to the accelerating transformations of climate change.

Clothing as Art, Survival as Beauty

Traditional Alaskan garments—parkas, mukluks, mittens—were never purely utilitarian. Their construction required extraordinary technical skill, from sewing waterproof seams in seal gut to weaving intricate patterns from sinew or grass. Yet beyond function, these garments carried symbolic meaning. A parka adorned with beadwork announced family identity and artistry; a dancer’s regalia transformed survival gear into ceremonial splendor.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, artists began to present such garments in galleries, asking audiences to see them not only as ethnographic artifacts but as works of design. The cut of a hood, the arrangement of beads, the interplay of fur and fabric—each detail reveals an aesthetic system attuned to both environment and identity. Some contemporary designers reinterpret these traditions for fashion shows, merging sealskin with modern textiles or translating beadwork into couture silhouettes. These hybrid creations remind us that survival and style are not opposing categories but deeply interwoven in Alaskan life.

One unexpected example comes from garments made of fish skin. Long practiced in coastal communities, the technique has been revived by artists who treat salmon skin as both a durable material and a symbolic statement, its shimmering surface echoing the rivers that sustain life. What was once a pragmatic solution has become a provocative form of environmental commentary.

Responding to Melting Ice and Shifting Seasons

As climate change reshapes Alaska’s landscapes, artists have turned to the environment itself as subject and medium. Installations of melting ice blocks, filmed time-lapses of retreating glaciers, and sound pieces capturing the crack of permafrost thaw all translate environmental anxiety into sensory experience. These works are not simply about documenting loss but about confronting the fragility of ecosystems that have defined Alaskan life for millennia.

For some, the approach is elegiac: paintings of diminished sea ice or vanishing caribou herds serve as memorials. For others, it is confrontational: sculptures made of discarded oil drums or mining debris highlight the contradictions of resource extraction in a fragile environment. Performance artists have staged pieces in remote landscapes, their bodies wrapped in reflective material, becoming temporary markers of human vulnerability against vast natural forces.

The thread uniting these practices is the recognition that environment is not backdrop but protagonist. Art becomes a dialogue with melting rivers and shifting skies, an attempt to reckon with forces too immense to control yet impossible to ignore.

Art, Activism, and Ecological Imagination

The environmental turn in Alaskan art often slides into activism, though not always in conventional forms. Rather than slogans, artists use visual provocation to spark reflection: a gallery filled with sculptures made from eroding whale bone, or a mural depicting salmon transforming into circuitry, warning of ecological imbalance in the age of technology.

Three recurring strategies stand out:

- Ephemerality, using materials like ice or snow that disappear, mirroring ecological fragility.

- Juxtaposition, combining natural and industrial forms to expose tension between tradition and modernity.

- Community participation, inviting viewers to add to installations or rituals, reinforcing shared responsibility.

These strategies underscore that environmental art in Alaska is not merely about representation but about process and engagement. By emphasizing impermanence, contradiction, and collectivity, artists align their practice with the ecological realities of the North.

In Alaska, art and environment remain inseparable, bound by necessity and imagination. From bead-adorned parkas to installations of thawing permafrost, creativity arises in response to the elemental fact of survival. Today, as climate change unsettles the very ground beneath villages and glaciers, Alaskan artists translate that vulnerability into forms that resonate far beyond the region. Their work insists that to live in the North is to live in constant negotiation with forces larger than oneself—and that this negotiation is, at its core, an act of art.

Museums, Markets, and the Politics of Display

If Alaska’s art has long been forged in villages, forests, and coasts, it has also found itself reframed in museums, sold in markets, and circulated as commodity. The act of placing a mask behind glass or a totem pole in a gift shop alters meaning as profoundly as the carving or weaving itself. The politics of display—who controls, who interprets, who benefits—has become one of the most contested dimensions of Alaskan art history.

Institutions of Collection and Interpretation

From the late 19th century onward, anthropologists, missionaries, and traders removed countless works from Native communities, sending them to museums in Seattle, New York, and beyond. These objects—ceremonial masks, carved poles, beaded garments—were often treated as “ethnographic specimens” rather than as living works of art. Context was stripped away, replaced by labels that emphasized utility or exoticism.

By the mid-20th century, Alaska’s own museums began to emerge, offering new possibilities. The Alaska State Museum in Juneau and the Anchorage Museum positioned Native art not as relic but as cultural centerpiece. Exhibitions juxtaposed historical works with contemporary creations, emphasizing continuity rather than rupture. Yet even within Alaska, questions persisted: who wrote the labels, who curated the shows, whose voice defined authenticity?

In recent decades, partnerships between museums and Native organizations have sought to shift authority. Programs invite elders and artists to interpret collections, bringing ancestral knowledge back into spaces where it had been excluded. Some institutions now host ceremonial use of artifacts, allowing objects once frozen in display cases to re-enter cycles of performance, even if briefly.

The Market and the Allure of Authenticity

Alongside museum display, a parallel story unfolds in markets. From early trading posts to modern galleries in Anchorage and tourist shops in Juneau, Native art has long been bought and sold. Ivory carvings, beadwork, and masks became prized souvenirs, their value often tied to ideas of authenticity.

But authenticity itself proved slippery. A miniature totem pole made for tourists might have little ceremonial function yet required extraordinary carving skill. A beaded wallet or bracelet, though destined for sale, carried motifs drawn from deep tradition. For many artists, market work was not a betrayal but a livelihood, a way to sustain families while preserving techniques.

At the same time, the commodification of sacred forms provoked unease. Was a mask still spiritual if displayed in a hotel lobby? Did mass-produced designs dilute meaning? Debates over appropriation and commercialization intensified, especially when non-Native manufacturers began producing knockoffs marketed as “Alaskan.” Federal laws, such as the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, attempted to protect authenticity, but enforcement remained uneven.

This tension between economic necessity and cultural responsibility continues to shape artistic practice. For some, the market is a threat; for others, it is a stage for asserting presence and skill. Many artists navigate both positions at once, creating works that satisfy commercial demand while reserving sacred forms for community use.

Repatriation and the Return of Voice

Perhaps the most transformative development in recent decades has been the movement for repatriation. Under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and related policies, museums have returned ceremonial objects and human remains to Alaskan communities. These acts are more than legal gestures; they are reanimations of artistic lineage. When a mask is danced again after a century in storage, or when clan regalia returns to a house where it once held meaning, art history becomes present tense.

Some repatriated works remain in community museums or cultural centers, accessible to descendants and used in ceremonies. Others inspire new creations, as carvers and weavers study ancestral forms and carry them forward. The process also reshapes museums themselves: curators are compelled to cede authority, to acknowledge that these works are not static objects but active participants in living cultures.

The politics of display thus remains unsettled, an ongoing negotiation between preservation, interpretation, and renewal. Museums can be sites of erasure or of resurgence, markets can exploit or sustain, and authenticity can be both a burden and a shield. What is certain is that Alaska’s art, once displaced and silenced, is increasingly finding ways to speak again—in galleries, in homes, in festivals, and in the land where it was first created.

Personalities and Pioneers

While much of Alaska’s art history is rooted in collective traditions, certain figures stand out for the ways they carried techniques forward, redefined genres, or opened new doors for recognition. These individuals, whether Native or non-Native, traditionalists or modernists, became bridges between worlds—often at personal cost. Their stories offer glimpses of how art in Alaska has always been more than objects: it is also the lives and choices of those who shaped them.

Master Carvers and Cultural Guardians

Among the most celebrated are carvers who ensured that monumental traditions did not vanish under missionary suppression and cultural upheaval. Nathan Jackson, a Tlingit master carver born in 1938, raised pole carving to international prominence. His works stand not only in Southeast Alaska but in museums and public spaces around the world. Yet Jackson never treated carving as solitary genius; he insisted on apprenticeship, teaching younger generations the technical rigors of formline design and the ethical weight of working with clan imagery.

Similarly, Haida artist Robert Davidson, though born in British Columbia, profoundly influenced Alaskan carving through his revival of Haida pole raising in the 1960s. His bold reinterpretations of traditional formline design—often pared down to almost abstract compositions—showed that heritage could be both preserved and reimagined. Davidson’s example resonated across borders, encouraging Alaskan artists to balance fidelity to tradition with personal innovation.

One could add ivory carvers of the Bering Strait region, whose small but intricate works distilled centuries of skill. Artists like Susie Silook have expanded the tradition, producing carvings that address themes of identity and resilience while retaining the elegance of ancestral miniature sculpture. These carvers, in different mediums, stand as guardians of continuity, proving that even amid disruption, art remains a vessel of endurance.

Pioneers of the Northern Landscape

On the non-Native side, painters such as Sydney Laurence became synonymous with Alaska’s wilderness image. Born in Brooklyn in 1865, Laurence moved to Alaska around 1904, where he devoted himself to rendering Denali and other landscapes with atmospheric drama. His canvases, suffused with glowing light and towering peaks, helped define Alaska for audiences far beyond its borders. Though his vision often reflected the frontier myth, Laurence’s technical mastery and commitment to Alaska anchored him as a pioneer of regional painting.

Another notable figure was Eustace Ziegler, an Episcopal missionary-turned-painter who settled in Cordova in the early 20th century. His work depicted miners, fishermen, and Native villagers with a mixture of documentary observation and romantic idealization. While not free of the biases of his time, Ziegler’s art broadened Alaska’s painted repertoire beyond wilderness to include human life on the frontier.

These painters helped secure Alaska a place in the broader narrative of American landscape art, though their visions often eclipsed Native perspectives. Their legacies today are received with ambivalence: admired for their craft, critiqued for their erasures. Yet they remain central to understanding how Alaska was visually imagined in the American consciousness.

Contemporary Voices and Global Recognition

In recent decades, new pioneers have emerged, expanding Alaska’s artistic reach. Artists like Da-ka-xeen Mehner, of Tlingit and Irish heritage, create installations and photography that confront questions of identity, family, and cultural survival. His works juxtapose traditional regalia with contemporary settings, challenging static notions of heritage.

Other contemporary figures include Sonya Kelliher-Combs, who blends organic materials like walrus gut and animal fur with synthetic substances such as resin and nylon. Her work, both delicate and unsettling, meditates on skin, memory, and the fragility of cultural continuity. Through such material experimentation, Kelliher-Combs situates Alaskan art within global contemporary dialogues while remaining deeply rooted in northern realities.

These personalities, diverse in background and approach, share a common thread: they act as translators between traditions and audiences, between Alaska and the world. Their pioneering lies not only in innovation but in insistence—that Alaska is not marginal but central, that its art belongs in both community ceremonies and international exhibitions.

Futures of Alaskan Art

Alaska’s art has always thrived on negotiation—between tradition and experiment, isolation and exchange, necessity and imagination. Looking forward, its trajectory seems poised to accelerate along multiple paths, fueled by technology, education, and a generation of artists who see no contradiction between carving cedar and coding digital environments. The future of Alaskan art, if one can glimpse it, is one of multiplicity: rooted in ancestral ground yet expanding into unexpected domains.

Digital Practices and New Platforms

The digital turn has opened avenues unimaginable to earlier generations. Young Alaskan artists increasingly work with video, animation, and virtual reality, drawing on the region’s unique imagery to create immersive environments. A raven crest might be reimagined as a motion graphic, or the shifting aurora borealis translated into algorithm-driven projections. These works circulate not only in galleries but also online, reaching audiences far removed from the northern landscape.

Social media has also become a tool of visibility and connection. Artists in remote villages can share carvings or beadwork with global networks, selling directly to collectors and bypassing traditional markets. This democratization of distribution offers both opportunity and risk: it enables broader recognition but also exposes artists to appropriation and misrepresentation. The balance between openness and protection will be a defining challenge of the digital era.

Unexpectedly, some digital works carry the spirit of traditional ephemerality. Just as masks were once burned after ceremonies, certain online projects exist only temporarily—vanishing installations in virtual space that echo the cycles of renewal central to Native cosmologies. In this way, technology does not erase tradition but becomes another vessel for its persistence.

Youth, Education, and the Continuity of Skill

Educational initiatives across Alaska are investing in art as both cultural preservation and creative innovation. Village schools host carving programs, urban high schools teach digital media alongside beadwork, and universities in Anchorage and Fairbanks offer expanded art curricula that encourage students to engage with both local heritage and global movements.

The emphasis on intergenerational transmission remains central. Elders teach weaving and carving, while younger artists introduce digital tools. This two-way exchange ensures that tradition is not simply handed down intact but adapted in dialogue with new technologies and sensibilities. For many young Alaskan artists, identity is not a binary of old and new but a fluid space where a Chilkat pattern can coexist with graffiti, or where hip-hop beats accompany mask dances.

The vitality of youth engagement suggests that Alaska’s art will continue to evolve with energy, refusing to be fixed in static categories. What once risked fading is now finding fresh voices, carried forward by those unafraid to blend reverence with reinvention.

Speculative Trajectories

Looking further ahead, several trajectories seem likely to shape the future of Alaskan art:

- Environmental urgency: As climate change intensifies, artistic responses will deepen, with works that both mourn and mobilize. Ice, permafrost, and salmon may become even more central motifs.

- Global collaboration: Exchanges with Arctic and Indigenous artists worldwide will expand, situating Alaska within networks of shared experience and innovation.

- Blurring of boundaries: The line between fine art, performance, design, and activism will continue to dissolve, producing hybrid forms difficult to categorize but rich in resonance.

What unites these trajectories is an insistence that Alaska is not peripheral. Its art is not frozen in time or relegated to ethnographic display. Instead, it is restless, evolving, and fully enmeshed in the questions facing the 21st century: identity, environment, technology, and continuity.

The future of Alaskan art, then, is not a single narrative but a constellation of possibilities. From cedar poles to digital projections, from beadwork to performance, it will continue to chart paths that are at once deeply local and unmistakably global. In its capacity to transform necessity into beauty, and memory into invention, Alaska’s art will endure—not as a relic of the past but as a living force that shapes and surprises the future.