In the shifting world of the Belle Époque and early 20th-century Europe, where new artistic movements flourished and old traditions were challenged, a select few women stood not on stage or canvas, but just behind it — influencing, encouraging, and directing. Misia Godebska, born in 1872 and later known as Misia Sert, was one of those rare figures whose presence shaped the direction of European art, music, and design. Though she was not an artist in the traditional sense, her influence was both subtle and lasting, guiding some of the greatest talents of her generation. She was not merely a muse in the passive sense but an active force in bringing artistic visions to life.

Misia’s life was rich in culture, intellect, and artistic companionship. She was close to painters like Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, composers like Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, and innovators like Sergei Diaghilev and Coco Chanel. Her salons were places where ideas were exchanged with civility and taste, far removed from the radicalism and upheaval that would later redefine modernism. What set her apart from other socialites of her time was not wealth or scandal, but the consistency of her support for great art — often quietly and without seeking personal gain. Her influence crossed artistic disciplines and endured over decades, even as France and Europe underwent dramatic changes.

To understand the influence of Misia Godebska is to understand the human side of the artistic revolutions that swept through Europe between 1890 and 1930. She was born into a cultured household, educated to the highest standards, and deeply connected to the core of French and European creativity. In her story, we do not find political posturing or fashionable rebellion, but refined taste, loyal patronage, and a steady devotion to excellence. Through her long life, which ended in 1950, Misia remained a beacon of traditional European culture amid a world that often seemed determined to discard it.

Misia’s legacy is best viewed through the company she kept and the artists she inspired. Some were her close companions; others encountered her only briefly, yet left lasting works shaped by her presence. This article will explore not only her deep influence on Vuillard — the painter with whom she is most associated — but also her impact on composers, dancers, and writers. We will examine her upbringing, relationships, and the world she cultivated, always remembering that behind the canvas and beyond the stage, there was often Misia.

Her Upbringing and Entry into the Arts

Misia Godebska was born on March 30, 1872, in Saint Petersburg, Russia, into a family steeped in classical European culture. Her father, Cyprian Godebski, was a respected Polish sculptor whose works can still be found in several European capitals. After her mother’s early death, Misia was raised in Brussels by her paternal grandfather, and later spent formative years in Paris. This early blend of Russian, Polish, and French influences helped develop in her a cosmopolitan sensibility — traditional yet deeply cultured, fluent in both language and music.

Her formal education was rooted in the arts, and from an early age, Misia displayed considerable musical talent. She studied piano at the Conservatoire de Paris, where her instructors included Gabriel Fauré and Camille Saint-Saëns, two towering figures of French music. By her teenage years, she had already performed in public, gaining praise for her discipline and refined touch — not just for her technique, but for her musical understanding. While Misia never pursued a full career as a concert pianist, the skills she developed would become a vital part of her artistic identity and social role.

Roots in Tradition and Culture

In 1893, at the age of 21, Misia married Thadée Natanson, the co-founder and editor of La Revue blanche, a major literary and artistic journal in Paris. This marriage brought her directly into the heart of Paris’s avant-garde circles. Through the Natansons, she met and hosted many of the era’s rising talents — not just painters and writers, but composers, dancers, and designers. The Natanson home became a cultural center, and Misia’s influence on the magazine’s artistic direction was significant, even if not always publicly acknowledged.

It was during these years that Misia first took on the role that would define her life — not as a performer, but as a supporter of serious art and a discerning voice in cultural conversations. She had no patience for pretense and avoided flamboyant politics, preferring instead to foster environments where quality and excellence could flourish. Misia was not interested in passing trends. She was interested in beauty, balance, and the timeless values of great art.

Vuillard and the Beauty of Quiet Observation

Of all the artists whose lives intersected with Misia’s, none was more deeply influenced by her than Édouard Vuillard. Born in 1868, Vuillard was part of the Nabis, a group of post-Impressionist painters dedicated to exploring the spiritual and symbolic aspects of domestic life. Vuillard met Misia during the 1890s, and their association lasted through the most important phase of his artistic career. He was a frequent guest in her home and accompanied her and Thadée Natanson on vacations, capturing scenes of their elegant yet intimate social life in his paintings.

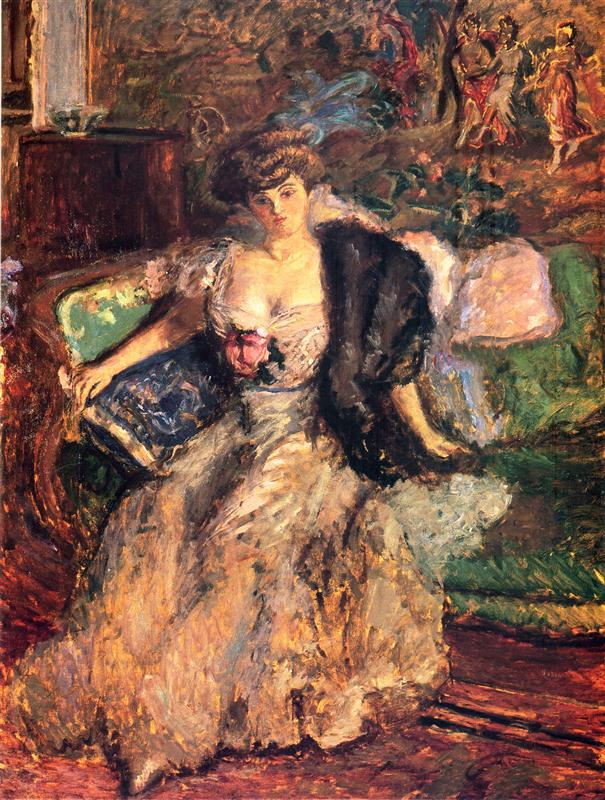

Vuillard was fascinated by domestic interiors, and Misia provided him with the perfect setting — refined rooms filled with music, conversation, and quiet charm. In works like The Sitting Room (1897) and Misia at the Piano, she appears not just as a subject, but as a central element in the composition’s atmosphere. She was not posed or theatrical; she was observed — gracefully, naturally, and always with a sense of presence that anchored Vuillard’s vision. His brush captured not just her appearance but the ambiance of her world.

The Muse Behind the Domestic Interior

While Vuillard never declared romantic feelings for Misia, scholars and biographers have long noted the depth of his emotional attachment to her. Some suggest that he may have harbored unspoken affection, but there is no evidence of any impropriety or relationship beyond friendship. What is undeniable, however, is that Misia was essential to Vuillard’s development as a painter of interiors. She offered him not only access to refined domestic spaces but also a human subject who embodied the qualities he most valued — intelligence, elegance, and emotional restraint.

Their relationship remained close even after her marriage to Natanson ended in 1905. Vuillard continued to paint her, and they remained in each other’s orbit for decades. Unlike the fleeting relationships that often marked the Parisian art scene, Vuillard’s bond with Misia was steady, respectful, and rooted in shared aesthetic values. She gave him a world to observe, and he gave that world form and color, with her at its center. This quiet collaboration stands as one of the most fruitful in French art history.

Other Artists Who Found Inspiration in Her Circle

Misia’s influence extended far beyond her bond with Vuillard. She also inspired, supported, and collaborated with several other major figures in painting, music, and ballet. Among these was Pierre Bonnard, a fellow Nabis painter who, like Vuillard, was fascinated by domestic life and interior scenes. Bonnard painted Misia in group settings, capturing the refined elegance of her world. His works, while more decorative than Vuillard’s, also testify to the central role Misia played in shaping artistic taste around the turn of the century.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, another frequent guest in the Natanson circle, produced several lithographs of Misia for La Revue blanche. These works portray her as stylish, confident, and fully integrated into the cultural elite of the time. Auguste Renoir, whose career was already well established by the early 1900s, painted a portrait of Misia in 1904. Though their relationship was not especially close, his willingness to paint her confirms her status as a woman of distinction and cultural importance in the Paris art world.

Bonnard, Lautrec, Renoir, and More

In the world of music, Misia’s friendships and patronage proved equally influential. She was a devoted supporter of Claude Debussy, whose innovative compositions were often misunderstood in their time. Misia not only encouraged Debussy but also promoted performances of his work among her social circle. Later, she became a close associate of Sergei Diaghilev, the Russian impresario behind the Ballets Russes, which revolutionized dance in the early 20th century. Misia provided critical financial support to Diaghilev on several occasions, helping him stage productions that would otherwise have been impossible.

There is also Maurice Ravel, whose opera L’enfant et les sortilèges contains characters that some biographers have speculated were inspired by Misia’s personality. While this connection is unconfirmed, it reflects the strong impression she left on those around her. She was also a longtime friend of Jean Cocteau, whose writings and artistic productions often intersected with the creative circles she helped cultivate. Finally, Misia introduced Coco Chanel to Diaghilev and others in the arts, helping Chanel form the connections that would eventually lead her to collaborate on ballets and stage designs.

The Paris Salon as a Place of Taste and Judgment

Misia’s influence was most visible in her salons — private, cultured gatherings that brought together the leading minds of art, literature, and music. Unlike today’s media-driven cultural spaces, these salons operated on subtlety and seriousness. They were not noisy or political but marked by refined discussion, musical performance, and artistic exchange. In Misia’s drawing rooms, artists came not to posture or argue but to be heard, respected, and challenged on the basis of their work and their talent.

Her salons were carefully curated environments that mirrored Misia’s aesthetic values: taste, order, and restraint. Guests included composers like Ravel and Debussy, painters like Vuillard and Bonnard, and writers such as Colette. The atmosphere was elegant but never showy. Misia did not seek attention or acclaim for herself — instead, she was known for her ability to listen, to judge fairly, and to offer both criticism and encouragement without vanity or sentimentality.

A Quiet Power Behind the Curtain

Misia’s gatherings served as proving grounds for ideas, performances, and collaborations. More than once, works of music or literature debuted informally in her home before ever reaching the public stage. In this way, her influence operated behind the scenes — guiding what was seen, read, and heard in more formal venues. It was her private opinion, not public declarations, that helped shape artistic careers.

Her salons stood apart from the increasingly politicized or experimental gatherings found elsewhere in Europe at the time. While others embraced chaos or ideological rebellion, Misia stood for continuity, balance, and tradition. Her aesthetic ideals were rooted in centuries of European culture. She was not a revolutionary, but a steward — preserving and transmitting classical values in a time of great change.

A Life Lived in Loyalty to the Arts

Misia’s loyalty was one of her defining virtues. Unlike many in her circle who drifted in and out of friendships based on fashion or fame, she remained steadfast to those she believed in. Her commitment to Sergei Diaghilev is a striking example. Even as the Ballets Russes faced financial ruin, Misia stepped in with practical help — not out of sentiment, but because she believed in the work. She understood that genius often came with disarray, and she was willing to provide the support that others would not.

Her friendships with artists like Debussy, Chanel, and Cocteau also stood the test of time. She was not impressed by celebrity, but by sincerity and talent. Over decades, she maintained a consistent presence in the lives of those she had once encouraged. When relationships ended, as they sometimes did, it was usually because others moved on — not because Misia withdrew. Her commitment to her friends and their work gave her a kind of moral authority in the arts community that few could match.

Friendship, Patronage, and Personal Strength

Misia’s marriages brought her into public view, but they never defined her. Her first husband, Thadée Natanson, introduced her to the world of publishing and the avant-garde. Her second, Alfred Edwards, was a newspaper magnate. Her third and most dramatic marriage was to painter José-Maria Sert, whose affairs and personal excesses were notorious. Still, Misia remained composed. Even as her personal life grew complex, she continued to support the arts with grace and dignity.

Her Catholic upbringing and Polish nobility gave her a strong foundation. Misia rarely spoke about politics or religion in public, but those close to her recognized the deep moral seriousness beneath her charm. She disapproved of vulgarity, was suspicious of modernist ideology, and valued discretion. In a world increasingly drawn to spectacle and self-promotion, Misia was a quiet force of judgment and endurance — loyal to the arts, and to the people she believed in.

Her Enduring Legacy as a Patron and Muse

Misia’s impact on European art did not come from producing work herself, but from making great work possible. Her taste, funding, and influence helped bring to life major artistic achievements — not once, but over and over again. Without her quiet direction and practical support, some of the most famous works of music, painting, and ballet might never have reached the public. She was not a name on a canvas, but a trusted presence behind it — a woman who enabled creativity in others.

Her contribution to Édouard Vuillard’s career alone would have secured her a place in art history. But when viewed alongside her support of Debussy, Diaghilev, and Chanel, her role becomes even more significant. While other muses inspired one man, or one movement, Misia’s influence crossed genres and generations. She inspired images, performances, and compositions — and also provided the resources and environments where those works could be developed with care.

A Woman of Taste in an Age of Change

Misia’s legacy has sometimes been obscured by the legends that surround her. She has been romanticized, fictionalized, and misunderstood. But the real Misia — the woman who judged performances with a clear eye, who paid artists’ debts without fanfare, who hosted salons not for show but for sincere dialogue — is a far more impressive figure than the myth. She did not seek to challenge the world, but to preserve its highest expressions.

As the 20th century progressed and traditional artistic values were increasingly questioned, Misia remained committed to excellence. She disliked loud ideologies and distrusted novelty for novelty’s sake. She was, in many ways, a holdover from a more ordered world — one that valued grace, discipline, and substance. In our own era, filled with noise and distraction, Misia’s example remains a timely reminder: true influence does not come from self-promotion or spectacle, but from quiet authority, loyalty, and the love of great art.

Key Takeaways

- Misia Godebska was born in 1872 and raised in a cultured, European household rooted in the arts.

- She inspired and supported major artists such as Vuillard, Debussy, Diaghilev, and Chanel.

- Her influence was defined by refined taste, loyalty, and support for lasting artistic values.

- Misia’s salons shaped the Parisian cultural landscape from the 1890s to the 1930s.

- Her legacy reminds us of the enduring power of quiet, principled cultural stewardship.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Was Misia Godebska an artist herself?

No, but she was a trained pianist and deeply involved in the arts as a patron and muse. - Did Misia and Vuillard have a romantic relationship?

There is no confirmed romance; their relationship was emotionally close but respectful. - What was her role in the Ballets Russes?

Misia provided critical financial and moral support to Sergei Diaghilev and his productions. - Did she influence composers like Debussy and Ravel?

Yes, she was close to Debussy and speculated to have inspired aspects of Ravel’s opera. - Why is she important today?

Misia exemplifies the enduring value of traditional cultural patronage and loyal artistic support.