Tucked away in the stone halls of The Cloisters Museum in New York, a series of seven tapestries have mystified scholars, historians, and art lovers for centuries. Known collectively as The Unicorn Tapestries, these late medieval works are among the most intricate and symbolic textiles ever created in Europe. They depict a dramatic and richly layered tale of a unicorn hunt, blending elements of courtly romance, religious allegory, and naturalistic beauty. Despite their prominence, their exact origins—who designed them, for what purpose, and with what message—remain unresolved.

The Unicorn Tapestries are believed to have been created around 1495 to 1505 AD, a time when Northern Europe was flourishing with trade, faith, and art. Their craftsmanship, complex symbolism, and detailed portrayal of flora and fauna place them among the finest examples of medieval textile work. Today, they are housed at The Cloisters, a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they continue to draw both art historians and curious tourists alike. Their presence has become a visual centerpiece in any discussion of medieval imagination and craftsmanship.

What makes these tapestries so unusual is not merely their age or beauty, but the tension between their realism and their mythology. On one hand, we see painstaking detail: trees with identifiable species, animals that could be sketched from life, and faces filled with emotion. On the other, we are drawn into a world where unicorns—mythical creatures—are treated as real, hunted by noblemen, and ultimately caged like a beast or revered like a savior. This ambiguity is part of their enduring appeal.

Visitors who view the Unicorn Tapestries today often ask the same questions that art historians have pondered for decades. Who created them? Why was the unicorn so significant? Are these scenes meant to be religious, romantic, or political? The journey to answer these questions takes us deep into the world of late medieval Europe—where belief, beauty, and storytelling wove together on the loom just as tightly as silk and wool.

Where They Are Today – The Cloisters Museum

The Unicorn Tapestries are displayed in a climate-controlled, stone-walled gallery at The Met Cloisters, located in Fort Tryon Park in northern Manhattan. This museum is dedicated exclusively to medieval European art and architecture, built in the 1930s with parts of actual medieval buildings imported from France and Spain. It was funded and assembled by John D. Rockefeller Jr., who also donated the tapestries to the museum after purchasing them in the 1920s.

The decision to place the Unicorn Tapestries in The Cloisters was not accidental. The museum was designed to recreate the spiritual atmosphere of medieval monastic life, and the tapestries—rich in symbolism and silent reverence—fit that mission perfectly. Inside the gallery, they are hung to mimic their original function as wall hangings in a grand noble residence or chapel, giving viewers a chance to experience them as their original audience might have.

Conservators at The Met have taken great care to preserve the Unicorn Tapestries, using minimal lighting and careful temperature controls. Because of their age and delicate materials—including silk, wool, and metallic threads—they are susceptible to fading and deterioration. The meticulous work of preserving these tapestries is a tribute to the enduring value of Western artistic heritage.

Their placement at The Cloisters has also made them a popular destination for scholars and art lovers from around the world. Whether one comes for the religious symbolism, the historical mystery, or simply the stunning visual detail, the Unicorn Tapestries offer a profound encounter with the medieval world—and a reminder of the power of visual storytelling before the printing press made books common.

What Are the Unicorn Tapestries?

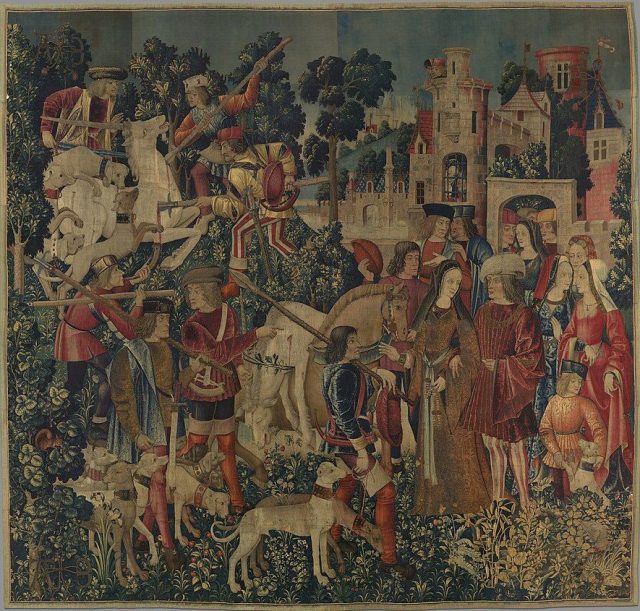

The Unicorn Tapestries are a set of seven individual panels, commonly referred to as The Hunt of the Unicorn. They were likely woven in the Southern Netherlands, possibly Brussels or Bruges, in the last years of the 15th century or very early in the 16th. These tapestries are large—some over 12 feet wide and more than 10 feet high—and filled with thousands of intricate details.

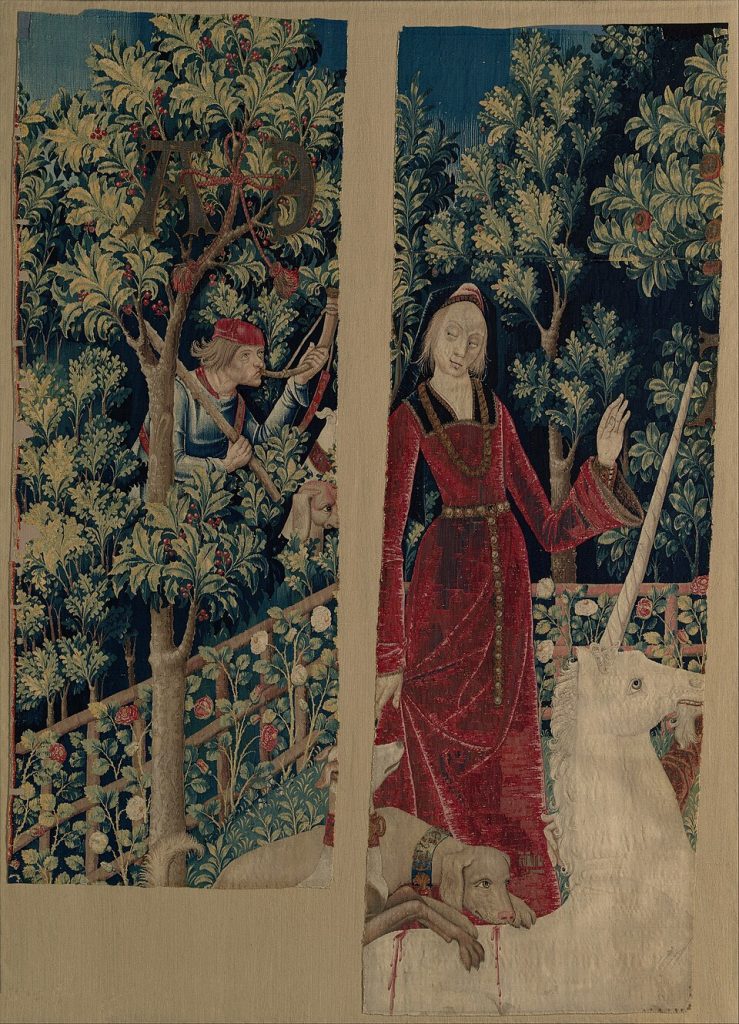

The scenes appear to tell a continuous story, beginning with noblemen setting out on a unicorn hunt and ending with the unicorn alive but chained within a small garden enclosure. Each panel includes hunters, dogs, a richly decorated landscape, and the central figure of the unicorn. The identity of the artist remains unknown, though scholars agree that the design, known as a cartoon, was likely made by a professional painter, then handed to a team of master weavers.

Scholars believe the tapestries were created for a wealthy noble patron, most likely connected to French aristocracy. Some panels contain a pair of initials—AE—but their meaning is still debated. The tapestries also feature heraldic devices believed to be associated with the La Rochefoucauld family, a powerful French lineage with lands in central France.

The combination of religious allegory, romantic symbolism, and natural beauty gives the Unicorn Tapestries a layered richness rare even among great works of European art. Whether viewed as theological parables, moral lessons, or political statements, these panels invite continual contemplation—and very few definitive answers.

Origins and Attribution: Who Wove This Tale?

The origin of the Unicorn Tapestries remains one of their central enigmas. Scholars have proposed various theories based on style, technique, and heraldry, but no single narrative has emerged with absolute certainty. Most agree that the tapestries were likely designed in Paris and woven in a major Flemish city such as Brussels or Bruges, which were known centers of tapestry production during the late 15th century.

At the time, Flanders was one of the wealthiest and most culturally advanced regions in Europe. It operated under the Burgundian court and later under the Habsburgs, both of whom were major patrons of the arts. Tapestries were a prime status symbol, more expensive and prestigious than paintings. A single panel could take a team of weavers more than a year to complete, and entire sets often took several years to finish. This scale of labor and cost points to a patron of considerable means and importance.

The tapestries bear no known artist’s signature. This was typical in tapestry production, where a division of labor meant that the cartoon designer, the master weaver, and the workshop as a whole all contributed to the final product. This anonymity adds to the mystery, though art historians have suggested that the artist may have been influenced by or directly related to the school of Jean Bourdichon or other illuminators working in France in the late 1400s.

The most tangible clue about the patron lies in the heraldic devices displayed in several panels. These arms have been linked to the La Rochefoucauld family, a noble line with roots going back to the time of Charlemagne. This family lived at Château de Verteuil, where the tapestries were rediscovered in the 19th century. While not definitive, the presence of the arms strongly suggests that the family commissioned or at least came into possession of the tapestries not long after their creation.

The Workshop Tradition of Flanders

Flemish tapestry workshops were among the most advanced in Europe by 1500 AD. Cities like Brussels, Tournai, and Bruges had guild systems that enforced strict quality standards. Workshops typically worked from detailed painted cartoons that acted as full-scale blueprints for the weavers. The designer was usually a trained painter, and the weavers were highly skilled artisans, often working on looms that could accommodate large wall-sized pieces.

Materials included fine wool and silk, often dyed with costly imported pigments like cochineal red or indigo blue. Some tapestries, including parts of the Unicorn series, also used threads wrapped in silver or gold, making them even more luxurious. The effort required to produce a tapestry of this size and complexity would have involved years of labor and substantial financial investment.

Brussels held a special reputation for religious and allegorical tapestries. Many high-ranking nobles, including the Habsburgs and the Valois Dukes of Burgundy, ordered their finest works from these workshops. This makes it plausible that the Unicorn Tapestries were woven in such an environment—rich in talent, steeped in tradition, and deeply tied to European court culture.

Possible Patrons and Families

The presence of a distinctive monogram and heraldry has drawn attention to the La Rochefoucauld family as probable patrons. In particular, the inclusion of two specific coats of arms—seen in four of the tapestries—links the pieces to this noble lineage. This family played a significant role in French history, maintaining loyalty to the Crown during conflicts like the Hundred Years’ War and the Wars of Religion.

The La Rochefoucauld residence, Château de Verteuil, where the tapestries were discovered in the 1800s, further supports the connection. Some scholars believe the tapestries may have been part of a marriage dowry or commissioned to commemorate a significant event such as an alliance or birth. If so, this would explain the blending of Christian, romantic, and political symbolism throughout the series.

There is also speculation that the AE monogram seen in the tapestries may refer to Antoine de La Rochefoucauld and his wife, Antoinette d’Amboise, who married in the late 15th century. While this theory remains unconfirmed, it fits the known timelines and the cultural practice of using art to mark noble marriages or dynastic continuity.

Narrative in Thread: What the Tapestries Depict

The Unicorn Tapestries unfold a visually stunning and symbolically complex narrative across seven individual panels. Together, they are widely interpreted as telling the story of a unicorn being hunted, captured, slain, and resurrected or tamed. While scholars debate whether the sequence is strictly linear or more allegorical in nature, each panel contributes to a tapestry of meaning that ranges from theological symbolism to noble virtue and romantic conquest. The order of the panels is not definitively known, but most modern displays follow a generally accepted narrative arc based on thematic progression and visual cues.

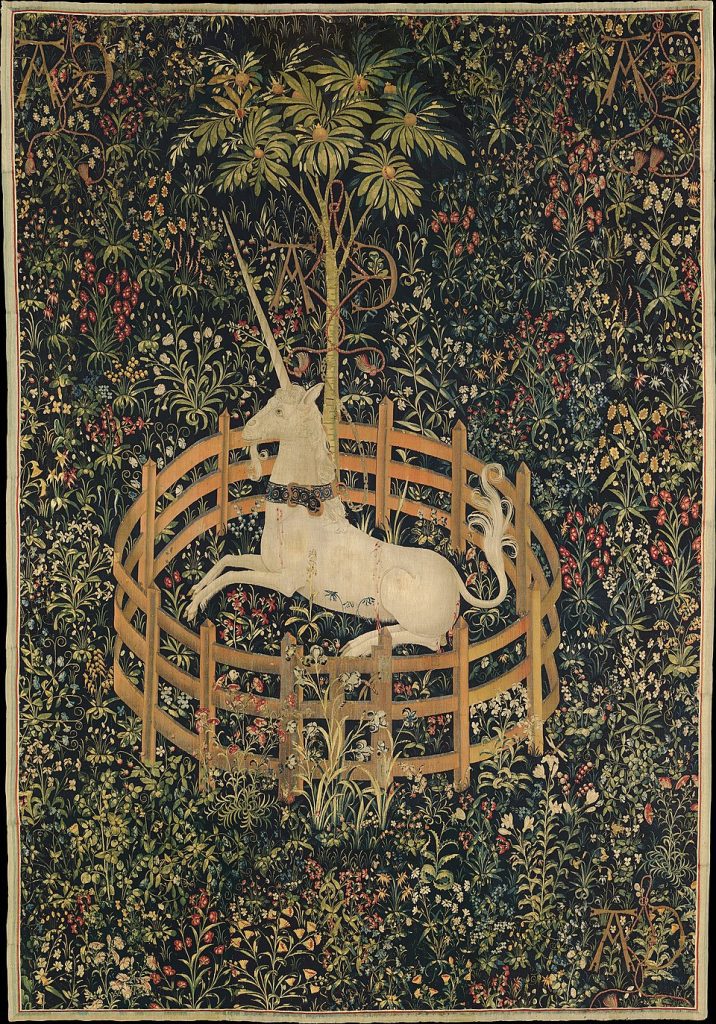

The story begins with a group of noblemen preparing for a unicorn hunt, aided by hunting dogs and servants. The unicorn appears in a forest setting, surrounded by rich foliage and an array of animals. As the hunt progresses, the unicorn is chased, cornered, wounded, and finally captured. However, in the final panel—“The Unicorn in Captivity”—the creature appears very much alive, calmly seated within a fenced garden, bound by a golden chain to a tree, but seemingly unharmed. This final image introduces a dramatic shift in tone, suggesting redemption, rebirth, or even willing submission.

One reason for the tapestries’ enduring fascination is their combination of naturalistic detail with mythic content. More than 100 identifiable plant species fill the backgrounds, many of them with known symbolic meanings in Christian or folk traditions. The clothing, weapons, and dogs are rendered with exceptional realism, providing an authentic glimpse into late 15th-century noble life. Yet at the center of every panel is the unicorn—a creature that no viewer has ever seen in real life, but whose presence is treated as entirely believable within the world of the tapestries.

Whether intended as a love story, an allegory of Christ, or a political metaphor, the narrative remains open to interpretation. The lack of written text, combined with the ambiguity of the scenes, invites the viewer to participate in the story by supplying their own meaning. That quality—an open-ended invitation to wonder—may be one of the reasons the Unicorn Tapestries continue to resonate so powerfully across the centuries.

Key Scenes in the Series

Each of the seven panels in the Unicorn Tapestries presents a distinct but interrelated moment in the story. Though there is some debate over the original sequence, most scholars and curators follow this commonly accepted arrangement:

Bullet List: The Seven Panels of the Unicorn Tapestries

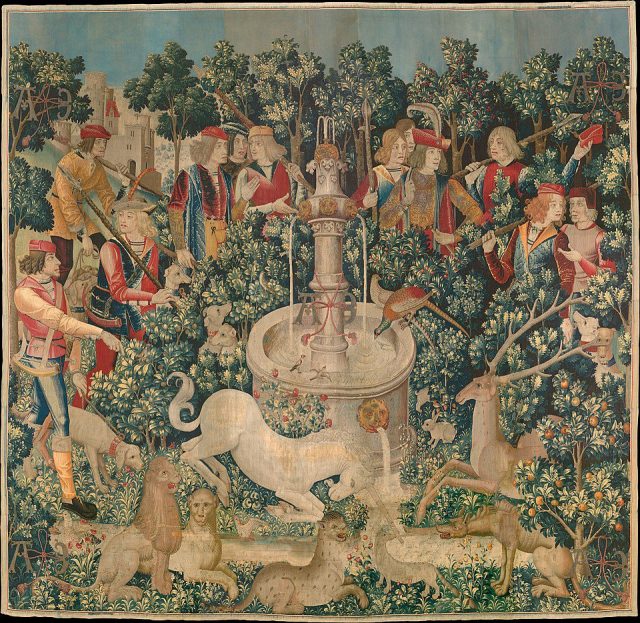

- “The Start of the Hunt” – A group of noblemen and servants prepare for the hunt in a richly wooded landscape. Horns are sounded, hounds are unleashed, and the tone is set for pursuit.

- “The Unicorn Leaps into the Stream” – The unicorn is first sighted, its body in mid-leap as it tries to escape into a flowing stream, pursued closely by hunting dogs.

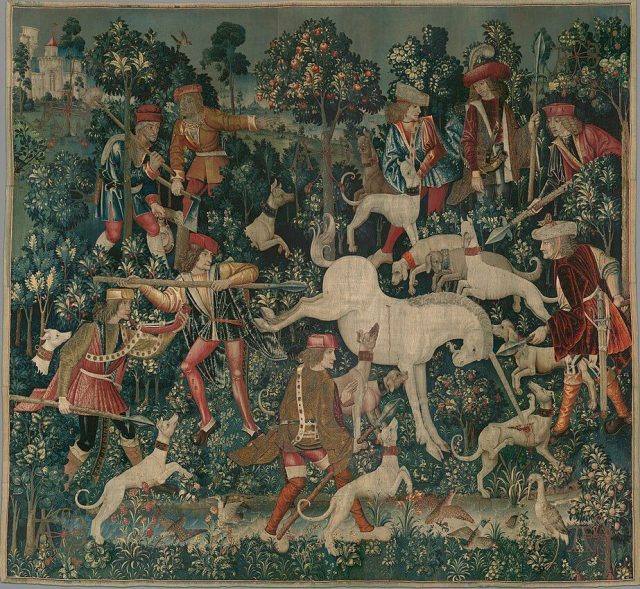

- “The Unicorn Crosses the Stream” – The hunters attempt to catch the unicorn as it moves deeper into the forest. There is tension between the spiritual calm of the unicorn and the violence of its pursuers.

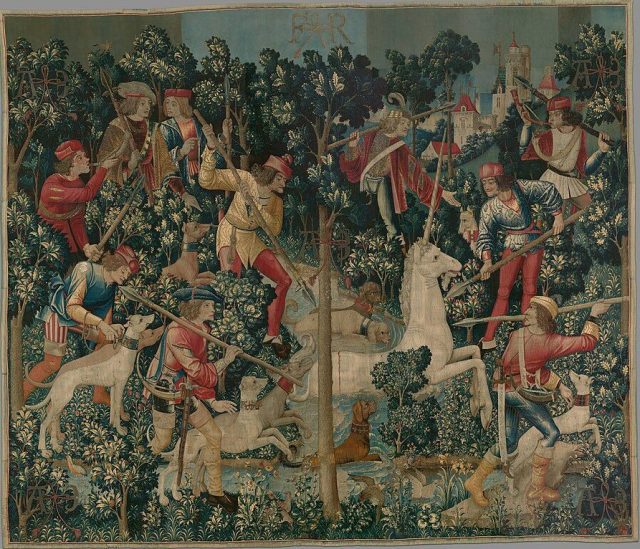

- “The Unicorn Defends Itself” – The unicorn fights back fiercely against the hunters and dogs, goring at least one hound with its horn. Blood begins to appear in the scene.

- “The Unicorn is Killed and Brought to the Castle” – In a dramatic panel, the unicorn lies slain, surrounded by mourning figures and bleeding profusely. The body is loaded onto a cart and carried toward a castle.

- “The Unicorn is Resurrected” – In some interpretations, this panel suggests a miraculous rebirth or transformation, with the unicorn appearing once again in a more peaceful setting.

- “The Unicorn in Captivity” – The final and most famous image shows the unicorn alive, bound by a gold chain within a circular fenced garden, surrounded by flowers and pomegranates.

The “Unicorn in Captivity” Panel

The last tapestry in the series, “The Unicorn in Captivity,” has drawn more attention and interpretation than any of the others. Here, the unicorn stands out clearly from its surrounding narrative. It appears unhurt, despite having previously been hunted and slain. Its posture is calm, and its expression almost serene, as it sits tethered to a small tree inside a fenced enclosure. Blood appears absent, and the sense of violence from the earlier scenes has been replaced with peace, even delight.

Symbolically, this image has been linked to everything from the Resurrection of Christ to the fulfillment of romantic love. The unicorn’s chain is not tight, suggesting it remains by choice, not force. The garden—often interpreted as a symbol of paradise or virginity—is overflowing with blooming flowers, pomegranates, and ripe fruit, all of which had significant meanings in medieval Christian and classical traditions. The pomegranate, in particular, symbolized fertility, resurrection, and eternal life.

Some scholars believe this panel represents the final taming of the unicorn by a virgin, a common allegory for the soul’s acceptance of divine truth or Christ’s incarnation through Mary. Others argue that it signifies the triumph of courtly love, with the unicorn subdued by beauty and gentleness rather than violence. Still others suggest a political meaning: the unicorn as a conquered but still noble creature, symbolizing the subjugation of a powerful enemy or rival house.

Whatever the interpretation, the Unicorn in Captivity stands alone as one of the most memorable and enigmatic images in all of medieval art. It challenges the viewer to reconcile the apparent contradictions—freedom and bondage, death and life, power and submission—into a unified vision of meaning. It also serves as a fitting end to a series that refuses easy answers, rewarding those who look deeper.

Symbolism and Allegory: Christian, Pagan, or Personal?

The Unicorn Tapestries are far more than a record of a mythical hunt; they are steeped in symbolism drawn from Christian doctrine, medieval bestiaries, courtly traditions, and possibly even personal heraldic meanings. In the Middle Ages, every object, creature, and flower could carry a layered significance, especially in works intended for aristocratic or religious spaces. The unicorn, in particular, was one of the most symbolically loaded creatures in medieval lore. Depending on the context, it could represent Christ, purity, immortality, or the noble spirit.

In Christian symbolism, the unicorn was most commonly associated with the Incarnation of Christ. This idea stems from medieval bestiaries and earlier sources like the Physiologus, a Christian allegorical text from around the 2nd century AD that remained widely read throughout the Middle Ages. According to the bestiary tradition, the unicorn could only be tamed by a virgin maiden—once it laid its head in her lap, it became docile and could be captured or even slain. Medieval theologians interpreted this tale as a metaphor for Christ entering the womb of the Virgin Mary. The unicorn’s death in the hunt represented Christ’s Passion, and its later revival symbolized the Resurrection.

Yet not all interpretations are strictly religious. The imagery also lends itself to the world of chivalric romance and aristocratic love. Many scholars have suggested that the unicorn could represent a lover—pure, powerful, and elusive—who is finally “captured” by a woman. This aligns with medieval courtly love literature, in which the pursuit of the beloved was often framed as a noble and dangerous quest. From this perspective, the hunt is not a religious allegory but a symbolic pursuit of romantic conquest.

There’s also the possibility of deeply personal symbolism embedded within the work, specific to the patron who commissioned it. The use of heraldic devices points to family pride and dynastic power. In this reading, the unicorn may represent a particular family virtue—loyalty, courage, or chastity—that has been won and preserved through struggle. The ambiguity of the tapestries allows all these meanings to coexist, making them a canvas onto which many generations have projected their own understandings.

Christian Allegory and Virgin Imagery

The most widely accepted symbolic reading of the Unicorn Tapestries is rooted in Christian theology. In this interpretation, the unicorn is a symbol of Christ, the divine made flesh. The virgin who tames the unicorn represents the Virgin Mary, whose purity allows her to “capture” divinity within her womb. This imagery was deeply familiar to medieval audiences and appears in many other works of art and literature from the period.

When the unicorn is hunted, wounded, and killed, the scenes mirror the Passion of Christ—His betrayal, suffering, and crucifixion. The fact that the unicorn is eventually resurrected or shown alive again in the final panel reinforces the connection to the Resurrection. This theological framework would have made sense to a medieval noble patron, who lived in a society where religious instruction was visual as well as verbal, and where private chapels often featured religious tapestries.

Supporting this view is the inclusion of symbolic flora and fauna throughout the series. The dog, traditionally associated with loyalty, may represent the faithful. The lambs could stand for the flock of Christ. Flowers like the lily and iris point to purity and resurrection. The presence of a fountain in one of the panels recalls baptism, which itself symbolizes the death and rebirth of the soul.

This Christian allegory does not exclude other meanings but offers a dominant framework through which the tapestries were likely understood at the time of their creation. In an era when art was meant to instruct and inspire, embedding moral or doctrinal meaning within beauty was not merely encouraged—it was expected.

Secular and Courtly Interpretations

Beyond theology, the tapestries also resonate with the language of courtly love and secular chivalric values. In this reading, the unicorn becomes the ultimate symbol of desire—pure, noble, and unattainable. The hunt for the unicorn mirrors the aristocratic pursuit of a beloved lady, often portrayed in medieval poetry as a quest that demanded both bravery and humility. Capture is not mere conquest; it is the reward for devotion and constancy.

The presence of richly dressed nobles, musicians, and a sense of pageantry throughout the tapestries supports this interpretation. These are not common hunters but members of a sophisticated court, engaged in a stylized and symbolic activity. The chain that binds the unicorn in the final panel may be seen not as imprisonment but as willing surrender—a creature who submits to love and fidelity rather than brute force.

Marriage symbolism is also present. The tapestries may have been commissioned as a wedding gift, with the unicorn representing the groom’s virtues and the hunt symbolizing the bride’s acceptance of him. The circular fence enclosing the unicorn in the final scene could represent marital fidelity or the enclosed garden (hortus conclusus) often associated with virginity and female purity.

Such readings reflect the values of a courtly elite steeped in both romantic ideals and a strong sense of lineage. Whether intended as a religious parable or a symbolic love story, the tapestries speak to the highest aspirations of the noble class—purity, courage, self-sacrifice, and the enduring bond between man and woman.

Artistry and Technique: Weaving the Mystical

Beyond their symbolism and narrative, the Unicorn Tapestries are masterpieces of late medieval craftsmanship. The level of detail, the range of colors, and the use of costly materials make these works stand among the finest tapestries ever produced in Europe. Created in the period between 1495 and 1505 AD, they exemplify the technical sophistication of Flemish weaving workshops, which dominated European textile production during the 15th and early 16th centuries. These tapestries were more than decorative; they were luxury items that signaled the patron’s wealth, piety, and cultural refinement.

Each tapestry in the series was woven with a mix of wool and silk, with some metallic threads used to highlight details. The silk added sheen and softness, while wool provided durability and color saturation. The artists responsible for the “cartoons”—the full-scale drawings used to guide the weavers—were likely trained painters. Their influence is evident in the tapestries’ sophisticated use of perspective, modeling, and proportion, which bring a painterly realism to the textile medium. Even the light and shadow seem carefully rendered, despite the limitations of thread and loom.

The creation of such works involved a tremendous labor force. A single tapestry could take more than a year to produce, depending on size and complexity. Multiple weavers would work side by side on large horizontal looms, building the image from the bottom upward. These artisans often worked from behind the tapestry, meaning the finished image was a mirror of what they saw during weaving. Only the most skilled and experienced workers could maintain visual consistency across large, intricate works like these.

Artistry in the Unicorn Tapestries is not limited to figures and scenery. The backgrounds are filled with hundreds of small animals, birds, and insects rendered with startling naturalism. Over 100 plant species have been identified, many of them shown with botanical accuracy. This attention to natural detail was not only decorative but also symbolic—each flower or animal could carry a meaning. Taken together, the tapestries are as much a celebration of the created world as they are of theological or romantic ideals.

Materials and Methods of Master Weavers

The primary materials used in the Unicorn Tapestries were wool and silk, dyed using natural pigments such as madder (for red), weld (for yellow), and woad (for blue). In some places, threads were wrapped in silver or gold to add brilliance, especially in the depiction of chains, jewelry, and noble garments. The tapestries’ vibrant colors have faded over the centuries, but even today, they remain striking in their visual power.

Weaving tapestries of this scale required a horizontal loom large enough to accommodate the entire width of the piece. The warp threads (running vertically) were set up first, and then the colored weft threads were passed over and under the warp to create the image. The weaver followed the cartoon drawing behind the loom, essentially working in reverse. Small metal rods, known as bobbins, were used to guide individual threads, allowing for precise color changes and detailed patterning.

A master weaver would oversee the process, coordinating the efforts of journeymen and apprentices. In many workshops, only the master had direct contact with the patron or designer. The others worked anonymously, preserving the collective tradition of the guild system. Although the tapestries bear no visible signature, the technical skill evident in every inch of the fabric is a testament to generations of accumulated knowledge and tradition.

The color palette of the tapestries is another marker of their artistry. The creators used subtle gradations in tone to create volume and depth, especially in the faces, clothing folds, and floral arrangements. This level of detail would not become common in European painting until the High Renaissance, making the tapestries a key transitional form between the Gothic and Renaissance visual worlds.

Millefleur and Detail in Nature

One of the most visually captivating features of the Unicorn Tapestries is the use of millefleur—French for “thousand flowers”—in the background. This style was particularly popular in late medieval and early Renaissance tapestry design, featuring a dense pattern of small, non-repeating flowers and plants scattered across the ground. Far from being random decoration, many of these plants were identifiable species with known symbolic meanings in Christian iconography and folklore.

Botanical analysis of the Unicorn Tapestries has identified more than 100 distinct species, including lilies, carnations, violets, daisies, and iris. The lily, often associated with purity and the Virgin Mary, appears near the unicorn in several panels. The iris, linked to the Passion of Christ, also makes a frequent appearance. Even humble plants like plantain and strawberry had medicinal or moral associations in the medieval worldview.

Animals and birds add to the richness of the scenes. Rabbits, dogs, deer, pheasants, and foxes appear in the background or hidden among the plants. Some serve symbolic purposes—such as the dog, traditionally representing loyalty—or function as reminders of the divine order in nature. The inclusion of these creatures reflects not only the artist’s observational skill but also a worldview in which every part of creation had meaning.

The naturalism of the millefleur backgrounds sets the Unicorn Tapestries apart from earlier, more stylized Gothic textiles. They reflect the growing interest in the observable world that would culminate in the Renaissance, even as they remain rooted in a thoroughly Christian symbolic system. The garden of the final panel becomes not just a backdrop but a spiritual space—one filled with the signs of both Eden and redemption.

The Role of the Unicorn in Medieval Culture

The unicorn held a unique place in medieval European thought. It was more than just a mythical beast—it stood at the crossroads of legend, theology, and moral instruction. Though no naturalist had ever seen a unicorn in the wild, bestiaries, sermons, and illuminated manuscripts described it as though it were real. The unicorn was believed to inhabit distant lands, difficult to reach and harder still to understand, reflecting the medieval mind’s preoccupation with the mystery of the divine and the limits of man’s knowledge.

By the 12th century, the unicorn had been fully absorbed into Christian theology through texts like the Physiologus, a Greek compendium of animal lore dating to the 2nd century AD. The unicorn was said to be strong, wild, and pure—a creature that could not be caught by ordinary means. Only a virgin could lure it to rest its head on her lap, making it tame and vulnerable. This image was quickly adopted by Christian writers as a symbol of Christ’s Incarnation, with the virgin representing Mary and the unicorn signifying divinity entering the world.

The unicorn also had roots in pre-Christian and classical sources. Ancient Greek and Roman authors, including Pliny the Elder and Ctesias, wrote of single-horned beasts dwelling in India or Ethiopia. These accounts were often exaggerated or misunderstood descriptions of animals like the rhinoceros or oryx, but they were believed for centuries. In medieval Europe, these texts were copied, embellished, and illustrated, giving rise to the enduring image of the unicorn as both historical and fantastical.

Culturally, the unicorn also came to represent a variety of noble virtues. Its white body stood for purity, its horn for strength and healing, and its aloofness for the difficulty of attaining spiritual perfection. For noble families, it became a popular heraldic symbol, often paired with the lion—representing both gentleness and courage. This duality, combined with its deep religious connotations, made the unicorn a perfect subject for aristocratic art, especially during the High Middle Ages and early Renaissance.

From Pagan Beast to Christian Icon

The evolution of the unicorn from classical myth to Christian symbol is one of the more fascinating cultural transformations in medieval thought. In ancient writings, the unicorn was often described in vague or contradictory terms. Ctesias, a Greek physician writing in the 5th century BC, described a wild donkey-like animal in India with a single horn, colored white, red, and black. Though likely inspired by second-hand tales of real animals, this account became a foundation for unicorn lore in Europe.

By the time of Saint Ambrose in the 4th century AD and Isidore of Seville in the 7th century, the unicorn had taken on new meaning. In their writings, it became a moral allegory—a beast that symbolized Christ’s humility and sacrifice. Its horn was said to neutralize poison, a metaphor for salvation, and its capture by a virgin stood for the purity of the Incarnation. These ideas were elaborated in sermons, stained glass, and manuscript illuminations, spreading the symbolism across all levels of European society.

Churches used the unicorn to teach moral lessons. The story of the unicorn and the maiden served as a vivid, accessible way to explain deep theological truths to congregations that may not have been literate. The unicorn’s capture became a parable for divine grace entering the world through the Virgin Mary. By the 12th and 13th centuries, it was not uncommon to find unicorns carved into cathedral capitals or painted onto chapel walls.

As the unicorn became thoroughly Christianized, it also retained some of its older associations with magic and mystery. The tension between the natural and supernatural, the real and the symbolic, only deepened its power as a cultural icon. In the world of the Unicorn Tapestries, this dual role—as both beast and symbol—is fully realized.

Virginity, Nobility, and the Hunt

The idea that the unicorn could only be tamed by a virgin was central to its role in medieval imagination. This detail appears in nearly every major bestiary and was widely accepted as a fact by medieval Europeans. The virgin’s ability to calm the unicorn was not just about innocence; it was about spiritual authority. Purity had real power, and the unicorn, like a soul in turmoil, was drawn to it.

This image carried strong implications for both religious devotion and courtly conduct. For Christian theologians, it reinforced the Church’s teachings on chastity and the sanctity of the Virgin Mary. For the nobility, it provided a moral framework within which romantic and sexual desire could be interpreted. The hunt for the unicorn became a metaphor for the pursuit of virtue—or the pursuit of a noble woman’s favor.

Hunting itself was a major part of aristocratic life in medieval Europe. It was both a pastime and a rite of passage, governed by strict codes and rituals. The unicorn hunt in the tapestries, while clearly fantastical, mirrors real hunting practices of the time—packs of dogs, horn calls, beaters driving game toward the hunters. This grounding in reality makes the symbolism all the more potent. The unicorn is not captured by strength alone; it must be approached with reverence, patience, and virtue.

The final panel, “The Unicorn in Captivity,” captures the essence of these ideas. The creature is chained but unharmed, enclosed but content. This could signify willing submission to divine love, the peace that comes after the soul’s struggles, or the fidelity of a lover who has finally pledged his loyalty. In all cases, it reflects a worldview where even mythical creatures were expected to embody timeless truths.

Theories and Debates: What Does It All Mean?

For centuries, scholars, theologians, and art historians have studied the Unicorn Tapestries in an effort to decipher their true meaning. Despite widespread admiration and extensive documentation, no single interpretation has been universally accepted. This ambiguity, rather than detracting from their significance, only deepens their mystery. The lack of surviving records—no contract, signature, or definitive provenance—has left modern viewers to rely solely on symbolism, visual clues, and comparison to similar works. In many ways, the tapestries operate like a riddle crafted in thread, inviting contemplation but offering few certainties.

Theories about the Unicorn Tapestries fall into several major categories. The most dominant view is theological: that the tapestries are an allegory for the life of Christ. Others believe the works were created to celebrate a marriage, using the unicorn as a symbol of romantic devotion, chastity, or even fertility. A third interpretation emphasizes dynastic power, suggesting the unicorn is a metaphor for a noble house that has triumphed over adversity, symbolized by the hunt. Still others see the works as a combination of all three perspectives, a multi-layered message encoded with both public and private meanings.

One reason the tapestries resist easy interpretation is that the panels themselves offer conflicting messages. The unicorn is hunted and killed, yet in the final scene it appears alive and tranquil. It defends itself violently in one panel and sits docilely in another. These contradictions may not be inconsistencies, but rather deliberate choices meant to convey paradoxical truths—such as death and resurrection, captivity and freedom, or purity and passion. In the world of medieval thought, paradox was not an obstacle to understanding—it was often the key to it.

Even modern science has entered the debate. Botanical analysis, textile dating, and heraldic research have all added pieces to the puzzle, but none have solved it. Instead, what we are left with is an artwork that defies reduction, drawing on sacred themes, noble ideals, and eternal truths without ever quite revealing its final purpose. It is this very quality that has ensured the Unicorn Tapestries’ survival not just as historical objects, but as living works of art that still speak across time.

Allegory vs. Literal Narrative

One of the longest-running debates surrounding the Unicorn Tapestries is whether they are meant to be interpreted as a literal story or as a symbolic allegory. At first glance, the panels appear to tell a straightforward tale: a hunt begins, the unicorn is chased, killed, and then appears alive again in a garden. This seems to follow a sequential narrative, much like a storybook or a visual sermon. The detailed realism of the setting and characters supports this reading, offering clear “chapters” in the unfolding drama.

However, many scholars argue that the story is not meant to be taken literally, but rather as a complex allegory. In this view, each panel conveys a distinct moral or spiritual truth, and the sequence is less important than the individual symbols. For instance, the unicorn’s capture by a virgin could symbolize the Incarnation, while its death and later revival could represent the Passion and Resurrection. The garden enclosure in the final scene might stand for paradise or marital fidelity, depending on the context.

Supporting the allegorical reading is the inclusion of countless symbolic elements—flowers, animals, gestures, and even clothing—that were well-known to medieval viewers as having deeper meanings. The use of heraldry also points toward a message meant for a specific audience, one that would have recognized certain family symbols and understood their connotations. In this sense, the tapestries function more like a sermon in silk than a story in pictures.

Yet, even among allegorical interpretations, opinions differ. Some focus on religious meaning, others on courtly love, and still others on political power. The richness of the tapestries lies in this very diversity of meaning, where the literal and the symbolic are woven together so seamlessly that one cannot easily be separated from the other.

Hidden Symbols and Scholarly Speculation

The Unicorn Tapestries are filled with visual motifs that have sparked decades of scholarly speculation. From the number of dogs in a scene to the plants blooming at the unicorn’s feet, each detail has been examined for hidden meanings. Some researchers have proposed that the tapestries contain esoteric or even mystical messages, drawn from Neoplatonic thought or medieval alchemy. While such theories are intriguing, most lack concrete evidence and remain speculative.

One interesting detail is the repeated use of the color white, especially in the unicorn’s coat and some of the hunting dogs. White traditionally symbolized purity, but in some contexts it also stood for martyrdom or spiritual perfection. The unicorn’s horn, always rendered in brilliant white or silver, was believed in medieval lore to have the power to purify poisoned water, a clear metaphor for Christ’s redemptive role.

The fountain shown in the second panel has also drawn attention. Fountains were a frequent image in medieval Christian art, often symbolizing baptism or the source of divine grace. The fact that the unicorn places its front hooves in the water could indicate its role as a spiritual cleanser or redeemer. Others have suggested that the flowing water is a reference to the sacraments, further reinforcing the Christological reading.

Another mystery is the presence of a specific pair of initials—AE—found in several of the tapestries. The identity of these initials remains unknown. Some have speculated that they refer to Antoine and Antoinette de La Rochefoucauld, potential patrons. Others suggest the initials might be a Latin motto or workshop mark. Like much about the tapestries, this detail invites questions more than it provides answers.

Bullet List: Top 5 Theories About the Meaning of the Unicorn Tapestries

- Christological Allegory – The unicorn represents Christ, and the hunt symbolizes the Passion, Crucifixion, and Resurrection.

- Courtly Love Narrative – The unicorn stands for a noble lover, subdued by a lady’s purity and love, as in chivalric romance.

- Marriage or Fertility Symbolism – The tapestries celebrate a noble wedding, with the unicorn representing loyalty and fruitful union.

- Dynastic Power Statement – The imagery reflects the triumph of a noble house, possibly La Rochefoucauld, through symbolic conquest.

- Esoteric or Mystical Allegory – The unicorn hunt encodes alchemical or Neoplatonic themes about the soul’s purification and unity.

From Castle to Museum: A Tumultuous Journey

While the Unicorn Tapestries now hang in peaceful splendor at The Met Cloisters in New York, their path through history has been anything but serene. Like many great works of medieval art, they were at one time nearly forgotten, stored away in the decaying halls of a French château. Their survival into the modern age is due to a fortunate mix of aristocratic stewardship, 19th-century rediscovery, and early 20th-century philanthropy. Each stage of this journey has contributed to their present-day mystique.

The tapestries were likely created in the Southern Netherlands around 1495–1505 AD and commissioned by a powerful French noble family, possibly the La Rochefoucaulds. By the 17th century, they were hanging in Château de Verteuil, a family estate located in western France. There, they remained for centuries, relatively undisturbed but slowly deteriorating due to poor storage conditions and exposure to the elements. By the 19th century, the tapestries had already suffered some fading, fraying, and water damage.

Their rediscovery came at a time when medieval art was enjoying a resurgence of interest, particularly among Romantic writers and collectors. In 1855, Prosper Mérimée, the French inspector of historical monuments (and author of Carmen), visited Château de Verteuil and recorded the tapestries’ presence. Other visitors soon followed, and the tapestries gained attention among antiquarians and art historians. Although some attempts were made to preserve or restore them, they remained in private hands and out of public view for decades.

By the early 20th century, the family had fallen on hard times, and the tapestries were placed on the market. Their rarity and beauty attracted international attention. In 1922, John D. Rockefeller Jr., the American industrialist and philanthropist, purchased six of the seven tapestries through the Paris art dealer J. J. Marquet de Vasselot. He acquired the seventh panel, The Unicorn in Captivity, separately, possibly from another branch of the family. His intention was not private ownership, but public preservation.

Discovery in a French Château

When the tapestries were discovered in Château de Verteuil, they were in a state of fragile neglect. The castle itself, dating back to the medieval period, had fallen into partial disrepair by the 1800s. The tapestries were reportedly being used as insulation—hung on walls more for their bulk than their beauty. Yet even in this humble setting, their rich colors and mythical imagery made an impression on visitors. Some sketches and descriptions from the period survive, showing how fascinated even amateur historians were with the mysterious unicorns.

The tapestries’ presence in the castle strongly supports the theory that the La Rochefoucauld family were the original owners. Their heraldic devices appear in several panels, and the family’s prominence in the French aristocracy makes them likely candidates for such a luxurious commission. It’s plausible that the tapestries were originally made to celebrate a marriage or dynastic event, then passed down through generations before being forgotten in an unused wing of the estate.

While some restoration was attempted in the late 19th century, it was limited and not always expertly done. Small patches were added to cover holes, and certain sections were reinforced with additional stitching. Despite these interventions, the original weaving and color palette remain largely intact—a remarkable fact considering their age and the conditions under which they were stored.

Their removal from the château and eventual sale was part of a broader trend during this era, as many European aristocratic families sold off heirlooms due to declining fortunes, inheritance taxes, and political upheaval. What was lost to France became a cultural treasure for the United States.

Arrival at The Met Cloisters

John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s acquisition of the Unicorn Tapestries was guided by a broader vision: the creation of a museum dedicated to the spiritual and artistic legacy of medieval Europe. That vision came to fruition in 1938 with the opening of The Cloisters, a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Built in the style of a medieval monastery and incorporating architectural fragments from five European cloisters, the museum was designed to offer visitors a contemplative experience rooted in Western tradition.

The Unicorn Tapestries were installed in a specially designed room, with controlled lighting and acoustics intended to evoke the solemn grandeur of a Gothic chapel. Their placement among other medieval treasures—altarpieces, sculpture, manuscripts—underscores their role not just as decorative art, but as spiritual narrative. At The Cloisters, the tapestries are displayed with space and reverence, allowing viewers to approach them slowly and absorb their symbolic depth.

Rockefeller’s decision to donate the tapestries rather than keep them in a private collection reflected his belief in cultural stewardship. He recognized that such works belonged to the public and to posterity, not just to the wealthy. His involvement also ensured that the tapestries were preserved using the most advanced conservation techniques available at the time, and that they would be protected against further decay.

Today, the Unicorn Tapestries remain one of the crown jewels of The Cloisters collection. They attract visitors from around the world and serve as an anchor for the museum’s mission to illuminate the art, architecture, and spirituality of medieval Christendom. Their presence in America—a land far from their origin—stands as a testament to the enduring value of cultural heritage and the responsibility to preserve it.

Pop Culture and Modern Fascination

Despite their medieval origins, the Unicorn Tapestries have captivated modern audiences far beyond the world of art historians and museum-goers. Their enduring visual appeal, layered symbolism, and sense of mystery have made them icons in popular culture. From animated films to fantasy novels, the tapestries have inspired countless adaptations, references, and reproductions. While many viewers may not know their full historical context, the images—especially The Unicorn in Captivity—resonate with a deep and nearly universal sense of wonder.

One of the most notable features of the Unicorn Tapestries is how they bridge the ancient and the modern. Their lush millefleur backgrounds and elegant, dreamlike composition make them seem almost surreal to modern eyes. As such, they’ve been repeatedly used to evoke otherworldliness, purity, or enchanted isolation. The image of the chained unicorn has become a visual shorthand for themes of longing, mystery, and redemption—making it an attractive motif for writers, directors, and designers working in visual media.

The rise of interest in medieval aesthetics during the 20th century—fueled by authors like J.R.R. Tolkien, fantasy illustrators, and medieval reenactment groups—brought the tapestries renewed attention. Their availability in high-quality reproductions, museum catalogs, and even home décor made them familiar to audiences who might never visit The Cloisters. Today, they are as likely to appear on a college dorm wall as they are in a serious art history textbook.

While their meanings remain complex and deeply rooted in the Christian and aristocratic worldview of the 15th century, the emotional core of the tapestries—beauty, loss, grace, and captivity—continues to resonate. In an age when much of modern culture seeks immediacy and spectacle, the quiet, enduring mystery of the Unicorn Tapestries offers a rare invitation to slow down, reflect, and wonder.

Appearances in Film and Literature

The Unicorn Tapestries have found a lasting place in literature and entertainment, especially works that explore fantasy, myth, or the intersection of innocence and power. One of the most famous examples is Peter S. Beagle’s 1968 novel The Last Unicorn, which includes direct allusions to the tapestries. Its 1982 animated film adaptation features visual references that echo the tapestries’ rich flora and the theme of a unicorn imprisoned yet noble.

They also appear prominently in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. In the films, the Gryffindor common room is decorated with tapestry reproductions, most notably The Unicorn in Captivity. This inclusion subtly reinforces themes of virtue, sacrifice, and magical innocence, aligning with the overarching narrative of the chosen one who endures trials and death before returning triumphant.

Even mainstream television has paid tribute. In the 1980s, the British series The Box of Delights used the tapestries to add atmosphere and medieval mystery to its time-traveling story. Their appearance in contemporary novels and fantasy series, particularly those inspired by Arthurian legend or medieval romance, shows their continued ability to inspire the imagination.

These uses are rarely exact replications, but they borrow heavily from the tapestry’s visual and symbolic vocabulary. The unicorn, once a creature of theological allegory, has become a flexible icon for everything from childhood wonder to moral courage—carrying forward the tapestries’ relevance in a secular and diverse cultural landscape.

Reproductions and Educational Uses

The tapestries’ popularity has led to a robust market for reproductions—some faithful, others purely decorative. Museums, universities, and private collectors have commissioned high-quality replicas for display, often woven using traditional techniques on Jacquard looms. While these reproductions cannot fully capture the subtlety of the original materials, they do preserve much of the visual power and scale of the originals.

In the academic world, the Unicorn Tapestries are frequently used to teach about medieval art, symbolism, and worldview. Their themes allow instructors to explore a range of topics: from feudalism and noble identity, to Christian theology, gender roles, and the nature of allegory. Art history courses often devote entire lectures to the series, using them as a case study in medieval visual literacy and narrative design.

Textbooks in both high schools and universities include the tapestries as part of broader discussions on European art before the Reformation. Their inclusion helps students grasp how image and meaning worked together in a time before widespread literacy. The tapestries’ ability to carry multiple layers of interpretation also makes them valuable for interdisciplinary studies in theology, literature, and cultural history.

Even churches and Christian schools have embraced the tapestries, using them in religious education to illustrate biblical symbolism. For younger audiences, simplified versions appear in coloring books and children’s literature, often focusing on the wonder of the unicorn rather than the deeper theological meanings. These uses keep the tapestries alive in cultural memory, even as their original context fades into history.

Conclusion: Faith, Fantasy, and the Fabric of Time

The Unicorn Tapestries are more than magnificent examples of medieval craftsmanship—they are a rare convergence of faith, fantasy, and artistic excellence. Woven over 500 years ago, they have survived war, neglect, and changing tastes, continuing to speak powerfully to modern viewers. Their allure lies not only in their beauty, but in their mystery. We do not know the name of the artist. We cannot say for certain who commissioned them or why. And yet, we are drawn to them—as people have been for centuries—not simply for answers, but for the invitation to reflect on the timeless truths they suggest.

At their heart, these tapestries communicate the struggle between wildness and taming, sacrifice and reward, mortality and eternity. Whether one sees the unicorn as a symbol of Christ, a noble spirit subdued by love, or a representation of personal virtue, the themes remain rooted in the Western moral imagination. They echo a worldview that saw order, beauty, and meaning in creation—and sought to reflect that in works of art. That is why they remain relevant in an age often marked by confusion, noise, and spiritual rootlessness.

In the modern world, saturated with mass media and fleeting trends, the Unicorn Tapestries offer something profoundly different: permanence. They are slow, silent, and deliberate—woven by hands that would never know their legacy. They represent a time when truth was believed to exist outside the individual, when stories were meant to teach, and when even mythical beasts served as symbols of eternal realities. This is not nostalgia. It is a recognition that some things—virtue, beauty, sacrifice—transcend their time and place.

To stand before the Unicorn Tapestries at The Cloisters is to glimpse a world that understood this. A world where the divine could be made visible in thread, where moral struggle could be embodied in a creature no one had ever seen, and where art was not simply for pleasure, but for truth. In a fractured age, these tapestries call us to remember, to wonder, and perhaps, to believe.

A Testament to the Western Imagination

The enduring power of the Unicorn Tapestries lies in their embodiment of Western ideals. They were made in an era when art was a form of worship, storytelling a moral enterprise, and beauty inseparable from truth. The tapestries are Western in their theology, their courtly elegance, and their celebration of human creativity. They affirm the importance of tradition, family, faith, and virtue—all values woven into their very fabric.

This makes them particularly relevant today. In a time when the legacy of Western civilization is often misunderstood or dismissed, the Unicorn Tapestries quietly proclaim its depth, discipline, and spiritual vision. They reflect a confidence in the moral order, in the hierarchy of being, and in the soul’s journey toward something greater than itself. That vision, though obscured in much of modern life, is still available to those who seek it.

These tapestries do not merely preserve history—they proclaim it. They speak of a world where even a mythical beast had a place in the moral cosmos, where art was crafted to endure, and where meaning was embedded into every thread. Their survival is a gift, and their message is still available to those who take the time to listen.

Why the Mystery Matters

It is tempting to seek a definitive explanation for the Unicorn Tapestries. Scholars continue to study them, looking for that final clue that will unlock their secrets. But perhaps the greatest value of these works is that they resist such easy conclusions. Their mystery is not a flaw but a feature—an invitation to contemplation rather than consumption.

Mystery has always played a role in faith, in art, and in love. It draws us in, not to confuse, but to deepen our understanding. In this sense, the tapestries reflect the deepest truths of the human condition. We are all hunting for something—for purpose, for belonging, for the divine. And like the unicorn, that which we seek may be found not by force, but by purity, patience, and grace.

Their mystery, then, is not a puzzle to be solved but a truth to be meditated upon. It challenges the modern tendency to reduce meaning to data or symbolism to literalism. The Unicorn Tapestries remind us that some truths are best understood not through explanation, but through beauty, silence, and time.

Key Takeaways

- The Unicorn Tapestries are a set of seven late 15th-century artworks blending myth, Christian allegory, and courtly symbolism.

- They were likely woven in Flanders and commissioned by a noble French family, possibly the La Rochefoucaulds.

- The unicorn symbol carries deep theological meaning, especially relating to purity, the Virgin Mary, and Christ’s Passion.

- The tapestries were rediscovered in the 19th century at Château de Verteuil and later brought to The Met Cloisters in New York.

- Their timeless beauty, intricate detail, and unresolved mystery continue to captivate scholars and modern audiences alike.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Where are the Unicorn Tapestries today?

They are housed at The Met Cloisters, part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. - When were the Unicorn Tapestries made?

They were woven between approximately 1495 and 1505 AD in the Southern Netherlands. - Who commissioned the tapestries?

While not definitively known, they are believed to have been commissioned by the La Rochefoucauld family. - What is the meaning of the unicorn in the tapestries?

The unicorn has been interpreted as a symbol of Christ, romantic love, purity, and noble virtue, depending on the context. - Are the tapestries religious or secular?

They blend religious and secular themes, allowing for interpretations grounded in Christian allegory, courtly love, or dynastic pride.