Long before Geneva became a Calvinist stronghold or a diplomatic enclave, it was a patch of lake-silt and glacial stone, inhabited by a succession of peoples who left no names but left marks nonetheless. The story of art in Geneva begins millennia before the city itself—when image, craft, and ritual first began to shape the human relationship to place in the region around the western shore of Lake Léman.

The Lakeshore Mind: Neolithic Settlements and Symbolic Craft

In the shallows and wetlands near what is now the quartier des Eaux-Vives, archaeologists have uncovered the remnants of Neolithic pile-dwelling villages—timber structures raised on stilts above the lake’s edge. These settlements, dating as far back as 4000 BC, are part of a wider Alpine lacustrine culture that left behind a network of stilt-house communities stretching from northern Italy to Bavaria. In 2011, the site was recognized as part of the UNESCO World Heritage collection of “Prehistoric Pile Dwellings around the Alps.”

What matters for art history is not just the architecture of these vanished villages, but what their remains reveal about early symbolic life. The pottery shards recovered from Geneva’s lakeside zones are not utilitarian blanks. Many are burnished, painted, or incised with rhythmic, geometric patterns—zigzags, spirals, crosshatches. These were not mere flourishes. They suggest a cognitive world where symmetry, repetition, and surface design carried meaning—whether magical, communicative, or ritual.

Stone tools, too, show signs of formal consideration. Certain axe heads, for instance, were ground with such polish and symmetry that their function as tools seems almost secondary. They may have served as status objects, or tokens in exchanges between tribal groups—proto-artifacts of visual identity.

Even more revealing are the so-called schematic figurines—small anthropomorphic carvings found near the Geneva basin and across the Alpine region. These are abstracted, nearly anonymous forms: wide-hipped, faceless, carved in bone or clay. While there is no direct evidence of their use, their presence in burial contexts suggests a ritual or funerary purpose. In their stripped-down form, they offer the first known gestures toward figurative representation in the area now called Geneva: a body reduced to shape, but retaining presence.

Alluvial Orders: Celtic Ritual, La Tène Style, and the Rhône

By the Iron Age, the Geneva region had become part of the cultural orbit of the La Tène civilization—a Celtic culture centered near modern-day Lake Neuchâtel. From roughly 500 BC until the Roman conquest, the people who inhabited this region combined mobility with craft sophistication, especially in metalwork and ornamentation. Here, art emerged not on walls or statues, but in personal objects: weapons, jewelry, and ceremonial tools forged with astonishing intricacy.

La Tène art is curvilinear and restless—full of swirling motifs, vegetal patterns, and abstract animal forms. Geneva’s position near the mouth of the Rhône placed it in a network of trade and cultural exchange linking the Alps to the Mediterranean, and La Tène artifacts found in the area include bronze torcs, fibulae (brooches), and decorative scabbards. These were not decorative in the modern sense; they were signifiers of identity, lineage, and supernatural protection.

The Rhône itself had religious significance. Early tribal sanctuaries—likely constructed of wood and earth—were erected near riverbanks, and votive deposits (weapons bent and cast into water) suggest a practice of ritual offering to aquatic or chthonic deities. In this context, art was inseparable from violence, belief, and the landscape itself. To inscribe, carve, or cast was not to adorn but to bind a gesture into matter.

One of the most intriguing finds near Geneva is a Celtic helmet fragment in repoussé bronze, etched with stylized beasts and knotwork. It almost certainly belonged to a high-status warrior, but its design suggests more than rank: it was part of a visual cosmology, a portable mythology worn into battle. This is not narrative art in the classical sense, but symbolic visual language—compressing belief into ornament.

Colonia Iulia Equestris: Rome’s Visual Imprint on the Lemanic Basin

The decisive visual transformation came with the Roman conquest. Around 120 BC, Geneva was absorbed into the Roman sphere, and by the time of Julius Caesar it had become a known waypoint in his Gallic campaigns. Though Geneva itself remained a small outpost, the nearby city of Colonia Iulia Equestris (modern Nyon) emerged as the Roman regional capital—complete with a forum, basilica, baths, and amphitheater. Geneva, while peripheral, still bore the stylistic and administrative imprint of the Roman system.

Romanization brought stone construction, sculptural programs, and above all, a new grammar of public space. Inscriptions, statuary, and architectural decoration—columns, friezes, carved capitals—began to appear where none had existed before. Art shifted from private ritual to imperial display. The gods were now adorned with togas and laurel wreaths. The human form took on idealized proportions. Realism, hierarchy, and symmetry dominated the visual culture.

Fragments of Roman Geneva remain: coin hoards stamped with imperial visages, domestic fresco remnants in red and ochre, and sections of mosaic flooring hinting at Dionysian imagery or geometric illusionism. A limestone altar recovered near the Parc des Bastions bears a Latin dedication to Jupiter Optimus Maximus—the Roman sky-god enthroned above the conquered landscape. This was not merely a shift in iconography, but a cultural conquest rendered in stone and pigment.

Notably, Roman art in Geneva was not confined to temples or elites. Terracotta oil lamps, glass vessels, and stamped pottery with decorative motifs found in middle- and lower-class dwellings suggest that visual refinement trickled through the entire social fabric. Art became part of the domestic economy. The image of the imperial eagle was stamped as casually onto a bowl as onto a banner.

And yet, even at the height of Roman order, there were continuities with the past. Local artisans continued to embed older, Celtic motifs into new Roman forms—an example of stylistic layering rather than replacement. Geneva’s visual identity was never purely imposed from above; it absorbed, distorted, and repurposed what it was given.

The prehistoric and Roman epochs of Geneva tell a story not of silence, but of slow accumulation—a visual vocabulary built from clay, bone, metal, and stone. There were no museums, no manifestos, no aesthetic philosophies. But there were choices, patterns, symbols, and marks—each one a negotiation between material and meaning. Before Geneva was a city of reform or refuge, it was already a site of images: submerged, portable, ritual, and architectural.

The Gothic world would later drape itself across this foundation, building cathedrals where votive rivers once flowed. But Geneva’s art begins here: in the mud, the fire, and the glitter of bronze.

The Gothic Foundations: Civic Ornament and Sacred Symbol

Geneva’s Gothic period began not with a cultural awakening, but with a political assertion. By the 12th century, it was no longer a marginal Roman outpost but a fortified episcopal seat, increasingly autonomous from imperial overlords and regional dukes. At its center stood the bishop—not just a religious figure, but a territorial ruler whose authority extended across the countryside. In this context, art was not an accessory to devotion. It was an instrument of power.

Stone and Psalm: Early Ecclesiastical Patronage

The single most enduring monument from this era is the Cathédrale Saint-Pierre, a structure that absorbed centuries of ambition, revision, and restraint. Its foundations stretch back to the 4th century, but the Gothic overhaul began in earnest during the late 12th century under Bishop Arducius de Faucigny. The architectural vocabulary—pointed arches, ribbed vaults, clerestory windows—was not just stylistic fashion. It announced alignment with the cultural heartlands of Christendom.

The cathedral’s sculptural program, though severely damaged by later iconoclasm, would have followed the theological currents of its age. Tympanums, capitals, and choir stalls once bore carved saints, biblical narratives, and grotesques—all part of the medieval grammar of visual instruction. This was a city where fewer than ten percent could read Latin, yet everyone could read a sculpted Last Judgment.

Surviving elements hint at a richer past: fragments of polychrome stone, traces of gilding, the remains of a rose window whose radiating petals once mimicked divine symmetry. These were not mere embellishments. They were modes of theological participation. To decorate a church was to honor God; to commission a chapel was to secure one’s salvation.

A less visible but equally significant layer was the architecture of sound. Gothic Geneva was a city of choral offices, bells, and plainsong. The cathedral interior was shaped not only for the eye but for the ear—its vaults designed to carry chant, its stone surfaces tuned to echo psalms. Artistic design extended to acoustics.

The bishopric’s patronage went beyond the cathedral. Churches like Notre-Dame-la-Neuve and Sainte-Claire, now mostly vanished, once dotted the medieval map of Geneva. Each one carried its own program of murals, liturgical furnishings, and altarpieces. Their loss is not just architectural—it is a loss of worldview, of local saints and civic intercessors whose images once lined the nave.

Masons, Manuscripts, and the Maison Tavel

While ecclesiastical art dominated public life, the Maison Tavel—today Geneva’s oldest surviving domestic structure—offers a rare portal into the visual language of elite households in the 13th and 14th centuries. Originally built by a patrician family and later rebuilt after the devastating fire of 1334, the house reveals how visual culture filtered into secular architecture.

Though stripped of its original furnishings, architectural traces remain: carved corbels, ribbed vaults in the cellar, and a heraldic fresco painted directly onto the stone. In the Middle Ages, such homes were not purely functional. They were statements of lineage, allegiance, and urban status. Coats of arms, religious shrines, and decorative motifs served as both ornament and communication—signaling alliances in the city’s turbulent political landscape.

Decorative objects, too, circulated through Geneva’s mercantile networks. Archival records describe imported goods from Italy and Flanders: embroidered altar cloths, painted triptychs, and tapestries depicting scenes from the Old Testament or courtly romance. These weren’t museum pieces—they were embedded in the life of the household. A triptych might be closed six days of the week, opened only on feast days. A tapestry served to insulate a wall while displaying dynastic pride.

Geneva’s scriptoria also played a role in cultivating visual literacy. While not as prolific as the great monastic centers of Cluny or Reichenau, Geneva’s cathedral chapter maintained a modest manuscript tradition. Illuminated missals, psalters, and breviaries were copied for use in the liturgy. Marginalia—often whimsical or grotesque—revealed the human hand behind the sacred word: hybrid creatures, snails in joust, monks at table.

These were not acts of rebellion, but of imagination. Even within the narrow lanes of dogma, the medieval artist found room for play.

Geneva Before the Reformation: A Fragile Opulence

The late Gothic period brought a sense of maturation—and vulnerability. From the 14th through the early 16th century, Geneva’s artistic life reached a measured richness, bolstered by merchant wealth and the city’s growing independence from the counts of Savoy. And yet this flowering occurred under a shadow. Plague cycles, economic instability, and religious tension created a precarious cultural environment.

One of the few large-scale artworks to survive from this period is a fragmentary mural from a cloister wall near the cathedral. It depicts the Virgin in a mandorla, flanked by saints, with a strip of cityscape beneath her feet—Geneva rendered as both earthly domain and sacred refuge. The stylistic influence is Burgundian, suggesting either imported artists or local craftsmen trained abroad.

Three elements characterized Geneva’s late Gothic aesthetic:

- A restrained opulence: stained glass in deep but limited palettes, emphasizing spiritual clarity over sensual lushness.

- An emphasis on didactic clarity: wall paintings served catechetical function, visually reinforcing sermons.

- A blending of civic and sacred motifs: saints sometimes appeared in local garb, and biblical scenes were set against Geneva’s skyline.

This hybridization was deliberate. The city was aligning itself with the moral seriousness of northern Europe while maintaining connections to the visual traditions of France and Italy. Artistic commissions were often group endeavors, funded by guilds or confraternities rather than single aristocratic patrons. In this sense, Geneva’s art began to express a collective urban identity, not just a feudal one.

But this fragile balance was short-lived. By the early 1500s, theological conflict was intensifying. The printing press brought new doctrines; sermons turned polemical. In 1535, less than a decade before John Calvin’s arrival, the city erupted in iconoclasm. Statues were torn from niches. Altarpieces were smashed. Paintings were burned in public squares. It was a coordinated rejection—not just of corruption, but of image itself.

What was lost in that moment was incalculable. Geneva’s entire medieval visual heritage was reduced to fragments—some buried in crypts, others plastered over, many destroyed entirely. And yet these ruins still whisper. A chipped column, a fresco hidden beneath limewash, a carved capital embedded in a garden wall—these remnants are more than debris. They are the memory of a visual world violently renounced.

Geneva’s Gothic age was never as flamboyant as Rouen or Chartres, but it was rooted, coherent, and deeply civic. Its visual tradition emerged not from court excess but from theological purpose and urban ambition. In losing it, Geneva did not become blank. It became haunted.

Iconoclasm and Restraint: The Calvinist Revolution in Image

The Reformation did not arrive in Geneva as a gradual realignment of faith. It came as a rupture—violent, abrupt, and architecturally disfiguring. By the middle of the 16th century, Geneva had not only broken with the Roman Church but had begun remaking itself as the ideological capital of European Protestantism. Its transformation was theological, political, and aesthetic. And its most dramatic expression was what it destroyed.

The 1535 Iconoclasm and Its Shockwaves

The year 1535 marked a turning point. As tensions between reformers and the Catholic establishment escalated, the city council authorized the removal of “idolatrous images” from all places of worship. What followed was swift and thorough: statues were smashed, altarpieces pulled from walls, stained glass shattered, murals whitewashed, and reliquaries desecrated. The great cathedrals and chapels that had once dazzled with color and narrative were reduced to bare stone and wood.

This was not a riot of the unthinking. It was an organized campaign, driven by conviction and coordinated through the new apparatus of the Reformed city-state. The cathedral of Saint-Pierre, once adorned with saints and angels, was stripped almost to its architectural skeleton. The space was not desecrated, in the eyes of its reformers—it was purified.

Three motivations underpinned this wave of iconoclasm:

- Theological objection: Calvin and his followers viewed religious images as distractions at best, idolatrous corruptions at worst.

- Moral discipline: Art was associated with sensory indulgence, and Geneva’s reformers sought to curb all avenues of aesthetic excess.

- Political assertion: The destruction of images was a visible claim to autonomy—not only from Rome but from the visual languages of empire, nobility, and Catholic tradition.

It’s tempting to think of this as a cultural blank slate, but that’s misleading. What the Reformation imposed was not the end of image, but its redirection. The visual field didn’t disappear—it narrowed, hardened, and went underground.

Calvin’s Theology of the Visual: Suspicion and Control

John Calvin arrived in Geneva in 1536, just a year after the iconoclasm, and he institutionalized what had begun in fury. His theology placed deep suspicion on the visual imagination. In his Institutes of the Christian Religion, he wrote: “A true image of God is not found in all the world, and hence His glory is defiled by the lies of every representation.” For Calvin, to picture the divine was to lie about it.

This suspicion translated into architectural and artistic reform. Churches were redesigned as preaching halls—long, narrow spaces oriented toward the pulpit, not the altar. The spoken Word, not the visual image, became the organizing principle of space. Walls were bare, light was unfiltered, and ornament was stripped to the minimum necessary for structure.

Yet Calvin was not a crude anti-aesthetic. He allowed for the use of printed Bibles, approved musical psalmody, and even permitted scientific illustration and secular art in private homes. His concern was not with image in itself, but with image in the wrong place—particularly in public, religious, or political settings where it might provoke devotion or stir vanity.

In this climate, art did not disappear. It became quiet. Portable. Coded. Artists shifted their attention to:

- Book illustration, especially theological texts and moral allegories.

- Domestic decoration with geometric, floral, or landscape motifs—non-narrative and unprovocative.

- Craft and ornamentation in objects of utility: watch cases, furniture inlay, woven textiles.

Visual expression in Calvinist Geneva was thus not extinguished, but disciplined. The city became a laboratory for what image might become when shorn of both sensuality and spectacle.

The Persistence of the Decorative in a Culture of Denial

Despite official suspicion, Geneva did not become a grey box. Decorative impulse reasserted itself in quieter forms, particularly in the applied arts. Watchmakers, goldsmiths, and cabinet-makers continued to innovate—embedding miniature enamel paintings inside locket covers or elaborating woodwork with subtle biblical references. The visual imagination didn’t die. It learned to whisper.

One of the most revealing artifacts of the era is a 16th-century Psalter printed in Geneva by Jean Crespin. Its margins contain elegant, restrained woodcuts—allegorical emblems, stylized vines, symbolic animals—all tightly controlled but unmistakably crafted to move the reader’s eye. Even in the austere world of Calvinist publishing, there was room for design.

Geneva also developed a taste for moral emblem books, which paired cryptic images with didactic verses. These works—part puzzle, part meditation—offered a visual language compatible with Reformed theology: metaphorical, indirect, and text-dependent. They invited reflection, not adoration.

A subtle culture of interiority began to dominate. The image was not to teach doctrine through grandeur, but to prompt self-examination through subtlety. This shift had long consequences. In Protestant Geneva:

- A landscape painting could function as a metaphor for spiritual isolation.

- A still life could evoke mortality without reference to saints or scripture.

- A piece of furniture, if well made, could serve as a quiet testimony to order, restraint, and divine providence.

This ethos was not universal. Some resisted it, others circumvented it, and artists of Catholic background who fled the city often remarked bitterly on its visual poverty. But Geneva’s internal visual culture—like its theology—was not superficial. It demanded attention, and in return, offered complexity.

The Reformation in Geneva was not just a change in doctrine. It was a forced reorientation of the eye. Public art was dismantled; private art was muted. The image did not disappear, but it had to justify its existence—quietly, rationally, and often behind closed doors. In the ashes of the altarpiece, a new visual culture emerged: austere, encrypted, and morally charged.

That restraint would come to define Geneva’s artistic self-image for centuries. But it was never absolute. Even in Calvin’s city, the artist never disappeared. He simply changed his tools.

Subterranean Aesthetics: Protestant Print Culture and the Engraved Line

If the Reformation emptied Geneva’s churches of images, it filled its workshops with them. The destruction of sacred art did not suppress visual expression entirely—it displaced it, forcing it into smaller, more deliberate forms. In a culture where sculpture and fresco were suspect, the printed page became the new canvas. There, behind the justification of scripture and the shield of scholarship, a subterranean visual culture thrived—precise, allegorical, and deeply Protestant.

From Altarpiece to Etching: Redirecting the Artistic Impulse

By the mid-16th century, Geneva had become a magnet for Protestant printers, engravers, and typographers, many of them exiles from Catholic territories. Their task was ostensibly textual: to publish editions of the Bible, theological commentaries, sermons, and polemics. But the work of these presses soon gave rise to a distinct visual style—one shaped as much by constraint as by invention.

In the absence of large-scale public commissions, artistic energy turned to woodcut and copperplate engraving—media well suited to both reproduction and discretion. These were arts of line rather than mass, of ink rather than pigment. Instead of vaulting ceilings and radiant saints, the artist now carved moral symbols into a block of fruitwood or etched shadow into a fine copper sheet.

One figure central to this transformation was Pierre Eskrich, a Lyon-born Protestant who settled in Geneva after fleeing persecution. His woodcuts, often illustrating theological works or emblems of virtue and vice, combined anatomical precision with emblematic clarity. The compositions were spare, but never dull. Every fold of cloth, every furrow of earth, carried significance. The visual field was stripped of excess and saturated with meaning.

Another was Jean de Laon, known for his engravings of biblical scenes reframed through a Protestant lens. In his version of the Last Supper, Christ appears not at the head of a mystical table but among plain men, seated as equals—a subtle shift from sacrament to teaching moment. It was not just doctrine that had changed, but composition.

This era also saw the emergence of printed emblem books—albums that combined images and epigrams to explore virtues, vanities, and spiritual trials. Widely circulated among Geneva’s literate elite, these books provided a new kind of devotional art: contemplative, interpretive, and entirely suited to the private interior. In Geneva, the moral imagination found its form not in stained glass, but in metaphor rendered on the printed page.

Plantin, Estienne, and the Illustrated Bible

One of the most potent vehicles for post-iconoclastic visual art was the illustrated Bible, and Geneva was a leading producer. The most influential edition was the Geneva Bible, printed first in 1560 and distributed across Europe, especially in England and Scotland. Though the Geneva Bible was more famous for its annotations than its images, later editions incorporated woodcut illustrations of key biblical moments: Noah’s Ark, the Exodus, the Crucifixion.

These images were not lush or celebratory. They were didactic, schematic, even severe. A woodcut of the Flood might show not swirling water and terrified faces, but a tidy procession of animals, each labeled and orderly. The artist’s hand was subordinated to the clarity of the message.

The printers behind these works were men like Robert Estienne and Christophe Plantin, both of whom established networks connecting Geneva to the major Reformed centers of Leiden, London, and Basel. Their output was immense—Bibles, Psalters, Calvin’s Institutes, Greek grammars, Hebrew lexicons—all interspersed with modest yet powerful illustrations.

In this world, even typeface became an aesthetic choice. The Geneva style of typography—clear, angular, unornamented—mirrored its theological purpose. Legibility was a form of moral clarity. Beauty, where it appeared, emerged from proportion and restraint.

Yet within these constraints, there were moments of genuine grace. An initial letter might bloom into a vine. A chapter heading might frame a scene of quiet pastoralism. These were not flourishes in the Catholic sense—they were acts of attention. In Geneva, the artist survived in the margins.

The Rise of the Protestant Image: Allegory, Emblem, and Morality

What Geneva’s visual culture lost in sensuality, it gained in compression. The Protestant image, banned from public worship, became an art of symbols. Allegory flourished. Emblem books such as Andrea Alciato’s Emblemata and its Genevan imitations gave readers a new form of visual thought: image, motto, and explanatory verse bound together in a tripartite argument.

These emblems addressed everything from political virtue to divine justice, often in startling combinations. A shipwreck might stand for human pride. A chained dog might symbolize restraint. A broken column might evoke the fragility of wisdom. In these images, meaning was not declared—it was constructed by the viewer, an approach fully aligned with Reformed suspicion toward passive religious consumption.

The private citizen became both reader and interpreter. Emblematic art was not for worship but for reflection. And because it lived in books, not buildings, it could be owned, annotated, passed between friends. Geneva became a city of marginalia.

Three forms dominated this culture:

- Moral allegory: Images that condensed ethical dilemmas into symbolic forms, often echoing biblical parables.

- Didactic sequence: Illustrated narratives—such as The Life of Christ or The Seven Ages of Man—presented in controlled, segmented panels.

- Natural metaphor: Trees, animals, and seasons used to convey human virtues and vices, with roots in both biblical and classical traditions.

This kind of art required literacy, patience, and an inclination toward abstraction. It offered no raptures. But it also made no demands for obedience. It asked only that the viewer look, think, and perhaps be moved.

Geneva’s post-Reformation visual culture has often been misunderstood as a vacuum, a desert of suppressed creativity. But this is wrong. Its art did not vanish. It relocated—into the printed page, the private study, the emblem, the metaphor. Its visual discipline was not born of poverty but of principle. The artist survived in Geneva—not as a painter of saints, but as a carver of woodblocks, a cutter of copper, a constructor of moral diagrams.

What emerged from this quiet revolution was a new kind of visual intelligence: restrained but rich, silent but precise, utterly compatible with a theology of suspicion. In the shadows of destroyed altarpieces, the line replaced the icon. And Geneva, against all odds, became one of the most important cities in the history of the illustrated book.

Watchmakers and Miniaturists: The Art of Precision

As Geneva’s churches remained stripped and its walls austere, another kind of artistry quietly flourished behind shuttered windows and under magnifying glasses. In the 17th and 18th centuries, visual expression in Geneva turned decisively toward the intimate, the mechanical, and the minute. The Reformed suspicion of religious imagery had not vanished, but it had evolved. It no longer required silence—it required discretion. And in this climate, the artisan rose to cultural prominence: the watchmaker, the miniaturist, the enameller, the cabinet-maker.

Nowhere was this more visible—or more refined—than in the art of precision.

Craft as Concealment: Art in Calvinist Geneva’s Private Interiors

Geneva’s sumptuary laws, especially in the post-Reformation centuries, discouraged overt displays of wealth or sensual indulgence. Facades remained plain, and public spaces were carefully regulated. But inside the homes of merchants, magistrates, and financiers, a different story unfolded. Here, behind closed doors, the Genevan elite cultivated a culture of private beauty—delicate objects that combined refinement with restraint.

Cabinets, writing desks, and devotional boxes were often elaborately inlaid with marquetry—complex mosaics of wood, ivory, mother-of-pearl, and tortoiseshell. Still lives were sometimes hidden beneath folding panels. Drawer interiors were lined with painted scenes—classical landscapes, genealogical emblems, or discreet biblical allegories. These were not for public consumption. They were made to be opened, examined, and quietly admired.

In some homes, painted wall panels featured subdued landscape scenes or moral tableaux in grisaille—a monochrome style imitating sculpture, favored for its perceived austerity. The eye was drawn not by color or movement, but by form and message. Art became contemplative rather than declarative, a shift consistent with Geneva’s theological climate.

This was not hypocrisy. It was a recalibration of values. Beauty was permitted—but only if it carried the scent of utility, or the humility of scale.

From Dials to Portraits: Enamel Painting and Microscopic Art

The most brilliant convergence of theology, commerce, and visual sophistication occurred in enamel painting, particularly as applied to watches. Geneva had become, by the late 17th century, one of Europe’s premier centers for horology—an industry born partly from refugee labor, partly from the city’s own Calvinist ethic of discipline, punctuality, and productive time.

Genevan watchmakers, many of them descendants of Huguenots who had fled France after the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685, combined mechanical ingenuity with painterly skill. The result was the enamelled watch case, often no larger than a plum, yet containing intricate images of astonishing finesse.

Artists like Jean Petitot elevated the medium to extraordinary levels. Born in Geneva in 1607, Petitot trained as a goldsmith before turning to enamel portraiture. His works, many of which were commissioned by the French and English courts, depicted aristocratic sitters in luminous, microscopic detail—layers of pigment fused onto a metal base through successive firings. The technical challenge was enormous: a single misstep in heating could crack the image irreparably.

Petitot’s portraits are striking for their polish and intimacy. Unlike oil portraits meant for gallery display, these were often kept close—worn as lockets, held in hand, or tucked into writing desks. The result was a portable image culture, one that suited Geneva’s ambivalence toward large-scale public art. What could not be shown on a cathedral wall could still be hidden beneath a watch cover.

Even secular themes—mythological scenes, pastoral landscapes, literary vignettes—found their way into these objects. But they did so filtered through scale and refinement. A Venus or Apollo might appear, but reduced to a cameo, painted with such restraint that sensuality gave way to elegance. Geneva, ever suspicious of theatricality, made room for classicism only when miniaturized.

Three defining characteristics emerged from this culture of enamel and miniature:

- Compression: Images were reduced in scale but not in complexity; the painter’s challenge was to say more with less.

- Privacy: Artworks were designed for intimate spaces—watches, snuffboxes, medallions—not public display.

- Portability: Objects could cross borders and confessional lines, allowing Genevan artisans to sell discreetly to Catholic patrons without violating their own city’s norms.

This form of art—dense, coded, portable—became one of Geneva’s most important cultural exports. And it subtly subverted the old Calvinist ban on image: here was beauty, rendered not obsolete but internal.

Horology as Artform: Mechanism, Symbol, and Ornament

By the 18th century, Geneva had become synonymous with fine watchmaking, not merely as an industrial pursuit, but as an aesthetic one. The city’s horological ateliers were organized through strict guilds, each responsible for a different part of the process—case-making, dial painting, escapement regulation. The result was a collective craft that blurred the line between utility and ornament, precision and art.

Time itself had theological resonance in Geneva. The Reformed worldview placed great emphasis on order, stewardship, and the fleeting nature of life. The watch became more than a tool—it became a symbol of discipline, a wearable memento of mortality and vigilance. Geneva’s most refined timepieces often bore inscriptions or allegorical engravings: Time with a scythe, the Seasons in rotation, or an hourglass flanked by vanitas symbols.

The métiers d’art associated with watchmaking—champlevé enamel, guilloché engraving, gem-setting—allowed for remarkable visual innovation within small physical limits. An 18th-century watch might include:

- A pastoral scene on the back case, hand-painted in miniature enamel.

- A dial inlaid with mother-of-pearl, its indices painted in Roman or Arabic numerals.

- An internal mechanism engraved with a Latin motto visible only upon disassembly.

These were not the indulgences of idle aristocrats. They were cultural statements: that beauty could be reconciled with utility, that time could be moralized, that art could inhabit a circle the size of a coin.

Even today, the legacy of these crafts survives in the haute horlogerie houses of Geneva—names like Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin—who continue to balance mechanical rigor with visual splendor. But their foundations lie in this earlier, quieter era, when a city uncomfortable with painting found a way to smuggle art into the pocket.

In a world stripped of fresco and gilded saints, Geneva discovered a new kind of image: precise, intimate, and perfectly timed. The art of the miniature offered a paradoxical solution to the Reformed dilemma—beauty without spectacle, image without idolatry. And in doing so, it gave Geneva its most enduring artistic identity: not as a city of grand canvases, but as a place where the image survived in exquisite reduction.

A Republic of Refugees: Art in the Age of Migration

Geneva’s artistic history is not one of great dynasties or flamboyant academies. It is a history of adaptation—of restraint shaped by conviction, and of refinement shaped by exile. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, when the city received a vast influx of refugees—primarily French Huguenots fleeing Louis XIV’s persecution. Geneva, already a Protestant stronghold, became a cultural refuge. And with these migrants came skills, tastes, and objects that would quietly but decisively shape the city’s visual and material identity.

Huguenot Flight and the Transmission of French Taste

The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 triggered one of the largest religious migrations of early modern Europe. Tens of thousands of Huguenots fled France—many with commercial expertise, artistic training, or artisanal skill. Geneva, with its Reformed character and long-standing ties to the French-speaking world, became one of their primary destinations. In the decade following the Revocation, the city’s population swelled, and its workshops filled.

These refugees did not arrive empty-handed. Many carried books, tools, textiles, and religious artifacts. Others brought knowledge that would reshape Geneva’s artisanal infrastructure. Huguenot goldsmiths, cabinet-makers, and textile printers introduced new techniques and stylistic vocabularies, blending French baroque delicacy with Genevan sobriety. The result was a distinct hybrid: elegant, minimal, and portable.

One of the most important transformations occurred in the realm of domestic interior design. Where Genevan homes had once favored Calvinist austerity—whitewashed walls, bare floors, minimal decoration—new influences introduced richer materials and refined ornamentation. Wall panels were painted with muted pastoral scenes. Furniture gained curvature and inlay. Curtains, previously rare, appeared in damask and silk.

Huguenot refugees also contributed to literary and graphic arts, founding print shops and bookstores that distributed Bibles, psalters, and political pamphlets across Protestant Europe. Their typographic styles—often echoing the sophistication of Parisian design—introduced visual elegance into a world previously wary of embellishment.

Though Geneva remained committed to visual restraint in public, the private sphere became a site of subtle flourish. Homes of well-off refugee families often included:

- Miniature oil portraits set into wooden frames, displayed in intimate spaces like studies or dressing rooms.

- Lacquered cabinets with chinoiserie motifs, evidence of both French taste and international trade.

- Hand-embroidered linens and wall textiles featuring symbolic patterns—grapevines, lilies, or scriptural quotes—combining utility with meaning.

These were not courtly luxuries. They were artifacts of exile: portable, layered with memory, and designed to survive scrutiny.

Silk, Silver, and Subtlety: Material Culture in the Refugee City

Among the most significant Huguenot contributions was the revival and diversification of Geneva’s luxury trades—particularly in silk weaving, silverwork, and printed textiles. These crafts allowed displaced artisans to reestablish livelihoods while reshaping the visual economy of the city.

The silk trade, long suppressed under Calvinist suspicion of vanity, found new legitimacy when framed as export-oriented and industrious. Huguenot weavers established looms in the Faubourg district, producing ribbons, lace, and lightweight patterned fabrics. These were not flamboyant satins or ecclesiastical brocades—they were restrained, but elegant, suitable for Protestant dress and merchant-class interiors.

Silverwork also flourished. While large ecclesiastical commissions were no longer possible in Geneva, domestic silver objects became prized: candlesticks, tea services, tobacco boxes, and snuff spoons. These items were often engraved with coats of arms, scriptural verses, or emblematic motifs—a balance of craftsmanship and moral instruction. Decorative, yes, but never ostentatious.

The textile printers of Geneva—many trained in Lyon or Avignon—began producing toiles imprimées, or printed cottons, using woodblock and copperplate methods. Scenes from scripture, classical mythology, and pastoral life were rendered in monochrome or two-tone schemes, suitable for bed hangings, upholstery, and decorative screens. The visual style was illustrative, never theatrical—Geneva had no taste for rococo excess.

What bound these arts together was a shared ethic: beauty filtered through moderation, ornament disciplined by purpose. The city, shaped by loss and migration, began to develop a visual language of resilience—grace without grandeur.

Protestant Cosmopolitanism: Dutch, English, and Italian Influences

Though Huguenot refugees were the most visible cultural force in this period, Geneva’s artistic networks extended far beyond France. The city’s status as a hub of Protestant diplomacy and publishing brought it into contact with Dutch, English, and northern Italian traditions—each of which left their mark.

Geneva’s book publishers began importing engravings from Amsterdam and Leiden, bringing with them the cool clarity of Dutch Protestant iconography. Illustrated theological treatises often featured landscapes and architectural scenes in the Dutch style—spare, controlled, rational. Moral allegories were cast in rural settings: the vineyard of the soul, the narrow path, the city on the hill.

From England came both buyers and designs. Genevan watchmakers, already known for their precision, began tailoring models for English clientele—some engraved with Psalmic quotations, others featuring royalist emblems. Even the shape of timepieces began to shift, responding to English tastes for flatter, oval forms.

Italy provided both caution and inspiration. While Catholic baroque style was viewed with suspicion, certain elements—especially in technical drawing, anatomy, and classical proportion—filtered through Protestant intermediaries. Italian prints were collected in Geneva’s libraries and study cabinets, studied for their structure if not their subject matter.

This convergence of influences produced what could be called a Protestant cosmopolitanism—not flamboyant, but eclectic and informed. Geneva’s visual culture now bore the marks of exile, trade, and theology, all layered into a uniquely cautious form of sophistication.

Three Geneva-specific developments arose from this synthesis:

- The internationalizing of craftsmanship: objects made in Geneva were designed to travel and to speak across cultures.

- A neutralized symbolism: rather than saints or miracles, art used time, nature, and labor as visual metaphors.

- A migration of the sacred: religion moved from public display into private possession, from the altarpiece to the object in hand.

The art of refugee-era Geneva is easy to overlook. It hides in drawers, ticks on wrists, and rests quietly on embroidered pillows. But it marks a profound cultural moment: a city redefined not by what it expelled, but by what it absorbed. In the absence of empire or cathedral, Geneva built its visual world through migration, memory, and the disciplined hand of the artisan.

In doing so, it proved that austerity need not mean poverty. And that from exile can come elegance.

Rousseau’s Shadow: Romanticism and the Natural Sublime

In the late 18th century, Geneva’s austere visual culture collided with a new force: emotion. The Enlightenment, with its emphasis on reason and measure, had never been entirely comfortable in Geneva’s Protestant shell. But it had found a place. By contrast, Romanticism—the stormier sibling of the Enlightenment—arrived like a disturbance in the Genevan order. It brought a different kind of image: wild mountains, weeping figures, ruins, storms, solitary walkers. And at its center stood Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the city’s most paradoxical son.

Rousseau was not a visual artist, but no figure in Genevan history has shaped its aesthetic imagination more deeply. He turned the city’s landscape into metaphor, its exile into moral critique, and its natural surroundings into a theatre of the sublime. His influence lingers in brushstroke and skyline long after his political writings faded from fashion.

The Return to Landscape: Geneva and the Alpine Gaze

Geneva had always lived in the shadow of mountains, but in the centuries of Reformed vigilance, the landscape had remained largely symbolic—an emblem of divine order, or a background to moral narrative. With the rise of Romanticism, this shifted. Nature became central, not peripheral. And the Alpine panorama surrounding Geneva, once viewed as scenic but stable, was reinterpreted as sublime: awe-inspiring, threatening, unmasterable.

This transformation was both artistic and emotional. The painters François Diday and his student Alexandre Calame, though better associated with the mid-19th century, owed much to the Romantic shift Rousseau had initiated. Their vast canvases of snowy passes, glacial torrents, and jagged peaks did more than describe Swiss geography—they dramatized it. Nature was no longer a passive setting but an active subject.

Earlier Geneva artists had painted landscapes as moral spaces—tame, cultivated, infused with metaphor. Diday and Calame, in contrast, painted nature’s violence and beauty without allegory. Their mountains erupted from the canvas. Trees bent under wind. Valleys disappeared into cloud. The viewer was not outside the scene, but within it, overawed and disoriented. This was Rousseau’s effect made visible: the human being, small and uncertain, confronted by nature’s enormity.

Three defining traits emerged in Geneva’s Romantic landscape tradition:

- Elevated vantage: many works are composed from cliffside or mountaintop, emphasizing vertigo and expanse.

- Atmospheric detail: cloud, mist, and light become protagonists; the mood of a painting often hinges on a single patch of sky.

- Absence of figures: human presence, if included at all, is tiny, peripheral—reaffirming nature’s primacy.

These were not mere aesthetic choices. They were philosophical. In Rousseau’s Geneva, nature was no longer a decoration of faith. It was a substitute for it—a source of truth, emotion, and even redemption.

Delacroix, Hodler, and the Politics of the Sublime

The Romantic turn was not limited to landscape. It bled into portraiture, historical painting, and public memory, infusing Geneva’s visual culture with a sense of drama that had long been discouraged. One of the more surprising figures to engage with Geneva was Eugène Delacroix, who spent time in the city in the 1820s and whose journals record both fascination and discomfort with its Calvinist severity.

Delacroix never painted Geneva directly, but his influence was felt. The emotional charge of his brushwork—his willingness to render suffering, ecstasy, and chaos—resonated with younger Genevan artists eager to break free of didactic restraint. One of them was Ferdinand Hodler, born in nearby Bern but deeply shaped by the city. Though working slightly later, Hodler’s symbolic murals and monumental figures belong to this same Romantic lineage.

Hodler’s Retreat from Marignano (1897), a massive historical painting now in Geneva’s Musée Rath, exemplifies the convergence of national myth, emotional gesture, and aesthetic sublimity. The painting shows Swiss soldiers—bareheaded, wounded, exhausted—turning away from battle. There is no triumph, only endurance. The mountain backdrop looms like a moral force, indifferent to human valor.

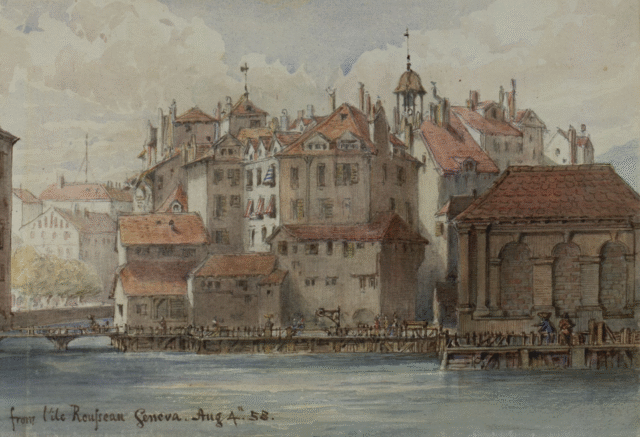

Even Geneva’s monuments began to adopt this tone. In 1835, on the centenary of Rousseau’s birth, the city erected a statue of him on Île Rousseau, facing away from the Old Town. The pose is contemplative, the gesture understated. But the message was clear: Geneva, once the city that banished him, now claimed him as its prophet. The monument became a visual hinge between Calvin’s restraint and Rousseau’s reverie.

Rousseau’s legacy also changed how artists approached interior emotion. Romantic portraiture in Geneva became softer, more atmospheric. Light played across skin with gentle chiaroscuro. Subjects appeared not as moral exemplars, but as individuals—flawed, reflective, emotionally legible. The Reformed suspicion of the face as a site of vanity gave way to a new psychological realism.

Rousseau’s Grave and the Aesthetics of Sentiment

Rousseau died in 1778 and was buried not in Geneva, but in Ermenonville, near Paris. Yet his absence loomed over his birthplace like a second presence. Throughout the 19th century, Genevans debated how to honor—or even whether to honor—him. For many, he remained a traitor to civic unity and religious discipline. For others, he was a martyr of modern freedom.

The tension culminated in the visual culture of mourning and memory. Rousseau’s writings inspired not just paintings but decorative arts, illustrations, engravings, and even porcelain. The Confessions were published with delicate vignettes of his imagined youth. His cottage at Montmorency was sketched and etched endlessly. The scene of Rousseau composing music in solitude became a favored motif—half-sentimental, half-iconic.

One particularly telling object is a locket, preserved in a Genevan collection, containing a miniature portrait of Rousseau on one side and a pressed alpine flower on the other. It is the Romantic ideal distilled: nature and person, emotion and symbol, fused in an object designed for intimate remembrance.

The Romantic style also reached into funerary art. Tombstones in Geneva’s Protestant cemeteries began to adopt softer curves, lyrical inscriptions, and even carved images of weeping willows—once forbidden as Catholic affectation. Nature was no longer suspect. It was now the language of mourning, the sanctioned expression of feeling.

This shift marked the end of Geneva’s long suppression of image and emotion. Where once the artist had to encode meaning in the corner of a copperplate, now he could paint a lake at sunset and expect to be understood. The mountain and the self had become legitimate subjects of art—thanks in no small part to the man who had loved Geneva, despised it, and changed it.

Romanticism gave Geneva a new kind of vision—not ecclesiastical, not allegorical, but existential. It taught its painters to look inward through the outward, to find meaning in solitude, and to place feeling at the center of the image. If Calvin shaped the city’s architecture, Rousseau shaped its gaze. And from that gaze came a new, enduring genre: the art of restrained emotion, set against vast and indifferent beauty.

The 19th-Century Canvas: National Style and Local Identity

By the mid-19th century, Geneva’s visual culture had begun to seek something it had long resisted: public presence. For centuries, art in the city had been confined to the private, the portable, the devotional, or the symbolic. Now, in the decades following Napoleon’s defeat and Switzerland’s federal reorganization in 1848, the question arose: what does it mean to make art for a republic? And more specifically—for a Swiss republic, and a city with a famously ambivalent relationship to national sentiment?

In Geneva, this question was answered not through grand allegory or academic bombast, but through landscape, civic memory, and local tradition—a modest yet deliberate attempt to establish visual roots in a place where art had long been rootless.

The Geneva School: Diday, Calame, and the Painter-Alpinists

In the pantheon of 19th-century Swiss art, two names dominate: François Diday (1802–1877) and Alexandre Calame (1810–1864). Both men were trained in Geneva, both painted Swiss landscapes with quasi-spiritual intensity, and both helped define a visual vocabulary that was both local and exportable.

Diday, the elder of the two, was a committed regionalist. He hiked the Alps with sketchbook and oil paint, focusing on the valleys and glaciers of the Bernese Oberland, the Rhône basin, and above all, the Genevan hinterlands. His canvases are careful, sober, and deeply rooted in natural observation—but always with an eye toward the sublime, the moment when scale overwhelms the viewer. In View of Mont Blanc from Geneva, for instance, the peak is distant but commanding, its whiteness both promise and warning.

Calame, his student and rival, took these principles further. His landscapes are more dramatic, often darker, charged with atmosphere. Trees bend under storm winds, torrents cascade over jagged rock, skies break into golden tumult. If Diday painted the Alps as a citizen, Calame painted them as a pilgrim—seeking not just scenery, but meaning.

What defined both painters—and the so-called “Geneva School” that followed them—was a belief that the landscape was more than subject matter. It was a bearer of identity. In a multilingual, confederated, often fragmented country like Switzerland, the mountain, the river, and the chalet became visual shorthand for shared belonging. In Geneva, this was particularly potent. The landscape served as a link between Calvinist simplicity, Romantic feeling, and national pride—without lapsing into nationalism.

Their work also circulated widely, purchased by collectors in France, England, and Germany. Geneva’s landscape painters became ambassadors of a neutral Switzerland, presenting it not as militarized or mythic, but as serene, ordered, and awe-inspiring.

Water, Rock, and Ice: The Visual Language of the Swiss Landscape

What Geneva’s 19th-century painters developed was not just a style, but a system of natural symbols. Each element of the landscape became a kind of code, understandable to viewers across linguistic and confessional divides.

- Water signified motion, fertility, and the Protestant ethic of clarity. The Rhône and Lake Léman were painted with mirror-like surfaces, their stillness suggesting civic order and reflection.

- Rock conveyed permanence and struggle. In paintings of mountain passes or cliffside footpaths, the rock became both obstacle and foundation—a metaphor for Switzerland’s difficult political unity.

- Ice, especially in glacier scenes, served as a reminder of both natural time and human fragility. The slow movement of the glacier echoed the slow movement of history—a secular replacement for divine providence.

These motifs were not imposed. They were inherited, often unconsciously, from Geneva’s older visual logic. Just as the Calvinist iconoclasts had redirected image into emblem, so the Genevan Romantics had redirected feeling into mountain air. The 19th-century landscape painters simply extended this: encoding political ideas into topography.

Importantly, this was not state propaganda. Switzerland’s federal government was too decentralized, and Geneva too wary of authority, to turn painting into ideology. But there was a soft nationalism at work: one that used beauty to bind, rather than command.

And yet, for all its serenity, this art was not apolitical. Paintings like Diday’s Destruction of the Village of Guttannen (1853), depicting an avalanche tearing through a hamlet, resonated with contemporary anxieties about industrialization, environmental instability, and social disruption. Nature could be beautiful—but never benign.

Museums and Memory: The Musée Rath and Civic Identity

The same period saw a major institutional shift in Geneva’s relationship to art: the founding of public museums. Until the mid-19th century, Geneva had no dedicated space for visual exhibition. Art was private, ecclesiastical, or circulated through informal salons. That changed in 1826 with the opening of the Musée Rath, Switzerland’s first purpose-built museum of fine arts.

Funded by a bequest from General Simon Rath and designed in neoclassical style, the museum became both a cultural and political statement. It was modest in scale but ambitious in mission: to bring painting, sculpture, and drawing into the public eye, and to align Geneva with the European tradition of civic collecting.

Initially, the Musée Rath focused on academic history painting, portraiture, and archaeology. But by mid-century, it began acquiring works by Diday, Calame, and other local artists—effectively canonizing the Geneva School as the city’s visual legacy. More than just a gallery, the museum served as a repository of memory: a place where Geneva could see itself, both as a city and as part of the wider Swiss project.

This new public visibility of art prompted new forms of critique. Local newspapers reviewed exhibitions. Artists debated style and subject. Citizens discussed acquisitions. Art was no longer the concern of collectors or theologians—it had become a civic conversation, albeit one framed by Geneva’s enduring preference for modesty and order.

The museum’s architecture reflected this. The building’s classical symmetry, restrained ornamentation, and central rotunda suggested Enlightenment balance rather than Romantic ecstasy. Even as it housed images of storm and mountain, the space itself remained calm.

This balance—between emotional subject and rational frame—would become a defining feature of Geneva’s art institutions. And it would inform how the city negotiated modernism, political turmoil, and the temptations of cosmopolitanism in the century to come.

By the end of the 19th century, Geneva had, for the first time in its long and careful history, a public art tradition. It was modest, yes—but it was rooted, coherent, and emotionally resonant. In the hands of its painters, mountains became memory, rivers became conscience, and museums became mirrors.

This was not the high drama of Paris or the brash symbolism of Berlin. It was a quieter claim: that beauty and belonging could coexist without spectacle. That a city with no king, no court, and no saints could still find its image on canvas—and in doing so, find itself.

Revolutionaries, Reformers, and Realists

Beneath the placid surfaces of 19th-century Alpine landscapes, Geneva was roiling with change. In the decades after 1840, political agitation, urban transformation, and class conflict began to leave their imprint not only on the city’s social order, but on its images. The quiet dignity of Diday’s glaciers and Calame’s peaks no longer captured the mood. A younger generation of artists and illustrators turned their gaze away from nature’s grandeur and toward the city itself: its workers, its alleyways, its politics.

The result was a more skeptical, more engaged visual culture—realist in form, civic in function, and frequently polemical in tone. Art in Geneva entered the public fray.

Art and the City-State: 1846 and the Radical Moment

The year 1846 marked a defining political shift: the liberal revolution that brought about the Genevan Radical Republic. The conservative aristocratic regime was overthrown, and a more egalitarian, anticlerical order took its place—ushering in sweeping reforms to education, voting rights, and the organization of the public sphere.

This revolution, part of a broader Swiss political reorganization culminating in the 1848 federal constitution, had aesthetic consequences. Public buildings were renovated or constructed anew. Streets were widened, markets reorganized, and the old bastions of church power reoriented toward secular use. The artist was no longer merely an observer. He was now, occasionally, a participant—and often a critic.

Visual culture responded to this political volatility by embracing new forms of urban realism. Painters such as Barthélemy Menn, a student of Ingres and an influential figure in Geneva’s art education, began depicting the city’s workers, markets, and everyday rhythms with unsentimental directness. Menn’s palette was quiet, his touch refined, but his subject matter increasingly reflected a Geneva at work—not idealized, not tragic, but simply observed.

Menn’s drawing classes at the École des Beaux-Arts cultivated a generation of artists for whom draftsmanship, precision, and close study became not just technique, but a worldview. The student sketchbook replaced the alpine panorama. And in doing so, art reentered civic life—not through monument, but through observation.

Caricature, Satire, and Political Print

More immediate—and more volatile—was the rise of political caricature and satirical illustration, especially in the form of lithographed pamphlets, newspapers, and posters. Geneva’s robust print infrastructure, already central to Protestant publishing and scientific literature, proved ideal for visual polemic. And in the revolutionary decades of the mid-19th century, satire became a dominant aesthetic form.

Geneva had long used allegory to communicate moral ideals. Now, it used it to mock authority, expose hypocrisy, and provoke debate. Artists like Édouard Castres, who later became known for his panoramic war scenes, began their careers sketching street life, soldiering, and scenes of civil unrest with loose, dynamic lines and unromantic realism.

Pamphlets from the 1840s and ’50s featured cartoon bishops with swollen bellies, militiamen asleep on duty, and parliamentarians with donkey ears. These were not mass-market distractions. They were visual arguments, widely distributed in cafés, reading rooms, and public squares. The lithographic press allowed for quick production and circulation; a well-executed caricature could be as influential as a sermon.

The visual style of these prints drew from both French satirical traditions (notably Daumier) and German political engraving, but adapted to Geneva’s more cerebral, less theatrical temperament. The line was sharp, the humor dry. And though the subjects were local, the underlying issues—censorship, corruption, reform—echoed across Europe.

By the 1860s, Geneva’s political illustrators had carved out a unique position: not state-sponsored artists, nor commercial entertainers, but civic watchdogs with pencils and stones.

The Industrial City and the Artist’s Response

Geneva, while never a manufacturing metropolis, did experience rapid industrial and demographic changes in the latter half of the 19th century. The expansion of the watch industry, the development of mechanical trades, and the arrival of new working-class neighborhoods reshaped the city’s structure—and its image.

Artists began to respond. The factories along the Rhône, the crowded streets of Saint-Gervais, the dockworkers at Port Noir—these became subjects of painting and printmaking. Not in grand style, but with documentary precision.

The emerging Genevan realism often depicted:

- The laboring body: not heroic, not degraded, simply present. Workers sharpening tools, porters hauling barrels, seamstresses at low tables.

- The built environment: bridges under construction, chimneys in fog, railway tracks stretching into darkness.

- The crowd: processions, protests, funerals—not as symbols, but as social facts.

In these works, Geneva ceased to be a moral emblem or sublime vantage. It became a city among cities—material, complex, and unsettled. This realism, while never dominant, created a countercurrent within Geneva’s art world: one that challenged the decorative, ignored the mythic, and insisted on the visibility of labor.

At the same time, the city’s public institutions—especially the Musée Rath—struggled with this shift. The museum had been built for history paintings, landscapes, and academic sculpture. It had little appetite for social realism. As a result, much of this work circulated outside official channels—in journals, private collections, or short-lived exhibitions.

Even so, the tension between public respectability and private critique became part of Geneva’s visual identity. Artists walked a line between civic loyalty and social commentary, a balancing act that would only intensify with the advent of modernism.

The second half of the 19th century brought Geneva’s artists into closer contact with power, contradiction, and daily life. The Reformed city, once suspicious of image, now hosted a visual culture that was satirical, observational, and politically alert. It did not glorify revolution, but it depicted its aftermath. It did not celebrate the working class, but it recorded its presence. And it began to treat the city itself—not just its mountains or its saints—as worthy of artistic scrutiny.

Realism in Geneva was never an ideology. It was a stance: to look, carefully and without euphemism, at what was actually there. And in doing so, it extended the city’s long tradition of moral clarity into the murky light of modern politics.

Geneva in the Age of Modernism

Geneva entered the 20th century with a quiet skepticism toward modernism. Unlike Zurich, which embraced avant-garde provocation in the form of Dada, or Paris, which seethed with Cubist, Fauvist, and Surrealist innovation, Geneva seemed insulated—by Calvinist reserve, by the memory of its bourgeois century, and by a cultural machinery still oriented around academic painting, landscape art, and decorative refinement.

And yet modernism came. It arrived through architects, émigré artists, exiled intellectuals, and returning sons. In Geneva, modernism did not explode. It diffused. It adapted to local rhythms. What emerged was a measured modernism—geometrical rather than ecstatic, rational rather than violent, shaped as much by international currents as by Geneva’s own instincts for discipline and understatement.

Le Corbusier, Jeanneret, and the Architecture of the Future

The most influential modernist to emerge from Geneva’s broader orbit was born just beyond its borders: Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier. Though he made his name in Paris, Le Corbusier received his early education and artistic formation in the Swiss Romandy, and his visual language—clear lines, austere volumes, a belief in structural order—can be traced in part to the Protestant and topographic conditions of his youth.

In Geneva itself, Le Corbusier’s physical legacy is modest. He never reshaped the city the way Haussmann had reshaped Paris or Wagner had reshaped Vienna. But his ideas circulated widely. The Geneva headquarters of the League of Nations, built in the interwar years, reflected many of the same impulses: symmetry, clarity, minimalism, rational use of space. Though the complex was not designed by Le Corbusier, the architectural culture of Geneva—especially among municipal planners—was deeply shaped by his vision of modernity as order through abstraction.

His cousin and occasional collaborator, Pierre Jeanneret, also contributed to this vision, designing furniture, interiors, and public housing concepts that reflected a Genevan ethos: utility before ornament, structure before gesture.

The architectural modernism that took root in Geneva was not utopian or ideological. It was administrative, almost bureaucratic in tone. But it brought with it a quiet visual revolution:

- Government offices and public housing adopted modular forms, clean facades, and minimal signage.

- Urban infrastructure—tram stations, bridges, libraries—began to reflect the aesthetics of efficiency.

- New schools of design and planning emerged, with curricula that emphasized functional beauty, in harmony with Geneva’s historic aversion to excess.

This architecture did not seek to shock. It sought to clarify. In that, it found local success.

Kandinsky, Jawlensky, and the Saint-Prex Circle

If Geneva’s architects embraced modernism through calculation, its painters absorbed it through migration and encounter. The city’s neutrality in both World Wars made it a haven for artists, many of them fleeing Central Europe. Some passed through. Others stayed. Among them were members of the Der Blaue Reiter and Bauhaus circles, as well as Russian émigrés and German modernists seeking respite from totalitarianism.

One particularly influential node was the Saint-Prex Circle, a loose network of artists and intellectuals centered around the lakeside village of Saint-Prex, just outside Geneva. There, in the interwar years, Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, and others gathered to paint, teach, and debate. Their presence brought abstraction into Geneva’s visual vocabulary—not as ideology, but as spiritual experiment.

Kandinsky’s theory of the spiritual in art—his belief that color and form could evoke inner states independent of representation—resonated with Geneva’s long-standing suspicion of visual seduction. Here was abstraction not as play, but as principle. A theology of the square, the line, the hue.

Jawlensky, who spent years in Switzerland, brought a more expressive approach. His Abstract Heads series—stylized portraits reduced to bold contours and pure color—suggested a bridge between icon and intuition. Geneva, once a city of iconoclasts, now hosted icons of interiority.

Though most of these artists were not native Genevans, they shaped the city’s galleries, collectors, and younger artists. Their exhibitions at the Musée Rath and other venues introduced Genevan audiences to:

- Non-representational form, not as a rejection of tradition, but as an extension of it.

- Color as emotion, particularly in response to a cultural climate dominated by verbal logic and textuality.

- The image as meditation, in harmony with Geneva’s enduring preference for reflection over assertion.

What Geneva absorbed from these artists was not their rebellion, but their discipline—a common ground that allowed even radical forms to take root in a reserved city.

Abstraction in a Neutral Zone: Wartime and the Avant-Garde

The World Wars reshaped Geneva, not through bombs or battle lines, but through displacement, surveillance, and silence. As home to the League of Nations and, later, the United Nations Office, the city became a center for diplomacy, espionage, and humanitarian bureaucracy. This tension—between neutrality and conflict—had a visual echo.

Art in Geneva during the wars often took the form of coded abstraction. Figurative painting declined. Symbolism returned—but stripped of allegory. In its place came textures, rhythms, materials. Artists experimented with:

- Collage, using newspaper fragments, ration cards, and bureaucratic forms.

- Concrete art, in the tradition of Max Bill and the Swiss Constructivists, which emphasized geometric purity and universal language.

- Silent surfaces, where blankness, repetition, and restraint suggested trauma without narrative.

One emblematic figure was Sophie Taeuber-Arp, the Swiss painter, textile artist, and dancer who spent time in Geneva during the 1940s. Though better associated with Zurich and the Dada movement, Taeuber-Arp’s formal clarity and rhythmic abstraction found sympathetic audiences in Geneva. Her work—with its precise grids, stitched textiles, and painted geometries—embodied a reimagining of ornament as thought.

What Geneva offered the modernists was not community or manifesto. It offered silence—a place to work, to survive, and to smuggle art through the cracks of ideology.

This dynamic persisted after the war. Geneva’s postwar exhibitions often lagged behind Paris or Milan in terms of shock value, but they introduced abstract formalism, conceptual clarity, and cross-disciplinary dialogue. Artists worked quietly, rigorously, often without acclaim.

For Geneva, modernism never meant rupture. It meant recalibration. In this city, the avant-garde was less a scream than a measured step sideways.

Modernism came to Geneva not with the violence of revolution, but with the insistence of a long argument: between history and innovation, clarity and chaos, image and idea. It reshaped the city’s architecture, informed its design culture, and gave its painters permission to abandon the visible world—not in rebellion, but in search of new forms of meaning.

Geneva’s modernism is often overlooked for lack of spectacle. But in its restraint lies its signature: a belief that form, when honed and disciplined, can still speak with force.

Biennials, Banks, and the Art of Discretion: Postwar Collecting and Display

By the middle of the 20th century, Geneva had become a paradox: a small city with global reach, a Protestant stronghold turned financial hub, a capital of diplomacy more than politics, and a home to wealth that preferred not to be seen. Its art world reflected this contradiction. There were no blockbuster institutions to rival Paris or New York, no nationalist commissions, no ideological public art drives. Yet Geneva became one of the most significant centers of postwar collecting, exhibition, and private display in Europe.

It was not a center of production. It was a city of reception—of exhibitions carefully curated, collections quietly amassed, and artworks moved discreetly between vaults, apartments, foundations, and airport terminals. Art in postwar Geneva became part of a new visual economy: embedded in private capital, shaped by global finance, and almost always tempered by discretion.

The Rise of the Private Collector and the Tax Haven Gallery

In the postwar decades, Geneva attracted not only diplomats and watchmakers, but private wealth from across the globe. Banking secrecy laws, favorable tax regimes, and political neutrality made the city a preferred residence (or fiscal address) for clients from Latin America, the Middle East, and postcolonial Africa. Alongside this financial influx came a new kind of art patron: the private international collector.

These collectors—some discreet, others notorious—did not necessarily engage with local art scenes. They worked through advisors, dealers, and law firms, often based in or near the Rues Basses and Quartier des Banques. Artworks were stored in freeports, displayed in villas, or used as collateral in complex financial arrangements. The art object, in Geneva, was often more asset than aesthetic.

Yet the collecting was real, and in many cases rigorous. Geneva became home to one of the world’s highest densities of major 20th-century artworks per capita—Picassos, Rothkos, Fontanas, Giacomettis—all rarely visible, all privately held. This prompted a culture of quiet excellence, visible in three ways:

- Discreet showrooms and salons, often hidden behind unmarked doors, where dealers exhibited museum-quality works to a handful of trusted clients.

- Boutique foundations, often registered under obscure names, which lent major pieces to foreign exhibitions while keeping the collector’s identity concealed.

- Art banks, offering services like valuation, authentication, and secure storage—not as cultural services, but as financial instruments.

This collecting culture reshaped Geneva’s relationship to art. The museum was no longer the primary institution of visibility. Instead, visibility became optional. Prestige came not from public recognition, but from curatorial authority, provenance management, and discretion.

Art in Geneva, once suspect for its allure, was now embraced—but carefully. Very carefully.

Kunsthalle Geneva and the Performance Turn

Despite this elite enclosure, Geneva also cultivated a parallel, more open strand of contemporary art practice—centered around experimental institutions, performance spaces, and artist-run venues. Chief among them was the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, often referred to as the Kunsthalle Geneva, founded in 1974. Modeled loosely on German non-collecting institutions, it became a laboratory for conceptual art, video installation, and performance.

The Kunsthalle’s early programming reflected a determination to avoid Geneva’s conservatism. Artists such as Dan Graham, Valie Export, and Christian Boltanski showed works that challenged the neutrality of space, the mechanics of spectatorship, and the politics of memory. Exhibitions were small, but ideas were large. There was little money, but considerable influence.

Geneva’s artists, though few in number, responded to this climate with rigor. Local figures like Sylvie Fleury, known for her critical engagement with consumer culture, and John Armleder, co-founder of the Ecart Group, bridged Swiss conceptualism and international postmodern aesthetics. Their work played directly into Geneva’s tensions—between surface and substance, between luxury and critique.

Armleder’s practice, in particular, embodied Geneva’s double art life: formalism with a wink, high finish with ironic detachment. His installations—featuring poured paint, mirrored surfaces, and designed objects—spoke to a city where ornament had returned, but only conditionally.

By the 1980s and ’90s, a recognizable Genevan aesthetic had emerged within the European contemporary art circuit:

- Cool surfaces: chrome, glass, and monochrome dominated.

- Institutional critique: many works commented on the art system itself, reflecting Geneva’s networked art-finance landscape.

- Conceptual restraint: ideas remained central, but were executed with Geneva’s characteristic understatement.

Geneva did not become a scene. But it became an axis—a place where ideas passed through, where artists tested limits, and where work that might seem provocatively minimal elsewhere found natural footing.

UN Art, Diplomatic Gifts, and the Global Image Economy

One of the more unusual aspects of Geneva’s art world—often overlooked in surveys—is its role as a hub of diplomatic art exchange. As host to the United Nations Office at Geneva and numerous NGOs, the city became a receptacle for state-sponsored artworks, commemorative gifts, and symbolic installations.

The Palais des Nations houses an eclectic array: sculptures from African nations, tapestries from Eastern Europe, lacquer screens from East Asia, and mural-sized paintings gifted by various states. These works, though rarely discussed in art historical terms, represent a parallel canon: art made to express goodwill, national identity, or ideological affiliation.

This is art not for critique, but for containment—placed in corridors, foyers, and meeting rooms, each object carefully calibrated to offend no one, honor everyone, and symbolize peace. It is the visual language of diplomacy, and Geneva became its archive.

At the same time, Geneva’s position in the global image economy expanded. International auctions, blue-chip gallery fairs, and art law firms treated the city as a node in a transnational web—connecting London, Dubai, New York, and Hong Kong. The art object as negotiable instrument became an accepted category, and Geneva’s freeports—vast, climate-controlled, and opaque—housed billions of francs in paintings, many never seen.

This has led to periodic controversy. Journalists have investigated the use of art for tax avoidance, the storage of looted or disputed works, and the ethical limits of art-as-asset. Geneva’s institutions have largely remained silent, preferring caution over confrontation. Yet the facts are plain: Geneva is one of the world’s most important cities for art that is owned but not shown.

And this too is a kind of aesthetic position—one deeply Genevan.

Postwar Geneva embraced the visual world it had once resisted—but on its own terms. It opened galleries, collected globally, funded foundations, hosted biennials. Yet it did so with a caution shaped by centuries of theological suspicion, civic modesty, and economic pragmatism.

The result is a city where art is everywhere and nowhere—housed in vaults, whispered in salons, theorized in institutions, and rarely declared. In Geneva, art became not spectacle, not sermon, not ideology—but a question of access.

Contemporary Geneva: Transnational Aesthetics in a Fragmented City