In the postwar decades, Hashima Island—known in Japan as Gunkanjima or “Battleship Island”—caught the attention of local painters drawn to its dense industrial silhouette and stark isolation. As early as the 1950s, Japanese artists began to depict the island as a symbol of the nation’s modern transformation. Yamashita Kiyoshi, a self-taught artist famous for his detailed paper collage landscapes, captured industrial scenes reminiscent of Hashima’s cityscape. His work reflected not just architectural interest but a deeper narrative of Japan’s economic rise through coal-powered industrialization.

By the 1960s, oil painters in Nagasaki Prefecture were regularly incorporating Hashima’s image into their visual storytelling. The stacked apartment buildings, steel walkways, and towering smokestacks were frequently painted with dramatic contrasts—gray concrete against stormy skies or glinting sun. The mood of these works often shifted between admiration for Japan’s post-Meiji engineering prowess and a quiet acknowledgment of the human lives enclosed within its walls. These early artistic portrayals laid the foundation for a long-lasting visual fascination with Hashima as both monument and memory.

Photographic Realism and the Haikyo Aesthetic

With the decline of coal mining and the complete evacuation of the island by April 20, 1974, Hashima became a silent relic. By the 1990s, a new generation of artists emerged—not with brushes, but cameras. These photographers pioneered a genre known as haikyo, or ruin photography. Chief among them was Yūji Saiga, whose photo collections in the late 1990s and early 2000s became iconic representations of Gunkanjima’s decay. His book Gunkanjima—Record of a Ruined Island captured rooms frozen in time, with schoolbooks still on desks and rusted machinery standing like grave markers.

Saiga’s photographs went beyond documentation. He framed Hashima’s abandonment with an aesthetic that emphasized entropy, silence, and the eerie beauty of stillness. Through long exposure and high-contrast black-and-white images, he allowed decay to speak visually, creating a solemn dialogue between industry and impermanence. Haikyo photography grew rapidly in popularity in Japan, and soon became an artistic movement on its own, inspiring books, gallery exhibitions, and even film set designs.

Global Artists’ Fascination with Urban Decay

By the early 2000s, foreign photographers and artists began traveling to Hashima, drawn by its unique juxtaposition of nature’s reclamation and man-made geometry. While most did not step foot on the island until public tours began in 2009, many studied it through aerial imagery and earlier Japanese works. Their interpretations often placed Hashima within a larger Western tradition of the sublime ruin—connecting it to European depictions of abandoned castles, Roman ruins, or even postwar European industrial sites.

Artists from Germany, Britain, and the United States, some influenced by Brutalist architecture, treated Hashima as a living sculpture. The repetitive, monolithic structures and modular concrete blocks were likened to Brutalist city plans of the 1950s and 1960s. In photo exhibitions in Berlin and London during the mid-2000s, Gunkanjima’s stark visuals were often presented alongside decommissioned European coal plants and wartime bunkers. The result was a visual language of decay that transcended borders, portraying the end of an industrial age with somber reverence.

Iconic Early Artworks and Exhibitions Featuring Hashima:

- Yamashita Kiyoshi’s oil series (1960s)

- Yūji Saiga’s photo-essay collections (Gunkanjima, 1997–2004)

- Urban Exploration exhibitions in Berlin’s Haubrok Galerie (2006) and London’s Tate Modern “Ghost Machines” show (2008)

Industrial Memory and Wartime Legacy in Artistic Themes

Depictions of Industrial Might

During its peak years between 1916 and 1941, Hashima Island became a visual embodiment of Japan’s industrial might. Owned by Mitsubishi since 1890, the island was rapidly developed into a coal-mining powerhouse. Artists from the Taisho (1912–1926) and early Showa (1926–1989) periods celebrated this transformation. Posters, ink drawings, and murals commissioned by Mitsubishi or local trade unions depicted heroic miners, vast conveyor belts, and multi-story dormitories. These works emphasized the theme of modernity—human control over nature, and industrial expansion as a national virtue.

In particular, art produced during the 1930s reflected Japan’s push for industrial self-sufficiency. As the country moved toward wartime production, Hashima became a visual metaphor for endurance and strength. Some artists portrayed it in almost utopian terms: a self-contained island of innovation, with schools, cinemas, and stores all suspended above the open sea. These images often lacked the human cost behind such productivity, focusing instead on the grandeur of steel and stone.

Artists Confronting Forced Labor Histories

Not all artistic portrayals of Hashima are celebratory. During World War II, from 1939 to 1945, the island became a forced labor site for thousands of conscripted Korean and Chinese workers. Many of these individuals were compelled to work under extreme conditions, with limited safety, poor nutrition, and no freedom to leave. After the war, these abuses were widely documented, though not often depicted in Japanese postwar art. However, contemporary Korean and Chinese artists have used their work to confront this painful legacy.

Shin Hak-chul, a Korean painter born in 1940, created powerful mixed media installations in the 1990s addressing the colonial suffering endured by Korean workers on Japanese soil. One of his pieces included rusted iron plates engraved with names of deceased miners, set beside original Mitsubishi blueprints of Hashima. Another artist, Li Jin from Beijing, created abstract charcoal and ash-on-paper compositions resembling collapsed tunnels and suffocated spaces, evoking the claustrophobia and dehumanization felt by forced laborers. These artworks do not shy away from the harsh truths and often serve as historical correctives to earlier, sanitized depictions.

Silence vs. Witness: Competing Artistic Narratives

A significant artistic tension lies between silence and witness—how to represent a place so charged with history, without distorting it. Japanese artists have at times opted for restraint, choosing silence as a thematic device. Sparse ink paintings, minimalist installations, or carefully chosen still photographs suggest loss without explicitly naming it. This can be seen in works by Tadanori Yamaguchi, whose 2005 series Coal Ghosts captured Hashima’s interiors with intentional underexposure, leaving much in shadow.

By contrast, foreign artists—especially those from Korea and China—tend to take a more declarative approach. Their works often carry direct visual references to suffering, including barbed wire, shackled figures, or archived testimonies. Western artists, too, vary in approach. Some avoid moral commentary, focusing purely on aesthetic decay, while others incorporate documentary elements—interviews, sound clips, or declassified documents—to balance beauty with historical witness. The divergence in tone reflects deeper cultural differences in confronting memory, apology, and accountability.

Hashima in Cinema, Architecture, and Popular Visual Arts

From Bond Villains to Battles: Movie Portrayals

Hashima Island has appeared prominently in global cinema, most famously as the visual inspiration for the villain’s lair in the 2012 James Bond film Skyfall. Although filming did not occur on the island itself, set designers explicitly modeled the abandoned stronghold after Gunkanjima’s dense, decaying architecture. The film’s cinematographer, Roger Deakins, studied photographs by Yūji Saiga and other haikyo artists to replicate the textures and eerie silence of the island. The result was a cinematic environment that felt both exotic and desolate—a fitting hideout for a cyber-terrorist with a vendetta.

Japanese cinema has also made use of Hashima’s haunting presence. Battle Royale II: Requiem (2003) featured scenes filmed on the island, leveraging its stark corridors and collapsed classrooms to reinforce the film’s dystopian tone. Even more direct was the 2009 Japanese thriller Hashima Project, a horror film explicitly set on the island and based on urban legend. These cinematic interpretations often mirror artistic motifs—emptiness, tension between past and present, and the juxtaposition of death and beauty.

Manga and Anime as Artistic Mediums

In Japanese manga and anime, Hashima has inspired countless dystopian and post-apocalyptic worlds. The towering vertical buildings and isolation from the mainland make it a natural symbol for containment and despair. In Attack on Titan, artist Hajime Isayama stated that the walled city concept was influenced in part by Hashima’s enclosed architecture. Similarly, the island appears in One Piece, where the “Enies Lobby” setting mimics the sea-bound isolation and militarized layout of Gunkanjima.

Tsutomu Nihei, known for his manga series Blame! and Knights of Sidonia, draws heavily on Hashima’s architectural density. His backgrounds feature vertical shafts, maze-like corridors, and cavernous spaces reminiscent of coal shafts and apartment complexes. In his 1995 sketchbook, Nihei acknowledged Hashima as a model of man-made labyrinths. The link between manga and real-world ruins has deepened in recent years, with fans visiting the island on official tours, camera in hand, retracing the paths of their favorite characters.

Architectural Drawings and Reimaginings

Even in academic settings, Hashima has become a favorite subject of architectural reinterpretation. Since the island was reopened for limited public access in 2009, students from institutions like Tokyo University and Waseda University have used it as a case study in adaptive reuse, memorial design, and spatial entropy. Concept drawings often imagine what the island might become: a peace park, a monument, or even a vertical urban farm. These speculative renderings are artistic in nature, blending real historical structures with futuristic visions.

Virtual reconstructions of Hashima also exist as a form of digital art. One example is the 2013 project by 3D modeling artist Masaki Fujihata, who used drone footage and laser scanning to recreate the island in an immersive installation. His work, shown at the ICC Gallery in Tokyo, allowed viewers to “walk” through the island in VR. These pieces blend artistry, technology, and architecture, offering new ways to engage with a site that is physically dangerous but visually compelling.

Ruins as Beauty: Philosophical and Aesthetic Reflections

Wabi-Sabi and the Japanese Eye

In traditional Japanese aesthetics, the concept of wabi-sabi—the beauty found in imperfection and impermanence—offers a natural framework for interpreting Hashima through art. Artists working within this tradition embrace the island’s decay not as loss, but as transition. Crumbling walls, weathered doors, and moss-covered stairs become testaments to time, not failures of maintenance. Ink painters such as Koji Yamagata have captured these textures in monochrome, using brushstrokes that mirror the rough grain of concrete or the soft bloom of sea salt on rusted rebar.

Poets, too, have turned to Hashima. Short-form haiku have emerged in local journals and exhibitions, framing the island’s stillness with seasonal imagery. One such poem by Hiroshi Ito reads: “Empty mine tunnels / wind from sea to memory— / gulls circle silence.” Such works place Hashima within Japan’s long tradition of finding dignity in decay, even when the past holds pain. The goal is not erasure, but quiet recognition.

Romanticizing Abandonment: A Western Lens

Western artists and photographers often romanticize ruins in a different way—focusing on the sublime, the dramatic, and the uncanny. This tradition dates back to the 18th-century fascination with ancient Roman ruins and Gothic architecture. Gunkanjima fits this aesthetic mold almost too perfectly. Its Brutalist concrete forms, positioned amid turbulent sea, evoke feelings of awe and melancholia. This visual power has made it a popular subject in European and American photography books on “beauty in decay.”

There is, however, criticism of this approach. Some argue that romanticizing Hashima’s abandonment risks ignoring the island’s full history. When the focus is purely on textures and compositions, the human experiences behind the structures can be lost. Nonetheless, the visual tradition persists. Artists like Roman Loranc, Edward Burtynsky, and others have captured the island’s decay with meticulous composition and rich black-and-white tonality, adding to a global dialogue on the aesthetics of abandonment.

Memory, Space, and Ghosts in Modern Art

Hashima Island’s powerful presence has also inspired installation and conceptual artists who work with memory and absence. These works are often immersive, involving sound, light, and tactile materials that simulate presence through void. In 2011, Japanese artist Miwa Yanagi created a multi-room installation called Hashima: Room of Echoes, using archival recordings, crumbled coal, and projected images to recreate the sensory feeling of the island. Visitors walked across real gravel from the site while listening to former residents speak about their lives.

Other artists have explored the “ghost” of Hashima—how a place can haunt collective memory long after being vacated. Digital artist Chiharu Shiota included elements of Hashima’s spatial layout in her string installations, where red thread connected hundreds of keys suspended in air—each representing a lost apartment or family. These works use metaphor to link the physical island to broader themes of loss, memory, and the fragility of human endeavor.

Recurring Visual or Symbolic Themes in Hashima-Inspired Art:

- Rusted metal and weathered concrete

- Cracked windows and broken walkways

- Fog, water, and silence as metaphors

- Juxtaposition of manmade vs. nature reclaiming

- Emptiness as echo of human passage

Key Takeaways

- Hashima Island, or Gunkanjima, has inspired generations of artists across Japan and the world, ranging from traditional painters to contemporary installation creators.

- Its unique industrial architecture and history of abandonment make it a compelling symbol of modern decay, industrial glory, and national transformation.

- Artists have engaged with both the beauty and the trauma of the island, particularly regarding its role in wartime forced labor under Japanese control during World War II.

- Western and Eastern aesthetics approach Hashima differently: where Japanese artists often embrace wabi-sabi and silence, Western interpretations tend to emphasize dramatic ruin and grandeur.

- Hashima’s influence extends into film, manga, and digital art, making it not only a physical site but a lasting symbol in popular and visual culture.

FAQs

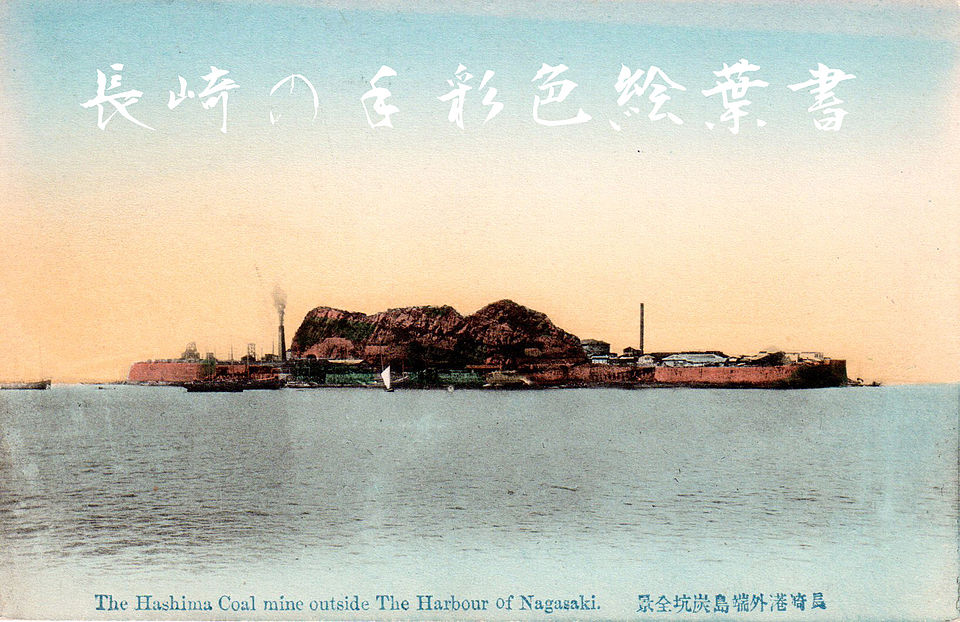

What is Hashima Island and why is it called “Battleship Island”?

Hashima Island is an abandoned island off the coast of Nagasaki, Japan. It earned the nickname “Gunkanjima” or “Battleship Island” because its dense cluster of concrete buildings, when viewed from a distance, resembles a warship.

When was Hashima Island active and why was it abandoned?

The island was primarily active between 1890 and 1974 as a coal mining site owned by Mitsubishi. It was abandoned after Japan shifted to petroleum-based energy and coal demand sharply declined.

How have artists portrayed the island’s history of forced labor?

Contemporary Korean and Chinese artists have used installations and symbolic media to address the suffering of conscripted workers during World War II. Their work often contrasts with more subdued Japanese representations.

Has Hashima been featured in films or anime?

Yes, most famously as inspiration for the villain’s lair in Skyfall (2012). It has also appeared in Japanese films like Battle Royale II and influenced settings in manga and anime, including Attack on Titan and One Piece.

Can tourists visit Hashima Island today?

Yes, since 2009, guided boat tours have been allowed to land on a designated part of the island. Visitors cannot enter buildings due to safety risks, but the visit offers a powerful visual experience.