Paul Gauguin was born on June 7, 1848, in Paris, France, into a life that seemed destined for the conventional. Early on, he entered the world of finance and became a stockbroker in the 1870s, a path that supported his family but left him yearning for something deeper and more expressive. During these years, he married Mette-Sophie Gad in 1873, and they raised five children together, but Gauguin’s passion for art grew stronger as time went on. His friendships with Impressionist painters, including Camille Pissarro, encouraged him to pursue art more seriously, and he began painting in his spare time, gradually leaving his financial career behind.

In the late 1880s, Gauguin became increasingly disillusioned with European society’s focus on material success and social conventions. By 1886, he made the decisive break from Mette and his life in Denmark, sending his family away and dedicating himself fully to his artistic ambitions in France. He embraced Symbolism, a movement that valued imagination and spirituality over mere naturalistic representation, and this shift reflected his desire to express deeper emotional and spiritual truths in his art. Part of this drive led him to seek inspiration in places and cultures untouched by Western industrialization. His aim was not merely to paint landscapes but to explore existential questions through the lens of “primitive” cultures, as he saw them.

In 1891, after a successful auction of his works and encouragement from fellow artists, Gauguin left for Tahiti on April 1, hoping to escape what he called “everything that is artificial and conventional.” He imagined a paradise where art and life fused seamlessly in an untouched natural world. Upon arrival, he found a society already altered by French colonial influences, yet this only intensified his imaginative reconstruction of its culture. The island stirred in him a yearning for spiritual and creative renewal, and the vibrant colors, lush landscapes, and indigenous traditions deeply influenced his evolving artistic vision.

During these years, Gauguin’s personal life remained tumultuous; he entered relationships with local women, some of whom were very young by Western standards, a fact that modern critics scrutinize intensely. Nevertheless, Tahiti offered him subjects, colors, and ideas that he would explore throughout his career, particularly in works like Mahana no atua, which synthesized memory and imagination rather than documented real rituals. His first Tahitian period lasted until 1893, after which he returned to Paris, energized and determined to share his new artistic language with the world.

From Stockbroker to Seeker: Gauguin’s Life Before Tahiti

Gauguin’s transition from financial professional to full-time artist was neither smooth nor simple. Initially earning his living in the structured world of Parisian finance, he painted in his spare hours, often guided by the encouragement of his artistic peers. His marriage to Mette-Sophie and the responsibilities of fatherhood weighed on him, yet also fueled his desire to break free from bourgeois life. This transformation set the stage for his radical relocation to Tahiti in pursuit of artistic and spiritual authenticity.

Tahiti as Paradise Lost and Found

Gauguin’s arrival in Tahiti in 1891 was laden with romantic expectations of an untouched Eden where he could immerse himself in what he imagined would be a pure, uncolonized culture. He expected to find an indigenous tradition rich in ancient customs and spirituality, the sort of “primitive” foundation he believed could inform a new artistic perspective. However, he was met with a society deeply influenced by French colonial presence, Missionary Christianity, and commercial change. The reality was far removed from the Edenic fantasies he harbored, though this mismatch between expectation and reality became a fertile ground for his creative imagination.

Despite these contradictions, Gauguin embraced the landscape, people, and sensory experiences of the South Pacific. He became fascinated with local dances, traditional lore, and the rhythms of daily life, even as colonial authorities increasingly regulated indigenous practices. His portrayal of Tahitian culture often blended real observation with imagined rituals, driven more by his artistic symbolism than ethnographic accuracy. The lush colors of tropical flora and the expressive potential of the human form in this environment revitalized his canvases and informed his shift toward bold, simplified shapes and flat planes of color.

While in Tahiti, Gauguin lived modestly, his health and finances frequently precarious, yet his artistic output was prolific. He developed close relationships with local people, which influenced his figures and compositions, though these relationships were often imbalanced and controversial by today’s ethical standards. His personal life on the island was both a source of intimate inspiration and a subject of later criticism, as his lifestyle and choices were intertwined with the colonial context. These experiences, however imperfect, infused his work with an intensity and immediacy that resonated with European audiences upon his return.

Ultimately, Tahiti offered Gauguin not a static cultural archive, but a sensory and emotional palette from which he drew imaginative scenes that stirred European artistic communities. He departed Tahiti in 1893, returning triumphantly to Paris, where he continued to refine his vision of the South Seas through works like Mahana no atua—paintings that were less about documentation and more about the spiritual resonance he sought to convey.

Culture Clash and Artistic Rebirth

Though Tahiti was not the untouched paradise Gauguin dreamed of, it catalyzed his transformation into a defining figure of Post-Impressionism. He blended observed cultural elements with invented symbolism to capture the spiritual essence he sought. The ocean’s vivid blues, tropical light, and rhythmic dances all became elements he reconfigured into bold, emotive compositions. This period reshaped his artistic identity and prepared him for collecting his impressions into paintings once back in Europe.

The Making of Mahana no atua (Day of the God)

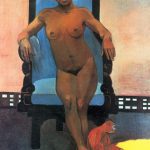

Mahana no atua was painted in 1894 after Gauguin returned to Paris from his first stay in Tahiti. Though physically removed from the island, his mind remained absorbed in its colors, myths, and rituals. He created the work from memory and imagination, not from direct observation, blending symbolic intention with stylistic boldness. Executed in oil on canvas, the piece measures 68.4 × 91.5 cm and is now housed in the Art Institute of Chicago.

The painting depicts a beach scene, its focal point being a large idol of the goddess Hina placed prominently in the center. Around her are Tahitian women, shown in brightly colored garments or partially nude, participating in activities that suggest religious reverence or ceremony. Despite the implication of sacred ritual, no actual Polynesian practice is being documented here. Rather, Gauguin constructs a spiritual tableau out of his own vision of paradise and cultural yearning.

A 1894 Parisian Product of Tahitian Memory

While rooted in the aesthetics of Polynesia, the painting was entirely a Parisian creation. Gauguin had returned to the French capital disillusioned with the Western world but driven to share his new symbolic language. Mahana no atua was an attempt to distill what he felt Tahiti represented—purity, spiritual order, and sensual truth. It was never meant as an ethnographic record, but rather a personal, even mystical, reinterpretation.

Gauguin divided the composition into horizontal zones, creating a rhythmic, almost musical structure of space and gesture. The warm, unnatural colors flatten perspective and increase the painting’s dreamlike intensity. Forms are simplified, and figures appear timeless, frozen in symbolic postures. This approach was crucial in his break from Impressionism and anticipated the direction modern art would soon follow.

Symbolism and Spirituality in the Composition

The most immediately striking feature of Mahana no atua is its central idol, which Gauguin presents as a carved figure of the goddess Hina. Hina was not typically portrayed in such a visual form in Tahitian tradition, but Gauguin reimagined her as the spiritual heart of the scene. She is flanked by two worshippers, their arms raised in what may be prayer or dance, forming a triangle that radiates symbolic energy. The carved figure functions as an anchor around which the other elements revolve.

Behind and around Hina, figures appear engaged in communal or ritualistic acts. To one side, women gather in repose or carrying offerings; to the other, dancers perform the upaupa—a sensual movement once condemned by colonial authorities. These groupings suggest a sacred observance, though no known Tahitian religious practice looked quite like this. Gauguin drew from imagination, selectively borrowing and altering visual elements to suit his symbolic vision.

Three Figures, Three Stages of Life

In the foreground, three women bathe near the shoreline, arranged in a progression that many scholars interpret as a cycle of life. The figure on the left lies curled, fetal-like, symbolizing birth. The central figure, upright and strong, represents life in its prime. The final figure reclines, face turned down, perhaps embodying death or transcendence. The water they rest in becomes a metaphorical passage, connecting their symbolic journey.

This triad reflects Gauguin’s engagement with themes of existence beyond the visible world. By distilling life into three archetypal forms, he moves beyond narrative into philosophy. Their placement in the calm shallows below the religious scene emphasizes their universality—they are not Tahitian per se, but human. This foreground turns the painting inward, inviting viewers to reflect on their own passage through life’s stages.

Controversy and Colonial Romanticism

In recent decades, Mahana no atua and Gauguin’s broader Tahitian oeuvre have faced growing criticism for romanticizing and distorting indigenous cultures. The painting constructs an imagined ritual that speaks more to Gauguin’s fantasies than any real Polynesian practice. His tendency to treat Tahitian society as a spiritual antidote to European materialism has drawn accusations of colonial idealization. These critiques call attention to how Western artists often appropriated “exotic” cultures for personal expression.

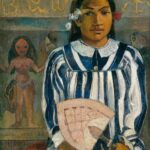

Gauguin’s private life intensifies these concerns. While in Tahiti, he entered relationships with several underage girls, most notably Teha’amana, who was just 13 at the time. These relationships, though normalized under colonial systems of the era, are now rightly viewed as exploitative. Combined with his abandonment of his wife and children in Europe, this behavior has prompted difficult reassessments of his legacy. The man behind the masterpiece is as complex as the work itself.

Yet defenders argue that Gauguin sought genuine spiritual and artistic renewal, not merely escapism. His symbolic use of myth, color, and form helped break the boundaries of traditional painting. Many of the movements that followed—Fauvism, Primitivism, and Expressionism—owe a direct debt to Gauguin’s Tahitian visions. Whether one praises or critiques him, his role in reshaping modern art is undeniable.

Gauguin’s Idealization vs. Indigenous Reality

The friction between authenticity and imagination defines Mahana no atua. Gauguin invented a world of ritual and meaning that may never have existed, yet which resonates with emotional truth. This gap challenges viewers to consider what art should strive for—fact or feeling. Ultimately, the painting reflects as much about Western longing as it does about Tahitian life.

Legacy of Mahana no atua in Art History

Mahana no atua is widely regarded as a keystone of Paul Gauguin’s late work and one of the defining images of Post-Impressionist Symbolism. It captures his mature style, characterized by flattened shapes, vivid color fields, and deeply symbolic content. These visual strategies departed from the realism of Impressionism and introduced abstraction as a means of spiritual expression. In doing so, Gauguin laid the groundwork for movements that would shape 20th-century art.

The painting’s impact extended far beyond Gauguin’s lifetime. Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and other modernists drew directly from his simplified forms and expressive use of color. His innovations offered a new visual language that emphasized emotional truth over surface accuracy. The ripple effect of this approach can be seen in both European avant-garde painting and the rise of non-objective abstraction.

A Modernist Milestone and Museum Treasure

Today, Mahana no atua holds pride of place at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it remains one of the most visited and studied works in the collection. Its unique fusion of sensuality, mysticism, and innovation continues to captivate viewers. Art historians still debate its meanings, but few deny its power. As a cultural artifact, it sits at the intersection of genius and controversy.

The painting is a visual summation of Gauguin’s worldview—complex, contradictory, yet arrestingly beautiful. It draws the viewer into a dream of spiritual communion, where gods, humans, and nature intertwine. Whether read as fantasy, confession, or critique, Mahana no atua continues to inspire and provoke. Its legacy is a living conversation, not a closed chapter.

Gauguin Revisited in the 21st Century

As art history evolves, Mahana no atua remains a centerpiece in discussions about cross-cultural influence and artistic ethics. Museums, scholars, and educators now approach Gauguin’s work with more context and caution than in previous decades. Rather than dismissing or uncritically praising him, many institutions strive for balance—acknowledging his technical brilliance alongside his personal and cultural flaws. This holistic approach allows for richer understanding.

Exhibitions in recent years have often paired Gauguin’s works with voices from Polynesian communities or post-colonial scholars. This framing provides contrast to the imagined narratives within the paintings. It also restores agency to the cultures Gauguin interpreted, offering viewers more than one lens through which to experience his art. These curatorial choices reflect an ongoing effort to engage responsibly with the past.

Rethinking the Artist, Reframing the Work

Critics and art lovers alike are now re-evaluating what Gauguin’s legacy should be. Can we separate the artist from the art? Should we? These are the questions institutions and audiences ask when standing before Mahana no atua. The painting doesn’t offer answers—but it forces viewers to look deeper.

Ultimately, Mahana no atua stands as both masterpiece and moral puzzle. It exemplifies the beauty and the burden of Western art’s global encounters. The painting remains, as Gauguin surely intended, a myth in paint. But it is our task to interpret that myth with honesty, empathy, and wisdom.

Key Takeaways

- Gauguin painted Mahana no atua in 1894 during a Parisian period of reflection and reinvention.

- The work blends Tahitian-inspired imagery with symbolic storytelling, not ethnographic accuracy.

- Central elements like the goddess Hina and the trio of bathers reflect themes of life and spirituality.

- The painting is both celebrated for its innovation and critiqued for its romanticized view of Tahitian life.

- Its influence shaped modern art movements and remains strong today.

FAQs

- What does “Mahana no atua” mean?

It translates from Tahitian as “Day of the God,” referring to the spiritual theme of the painting. - Where did Gauguin paint Mahana no atua?

He painted it in Paris in 1894, drawing from memories of Tahiti. - What is the painting’s size and medium?

It is an oil on canvas, measuring 68.4 × 91.5 cm. - Where is the painting located today?

It is part of the permanent collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. - Why is Gauguin controversial?

He is criticized for exploiting Tahitian culture and forming relationships with underage girls during his time there.