Carnival freak shows first took hold in the 18th century and gained explosive popularity throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. These exhibitions featured individuals with unusual physical conditions or abilities, presented as entertainment under circus tents, traveling shows, and dime museums. Audiences flocked to see so-called “human oddities” with a mix of shock and fascination. For many Victorians, the freak show offered a rare window into what was perceived as both the grotesque and the marvelous.

The appeal of the sideshow wasn’t just about the people on display, but also what they represented. To audiences, freaks symbolized mystery, abnormality, and the edge of scientific understanding during a time when medicine and biology were still poorly understood. At the same time, attending a freak show let viewers feel both morally superior and morbidly entertained. These shows became not just social events but moments of voyeurism wrapped in pageantry.

Curiosity or Cruelty? The Psychology Behind the Spectacle

Freak shows operated at the intersection of art, science, and exploitation. Performers were often framed as “living art exhibits,” with banners, posters, and dramatic introductions turning them into mythical figures. The careful staging of their appearances — from lighting to costume — turned their physical traits into something close to a theatrical tableau. What was seen as monstrous or divine was stylized in such a way that the body itself became art.

Psychologists and historians alike have explored the deeper impulses behind society’s fascination with these performers. Some argue it was fear of the unknown; others say it was a twisted form of admiration. Regardless, these shows fed on public discomfort and fascination, often reinforcing cultural and moral boundaries rather than breaking them. Art played a role in shaping those reactions, offering both a visual record and a form of propaganda.

The Artists Behind the Curtains: Painters, Photographers, and Promoters

The spectacle of freak shows was fueled not only by the performers but also by the artists and promoters who packaged them for mass appeal. In the 19th century, vibrant lithographs and carnival posters transformed real people into fantastical creatures, often with exaggerated claims like “The Mule-Faced Woman” or “The Elastic-Skinned Man.” These illustrations were key to attracting audiences and selling the myth before anyone stepped foot inside a tent. The artistic style was loud, colorful, and intentionally over-the-top.

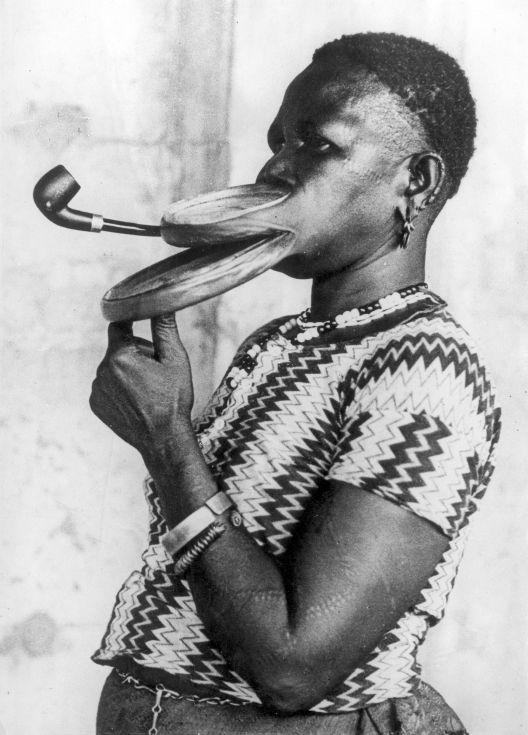

Photography also played a pivotal role in documenting and marketing sideshow performers. From the 1860s onward, carte de visite photographs and cabinet cards featured “freaks” posed in a dignified or dramatic fashion, giving them both commercial and personal value. These images were sold as souvenirs or collectibles, much like baseball cards. In many cases, performers would even earn income from selling these portraits to their fans.

Eccentricity on Canvas and Film

One of the most influential 20th-century artists to document sideshow subjects was Diane Arbus. In the 1960s, Arbus photographed individuals living on the margins of society — dwarfs, giants, transgender people, and circus performers. Her portraits emphasized humanity over spectacle, capturing vulnerability and pride in equal measure. These images challenged the viewer to see past the surface and question their own discomfort.

Long before Arbus, photographers in the 19th century were creating haunting portraits of performers like the bearded lady Annie Jones or the conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker. These images were not merely promotional tools; they became part of the visual culture surrounding physical difference. By the early 20th century, freak show aesthetics had even crept into cinema, most notably in Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks, which cast real-life sideshow performers in leading roles. The line between art and exploitation blurred.

The P.T. Barnum Effect: Art of Deception and Display

No figure looms larger in the history of freak shows than Phineas Taylor Barnum. Born in 1810 in Bethel, Connecticut, Barnum revolutionized American entertainment through spectacle and marketing. He acquired his first “freak” performer, Joice Heth, in 1835, claiming she was the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington — a complete fabrication. Barnum’s genius lay in his understanding that people would pay to be fooled, so long as it was entertaining.

In 1841, Barnum purchased Scudder’s American Museum in New York City and transformed it into a hub of curiosities, oddities, and live performances. Among his most famous acts was General Tom Thumb, a man named Charles Stratton who began performing at age five and stood just over three feet tall. Barnum crafted elaborate backstories, designed ornate posters, and staged dramatic appearances that captivated the public. Art and illusion became his tools of control.

Creating Legends Through Visual Illusion

Barnum understood the power of visual storytelling better than most. He employed artists to create fantastical banners and illustrations that exaggerated or completely fabricated traits of his performers. For example, “The Fiji Mermaid” was a grotesque taxidermy hoax combining a monkey’s torso and a fish’s tail, passed off as real through dramatic display techniques. His museum became not just a place of entertainment, but a theatrical canvas.

The use of staging, lighting, and costuming elevated the performance into a form of visual art. Performers were often costumed in ways that emphasized their physical uniqueness — albinos dressed as angels, dwarfs in military garb, or giants in elegant suits. These decisions were not made by accident but were part of a carefully curated aesthetic designed to sell tickets and stir emotion. Through deception and design, Barnum turned spectacle into show business.

Bodies as Spectacle: The “Art” of Othering in Victorian Society

Freak shows didn’t just play with biology — they weaponized it. During the 19th century, performers from non-Western backgrounds were presented in freak shows not only as physical oddities but as racialized spectacles. The colonial gaze portrayed them as primitive, uncivilized, or even subhuman. This was a time when imperialism and pseudoscience walked hand-in-hand, and freak shows became visual platforms for both.

One of the most infamous examples was Saartjie Baartman, known as the “Hottentot Venus,” who was exhibited in London and Paris in the early 1800s. Her body, particularly her large buttocks, was dissected in paintings, sketches, and live performances, all under the pretense of scientific inquiry. She died in 1815, and her remains were displayed in France for over a century. Her story reflects how freak shows functioned as artistic and political weapons.

Grotesque Beauty or Institutional Violence?

Victorian art and literature often reflected the same attitudes found in freak shows. Scientific illustrations would depict the skull shapes of so-called “degenerate races” next to Europeans, reinforcing ideas of racial superiority. Artists who participated in or documented sideshow life contributed — knowingly or not — to these dehumanizing narratives. Yet some subverted these ideas by portraying their subjects with dignity and realism.

While some illustrators romanticized these performers as noble savages or angelic monsters, others challenged prevailing notions. A few medical illustrators in the 1880s and 1890s began to focus on anatomy without judgment, offering more neutral — if clinical — representations. Over time, these depictions helped shift artistic treatment from grotesque to humanized. Still, the Victorian lens remained largely one of othering, making the freak show both an artistic curiosity and a moral stain.

Icons of the Sideshow: Real Lives Behind the Canvas

Behind every act was a real person — often intelligent, witty, and painfully aware of how they were seen. Chang and Eng Bunker, born in 1811 in Siam (now Thailand), became the original “Siamese Twins.” They toured extensively in the United States, eventually marrying sisters Adelaide and Sarah Yates in 1843 and fathering 21 children between them. Despite their fame, they struggled with medical issues and the psychological toll of being a permanent exhibit.

Another tragic figure was Julia Pastrana, born in 1834 in Mexico. Covered in thick black hair and suffering from a genetic disorder that distorted her face and gums, she was exhibited across Europe as “The Ape Woman.” Married to her manager Theodore Lent in the 1850s, she died in 1860 shortly after childbirth. Shockingly, her mummified body continued to be displayed until the 1970s. Only in 2013 was she finally buried in Mexico.

Agency or Exploitation? When Performers Took Control

While many freak show performers were exploited, some fought for their rights and profits. Tom Thumb (Charles Stratton) accumulated wealth, married Lavinia Warren in a highly publicized ceremony in 1863, and lived a relatively comfortable life until his death in 1883. He and Lavinia often negotiated their contracts and were shrewd in marketing their image. Some performers formed their own troupes, reclaiming the right to self-presentation.

Others challenged the norms by writing autobiographies or seeking legal control over their own publicity. Chang and Eng owned land and slaves in North Carolina before the Civil War, complicating their historical legacy. Julia Pastrana, despite being manipulated by her husband, reportedly sought love and family rather than fame. Their stories remind us that even those marketed as curiosities had agency — though often limited — and aspirations beyond the stage.

Freak Shows and Modern Art: From Diane Arbus to the Avant-Garde

The decline of freak shows in the mid-20th century coincided with a shift in cultural values and the rise of civil rights movements. Yet their imagery lived on in the work of modern artists who revisited the freak show’s aesthetic and ethical questions. Diane Arbus, who photographed circus performers and mentally disabled individuals in the 1960s, brought a stark intimacy to her subjects. Her photos suggested that what made someone a “freak” was often more about perception than biology.

Surrealists like Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst also borrowed freely from sideshow motifs. Dalí, in particular, incorporated themes of physical distortion, mutation, and theatricality into his paintings. These images echoed the visual language of carnival art — exaggerated bodies, shock, and symbolic deformity. The freak show offered modern artists a way to critique conformity, normalcy, and aesthetic ideals.

Sideshow Symbols in Popular Culture and Design

Freak show aesthetics still shape many areas of visual culture today. Tattoo artists often draw inspiration from vintage sideshow posters, and fashion photographers like Tim Walker have staged photoshoots resembling circus tents. Films like The Elephant Man (1980) and Big Fish (2003) resurrected themes of misunderstood oddities and romanticized misfits. This imagery has also influenced everything from album covers to graphic novels.

Pop surrealist painters like Mark Ryden and Marion Peck continue to explore these themes, blending innocence with grotesquerie. In doing so, they keep the freak show alive — but with new meaning. Today’s artists often seek to humanize or deconstruct the spectacle, rather than exploit it. The freak show’s visual DNA is embedded in the broader culture, from gallery walls to Hollywood backlots.

The Legacy of Spectacle: Ethics, Memory, and the Artistic Archive

While freak shows have disappeared from mainstream entertainment, their legacy endures in museums, archives, and academic debate. Institutions now face the difficult question of whether to preserve, display, or hide these artifacts. Some museums, like the Wellcome Collection in London, have reevaluated the way they present anatomical and medical oddities. Others, like the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, continue to showcase such material while addressing its troubling past.

The ethics of exhibiting human difference remain unresolved. Should sideshow memorabilia be celebrated as art, or buried as exploitation? Some curators argue that erasing these histories denies the reality of the people involved, while others believe continued display perpetuates harm. Artistic works that depict freak show figures now often include historical context or critical commentary to avoid glamorizing suffering.

Collecting the Grotesque: Who Owns the Image of the Freak?

Freak show posters, photographs, and even body parts have become collectors’ items, raising thorny legal and ethical issues. Ownership often falls to private collectors, with little regulation on how these items are presented. Digital archives have complicated matters further, with thousands of images shared online, sometimes without credit or consent. Who gets to tell these stories — and how — is still being contested.

Some descendants of performers have spoken out about the misuse of their relatives’ images. The remains of Julia Pastrana, for instance, were fought over for decades before her burial. This tension between exploitation and preservation haunts every gallery and archive that handles such material. Artists and historians must tread carefully, recognizing that these aren’t just relics — they’re real lives, shaped by spectacle and recorded in art.

Key Takeaways

- Freak shows combined art, marketing, and exploitation to create a powerful form of public spectacle.

- Artists and photographers shaped the freak show’s legacy through posters, portraits, and film.

- Performers like Chang and Eng Bunker and Julia Pastrana lived complex lives behind their stage personas.

- Diane Arbus and surrealist painters reinterpreted sideshow aesthetics in modern art.

- Ethical debates continue around the preservation and display of freak show artifacts.

FAQs

- When did carnival freak shows begin?

Freak shows began in the 18th century and became widely popular by the 19th century. - Who was the most famous freak show promoter?

P.T. Barnum is the most iconic figure in freak show history, known for turning it into big business. - Did freak show performers have control over their careers?

Some, like Tom Thumb, negotiated contracts and built wealth, though many were exploited. - Are freak shows still legal today?

Most countries banned them by the late 20th century due to concerns over human rights and dignity. - How has modern art dealt with freak show imagery?

Artists like Diane Arbus and Salvador Dalí explored these themes to critique society’s view of difference.