Gargas Cave, or Grotte de Gargas, is nestled in the limestone hills near the village of Aventignan in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of southwestern France. This important prehistoric site sits at an altitude of approximately 560 meters (1,837 feet) in the foothills of the Pyrenees. Its geographical placement made it accessible to prehistoric peoples traveling through the region, likely following game herds and seasonal routes. The entrance to the cave is set into a rocky outcrop and leads to a vast network of chambers that extend over 700 meters into the mountain.

The cave was first documented in the modern era in 1906 by French physician and prehistorian Félix Regnault, but more detailed archaeological investigations began with the renowned Abbé Henri Breuil and Émile Cartailhac. Their work laid the foundation for further study into Upper Paleolithic art. Today, the cave is managed by French heritage authorities and open to limited public visitation. It is currently on the UNESCO Tentative List for World Heritage designation due to its exceptional preservation of Ice Age art and human activity.

Key Stats of Gargas Cave:

- Location: Aventignan, Hautes-Pyrénées, France

- Altitude: ~560 meters above sea level

- Cave Length: ~700 meters of explored chambers

- First Study: 1906 (Félix Regnault), detailed in 1911

- Public Access: Guided tours permitted, with conservation measures

- UNESCO Status: On Tentative List (since 2002)

Geological and Environmental Context

Gargas Cave was formed within Cretaceous limestone deposits laid down more than 100 million years ago. Over millennia, water erosion carved the natural galleries, chimneys, and chambers that would eventually become shelters and sacred spaces for Upper Paleolithic humans. The thick limestone layers have helped preserve the cave’s interior artwork from erosion, light exposure, and major environmental shifts.

During the time the cave was inhabited and decorated—estimated to be between 27,000 and 25,000 BC—the region experienced extremely cold conditions, characteristic of the Last Glacial Maximum. The cave provided warmth, shelter, and stable conditions for Ice Age hunters. It’s likely that the surrounding area supported large game, such as woolly mammoths, reindeer, and ibex, which are frequently represented in cave art from this era. The caves’ elevation and visibility from nearby valleys would have made it an ideal waypoint or gathering site.

The high mineral content in the cave walls, combined with low humidity and stable temperatures, has been instrumental in the survival of the fragile pigments used in the hand stencils and animal paintings. These environmental factors have allowed researchers to study Gargas in nearly the same condition it was in when it was last visited by humans over 25,000 years ago.

What’s Inside — The Artworks of Gargas

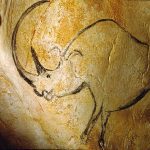

Gargas Cave is best known for its remarkable collection of negative handprints, which appear in vibrant red, deep black, and rare ochre-yellow pigments. These hand stencils number over 200 and are among the most haunting and mysterious in all of prehistoric Europe. They cover the walls and ceilings of multiple chambers, clustered in dense panels that suggest group activity or ritual significance. In addition to hand stencils, the cave also contains a wide array of animal depictions including bison, ibex, horses, and mammoths, though these are fewer in number and often less visually prominent than the hands.

The artists used natural mineral pigments — primarily iron oxide (red ochre) and manganese dioxide (black) — and applied them using various methods. The most common was a blowing technique, where pigment was sprayed over a hand pressed against the wall, creating a stenciled negative image. This was likely done using hollow bones or reeds as rudimentary airbrushes, a method confirmed through experimental archaeology. Some artworks also include abstract signs, including dots, bars, and claw-like patterns whose meaning remains unknown.

Studies have shown that the animal drawings were likely made before the hand stencils, based on pigment composition and wall placement. This layering has helped establish a relative chronology within the cave, although all the art likely falls within the Aurignacian to early Gravettian periods, roughly between 28,000 and 25,000 BC.

The Negative Handprints — What They Are

Creation Technique of Negative Hand Stencils

The most distinctive artworks in Gargas Cave are its negative hand stencils—clear outlines of human hands created by spraying pigment around them. This technique has been well documented in archaeological research and replicated in controlled experiments. The individual would place their hand flat against the rock surface and blow pigment—likely mixed with saliva or water—through a hollow reed, bone, or directly from the mouth to create a halo-like outline. This simple yet effective method enabled the creation of stark, durable images.

Close examination shows that the majority of stencils are left hands, suggesting that artists were primarily right-handed. This is consistent with general human biology and supports similar findings at other European cave sites. The prints vary in size, with some clearly belonging to children as young as five years old, and others being adult-sized. This diversity points toward communal involvement in the creation of these images, rather than solitary or elite practice.

Gargas is not alone in its use of this technique. Comparable hand stencils appear in El Castillo Cave in Spain, Chauvet Cave in southern France, and as far away as Sulawesi, Indonesia, where hand stencils have been dated to more than 40,000 BC. However, what sets Gargas apart is the unusually high number of prints showing missing or shortened fingers—a feature not commonly found in other locations.

Dating the Handprints — Aurignacian Period

The hand stencils in Gargas Cave have been attributed to the Aurignacian period, a phase of Upper Paleolithic Europe that began around 35,000 BC and ended near 25,000 BC. Radiocarbon dating from associated charcoal remains and stylistic comparisons with other cave art have placed the creation of the Gargas stencils around 27,000–25,000 BC. These dates are consistent with the early presence of anatomically modern Homo sapiens in Western Europe.

Scholars such as Jean Clottes, one of France’s leading prehistorians, have emphasized that while exact dating remains difficult without direct pigment sampling (which can be destructive), the style and subject matter of the Gargas art are clearly aligned with other verified Aurignacian works. This includes the preference for realistic animal depictions and the use of simple geometric signs alongside human forms.

Interestingly, the hand stencils are often surrounded or overlain by symbolic marks such as dots, parallel lines, and crosshatches. These signs, sometimes called tectiforms or claviforms, are found in multiple Upper Paleolithic sites and are believed to hold communicative or ritual meaning. Their presence supports the theory that the handprints were part of a broader symbolic system, possibly used to convey identity, status, or spiritual affiliation.

Count and Composition of the Handprints

To date, approximately 231 negative hand stencils have been catalogued within Gargas Cave. Among these, roughly 49 display shortened or missing fingers, primarily on the fourth and fifth digits (the ring and pinky fingers). The stencils are distributed in concentrated groups on the walls and ceilings of the central and rear chambers of the cave, suggesting that these areas were deliberately selected for communal or sacred reasons.

The colors used are primarily red ochre and black manganese, with a few rare examples in yellow ochre. This range of pigments suggests access to a variety of mineral sources, possibly gathered from riverbeds or nearby outcrops. The application technique is consistent throughout, which suggests a long-standing tradition or careful teaching of this method across generations.

The size and spacing of the hands indicate a range of participants, from small children to full-grown adults. The presence of children’s prints, in particular, suggests that Gargas Cave was not merely a site for elite rituals or adult hunting magic but may have served as a communal place of symbolic expression and teaching.

The Mystery of Missing Fingers

Mutilation Theory — Ritual or Survival?

One of the most controversial aspects of the Gargas hand stencils is the appearance of missing fingers in nearly a quarter of the examples. Some scholars in the early 20th century proposed the theory that these individuals had experienced real amputations, possibly for ritual purposes or as a form of punishment. This theory gained traction among researchers intrigued by the idea of prehistoric sacrifice or initiation rites.

However, modern anthropological studies have largely cast doubt on the amputation hypothesis. There is no skeletal evidence from Gargas or nearby sites to suggest widespread finger amputation among Upper Paleolithic populations. Moreover, the missing fingers are too consistent and limited in range to align with random accidents or trauma. Researchers such as André Leroi-Gourhan and Jean Clottes have suggested that these images more likely reflect symbolic behavior rather than physical reality.

Another plausible explanation is frostbite, which could have led to the loss of fingers in the harsh glacial environment of the Pyrenees during the Ice Age. While this remains a possibility, the consistent pattern of missing or folded fingers across multiple individuals makes it less likely to be the sole cause. No definitive conclusion has yet been reached.

Symbolism vs. Physical Reality

A more widely accepted theory today is that the missing fingers are the result of deliberate symbolic representation, rather than actual physical mutilation. This could mean that the artists intentionally folded their fingers or pressed only part of their hands against the rock before spraying pigment, in order to create a message or code. Some researchers believe that these modified handprints functioned as a proto-sign language, perhaps indicating tribal identity, spiritual beliefs, or ritual participation.

Others suggest that the hand stencils were used in numerical or calendrical systems, with each missing digit representing a count or event. Though no definitive decoding has yet been achieved, comparisons with similar hand motifs in Maltravieso Cave (Spain) and Cosquer Cave (France) show that the idea of symbolic hands was widespread.

Ultimately, the missing fingers may represent a form of spiritual or metaphysical communication, with each individual choosing how to depict their hand based on personal or group beliefs. This interpretation emphasizes the complex cognitive capabilities of Paleolithic humans and their use of abstract symbolism far earlier than once assumed.

Artistic Technique — Bent Fingers, Not Missing?

A third and increasingly supported theory is that many of the “missing” fingers are simply bent or folded, rather than absent. Experimental archaeology, including work by Jean Clottes and members of the French Prehistoric Society, has shown that curling the fingers inward before spraying pigment results in a hand stencil that appears to have missing digits.

High-resolution imaging and pigment dispersion studies confirm that the gaps between fingers often line up with natural joints, suggesting deliberate bending rather than amputation. This method would have been easy to teach and reproduce, supporting the theory of ritualized or codified gestures. In this view, the hand becomes a kind of living symbol—a human glyph meant to convey something meaningful to others in the group.

This theory also aligns with findings in other caves across Europe, where hand stencils with bent fingers appear in similar cultural contexts. It avoids the need to explain widespread mutilation and instead points to a more sophisticated symbolic culture among early Homo sapiens.

Interpretations and Cultural Context

Ritual, Identity, or Communication?

The negative handprints in Gargas Cave, especially those with missing or shortened fingers, have inspired a wide range of interpretations among archaeologists and anthropologists. Many believe the stencils played a role in ritual behavior — potentially marking rites of passage, spiritual beliefs, or group identity. The careful placement of hands, repetition of certain patterns, and clustering of prints in specific chambers suggest the act had symbolic weight far beyond decoration.

One line of theory proposes that the handprints were marks of individual identity, not unlike a personal signature. In a society without writing, such markings could indicate presence, ownership, or spiritual affiliation. Some even propose that stencils acted as part of initiation ceremonies, with young people marking their first entry into adulthood or community responsibility.

Others interpret the handprints as a form of non-verbal communication. The missing fingers could represent a kind of gesture-based code, conveying messages understood only by those within a cultural group. While this remains speculative, it’s supported by the broader trend in Upper Paleolithic art of using abstract shapes and recurring signs. These visual systems may have laid the groundwork for more complex symbolic thinking that ultimately led to writing thousands of years later.

Major Interpretations of Gargas Handprints:

- Rites of passage or initiation

- Spiritual or totemic identity markers

- Early symbolic communication

- Tribal or familial identification

- Ritual re-enactment or collective memory

Comparison with Other European Cave Art

The hand stencils of Gargas share certain features with those found in other major cave art sites across Europe, particularly in southern France and northern Spain. For example, El Castillo Cave in Cantabria, Spain, contains some of the oldest known hand stencils in Europe, with uranium-series dating placing them as early as 37,000 BC. Like Gargas, these were created using the blowing technique and appear alongside red disks and abstract marks.

In Chauvet Cave, located in the Ardèche region of France and dating to around 30,000 BC, hand stencils are also found but in smaller numbers and with less finger distortion. The focus in Chauvet tends more toward lifelike depictions of animals such as lions, rhinoceroses, and horses. Cosquer Cave, discovered in a submerged section of the Mediterranean coast, also includes hand stencils with incomplete fingers, though far fewer than Gargas. These similarities across sites point to shared traditions or symbolic systems among groups spread across vast distances during the Upper Paleolithic.

Gargas remains unique, however, in the sheer number of modified handprints and their prominent display. While similar practices appear sporadically elsewhere, no other known European cave features such a high proportion of hand stencils with missing or bent fingers. This concentration suggests a localized cultural or ritual significance that set Gargas apart from its contemporaries, even within the same general time frame.

Modern Relevance and Ongoing Debates

The art in Gargas Cave continues to challenge modern researchers, not only in terms of its technical execution but in its profound implications for our understanding of early humans. The persistence of the missing fingers mystery reflects broader uncertainties in archaeology: how to interpret material remains of a culture with no written record. It forces scholars to balance evidence with informed speculation and to develop new methods of analysis.

In recent years, advances in digital imaging and pigment analysis have opened new doors for studying sites like Gargas without damaging the artworks. 3D modeling has allowed researchers to detect subtle variations in hand position, pigment flow, and finger placement, bolstering the theory that many prints were created with bent fingers rather than physical amputations. These tools have added clarity but have not settled the central question of why these altered prints were made.

The mystery also resonates with broader questions of human expression, particularly our ancient need to leave a mark — to be remembered. The hand stencils of Gargas demonstrate not just survival, but the emergence of symbolic thinking, shared meaning, and identity, long before writing, agriculture, or modern civilization. They remind us that even in the harshest conditions, early humans sought to communicate something deeper — through image, gesture, and enduring pigment.

Key Takeaways

- Gargas Cave in France contains over 200 negative hand stencils, with nearly 50 showing shortened or missing fingers.

- These artworks date to the Aurignacian period, around 27,000–25,000 BC, and were likely created using blown pigment through bone or reed tubes.

- Theories about the missing fingers include symbolic gestures, ritual behavior, frostbite, or intentional amputation — though no definitive evidence confirms any one explanation.

- Gargas is unique among European caves for its concentration of altered hand stencils, suggesting local cultural or spiritual significance.

- Ongoing research using modern imaging and archaeology continues to explore the meaning behind these enigmatic marks.

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes Gargas Cave unique compared to other cave art sites?

Gargas has the largest number of negative hand stencils with modified fingers in Europe, a phenomenon not seen in such concentration anywhere else.

Are the missing fingers in the handprints due to real amputations?

There is no skeletal or archaeological evidence of widespread amputation; most scholars now believe the missing fingers were symbolic or due to bent fingers.

When were the handprints in Gargas Cave created?

They were likely made during the Aurignacian period, approximately 27,000 to 25,000 BC, by early Homo sapiens in Ice Age Europe.

What materials were used to create the stencils?

Artists used mineral pigments like red ochre and black manganese, applied by blowing pigment around a hand pressed against the cave wall.

Can the public visit Gargas Cave today?

Yes, but access is limited and controlled to preserve the fragile artwork. Guided tours are available, focusing on conservation and interpretation.